|

MOUNT RAINIER

Master Plan Preliminary |

|

THE PARK

NATURAL FEATURES

Mount Rainier, the mountain itself, formed by natural forces of unimaginable magnitude, is the prime resource. Visible from Puget Sound on clear days, the mountain dominates the skyline, rising more than 7,000 feet above a rugged Cascade foundation in solitary splendor. Aptly described as "an arctic island in a temperate zone," Mount Rainier is the fifth highest peak and supports the greatest single peak glacial system in the contiguous United States, covering 34 square miles of mountain slope. The mountain is a superlative example of the "composite" type of volcano, which consists of alternating layers of lava flows and volcanic ash and cinders.

In the geologic scale of time, Mount Rainier appeared on the scene recently, within the last half-million years. The last major eruption period occurred about 2,000 years ago. The dynamic forces of volcanism and erosion are evident today, most recently demonstrated by eruptions between 1820 and 1854, the Kautz Creek Mudflow of 1947, the Little Tahoma Rockfall of 1963, and the South Tahoma Glacial outburst floods of 1967 and 1971.

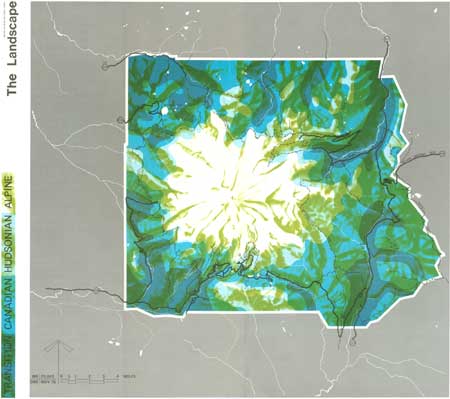

Climatic, topographic, and soil conditions combine to give Mount Rainier the richest plant growth of the Cascades. This vegetation supports a diverse variety of wildlife. An elevation range of 1,560-14,410 feet permits no less than four major life zones to occur. Over 700 species of vascular plants are present within the park, including spectacular virgin forests containing nearly 40 percent of the kinds of trees native to the region.

|

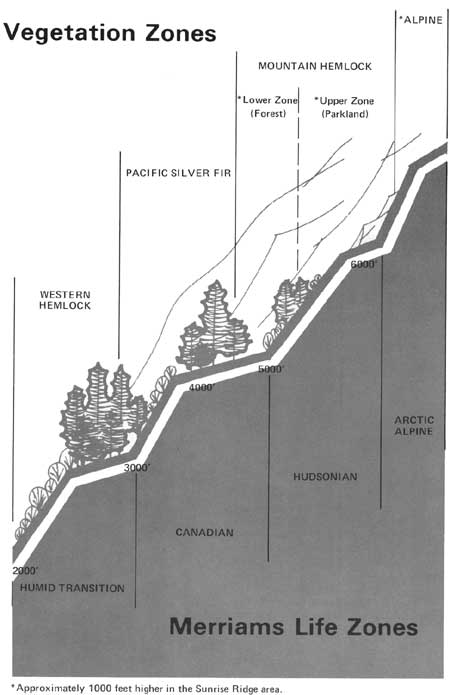

| Vegetation Zones |

Cathedral-like forest giants of Douglas-fir, western redcedar, and western hemlock occur primarily in the humid transition zone, while Pacific silver-fir, Alaska cedar, noble fir, and western white-pine appear in the Canadian zone. Spectacular subalpine flower fields laced by stands of mountain hemlock and subalpine fir dominate the Hudsonian zone. The harsh arctic alpine zone supports hardy alpine plants, including mosses and lichens, in areas free from ice and snow. The climax forests of western hemlock, Pacific silver-fir, and mountain hemlock; the Carbon River rain forest; and the arctic tundra of Burroughs Mountain are examples of prime resource areas within the park. Outstanding scenic features include Silver Falls, Comet Falls, and Narada Falls, Nisqually Vista trail, Box Canyon of the Cowlitz, historic Longmire Meadow, the magnificent Tatoosh Range, and the Grove of the Patriarchs.

Spectacular subalpine meadows and flower fields contribute to Rainier's world-wide reputation. Generally occurring between 5,000 and 6,500 feet, the panoramas of mountain flowers combine to make this region of the park the most popular. Because it is also the most fragile, maintaining a balance between its interpretation and its preservation has become extremely difficult.

|

| The Landscape. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Wildlife adds to the special attraction of Mount Rainier. Black-tailed deer, black bear, and mountain goat are popular natives numerous enough to permit frequent sightings by park visitors. Rocky Mountain elk were introduced into areas east of the park in 1912, and have subsequently increased their range to include many sections of the park. Cougar and coyote are other mammals also present in smaller numbers, while marmots and pika are fascinating inhabitants of several life zones, including the harsh arctic alpine zone.

Weather reigns supreme at Mount Rainier, and produces abundant precipitation in the midst of wide ranges in temperatures and wind velocities. Rain or snowfall occur on a majority of days. At Paradise during the winter of 1971-72, a world's record of 1,122 inches of snow fell. Frequently the mountain is concealed by a shroud of clouds that may persist for weeks or can quickly dissipate, leaving the lofty peak bathed in sunlight. Climbers attempting to reach the summit are often turned back by severe winds and freezing temperatures. These factors have proven fatal to inexperienced hikers in the arctic alpine zone.

The park receives frequent and prolonged storms, particularly in the fall and extending into the late spring. During late fall or early winter, heavy rains often follow a period of heavy snowfall below elevations of 7,000 feet. Rapid melting of the snow and flooding in the lower river valleys frequently causes extensive damage to trails, roads, bridges, powerlines, and buildings. The rugged topography and geologic hazards leave little area within the park that is adaptable for large-scale development without being exposed to potentially dangerous natural occurrences or requiring major alteration of the landscape.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Local Indians inhabiting the area surrounding Mount Rainier made annual hunting and berry-picking pilgrimages into what is now the park, and Indian legends about "The Mountain" contribute a colorful introduction to the human history of Mount Rainier. It is generally accepted that there were no permanent Indian villages within the park area, probably due to severe climatic conditions and religious feelings engendered by the massive peak.

Beginning with the botanical expedition of the British Doctor, W. D. Tolmie, to the Mount Pleasant area in 1833 and continuing for more than fifty years, friendly Indian guides assisted the Europeans in exploring the mountain and its environs. In 1857, the Nisqually Indian Wapowety guided the Kautz expedition to 14,000 feet. In 1870, Sluiskin, a Yakima Indian, guided P. B. Van Trump and General Hazard Stevens to the mountain, where they accomplished the first recorded ascent to the summit. "Indian Henry," a Klickitat, assisted George Bayley, Van Trump, and James Longmire in ascending the mountain in 1883, and his farm on the Yelm prairie became a favorite stop for those possessed of the "mountain fever."

In that same year, two prominent stockholders in the Northern Pacific Railroad visited an area that is now part of the park, suggesting that Mount Rainier be set aside as a national park.

In the years following, interest in a Mount Rainier National Park gained support. Included in those seeking such a goal was John Muir, who ascended the mountain in 1888 with Van Trump. Efforts of individuals, scientific groups, outing clubs, special committees, universities, and congressional representatives secured passage of a national park bill after considerable difficulty. President McKinley signed the bill into law on March 2, 1899, to make Mount Rainier the world's fifth national park.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

master_plan/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 10-May-2007