|

National Park Service

National Park Service Uniforms The Developing Years, 1932-1970 |

|

THE DEVELOPING YEARS

Up until the 1930s, the National Park Service had been content to tinker with recognition symbols to be applied to the coat. These were added and removed as they endeavored to iron out the wrinkles and come up with a sensible, yet practical uniform. All the effort was concentrated on the basic uniform and consequently the rangers ended up with a very nice suit of clothes that worked well in most of the western parks during the spring, summer and fall seasons. The "officer and men" mentality that prevailed in those early years resulted in the "men" wearing a uniform of heavy grade material not really suited for the warmer eastern parks. This was corrected in 1928 when the rangers were authorized to wear uniforms of the same material as those of the officers.

A soft cap, based on the style worn by British army officers at that time, had been specified in 1928 for motorcycle patrol use, although this was later expanded to include warm weather parks, especially in the East. Other than the hatband authorized in 1930, the first documented addition to the ranger's wardrobe for servicewide use in this decade, was a raincoat.

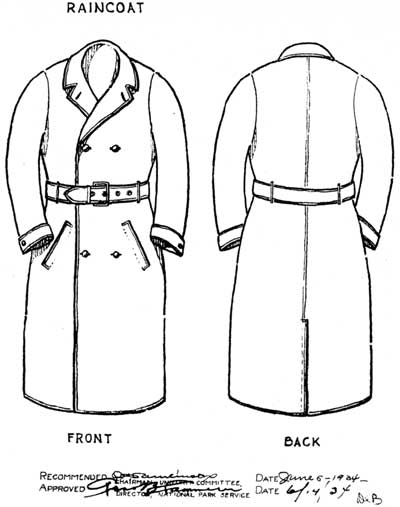

The need for a raincoat had been suggested at the 1932 Conference, and in fact, an overcoat and raincoat had been specified in the 1932 Regulations when they were issued, but apparently no designs had been formulated for these items, leastwise the raincoat. For some reason, drawings were not made for this item until two years later. Owen A Tomlinson, superintendent of Mount Rainier National Park and chairman of the Uniform Committee submitted these drawings to the Director's office on June 5, 1934, where Director Arno B. Cammerer approved them on June 14. [1]

A raincoat was incorporated into the Uniform Regulations in 1932. However, it would appear that this wasn't finalized until this 1934 drawing was signed by Director Arno B. Cammerer approved this drawing on 6/14/34. NPSHC-HFC RG Y55 |

Because of the dearth of correspondence and documentation from the 1930s, it is very difficult to pinpoint when some uniform articles were introduced. Some articles credited to the 1932 and 1936 regulations may have been introduced earlier, or as in the case of the raincoat, later. Office Order 204 was published in 1930 and revised on June 7, 1932, but only the revised version has been found. What little official correspondence there is alludes to several office orders concerning uniforms being published between Office Order 204-revised and Office Order 324, published on April 13, 1936, but these have not come to light. The same is true between 1936 and 1940. We must therefore assume that any changes between these dates occurred on the latter, until one of these lost office orders proves otherwise.

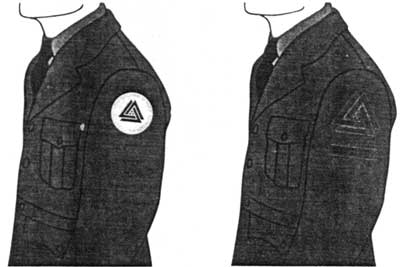

Sleeve patches (know as brassards) to distinguish rank and position were eliminated for all personnel, with the exception of those assigned to the ranger force, in the 1928 Uniform Regulations. The regulations state that the basic emblem for the ranger was to be the Sequoia cone, while in fact the common denominator was the wreath. The Sequoia cone, or in the case of the Ranger-Naturalist, the bear's head, served as the identifier. NPSHC-Artwork by R. Bryce Workman based on originals in National Archives RG 79-HFC RG Y55 |

It took the NPS many years to shake the military mentality it had acquired during the Army's attachment to the parks. There are some vestiges of this way of thinking still around to this day. At the 1934 superintendent's conference in Washington, D.C., the uniform was on the docket, as it had been every year, and ways of sprucing it up and making it more attractive were discussed.

Sleeve brassards, or patches had been introduced between 1920 and 1926 to show the status of all uniformed NPS personnel. All of these except for those worn by the rangers were eliminated by the 1928 regulations. At the 1934 conference, it was deemed that those worn by the rangers "served no useful purpose" and it was thought their use should be discontinued.

This recommendation was apparently ignored since the Ranger Insignia remained in the Regulations, at least through 1936. They were gone by the 1940 Regulations, probably removed with the lost 1938 specifications. Even so, they continued to be worn, at least until 1946, as at least one photograph testifies. This was probably because a ranger could wear his uniform as long as it was serviceable. To have removed the patch from the sleeve of a coat several years old would have left an unbleached circle on the sleeve.

Out of these discussions came the decision to experiment with a two-tone uniform similar that worn by the Army. [2] The coat would remain the same "forest green", but the breeches were to be beige, or khaki, similar to the new summer uniform, instead of the Army's "pinks". Only superintendents and custodians were to wear it during this experimental period, but if agreed upon, it would become the Service standard.

There are no known photographs of anyone wearing this uniform, but the idea may have been around for some time. The only image showing what appears to be this combination is of Superintendent William M. Robinson and National Park Service Director Horace M. Albright and his wife Grace, during a visit to Colonial National Monument on May 14, 1933. Although the color can not be ascertained since the image is black and white, it can be seen that the trousers are a different color than that of the coat. Robinson was of the opinion that the rangers at Colonial should be wearing white uniforms instead of the khaki that had been authorized, but he was turned down.

Director and Mrs. Horace M. Albright, along with Superintendent William M. Robinson, Jr. at Colonial National Monument (later National Historical Park), May 14, 1933. Robinson is wearing a 2-tone uniform. The matter of a 2-tone uniform was not brought forward until the 1934 Conference and although not noted in the official correspondence, Robinson may have been the instigator of its consideration. NPSHPC-HFC#86-51 |

Tomlinson made arrangements with the Fechheimer Brothers Company, uniform manufacturers of Cincinnati, Ohio, to furnish breeches made from a dark tan or beige elastique, of the same weave and quality as the uniform coats, in 18-19 ounce for $9.50. These could also be obtained in 16-ounce material for summer wear at $8.85 a pair. Employees could purchase material if they wished to have their own tailors make the experimental breeches for them.

Apparently all of the superintendents and custodians were urged to participate in the experiment, but it is not clear how many did. After trying the new breeches for a year, or until the next conference, they were to advise the director's office whether they considered the uniform specifications should be amended to include this new material, and if so, any changes they thought necessary. [3]

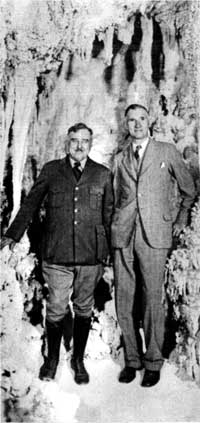

Superintendent, Col. Tom Boles (left) Superintendent, [John R.] White (right) In the Big Room. Carlsbad Caverns National Park, February 1937. Boles is also wearing breeches that are lighter than his coat. It can't be determined from this black and white photograph but it doesn't appear to be the "khaki or beige" color recommended at the 1934 Conference. NPSHPC-CACA#7515 |

Ranger, 1934. This dapper ranger in Class A uniform from Yellowstone National Park rivals even "Dusty" Lewis in impeccability of dress. Even his breeches have creases. NPSHPC-YELL#130,151 |

While the majority that responded thought that the light colored breeches with the dark coat made a pleasing appearance, most of those participating considered them too hard to keep clean, thus negating the overall sharp image that they wished to portray. Consequently, the idea was dropped.

