|

Missouri National Recreation River Nebraska-South Dakota |

|

NPS photo | |

The Missouri River is the longest river in North America. It once had abundant braided channels, chutes, sloughs, sandbars, islands, aha backwater areas. Historically, the Missouri carried high loads of sediment, earning it the nickname "Big Muddy."

Wetlands may be created during major floods if the Missouri slices a new channel through the banks of a riverbend and diverts water into a natural containment area. Wetlands are nature's way of controlling floods and providing new habitats.

Sandbars are created when fast-flowing waters lose their energy while moving downstream and deposit sand and soils that are picked up from the river bottom and banks. Sandbars are a habitat for nesting terns and plovers.

Islands develop typically during floods when the river follows its older channel and breaks open a new channel to encircle a sandbar or piece of land. Islands are stable enough to support vegetation and a variety of wildlife, like eagles.

A Great American Riverway

The Missouri has a story like no other river. Beginning at the confluence of three tributaries at Three Forks, Montana, it flows southeast for over 2,300 miles before joining the Mississippi River a few miles north of St. Louis, Missouri. It was the great waterway of American Indians, fur trappers, Lewis and Clark, and early settlers. In the 1800s the river shared with the Oregon and Santa Fe trails the distinction of being one of the three main thoroughfares to the Far West.

For centuries this wild, unpredictable river transported tons of silt and rocky freight. Forced into much of its present course by glaciers the river rushed along their faces. Eventually, the glaciers receded. The river remained, continuing its job of transporting the Rocky Mountains to the Gulf of Mexico grain by grain. As it changed course, any permanence of its channel and banks was accidental. Its floodplain was a mixture of wetlands, sandbars, wet prairies, and bottomland forests.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition traveled along this section of the Missouri from late August to early September 1804, and again on their return trip in 1806. They explored landscape features like Spirit Mound, held a council with the Yankton Sioux, and wrote the first reports on pronghorns, mule deer, and prairie dogs, all previously unknown to western science.

Flooding—Doing What Comes Naturally During the time of westward expansion the Missouri River had a vast floodplain. It periodically overflowed its banks, creating new channels as the main one moved from side to side. A shifting channel was normal, especially below Yankton and downstream to the confluence with the Platte River. Typically, in April brief floods of one to two weeks occurred as a result of local snowmelt and spring rains. In June floods lasted longer and inundated larger portions of the plains when melting snowpack from the Rockies and rain from lower elevations swelled the Missouri beyond its banks.

Taming the Missouri—The Pick-Sloan Plan After a series of floods devastated farms and towns in the early 1940s, Congress enacted the Flood Control Act of 1944. A component known as the Pick-Sloan Plan called for construction of five dams along the Missouri. By the mid-1960s, after the dams were built and reservoirs filled, the river ceased to be the meandering and high sediment-carrying sculptor of scenery. Although seasonal floods no longer replenish the floodplains, dam-controlled fluctuations provide habitats for an amazing array of plants and animals.

Today two stretches of the Missouri River along the Nebraska-South Dakota border are vital remnants of the historic river. In 1978 and 1991 Congress preserved these free-flowing sections by designating them as the Missouri National Recreational River and adding them to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System.

American Indians

True pioneers along the Mnisose Wakpa (turbulent river) were the American Indians for whom the river valley was a highway and a home. It provided shelter, wild game, and garden plots of fertile soil. The "Great Circle" of life along the river followed seasonal patterns. Each season the river renewed the resources that supported those who lived here. Spring brought floods that fertilized the fields. Fruits, berries, and other wild plants became available in season. Migrating birds, spawning fish, roaming bison, and animals wintering along the river dictated the direction of the hunt. American Indians used fire to shape the river landscape. Fire stimulated the growth of new grass, attracting bison and other animals, and kept the land free of trees. When Europeans arrived here, they found a wild but human-touched landscape.

At the time of the first European contact in the late 1700s and early 1800s, the Siouan Ponca were living on the Niobrara River to the west. It is probable that the territory was also visited by Oto, Omaha, and Pawnee. Yankton Sioux were living on the north bank of the Missouri River.

Original Highway West

Spanish explorers in long, flat-bottomed boats (bateaux), followed by French and British fur traders, were the first Europeans to enter the Missouri basin. Americans followed in keelboats, then by steamboats, as the river formed the most practical route to the Great Plains. But the river exacted a price. Artist George Catlin observed that the snags and rafts made of huge trees on the "River of Sticks" presented "the most frightful and discouraging prospect for the adventurous voyageur." Snags, fire, and ice continued to devour boats until the end of the 1800s. The bends were the most dangerous, for here the snags accumulated.

