|

Nez Perce National Historical Park |

|

Big Hole National Battlefield |

|

Chapter 8:The National Park (continued) In reporting on his lengthy encounter with the Nez Perces, John Shively supplemented the important intelligence of their status given by Irwin. He said that the camp of 125 lodges numbered 250 warriors, but that the total population was between 600 and 800. There were two thousand horses, with each lodge's occupants responsible for its own animals. "Every lodge drives its own horses in front of it when traveling, . . . [and] the line is thus strung out so that they are three hours getting into camp." A few Crows had reportedly joined the body, as well as seventy-five Shoshones under Little Bear. (All of these people seemingly had left the group before the Nez Perces emerged from the park into Yellowstone Valley.) Regarding leadership, Shively said that "no particular chief seemed to be in command," and that "all matters were decided in a council of several chiefs." He had not knowingly seen White Bird, but Looking Glass was considered the "fighting man"; he noted that "Joseph would come in if it was not for the influences of the others." He described Joseph as "about thirty-five years of age, six feet high, and always in a pleasant mood, greeting him each time with a nod and smile. . . . Joseph wears one eagle feather." Shively further reported that the Nez Perces told him they had lost forty-three warriors in their battles to date. [49] The Nez Perces' prolonged contact with Shively and Irwin represented two of three encounters directly with the main body of the tribesmen as they passed through the park, the other, as indicated, being their involvement with the Radersburg party of tourists, beginning on August 24 in the Lower Geyser Basin. Whereas those with Shively and Irwin were purposefully and peacefully sustained by the warriors, the contact with the Radersburg group was brief—and violent. Their experience was also significant because their interrelationship with the Nez Perces gave knowledge about the tribesmen's early movements in the park. The Radersburg party—so-called because its members were from that community between Helena and Three Forks, Montana Territory—consisted of nine people: George F. Cowan, his wife Emma, her brother Frank D. Carpenter, and sister Ida Carpenter, besides Charles Mann and a young teamster, Henry ("Harry") Meyers—all from Radersburg—plus three friends of Frank Carpenter's from Helena, Andrew J. Arnold, William Dingee, and Albert Oldham. Leaving Radersburg on August 5, the party had entered the park on the fourteenth via Henry's Lake, Targhee Pass, and the Madison River and had followed a road leading to Lower Geyser Basin, finally establishing their permanent camp on the left bank of Tangled Creek and about one-half mile west of Fountain Geyser. [50] From that point they had toured the Upper Geyser Basin, and some of the group had gone over to see the Lower Falls and Yellowstone Lake. By August 23, the party had reassembled at the permanent camp, ready to start for home the next day. Camped nearby was William H. Harmon, a Colorado prospector who was to experience the subsequent events with the Radersburg party. They had settled in for the night, not knowing of the capture of John Shively a mile north of their camp. That night Nez Perce scouts, including Yellow Wolf, sighted the Cowans' campfire. At about 5:00 a.m. Friday morning, as Dingee and Arnold prepared breakfast, three tribesmen approached, dismounted, first identifying themselves as Shoshones ("Snakes") and then confessing that they were Nez Perces belonging to Looking Glass's band. They asked about soldiers in the vicinity, saying that they were friends of white men but would fight the soldiers. As the conversation continued, more warriors appeared in the distance, some strolling the adjoining area to watch the geysers. Initially, the Radersburg party, confronted with the warriors, tried to leave and began packing their baggage wagon. But the Nez Perce warriors requested food, which Arnold began to dispense to them until George Cowan intervened, stopped the disbursement, and probably angered the tribesmen. Hoping to avoid a serious confrontation, the tourists, joined by Harmon, harnessed their teams and saddled their four riding horses, then started down the Firehole with their two wagons (a double-seated carriage, or spring wagon, and a half spring baggage wagon) toward where the vast Nez Perce assemblage was moving up the East Fork of the Fire Hole (present Nez Perce Creek). Frank Carpenter described the procession:

