|

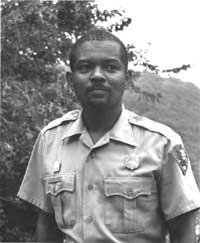

National Park Service

Badges and Uniform Ornamentation of the National Park Service |

|

ORNAMENTATION

Arrowhead Patch

For years there had been agitation within the Park Service for some emblem that would identify the Service as the shield did the Forest Service. A contest was held in 1949 because it was thought at that time that the only emblem used by the Service, the Sequoia cone, did not adequately symbolize the bureau. The winner of the contest, Dudley Bayliss, collected the fifty dollar prize, but his "road badge" design was never used. Conrad L. Wirth, then in the Newton B. Drury directorate, served on the review committee that made the winning selection. He thought that Bayliss' design was "good and well presented, but it was, as were most of the submissions, a formal modern type." They had expected something that would have symbolized what the parks were all about. [28] Shortly after the contest was over, Aubrey V. Neasham, a historian in the Region IV (now Western Region) Engineering Division in San Francisco, in a letter to Director Drury, suggested that the Service should have an emblem depicting its primary function "like an arrowhead, or a tree or a buffalo." [29] With the letter Neasham submitted a rough sketch of a design incorporating an elongated arrowhead and a pine tree. Drury thought the design had "the important merit of simplicity" and was "adequate so far as the symbolism is concerned." [30] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

When Wirth became director in 1951, he turned Neasham's design over to Herbert Maier, then assistant director of Region IV. Maier's staff, including Sanford "Red" Hill, Cecil J. Doty, and Walter Rivers, were all involved in the design process and ultimately came up with the arrowhead design in use today. [31] The arrowhead was authorized as the official National Park Service emblem by the Secretary of the Interior on July 20, 195l. While not spelled out in official documents, the elements of the emblem symbolized the major facets of the national park system, or as Wirth put it, "what the parks were all about." The Sequoia tree and bison represented vegetation and wildlife, the mountains and water represented scenic and recreational values, and the arrowhead represented historical and archeological values. [32] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Starting in 1952, the arrowhead began to be used on the cover of park information folders with the first probably the one published in April of that year for Oregon Caves National Monument. It soon gained public recognition as the Service symbol and became widely used on signs and publications. Instructions for its use on signs were first sent to the field on September 25, 1952. [33] Amendment No. 7, July 29, 1952, to the 1947 uniform regulations prescribed the use of the arrowhead as a patch for the uniform. Enough of these patches were sent to each area so that each permanent uniformed employee received three and each seasonal uniformed employee received one. The patch was to be "sewn in the center of the sleeve, with the top of the insignia 2 inches below the shoulder seam, so that the arrowhead will appear perpendicular when the ARM is held in a relaxed position at the side."

|

The patches were extremely unpopular with uniformed employees when first issued, but quickly "grew" on those wearing them. At first there was only one size of patch, 3-3/4" high by 3" wide, but it was soon realized that a reduced version was needed for women. These smaller patches, 2-1/2" x 2", subsequently also made their appearance on hats and the fronts of jackets for both men and women. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

To forestall unseemly commercial uses of the arrowhead design, an official notice, approved March 7, 1962, was published in the Federal Register of March 15, 1962 (27 F.R. 2486), designating it as the official symbol of the National Park Service. [34]

Prior to World War II, the majority of visitors to national parks, especially those out West, came by train. But during the war, visitation dropped off drastically and a number of the parks were used by the military as training grounds or rest areas. During the War, park appropriations had been cut to the bone and ten years after the cessation of hostilities were still a million dollars under that of 1940, even though a number of new parks had been established. The automobile had come into its own and visitation was up three fold. Time and traffic were turning the Nation's parks into a shambles and because of the lack of finding, sanitation was deplorable and the other utilities were taxed to the utmost. This was the park system confronting Wirth when he became director. In 1956 Wirth initiated a ten year program, entitled MISSION 66, to revitalize the parks. This was to be completed for the 50th anniversary of the National Park Service.

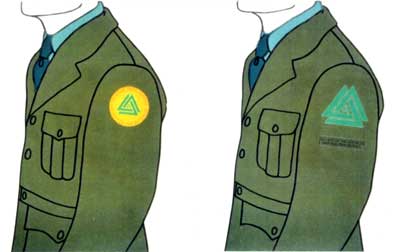

In 1966, to celebrate the Service's birthday, an exhibit entitled PARKSCAPE was erected. This exhibit featured a conservation logo designed by the New York firm of Chermayeff and Geismar Associates consisting of 3 triangles enclosing three balls. The triangles represented the outdoors (trees and Mountains) with the 3 balls being the standard symbol for preservation. In addition, the same firm designed a new seal for the Department of the Interior. Secretary Stewart L. Udall had attempted to change Interior's name to either Department of Natural Resources or Department of Conservation, but this met with great opposition. He did, however, manage to have the seal changed from the buffalo to a stylized pair of hands holding a circle (sun) over two large triangles (mountains) which inturn were over nine small inverted triangles symbolizing water. The hands motif had been suggested by Vince Gleason as an abstract symbolizing that the Nation's natural resources were in good hands. Following closely on the heels of MISSION 66, Director George B. Hartzog, Jr. (1964-1972) came forth with a new agenda titled PARKSCAPE U.S.A. Among it's facets was one that dealt with the upgrading and modernization of the image of the Service itself. Hartzog had become enamored with the logo of the PARKSCAPE exhibit and adopted it for his new program. Hartzog used the occasion of an article in the July, 1966, issue of the National Geographic Society Magazine concerning the National Park System to launch his new program. He assured employees that the triangle symbol would supplement rather than supplant the arrowhead. In 1968, however, when Secretary Udall adopted the new Interior seal (designed by Chermayeff and Geismar Associates), Hartzog seized the opportunity to replace the arrowhead with the Parkscape symbol. With the buffalo gone from the Interior seal, he rationalized, the arrowhead with its buffalo was no longer relevant. Field reaction to this move was nevertheless unenthusiastic, for the representational arrowhead was far better liked than the abstract Parkscape symbol. Nevertheless, boards were made up by Chermayeff & Geismar showing how the new symbols would look on the various pieces of clothing, as well as on vehicles and signs.

On March 3, 1969, Acting Director Edward Hummel sent a memorandum to all regional directors ordering the removal of the arrowhead shoulder patch. "In keeping with the Director's desire to act positively on field suggestions, it has been decided that effective June 1, 1969, Service emblem shoulder and cap patches will not be worn on any National Park Service garments," he wrote. Before this unpopular directive could be implemented, Secretary Hickel reinstated the buffalo seal. Hartzog thereupon reinstated the arrowhead as the official NPS emblem and continued its use as a patch in a memorandum dated May 15, 1969. Perhaps as a gesture to the few supporters of the Parkscape symbol, he simultaneously ordered its retention as the official NPS tie tack. Since then the arrowhead has continued to be worn on the uniform and to enjoy strong acceptance among Service employees. [35] The first patches were filly stitched, creating a 2-dimensional appearance. They were embroidered on a non-sanforized material and consequently could only be used on coats. Subsequent orders corrected this problem. As new orders were placed over the years, the patch slowly evolved into a solid stitched, self edged patch with heavy top stitching, where the various elements were layered onto the field, giving an almost 3-dimensional effect. This, in turn, has given way to the various elements being layered directly onto the base material, thus substantially reducing the cost. This is the arrowhead most often seen today. Lion Brothers, Baltimore, Maryland, have been involved with the development and manufacture of most, it not all of the arrowhead patches made for the Service. It is beyond the scope of this study to show an example of every Arrowhead patch ever made. The following sampling is only meant as a representational illustration of the developmental progression of todays Arrowhead patch.

