|

MESA VERDE

A Prehistoric Mesa Verde Pueblo And Its People |

|

A Prehistoric Mesa Verde Pueblo And Its People

By

J. Walter Fewkes

1916

an excerpt from Annual Report,

Smithsonian Institution

A PREHISTORIC MESA VERDE PUEBLO AND ITS PEOPLE.

By J. WALTER FEWKES.

[With 15 plates.]

INTRODUCTION.

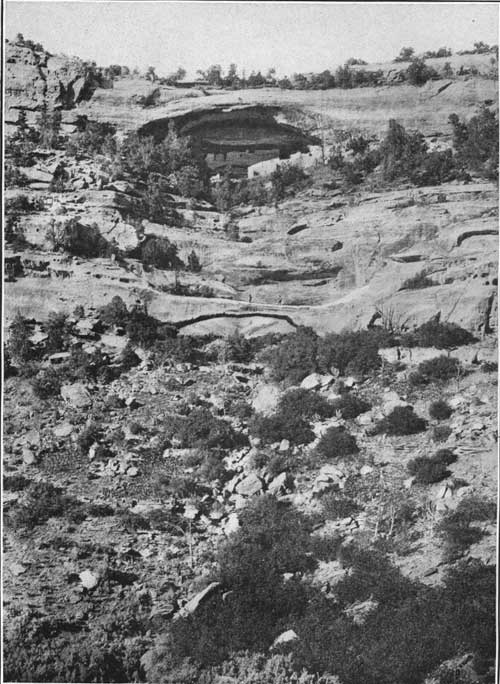

The Mesa Verde, or Green Plateau, is situated in the southwestern corner of Colorado and was set apart by Congress from the Ute Reservation for protection of its prehistoric remains. Its form is oval, measuring about 42,000 acres, with an average elevation of over 7,000 feet above sea level, rising abruptly on the north side to 8,700 feet, over 1,500 feet above the plain. Its surface is cleft by deep, almost parallel canyons opening into the Mancos Valley on the south, between which are spurs of the mesa sloping gradually southward. In the canyons (pl. 2) are located the most remarkable cliff dwellings of the Southwest. The top of the plateau is dotted with mounds of earth and stone. The present article deals with one of these mounds, which was excavated and the exposed ruins repaired by the Smithsonian Institution, during the months of July, August, and September, 1916, at the request of the Secretary of the Interior, following a recommendation of the writer in his report to the latter on field work at Sun Temple in the summer of 1915.

Clusters of mounds composed of artificially worked stones and earth situated on the surface of the mesa have long been known, and from indications these piles of stones were believed to mark the sites of buildings. None of these mounds, however, had been opened, or their contents investigated. The plan of operations was to determine, by excavations, the character of the buildings concealed in them, and to interpret their cultural relations and significance. A cluster of mounds known as the Mummy Lake group was chosen as promising and advantageously situated for this purpose. The excavation of one mound of this cluster revealed a large building of a type new to the plateau.

The importance of the results of the work and their bearing on southwestern archeology may be better appreciated after reading what immediately follows. A portion of the area now known as Arizona, Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico was inhabited in prehistoric times by Indians culturally unlike those of any other region of North America, and for that reason this unique territory bears the name Pueblo culture area. It is, in fact, the only aboriginal culture area where buildings have determined the name, being distinguished from all others mainly by architectural characters. This limitation of characteristic terraced communal houses to a geographical area leads us to associate climate or other conditions of that area with peculiarities of buildings, as cause and effect.

Of man when he first entered the Southwest, we know little save that his physical features show that he was an Indian. The time of his advent is in doubt. Considerable obscurity also exists regarding the direction whence Indian colonists entered this district, but there is no doubt regarding the geographical locality where Pueblo culture, judged from the character of buildings, originated. The immigrant clans that first peopled the Southwest are supposed to have come from people who built neither cliff dwellings nor pueblos, consequently this style of dwelling originated exactly where it is now found.

But the Pueblo culture must not be interpreted solely by peculiarities in buildings, for although it receives its name from architectural characters, there are influential factors that it shares with those of other tribes of Indians which are very important. One of the most noteworthy of these is the possession of maize or Indian corn as a reliable food resource. Agriculture is one of the cornerstones of the Pueblo culture, as masonry is another. When man first entered the Southwest he knew little of the advantages of stone as a building material, for he built his hut of mud, sticks, or possibly of skins of animals. The North American Indian became a good stone mason as a result of a life in caves. Nowhere outside of the Southwest were elaborate buildings1 constructed of dressed stone by the aborigines north of Mexico. Masonry and agriculture, then, are the primary factors that determined the essential peculiarities of Pueblo culture.

1Stone walls and vaults were, of course, constructed elsewhere by Indians; cf. Mr. Gerard Fowke's article, Bur. Amer. Ethnol. Bull. No. 37, et al.

The Mesa Verde was set aside as a national park on account of its prehistoric stone buildings and monuments. While it presents rare facilities for a study of aboriginal architecture, it shares with other regions of the Southwest the condition that imperishable aboriginal buildings have survived from prehistoric times. Evolution of masonry in this region is a development which occurred in prehistoric times, or before the advent of the white man. No European ever saw an inhabited cliff dwelling on the Mesa Verde, and no article of European manufacture has ever been found in the undisturbed débris of the rooms. These cliff dwellings were abandoned before the Spanish conquest.

The inhabitants of the caves on the Mesa Verde were ignorant of hieroglyphs or letters, and therefore have left no written account of their origin and early history, although vague traditions are preserved by their descendants, especially among living Pueblos, as the Hopi. The most reliable data we now have to aid us in interpreting their culture are their buildings and archeological remains, or monuments, and minor antiquities, called artifacts, especially objects of burnt clay, that they have left behind. Their houses are the most significant.1 As pointed out by Westropp, in referring to prehistoric and historic cultures of other races: "Architecture is the external form of their public life; it is an index of their state of knowledge and social progress."

1Probably some writers on classical archeology would hardly consider cliff dwellings architectural forms.

One type of building characteristic of this culture is illustrated by Spruce-tree House and Cliff Palace, but this is not the only form. There are others, such as Sun Temple, brought to light in the summer of 1915, in which we find a building specialized for religious purposes.

Field work in the Mesa Verde during the summer of 1916 first revealed still another type differing considerably from the two preceding. This type, locally new, is known to ethnologists as a pueblo, commonly defined as a terraced community building constructed in the open or not attached to cliffs. It is a representative of many buried houses on Mesa Verde, and it is not too much to say that formerly there were as many buildings of pueblo type on top of the plateau as there were cliff dwellings in its canyons. Manifestly a knowledge of the Mesa Verde variety of pueblo is desirable, and a description of it will enlarge our conception of prehistoric culture in this locality. The object of the present article, then, is to make this known as a contribution to our knowledge of the aborigines of Mesa Verde.

The general condition and situation of mounds on the surface of the plateau will first be considered.

THE MUMMY LAKE GROUP OF MOUNDS.

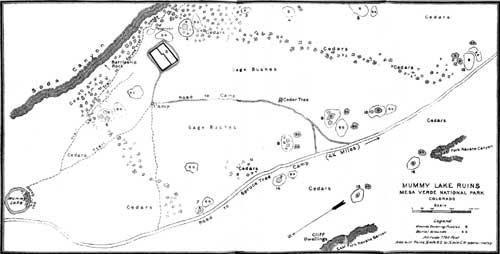

One of the best known group of mounds in the Mesa Verde National Park is situated south of a reservoir called Mummy Lake. There is no good reason for calling this prehistoric reservoir a lake, for it is not a lake, and no mummies have ever been found in or near it. The term "Moki Lake," by which it is sometimes designated, is equally meaningless, but both names are so firmly fixed in literature that it is difficult now to substitute others.

The best description of this reservoir is the following, quoted from Baron Nordenskiöld's "Cliff dwellers of the Mesa Verde" (p. 74):

A structure of considerable size, which was probably utilized for purposes of irrigation, lies on Chapin Mesa, some kilometers above the great ruins and not very far from the slope into Montezuma Valley. A large depression 30 meters in diameter is surrounded by a low, circular wall 4.5 meters thick. Water was probably conducted to this reservoir from some neighboring gulch. Traces of a ditch which formed the connection have been observed north of the reservoir by Richard Wetherill. A view of the reservoir is given in figure 43, which, however, shows only a part of a low, ring-shaped mound overgrown with bushes, all that is left of the thick wall. Quite near the reservoir we find the ruins of a considerable village, but the walls are now leveled with the ground, leaving only huge heaps of stone to mark the site.