For some time a movement had been afoot toward the "pepping up" and standardization of the National Park Service uniform. At the conference, in addition to the experimental breeches, several other suggestions were put forward regarding the rest of the uniform.

The present coat was considered to be rather drab and it was thought that it could be "sharpened" up by adding shoulder straps. In addition, it could also be made to stand out by adding red piping to these shoulder straps and the pocket flaps as well.

It was suggested that the hat brim be made wider to provide better protection from the sun. And since there seemed to be no answer to the multi-shades of green ties, it was thought the color might be changed to black. Special tan shirts were put forth, with or without shoulder straps, to be worn when not wearing a coat.

As in the past, when a uniform change was contemplated, these suggestions were offered to the field for comment. The response to the shoulder straps was lukewarm, but the red piping received a decided thumbs down. Comments like "bell boy's" and Marines lace the replies. The wider hat brim was fine, but the majority preferred the dark green tie, providing a uniform color could be obtained. Most thought that the shirt should be able to be worn with or without the coat and that tan was not a good color. It showed dirt quicker and most other organizations as well as the military wore it. They thought that the gray shirt, then in use, was more distinctively National Park Service. [4]

Without a central quality control, deviations in the style and design of the uniforms had begun to creep in. Many officers and employees were ordering uniforms from the manufacturers made differently than prescribed by the regulations. These changes included such things as: different shaped lapels; unauthorized buttons on sleeves; fewer than the prescribed number of buttons; cuffs on coat sleeves; omission of vent in back of coat; change in design of pockets; and variations in the cut of the breeches. Jodhpurs [5] were very popular during this period and many rangers thought they provided a neater appearance.

In addition, regulation hatbands were being installed on hats without removing the cloth grosgrain band that came with the hat. Feathers and "other trinkets and ornaments" were being added to the hat band, as well, making for a very cluttered head covering. Riding and full-lace boots, as well as old style puttees (spiral wound strap) were being worn instead of the regulation "field boot" (which laced at instep and outside of calf) or the new leather leggings with the spring attachment fastener.

Arno B. Cammerer, Director, National Park Service (1933-1940) NPSHPC-HFC#268X |

On January 14, 1935, Director Arno B. Cammerer felt compelled to send out a memorandum to all of the field offices admonishing them to pay more attention to what was being worn in the parks. He felt that "Special attention should be given to the wearing of uniforms and it should be remembered that the purpose of a uniform is to make the ranger conspicuous." Things that were to be watched were:

"Pockets that were more ornamental than serviceable; coat should be kept buttoned, when worn; collar ornaments should be placed on collar, not on lapel; boot and shoes laces tucked in; and hats were to be worn "square" upon the head or slightly "rakish"".

He ended by telling them to "Wear a uniform as if you are proud of it." [6]

On August 9, 1935, evidently, to assist the men in the field in conforming to the Office Order No. 268 uniform regulations, Acting Director Tolson forwarded a list of manufacturers and dealers in uniform equipment (Appendix A) along with blue prints showing the correct National Park Service uniform to all the field offices to be distributed to the men in the parks. [7]

Apparently, the move to switch from the dark green to black necktie, and the fields overwhelming rejection, caused the Uniform Committee to try again to solve the problem. Obtaining ties of a uniform shade of green had plagued the Service since they were prescribed in the 1920 regulations. It was finally decided that a dark green Barathea silk, four-in-hand necktie would fit the bill. These, hand-made with a "pure wool" lining, could be purchased from Schoenfeld Brothers, Incorporated, makers of "Fashion Craft" neckwear of Seattle, Washington, for $7.25 per dozen, plus postage. Fechheimer could also furnish these, but no price was given. In both cases orders had to be at least a dozen or more. [8]

National Park Service uniform button. This design originated in 1912 when Sigmund Eisner, the uniform supplier at that period, modeled it after the 1906 ranger badge. Early buttons had a lacquer finish which had a tendency to chip and peel. NPSHC |

In the beginning of 1935, the Waterbury Button Company (today known as the Waterbury Company) of Waterbury, Massachusetts, began furnishing buttons with an "acid treated" finish. They claimed that this type of button would hold its color and wear much better than the lacquered buttons previously furnished. They cost $7.50 per gross for the coat size and $4.75 per gross for the vest or pocket size, as opposed to $5.00 and $3.75, respectively, for the lacquered variety. This process is still used today. [9]

Office Order No. 321 was sent out to the Field Offices on March, 16, 1936. The cover memorandum states "that the employees herein authorized to wear the uniform may continue to use articles of uniform authorized by Office Order No. 268, now in effect, until such articles are worn out, provided such use shall not exceed beyond December 31 1936." Without a copy of Office Order No. 268, there is no way to determine just what "articles" were deleted from the new regulations.

There is some question as to when the following uniform regulations came into being. They probably originated with Office Order No. 321, but they could have been incorporated in Office Order No. 268 or possibly some earlier unknown Office Order issued between Office Order 204 revised (June 7, 1932) and 268. Since there are no known copies of these documents, the regulations' origination date can not be determined at this time. The only thing certain is that they were in effect by April 13, 1936 when Office Order No. 324 took effect.

The new uniform regulations now provided for three different uniforms: Standard, Fatigue and Winter Sports Patrol. The Standard uniform remained the same except for the following:

Temporary Ranger Cosby, Sequoia National Park, 1935. Cosby portrays what the well-dressed National Park Ranger was supposed to look like. Unfortunately, not all rangers managed to hit the mark. NPSHPC-SEKI#76-116 |

Roger W.[Wolcott] Toll, Superintendent, Yellowstone National Park (1929-1936) Toll was an active participant in the uniforming of the Service. During off-seasons, he was chief investigator of proposed park and monument sites for the National Park Service. Toll's image was lifted from the group shot of participants at the 1934 Superintendent's Conference and superimposed on a picture of the front of the old Interior Building to make this composite photograph. NPSHPC-Schutz photo-HFC#64-244 |

Hat - the brim width was now 3" to 3-1/2" and for the first time the crown was specified to be 4" to 4-5/8", depending on what suit the wearer. And for some unknown reason, the color was changed from "belly" to "side".

Cap - now to be worn only by rangers on motorcycle duty.

Coat - could now have either a three or four button front. (probably depending on the size of the individual)

Trousers - cuffs to be increased from 1" to 1-1/2".

Field boots - leather leggings were no longer to be worn. Shoes were to be worn when wearing trousers, but they were to be cordovan, not black, and were to be worn with dark brown socks.

Shirt - Gray shirt could now be gabardine or cotton, as well as flannel. White shirt was to be worn for formal occasions only. In addition a field shirt was added. It was to be steel gray and have an attached collar, shoulder straps and two large, pleated pockets fastened with buttons. It could also be made out of flannel, gabardine, or cotton.

Tie - Dark green barathea silk with full wool lining.

Raincoat - Color changed from "deep sea green" to forestry or olive green. It was to be made from 12 to 18-ounce waterproofed cloth such as "Alligater" (a forestry green cravenetted [10] gabardine).