Steamboat traffic largely disappeared after a devastating flood in March 1881. Towns appeared first on the Nebraska side, but only after the 1859 treaty with the Yankton Sioux did communities spring up in Dakota Territory. The 1862 Homestead Act encouraged settlement in both territories. The promise of 160 acres attracted Americans from the East and Europeans from abroad. Many settlers farmed in the river's rich bottomlands, although one wit commented that these farmers never knew whether they would harvest corn or catfish. Descendants of these Czech, German, and Finnish immigrants maintain a rich heritage today.

Restoring the Past

Today everyone and everything here has a stake in the Missouri River, and sorting things out can be a challenge. No single agency can decide alone how to preserve this important riverway. Federal, state, and local governments, tribal agencies, private landowners, and the people who depend on the river for jobs and recreation are working together to find ways to protect the river. Stewardship—saving the river and its natural and cultural resources for future generations—is critical for the river to retain its natural state.

Discover the River

Visit the Missouri National Recreational River for its refreshing water and premier boating, fishing, and canoeing. While here, you can also camp, hike, bike, hunt, tour powerhouses and historic sites, trace the Lewis and Clark expedition, visit a fish hatchery and aquarium, and observe wildlife.

Discover the possibilities—activities, directions, tips, and regulations—on our website.

Things To See and Do

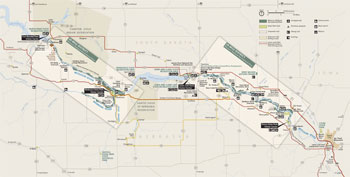

(click for larger map) |

Missouri National Recreational River comprises two free-flowing reaches of the Missouri River separated by Lewis and Clark Lake. The 39- and 59-mile districts lie on either side of the 98th Meridian—the eastern border of the Great Plains.

Heading west, Lewis and Clark noticed a change in the landscape: the woods receded, tailed off into tall grass prairie, then gave way to the short grass of the drier high plains. The abundant rainfall and large forested areas east of this north-south line of longitude are missing to the west. This change is increasingly noticeable west of the Niobrara River.

39-Mile District The western portion (Fort Randall Dam to Running Water, SD) has one of the best natural landscapes associated with the river along its entire course, including forested chalkstone bluffs and rolling hills.

59-Mile District The eastern portion (Gavins Point Dam to Ponca, NE) exhibits the river's historic, dynamic character in its islands, shallow bars, chutes, and snags.

Throughout the 39- and 59-mile districts, hiking and wildlife observation are available, including at Fort Randall Historic Site, Gavins Point National Fish Hatchery and Aquarium, Green Island, Bow Creek Recreation Area, Clay County Park, Mulberry Bend Overlook, and Spirit Mound. Hike, bike, or drive along scenic trails and byways at Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, Native American Trail, Oyate Trail, Outlaw Trail, and Shannon Trail.

Fishing and Hunting Walleye, bluegill, catfish, paddlefish, largemouth bass, and smallmouth bass are popular catches. In season hunters take geese, ducks, turkeys, pheasants, and deer. Licenses required.

Plan Your Trip

Plan ahead. Stop first at a visitor center. Open daily in summer. Limited off-season hours vary.

Fort Randall Dam Visitor Center is west of Pickstown, SD, along US Hwy. 281 and 18. View Lake Francis Case, Fort Randall Dam, and the Missouri River. www.nwo.usace.army.mil

Niobrara State Park, at the Niobrara-Missouri confluence, offers cabins, fishing, trails, camping, and National Park Service-led Ranger programs. 89261 522 Ave., Niobrara, NE 68760. www.outdoornebraska.gov

Lewis and Clark Visitor Center, downstream from Gavins Point Dam atop Calumet Bluff, has information, exhibits, a theater, a bookstore, and views of Lewis and Clark Lake and the Missouri River. PO Box 710, Yankton, SD 57078. www.nwo.usace.army.mil

Missouri National Recreational River Headquarters, open Monday through Friday 8 am to 4:30 pm, has park maps, Junior Ranger booklets, and passport stamps. 508 East Second St., Yankton, SD 57078. www.nps.gov/mnrr

Corps of Discovery Welcome Center sits near where Lewis and Clark Trail and Pan-American Highway (US 81) intersect. Scenic overlook, gift shop, exhibits, regional information. www.corpsofdiscoverywelcomecenter.com

Ponca State Park Visitor Center features vistas, forested hills, hiking, camping, and the Missouri National Recreational River Education and Resource Center. 88090 Spur 26E, Ponca, NE 68770. www.outdoornebraska.gov

Lodging and services are available :n nearby communities. Primitive tent camping in the park is at Green island and Bow Creek Recreational Area. Visit the park website for more information.

