|

Mount Rushmore National Memorial South Dakota |

|

NPS photo | |

A monument's dimensions should be determined by the importance to civilization of the events commemorated...Let us place there, carved high, as close to heaven as we can, the words of our leaders, their faces, to show posterity what matter of men they were. Then breathe a prayer that these records will endure until the wind and the rain alone shall wear them away.

—Gutzon Borglum

It started as an idea to draw sightseers. In 1923 state historian Doane Robinson suggested carving giant statues in South Dakota's Black Hills. Robinson was not the first American to think that a big country demanded big art. As early as 1849, Missouri Sen. Thomas Hart Benton proposed a superscale Christopher Columbus in the Rocky Mountains. In 1886 the 150-foot Statue of Liberty was unveiled in New York. Now, in the 1920s, an unconventional sculptor named Gutzon Borglum was carving a Confederate memorial on Stone Mountain in Georgia.

Robinson wanted his sculptures to stand at the gateway to the West, where the Black Hills rise from the plains as a prelude to the Rockies. Here, granite outcroppings resist erosion to form the Needles, clusters of tall, thin peaks reminiscent of the spires on a Gothic cathedral. Robinson imagined the Needles transformed into a parade of Indian leaders and American explorers who shaped the frontier. Many people were skeptical or downright hostile. "Man makes statues," proclaimed local conservationist Cora B. Johnson, "but God made the Needles."

Undaunted, the memorial's backers called in the master sculptor of Stone Mountain. In an era when many artists scorned traditional patriotism, Gutzon Borglum made his name through the celebration of things American. To him "American" meant "big." Born in Idaho in 1867, this son of Danish Mormons studied art in Paris. Back home he worked in the shadow of his artist brother Solon even after several works brought Gutzon moderate fame. Among them were a remodeled torch for the Statue of Liberty, saints and apostles for the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York, a seated Lincoln in Newark, N.J., and an oversized Lincoln bust for the United States Capitol. In 1915 he began the Stone Mountain memorial, which gave him experience in large-scale carving—and in showmanship.

Borglum scouted out a location far better than the fragile Needles: 5,725-foot Mount Rushmore, named in 1885 for New York lawyer Charles E. Rushmore. Its broad wall of exposed granite faced southeast to receive direct sunlight for most of the day. Borglum's choice of subjects promised to elevate the memorial from a regional enterprise to a national cause "in commemoration of the foundation, preservation, and continental expansion of the United States." Borglum envisioned four U.S. presidents beside an entablature inscribed with a brief history of the country. In a separate wall behind the figures, a Hall of Records would preserve national documents and artifacts.

President Calvin Coolidge dedicated the memorial in 1927, commencing 14 years of work; only six years were spent on actual carving. Money was the main problem. It was here that Borglum's self-appraisal as a "one-man war" was earned. He personally lobbied state officials, representatives and senators, cabinet members, and presidents. "The work is purely a national memorial," he insisted at a congressional hearing in 1938. Pride in country—and the fact that public works created good jobs and good will—channeled $836,000 of federal money toward the total cost of nearly $1 million.

The Washington head was dedicated in 1930, followed by Jefferson in 1936, Lincoln in 1937, and Roosevelt in 1939. Borglum died in March 1941; the final dedication was not held until 50 years later. Son Lincoln Borglum supervised the completion of the heads. Work stopped in October 1941, on the eve of U.S. entry into World War II. Gutzon Borglum himself might have said that the time had come to defend the principles Mount Rushmore preserved in stone.

A Shrine in the Black Hills

Gutzon Borglum's vision for Mount Rushmore was no less than "the formal rendering of the philosophy of our government into granite on a mountain peak." Borglum chose to give human form to the abstract. His monument to America grouped four leaders who brought the nation from colonial times into the 1900s. Most prominent is George Washington, commander of the Revolutionary army and first U.S. president:

The preservation of the sacred fire of liberty, and the destiny of the Republican model of government are justly considered as deeply, perhaps as finally staked, on the experiment entrusted to the hands of the American people.

—George Washington, First Inaugural Address, April 30, 1789.

Next was Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence, third president, and mastermind of the Louisiana Purchase:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

—Thomas Jefferson, Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776.

To the far right was 16th President Abraham Lincoln, whose leadership restored the Union and ended slavery on U.S. soil:

Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.

—Abraham Lincoln, Address at Cooper Union, February 27, 1860.