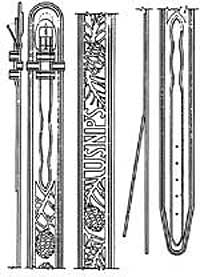

Possibly because the coat was usually worn buttoned up with the uniform, belts do not appear as an article covered by the regulations until 1936. Earlier photographs confirm the prior absence of any standard belt or buckle. Probably the only thing covering belts was the stipulation that all leather would be cordovan color.

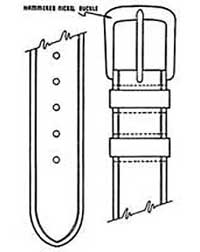

In Office Order No 324, National Park Service Uniform Regulations, April 13, 1936, a web belt was stipulated. In 1938, Office Order No. 350 added a leather belt. The order states:

Apparently the original order did not contain the above description of the leather belt, because on November 10, 1938, Office Order 350 was amended to include a description and a sketch of the leather belt. The drawing shows a plain belt with a line tooled all around, approximately 1/8-inch from the edge. It has two retaining loops, or cinches, for the end of the belt. The buckle was a simple open-frame, single-loop style. The web belt probably utilized the standard military type of slip-lock buckle. Office Order 350 was again revised on April 19, 1939. This time the web waist belt was eliminated and the color of the leather belt changed to the standard cordovan color of Park Service leather goods. The width was also increased to 1-1/2 inches. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The 1940 uniform regulations brought with them two additional optional belts. Besides the standard belt, ranger could now wear a 1/8-inch-thick by 1-1/2-inch-wide belt embossed with a design similar to the hat band. This belt was of the "billeted" or "western gun holster" style, which has a secondary narrow belt sewn on top of the wider main belt. The narrow belt was used to secure the larger one. In addition, Service employees required to wear side arms could wear a belt with a strap over the shoulder to support the weight of the weapon if they desired. This style belt, known as a Sam Browne, was copied from the British military and used by the U.S. Army as well as law enforcement agencies. Both of these belts were to be cordovan. The 1961 uniform regulations changed the embossed belt. It remained 1-1/2 inches wide, but now the buckle was the full width of the belt and the "USNPS" was eliminated. This became the standard belt for the National Park Service and continues to this day.

A number of NPS buckles have been suggested or made over the years, but they are all unofficial and usually not allowed to be worn with the uniform.

U.S. Army buttons were doubtless used occasionally by rangers prior to the introduction of civilian uniforms. The first button known to have been used by a ranger on a uniform in the Interior Department's "park service" is the 1907 Forest Service button. This button shows up in a photograph of Karl Keller, a ranger in Sequoia National Park, taken in 1910. It has a pine tree in the center, with the words Forest on top and Service underneath. In 1911 the first uniforms were officially authorized, sanctioned would be a better word, for use by rangers in the park service. These uniforms were purchased from Parker, Bridget & Company of Washington, D.C. [36] The matter of special park service buttons was broached, but the department concluded that: "inasmuch as we would have to have a die made for the special buttons for the park service which would cost about $28, we had best drop the matter of the special buttons until the future of the national park service is definitely determined. If the Bureau of National Parks is created, another design of button might be necessary. The uniforms are now equipped with United States Army buttons." [38] That winter, Sigmund Eisner of Red Bank, New Jersey, began negotiating with the department to furnish new uniforms for the park rangers. In his correspondence. he offered to have "buttons made to any design for the service for which they are intended. I would keep these buttons in stock subject to your orders." [39] At a subsequent meeting with Chief Clerk Clement Ucker in Washington in December or early January 1912, Eisner was apparently shown one of the park service badges as a possible pattern for the new buttons. [39] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Soon after the interview, Assistant Secretary Arno Thompsom wrote Eisner requesting drawings of the proposed uniforms, together with "advice as to whether bronze buttons bearing the eagle design surrounded by the words "National Park Service, Department of the Interior," as used upon the park ranger service badge shown you, will be purchased and placed upon the uniforms." Eisner agreed to this and stated that he would "have die made for these buttons in all sizes."badges as a possible pattern for the new buttons. [40] Subsequently, not only were these buttons used on the uniforms made by Eisner, but the department also purchased them for uniforms the rangers had made by other manufacturers and to replace those lost through attrition. Even though the rangers had to furnish their own uniforms, the buttons were given without charge.

These buttons were stocked and sold to the department by Eisner. The early buttons were made by the Waterbury Button Company of Waterbury, Connecticut, but were back-stamped SIGMUND EISNER/RED BANK, N.J. Later buttons carry the Waterbury back stamp. As stated above, they were modeled after the 1906 badge and were finished in what was classified as a "bronze" finish. This appears to be a sort of heavy coating. This coating was the subject of much controversy in later years because of its chipping and flaking. The 1926 Uniform Committee (to report at the 1927 meeting) voted four to two to change the uniform coat buttons from bronze to gilt. They believed that gilt buttons would set off the forestry-colored cloth to a greater advantage and added "distinctiveness and snappiness" to the uniform. This recommendation was included in the proposed changes for the new uniform regulations. Upon reviewing the committee's suggested regulation changes, Horace Albright, then Yellowstone superintendent and assistant director (field), found several of the proposed revisions "particularly objectionable." Among them was the change to gilt buttons. He recommended that the current regulations be continued in force for 1927 and that the revisions be submitted to the superintendents for their comments. [45] Albright must have done his work well, for nothing else was heard of "gilt" buttons. Complaints were still being heard about the lacquered finish on the buttons flaking and coming off. In the mid-1930s Waterbury started using an "acid treated" process. This insured that the button was clean and the resulting chemical coloring was bonded securely to the metal, obviating the use of heavy lacquers. This process is still used on the National Park Service buttons today. [46]

Walter Fry, the ranger in charge at Sequoia National Park, has long been credited with suggesting that the "National Park Service" badge be used as the model for this button. This may or may not be partially correct. In a letter he wrote to the Secretary of the Interior requesting authority to purchase "Forestry green winter uniforms." he also requested that they be "equipped with the bronze Army buttons, bearing design of eagle, same as our badges now worn, instead of the Forest Service button." [41] The rangers at Sequoia National Park had worn the forest green uniform with Forest Service buttons since 1909, and Fry probably only wanted the new uniforms to have "bronze Army buttons" like the new uniforms then being made. It is possible that his statement "bearing design of eagle, same a sour badges now worn" may have influenced the department when they considered a design for the new buttons, but there is no documentation to substantiate this. In a letter dated May 14, 1915, Mark Daniels, general superintendent of national parks (a position roughly equivalent to the later director), proposed that a "bright" button replace the "bronze" buttons then being used on the service uniforms. [42] He included a sample button with his request, which the department forwarded to Sigmund Eisner, requesting prices. Eisner responded with prices of $5.00 and $2.50 per gross for large and small buttons respectively, whereupon the department ordered a gross of each. [43] Delivery lagged for months, with the department requesting the buttons, and Eisner promising them any day, until finally in October he wrote the secretary that he was unable to make the manufacturer (Waterbury) understand what was requested and needed another sample. [44] This request was forwarded to Daniels, but the records are mute as to the disposition of the matter. There is no evidence that these buttons were ever made. Almost all 2-piece buttons of this type are made of brass and "bright" was a trade term meaning polished brass with a lacquer finish. There is a brass button in the NPS History Collection that was never plated, but it is without provenance.

