|

National Park Service

From Marsh to Farm The Landscape Transformation of Coastal New Jersey |

|

CHAPTER 5:

SALT-HAY FARMING

Though the Burcham farm is the last reclamation project of its type along the Maurice River, there is still some reclaimed land devoted to the production of salt hay along the Delaware Bay. In fact, the production of salt hay has become the current primary agricultural reason for preserving the reclaimed salt marsh. The Wetlands Act of 1970 bars the reclamation of new tracts of marshland, but does allow farmers to maintain what is already used for salt-hay production.

Salt hay grows naturally on all salt marshes along the Atlantic Seaboard including New Jersey's Delaware Bay and Atlantic Coast. Salt hay is a generic term for three different types of marsh grasses that grow at different elevations. The first is black grass (Juncus gerardi), a rush that grows on higher meadows and is cut by July before it becomes oily and black. Rosemary (Distichlis spicata) has a partially hollow stem and is found at slightly lower elevations, while yellow salt (Spartina patens) grows on even lower elevations still, and is considered the best type of grass for salt hay due to its finer qualities. [1]

Early Dutch and English settlers knew the value of this grass and harvested it as well as let their cattle graze on it. Jasper Danckaerts, a seventeenth-century Dutch traveler, described the salt-marsh meadows in New York and New Jersey as being mowed for hay even though at times it suffered tidal inundations. He observed that cattle preferred this salt marsh hay over fresh hay or grass. Adriaen van der Donck, a seventeenth-century resident of the New Netherlands, also commented on how sick cattle improved in health once set out on the marshes to graze.

Even in the late nineteenth century, New Jersey commentators such as the Reverend Allen H. Brown discussed the vastness of the marshes along the Delaware Bay and the Atlantic Coast and the opportunities they provided.

The salt marshes or salt prairies of the coast may be reckoned among the natural privileges, as they produce annually, without cultivation, large crops of natural grasses. The arable land comes down to the sea in the northern portion of Monmouth County, and again at Cape May; but in the long interval the sea breaks upon a succession of low sandy beaches. Between these long narrow islands, and the mainland, which is commonly called "The Shore," are salt meadows extending for miles, yet broken and interrupted by bays and thoroughfares. More than 155,000 acres of salt marsh are distributed along the coast from Sandy Hook to the point of Cape May, including also the marshes on the Delaware Bay side of that county. As of old, so now, they furnish good natural pastures for cattle and sheep all the year round, and are highly esteemed by the farmers whose lands border on them, as they constitute also an unfailing source of hay for winter use and a surplus of exportation. [2]

Farmers along the Delaware Bay accessed the salt hay meadows easily because shore lines were protected from tidal inundations by mud banks or dikes. Reclamation allowed the hay to be cut year-round. Along the Atlantic Coast, however, the marshes were never reclaimed and farmers waited for extremely low tides or for the meadows to freeze before attempting to cut the hay. Art Handson, who continues to harvest hay along the Atlantic Coast, explained:

We start in January when its frozen and then in March and April before the spring rains we duck out and harvest pretty decently. Of course, the thing to do is to go as fast as you can and have things ready and just pull in off the meadow and unload whenever you get a chance. Just get it in. I've worked snow. In the winter time you don't have to worry so much about drying. [3]

In addition to using nature to provide appropriate harvest times, farmers in the shore areas dug drainage ditches to eliminate mosquito-breeding places and increase the marsh's productive power by allowing better grades of salt hay such as black grass to grow. D. M. Nesbit in his report, Tide Marshes of the United States, gave reasons why reclamation projects were not as successful along the Atlantic Coast.

In the northern part they [the marshes] are exposed to such storm tides as will for a long time preclude general reclamation. Farther south they are protected by sand beaches, which are separated by bays and lagoons from the mainland. Here the tidal action is generally small, and more or less the drainage of water must be lifted by machinery if they are reclaimed. [4]

Today only a handful of farmers along the Delaware Bay and several along the Atlantic Coast take advantage of this natural crop. The modern techniques used to harvest the hay, as well as the farmers' memories of past procedures, add an interesting chapter to New Jersey's agricultural history.