The 26th president Theodore Roosevelt promoted construction of the Panama canal and ignited progressive causes like conservation and economic reform:

We, here in America, hold in our hands the hopes of the world, the fate of the coming years; and shame and disgrace will be ours if in our eyes the light of high resolve is dimmed, if we trail in the dust the golden hopes of men.

—Theodore Roosevelt, Address at Carnegie Hall, March 30, 1912.

Everyone wanted to see the men on the mountain. Gutzon Borglum regarded his masterpiece as far more than a tourist attraction. Consider the assessment of another man who made a name blending art and nature: "The noble countenances emerge from Rushmore," noted architect Frank Lloyd Wright, "as though the spirit of the mountain heard a human plan and itself became a human countenance."

More and more we sensed that we were creating a truly great thing, and after a while all of us old hands became truly dedicated to it and determined to stick to it.

—Red Anderson, Mount Rushmore driller and assistant carver

Creating Giants in the Black Hills

Sketches in Plaster

Borglum knew portraiture. In his youth he studied art in Paris with sculptor

Auguste Rodin. He boasted a roster of memorials to famous Americans, including

Gen. Philip Sheridan, Gen. Robert E. Lee, and Abraham Lincoln. Having read

avidly about Lincoln and been personally acquainted with Theodore Roosevelt,

Borglum was thoroughly prepared when the Mount Rushmore commission came his way

in 1925. He based the models on life masks, paintings, photographs,

descriptions, and his own interpretations. Plaster copies of the models were

always displayed on the mountain as a guide for workers. But Borglum did not

merely transpose the models directly into granite. The differences between the

models in the sculptor's studio and the heads on the mountain show how Borglum

fine-tuned the four granite giants into true works of art.

Inches to Feet

How to transfer the models to the mountain? Borglum's answer was his "pointing"

machine: The models were sized at a ratio of 1:12—one inch on the model

would equal one foot on the mountain. A metal shaft was placed upright at the

center of the model's head. Attached at the base of the shaft was a protractor

plate, marked in degrees, and a horizontal ruled bar that pivoted to measure the

angle from the central axis. A weighted plumb line hung from the bar; it slid

back and forth to measure the distance from the central head point, and raised

and lowered to measure vertical distance from the top of the head. Thus, each

point on the model received three separate measurements. The numbers were then

multiplied by 12 (angles remained the same) and transferred to the granite face

via a large-scale pointing mechanism anchored at the top of the mountain.

The Faces Emerge

The only shaping technique available to the carvers was the removal of the

stone. No material could be added. With such an unforgiving medium, Borglum at

first ruled out dynamite. He quickly changed his mind; the rock was so hard that

blasting was the only practical way to remove the huge portions of the weathered

face to reach solid granite for carving. After an egg-shaped volume of rock was

prepared for each head, the pointers went to work measuring for facial features.

Skilled blasters dynamited to within a few inches of a desired measurement. The

closer the blasters got to the finished surface, the more carefully Borglum

studied the heads, making changes as necessary. The most drastic change was the

relocation of Jefferson's head from Washington's right to left side because

there was not enough rock to complete the figure.

Finishing Touches

After blasting, the features were shaped by workers suspended by cables in swing

seats called Bosun chairs. First they used pneumatic drills to honeycomb the

granite with closely spaced holes to nearly the depth of the final surface.

Excess rock was then chiseled off. A blacksmith sharpened hundreds of drill bits

each day that dulled quickly on the rock. Later, the men "bumped" away the drill

holes and lines with pneumatic hammers to create a smooth, white surface. It was

attention to detail that gave humanity to the sculptures. Up close, the pupils

of the eyes are shallow recessions with projecting shafts of granite. From a

distance, this unlikely shape makes the eyes sparkle and brings the presidents

to life.

Planning Your Visit

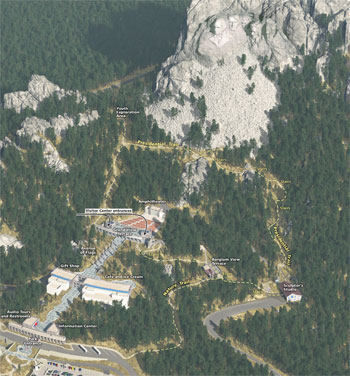

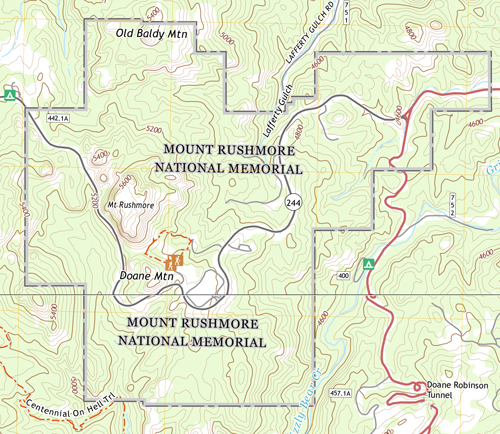

(click for larger maps) |

Parking Mount Rushmore has a concession-operated parking facility that charges a fee. The National Parks and Federal Recreational Lands Pass is not applicable for parking.