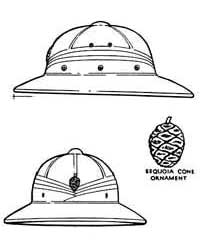

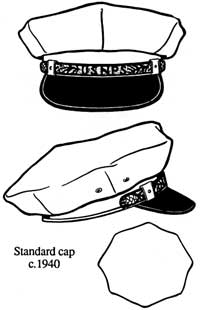

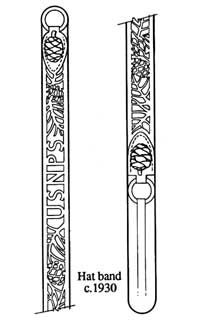

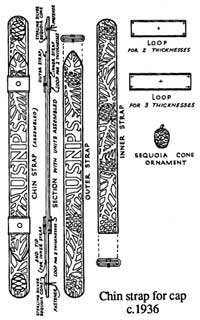

Wearing the standard hat was inconvenient for those rangers assigned to motorcycle duty. So the soft, or "English" army officer, cap was authorized in 1928 for rangers assigned to that function. This was expanded to include "hot summer" parks in the east. The initial authorization did not include any decoration on the cap, but this was changed by Office Order No. 204, revised, in 1932. This order specified that a "modified form of the National Park Service band" was to be worn with the cap. This consisted of a chin strap, with some of the same elements found on the hat band impressed on it. It also had USNPS tooled on the front center. It was held at the sides by two sterling silver Sequoia cones, like those used on the hatband. Although subsequent uniform regulations still specified the cap to be the "English Army Officer" style, the design was changed sometime soon after its introduction to that used by police officers. (faceted rim) Even though no ornament was specified for the front of the cap, photographs show several rangers sporting what looks like a large eagle on the front of their caps. There had been some discussion concerning this back in the late 1920s, when the cap was initially proposed, but the matter of the ornament had been dropped at that time. There are photographs showing Tex Worley, of Yellowstone, wearing his ranger badge on the front of his cap.

The 1938 superintendents' conference had recommended an aluminum-colored pith helmet, with a large sterling silver Sequoia cone ornament. But when Office Order No. 350, revised, was issued on April 19, 1939, the color of the helmet was changed to forestry green and there was no mention of an ornament. This was cleared up in a memorandum from Acting Director Demaray on July 27, 1939. "It was found that aluminum colored helmets could not be purchased and no satisfactory sequoia cone has been devised for use on the helmet," he stated. "Consequently the color of the helmet was changed to forestry green and the core ornament eliminated."

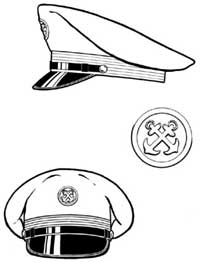

The 1940 uniform regulations changed the color of the helmet again. This time it was to be of a "sand tan color." And apparently, because of availability, the sterling silver Sequoia cone was reinstated, but this time it was to be the same size as those worn on the hatband. On September 18, 1953, the sun helmet was eliminated from the uniform regulations and the Sequoia cone reverted to being used solely on the standard hat and cap. The 1940 regulations also introduced a new uniform for those rangers, or boatmen, that worked on boats of the National Park Service. The wording is somewhat odd. It states, "...the following articles of uniform are prescribed for wear by the boat captain, engineer purser or other employees [italics added] of the boats." This could be construed to mean everyone working the boat, unless of course the hands were simply assigned from the ranger force by the parks. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The uniform was to be Navy blue, including the cap, which was modeled after those worn by Chief Petty Officers in the U.S. Navy. The regulations do not address the issue, but this uniform was probably intended strictly for the Service's deep water "Navy", like the boatmen that crewed RANGER's II and III on Lake Superior for Isle Royale National Park, since this is the only location that apparently received them. The 1947 uniform regulations authorized a summer uniform of white duck. The style and decoration were to be the same. The cap was to have a distinctive ornament on the front. It consisted of an 1-1/2" circle with crossed anchors in the center. All embroidery was to be gold thread on navy-blue cloth. Although the uniform remained in the regulations until 1961, it apparently wasn't too popular since few photographs exist showing it being worn. There are no extant examples known. The 1961 Uniform Regulations changed the Boatmen's dress back to the standard ranger uniform, less badge, including standard hat when ashore. However, when on board the boat, officers were to wear die Chief Petty Officers style cap, only now it was to be forest green. same as the uniform, with the emblem being gold thread. The hands were to wear the standard service cap. A photograph of Charles R. Greenleaf, captain of the Ranger, shows the emblem on his hat to be larger and more ornate than that previously used. It is still the crossed anchors, but mow they are "fouled." Even though the regulations now specify that only the crews out of Isle Royale were to wear the Petty Officer cap, there is a photograph of Gene F. Gatzke from Lake Mead Recreation Area wearing one with this emblem. In addition to the patch, he has what appears to be a small round metal disc with NPS on it fastened at the top between the anchors. Regulations must not have been too strict, later photographs show Greenleaf wearing caps with various emblems on them. Even occasionally the service cap.

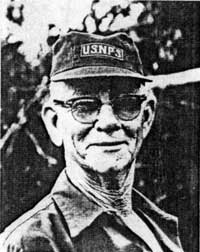

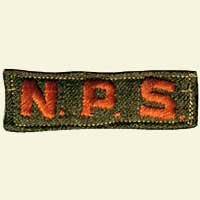

A ski cap was introduced in 1936. [47] This was the first of a series of caps bearing an embroidered USNPS. The letters were to be gold and 3/4-inch high. The 1961 regulations specified that women's "airline stewardess" hats were to have USNPS embroidered on them in 1/2-inch gold letters. The letters were either embroidered directly on the hat or on a piece of material matching the hat. However, prior to these regulations becoming effective, the color was changed to silver to be consistent with the collar insignia and badge. [48] The National Park Service History Collection has an example of the USNPS embroidered on a piece of uniform material for the women's hat. But since it is gold instead of silver, it can be assumed to be a sample made before the color change. Since most of the photographs from this period are black and white, the color cannot be identified. There is, however, a color photograph from Everglades National Park showing 3 women wearing hats with white USNPS on the front which confirms that, at least in their case, white was used in place of gold. The embroidered USNPS on the women's hat was replaced in 1962 by the "reduced" size (2-1/2-inch) arrowhead patch. As in the case of the women's hat, when the new style ski cap, now called a service cap, was adopted in the 1961 regulations, it was specified to have USNPS embroidered on the front, like the previous cap, but this was also changed to silver in 1960. Now, though, the USNPS was embroidered on a piece of the cap material, all on one line, and sewn to the front of the cap. Sometime prior to 1969, at which time it was eliminated in favor of the arrowhead, the USNPS began to be embroidered in 2 lines on a two inch square forestry green patch with a silver (white) border and sewn to the cap. No evidence has uncovered as to when these patches were authorized. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Prior to the adoption of the "stewardess" hat, uniformed women employees had been wearing a uniform copied from the Women's Army AuxilIary Corps (WAAC), complete with overseas cap. Although not covered in the regulations, a USNPS collar ornament was usually attached to the front of this cap. There is photographic evidence that this hat began to be worn during World War II. The small arrowhead patch was officially removed from the women's hat in 1969 but continued to be worn until the uniform change of 1970. At that time, it replaced the USNPS patch on the men's service caps. Since 1974, the arrowhead has seen service on many different types of hats, either as a patch or a decal. It was used on baseball caps, "Black Watch style" (ski) caps, and mouton-trimmed caps, to name a few. When the soft cap worn by the motorcycle patrol rangers gave way to the safer hard helmets, arrowhead decals were affixed to them to denote the wearer's status. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