Salt Hay Farmers — Then and Now

Despite mechanization, many of the principles behind the modern harvest of salt hay are the same as they were during the colonial period. In some instances, the principles have been handed down to members of each generation. In the case of Ed and Lehma Gibson, salt-hay farmers in Port Norris, the business was passed to them by Lehma's father, Austin Berry, who inherited it from his father, Leaming Berry. Salt-hay cutting has been in the Campbell family for several generations: George Campbell of Eldora inherited his meadows from his father, Stewart Campbell. Both the Gibsons and Campbell cut several thousand acres a year. Today, other Delaware Bay commercial farmers include Clarence Berry and his son, Dean, of Port Norris; Franklin Garrison of Dividing Creek; Michael Coombs, Preston Durham and Wayne Durham of Fairton; Marshall Hand of Goshen; and Ezra Cox of Heislerville. Most hay is harvested from marshes directly on the Delaware Bay and its tributaries, the Cohansey River, Sluice Creek, East Creek, and Goshen Creek.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, salt-hay farmers along the Delaware Bay included Frank P. Sowers and Samuel S. Powell of Salem; John Pancoast Sr., Hancock's Bridge; John P. Shimp Sr., Samuel K. Shimp, and John Shimp, Woodstown; Jack H. Wheeler and Wilmer Ludlam, Goshen; and Alvin Hand, Eldora. These men cut along the Delaware Bay, Cohansey River, Sluice Creek, and Goshen Creek, as well as Salem River, Maurice River, Alloways Creek, Hope Creek, Cedar Creek, Florida Creek, Dividing Creek, and West Creek. [5]

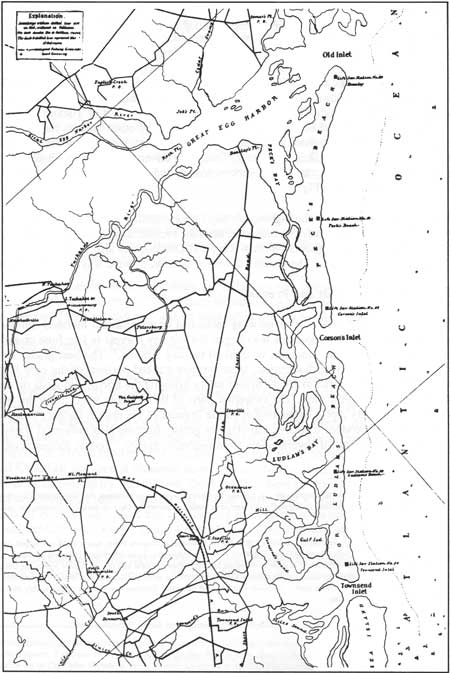

The prominent Atlantic coast salt-hay farmers of this period included Frank Carter, Bertram Carter, Elton Carter, Sadoc Estlow, the Cranmer family, the Jablonsik Brothers of Barnegat, Edwin Sooy of Weekstown, the Farrington family of Cheesequake; Charles Mott of Tuckerton; Issac Steelman of Northfield; and Jay Lee of English Creek. [6] These and other farmers harvested the marshes along such coastal bays, rivers and creeks as Barnegat Bay, Egg Harbor Bay, Mullica River, Forked River, Tuckerton River, Little Egg River, Great Egg River, Goose Creek, and English Creek. Smaller tributaries of these rivers, as well as various sounds and inlets, also contained marsh meadows that produced salt hay (Fig. 24). [7]

Currently, Art Handson is the biggest salt-hay farmer, cutting only several hundred acres along the Atlantic Coast. He obtains his hay from marshes located along English Creek, a tributary of the Great Egg River. His neighbors Norman King and Don Nickles also dabble in the business when time and conditions permit. These men cut only a fraction of what was once harvested. [8]