Mummy Lake, or Moki Lake (pl. 7, fig. 1), is an artificial depression surrounded by an oval or circular ridge of earth, in places outlined by double walls of stones suggesting rooms. Excavations at the base of these stones, however, show that their foundations do not extend far below the surface; but work thus far has not been sufficient to prove conclusively that there were not rooms on the periphery. Mummy Lake lies on the northern edge of a group of mounds where the slope of the surface of the plateau would seem to indicate that water could be readily drawn from it. It is probable that the farms of the ancients were situated between the pueblos of the Mummy Lake group, and that these farms were irrigated by water drawn from this reservoir by means of irrigating ditches. In the time that has elapsed since the Mummy Lake pueblos were deserted the reservoir, like the ditches, has been filled with wind-blown sand or soil, so that its depth has greatly diminished, and at present water remains in it only a short time. Probably in prehistoric days it contained a perpetual water supply of a purer quality than now, when it is fouled by cattle excrement and made impure by mud washed into it from the surrounding banks; and if such were the case the reservoir probably supplied the neighboring pueblos with drinking water, since springs in this neighborhood are remote and very difficult of access. For instance, at the bottom of Soda Canyon there is an unpalatable soda spring, a climb from which to the pueblo is very arduous. Another spring, at the head of the same canyon, now used for watering stock, is over a mile distant, while a third possible source of palatable water is near the head of Navaho Canyon, even farther away. There was a small reservoir, possibly communicating with the larger by canals, now clogged with sand at each mound in the group. One of these minor reservoirs is indicated on the map near the mound excavated.

PLATE 1. DISTRIBUTION OF MOUNDS IN MUMMY LAKE GROUP. SURVEYED BY C. STANSBURY. )(click on image for a PDF version) |

A much worn trail extended from Mummy Lake to Spruce-tree House, just east of the house excavated, and between it and the rim of Soda Canyon. This trail, used by horsemen before the Government road was constructed, was probably an old Indian path of great antiquity, connecting the various pueblos of the Mummy Lake group with Spruce-tree House and Cliff Palace. A steep branch trail descends from it over the rim of Soda Canyon to the spring above mentioned, near which are mounds of ruins sheltered by Steamboat Rock. This trail may have been used by water carriers in prehistoric times.

The position of the mounds on the plateau near Mummy Lake were first designated on an excellent map of Mesa Verde, published by the United States Geological Survey. It is evident from this map that the cluster of mounds near Mummy Lake is only one of several groups; for instance, from the rim of Soda Canyon, looking north and east, four similar clearings can be seen, in each of which are several artificial mounds, all of which have the same general form and are covered with sagebrush.1 No regularity is noted in their arrangement (pl. 1), but they vary in size and shape, all appearing to have, as a common feature, a central depression, which, judging from that excavated, indicates a large kiva. We find superficial evidences of rectangular and oval houses, and in one instance the building under the mound may have a D shape. Fragments of walls projecting above the ground are absent in all cases, but in one or two instances the direction of the buried wall can be followed for a few feet by surface indications.

1This relation of mounds to sagebrush covered clearings is discussed by Dr. Prudden, Amer. Anthr., Vol. 16, No. 1, 1914.

As these communes or clusters of small pueblos are more conspicuous in clearings than among the thick cedars, the question naturally arises whether they were built before the cedars grew or whether man burnt or otherwise removed the trees of the forest before he laid their foundations. The author inclines to the belief that the clearings were made by the hand of man, and that cedars were growing on the mesa when man appropriated it for his habitation or for planting. When once removed the constant tramping of people would certainly prevent trees from again growing on the cleared areas. At the time the buildings were inhabited they were surrounded by farms cleared of underbrush, and it appears from the amount of sand and soil filling the rooms of the pueblo that the wind played a great role in transporting sand to the mound from the surface of the bare earth. Sagebrush or trees would tend to anchor the soil and prevent its blowing away, which implies that the sagebrush has grown since the fields were no longer cultivated. As shown on the map (pl. 1), one or two of the smaller mounds of the group lie outside the clearing or in the cedars, a few of which trees also appear on top of the mounds. It may be mentioned that there is no evidence of a sagebrush clearing in the area about Sun Temple, which supports the theory that it was unfinished and uninhabited. Had Sun Temple been a domicile we would expect what we find in the neighborhood of Mummy Lake, some evidences of cultivated fields.

The sagebrush clearings are very fertile and throughout the summer months are carpeted with flowers, the most abundant of which is the "Indian paint brush"; later these plants, rare or unknown among the cedars, are succeeded by various species of asters. On account of the large number of flowering plants in the sagebrush clearings, unusually tame humming birds are very common, but with the advent of autumn they likewise vanish and the leaves of the scrub oaks change their colors and the mesa top is brilliantly painted with bright yellow and red. Almost everywhere, especially over the surface of the mounds, fragments of pottery are abundant, and here and there on the level surface between the mounds are remains of low stone walls, suggesting pit-houses,1 gardens, or irrigating ditches.

1It would be futile in the present state of our knowledge to speculate on the number of the inhabitants of these buildings long ago fallen into ruins, if simultaneously inhabited. There is no doubt it was large, much greater than suspected by early investigators. We are on the threshold of a great research and every year's field work will advance us a step in deciphering the history of this interesting race.

There are several clusters of mounds visible from near the Mummy Lake group. On the side of Soda Canyon there is an elevated outcrop, called Steamboat Rock, which protects a cluster of mounds, with sunny southern exposure, from the north winds. In a clearing on hills near the head of Soda Canyon there are also mounds or sites of former pueblos. It is important to note that these groups of mounds always occur in sagebrush clearings; their occurrence among cedars, where they are smaller, is common but less conspicuous. The many flowers blooming in these localities show that the land is rich, and it is probable that Indian corn could still be grown on the Mesa without artificial irrigation.

PLATE 2. TYPICAL MESA VERDE CANYON, LOOKING SOUTH. |

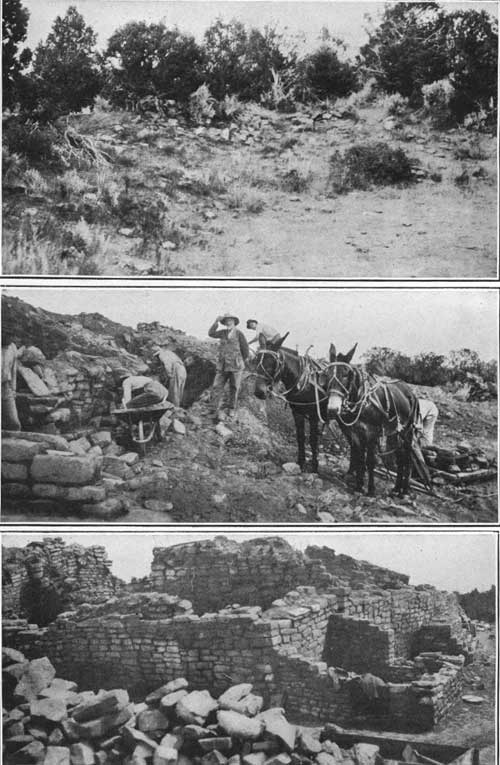

MOUND EXCAVATED.

The mound in the Mummy Lake group chosen as a type for excavation to determine the character of Mesa Verde pueblos is situated four miles and a quarter due north of Spruce-tree House, and is one of sixteen scattered at intervals on both sides of the Government road. It stands about an eighth of a mile east of this road, a few steps from the rim of Soda Canyon. This pueblo (pl. 4) might be called Far View House, for the distant southern outlook from it is very fine and has been commented upon by almost every visitor.2 From its highest rooms the corners of the four States of Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado—the only case in the country where four States meet in one point—can be seen far to the southwest. Sleeping Ute Mountain, Ship Rock, once called the Needles, and distant mountains of Arizona, rise on the horizon to the south and west. In the less distant foreground, beyond a forest of cedars, one can trace several important canyons of the Mesa Verde, among which may be mentioned Navaho, Mancos, and Soda. When the wind is favorable, the flag at Spruce-tree camp can be seen as a speck waving above the trees; the course of Spruce-tree Canyon can be traced without difficulty through its whole length. The surface of the land south of the ruins is covered with a dense forest of cedars and pin˜on trees sloping to the south. Looking back from the well-known tower at the head of Navaho Canyon or across country from the fine ruin, Spring House, one could make out the workmen on the ruin, with a good glass. Not many feet (80) from the southwest corner of the court there is in view a large mound pleading for excavation which may have an interesting story to impart regarding aboriginal culture. Two mounds in the group are situated in the cedars beyond, and a third, of large size, lies just south of the edge of the sagebrush clearing. The site of the pueblo is the most prominent one in the southeast corner of the area, and in a way this pueblo may be said to dominate the others. It was probably the largest, the most populous and important.

2The name Far View House, which calls attention to this fact, was suggested by one of my workmen, Mr. Jason Myers.