The Fatigue uniform was prescribed for informal wear such as patrol or general field duty where the ranger would not be coming into contact with the public and where the standard uniform would be inappropriate. This was the introduction of the short coat, or jacket, the forerunner of that worn today. And apparently since a lot of the rangers were wearing them anyway, the Uniform Committee bowed to the inevitable and authorized the wearing of the lace up boot. The fatigue uniform consisted of:

Hat — regulation

Jacket - National Park Service field jacket: short jacket with 2" waistband with adjustable buckles at sides. Jacket fastens in the front with full-length talon fasteners (zipper). Two large plaited breast pockets with flaps fastened with small regulation NPS buttons. A double layer of material is applied from the top of the pockets, over the shoulder and the full length of back of jacket. Lower part of back provides a large pocket, (like some hunting coats) closed by zippers under each arm. Color not specified but was forest green.

Breeches - regulation

Trousers - regulation style made from canvas or any waterproof material of a forestry green or tan color.

Shirt - regulation wool or cotton.

Tie - optional, at discretion of superintendent.

Boots - Heavy 16" top, leather lace-up style or regulation field boot.

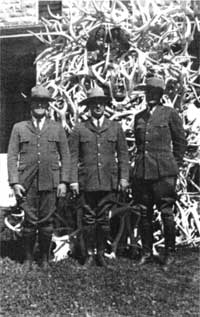

Permanent Staff Naturalist Department 1934 [Yellowstone National Park]. They are standing in from of the famed Elk antler stack at Yellowstone. Crowe and Bauer are wearing the regulation "puttees" while Kerns has on the dress boots. Left to right: George Crowe; C. Max Bauer; William E. Kerns NPSHPC-YELL#130,199 |

Jr. Landscape Architect Howard Baker, March 12, 1934. Unauthorized details, such as lapel buttonhole, were still creeping into the uniforms. NPSHPC-ROMO# 3280 |

Badges, collar, and rank insignia were to be worn on the field jackets and on shirts when worn without coats or jackets.

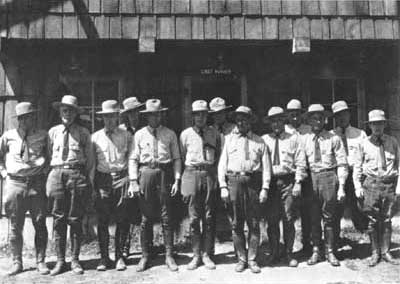

Rangers Force at Sequoia National Park, c.late 1920s. Prior to the 1936 uniform regulations, belts of all descriptions were worn by rangers. Also note the variety of ties. Davis & Brooks are wearing unauthorized footwear. Left to right: Packard, Lew Davis, Kerr, Williams, Brooks, Cook, Peck, Dorr, Fry, Alles, Smith, Sprigelmyre, Gibson NPSHPC-HFC#86-246 |

1934 uniform shirt & breeches. This image shows a ranger from one of the western parks without his coat. His breeches and service boots show very clearly. Even the fact that his boot laces aren't tucked in. NPSHPC-ROMO#11-15-1-3 |

The third uniform, the Winter Sports Patrol was for National Parks and areas with established winter sports seasons. It consisted of:

Cap - NPS ski style with adjustable earflaps and USNPS embroidered in gold on the front.

Jacket - NPS style

Trousers - Ski style with full length cuffs, 20", or larger leg and knit ankle cuff.

Boots - conventional ski boots

Socks - Heavy wool with dark green top or olive green or steel grey ski leggings.

Parka - Light weight, waterproof forestry green or steel grey material, with or without hood. It could be either waist or knee length.

The Regulations stipulated that only those "National Park and monuments employees whose duties are chiefly to attract and to contact park visitors and to protect the areas adminstered(sic) by the National Park Service" (rangers, superintendents, naturalists, police, etc.) were to wear the standard Service uniform. No one was to wear the uniform when not on a "duty status."

Possibly because the coat was usually worn with the uniform, belts do not appear as an article covered by the regulations until 1936. Earlier photographs confirm the prior absence of any standard belt or buckle. Probably the only thing covering belts was the stipulation that all leather would be of a cordovan color. The new regulations specified that a "Forestry green, web-waist belt, 1-1/8" wide, with buckle approved by the Director, [probably the web belt style buckle being worn by the military] is prescribed for wear when breeches are worn with or without coat."

The 1921 superintendent's badge (1921-1936-silver) NPSHC |

Office Order No. 321 was superceded by 324 on April 13, 1936. The new regulations resurrected the small gold badge originally worn by Directorate officials (1921-1928) and awarded it to park superintendents. Assistant superintendents continued to wear the nickel-plated badge.

The usual field inquiry system may have been instituted prior a decision being made to change the regulations in 1936. It's quite possible that the ideas for a new superintendent's badge were solicited from the field, although there isn't anything in what little official correspondence that survives to support this. There is, however, at least one sketch from this period showing a proposed model for a superintendent's badge. It utilizes a modified version of the standard shield badge design with SUPERINTENDENT on the top.

Proposed(?) 1936 Superintendent's Badge. The origin of this sketch is unknown, but since it is dated 1936, the year the superintendent's badge was changed, it was probably submitted for consideration as a possible candidate for the new badge. It is basically a modified version of the badge being worn at that time. NPSHC-HFC RG Y55 |

The ranger badge had been changed in 1930 from the original two-piece (round medallion soldered to face of the shield) to a simple, less expensive one-piece badge, utilizing the same design. There was a movement afoot at this time to change the design of the badge to incorporate more information on the face and this cost cutting method was no doubt done in anticipation of this change. The 1930 style badge was retained, however, but although not covered in the regulations, it began to be dapped, or curved, so as to lie close to the coat. This is born out by extant examples known to have been worn during this period.

New hat bands and chinstraps were also prescribed in these new regulations along with a change in the Length-of-Service decorations. With some of the Service employees having been around since long before the formation of the bureau, an abundance of stars and stripes was being worn on their sleeves. To alleviate some of this clutter, a gold star was initiated in 1930 to represent 10 years of service.

A band 5/8" wide, was authorized in 1915 to denote five years service in the National Park Service. This was changed to a 1/8" piece of braid sewn on a piece of the coat material in 1920, which in turn was superceded by a 2" stripe embroidered on the material in 1936. The stars were embroidered on the coat material from 1920 until changed in 1956. NPSHC |

But now, the mish-mash of black stripes and gold and silver stars adorning sleeves made the appearance of the uniform worst than ever. This was one of the problems addressed by the new regulations. The stars and stripes were revamped as follows:

"For each year of completed service a black braid, 1/8" wide and 2" long.

After the first star is earned, bars shall be discontinued to indicate service of less than five-year periods. For each five-year period of completed service, a silver embroidered star.

The service insignia shall be worn on the cuff of the left sleeve of the coat and overcoat, the lower stripe or star shall be placed 2-1/2" above end of sleeve. When stripes and stars are worn, stars shall be placed uppermost. When more than one star is worn, they shall be arranged horizontally up to four and triangularly when more than four stars are worn."

The "triangularly" part was to cause some difficulty later with everyone interpreting it his own way. This situation was not corrected until 1942. Another aspect of the stars that wasn't addressed in the regulations was which direction they were to point. Photographs and the later patches indicate that this was to be down, not up as one would suppose.