Salt Hay Harvest — Past and Present

Today, salt hay farmers—whether mowing reclaimed or unreclaimed marshes—follow the tradition of their parents and grandparents who began the salt hay harvest in late June or early July and continued well into the winter months, or until all the hay was cut. [9] The best grades were cut before the first frost. Prior to mechanization, some farmers stacked portions of the crop in the meadow and waited for the marsh to freeze before safely bringing the horses and sleds or wagons out onto the meadow to retrieve the hay. The swampier parts of the meadow were cut in the winter time, too. In late March or early April, depending upon the dryness of the marsh, farmers burned the meadows, which helped produce a clearer and brighter grass. Burning also prevented tracts of meadow that had not been cut for several years from becoming boggy. Today, farmers rarely burn the meadow, but it is still considered a means of producing a better crop and controlling the growth of phragmites, a worthless marsh plant that chokes out the salt hay. [10]

In addition to burning the meadow grasses, farmers along the Delaware Bay opened sluice gates during the spring to allow the tide to come onto the meadow; the tidal waters infused the salt hay with salt and nutrients. When June came they closed the sluice boxes. This procedure is still common to some extent when the weather is very hot and dry. Farmers caution, however, that water left on the meadow too long will scorch the hay. [11]

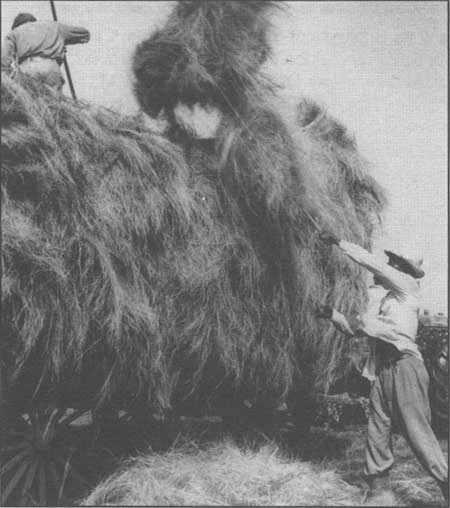

Although the technology involved in salt-hay farming has changed over the centuries, one factor remains constant: it is a labor-intensive effort that requires teamwork and cooperation. Until the 1920s, most of the work done on a salt-hay meadow was by hand and horses, including the cutting, loading, and baling processes (Fig. 25). Local farmers worked together to harvest the hay and share the work. Campbell recalled that during the winter the smaller farmers would help his father, Stewart Campbell, harvest hay while in the summer months unemployed oyster shuckers replaced the farmers. His father always hired eight to ten men during the harvest season. Campbell explained:

In the summer we hired blacks from Port Norris who shucked the other time and then in the winter we hired small local farmers. In the spring the blacks went back up the bay and the farmers back to their farms and this was our slow season anyway. When the oyster business died the blacks went into the factories and we lost our help. [12]

|

| Figure 25. Until the 1950s, salt hay was loaded onto wagons via pitchfork. Gibson's Private Collection. |

Once cut, farmers put the hay into piles over two parallel poles that could be picked up by two men and carried to a haystack or scow. If left at the edge of the meadow, workers piled the hay so the outer layers acted like a thatched roof and protected the inner mass from rain or snow. [13]

Campbell further explained the way he and his father stored the hay: "We would bring the hay out of the meadow all summer and put it in big stacks (bents) put one up and then move and put another one up until you got eight or ten and then you called that a stack," he said. "There was always a fire space between the stacks." [14]

Henry Hayes, a resident of Port Norris and an employee of Stewart and George Campbell as well as Leaming and Austin Berry, added to Campbell's description of the harvesting process. [15] Hayes explained that harvesting salt hay was a twelve-hour-a-day job that started at 6 A.M. and ended at 6 P.M.; his first employers paid him $1 a day with a bonus at Christmas. Hayes's season with the salt-hay farmers began in the middle of June and lasted into October, when he went to work in the shucking houses or on an oyster boat. If the bay froze and the oyster schooners could not get out, he returned to help whichever salt-hay farmer had a job for him.