Enjoy a Safe Visit

Park Neighbors A mosaic of homes, tribal lands, communities, federal, state, and community parklands, and recreational facilities border the park. Please treat all property with care and respect.

Safety and regulations differ among areas managed by federal, state, tribal, local, and private agencies. Read bulletin boards and know the regulations—your safety is your responsibility.

Beware of snags, stumps, sandbars, and floating debris. • Always wear a life vest (PFD) when on the river. • Swimming in the river is discouraged because of unpredictable currents. • Personal watercraft (PWC), airboats, and drones are prohibited within the park. • Stay back from cliffs; large chunks of the riverbank can suddenly collapse. • For firearms regulations check the park website.

Contact parks about activities, facilities, fees, permits, regulations, reservations, and safety tips.

Accessibility We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. Visitor centers and state parks are generally accessible for visitors with disabilities. For information call, go to a visitor center, ask a ranger, or check our website.

Emergencies call 911

Source: NPS Brochure (2017)

|

Establishment Missouri National Recreation River — November 10, 1978 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Description of the Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics of the Niobrara/Missouri National Scenic Riverways (October 1993)

Final General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Missouri/Niobrara/Verdigre Creek National Recreational Rivers, Nebraska-South Dakota 39-Mile (June 1997)

Final General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Missouri National Recreational River, Nebraska-South Dakota 59-Mile (August 1999)

Fishes of the Missouri National Recreation Area, South Dakota and Nebraska (Charles R. Berry, Jr. and Bradley Young, extract from ©Great Plains Research, 14, Spring 2004)

Five Year Vision and 2013 Park Goals, Missouri National Recreational River (2012)

Foundation Document, Missouri National Recreational River, Nebraska-South Dakota (August 2017)

Foundation Document Overview, Missouri National Recreational River, Nebraska-South Dakota (January 2017)

Goat Island Management Plan and Environmental Assessment, Missouri National Recreational River, South Dakota and Nebraska (August 2019)

Junior Ranger Activity Book, Missouri River National Recreation River (2007; for reference purposes only)

Long Range Interpretive Plan (LRIP) Foundation Document, Missouri National Recreational River (MNRR) (Revised Draft March 22, 2011)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Missouri National Recreational River (2001)

Managing the Mighty Mo: Administrative History of the Missouri National Recreational River, Nebraska and South Dakota (Bruce G. Harvey and Deborah Harvey, Outside the Box, LLC, 2016)

Map (undated)

Master Plan for Reservoir Development, Gavins Point Reservoir, Missouri River, Nebraska & South Dakota Preliminar (December 1954)

Native American Cultural Resources: Missouri National Recreation River (John Ludwickson, Donal Blakeslee and John O'Shea, 1981)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Missouri National Recreational River NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/MNRR/NRR-2011/476 (Barry Drazkowski, Kevin J. Stark, Lucas J. Danzinger, Michael R. Komp, Andy J. Nadeau, Shannon Amberg, Eric J. Iverson and David Kadlec, December 2011)

Newsletters

"Current" News: Summer/Fall 2011 • Winter/Spring 2011-2012 • Summer-Fall 2012 • Summer/Fall 2014

River Connection: Summer 2016 • Summer 2017 • Winter 2018 • Summer-Fall 2018 • Winter 2019 • Summer-Fall 2019 • Winter-Spring 2020 • Winter-Spring 2021 • Winter-Spring 2022

Northern Great Plains Network Water Quality Monitoring Design for Tributaries to the Missouri National Recreational River NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NGPN/NRTR-2013/783 (Barbara L. Rowe, Stephen K. Wilson, Lisa Yager and Marcia H. Wilson, July 2013)

Outstandingly Remarkable Values, Missouri National Recreational River, Nebraska, South Dakota (2012)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring Protocol for the Northern Great Plains I&M Network Version 1.01 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NGPN/NRR-2012/489 (Amy J. Symstad, Robert A. Gitzen, Cody L. Wienk, Michael R. Bynum, Daniel J. Swanson, Andy D. Thorstenson and Kara J. Paintner-Green, February 2012)

Recreation Reconnaissance Report, Oahe Unit, South Dakota (Kenneth R. Krbbenhoft, June 1960)

Superintendent's Annual Reports: 2011 • 2012

The Missouri National Recreational River: An Unlikely Alliance of Landowners and Conservationists (Daniel D. Spegel, extract from Nebraska History, 90, 2009)

Visitor Study: Summer 2012, Missouri National Recreational River NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/EQD/NRR-2013/645 (Marc F. Manni, Yen Le and Steven J. Hollenhorst, April 2013)

White-Nose Syndrome Surveillance Across Northern Great Plains National Park Units: 2018 Interim Report (Ian Abernethy, August 2018)

mnrr/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025