The new regulations also addressed the problem of stripe uniformity. Up until now, the stripes had been a 3" piece of "narrow silk braid" stitched to a 3" wide strip of uniform fabric the edges of which were to be turned under and stitched to the coat sleeve. Therein lay the difficulty. With each person turning the edges under, the regulation 2" length was seldom attained. The new stripes still came on 3" wide strips of uniform fabric, but now the 1/8" by 2" stripe itself was embroidered on it.

Another problem that had plagued the Service from the beginning was the color of the wool used in the uniforms. With each manufacturer's conception of forest green being different, the uniform committee thought it prudent to standardize on one cloth manufacturer in order that the uniforms remained uniform. Consequently, the "American Woolen Mills, Shade No. 168, forestry green" was selected and the superintendents and custodians were instructed to request this material when "ordering their elastique and tropical worsted or gaberadine(sic) cloth uniforms." [11]

Guy D. Edwards, Superintendent, Grand Teton National Park, 1936. Edward's boots reflect the reason for the modification. Boots from this period had a tendency to wrinkle above the ankles, especially on people with thin legs. His sleeve has two stripes and one star denoting 7 years service. This is also the year the small superintendents badge was changed from silver to gold. NPSHPC- George A. Grant photo-HFC#201-T |

The reasoning for changing the hat color from "belly" to "side" was not given, but this change in definition initially gave the John B. Stetson Company a problem. Stetson had began furnishing hats to the Park Service in 1934. How this shade differed from "belly", [12] if in fact it did, is unknown, but the color of the hats provided by Stetson apparently was not correct because Hillory A. Tolson, acting associate director, ordered all purchases of hats from that company to stop.

These difficulties were corrected by September and the uniform chairman notified the field that the company had "now developed the exact color desired by the National Park Service" and that his stop order of July 7th was rescinded. Along with the color correction, Stetson also agreed to replace any hats purchased after issuance of Office Order No. 324. [13]

A special meeting of superintendents was held at Washington, D.C., in February, 1936. One of the items on the agenda was field boots. After much discussion, a recommendation was formulated and forwarded to the director's office regarding the changing of the NPS boot to "a field boot differing slightly from the conventional design, having a specially shaped leg which decreases the tendency to wrinkle".

Companies that manufactured boots were contacted and an agreement had been reached with the Teitzel-Jones Company of Wichita, Kansas, whereby they would assemble the boots to order, leaving the back-seam open. These would then be shipped to the prospective buyer to try on to insure proper fit and satisfaction. After try-on, the boots were to be returned to the factory, along with such suggestions as necessary regarding the fit of the feet and a form showing exact leg measurements. The boots would then be completed in accordance with any special instructions and leg measurement form and the finished product returned to the purchaser. Cost of a pair of boots was $26.00, plus $1.60 parcel post and insurance. [14] Teitzel-Jones furnished boots to the Service as long as they were included in the regulations.

Up until the issuance of Office Order No. 350, on June 15, 1938, National Park Service Uniform Regulations were simply four or five pages of written specifications, but beginning with that Order the Regulations were presented in a booklet format.

Until November 22, 1940, when a new manual was issued, whenever a change was ordained new pages were forwarded to the parks to be inserted in their existing manual with instructions for the parks to destroy the old sheets. This makes it difficult to follow the nuances of uniform development in some cases, during this period. We know what the final evolution is but not what was originally prescribed.

Unfortunately, because of the above, only fragmentary sections have survived. It is assumed that the regulations remained basically the same with only the extant change sheets in the archives being at variance.

Interpreter guiding visitors through the fort at Castillo de San Marcos National Monument, 1958. Even though the Pith helmet color had been changed from forest green to sand in 1940, he is still wearing the earlier forest green model. The arrowhead patch on his sleeve was authorized in 1952. NPSHPC-Jack E. Boucher photo-HFC#58-JB-276 |

The major contribution of the new method of distributing the uniform specifications was that for the first time drawings were included within the regulations, along with the descriptions of the various articles and ensembles. Prior to this the old blue print had been altered in order to accommodate the changes.

Ranger Wilber Doudna, Death Valley National Monument, April 3, 1938. While not covered under the Uniform Regulations, another popular item of apparel out West, especially at Death Valley, was a short leather jacket. These were cut on the pattern of the field jacket, including pleated pockets. It is impossible to determine the color from existing photographs, but an extant example in the NPS History Collection from another park is forest green with plain green buttons. NPSHPC-DEVA 651.531#219 |

The few surviving sheets of Office Order No. 350, along with some memoranda from the official correspondence, enlighten us as to several changes that occurred before it was superceded by a new manual in 1940.

At the 1938 superintendent's conference, it was recommended that an aluminum-colored pith helmet with a large sterling silver Sequoia cone ornament be authorized for park rangers in extremely hot regions. This recommendation was passed, but when Office Order No. 350, revised was issued on April 19, 1939, the color of the helmet was changed to forestry green and there was no mention of an ornament.

This was cleared up in a memorandum from Acting Director Demaray on July 27, 1939. "It was found that aluminum colored helmets could not be purchased and no satisfactory sequoia cone has been devised for use on the helmet," he stated. "Consequently the color of the helmet was changed to forestry green and the cone ornament eliminated."

On September 3, 1938, the regulations were amended to include tropical worsted as an acceptable shirting material for hot weather and again on November 10 a "Forestry green, 1-1/4 inches wide" leather belt with a "nickel-plated buckle" was "prescribed for wear only when the coat is worn." [15] A drawing shows a plain belt with a line tooled all around, approximately 1/8-inch from the edge. It has two retaining loops, or cinches, for the end of the belt. The buckle was a simple open-frame, single loop type.

The above begs two questions. Why, when all leather was to be cordovan, this leather belt was specified to be forest green? And why was the belt "prescribed for wear only when the coat is worn?" Since the belt would not show when the ranger had his coat on, you would think it would be just the opposite. There is no explanation as to either of these issues.

Apparently, others picked up on this enigma as well, since it was corrected by a revision to the regulations in April 19, 1939. The web belt was eliminated and the color of the leather belt was changed to conform to the standard cordovan color of the Park Service leather goods. At the same time, the width of the belt was increased to 1-1/2 inches.

In addition, the regulations contain references to Emergency Conservation Work employees, who since they were under the aegis of the National Park Service had first shown up in the 1936 Uniform Regulations. The new revisions to the 1938 regulations changed their name to read "Civilian Conservation Corps".

Also, under this same revision, a 1/2" chinstrap and a forestry green pith helmet, plus ventilator holes in the hat were added. Even though this is the first time ventilator holes had been specified, they show up in photographs since the early 1930s.