Preparing the horses for work marked the beginning of Hayes's day. At the meadow they either pulled mowing machines or wagons; at the time, the mower was the only piece of machinery used in the field. The hardest part of working with horses, according to Hayes, was making sure the meadow had a "good bottom," or was solid ground.

It would be about eighteen head of us out there doing that sort of work and the main thing was finding good bottom to keep the horses up because a lot of the bottom you could not walk across at that time. It wasn't ditched off like it is now. They had a little old piece of road down there and use horses. They didn't have to have nothing heavy on it and built it out of mud. They took the mud out of the ditch, piled it on it and then they put a little sand on it. A lot of times they put poles under the mud for support. [16]

Horses wore special footwear: wood, leather, or iron mud-boots strapped or buckled to their hoofs that kept them from sinking (Fig. 26).

These mud-boots—serving in the manner of snow shoes—were made in various forms and with different methods of attachment. Three or four layers of heavy sole leather, copper riveted, were cut to fit the iron shoes already on the horse and had uppers that came up on the front and sides of a hoof. Heavy straps and buckles held the boot on the foot. Similar boots and rounded wooden ones with leather uppers were used on the meadows near Hancock's Bridge. [17]

|

| Figure 26. Shoes such as these were worn by horses that worked on the meadows. Early Industries. |

Some horses wore regular horse shoes with an iron loop on the side that bent slightly upward so as not to interfere with their step. Oxen, wearing half a regular shoe, also worked the meadows. [18]

Unfortunately for the horses, sinking into the marsh was only one problem. Greenhead flies and mosquitoes constantly molested the animals. George Campbell said:

I used to feel sorry for the horses in the summer, for I saw blood run down their legs from greenheads and mosquitoes. We had leather straps with a series of many strings hanging from them so when the horse shivered his skin it would brush off the flies and mosquitoes. We would also tie burlap bags under their bellies saturated with pine tar. If the bugs were real bad we would take burlap bags, make hoods with just their nose and eyes cut out. Sores were treated with pine tar. [19]

Barring any problems with the horses, each man continued with his assigned duty; pitching the hay on a wagon after it had been cut, raking it into windrows for drying, and raking it again into bunches. Horses provided the power and movement for all implements until the 1930s. [20]

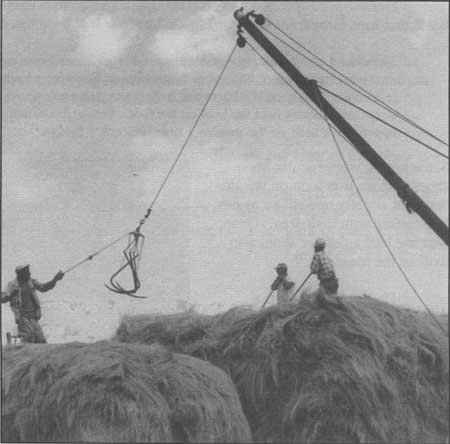

Three to four men worked on a wagon, one in it while the other three pitched up the hay. The horses then pulled the wagons upland where the hay was stacked. By the 1930s, hay was no longer stacked by hand, as described by Betsy Woodman. Instead, farmers employed several types of mechanical stackers, including a swing boom attached to a mast guided by ropes or cables; a derrick with a revolving center mast with a boom attached; a tilting mast supported by guy ropes, but mobile enough to swing alternately over a load of hay and a stack; and a carrier running on a cable supported by masts (Fig. 27). [21]

|

| Figure 27. Hay was unloaded from wagons via a swingboom and grapple hook. Gibson's Private Collection. |