Facilities The information center and the Lincoln Borglum Visitor Center are open from 8 am to 5 pm in winter and until 10 pm in summer; hours vary in spring and fall. Begin at the information center, where staff and displays will help you plan your visit to the park and the Black Hills region. From here, go up the walkway toward the sculpture and other facilities. The Lincoln Borglum Visitor Center has exhibits on the carving of Mount Rushmore, a 14-minute film "Mount Rushmore—The Shrine," an information desk, restrooms, and a bookstore operated by the Mount Rushmore History Association. The Sculptor's Studio (closed in winter) displays models and tools used in the carving process. Programs are conducted here daily in summer. The concession building, open year-round, has food service and a gift shop.

Activities You can view the memorial from the roadside 24 hours a day, year-round. It is best viewed and photographed in morning light. The main developed area (including facilities) is open 6 am to 10 pm in winter and 5 am to 11 pm in summer. Viewing spots include the Grand View Terrace, Amphitheater, Presidential Trail along the Avenue of Flags, Borglum View Terrace, and near the Sculptor's Studio. The 0.6-mile Presidential Trail begins at Grand View Terrace, with access to viewing sites near the talus slope below the faces. The Evening Lighting Ceremony is held in the outdoor amphitheater daily in summer. The rest of the year the sculpture is illuminated at dusk for a couple of hours. Check schedules in summer for ranger-led programs.

Accessibility Most park grounds and facilities are accessible to persons with disabilities; assistance may be required on some trails. Accommodations can be made for access to lower areas. Service animals are welcome.

For a Safe Visit Please observe these regulations: • Climbing the mountain, feeding wild animals, and building fires are prohibited. • It is unlawful to collect plants, animals, and rocks or other natural materials. • Pets are prohibited in developed areas. • Stay on trails while walking. • Drive carefully on Black Hills roads. You must wear seatbelts in all National Park System areas. • Camping is prohibited in the park.

Location Mount Rushmore National Memorial is 25 miles southwest of Rapid City, S.Dak., via U.S. 16; and three miles from Keystone via U.S. 16A and S.Dak. 244. Major airlines and bus routes serve Rapid City.

While in the area you may wish to visit these National Park Service sites: Badlands and Wind Cave national parks, Minuteman Missile National Historic Site, and Jewel Cave and Devils Tower national monuments. Other areas include: Custer State Park, Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, Black Hills National Forest, and Buffalo Gap National Grassland.

Source: NPS Brochure (2011)

|

Establishment Mount Rushmore National Memorial — February 25, 1929 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Survey of Rock Climbers at Mount Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota Final Report (Maret S. Freeman, Leo H. McAvoy and David W. Lime, May 1997)

Archeological Assessment, Mount Rushmore National Memorial, 1973 (Adrienne B. Anderson, 1974)

Condition Assessment: Mount Rushmore National Memorial NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/WRD/NRR-2009/115 (Sunil Narumalani, Gary D. Wilson, Christine K. Lockert and Paul B. T. Merani, June 2009)

Exploring spatial patterns of overflights at Mount Rushmore National Memorial NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/MORU/NRR-2022/2410 (Brian A. Peterson, J. Adam Becco, Sharolyn J. Anderson and Damon Joyce, June 2022)

Fire and Forest History at Mount Rushmore (Peter M. Brown, ,Cody L. Wienk and Amy J. Symstad, extract from Ecological Applications, Vol. 18 No. 8, 2008)

Foundation Document, Mount Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota (September 2015)

Foundation Document Overview, Mount Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota (January 2015)

Flying Squirrel Distribution and Habitat Use at Mount Rushmore National Memorial NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/MORU/NRTR—2012/607 (Daniel S. Licht, Christi Bubac and Jane Swedlund, August 2012)

General Management Plan, Mount Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota (December 1980)

Geologic Resource Evaluation Report, Mount Rushmore National Memorial NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2008/038 (J. Graham, June 2008)