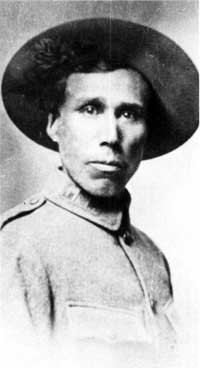

The first documented collar ornament to be worn on the uniform of a park ranger was the US from the collar insignia of Army officers. This shows up in two portraits of rangers in Sequoia National Park circa 1910 and 1912-16. It was easy to obtain and dressed the uniform up to look official. Although the Secretary of the Interior had authorized the use of a uniform in the parks in 1911, nothing was said about distinctive insignia. Consequently, the various parks were left to their own devices. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In 1916, Washington Bartlett "Dusty" Lewis, then supervisor at Yosemite, had Meyer's Military Shop in Washington, D.C., make up several NPS insignia. [49] When Lewis proposed that the National Park Service adopt an ornament for the new 1920 coat, he offered one of these as a possible model. From the correspondence, it would appear that these were simply letters attached to a bar, which could be pinned to the collar. Responding to Lewis, Acting Director Cammerer wrote, "There are a number of serious defects in the design, which is a stock-cut proposition put out in the cheapest possible way for the largest gain." [50] No examples of this ornament have been found, but it shows up in a couple of photographs depicting Yosemite rangers from around 1919. One is of Forrest Townsley, taken while he was on temporary duty at Grand Canyon National Park and the other is of William "Billy" Nelson, from the Ansel Hall Collection. If stock, as Cammerer states, the letters would probably be 1/2". | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

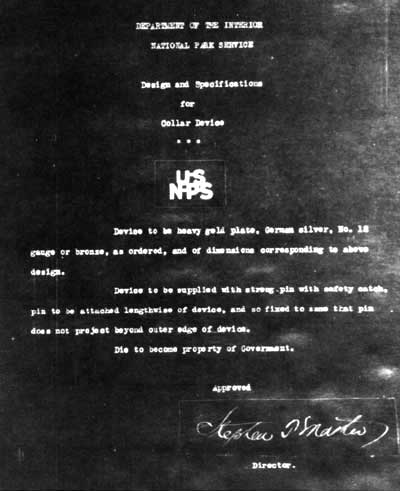

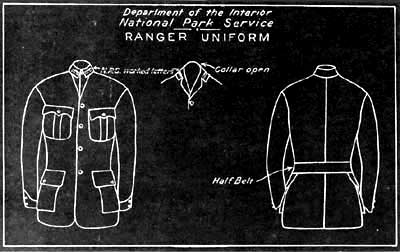

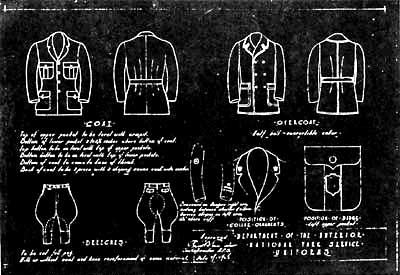

In late 1917 or early 1918, Service headquarters started requiring "N.P.S." to be stitched on the collar of the uniform in bronze thread, "to match the buttons." [51] There is a 1919 forestry green cloth coat in the Yellowstone collection with NPS on the collar. [52] In this case the N.P.S. is embroidered on a piece of coat material and then stitched to the coat collar. The original bronze-colored thread has faded to an orange. This coat would indicate that the NPS was used from it's introduction until the new metal USNPS collar insignia came in with the 1920 regulations. Glacier had earlier requested that G.N.P. be applied to their collars, but this was turned down. The 1920 uniform regulations ushered in what was to become the second oldest insignia still in use by the National Park Service: the USNPS collar ornament. Only the button is older. Building on Lewis's suggestion, the Service finally decided to use the NPS but with US over it. A drawing of the ornament shows that the letters were to be 1/4-inch high and states: "Device to be supplied with strong pin with safety catch, pin to be attached length wise of device. and so fixed to same that pin does not project beyond outer edge of device. Die to become property of Government." Officer's ornaments were to be heavy gold plate. ranger's. No. 12 gauge German silver, and temporary ranger's, bronze (plated brass). The die was retained by the Service and loaned to the successful bidder whenever new ornaments were required. From the appearance of the extant examples of this early pin, the die must have been rather crude in comparison with later ones.

The USNPS collar ornament was a source of much ridicule since few outside the Service understood the significance of the letters. As a result of this, it was decided at the 1926 superintendent's conference to replace it with a new insignia consisting of the Interior Department or National Park Service seal or words superimposed with the letters US. The Landscape Engineering Division was assigned the task of coming up with design recommendations and the field was invited to send ideas to the chief landscape engineer for consideration. [53] The first offering returned by Thomas C. Vint of the Landscape Division was a pencil sketch of a circle with a large US in the center surrounded by DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR/NATIONAL PARK SERVICE. [54] Shortly thereafter, a blue print was forwarded to the Washington office. After examining the blueprint, Acting Director Cammerer returned it suggesting that the US be made smaller, so as not to fill the entire circle. The following months brought forth a number of drawings of suggested collar devices. Unfortunately, none of these have been found with the correspondence. The favorite seems to have been a shield-shaped device. Apparently the draftsman thought that this design had the inside track, as well, for he included it on one of the initial drawing of the 1928 regulation uniform.

It was decided at the superintendents' conference in 1928 to dispense with the silver and bronze collar devices and to have everyone wear gold ornaments. But no agreement could be reached on the design, so the ornament revision was tabled. In January 1931 it was decided that because of the lack of "inspiration," the Service would keep using the old ornaments until "something really appropriate can be devised." [55] And that is where it stands today. While retaining the same basic design, the ornaments have undergone minor changes over the years. in the late 1930s the fastening device was changed to a screw post like that used by the military. This was changed again in the 1960s to the popular and much more convenient bayonet pin with spring fasteners. In the 1961 handbook, released in November 1959, the colors were changed again. Now only the superintendents and assistant superintendents were to wear gold collar ornaments and everyone else was to wear silver. With the 1971 uniform regulations, gold devices once again became the standard for all uniformed personnel. They remain so today. For a while in the 1980s, plastic collar ornaments were being sent with the uniforms. It was difficult to distinguish these from the metal ornaments, although they would scratch and break if handled roughly. The current ornaments are again of metal.

While technically not an insignia, the ranger hat has become synonymous with the ranger service. Even though Smokey is actually a motif of the Forest Service, most people think of the Park Service when they see him. Similar police hats are also called "Smokey the Bear" hats. It would appear that this "Stetson" style of felt hat evolved from John B. Stetson's first "Boss of the Plains," which he marketed in 1863. [56] This style has long been known as the "ranger" hat, no doubt from being used previously by the Texas Rangers. This style of hat was so popular in the West that "Stetson" became a generic term, like Fedora in the East.