While working for Stewart Campbell, Hayes recalled using a swinging-boom stacker to unload the hay from hay or oyster scows and load it onto a truck. He and the others took hay-filled wagons to the meadow banks and loaded it on to oyster scows located on Slaughter Creek. A yawl boat then towed the scow up to the Dividing Creek Bridge where there was a swing boom made from a telephone pole. The boom, which had a grapple fork at the end, swung over the creek and lifted the hay; the boom would swing back with the hay and deposit it on to a truck. The Berry operation used similar equipment. [22]

Some hay scows, or gundalows, are described in New Jersey historical accounts. Most were made of 2" wide white cedar planks nailed together with 4-1/2" square-cut nails; the bottoms were made of Jersey pitch pine. Others were described as being 33' long, 12' wide, and 3' high from deck to bottom. Many hay scows were still in operation in the 1930s. Before motorization, the scows were pushed by two men on board using 15' cedar poles, or were towed up the creek by one man walking along the bank and the other following with a pole to keep the craft from running ashore. Yawl boats were used once the process was mechanized, though by 1950 most had disappeared. [23]

Hayes also remembered loading hay onto scows at Florida and Ware creeks. He disliked this method of transportation because it required leaving the bayside around 4 P.M. and not arriving to the Dividing Creek Bridge until 11 P.M. Removing hay from the meadow by wagon, to trucks, then to railroad cars in Port Norris or Dividing Creek took less time; Leaming and Austin Berry often used this method.

Similarly, Charlie Weber, one of the last traditional salt-hay farmers along the Atlantic coast, used hay scows to transport himself and his horses to and from the meadows along the Mullica and Wading rivers. Well into the 1940s, Weber mowed many of his own acres as well as those he rented. In an interview with Henry Charlton Beck, Weber commented:

I use to mow hundreds of acres. Once on the medders there'd be places with a mile long to mow. It took a good pair of horses to make a round in forty-five minutes. I used to cut from the mouth of the river to Goose Creek Cove—they wasn't always my own medders, you know. I rented some of them. They used to be bid off at auction sales. Many of the renters never paid. But I paid—and sometimes I got them all. [24]

Weber also relied upon horses and horse-drawn machinery to harvest his hay. The only modernization he adopted was his son's clamming garvey in the mid 1940s, and this was only used because his sons, Charlie Jr. and Ed, were helping him. Beck best described Weber:

First sight of Charlie's barge coming up the river makes you wonder what it is. Chances are you would never see it going down empty, for that voyage down the Mullica around the bend and up the Wading River is made very early in the morning, long before the first streak of dawn. At first you would see only what would appear to be a heaped-up, squarish stack of hay, surrounded by water and moving steadily nearer. Not until much later would you make out the garvey and hear the drone of the six-cylinder Dodge engine Charlie, Jr., installed years ago. [25]

Unlike the salt hay farmers along the Delaware Bay, Weber used his barge and his son's garvey out of necessity. He could not access the meadows or transport his loose hay by any other means. Small creeks interrupted many of the marshes, making a straight path over them impossible. In some cases, farmers built bridges over streams and laid corduroy roads, which were logs placed on the meadow side by side and perpendicular to the watercourses. [26]