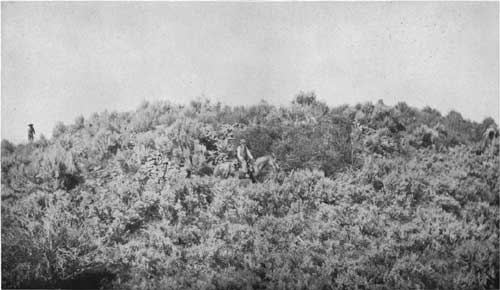

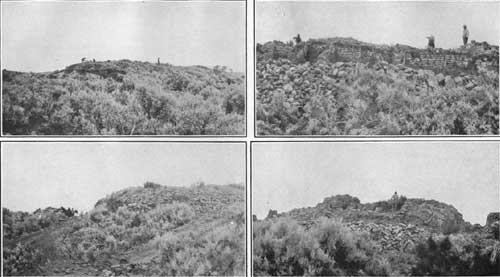

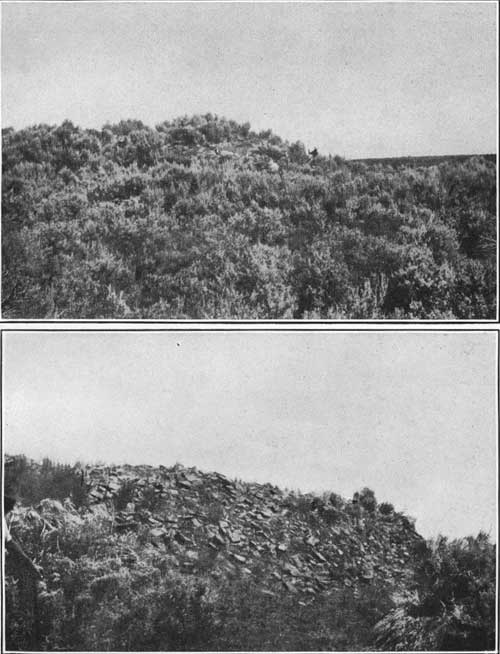

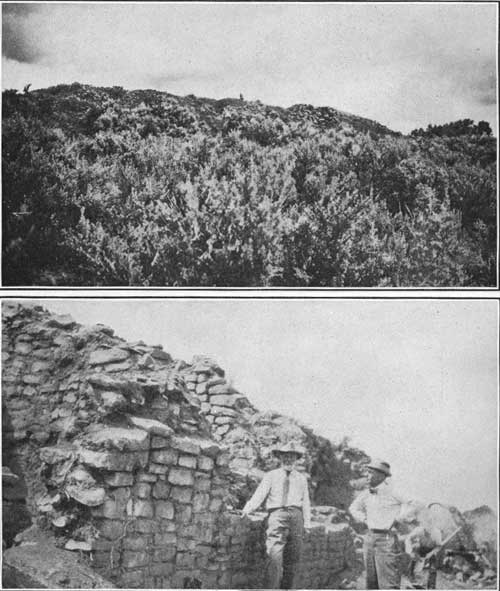

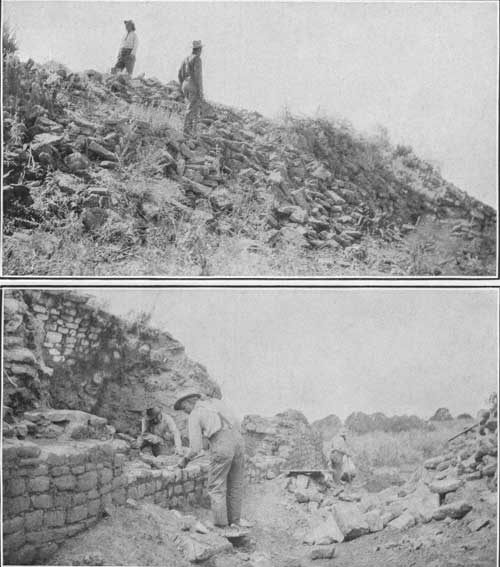

When excavation work was begun, the entire surface of this mound, like all of the group, was covered with sagebrush (pl. 3) and, like them all, showed a deep circular depression in the interior strewn with stones and débris. Some seeker after curiosities had dug a shallow trench on the highest point of the north side, revealing a fragment of a well-made wall and the sides of a doorway. From this a trench had been dug across the mound to what was eventually found to be the south side. This excavation had not determined the form, size, or height of the building, and probably did not reward the workmen with the small objects they sought.

PLATE 3. FAR VIEW MOUND SOUTH SIDE BEFORE EXCAVATION. PHOTOGRAPH BY FRED JEEP. |

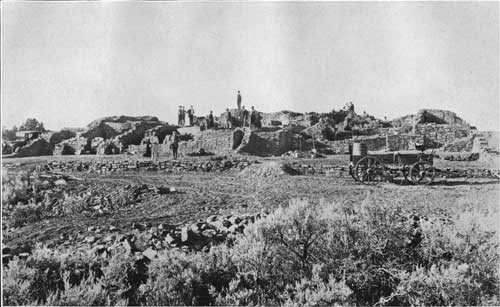

PLATE 4. SOUTH SIDE OF FAR VIEW HOUSE AFTER EXCAVATION. PHOTOGRAPH BY GEORGE L. BEAM. |

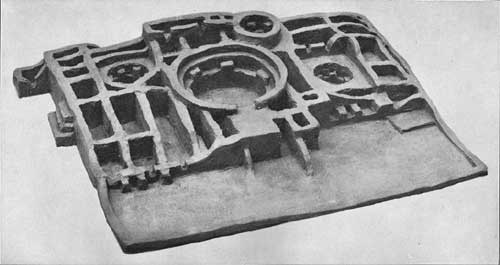

PLATE 5. MODEL OF FAR VIEW HOUSE. (FOR DETAILS CONSULT FIG. 1.) |

Almost every visitor to the pueblo while the excavation was in progress remarked on the quantity of débris that filled the rooms and naturally asked whence it came. Many visitors were sure it indicated a great age; that a long time had elapsed to fill the rooms. The writer has also given much thought to this condition and concludes that this alone does not prove a great antiquity. It is difficult to explain this condition and to draw conclusions therefrom, but an examination of the arrangement or stratification of débris in the rooms is significant. For several feet below the surface the débris consists mainly of fallen stones mixed with adobe, resulting from the overturned tops of the walls. Penetrating deeper or below this stratum, soil free from stones was found. This material, identical with the sand of the plateau, appears to have been blown into the rooms or brought from the surrounding fields by wind storms. The accumulation of débris due to falling walls and the addition of wind-blown sand would progress very rapidly as long as the wall projected above the ground, but would then cease. That time might be measured by centuries, certainly not by millenniums. Lower still occurs a layer of ashes with fragments of charcoal, a "pay dirt" in which artifacts are common. This is mixed with adobe, evidently remnants of plastering. Deeper sometimes follows another layer of sand or an aeolian deposit; a sequence not uniform and not the same in thickness in all rooms. Evidently some of the rooms had been deserted and the sand accumulated to a depth of 2 or 3 feet, after which they were reoccupied and foundations laid on the sand, the new walls having been constructed to the height of the adjoining walls on this foundation.

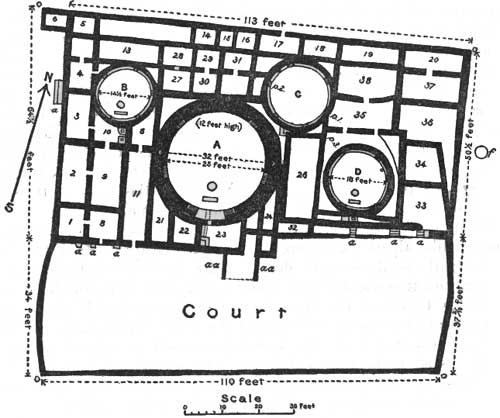

FIG. 1.—Ground plan of Far View House. Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado. |

GROUND PLAN OF BUILDING.

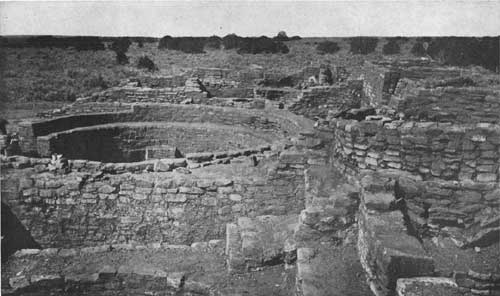

The arrangement of rooms reduced to a ground plan is seen on figure 1. The lowest story of the main building has 40 secular rooms and four ceremonial chambers or circular kivas. A few of the secular rooms have not been excavated to their floors. The majority of these are arranged in two tiers on the north and west sides. They are two-storied; the floor beams of the second story, which are rafters of the first, were found and left in place. The row of rooms north of kiva A likewise show evidences of the existence of a third story, so that it may be said there were about 50 secular rooms in the building.

All the secular rooms on the west side were completely excavated, and earth was removed from all kivas. The court or dance plaza is situated south of the main structure and is inclosed by a low wall measuring 110 feet on the south side, 37-1/2 feet on the east and 34 feet on the west side.

The peculiarity of this pueblo consists of a large central circular kiva, around which are grouped secular rooms, to which are added smaller circular kivas. This central room recalls a tower, but, unlike some of the towers, this and the smaller kivas have pilasters attached to the walls for support of a vaulted roof. The great size of the central kiva suggests that the room was not limited to one clan; it points rather to a fusion of clans forming so intimate a union of several families that the room may no longer be considered as limited to men of one clan, but the meeting place of a fraternity of priests, drawn from several clans. The formation of such a fraternity is an advance, sociologically speaking, upon what we find indicated by the small clan kivas of cliff dwellings and implies, more recent construction.