Carlsbad Caverns National Park, Southwestern National Monuments, Petrified Forest National Monument and the Boulder Dam National Recreational Area were included in the list of parks whose employees were authorized to wear trousers in lieu of breeches. [16]

A new "Texas Ranger" style belt was designed in early 1940 as an alternative to the plain belt. This new belt was 1/8-inch thick by 1-1/2-inches wide, embossed with a design similar to the hat band. It was a billeted design, like most western gun holster belts, which utilize a secondary narrow belt, or billet, sewn on top of the wider main belt to secure it. The first company to respond to the new design was the B.B. McGinnis Company, Merced, California, who advertised the belt for $1.00. But Fechheimer Brothers proved to have a superior product and its belt was approved by the Director. Fechheimer originally priced the belt at $1.25, but with it becoming the authorized Service belt and no doubt a substantial order being placed, the cost was reduced to $1.15. [17]

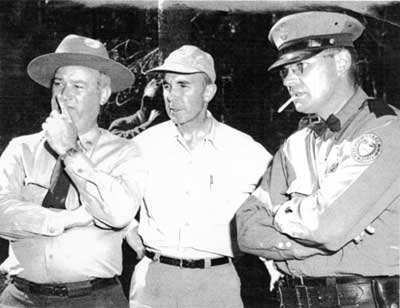

Investigating double murder at Crater Lake [National Park] 7/1952. Wosky is wearing the very popular "billeted" belt. Left to right: John B. Wosky, supt.; Thomas J. Allen, Asst. Director, Operations; unnamed Oregon State Policeman Courtesy of Kettler, Herald & News, Klamath falls, Oregon |

Along with the billeted belt was one authorized for Service employees required to wear side arms. It had a strap that went across the chest and over the shoulder to help support the weight of the weapon. This style belt, known as a Sam Browne, was copied from the British military and used by the U.S. Army, as well as law enforcement agencies. This belt was not embossed. Both belts were cordovan color.

A complete Class A standard National Park Service uniform of 19-oz elastique (made by Weintraub Brothers & Company, Phila.) could be purchased at Pryor Stores concession at Yellowstone in May, 1940, for $63.55. By September 1, 1941, the price had risen to $65.60, less boots (Fechheimer). Boots cost approximately $25.00.

1940 NPS Junior Park Warden badge. Although officially called the "Junior Park Warden" badge, the "Junior" was deleted no doubt because of lack of space on badge. It was made of nickel-plated German-silver like the other badges of this period. Courtesy of Deryl Stone Collection |

With the issuance of the National Park Service uniform regulations in a manual format, uniform regulations became an entity in their own right and were no longer classed under the general heading of "Office Orders". (although the first manual was classified as Office Order No. 350)

On November 22, 1940, a new manual for uniform regulations were issued for the Service. A new badge for "Junior Park Warden" was instituted along with two new uniforms. Due to the extreme heat associated with their location, employees at Death Valley National Monument would now wear the following:

Park Naturalist H. Donald Curry, 1939, Death Valley National Monument. Although Curry is not wearing the prescribed "Sun Helmet" or belt, he does have on the regulation "Sand Tan" shirt and trousers. NPSHPC/DEVA651.531#522 |

"Sun Helmet: Sand tan color [instead of forest green-author [18]] with silver Sequoia ornament.

Shirt: Sand tan color, any acceptable material, cotton gabardine, broadcloth, or twill; collar attached, shoulder straps, two large plaited pockets with buttoned flaps and pencil openings on the left; single button cuffs.

Trousers: San[d] tan color, cotton gabardine, twill, or similar material; tunnel belt loops 2" on sides, 1-1/2" cuffs."

Plus regulation "new style" belt, Blucher type shoes (high-top, lace-up), socks and tie.

It may seem strange to people today that the Service would create a lightweight uniform for hot weather that retained the tie, but at that time it was considered vulgar to expose the top of the chest when meeting the public. Dispensing with the coat was a major concession.

In addition to the hot weather uniform, the regulations also authorized new uniforms for the National Park Service "navy".

The Service had expanded rapidly during the previous decade, in both territory and personnel. The matter of uniforms had become so complicated that at the superintendent's January conference it was recommended "that the whole matter of uniforms for Service personnel be studied by the Uniform Committee and a complete report thereon be submitted to the next conference."

It was further determined that the five man uniform committee was no longer adequate and that the committee should comprise Chief of Operations Hillory A. Tolson from Washington and two superintendents or assistant superintendents from each of the Service's four regions: Lemuel A. Garrison of Hopewell Village National Historic Site and Lawrence C. Hadley of Acadia National Park from Region I; David H. Canfield of Rocky Mountain National Park and Charles J. Smith of Grand Teton National Park from Region II; John S. Mclaughlin of Mesa Verde National Park and Hugh M. Miller of Southwestern National Monuments from Region III; and Earnest P. Leavitt of Crater Lake National Park and Guy Hopping of , Kings Canyon National Park from Region IV. The committee members were to canvas their respective regions and submit recommendations for uniform changes to Uniform Committee Chairman John C. Preston, superintendent at Lassen Volcanic National Park. [19]

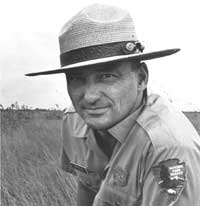

Lemuel A. "Lon" Garrison. This image was taken in 1957 when he was superintendent of Yellowstone National Park. Garrison later became Uniform Committee Chairman before being appointed a Regional Director. Courtesy Haynes, Inc. #57044 |

At the conference there was an element that considered the uniform inappropriate in its present form for a "seashore or maritime site, an historical mansion or some of the recreational demonstration areas." Most, however, thought that the uniform was suitable for all of the National Parks and should not be "tinkered" with. Lemuel Garrison considered the "function of the uniform" to be "two fold--first to provide decent presentable work clothing, and second, to identify the wearer as a Park Service employee. With the far flung range of present Service areas, the visitor who has been to Olympic should be able to recognize immediately the same uniform if worn in the Everglades" and "will recognize that the areas are all under the same administration". [20]

This was a reaffirmation of the original principles upon which Horace Albright and Dusty Lewis had pushed for uniforming the Service.

In 1941, several guide positions were established at Carlsbad Caverns and Mammoth Cave national parks and the uniform committee was requested to consider issuing a "Park Guide" badge for them. Acting Director Hillory A. Tolson felt that since the uniform regulations now covered "badges of similar design for "park ranger", "park warden" and "park guard" . . . we should have a badge with the words "Park Guide"..."

Taking this request under advisement, the uniform committee decided that since the other positions were authorized specific badges for their positions, the guides should have their own badge as well and recommended that the regulations be changed to reflect this. [21]

Even though the above was authorized, there is some doubt as to it ever being implemented. Pearl Harbor may have interrupted the process since there are no known examples of a "Guide Badge" struck in the style of badge then being used.

As the year progressed, there was considerable debate over exactly what changes to the uniform should be made, if any. In addition to the men's uniform question, there was also one concerning women. Fechheimer Brothers Company, Cincinnati, Ohio, had submitted a series of sketches of proposed uniforms for the women in the Park Service. It is not known whether these were requested by the Service or just a bit of entrepreneurship on the part of Fechheimer. Even though women employees in certain positions such as guides and historic aides were wearing a uniform of sorts, the official NPS uniform regulations did not cover these.

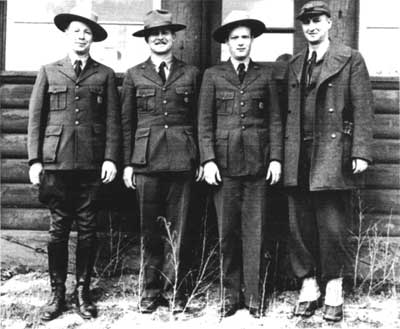

Standard uniforms, 1941. Custodians Lombard, Joyner, Mattes and Superintendent Canfield display their uniforms while attending the First Annual Rocky Mountain National Park Conference. The custodians are wearing the standard dress uniform with either breeches or trousers, while Canfield has on his ski outfit. Left to right: Jess H. Lombard, Fort Laramie National Monument; Newell F. Joyner, Devils Tower National Monument; Merrill J. Mattes, Scotts Bluff National Monument; David H. Canfield, Rocky Mountain National Park NPCHPC-Humberger Photo-ROMO#11-5-1-18 |

Recommendations from the field were many and varied. These suggestions, some of which were very credible, covered just about all aspects of ranger wear. For example: Coat should be less military; there should be special fire fighting clothing; wider use of hat; wider use of cap; lightweight cotton summer uniforms; badges of solid metal, not plated since plating wore off; discontinue using the USNPS collar insignia; embroider "National Park Service" on cloth and sew to coat [sounds familiar]; select an excellent uniform supplier because now when an employee orders a new uniform he usually "gets fits but not a fit." The majority seemed to center on ranger comfort, either material weight (depending on park), or cut. [22]

Unfortunately, the Japanese made all of these suggestions academic at Pearl Harbor. One of the first restrictions brought about by the war was General Conservation Order M-73-a, effective March 30, 1942. This order was implemented "To conserve the supply of wool cloth entering into the production of Men's and Boys' clothing," thereby maintaining an adequate supply of wool for military uniforms. This effected all non-military clothing production.