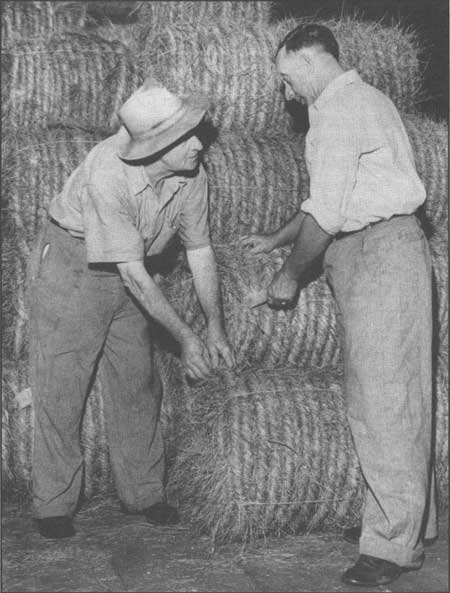

Not all hay was shipped loose like that mowed by Charlie Weber or handled by Henry Hayes. Stationary balers, or bale presses, compressed the loose hay into a firm unit. LaDonna Gibson Angelo, granddaughter of Austin Berry, described the process of using a stationary baler. The balers operated off a tractor-powered belt. The workers deposited enough hay to form two bales, they inserted a dividing board into the baler and wrapped wire around the bales. Hayes also used stationary balers, though his were powered by a locally made Hettinger engine that was popularly used to power oyster dredges. [27]

Once the bales were made, workers weighed and tagged them. Lehma Gibson described how her mother would take the tags off the bales as they were loaded on a truck en route to market, adding them up to determine the cost of each load of salt hay.

By the late 1940s, tractors had replaced horses except where the ground was extremely soft. Campbell described it as a "big event in our lives" when he bought his first International F-12 with steel wheels. The Farmall A tractor replaced most of Stewart Campbell's horses because it was light enough to stay suspended on most meadows. By the 1940s, Austin Berry was fitting his tractors with dual rear wheels to keep them from sinking (Fig. 28).

|

| Figure 28. Austin Berry raking salt hay in the 1940s. Notice the dual rear tires on the tractor. Gibson's Private Collection. |

Campbell and Berry, however, used wagons with wood wheels until the 1950s. Some wheels had an extended rim, measuring 6" wide so as not to sink. The transformation to tires in the 1950s, along with a decrease in the weight of automatic balers, allowed the Berrys and Campbells to fully mechanize their operations (Fig. 29). Berry's son-in-law, Edward Gibson, modified much of his machinery by building sled runners or skids under the body to prevent them from sinking (Fig. 30). [28]

|

| Figure 29. During the 1950s, balers were introduced to the salt-hay industry. Gibson's Private Collection. |

|

| Figure 30. Skids are placed underneath of modern equipment to prevent them from sinking below their axles if a soft spot is encountered. Sebold. |

Today, Gibson and Campbell use a variety of upland equipment, including tractors, propelled mowers (that mow and rake simultaneously), hay balers, and wagons with automatic loaders (Fig. 31). The farmers build supporting skids on all of the upland equipment with the exception of tractors with dual wheels and flotation tires. Moreover, Gibson now loads his hay with a fork lift onto tractor-trailers to be taken to the buyers.

|

| Figure 31. Chris Angelo, the Gibson's grandson, drives an automatic bale wagon on the marsh to collect the bales of hay. Sebold. |

The invention of new types of heavy machinery to dig ditches and build banks brought changes to the salt-hay industry, as well. Currently, farmers employ cranes to keep the ditches cleared and the banks reinforced. Landowners also construct more reliable roads through the meadows to support the heavy cranes. When working along the bank, the operator drives the crane atop wood mats that keep it from sinking into the soft marsh. This way, farmers have increased the number of ditches within their salt meadows, and the meadows are drier and capable of supporting heavier machinery. Hayes commented several times how he knew of various meadows where at one time men and horses could not safely walk, but now they are so dry that trucks and tractors can drive across them without worry. [29]

Prior to cranes, muddiggers operated dredging machines that dug ditches and built up the banks; these machines consisted of a barge equipped with a crane that had a clam scoop on the end. In the Salem area, large machines worked for months at a time repairing the banks along Salem Creek. Some of the smaller dredging machines were powered by steam or gasoline engines. William K. Harris and his brother Lewis, of Harmersville, operated a small dredging machine. William built the gasoline-powered device in his basement, then placed it on a scow. When the dredge could not float it was moved by rollers along planks. The brothers gained nicknames for their roles: "Greasy Bill" was the engineer and "Muddy Lew" operated the bucket. William eventually sold the operation to his brother who continued working until 1940. [30]