The regularity of the secular rooms, as shown in plate 5, strikes the observer at first sight. The partitions separating these rooms run north-south and east-west and are continuous through the pueblo. No such regularity is found in cliff dwellings, although it is a marked feature of pueblo ruins along the Chaco and elsewhere. Inhabited pueblos as Zuñi, Walpi, and others show this character only to a limited extent.

The rooms of this pueblo are consolidated into a rectangular form with straight walls broken on the south. The building is oriented approximately to the cardinal points, and terraced to secure, sunny exposure on the south side. The method adopted by the Mesa Verde people in orienting their buildings, as Sun Temple, seems to have been followed at this pueblo, and reveals a knowledge of solstitial sun rising which is instructive. The sun priests of the pueblos had, of course, no compass and probably the polar north was unknown to them. Their north, west, south, and east, as with the Hopi, are not the same as ours and the line of the south wall of Sun Temple was determined by the position of the sun. It was not made haphazard, but was carefully thought out and determined by astronomical observation before the foundation was laid down. At the autumnal equinox theoretically the sun rises in the east and sets in the west. In other words, sighting from the shrine along the so-called south wall on that date we ought to see the sun rise on a continuation of that line, if the wall extended exactly east and west. Observation shows that such is not the fact; the south wall does not extend exactly east and west. On the morning of the 21st of September, in company with several others, the writer determined this by observation; and found the line of the south wall if extended would touch the point of sunrise on the horizon a little more than 20° north of the extended line of the so-called south wall.

The same is true at sunset as viewed in the opposite direction as observed by my friend, Mr. T. G. Lemmon. The sun on that date sets about 20° from the extended line of the so-called south wall, which, if projected, would touch the point of sunrise at the summer solstice. This is so exact that the builders of Sun Temple probably determined the direction of the wall by observation of the sun as seen from the sun shrine at that solstice. The point of summer solstitial rising of the sun, as observed on the horizon, as well as sunset in mid-winter were cardinal points among them, as among the Hopi, and determined the lines of their temple devoted to sun worship. It seems to have been in somewhat the same way that the orientation of the pueblo at Mummy Lake was determined, but as the south wall is more irregular and the building more patched upon this side, it was not as easy to make observations there as at Sun Temple, but it was possible to use the north wall for that purpose.

Inasmuch as some of the highest walls had been reduced in altitude by the fall of their tops there had accumulated around their foundations a mass of detached fragments. The remains of fallen walls were especially extensive along the north wall, and the removal of this material was a work of considerable magnitude. Scrapers and stone boats were used for that purpose but the wall itself was laid bare by hand. The funds appropriated for this work were insufficient to permit the removal of this mass to a considerable distance to make the desired grading, but an automobile road was constructed around the ruin so that it can be visited with little inconvenience.

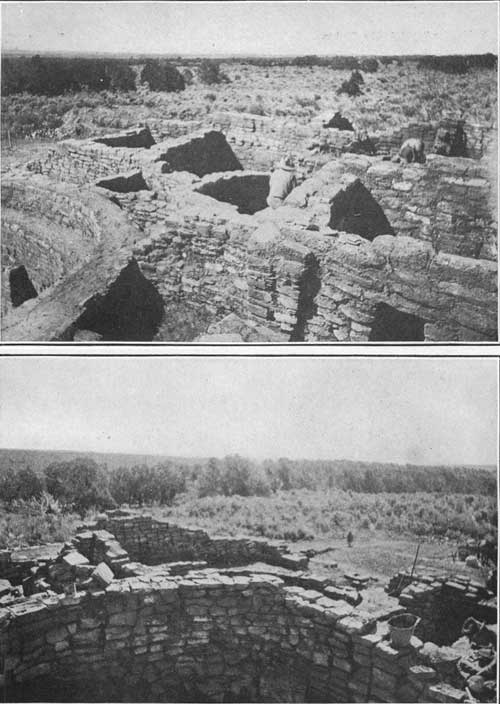

The excavation was begun on the northwestern corner of the mound (pl. 6), which later proved to be a small square room (pl. 6, fig. 3) annexed to this angle of the building. It was found that the greater part of the northern wall had been reduced to about 6 feet in height, and that the partition walls of several rooms formerly attached to it had been shattered. The east wall (pl. 6, fig. 4) was in somewhat better condition, but inclined so much outward that it was considered advisable to construct a buttress to hold it up. The south wall (pl. 8, figs. 1, 2) was irregular and much broken down; here (fig. 1, a, a, a,) buttresses were necessary. Near a recess situated midway in the length of the wall props (aa, aa) had been constructed by the aborigines to hold it from falling while the building was still occupied. The east wall also leaned considerably and had to be repaired. There is fine masonry in certain portions of all these walls (pl. 9, fig. 2; pl. 10, fig. 2), but on the whole it was inferior to that seen at Sun Temple.

PLATE 6. 1 (top left). NORTH WALL, FIRST STAGE OF EXCAVATION. PHOTOGRAPH BY E. A. WEIL. 3 (bottom left). NORTH WALL, SECOND STAGE OF EXCAVATION. PHOTOGRAPH BY E. A. WEIL. 3 (top right). NORTH WALL, COMPLETELY EXCAVATED. PHOTOGRAPH BY E. A. WEIL. 4 (bottom right). EAST WALL, AT NORTH END. PHOTOGRAPH BY E. A. WEIL. |

PLATE 7. 1 (top). MUMMY LAKE, LOOKING EAST. PHOTOGRAPH BY MRS. C. R. MILLER. 2 (middle). WESTERN END OF SOUTH WALL, PARTIALLY UNCOVERED. PHOTOGRAPH BY MRS. F. W. CHINKSCALES. 3 (bottom). NORTHWEST ANGLE, COMPLETELY EXCAVATED. PHOTOGRAPH BY J. WIRSULA. |

PLATE 8. 1 (top). SOUTHEAST ANGLE OF MOUND BEFORE EXCAVATION. PHOTOGRAPH BY FEWKES. 2 (bottom). SOUTHEAST END BEFORE EXCAVATION. PHOTOGRAPH BY FEWKES. |

PLATE 9. 1 (top). MOUND FROM SOUTHWEST BEFORE EXCAVATION. PHOTOGRAPH BY J. WIRSULA. 2 (bottom). MASONRY OF NORTH WALL. PHOTOGRAPH BY MRS. F. W. CHINKSCALES. |

As the number of rooms is greater than in Sun Temple, the work of excavation was more laborious than in the preceding summer, the shattered walls necessitating more repair work. The walls of a few rooms had been constructed on sand foundations, indicating that these rooms had been deserted and reoccupied. Other walls showed evidences of having been repaired while rooms were still occupied. The writer had no doubt that the building was a habitation, as many objects of household use were found at all depths from the very inception of the work.

The main north wall, exclusive of a small room of unknown use on the northwest angle, measures 113 feet from the northeast to the northwest corner, and was formerly about 20 feet high. The east wall extends 50-1/2 feet and the west wall 64-1/2 feet, both averaging about 10 feet high. There is a court surrounded by remnants of a wall rising a foot out of the ground on the south side. This wall rises highest where it joins the southeast and southwest angles of the main building. About midway in its length there is a recess in the south wall, evidently intended to hide the entrance ladder, resembling a similar recess at Sun Temple and Cliff Palace. The angles of this recess and the accompanying wall show good masonry; the corners inclined slightly outward, not being properly bonded to the remaining wall. The masonry throughout is fair but shows all the faults of cliff dwellers' work; joints unbroken, corners not bonded or properly tied to the other walls. The adjoining surfaces of the superposed stones were not flat, the mason relying upon slivers of stones, set in mud, to fill the intervals between them. He so multiplied the number of these stones that it weakened the walls, for the mud in which these were inserted easily washed out and the walls became unstable in course of time, notwithstanding they are thick, though in some cases the walls are narrow, not more than a few inches wide. Marks of human hands, and in a few instances impressions of corncobs were seen in the pointing of the walls—the latter perhaps accidental; no marks of a trowel were found.

Large, flat, thin, unworked stones set on edge occur at the southwest inner corner, where the wall surrounding the court joins the south wall of the main building. These stones are of such a size that they may be called megaliths, as it would require three men to handle one of them. Their insertion in the wall is regarded as a survival of a stage in southwestern masonry antecedent to the employment of hewn stones.1 As a rule there were no stones in the wall construction that could not be carried by a single pair of hands.

1Jackson describes an extensive wall of a ruin in Montezuma Canyon constructed in this manner.

A majority of stones show evidences of artificial pecking or dressing on their surfaces, a few being smoothed by attrition. Plastering as a rule is absent, but appears in layers over the surfaces of the small kivas. Its absence on the rectangular rooms and presence on the kiva walls suggests that it was protected by the vaulted roofs of the latter, which fell long after those of the former.