Upon being informed of this restriction, Uniform Committee Chairman Preston wrote to Fechheimer Brothers, the current uniform supplier asking how this new order would effect the Park Service uniforms and how much uniform material they had on hand.

In his reply, Mr. A. S. Holtman, secretary of Fechheimer, stated that only uniform parts that were made of wool would be effected. Items such as jackets, breeches and trousers were exempt, although the cuffs on the trousers must be eliminated. Coats could not have patch pockets and the backs had to be plain without half-belt, pleats or vent. Coats could not be ordered with two pair of trousers, although they could be ordered with one pair of breeches and one pair of trousers. The belt was the only part of the topcoat effected.

Holtman further stated that at present Fechheimer Brothers had a good supply of Park Service material, but, when that ran out the Service would need to acquire a "Priority" to secure woolen fabrics from the mills. So far "none of the Government Services seem to be able to get this", although he had received "unofficial information" that morning that on "April 5 an amendment might be issued to apply against Order M-73-a, and that it might include uniforms for Police, Firemen and Government Services as essential Defense uniforms." He suggested that the Service apply for this "essential" status.

Uniform. Short jacket & breeches. Dist. Ranger Harold Ratcliff, 1938. Ratcliff is wearing the uniform, sans hat, prescribed for ranger wear during World War II. NPSHPC-ROMO#11-5-1-8 |

Holtman followed up this letter with another one on March 28, 1942, informing Preston that "any company, group, or service, such as defense plants, police, firemen, etc., who can secure a Priority Certificate of A-10 or better, will not be affected by General Conservation Order M-73-a." [23]

In the meantime, Preston had recommended that in view of the coat restrictions, the ski jacket be adopted as the official uniform coat for the foreseeable future and that hot areas not wear a coat in the summertime. Those with standard coats would still be able to wear them if so desired.

The Directors office concurred with Preston's suggestion that "as soon as possible the Director issue instructions that uniformed personnel entering on duty for the first time, or purchasing new equipment should purchase a fatigue jacket instead of the present regulation blouse or coat". In areas where weather conditions permitted, superintendents could authorize employees to omit wearing of the blouse or jacket, providing all uniformed personnel in each district or at each station are dressed alike.

Another difficulty was in procuring boots. Trousers and shoes, which were easier to obtain, could overcome this. "I do not believe that we as individuals or as an organization should approach the War Production Board regarding priorities on uniform materials as suggested by the Fechheimer Company, Associate Director Tolson wrote. "We can make out adequately with the items available." [24]

Acting upon a memorandum sent out by Tolson on June 26, 1942, suggesting that the uniform committee's study of uniforms be "deferred during the war period", Uniform Committee Chairman Preston thanked the committee for their "genuine interest" in the study and thought that "Following the war the Committee should again become active inasmuch as many new ideas regarding uniforms will develop during the war years." [25]

Ex-FOREST RANGERS SERVE WITH COAST GUARD MUNITIONS DETAILS. Former forest(sic) rangers in national parks, these Coast Guard officers have completed a course in handling, storing and loading of explosives at Washington, D.C, and will be assigned to duty at U.S. ports, where the Coast Guard directs loading of munitions for shipment to the fighting fronts. Left to right: Lieutenants (j.g.) Frank F. Kowski, William A. Nyquist and Wayne B. Alcorn, of YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK; Albert D. Rose, chief boatswain, of MT. RANIER(sic) NATIONAL PARK, and Carl E. Jepson, chief boatswain, of GRAND TETON NATIONAL PARK. Although this image has nothing to do with NPS uniforms, it has been included here to show some of the NPS personnel that did their bit to end World War II so they could get back to the really important things, like "rangering." Courtesy of Public Relations Division, U.S. Coast Guard |

Thus the National Park Service Uniform Committee officially closed shop for the duration, as far as any style changes went. There were still problems to be ironed out that the Committee had to address, such as what type of material would make a satisfactory replacement for that used in making the uniform and where it could be obtained. Different cotton fabrics were checked out, but to no avail.

Another problem arose as to what configuration the "five-year" stars should assume on the sleeve of a ranger attaining twenty-five years' service. The regulations stated: "When more than one star is worn, they shall be arranged horizontally up to four and triangularly when more than four stars are worn." This regulation left a lot of latitude in what was meant by "triangularly". It was finally decided that when five stars were to be used, there would be four across the bottom with the fifth centered above. [26] Subsequent stars would contribute to an expanding pyramid. Stars came in units of one to six. Units of one to four were arranged horizontally, while five and up were to be arranged triangularly. (seven stars were grouped in a unit of three over a unit of four; eight stars were grouped in a unit of three over a unit of five; etc.)

Since the National Park Service apparently was not going to try for a special dispensation from the War Production Board, Fechheimer Brothers did it. In a memorandum dated August 20, 1942, Acting Regional Director Herbert Maier advised Region Four field areas that Fechheimer Brothers had "obtained an A-10 Preference Rating Certificate on National Park Service uniform materials . . . will be able to supply the standard National Park Service uniform without regard to the provisions of Conservation Order M-73-a." He further stated that "The Washington Office does not think it wise to revoke the emergency modifications of the National Park Service Uniform Regulations, but uniformed personnel may purchase and wear the previously standard uniforms so long as they are obtainable." [27]

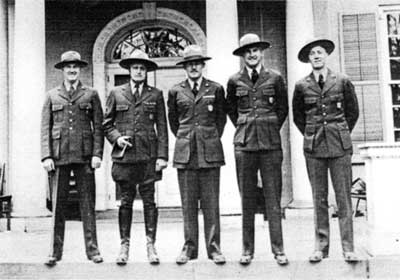

Five rangers at the dedication ceremony of the Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site, April 12, 1946. This image illustrates that the even though the ranger's sleeve brassard went out in the late 1930's, at least two were still being worn as late as 1946. Doust must be mimicking Roosevelt with his cigarette holder. Left to right: Supt. Floyd Taylor; Chief Ranger Harry "Light-horse" Doust; Rangers: Joseph Prentice; Bernie Campbell; [Edwin "Mac" Dale(?)] NPSHPC-HFC#86-208 |

The above is most interesting in light of a memorandum from Acting Director Tolson to the regional directors dated April 1, 1943. In it, Tolson quotes the purchasing officer of the Department of the Interior from a letter of March 20, 1943:

"We have your memorandum of March 3, relative to General Conservation Order M-73 for woolen materials in which you requested that we secure an A-10 priority rating from the War Production Board.