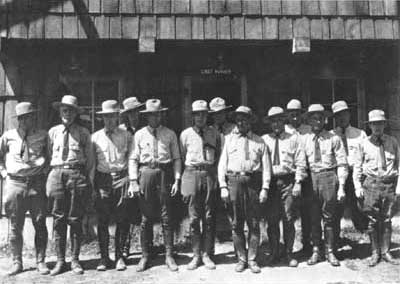

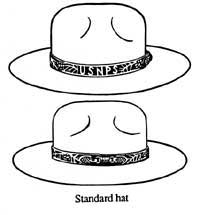

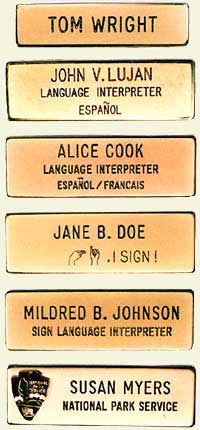

The first hats worn by rangers in the Park Service were "Stetsons" like those of the Army. These were usually creased fore and aft, but there were no regulations on the subject and it was left to the ranger to do whatever styling he wished. When the first "authorized" uniforms were ordered in 1911, they included a "felt camping hat after the Stetson style." [57] It can be assumed that this was a continuation of what the rangers were familiar with. With the ordering of uniforms in 1912, though, an "Alpine" style hat was specified. [58] From the drawing submitted by Sigmund Eisner, it would appear that this was the forerunner of the current stiff-brimmed hat. Photographs bear this out. They show a hat similar to what the rangers wear now, except for a higher "Montana" peak, or pinch. This would seem to prove that when Mark Daniels attempted to formalize the Park Service uniform in 1914, the hat was already being used. [59] The hat was first formally specified in the 1920 uniform regulations. They stated that it would be "Stetson, either stiff or cardboard brim, 'belly' color", a shortening of "Belgian Belly". named after the beautiful pastel reddish buff color of the underfur of the Belgian hare from which some of the finer hats were felted. Here again, this was more than likely a ratification of what was already being worn by the rangers. [60]

The 1932 regulations specified that the "Stetson hat" was to have a "three inch stiff brim," was to be equipped with the "prescribed National Park Service leather hatband," and was to be considered the standard headpiece for use in all National Parks and National Monuments." There were exceptions to the "all." Employees in the eastern parks and monuments and rangers assigned to motorcycle duties were authorized to wear an "English Army Officer" style, of the same material as their uniforms. In 1935, there was some agitation from the field, especially the western parks, for a wider brim to help protect the head from the sun and rain. Office Order No. 324 of April 13, 1936, changed the hat specifications to call for a "Stiff brim 3 to 3-1/2 inches wide, and 4 - 4-5/8 inch crown, side color." Why the color was changed from "belly" to "side" is not known. The John B. Stetson Company, which started selling hats to the Park Service in 1934, initially had trouble with the "side color," and the Service ordered all purchases from the company to stop. In September 1936 the company notified the Uniform Committee chairman that it had "developed the exact color desired by the National Park Service" and was in a "position to manufacture hats and fill orders." It also agreed to replace all hats of the wrong color previously ordered at no charge. The Service rescinded the stop purchase order. [61] Office Order No. 350 of June 15, 1938, changed the color back to "belly" and added three ventilator holes on each side. They were to be arranged in the "form of an equilateral triangle. bottom leg of triangle 1-1/2 inches above brim, legs of triangle 1 inch."

Until 1959, the only instructions to employees concerning the blocking of the hat was to put four small dents in the crown. Thereafter the dents were blocked at the factory for uniformity.

Regarding hat care and maintenance, the handbook stated: "Excessive sweating or the use of hair oil will quickly ruin the appearance of the felt hat. Accumulations of oil around the sweatband and brim will also penetrate the hatband. For this reason, care should be used in placing an old hatband on a new hat or the new hat will be soiled. Clean the hatband with saddle soap. A compound of carbon tetrachloride "Carbona" is available for cleaning hats and the inner surface of hatbands. French chalk may be used to remove fresh grease stains. If the hat becomes wet it can be satisfactorily dried by turning the sweatband outward and allowing the hat to stand on the sweatband until thoroughly dry. Sandpaper or a nail file can be used to remove accumulations of dirt and grease. The Stetson Company will recondition felt uniform hats for $7.50 if the hat is not too far gone." | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In 1959, a straw version of the standard hat was inaugurated for warm weather wear. Its specifications were as follows: Style--"National Park Service" ventilated milan braid material, Belgium Belly color, crown specifications same as for the felt hat. Stiff brim, flat set, average width 3-1/4", marine service curl, leather sweatband and hat [sic]. Indentations in crown, same as for the felt hat. A transparent plastic hat cover was made available for the protection of both the felt and straw hats. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The 1970 regulations concerning women's uniforms brought with it another version of the standard hat. Unfortunately, it was more a victim of style than function. It closely resembled the standard men's hat and while made from a quality felt, it was nevertheless of light-weight material like other women's hats, instead of the heavier men's grade. Because of this lack of body, the brim didn't remain stiff, nor the hat in general, hold up to the rigors of everyday use. Most women that were required to wear a hat, opted for the man's felt or straw, depending on where they worked. These hats have carried over to the present time. Down through the years there has been an array of other headgear, but nothing has stood out as a symbol of the National Park Service like the regulation "Smokey the Bear" felt hat. Hatband & Straps Through the 1920's, ranger hatbands were either the plain grosgrain bands that came with the hat or individualistic replacements by the rangers. At the San Francisco National Park Conference in 1928, the subject of a special band for the ranger hats was brought to the floor for discussion. One design was submitted (description unknown), and another proposed design included a "pressed" style of hatband. There was considerable criticism of the Sequoia cone because it was significant to California alone. It was felt that the design should be more emblematic of the Park Service as a whole. A ranger on a horse, buffalos, and geometric designs were among the motifs suggested. A pack horse drew the most interest because it dealt with park work and had the essence of the tourist and out-of-doors in it.

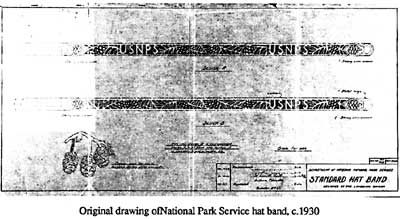

At the 1929 superintendents conference at Yellowstone, the Uniform Committee recommended that a band more in keeping with the identity of the National Park Service be adopted for the ranger hat. Chief Landscape Architect Thomas Vint had a sample hatband prepared. This consisted of Sequoia cones and foliage tooled onto a leather band secured at the left side by ring fasteners. The front had a blank space where the name of the park could be impressed, if desired. This was sent to the chairman of the Uniform Committee, Superintendent Owen A. Tomlinson of Mount Rainier, who forwarded it to the director with the committee's recommendation that it be adopted. The committee thought, though, that USNPS should be stamped on the front instead of the park name, which would have to be done by hand and complicate matters at the various parks. The manufacturer of the sample had provided silver acorns as ornaments, but the committee thought that Sequoia cones would be more appropriate. Nickel silver ornaments could be had for fifty cents each in lots of two hundred, and sterling silver for sixty cents. The total cost of the hatband would be $2.10 with the sterling ornaments. [62]