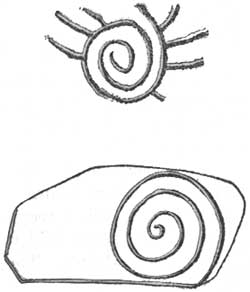

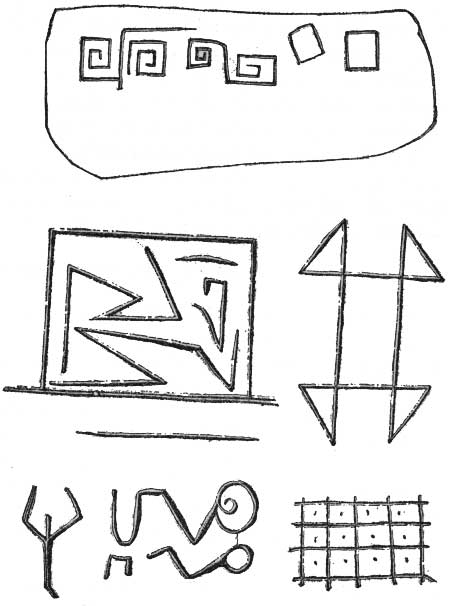

There are many stones with incised decorative figures, possibly "mason marks," different from those of Sun Temple set in the inner walls of the building. The spiral (fig. 2), representing the serpent of the water, occurs several times. The same figure was noticed on a round room lately discovered a mile from Spruce-tree House and on a round tower in Cannon Ball ruin, near the McElmo. One of these spirals was accompanied by radiating, peripheral, parallel lines, suggesting a figure of the feathered snake. Several of the more striking figures from stones fallen or still remaining in the walls are shown in the accompanying figures (fig. 3). They resemble designs on black and white pottery ware.

FIG. 2.—Serpent symbols incised on rocks in masonry. |

FIG. 3.—Incised figures on masonry. |

Various interpretations have been suggested to explain these figures, some of which are fanciful; there is no reason to doubt that they were primarily decorative, but they may also be symbolic. The complicated form of several incised figures suggests something more than meaningless efforts at embellishment, but it is too much to hope that they have any value as inscriptions. Although these designs are regarded as decorative, the limitation of the spiral to round rooms, towers, or kivas hints at a deeper significance. There is an obscure legend among the Hopi that circular kivas are connected in some way with snake ceremonials, and the association of the spiral sign and circular rooms seems to support, in a way, this idea.

TYPES OF ROOMS.

The rooms have two shapes, circular and rectangular, with triangular recesses between them, which are inclosures, not rooms. The circular rooms are evidently kivas or ceremonial chambers, evolutions of the men's rooms of an early time. The four circular kivas are identical in form and architectural features with similar rooms in cliff houses, which identity may be explained by the fact that religious buildings preserve archaic forms. They are, as a rule, better constructed than secular dwellings. The secular rooms have a general likeness in form, size, and vary considerably, but position of doorways.

PLATE 10. 1 (top). SOUTHWEST ANGLE OF MOUND BEFORE EXCAVATION. PHOTOGRAPH BY FRED JEEP. 2 (bottom). NORTH WALL, LOOKING WEST. PHOTOGRAPH BY FRED JEEP. |

PLATE 11. 1 (top). SOUTHWEST ANGLE, PARTIALLY EXCAVATED. PHOTOGRAPH BY J. WIRSULA. 2 (bottom). SOUTHWEST ANGLE, PARTIALLY EXCAVATED. PHOTOGRAPH BY J. WIRSULA. |

The majority of rooms found in Mesa Verde cliff houses fall into the following types:

1. Ceremonial rooms or kivas: These are circular,1 sometimes D-shaped, generally subterranean. There are two varieties of kivas—those that formerly had a vaulted roof and those with a flat roof. Banquettes and pilasters, fire holes, ventilators, and deflectors are present in the former.

1There is said to be a rectangular kiva in one of the undescribed cliff dwellings of the park.

2. Storage rooms: These are generally situated on the ground floor or below the others. They are without windows and were apparently entered from the roof; but often with side entrances communicating one with another. The largest number of rooms in cliff house are for storage of corn and other possessions. This type may be regarded as one of the oldest.

3. Sleeping rooms: This type is the nearest approach to a living room, but is rarely specialized for this sole use.

4. Milling rooms: In these inclosures, often covered, but generally without roofs, we commonly find a mill for grinding corn, and sometimes a fireplace for frying paper bread or "piki." A room for this latter use is sometimes differentiated from the milling room. Cooking was done out of doors, either in a secluded corner of the court or on housetops; several rooms have corner fireplaces.

5. Circular rooms: These rooms are sometimes lookouts, but as often dedicated to ceremonials.

In addition to those mentioned above, there exist also inclosures of various forms, especially where we have circular kivas set in the midst of a mass of rectangular chambers. All types of rooms above enumerated are not found in the excavated pueblo, but when present they appear to reproduce essential features characteristic of cliff dwellings. As a rule, all the different varieties are larger in the open-air ruins than in the caves, where the protection of a natural roof makes open, outdoor life more agreeable and convenient.

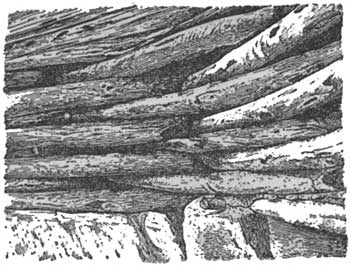

Wooden beams of floors and rafters of roofs, very much decayed, were found, especially in the rooms north of the large kiva. The ends of well-preserved cedar floor logs of a basal room protruded into one of the rooms north of kiva B.

CEREMONIAL ROOMS. KIVAS.

The well-known prescribed characteristic of cliff-house kivas— depression wholly or partially underground—is preserved in the pueblo by building rooms about their outer wall. The kiva floor is not at a lower level than the floors of surrounding rooms, but the walls of other rooms inclose the kiva, and thus sink it to all intents below the surface. This condition, which occurs in some of the kivas of the cliff dwellings, was universal at the Mummy Lake ruin.1

There were no windows in any of the kivas, and entrances were by hatchways in the roof. The surface of a kiva roof was too small for courts; the ceremonial dances probably took place within the inclosure on the south side of the pueblo. The method of construction of all the kivas is alike; they were roofed the same way (fig. 4).1 The central kiva is much larger than the remaining three, suggesting the name "assembly kiva," it being possible that instead of serving as the ceremonial room of a single clan, it was the room of a priest fraternity composed of several clans, or even an assembly place of all the people of the pueblo, reflecting a more advanced sociologic condition than in cliff houses and more like that found among pueblos of the Rio Grande, where we have but two kivas for the whole population.

1The Hopi kiva is constructed underground because tradition declares that it symbolically represents the underworld from which the ancients emerged into the present world. This esoteric prescript was also religiously observed by cliff dwellers so rigidly that when necessary the floor was excavated in solid rock.

FIG. 4.—Beams of kiva roof resting on a pilaster. |

As shown on the accompanying ground plan (fig. 1), the three small kivas are constructed on the same general plan as the kivas of Spruce-tree House and Cliff Palace. All have six pilasters for the support of a vaulted roof, and in some of these kivas the charred remnants of the rafters still remain. The most eastern and northern kivas (B, C, D) show evidences of a conflagration. The amount of smoke on the plastering of the walls is greater than would appear on the plastered walls if the roofs had not been burnt; moreover, the surfaces of the walls are colored bright red. The central kiva, A (pl. 12), is constructed on the same general lines as are the small kivas. It likewise had a vaulted roof supported on pedestals, a fireplace, ventilator, and deflector. No ceremonial opening or sipapu1 was detected in the floor of this kiva, which is also true of B and C; kiva D has the neck and part of the handle of an earthen cup set in the east wall forming a hole just below the level of the top of the banquette. When seen from the top of the room this insertion resembles a metallic pipe, for which it is often mistaken by visitors. Whether or not the opening represents a ceremonial orifice is not known, but if it does this is the only instance known to the writer where a Sipapu of this kind is found in a side wall and not in the floor between the fire place and the kiva wall opposite the deflector.

1The opening in the kiva floor called the sipapu is still used in Hopi ceremonials, through which to communicate with the underworld where a ghostly company of the dead are supposed to live engaged in the same occupations as when alive.

The construction of a vaulted roof over a room 32 feet in diameter was certainly a feat for stone-age masons that is worthy of more than passing notice. Naturally the writer could not believe this possible without the introduction of upright supports resting on the floor near the middle of the room. No evidence of such verticals was found and no depressions in the floor for their insertion about the fireplace were observed. It seems, therefore, that the masons accomplished the vaulting by logs resting on peripheral pedestals (fig. 4), as in smaller kivas.2

2The method of construction of a vaulted kiva roof in a Mesa Verde cliff house is shown in a restoration at Spruce-tree House, taken from a portion of a roof still preserved in square Tower (Peabody) House. The illustration in the text above was drawn from a photograph of the last mentioned by Mr. Gordon Parker, supervisor of the Montezuma National Forest.