Close to the mouth of the stream as many as seventy-five warriors on horseback blocked their way and directed them to follow the Indians. [52] "Every Indian carried splendid guns, with belts full of cartridges," remembered Mrs. Cowan. [53] At this point, Frank Carpenter demanded to see Looking Glass and was led away from the other members of the party for that purpose. [54] Two miles up the creek they came on so much felled timber that the wagon could not go on, whereon they took some provisions and blankets and headed after the Nez Perce camp accompanied by the warriors. Other men then tore into the wagon and its contents, destroying the vehicle by knocking out the wheel spokes to use in making quirt handles. The team horses were saddled for Mrs. Cowan and Ida to ride. Six miles farther east, near the foot of Mary Mountain, the entire body halted to eat, and there the tourists were reunited with Carpenter. There, Poker Joe—who the Cowan party initially thought was Joseph [55]told them that they would be released if they traded their horses, arms, and bedding for some of the Nez Perces' jaded mounts. Captive Charles Mann remembered that, after taking most of their guns, the Nez Perces "robbed us of what we had left," then began moving their procession again. [56] Poker Joe told the captives to go on their way, cautioning them, however, to get off the trail and into the woods and to beware some younger troublemakers among the people. "He seemed to act in good faith with us," recalled Mann. But as they started back, "they discovered that they were closely followed by forty or fifty of the worst looking warriors in the band." [57] After laboring among the fallen trees, however, most of the tourist party returned to the trail and shortly found themselves surrounded by the warriors, who started them east to the Nez Perce camp on the pretext that the chiefs wanted to see them again. Mann suggested that the warriors had become incensed when two men of the party, Arnold and Dingee, had bolted into the underbrush at their approach. [58] One or two miles farther east, at a point just past the earlier meal stop and at the base of Mary Mountain, the warriors paused the remaining members of the group and took the balance of their effects. George Cowan and his wife later described to a reporter what happened next:

Years later, Emma Cowan recalled looking up just before the warriors shot her husband in the head: "The holes in those gun barrels looked as big as saucers." [60] As the firing broke out, Charles Mann felt a bullet slice through his hat "without touching my hair." Albert Oldham, meanwhile, had been hit in the face, the bullet tearing through his cheeks without [major] injury to his teeth or tongue," but knocking him down. Instantly, he had turned on his attacker, pointing an empty rifle at him, and the Nez Perce bolted while Oldham dove into the brush, where he roamed for an agonizing thirty-six hours sustaining himself on crickets until rescued by Howard's column. Charles Mann likewise took to the bushes, lying there for four hours before finding his way back to the Lower Basin camp and then heading down the Firehole where the army scouts found him the next day. Mrs. Cowan and Ida Carpenter went unharmed in the melee. Frank Carpenter had also run into the brush, but when a warrior trained his gun on him, he made the sign of the cross and the warrior did not fire but took him captive. [61] Henry Meyers and William Harmon both fled into a marsh and hid among the reeds. Harmon was picked up the next day by Fisher and his scouts on the Madison six miles below its junction with the Gibbon and Firehole rivers soon after Mann was found. Harmon, "exhausted from hunger and fatigue," the next morning went down to join the command; Mann kept on with the scouts for four days searching for others of the party. Meanwhile, Arnold and Dingee, who had initially fled from the warriors, managed to get away through the woods after abandoning their mounts and eventually reached the Gibbon River. Henry Meyers found Howard's command at Henry's Lake and told of the presumed deaths of Cowan and Oldham at the hands of the Nez Perces. Dingee and Meyers soon departed for their homes via Virginia City, while Arnold stayed with the command. [62] In fact, George Cowan, having been shot, had afterwards been nearly brained by a warrior who struck the prostrate man on the head with a large rock. Left for dead, he came to within hours of his wounding, tried to stand upright, but was shot again—this time in the hip by a warrior lingering nearby. Cowan did not move, and after several Nez Perce men passed by driving horses without observing him, he waited awhile and then pulled himself along the ground by his elbows through the stream and along it for a distance of one-half mile. He alternately crawled and rested and, over the next four days, traversed about twelve miles. Near the place where the wagons had been abandoned, Cowan found his bird dog, who stayed with him through his subsequent journey. At one point in his travail, Cowan saw Fisher's Bannocks, but fearing they were Nez Perces, he remained hidden. Finally gaining the camp site at Lower Geyser Basin, he found a dozen matches, and with potential meat and fire at hand, and strengthened with some weak coffee he managed to brew in an old fruit can, Cowan rested overnight, then started back to the mouth of the East Fork of the Firehole, confident of being rescued. Howard's scouts with "Captain" Rube Robbins encountered Cowan on August 29 and were able to inform him that his wife and sister-in-law had been released safely. The next day, Howard's surgeon treated his wounds. Cowan, Oldham, and Arnold continued with the troops, but later departed for Bozeman via Mammoth Hot Springs and Bottler's Ranch. [63]