The hatband was approved on January 16, 1930, with the proviso that the sterling ornaments be used. Associate Director Cammerer thought that the added cost of the silver ornaments was "well worth while" and that they should be mandatory. "The hat band is therefore approved with the ornament of the National Park insignia as an integral part of it," he wrote. [63] When estimates were obtained, it was found that the hatbands, with silver ornaments, could be purchased from a manufacturer in San Francisco in lots of 150 for approximately $2.00 each. [64] The sample hatband was returned to Tom Vint, along with the changes required, so he could make a drawing. The drawing incorporated two styles, utilizing the same information. One style had USNPS on the front only, while the other had it on the front and the back. The advantage of the latter was that it would require a die half the size, at considerably less cost, than the former. The die would make two revolutions to imprint the band, instead of the single needed to make the former. The committee thought that, despite the extra cost, the larger die should be used. [65] In order to reduce the cost to the employees, the Service decided to purchase the die and lend it to the successful bidder whenever new hatbands were required. [66] Since the hatband was paid for by the individual, it could be retained after termination of employment. As Acting Director Cammerer stated it: "This hatband is not an emblem of authority such as the Police Badge worn by rangers and other field men, which must be returned in order such emblems of authority will not be scattered promiscuously throughout the country. On the other hand, it is realized that the desire for retention of some souvenir of employment is uppermost in the minds of many, if not most, of the temporary rangers, and by making them pay for the band it will enable them to retain it along with their hats and collar ornaments." [67] The hatbands were to be made out of four-to-five-ounce "Tooling Vealskin," with a two-ounce cinch strap. The Sequoia cone ornaments and the rings were to be sterling silver. Superintendent Tomlinson received the first consignment of hatbands on May 26, 1930. These were made by a Mr. Brown. It is not known if he made the hatbands personally or just represented the company that did. The finished product made such a striking appearance that the first thought was to restrict them to working employees. However, the director had already authorized that they be personal property, and prohibitions that could not be rigidly enforced would only weaken the regulations already in force. [68] So this idea was dropped. New hat bands and cap chin straps were prescribed in the 1936 regulations (Office Order No. 324, April 13, 1936). "Pending approval of a new design and manufacture of a new die" the existing silver Sequoia cone ornaments were to be used. It is not known at this time what the intended changes, if any, were to be to the hat band ornaments. From drawings and photographs, it would appear that the only change in the leather hat band was to widen it from its original 15/16" to 1-1/8". It was recommended that "at least one new hat band be purchased immediately by each field unit so the standard cordovan color prescribed for all leather articles of the National Park Service will be available." [69] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There was a slight variation in the design in the 1970s, when the manufacturer supplied its own die. These hatbands are made of heavier leather and have a much deeper embossing and the cones have the appearance of pine cones instead of the approved Sequoia cones. With a change of suppliers in the late 1970s the hat band reverted to the original design. Unfortunately, the new bands were of a very inferior quality. They were very thin, with shallow embossing. After a couple of years a new die was cut, and the hatbands once again became something employees could be proud of. With the change of uniform suppliers in the late 1970s or early 1980s the Sequoia cones were changed to gold plate. This was probably to bring them into line with all the other metal on the uniform, which had gravitated to gold over the years. In 1984 they became solid brass. [70] But because the hatbands did not wear out and were usually transferred to new hats, there are still many older rangers sporting the original sterling cones on their hats. Head and chin straps were authorized for the hat in Office Order No. 324 of April 13, 1936. The head strap was to be plain 1/2-inch leather, but the chin strap could be either plain calf-skin or "same design as the hat band," with silver Sequoia fasteners. The 1961 uniform regulations eliminated the chin strap but retained the head strap, although it was now only 1/4-inch wide and to be "worn only in sustained windy conditions." This regulation is still in effect. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Although not officially authorized by the Service, the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC) in Atlanta, Georgia introduced a large 4" x 10" patch in 1984 to be worn on the back of "raid" vests and jackets in conjunction with a new cloth badge on the front. This was inaugurated in order to present a more visible identification for rangers participating in law enforcement activities. This patch consisted of the words "U.S. RANGER/FEDERAL OFFICER" embroidered in a golden yellow on a dark forest green background. As with the accompanying cloth badge, it was an outgrowth of a vest issued to the 1983 class with these two elements stenciled in yellow on it. This patch was phased out with the issuance of the 1991 badge patch, although it still shows up occasionally. The new raid vest has the badge/patch sewn on the left front, with NATIONAL PARK/SERVICE silk-screened on the right in 1/2" gold letters. Instead of a patch, the back has reverted back to having the wearers identification silk-screened on the back, also in large gold letters, although it now says "NATIONAL/PARK RANGER/POLICE." The first two lines are 1-3/4" with POLICE being 4-1/8".

Some employees had been around since long before the formation of the National Park Service, entitling them to an abundance of stars and stripes. "A man with fifteen or twenty years of service looks like a rear admiral," Frank Pinkley commented. [71] This situation was alleviated in 1930 by Office Order No. 204, which introduced gold stars to represent ten years of service. They lasted only until Office Order No. 324 of April 13, 1936. revamped the stripes and silver stars as follows:

The first Length-of-Service (LoS) designation was authorized at the national parks conference held in San Francisco on January 9, 1915. It consisted of a stripe on the sleeve for each five years with the park service. The correspondence authorizing these stripes does not specify color, size, material, nor location, but a photograph of Forrest Townsley taken in 1919 at Grand Canyon National Park shows him wearing three dark bands of tape, presumably black, around the top of the cuff of his left sleeve. These appear to be similar to that worn by Army staff officers. If so, they are probably 1/2" wide. Since Townsley entered the park system in 1904, giving him fifteen years service in 1919, it can be assumed that these three stripes are those mentioned in the above communique. With the 1920 uniform regulations, the single black stripe was regulated to one year of service, with a silver star taking its place for five years. These insignia were to be sewn on the left sleeve of the coat, as well as the shin, with the lowest device being 2-1/2 inches from the end. The stripes were originally to be "narrow black silk braid 3 inches long" but when the regulations were issued they specified "A service stripe of black braid 1/8" wide by 2 inches long" The stars were to be "embroidered white" (silver). Both the embroidered stars and the applied braid were issued on long, three inch wide strips of unbound forest green serge, which may account for the earlier discrepancy. Apparently the edges of the material were to be turned and basted onto the coat sleeve, and in the case of the stripes, leaving two inches of the braid exposed. However, photographs show stripes of varying lengths resulted when left to the individual. Trying to turn the soutache (braid) and keep it neat was also a trick. Although not specified in the regulations, photographs show that the normal practice was for the stripes to be below the stars when worn together, with the stars pointing down. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The new regulations also addressed the problem of the stripe uniformity as well. They were still applied on long 3 inch wide rolls of unbound forest green serge, but now. the stripes, instead of tape, were embroidered 1/8 inch by 2 inches long on it. The order also stated that "When more than one star is worn, they shall be arranged horizontally up to four and triangularly when more than four stars are worn." The "triangularly" part caused some problems later until it was decided that the fifth star would be centered over the bottom four and subsequent stars would contribute to an expanding pyramid. Stars came in units of one to six. Units of one to four were arranged horizontally, while five and up were to be arranged triangularly. (seven stars - unit of four and a unit of three; eight stars - unit of five and unit of three; etc.) Until 1956 the service stars were made up on a continuous roll, same as the stripes. When cut and applied to the sleeve, the serge material often unraveled and took on a ragged appearance if not sewn properly. That year, Charles C. Sharp suggested that they be made up on neat cloth panels, of from one to six stars each. This solved the problem. [72] Also in 1956, with some personnel reaching very long service, it was decided that when seven stars were worn, the bottom row would contain five stars. The 1961 uniform regulations eliminated all the stars and stripes, replacing them with Department of the Interior (USDI) pins for service in ten-year increments from ten to fifty years. These pins, worn at the discretion of the employee, featured a buffalo with U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR in an arc over the top and the year designation across the bottom. They were all bronze, but each year had a different background color. In 1972 the Service switched to pins supplied by the General Services Administration (GSA). These consisted of an eagle over a shield containing the years, with DEPT. OF THE INTERIOR on a ribbon underneath. They were bronze for ten years, silver for twenty years, and gold for thirty years and above, again with different colored backgrounds. The pins changed again in 1987. This time they came from the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) and consisted of the national eagle emblem, complete with wreath of stars over the top. Again they came in bronze, silver, and gold, but there was no wording on them, only the years designation at the bottom. All of the designations had a blue background. In 1990 the Service reverted to the Interior pin. These are now considered personal adornment and discouraged from being worn on the uniform. As in previous cases, the earlier pin continued to be issued until the stock was depleted.