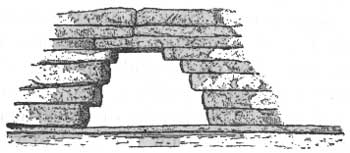

The cliff dwellers are said to have been unacquainted with the arch and keystone, but they were not unfamiliar with the so-called Maya arch. The masonry about the entrance into the ventilator (fig. 5) of the large assembly kiva, A, recalls this form of arch and is unique in the construction of Mesa Verde ruins. It consists of a flat slab of stone forming the top resting on other stones, each set a little back from the one above it, making a form of arch, but not the keystone type, which, so far as known, is absent in Mesa Verde buildings.

FIG. 5. Maya arch in flue of kiva A (Schematic) |

It may be said that on the whole the best masonry is found in the kiva walls, as is true in other types of buildings. The indications are that the large central kiva, A, is the oldest and that the other three, embedded in surrounding rooms, were later added to its outer walls. Changes in the walls and reconstruction of sections of the same were made after the original foundations were laid. This is especially noticeable in the position of the supports of the roof. Evidently the roof of the great kiva fell in before those of the smaller.

SECULAR ROOMS.

Besides the circular kivas this pueblo has many chambers which were secular in character, crowded about the ceremonial rooms. Among these the rectangular form predominates, although the intervals left between some of their walls and the outer kiva walls are inclosures of triangular or other shapes (see pl. 13). These recesses often have doorways but were not used as rooms, as is also indicated by the fact that the wall is jagged and destitute of evidences of chinking or plastering.

PLATE 12. CENTRAL KIVA, SHOWING MOUND 2 BEYOND WAGON, LOOKING SOUTH FROM P. 2, ON GROUND PLAN, FIG. 1. PHOTOGRAPH BY T. G. LEMMON. |

PLATE 13. CENTRAL KIVA, LOOKING WEST FROM P. 3 ON GROUND PLAN, FIG. 1. PHOTOGRAPH BY T. G. LEMMON. |

PLATE 14. 1 (top). ROOMS SOUTHWEST OF KIVA A, FROM SOUTHWEST ANGLE. PHOTOGRAPH BY T. G. LEMMON. 2 (bottom). SOUTHEAST ROOMS, FROM KIVA D TO SOUTHEAST ANGLE. PHOTOGRAPH BY T. G. LEMMON. |

PLATE 15. SPRING HOUSE, SHOWING NATURAL BRIDGE. PHOTOGRAPH BY GEORGE L. BEAM. |

It may be seen, in the ground plan, that there are no courts or open passageways running between the rooms in the pueblo, and that the partitions are made compactly, forming a solid mass of buildings.

The rooms, as a rule, are larger that those of cliff dwellings. Their entrances are higher and broader, generally rectangular, but there are two doorways situated back of the large kiva, apparently in a third story, which are T-shaped like those in cliff houses, opening out over the roof of this kiva. There are no external, lateral doorways in the north, east, and west walls, and but three instances where rooms open directly on the court through the south wall. The evidences of a third story are confined to the north side, which suggests a terrace to the south; but as all the rooms are not excavated it is not possible to determine whether or not three-storied rooms are limited to this section or how extensively a terraced form characteristic of a large pueblo was followed. The smoke on the walls of several rooms above corner fireplaces, the abundance of household utensils, as pottery and other objects, show that the pueblo was once inhabited and that people dwelt in the buildings many years.

Nowhere is the plastering so well preserved as in the walls of kivas between the floor and the level of the tops of the pilasters. The stratification of this plaster recalls a custom among living pueblo people. It is customary annually in February for the Hopi girls to replaster all the kivas, an episode which forms a part of lustral rites that pervade the Powamu or purification from the evil god who has control of the fields in winter. A somewhat similar ceremony may have taken place in the Mesa Verde pueblos. The successive layers of smoked clay are indicated on sections of plaster from the wall of kiva B, and number at least 20. This kiva had been plastered 20 times.

On the floor of a second-story room, below those in which are the T-shaped doorways, were found slabs of stone set upright forming a grinding bin, in which a grinding stone or a metate was found in place. In the west corner of the same room the walls showed marks of smoke and an arrangement of stone slabs indicating a fireplace.

REPAIR AND PRESERVATION OF WALLS.

As has been pointed out in an account of Sun Temple,1 the destruction of the walls of ruins standing under the open sky is largely due to violent rains or the infiltration of snow water and its subsequent freezing. To obviate this destructive agency the tops of all walls in Sun Temple were covered with Portland cement laid on adobe with a foundation of broken stones or rubble. This precaution has been found to accomplish the required results. Not a rock of the walls of Sun Temple fell from its place in the winter of 1915. The tops of the walls of the kivas of the pueblo excavated during the summer of 1916 were treated in much the same way, except that a coarse groat was added to sand in the cement.

1Excavation and Repair of sun Temple, Mesa Verde National Park. Department of the Interior, 1916.

In the repair work at Far View House it was necessary also to add a few courses of masonry to the tops of the exposed walls, and to prop up the outer walls on the west and south side with buttresses. The largest of these buttresses appears as steps on the west outer wall, which leaned so much that it certainly would have fallen as soon as uncovered if not held up in this way. This buttress was constructed about fallen walls.

To prevent the partition walls on the west tier of rooms from falling when their supports were removed their west ends were tied with new masonry to the inner side of the west wall. This was done with adobe and will be effective for a few years only. The tops of all walls ought to be covered with Portland cement.

In order to show the extent of the repair work on the tops of the walls the added courses were set a little back of the original wall, a method adopted from European archeologists.

Opinions may differ as to the amount of new masonry allowable in the repair of our ancient ruins, but the fact still remains that unless the walls are protected they will fall in a few years into piles of stone. To prove that statement one need only inspect excavations where no repair work has been done.

The amount of the appropriation was so small that it was not possible to treat all the walls in the same manner, much to the writer's regret.

CEMETERIES.

Although no excavations were attempted for the sole purpose of finding human bones,1 an almost complete skeleton of an adult was excavated from kiva B, about 6 feet below the surface. This skeleton was without pottery and showed no evidences of having been previously buried with pious care, the distribution of the bones suggesting a secondary hurried interment, possibly some time after the pueblo was deserted. Skeletons were not found under the floors.

1It may be well to call the reader's attention to the fact that this article is intended to deal only with cultural features upon which the pueblos have been differentiated from other stocks of American Indians.

A low mound in which the dead were systematically buried, called the cemetery, is situated near the southeast corner of the building, a few feet from the east and south walls. As with the cemeteries of all members of the Mummy Lake group, this mound had been trenched and its contents removed many years before the writer began work, evidences of broken mortuary vessels left by the workmen being abundant over the surface. A few skulls and larger bones were removed from the cemetery south of the pueblo, but there remained with the dead no whole pieces of pottery, so successfully had the graves been rifled by my predecessors. The bodies found were flexed or bent in a contracted position.

MINOR ANTIQUITIES.

As stated above, the two factors available for a knowledge of the history of a people ignorant of letters are buildings and smaller movable antiquities, such as pottery and other objects. We have already treated the former factor, and there remains to be considered the latter, embraced in the term "minor antiquities." So far as relics go, information drawn from these supports the conclusion derived from architecture, but a consideration of their significance in all its bearings must be left to a more exhaustive technical discussion than is here possible.

During the removal of earth from the rooms a large number of these small objects were found, but in the present paper it is impossible to do more than consider a few of the many relics excavated in the course of the summer. The majority of the objects came from the floors and in débris of the rooms, but a number were picked up outside the walls. These objects are practically identical with those found in cliff dwellings, indicating a similarity of culture notwithstanding there is a noticeable variation, especially in designs used in pottery decoration. Many duplicates of stone objects, as metates, manos (hand stones), pecking stones, mortars, and the like, were gathered together and left in a conspicuous place where they could be seen by visitors, but the majority, and all unique objects, were brought to Washington to be deposited in the National Museum, as required by law.

Several of the smaller stones with incised figures were set in cement on the south wall about midway in its length near the ladder recess; other larger stones and some with incised figures were arranged on the deflectors of the kivas, where they can readily be inspected.

Many visitors commented on the large number of household implements found here as compared with the paucity of the same at Sun Temple. The explanation of this fact is apparent, for the open-air house was inhabited for a considerable time while Sun Temple never had a population. The scarcity of wooden implements, basketry, and woven fabrics of various kinds is probably due to the exposure of the rooms after they were deserted. Objects of this kind left behind long ago decayed; in some rooms there is evidence on the walls of an extensive conflagration which would have destroyed everything inflammable.

STONE IMPLEMENTS.