"We have been informally advised by the War Production Board that the National Park Service would be included under item 5 of paragraph (k), which reads as follows:

"'Federal;, State, County, Municipal or local government policemen, guards or militia.' " [28]

If Fechheimer had obtained an A-10 priority as was previously stated, why was Interior still pursuing it in 1943?

After the successful conclusion of the conflict, the National Park Service, along with the rest of the country, was freed from the wartime restrictions. The uniform committee was back in business and as predicted by Preston in 1942, many new ideas had developed during the intervening years.

Among other things, returning uniformed Park Service employees were allowed to wear their military uniforms on duty, along with any decorations, for 60 days. Thereafter they had to don their Park Service uniform but were still authorized to wear "any ribbons to which they are entitled for service in the Army, Navy, Marine Corps or Coast Guard." This allowance was loosely interpreted, because photographs show rangers wearing military medals and decorations, as well as ribbons. This practice continued until rescinded by the 1961 Uniform Regulations.

As soon as possible, the Service instituted a new uniform committee to take up where the old one had left off before the outbreak of hostilities. Among other things, the committee was looking for a new image for the Service.

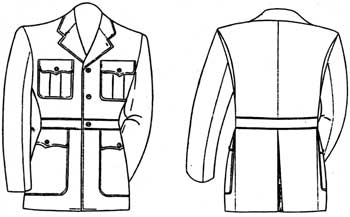

Drawing of 1947 National Park Service ranger coat from the 1947 uniform regulations. The coat now had a full-belted waist with a bellows back like that worn by the Navy flyers of World War II. NPSHC-RG Y55 |

I. J. "Nash" Castro relates that he began his National Park Service career at Grand Canyon National Park in 1939, later becoming junior secretary to Director Newton B. Drury. Having been a naval aviation cadet while attending Lynchburg College in Virginia, it was only natural that he would become a naval flyer when World War II broke out.

After separation from the Navy in 1945, he married and moved to Chicago. At that time, National Park Service Headquarters was located in the "windy city" and since he had previously worked for the bureau and was looking for gainful employment, he paid his old boss a visit.

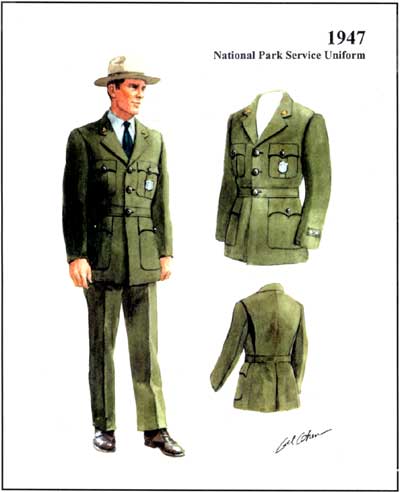

Drawing depicting ranger wearing 1947 pattern uniform with detail of front and back of coat. NPSHC, Gilbert Cohen, artist |

The clothing industry had begun to gear up again for civilian productivity but as yet had not caught up with demand and returning military personnel were allowed to wear their uniforms for 60 days after discharge. So Castro wore his undress Navy greens, or "service" uniform as the Navy termed it, to NPS headquarters and when Director Drury saw him, he became so enamored with the appearance of the coat, he requested that Castro model it for the Uniform Committee. The committee was equally impressed and the new park ranger uniform was styled around this uniform. [29] The National Park Service had returned to the military image, only this time it was the Navy instead of the Army.

When new National Park Service uniform regulations came out on April 11, 1947, what had started as a 4 page typed document in 1920, was now 69 pages long. It was still in manual form, but no longer contained the nice professional drawings and printed text of the 1940 version. Instead, it consisted of line drawings with typed descriptions of the prescribed uniforms, along with instructions about fit; wearing the different uniforms; how to salute the flag; etc., and for the first time uniforms for women appeared in Service regulations.

Louis Schellbach at GRCA, 11/40. This was taken at Grand Canyon National Park and while Schellbach's appearance is typical of the rangers during this period, USNPS collar ornaments were not supposed to be worn on the shirt collar when wearing the coat. NPSHPC-HFC#M69-38 |

L.C. Hadley, park ranger, SHEN [Shenandoah National Park] - 1952 NPSHPC |

|

This comparison of the old and new 1947

uniforms shows many of the changes. Most notable are the lack of

breeches and boots in the new uniform. The new coat is not as form

fitting as the old. | |

Photographs of the various uniforms being modeled made their appearance for the first, and unfortunately the last, time. They were included as part of Amendment No.5 on May 24, 1950.

Fort McHenry National Monument, Interpreting history with children, 1950's. This ranger is wearing the soft cap sans coat that was authorized for hot eastern parks. NPSHPC-WASO-R-681 |

There were a number of changes to the new uniforms, the majority of which effected mainly the standard uniform. The new standard uniform now consisted of:

Hats - The standard hat and cap remained the same, with the sun helmet becoming standard in those areas wearing the new "sun-tan" uniform.

Coat - The coat was now to be belted, with a bellows back and only three buttons; patch pockets (without bellows); two pleated breast pockets; back vent was to extend up to the belt; all outside pockets to have flaps fastened with small Service buttons; similar in style to the naval aviators' working uniform. Coat was to be made from 16 to 22-ounce forestry green elastique cloth, except in hot climates where conditions required a lighter weight uniform for comfort. Then 12-ounce gabardine or tropical worsted cloth could be used. Padding and sleeve lining were to be eliminated in the lighter coats.

Trousers - Trousers were to be of the standard "field cut" as used by officers of the armed forces, without cuffs. Drawing shows them to be the same as previously worn, with the exception of the cuffs and the back pocket flaps being rounded instead of scallop-cut. Materials were to be the same as the coat.

Breeches & boots - Breeches and boots were eliminated as uniform articles with Amendment No. 2 on July 3, 1947. Employees possessing these articles were allowed to wear them "so long as they are serviceable and presentable," but no new ones were to be ordered. (This was not entirely true, rangers that patrolled on horse back still wore these)

Shoes, shirt, tie, overcoat and raincoats remained the same.

The "Death Valley" uniform was now classified as the "sun-tan" uniform and the regional director could authorize it to be worn in "any area administered by the National Park Service in which the summer temperatures are extreme". Each application to wear the special summer uniform was to be scrutinized very carefully by the regional directors to make sure there was sufficient justification. All uniformed employees of a given area were to be uniformly attired. The only change in the regulations governing this uniform was the change of the material name from "sand tan" to "sun-tan." The fatigue and winter sports patrol uniforms remained the same as before.

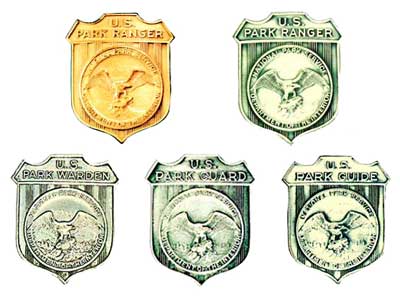

The new regulations included new badges covering everything that had been suggested up until the uniform committee had been disbanded in 1942. These included different badges for: superintendent, assistant superintendent, chief ranger, ranger, park warden, park guard, and park guide. Superintendent and assistant superintendent remained the same, and while the others retained the same design, they were now oxidized silver plated brass, instead of nickel-silver, except for chief ranger, which was gold plated brass. The plating must have been very thin, since all those examined show considerable wear over the high relief.