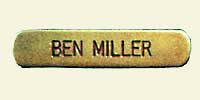

Although name tags had been used prior to 196l, that was the first year they were included in the uniform regulations. As with the other items prescribed, they actually came into use the year before. [73] They were not mandatory, though. The 1961 uniform regulations stated, under Name Tags:

Uniformed employees name tags were to have first name, middle initial and surname only. However, Director Wirth thought that all uniformed employees should wear a name tag when meeting the public. So it was recommended that the uniform regulations be changed to reflect this. It was thought impractical to wear the name tag on field uniforms but consideration might later be given to a "pliable leather" or cloth name tag, similar to those used by the U.S. Air Force, to be sewn on the field uniform. (Many Service helicopter pilot's were later to adopt the sewn on leather name tags on flight coveralls) The location provided for the badge and name tag (for men) was not very becoming to women, it being too low. Besides women did not have breast pockets in their coat (jackets). It was recommended that the name tag be raised to 2" below the notch of the lapel on the right side of the jacket and in a similar location on the blouse. These recommendations were approved by Wirth on October 20, 1960. [74] When the jacket with shawl collar was adopted in 1962, this same general location was still used. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A suggestion was put forward that wearing the name tag, as approved for uniformed employees did not serve the purpose adequately. It was thought that a more descriptive identification should be used. This could be accomplished by several ways. Add (1)(a) "National Park Service" (this was thought to be redundant since it was already on the arrowhead patch): (b) name of park, monument, or other specific area (preferable); or (2) his or her employment category (if feasible on a single line). Wirth considered (a) the best and even though he approved it on December 12, 1961, there are no amendments to the regulations or photographs to show that it was ever implemented. [75] Amendment No.4, January 30, 1962, changed the discretionary part of the above to make it mandatory for all uniformed employees when in dress uniform and meeting the public to wear the name tag. However, it was still optional, at the superintendents discretion, to be worn on uniforms during winter activities, boatmen's uniforms or on the stormcoat. Its location was changed as well. It now was to be worn above the right breast pocket flap on coat or shirt. Also included in the amendment was an identification badge (name tag) for nonuniformed employees who met or dealt with park visitors in the normal course of their work. This badge served to identify them as members of the National Park Service. The badge was to be made out of the same material (dark green plastic laminate) as the ranger name tags. It was to be 3" x 1-1/4" with a 1" arrowhead insignia on the left side and three lines of text. The first line consisted of "National Park Service" in lower case; the second line was the employees employment category, i.e., PARK ENGINEER, ROAD FOREMAN, SECRETARY, etc.; third line was for employees name in lower case. (first, middle initial, surname) These name tags were made by the Yosemite National Park Sign Shop for $2.00, with name, or $1.50 without name.

A similar name tag was also used by park maintenance personnel. The badge was made out of the same material as above along with the arrowhead on the left and "National Park Service" on top, but "Park Maintenance" in lower case was on the bottom. with the employee's name in green embossing tape between them.

The above tags were worn until 1969, when the style of the ranger name tag was changed to "gold metal plate with cordovan colored block letters; corners rounded." This tag also had the two pin keepers, but now it was to be worn over the right pocket. This tag was also issued to maintenance supervisors as well. Although the 1974 uniform regulations first specified a new name tag for uniformed maintenance personnel, photographs show this had been introduced in the late 1960's. Instead of being detachable, this new name tag was embroidered and sewn on the uniform centered above the right breast pocket with the bottom flush with the top of the pocket flap. It consisted of white block lettering on a green background with a brown border. However, though not addressed in the regulations, there were actually two cloth name tags, one over each pocket. The one over the left pocket contained NATIONAL PARK SERVICE in 1/2" white block letters, per the regulations, while the other contained the first initial and last name of the employee in white script. Sometime in the late 1970s or early 1980s, the arrowhead patch was added to the shirt, making the National Park Service patch redundant and it was eliminated. The name patch is still worn today. These name patches were and still are, furnished by the Lion Brothers Company of Owings Mills, Maryland. The name patches are sent to the uniform supplier blank and the name is stitched in there.

In 1981 the name tag was changed to the larger rectangle style used today. It retained the gold finish. In keeping with the Service's goal of trying to assist all visitors, new name tags were issued to sign and foreign language interpreters. These were the same as the standard name tag, only expanded to accommodate the additional lettering. Language interpreter tags had been worn before this, but they were separate from the employee's name tag and usually purchased locally by the park. This was the first time that they were made part of the uniform regulations. Included with these tags was one for non-uniformed personnel. This consisted of the same gold badge, but it had the NPS arrowhead emblem on the left side. Under the employee's name was NATIONAL PARK SERVICE. This name tag was not to be worn with any uniform, although in the mid-1980s it was worn by rangers in some parks. These badges were made by the Reeves Company, Inc. of Attleboro, Massachusetts.

The 1920 uniform regulations brought forth a plethora of insignia. In addition to the three USNPS collar ornaments, there were 14 patches for the sleeve. These sleeve insignia, or brassards, were to identify the rank and position of the various park employees. They were to be worn between the elbow and the shoulder on the right sleeve. These insignia were embroidered on the same material as their respective uniforms: forest green serge for officers and forestry green wool cloth for rangers. All were to be 2-1/4 inches in diameter with a 1/8-inch "light green" border. There were three categories of brassards: for directors, officers, and rangers. The basic device for directors was four maple leaves. These were to be embroidered in "golden green," with a star in the center. The only difference between the director and assistant director was that the former had a gold star and the latter a silver one. The basic device for officers was oak leaves, three for chiefs and two for assistants. The oak leaves were a "shaded golden yellow" with "dark brown" branches. Superintendents and assistant superintendents had "golden brown" acorns with "darker brown" cups and branches, three and two, respectively, as their identifying devices. All other officer identifiers were embroidered in white. These identifiers were:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Although foresters were considered to be officers, their brassard did not have the customary oak leaves. Instead, for some unexplained reason, the chief ranger patch was utilized with white crossed axes. The basic device for the rangers was stated as being the Sequoia cone, while in actuality the common denominator was a wreath. Sequoia cones denoted the relative positions of the various permanent rangers. The chief ranger had three, the assistant chief ranger two, and the ranger one. All of these were within a "dark green" wreath. Temporary rangers had only the wreath. Sequoia cones were "light brown" with "dark brown" details and branches. [76]

Although the 1920 regulations listed supervisors and assistant supervisors as officers, no special sleeve device was assigned to them. The 1922 order for sleeve insignia corrected this oversight and added four more officers to the fold:

GAME WARDEN could also be added in white beneath the circle on any brassard. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

When the contract for insignia was drawn up in 1924, a new sleeve brassard was added. This insignia, designated "unclassified," was to be used by all uniformed officer personnel not otherwise covered under the regulations. It consisted of two oak leaves on a branch. Because of resistance to the park naturalist sleeve brassard, no new ones were ordered in 1924. The park naturalists preferred to wear the "unclassified" insignia instead. Since the park physicians also wore the unclassified insignia, it can be assumed that they objected to their insignia as well.