A good series of stone hatchets and stone mawls was excavated from the rooms. These are generally grooved and polished, sometimes with sharp edges, although hatchets with rough surfaces and those with blunt edges worn down by hammering are also numerous. A few blades, possibly knives, are very finely chipped. There should also be mentioned well-made arrowheads and half a dozen well-fashioned spear points, but none of these have shafts. Celts called tcamahia, peculiar to cliff dwellings, were also found. A stone club unlike any weapon previously reported from the Mesa Verde was found on the surface.

PECKING STONES.

A very large number of implements that were formerly used in dressing the stones of the masonry were naturally excavated both inside the rooms and outside the walls. Some of these had pits on the two opposite faces and were pointed, others were girt by a shallow groove midway in their length. They were made of a much harder stone than that composing the walls of the building and were evidently brought from a distant locality, probably from the Mancos River. One of these made of hematite was more angular than the others. It would appear that these pecking stones were sometimes furnished with a handle.

The many stone mortars and pestles, some of which were much worn, and the numerous metates and manos are instructive. There were also found flat stones on which pigments were ground, and the iron oxides used for paint were not missing. All of these objects are identical with those from the cliff houses and add their quota of evidence to that contributed by the ceramics and architecture, that the pueblos and cliff dwellings of the Mesa Verde were inhabited by people whose cult objects were identical in character.

BONE IMPLEMENTS.

The assortment of bone implements, dirks, needles, bodkins, and the like is instructive. They vary in form, in kind of bone, and other particulars. It is rare to duplicate a perforated needle, one of which was found in kiva A. The skin scraper made of a bear bone is the same as those reported from Cliff Palace. The sections of small bones cut off in a cylindrical form are probably ornaments. Their shape resembles those from Spruce-tree House, suggesting that they were strung on a cord worn about the neck.

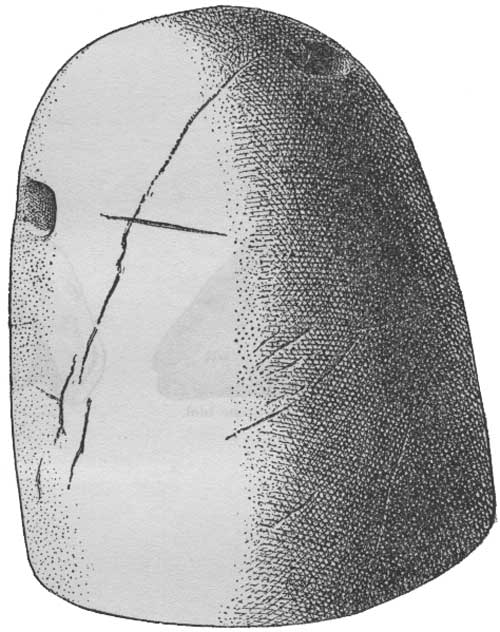

ANIMAL FIGURINES.

At least three different forms of stone idols were found, all buried in kivas. In the ventilator of kiva D one of the workmen discovered the head and part of the body of a quadruped made of sandstone, which resembles a bear's head. Another figurine of the same soft stone had head, eyes, and ears fairly well made, but the body elongated and angular, destitute of both legs and tail. The third specimen (fig. 7) was pointed at one end, rounded at the opposite with flat side or base, reminding one of the clay image of the Horned Serpent made at the winter solstice ceremony1 at Hano, one of the villages on the East Mesa of the Hopi, This striking likeness more than anything else has led me to suspect that it is an idol.

1Winter Solstice ceremony at Hano: Amer. Anthrop., Vol. I, No. 2, 1899.

CORN FETISHES.

In previous reports on Cliff Palace and Oak-tree House the writer called attention to certain half-oval stones found in kivas that he identified as idols or fetishes. They represent the magnified end of an ear of corn, and resemble specimens made of clay or wood still used in Hopi ceremonies, where they are called kætukwi, corn hills; they are in reality idols of Muyinwu, the god or goddess of germination. When wooden forms are used, symbols of corn of different colors are painted on them, or when made of clay a mosaic composed of kernels of different colored corn is regularly arranged on their surface. They are placed by the Hopi on the floor of the kiva before the altar and from time to time are sprinkled with prayer meal. Two stone specimens were found in the ruin, both of which have the same general form as that from Cliff Palace; one (fig. 6) is covered with a white substance like meal; the other has, near its apex, two small holes of about the diameter of a lead pencil.

FIG. 6.—Corn fetish. |

POTTERY.

Ceramics as well as architecture presents important evidences of racial culture and the acquisitions from the pueblo, Far View House, are particularly significant. We have extensive collections of pottery from cliff dwellings, but no specimens have been described from the open-air ruins of the Mesa Verde. It is therefore a pleasure to the writer to be able to add to our material the first collection from one of the Mummy Lake mounds1 that has ever been deposited in the National Museum.

1A considerable amount of "pot hunting" has been done in the cemeteries of this group, in which many specimens of mortuary pottery have been found and later sold to various museums. These are now labeled, "Mancos" or "Mesa Verde," and are useless for a study of the differences in individual cliff houses or comparisons between Mesa Verde pueblos and cliff dwellings.

This pottery is practically the same in form, color, and symbolism as that from the cliff dwellings, and supports the evidence of the architecture, that the ruin is prehistoric and comparatively old. It belongs to those archaic generalized types, widely scattered over the Southwest, which antedate specialized and more modern varieties. We find a large proportion of indented, coiled, rough ware, white with black decorations, and a few specimens of imported red with black figures. The figures on the last mentioned are mainly geometric, linear predominating, with curved designs but no life motifs, human or animal. There were comparatively few whole vessels.

ANIMAL REMAINS.

Portions of animal skeletons were found in considerable numbers, especially in room 26, which was evidently a dump place and filled with débris. Skeletal rejects found here may logically be supposed to reveal the character of the animal food of the natives, but the bones have not yet been fully identified, so that conclusions based on them must be tentative. We are, however, justified in saying, in this preliminary account, that bones of birds, and quadrupeds, such as rabbits, deer, antelope, mountain sheep, and elk, are perhaps the most common. Judging from the number found, it would appear that meat formed a considerable part of their diet, but the indications are that the inhabitants were primarily vegetarians, subsisting mainly on corn, beans, melons, and various wild fruits and herbs, pin˜on nuts in season, and other products, many of which now grow wild on top of the plateau.

CONCLUSIONS.

We can not say, without more extensive excavations, how much variation may exist in the forms of Mesa Verde pueblos or the arrangement of rooms in them, but all the mounds superficially examined show as a constant feature a marked central depression, apparently indicating a large kiva around which were arranged other and smaller rooms. We find surface indications of the presence of all forms of secular and small circular sacred rooms, from a tower "with rooms arranged around its outer wall" to round kivas embedded among square rooms. The peripheral wall of one or two impart a circular form to the mound; that of others, a rectangular outline.

The theoretical signification of the mounds on the Mesa Verde plateau has not escaped the attention of Baron Nordenskiöld who arrived at this interesting conclusion which the present writer's excavations prove:

Much may be said in favor of the opinion that the villages on the mesa and the cliff dwellers are the work of the same people, though no positive proof of this can be given. * * * As far as can be gathered from the heaps of ruins that now mark the site of these villages, the walls are constructed in the same manner as the best built parts of the Cliff Palace or Balcony House, of hewn stone in regular courses. The arrangement of the rooms, the plan of the building, etc., can not be ascertained without extensive excavations, for the execution of which I had no time. The far more advanced stages of decay attained by the ruins may possibly be adduced as evidence of their great age.

The evidence offered by Baron Nordenskiöld to support the theory that the cliff dwellings were abandoned and subsequently repeopled is not as strong as might be desired.

It is very probable [writes Nordenskiöld, whose honored name will always be associated with the Mesa Verde] that some of the cliff dwellings were inhabited contemporaneously with the villages in the open, and perhaps even later than they. This is suggested by the excellent state of preservation shown by some of the former, for instance, Balcony House. We are forced to conclude that they were abandoned later than the villages on the mesa. Some features, for example, the superposition of wails constructed with the greatest proficiency on others built in a more primitive fashion, indicate that the cliff dwellings have been inhabited at two different periods. They were first abandoned and had partly fallen into ruins, but were subsequently repeopled, new walls being now erected on the ruins of the old. The best explanation hereof seems to be the followng. On the plateaus and in the valleys the Pueblo tribes obtained their widest distribution and their highest development. The numerous villages, at no great distance from each other, were strong enough the defy their hostile neighbors. But afterwards, from causes difficult of enunciation, a period of decay set in, the number and population of the villages gradually decreased, and the inhabitants were again compelled to take refuge in the remote fastnesses. Here the people of the Mesa Verde finally succumbed to their enemies. The memory of their last struggles is preserved by the numerous human bones found in many places strewn among the ruined cliff dwellings. These human remains occur in situations where it is impossible to assume that they have been interred.