General Management Plan, Mount Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota (December 1980)

Gutzon Borglum's Concept of the Hall of Records, Mount Rushmore: Special History Study (Enid T. Thompson, June 1975)

Historic Resource Study: Shrine of Democracy and Sacred Stone, Mount Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota (Paula S. Reed and Edith B. Wallace, 2016)

Impacts of Visitor Spending on the Local Economy: Mount Rushmore National Memorial, 2013 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/EQD/NRR—2014/796 (Philip S. Cook, April 2014)

Interpretive Prospectus, Mount Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota (April 1992)

Junior Ranger (Ages 5-12), Mount Rushmore National Memorial (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only, ©Mount Rushmore Society)

Master Plan of Mount Rushmore National Memorial: Mission 66 Edition (1961)

Mount Rushmore National Memorial Junior Ranger (Ages 5-12) (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only, ©Mount Rushmore Society)

Mount Rushmore National Memorial Rushmore Ranger (Ages 13 and Over) (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only, ©Mount Rushmore Society)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Mount Rushmore National Memorial (Michael S. Lindberg, November 1984)

Mount Rushmore National Memorial Historic District (Additional Documentation and Boundary Increase) (Melissa Dirr Gengler and Liz Sargent, July 2013)

Park Newspaper (Mount Rushmore Voice): Summer 1987

Perchlorate and selected metals in water and soil within Mount Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota, 2011–15 USGS Scientific Investigations Report 2016-5030 (Galen K. Hoogestraat and Barbara L. Rowe, 2016)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring Protocol for the Northern Great Plains I&M Network Version 1.01 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NGPN/NRR-2012/489 (Amy J. Symstad, Robert A. Gitzen, Cody L. Wienk, Michael R. Bynum, Daniel J. Swanson, Andy D. Thorstenson and Kara J. Paintner-Green, February 2012)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring at Mount Rushmore National Memorial: 2011-2017 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/MORU/NRR-2019/1951 (Isabel W. Ashton, Christopher J. Davis and Daniel Swanson, July 2019)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring for Mount Rushmore National Memorial

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring at Mount Rushmore National Memorial: 2010-2012 Status Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NGPN/NRTR—2013/677 (Isabel W. Ashton. Michael Prowatzke, Michael R. Bynum, Tim Shepherd, Stephen K. Wilson and Kara Paintner-Green, January 2013)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring for Mount Rushmore National Memorial: 2013 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/NGPN/NRDS—2014/617 (Isabel W. Ashton and Michael Prowatzke, February 2014)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring for Mount Rushmore National Memorial: 2014 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/NGPN/NRDS—2015/766 (Michael Prowatzke and Stephen K. Wilson, March 2015)

Plant Community Composition and Forest Structure Monitoring at Mount Rushmore National Memorial: 2016 Data Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/NGPN/NRDS—2017/1103 (Molly Davis, May 2017)

Plant Community Composition and Structure at Mount Rushmore National Memorial: 2011–2017 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NGPN/NRR—2019/1951 (Isabel W. Ashton, Christopher J. Davis and Daniel Swanson, July 2019)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring at Mount Rushmore National Memorial: 2018 Data Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/NGPN/NRDS—2019/1200 (Ryan M. Manuel, January 2019)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring at Mount Rushmore National Memorial: 2019 Data Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/MORU/NRDS—2019/1243 (Ryan M. Manuel, November 2019)

Rushmore Ranger (Ages 13 and Over), Mount Rushmore National Memorial (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only, ©Mount Rushmore Society)

Sign Study, Mount Rushmore National Memorial (Anderson Mason Dale, August 1997)

Statement for Management: Mount Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota (August 1990)

Status of Forest Structure and Fuel Loads at Mount Rushmore National Memorial: 2010-2011 Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCCN/NRTR—2012/591 (Isabel W. Ashton, Michael Prowatzke, Michael R. Bynum, Tim Shepherd, Stephen K. Wilson, Kara Paintner-Green and Dan Swanson, June 2012)

Visitor Study: Summer 2013, Mount Rushmore National Memorial NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/EQD/NRR—2014/785 (Margaret Littlejohn and Yen Le, March 2014)

Water Resources and Geology, Mount Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota USGS Water-Supply Paper 1865 (J.E. Powell, J.J. Norton and D.G. Adolphson, 1973)

White-Nose Syndrome Surveillance Across Northern Great Plains National Park Units: 2018 Interim Report (Ian Abernethy, August 2018)

moru/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025