George Harbeson, another Salem County resident, inherited a small steam-powered dredging machine from his father. Harbeson modified it several times, including the replacement of an upright boiler with a second-hand horizontal locomotive boiler. He used it primarily in Salem County, although Harbeson occasionally traveled to Maryland, too. In 1964, when working in Elsinboro on Money Island Ditch, the dredge was vandalized so severely that it was no longer operational. [31]

Muddiggers and their machines also operated in Cumberland County. Ed and Lehma Gibson, as well as Janice and Jeanette Burcham, had on separate occasions hired a dredging operation that worked out of the Del Bay Shipyard in Leesburg. The Gibsons referred to the dredge operator as "Muddigger Lou," whose dredging machine sank in the Delaware Bay several years ago and was never recovered. [32]

Problems Encountered by Salt Hay Farmers

The control of phragmites communis is the biggest problem that salt hay farmers face today. Phragmites, a common marsh grass, can grow between 4" and 13' tall but it has no value. The grass adapts to all conditions, even marshes with high salinity or that have been treated with herbicides. In the latter, phragmites is the first species to return. The grass has a complex root system that is difficult to kill; moreover, new plants take root when the mother plant is broken off. Today, phragmites not only kills the vista of the meadows, which at one time were unbroken, but also the meadow grass itself. [33]

Age-old problems such as muskrats, fiddler crabs, horseshoe crabs, and storms continue to disrupt salt-hay farming today, because they harm the protective banks that keep tidewaters off the meadow. Muskrats and fiddler crabs burrow into the banks, for instance, and cause breaches. Hayes commented on his experience repairing the banks.

A lot of time, the muskrats dug it out [the bank] and undermined it. We had to go down when the tide came through and dig the muskrat hole out and put the dirt back in. A lot of times we'd put chicken wire in the holes. The muskrat would come back and wouldn't be able to dig through. [34]

Along the Atlantic coast farmers watched for muskrat holes, which could cause a horse to break a leg if the animal stepped into it.

Fiddler crabs and horseshoe crabs also undermine the support system of the man-made banks by cutting away at natural stream banks. As the banks erode, the creeks widen, making it harder for salt-hay farmers to get across. Campbell described such a problem at Dennis Creek.

When I first came down here we went across and hayed down toward Dennis. At that time I put telephone poles across it and made a bridge, but today the creek has widened and I cannot get across. What has done a lot of it is the king crabs. They crawl along. . . claw and cave the banks, widening our creeks out. It's phenomenal. Muskrats also do a number, but all along here the crabs are caving the creeks in. West Creek is three times as wide as it was when I first came here. It's not any deeper. It's getting shallower because the water fans out. It's tremendous what they do. [35]

Horseshoe crabs also plague the farm equipment. When the banks break or the sluice gates are open, the crabs float into the meadow by the thousands and die there. After the water recedes, the crabs begin to decompose, creating a noxious smell as well as a hazard to the equipment. The shells can pierce tires or jam a hay baler. Farmers simply avoid those areas of the meadows where the crabs accumulate. [36]

Farmers along the Atlantic coast experienced some problems not common along the Delaware Bay. Access to hay growing on marshes that were not reclaimed was limited, thus restricting farmers to those areas which were not frequently flooded and were at higher elevations. Additionally, the development of the shoreline into beach resorts hurt salt-hay farmers. As more people became aware of the recreational facilities offered at these resorts, railroads and turnpikes that connected the mainland with the shore brought changes to the meadows; sections were filled in and numerous drainage ditches were dug. In turn, the marsh environment, which was so dependent upon the height of the water table and the salinity of the soil, changed in composition. [37]

Salt-Hay Use

Salt hay has been ingeniously adapted to local needs. At one time it served as stable bedding for horses and cattle, fodder for cattle, thatch for barn roofs, mulch for strawberry plants, packing for glassware and pottery, insulation for icehouses, traction on roads, as an ingredient in wrapping and butcher's paper, and for protecting newly poured concrete and pavement roads during the winter. During World War II, the government bought large quantities of salt hay to be used in the construction of airport runways and concrete roads. At times it was also used to cover swimming pools during the winter. [38]

Today, most salt hay is shipped to buyers in New England, Pennsylvania, and northern New Jersey for use at nurseries, in road construction, and as septic-tank insulation. Nurserymen favor it as a mulch because the seeds cannot adapt to upland conditions, making it virtually weedless.