The supposition that the cliff dwellers were exterminated by their enemies in their eyrie homes appears to the writer improbable; nor is there ample proof that such a catastrophe as that mentioned in the closing lines of the above quotation took place while they inhabited the plateau. The "numerous human bones found in many places strewn among the ruined cliff dwellings" admit of another explanation. The disjointed skeletons may have been left there by "pot hunters" who tore them out of their graves and sacrilegiously strewed them over the floors of the rooms. The writer does not believe all the aborigines of the plateau were destroyed in or near their cliff dwellings or on the plateau. He holds the opinion that they migrated in groups large or small to the plains. The Utes, their enemies, have a tradition that they fought and killed many of the ancients inabiting the valleys at Battle Rock, near the Sleeping Ute Mountain at the entrance to the McElmo Canyon.

In a comparison of the pueblo above described with cliff dwellings protected by the natural roof of a cave (pl. 12) the amount of denudation of walls should have little weight in determining chronology, for the wear resulting from rains beating on the walls is reduced to a minimum in the latter case, while in the former it is very great. The walls of pueblos built centuries later often suffer much more erosion than cliff houses in the same length of time.

The relative excellence of the masonry is also not a safe chronological guide, for it degenerates as well as improves with successive generations of workmen. Poor masonry generally but not always antedates good masonry. The houses in Hopi villages, still inhabited, are not as well made as those of buildings now in ruins, in which they say their ancestors lived. If legends are reliable the skill of the Hopi masons has deteriorated; they have lost the ability they once exercised. Thus it by no means always follows that the walls of a well-made pueblo ruin are necessarily more modern than one with ruder walls. These considerations throw doubt on the theory that the character of masonry or the amount of erosion are good criteria by which to determine the relative age of pueblo buildings and cliff dwellings.

The second question, "How old are the cliff dwellings?" is impossible to answer, but we know that cliff dwellings were not inhabited in historic times. Comrades of Coronado, in 1540, left no records of cliff dwellings in New Mexico, but Castañeda mentioned many inhabited pueblos, which is an argument in support of the theory that the latter was a phase of architecture subsequent to the cliff house. No light is thrown by the writer's excavations on relative chronology, for no one can tell the age of either type of ruins in the Mesa Verde; nor is it possible to say that the buildings at Mesa Verde are older or younger than some of the Chaco, Animas, McElmo, or Montezuma Valley ruins, although the walls of the pueblos on top of Mesa Verde are as a rule worn down more by the elements than are those in the valley and therefore of a greater antiquity. The annual erosion of an artificially exposed wall on Mesa Verde is probably about the same in extent as in case of walls in the valleys mentioned. Since, as a rule, the walls of the latter stand higher out of their mounds, the logical conclusion would be that the higher walls are more modern than the lower, but other facts must also be considered before this can be stated as a law.

In a general way we can explain the supposed later construction of pueblos in the San Juan or its tributaries by the theory that their ancestors lived on the Mesa Verde, and that they left their ancient homes and settled in the Mancos or Montezuma Valley, whence they later spread down the river to distant points, as far as evidences of their culture can now be traced. This would seem a more natural conclusion, considering all the facts, than the theory, formerly advocated by the writer, that pueblos were developed in the river valleys before the ancients went on the mesa.

The likeness of the pueblo excavated to the open-air community houses along the San Juan and its tributaries is close enough to indicate identity of culture. As long as we were unacquainted with the essential features of the pueblos on the plateau we were unable to make close comparisons with adjacent cliff houses. The resemblances of community houses 100 miles distant from the cliff dwellings were known to be close, but the pueblo excavated furnishes us with a connecting link in our chain of similarities near at hand and on that account is of preeminent importance in a cultural comparison.

The resemblance between the pueblo on Mesa Verde and those of the McElmo and Montezuma Canyons, and the similarities to buildings in the La Plata and Animas Valleys have long ago been recognized as a likeness of culture, but whether the latter are older or more modern than the Mesa Verde pueblos is still one of the many unsolved problems awaiting additional research.

If the plateau building excavated owes its form to a survival of that developed in caves, it is therefore evidently of later construction and this would indicate that the pueblos of the San Juan and its tributaries are also of later date than the cliff dwellings, or, in other words, that architectural characteristics of Mesa Verde pueblos were originally formed in cliffs and the congested forms there produced were later transmitted to the valleys.

The Mesa Verde pueblo presents no certain evidence that its type of building is more modern than the cliff-house phase, but if the above conclusion be correct a natural corollary would be that identical open-air community houses in the San Juan and its tributaries were settled subsequent to the cliff dwellings of which the Mummy Lake settlement is a survival. Although we have no way of telling how old the Mesa Verde cliff dwellers or plateau habitations are in terms of the Christian calendar, the writer, unlike some other archeologists considers them comparatively modern; which does not mean, however, that man has not lived on the mesa in some degree of culture for a long time previously, but only that he was not a cliff dweller or a Pueblo Indian several thousand years ago. We have some evidence of the existence of a pit-house culture, with certain kinship to the puebloan, but the age of this no man knows with any more precision than he does the cause which forced man originally to make any kind of a home in the secluded fastnesses of the Mesa Verde.

An answer to the last and most difficult of all questions, "What became of the inhabitants?" is implied in the preceding lines. The writer has held that the cliff dweller constructed a pueblo after he abandoned the caves, and believes man later moved to the valleys, where his culture still survives. This culture is most apparent among the least modified living pueblos, as the Hopi. Of course it is not claimed that individual clans migrated directly to the Hopi country from Mesa Verde, but their culture traveled down the San Juan River Valley and ultimately was brought to Hopi land.

It is certain that some of the Hopi clans lived in cliffs. The Snake people have definite legends that they once inhabited the great cliff houses of the Navaho National Monument Betatakin and Kitsiel. These Hopi legends, and similar stories found among other pueblos, are supported by many facts besides architectural and ceramic resemblances. Ownership in eagle nests near cliff ruins are claimed through inheritance by the Snake clans, because they were ancestral property. Water from the cliff dwellers' spring is still sought and used in some ceremonies of the Hopi for the same reason.1

1On a visit to Betatakin a large cliff house of the Navaho Monument, in northern Arizona, a few years ago, a Hopi courier, who was on a pilgrimage there to obtain water from an ancestral spring, told the writer, in sight of the ruin, that the ancestors of the Snake people once lived there. If the ancestors of the largest clan in Walpi once inhabited the cliff houses of the Navaho Monument, and if the cliff dwellers of the San Juan had a culture identical with them, can it reasonably be doubted that cliff dwellers transmitted their blood and culture to pueblos, where they still survive?

These and many other facts support the legends that some of the Hopi clans are descended from cliff-dwelling clans or those formerly living in pueblos near cliff dwellings.2 Not the least important fact supporting this statement is the identity in artifacts among the two peoples.

2A discussion of all the causes of the desertion of the Mesa Verde villages, cliff dwellings or pueblos would take me too far afield for this article. Little can be added to the able remarks by Dr. Prudden in his analysis of the influence of climatic changes. See loc. cit.

As the only other building situated under the open sky on the plateau is Sun Temple, it is natural to consider whether the newly excavated ruin throws any light on the purpose of this mysterious structure.

In general form there is no likeness between the two buildings, although certain details of masonry show the handiwork of a people in the same stage of culture. The Mummy Lake pueblo lacks the unity and dignity of the religious building and presents evidences of having been repeatedly patched, as if constructed at intervals by different masons, often unskilled workmen. Its walls have been shattered and repaired. Buttresses were constructed by the aborigines to prop it up in places before they deserted it, and, as a rule, the masonry is poorer. In Sun Temple we find two kivas in an open court separated by passageways from bounding walls; in the new ruin domiciliary and ceremonial rooms are massed or crowded together, the court being situated not within the main structure but extramural, surrounded by a wall on the south side.

There is a certain likeness in what has been designated the kiva of the annex of Sun Temple to the small kivas of the pueblo, but the arrangement and form of rooms about them are different. The ventilation of the Sun Temple kivas was accomplished in a different way. The secular rooms are larger, doorways higher and broader in the ruin excavated at Mummy Lake than in Sun Temple.

The writer desired to find decisive evidences in his field work at Mummy Lake supporting or denying that the name, Sun Temple, was well given to the mysterious ruin opposite Cliff Palace. In that hope he was disappointed, but not wholly. The work above briefly outlined confirms his belief that Sun Temple and Far View House of the Mummy Lake group of buildings were constructed by an aboriginal people in comparatively the same cultural stage as the cliff dwellers.

Far View House is a pure type of pueblo building, limited to prehistoric times, its essential differences from the mixed or historic type, characteristic of modern pueblos, being its compact form and circular kivas embedded in surrounding house walls.

It is desirable, now that the general features of one of these have been excavated, to extend the work to other neighboring mounds of the group. The writer hopes some day to see all these mounds excavated and repaired. The sight of a dozen large, well-constructed pueblos in an area half a mile long by a quarter of a mile wide would be as instructive as exceptional. The excavation and repair of this cluster of mounds would be a worthy task for any institution to undertake, fraught as it is with so many problems of archeological interest, but it would require an enthusiastic devotion to scientific research supported by a large sum of money and many months of arduous toil by skilled workmen.

FIG. 7.—Stone idol. |

fewkes/index.htm

Last Updated: --2010