A design for a new park naturalist sleeve insignia was submitted by Ansel F. Hall, chief naturalist of the Service, in March 1925. Hall's original design has not been located, but correspondence indicates that it was based on an eagle. It was considered too intricate to be embroidered on the small patch and a simpler design was worked up, following the standard practice of the other sleeve brassards. Two samples were sent to Hall, both contained the three oak leaves of supervision. but one had a bird on it and the other a bear's head. Correspondence states that due to a lack of brown thread, the supplier worked the bird and bear's head in white, but more than likely, this was just a continuation of the practice of embroidering the identifier in that color. Hall approved the bear, but objected to the shape of the bear's head as being too round. He drew a corrected version and returned it to Washington. Thus, by 1926 the park naturalists had their own distinctive insignia. Park ranger naturalist, a temporary, or seasonal position, fell under the ranger category and as such wore a bear's head, worked in shaded brown, surrounded by foliage. As the Service diversified. holders of new positions clamored for their own sleeve identification. Because the majority of these positions were not in the ranger field, they considered themselves officers. This situation was rapidly getting out of hand until the 1928 regulations resolved the matter. The matter of the officer badge had been decided in 1921 by declaring that only those officers having a command function were to wear it. Now it was determined that those same individuals were the only ones to be considered officers. All others, with the exception of the rangers, were classified as employees. This resulted in the rangers being elevated to a position within the Service more equitable to their duties and responsibilities in the field. At the same time it was decided to eliminate the sleeve insignia from all but the ranger force.

At the 1934 superintendents' conference, it was decided that the sleeve brassard on the ranger uniform was an unnecessary expense and served no useful purpose. Even so, they remained in the regulations for several more years. Although there is photographic evidence that the sleeve brassards were worn as late as 1946, patches would not officially return to the National Park Service uniform for many years.

In the early years the coat was usually kept buttoned, negating the need for a tie tack or bar. Occasionally, a stick pin or other such ornament shows up in a photograph, but for the most part, nothing was used to hold the tie down even when the coat wasn't worn. The first tie ornaments were authorized on February 13, 1956. Amendment No. 12 to the 1947 uniform regulations states, "If a tie clasp is used the National Park Service emblem tie clasp is suggested." This first Service tie clasp consisted of a hidden bar with a chain looped over the tie and a small arrowhead emblem, in gold or silver, suspended from the middle of the chain. This was only a suggestion, and photographs show that a lot of employees used plain chain ornaments as well as bars. As fashion changed, so did the ornaments. The arrowhead was next put on a bar, then a tie tack. One did not necessarily succeed the previous style. In 1965 all three were available from Balfour Supply Service, Inc.

With the 1956 uniform regulations, the wearing of a tie clasp remained optional but if one was worn it had to be the National Park Service emblem (arrowhead). The 1961 uniform regulations still listed tie ornaments as optional,although now it was specified that if one were worn, it would be the "official National Park Service silver (gold for superintendents) tie tack." When worn. tie tack was to be "centered at third button down, starting with the neckband button, the clutch pin piercing both tie ends and the anchor chain bar secured through the shirt buttonhole." As stated previously under badges, in January 1962 a silver "tie tack style" pin was authorized as an option for women employees, in lieu of the regulation badge. Although this pin conforms to the size and design of the men's tie tack, it was stamped from a different die. All surface features are either raised or diked, as if the pin was originally designed to be enamel-filled. Word from the field is that they were crudely constructed and the pin on the back was in constant need of repair. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In late 1963, authorization was given for the wearing of enameled tie tacks, or "pinettes", as they were called, instead of the plain gold or silver. These were of gold or silver with a multi-colored enamel fill. Either color metal could be worn, but superintendents were to designate which, in order for their entire park staff to be uniform. [77] In 1964. V. H. Blackinton and Co. began making these tie tacks in "HiGlo" (enamel) and "Rhodium" (enamel) for $2.25 and $2.50, respectively. These enameled tie tacks could be used by both uniformed and non-uniform employees. As stated in the Arrowhead section, in 1966. the National Park Service initiated a service-wide program entitled MISSION 66. An outgrowth of this, and a pet project of Director George B. Hartzog, Jr., was another project called, PARKSCAPE USA. It's emblem was three intertwined angles surrounding three round dots. This emblem was also converted into a tie tack and authorized to be worn in place of the arrowhead, if so desired. Most uniformed personnel, however, preferred the arrowhead, with it's symbolism, to the abstract PARKSCAPE design. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

With the design change of Interior's seal in 1968 and Director Hartzog's pressing his PARKSCAPE USA agenda, one of the casualties was the arrowhead tie tack. The small triangular pin be came the official tie tack of the National Park Service. With the Interior seal reverting back to the buffalo in 1969, the attempt to replace the Arrowhead with the PARKSCAPE symbol was abandoned. The Arrowhead shoulder patch was reinstated, but the latter was retained for the official tie tack. The little triangles. now gold and green enamel, remained in use until 1974, at which time the arrowhead once again came back into use. In 1976, the country's Bicentennial brought forth a number of decorations for the uniform. One ornament was an adaptation of the standard arrow head tie tack with "American Bicentennial" on a curved bar across the top. These were made by Blackinton. This tie tack was authorized as a replacement for the standard tie tack in a Memo by Acting Director Raymond L. Freeman on April 16, 1976, and continued until December 31, 1977. It's use was not mandatory, but, nevertheless, strongly encouraged. Cost was $3.25 per 100. Service uniforms were becoming very cluttered. After the Bicentennial fanfare was over, reaction set in and the uniform was stripped of extraneous paraphernalia. Only the basics were retained: collar ornaments, badge, arrowhead patch and tie tack. The uniform remains in this condition today.

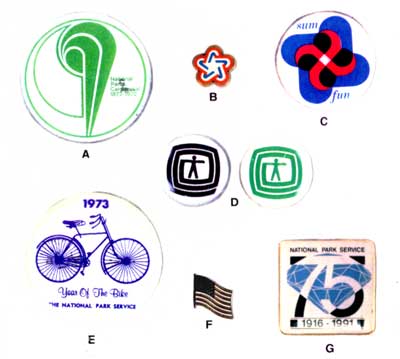

After World War II, returning uniformed Park Service employees were allowed to wear their military uniforms on duty, along with any decorations, for 60 days. After which time, they had to don their Park Service uniform but were still authorized to wear "any ribbons to which they are entitled for service in the Army, Navy, Marine Corps or Coast Guard." [78] Apparently this allowance was loosely interpreted, because photographs show rangers wearing military medals and decorations, as well as ribbons. This practice continued until rescinded in the 1961 uniform regulations. The 1956 uniform regulations authorized those employees who had received Departmental Awards either for "distinguished service" or "meritorious service" to wear the appropriate lapel emblem as part of the official uniform. The Department length-of-service emblem (USDI) was also authorized to be worn. The 1961 regulations state that these emblems are to be worn in the left lapel buttonhole, but the sketch that accompanies it shows the length-of-service pin above the button on the right top pocket flap. Apparently the pin placement was changed prior to the regulations being issued and the sketch overlooked. The 1961 uniform regulations also authorized the wearing of temporary buttons: "At the discretion of the superintendent, temporary fund drive buttons for charities and public benefits recognized by the National Park Service may be worn on the uniform on the left lapel on jackets or on the flap of the left pocket on shirts." Although the 1961 regulations were the first to address the issue, pins and tags had adorned the uniform from the early years. The most notable occasion was the American Bicentennial and its myriad symbols. But there were many others. The Centennial of the National Park System saw a stylized geyser emblem, in the form of a pin, receive much wear. There were also several environmental programs under way at the time with their own symbols. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This practice is continued today with pins tor special occasions such as the Service's 75th anniversary in 1991 still periodically authorized. There are too many of these pins to be treated in detail here, but the following small assortment is representative of this type of decoration.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

nps-uniforms/1b/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 01-Apr-2016