Probably because of the timely intervention of Poker Joe, the Nez Perces did no further injury to the remainder of the Cowan party, but kept the two grief-stricken women and Frank Carpenter with them until the next day. [64] In her narrative of the event, Mrs. Cowan recounted the passage of the Nez Perce procession up Mary Mountain on August 24 in a paragraph that probably described the character of the people's trek through the park:

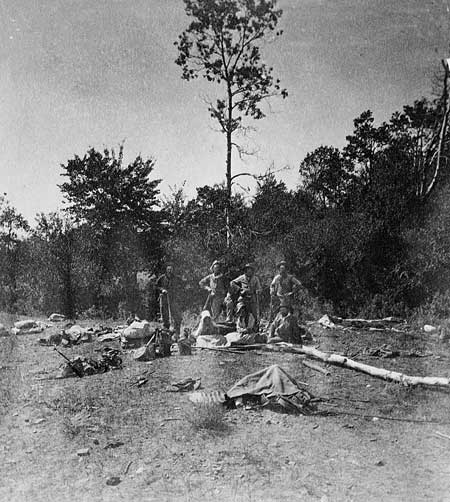

At the camp that night on the east side of Mary Lake, Emma Cowan noticed that the tribesmen lacked tipis and instead protected themselves from the cold and rain with pieces of canvas stretched between poles or over bushes in the form of rude wickiups. [66] Frank Carpenter remembered that the camp was "on the outer edge of a circular basin about three-fourths of a mile in circumference" with its perimeter dotted with campfires and in which many of the horses were corralled. [67] Carpenter also stated that he met Joseph that evening and that the Wallowa leader had expressed displeasure with the actions of his kinsmen in opening fire on the Radersburg people. [68] On August 25, following a council of leaders, the Nez Perces released Mrs. Cowan and the Carpenters from their camp on the east side of the Yellowstone above the Mud Volcano. "We did not want to kill those women," remembered Yellow Wolf. "Ten of our women had been killed at the Big Hole, and many others wounded. But the Indians did not think of that at all." [69] Given horses and clothing, and escorted by Poker Joe to the west bank of the river, the three kept to the timber as they went along, fearful of encountering more scouting parties. In their course, they crossed Sulphur Mountain in the evening and night of August 25. On the twenty-sixth, they forded Alum Creek, surmounted Mount Washburn, and passed through the camping grounds near Tower Fall before stumbling onto a detachment of Second cavalrymen from Fort Ellis commanded by Second Lieutenant Charles B. Schofield near present Tower Junction. The troops escorted the trio to Mammoth Hot Springs, and from there on August 27 they started down the road to Fort Ellis and Bozeman, with Emma Cowan eventually to be reunited with her husband following his own ordeal. [70] In his wire to Gibbon from Mammoth, Schofield reported intelligence, perhaps gleaned from Mrs. Cowan and the Carpenters, that the Nez Perces were en route to Wind River and Camp Brown for supplies; however, the lieutenant offered his own belief that they were headed for the lower Yellowstone by way of Clark's Fork. [71]

|

|

| ||

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

|

Nez Perce, Summer 1877 ©2000, Montana Historical Society Press greene/chap8b.htm — 26-Mar-2002 | ||