Hay was also used, and still is to a lesser extent, to make salt-hay rope which, like the harvest of salt hay in general, has become a South Jersey tradition. Owen "Jack" Carney, Jr., a Port Norris resident, learned to make salt-hay rope from his father who established a rope factory in Port Norris in 1907 for a Philadelphia iron-foundry supply firm (Fig. 32). Located on Memorial Avenue next to the baseball field, there were always thirty-five or forty stacks of hay outside of the factory awaiting processing. The building included both a storage area for finished rope as well as the work area.

|

| Figure 32. This salt-hay rope factory, operated by Owen J. Carney, Sr., was located on Memorial Avenue in Port Norris, New Jersey. Photograph 1963, Riggs' Private Collection. |

Carney's father managed approximately ten men; three made the rope, one hauled the hay from the Berry's salt-hay meadows, and the others brought the hay inside and shook it out for the rope makers. Most of the rope was used to help form cast-iron pipe. The hay rope, about 1" thick, was wrapped around the iron pipe mold or core bar, then covered with a mixture of clay and molasses; the rope and clay mixture that formed the inside of the pipe was placed in an oven to harden. Afterward, the core and mold (the outside of the pipe) were placed vertically into a casting pit, and molten iron was poured into it. When the hot iron hit the clay-and-hay mixture, the hay disintegrated while succeeding in keeping the mold, clay, and iron from becoming one mass. The core bar and mold were then removed and the clay knocked loose from the interior with hammers (Fig. 33). [39]

|

| Figure 33. Owen J. Carney, Sr. (left) and Austin Berry (right) discuss Carney's spools of salt-hay rope. Gibson's Private Collection. |

By 1930 newer methods of spinning molds by centrifugal force replaced the need for salt-hay core rope. However, the rope factory remained in business to supply the Philadelphia firm with hay for special castings. The hay let castings vent properly so bubbles, caused by escaping gases, would not form. The Port Norris Rope Factory continued to operate until the 1960s when Carney's brother Gilbert died. Carney moved several of the rope-spinning machines, which work much like a spinning wheel, to a shed in his backyard where he continued making rope in his spare time. [40]

Today, Carney continues to provide rope to Canadian Foundry Supply Ltd. and the Johnstown Corporation. It takes approximately one hour to spin a 450' spool of rope 1" in diameter. The diameter of the rope depends on how much hay he feeds to the machine and how fast the machine is spinning. Smaller diameter rope requires finer hay and a quicker pace; the speed is controlled by a belt-driven, step pulley powered by a five-horsepower electric motor that turns the 500-pound machine. Carney buys his hay loose from the Gibsons because the baling process breaks the hay. It is also harder to separate the hay strands by their size and width after being baled. To ensure that Carney gets the longest and most desirable hay, he marks off his lot of hay with red flags. He then takes his wagon—made of boards from the Atlantic City boardwalk—and loads it. When making his selection, he looks for long, soft, clean hay of which the best is usually near the drainage ditches. [41]

During the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries, salt hay was not the only crop grown on reclaimed land. Many farmers planted regular upland crops. These growers, however, risked the fields being inundated by salty or brackish water, which killed the upland crops and damage salt hay. As a result, some farmers worked together and formed meadow companies, to ensure that the banks remained intact for successful harvest of crops—whether salt hay, clover, corn, or potatoes. With time and changing technology however, these traditions are dwindling.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

new-jersey/marsh-farm/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 31-Jan-2005