These five badges were authorized by the 1947 Uniform Regulations. Superintendents and Asst. Superintendents retained the small round badge in gold and nickel-plate, respectively, previously in use. The chief ranger badge was gold plated and the others were silver plated with an oxidized finish. All used brass as the base metal. Left to right: Chief ranger; Ranger; Park Warden; Park Guard; Park Guide NPSHC |

An undated synopsis of the uniform regulations from around this period gives the names and addresses of two uniform manufacturers currently supplying National Park Service uniforms. Fechheimer Brothers Company, Cincinnati, Ohio and B.B. McGinnis Company, 547 Seventeenth Street, Merced, California.

Rangers McLaren and Evans measuring snow pack at Snow Flat at Tioga Pass. Date: 1957. Since there isn't much chance of them meeting visitors, both are wearing a combination of NPS and personal clothing. NPSHPC 68-YOSE-F.652 |

The records also contain another synopsis, dated February 27, 1950, from Shenandoah National Park. It states that heavy high-top leather laced boots were recommended for the fatigue uniform and states "Fatigue uniform trousers may be of canvas or water repellent material in forest green or tan when field conditions make it desirable." It also suggests that Park Rangers have two standard uniforms, one of 13-oz. gabardine for summer and one of 16-oz. elastique for winter. The above changes must have been initiated by Superintendent Edward D. Freeland for Shenandoah's rangers only, since they are not authorized by the 1947 regulations or its amendments.

The 1947 National Park Service uniform regulations were in effect for nine years. Consequently, there were a number of amendments to them, some of which simply concerned clarification of the wording. Others, though, like those below, made small alterations to the regulations themselves.

Amendment No.1 (June 2, 1947) - Overcoat material changed from Elastique to all wool beaver or melton cloth.

Amendment No.4 (January 13, 1950) - Dark green wool could be used for ties, as well as the barathea silk.

Amendment No.5 (May 24, 1950) - Photographs of rangers (including one of a woman) wearing the various uniforms were inserted to show how they should be worn.

Amendment No.6 (June 26, 1950) - Superintendents could now authorize the use of non-visible spring collar clip as a means of improving the appearance of the shirt collar.

Amendment No.7 (June 29, 1952) - New National Park Service arrowhead patch authorized to be worn on all uniform coats, jackets and shirts, "except on raincoat".

Amendment No.8 (September 18, 1953) - The sun helmet is deleted. At the same time 90% Orlon/10% Rayon mixed materials were authorized to be used in place of the previously prescribed forestry green elastique cloth, if such materials in the proper weave and color are available from the uniform manufacturer.

Amendment No.9. (March 24, 1954) - Rangers authorized to wear shirt with collar open when authorized by superintendent.

One of the first arrowhead shoulder patches. Three were issued to each permanent and one to each temporary ranger. Unfortunately, these first patches were not sanforized and could only be worn on the coat. This was corrected on future orders. NPSHC |

Amendment No. 7 was especially significant. A contest had been held in 1949 in an attempt to come up with a symbol for the National Park Service. Even though the winning design was never used (see Book No. 1, Badges and Insignia), the idea of using a tree and the arrowhead was brought forth. After much refinement, the Arrowhead became the official emblem of the National Park Service on July 20, 1951. It was first used the following year in static situations, such as folders and park signs. Then on June 29, 1952, with the above amendment, it began to be used on uniform coats. It has graced the ranger's uniform ever since.

Rangering was, and still is, a vocation, not a job. Rangers worked long hours for low pay, from which they had to buy their uniforms. This was alleviated, somewhat on September 1, 1954, when the Federal Employees Uniform Allowance Act (Public Law 763) was approved, authorizing a clothing allowance for federal employees that were required to wear a uniform. Uniformed members of the National Park Service began receiving their clothing allowance for the first time on May 3, 1955, under FAO-19-55. The allowance was computed at $0.274 for each day the individual was employed, or $25.00 per quarter, for a maximum of $100.00 per year. [30]

In 1956, the National Park Service revised its entire format for uniform regulations. Uniform Regulations were no longer a separate entity, but were now Part 160 of the National Park Service Administrative Manual. These new regulations went into effect on September 11, superceding all of the previous regulations. Specifications were back to text only, with the drawings and photographs utilized in previous editions eliminated.

These regulations remained basically the same as previously in effect, although there were a couple of minor changes. Amendment No.1 of the 1947 was incorporated giving employees their choice of having their overcoat made of either all-wool beaver or melton cloth instead of elastique. As in the past, anyone having the elastique overcoat could wear it as long as it was presentable and serviceable. The fatigue uniform now became a "field" uniform with the option of having a single or a double layer back. With single back, yoke effect did not appear on front.

At the same time, chief park naturalists, historians, and archaeologists were authorized to wear the same gold badge as used by chief rangers.

One of the six-star Length-of-Service panels suggested by Charles C. Sharp. NPSHC |

The length-of-service insignia was further refined. Until now, the service stars had been embroidered on a continuous roll, same as the stripes. When cut and applied to the sleeve, the serge material often unraveled and took on a ragged appearance if not sewn properly. Charles C. Sharp suggested that the stars be made up on neat cloth panels of from one to six each with a border around them, like the arrowhead patch. This suggestion was incorporated in the new regs. In addition because of the long service of some personnel, it was decided that when seven stars were worn, the bottom row would contain five, instead of the customary four.

On March 20, 1957, Amendment No.3 authorized the use of 12-ounce Dacron-wool material for summer uniforms, as well as a new cap for the Winter Patrol Uniform. The new cap, similar to a hat bearing the "North King" trade name, was for wear in areas of extreme cold. This cap was fur lined in a "beaver brown" color with adjustable earflaps and embroidered NPS insignia on the front. The standard ski cap was retained for use in less extreme areas.

Badges were to be worn on the pocket flap of the shirt when a coat was not worn. Amendment No.5 (May 9, 1958) changed this location to above the pocket. Unfortunately, the badge proved to be too heavy for the lightweight material used for the shirts, so the design of the shirts was changed to incorporate a reinforcement above the pocket to accommodate the badge. Old style shirts could be worn until the following June 1, creating a situation where badges were being worn on shirts in two different locations, even in the same park.

Apparently the incorporation of the uniform regulations in the NPS Administrative Manual was not satisfactory, because in 1959 a new format was inaugurated. On December 2 the National Park Service Uniforms Handbook was issued. It was to become fully effective on January 1, 1961. The new regulations not only gave the regulations (when, what and how to wear) and specifications for uniform dress, but a somewhat abbreviated history of National Park Service Uniforms; definitions of terms; hints on the care and maintenance of uniforms (use clear nail polish to retard buttons from tarnishing); posture (protruding stomachs and slumped shoulders constitute being out of uniform); list of current uniform suppliers; etc.

Conrad Louis Wirth, Director, National Park Service, 1951-1964 NPSHPC-Abbie Rowe photo-HFC#1960A |

The Regulations and Specifications section begin with a message from Director Conrad L. Wirth. This set the tone for the in-depth detail of the following instructions.

"Despite the excellent appearance our uniformed force makes at many areas, there does exist a casual attitude about the wearing of the National Park Service uniform at many other areas. We find people (including superintendents) who should be in uniform not wearing the uniform. We find others not wearing the proper uniform, or wearing it carelessly. We find them worn with ornaments, tie pins, and various unauthorized lapel buttons or other insignia. We have said very little about this in the past, but now we are beginning to get criticism from people outside the Service.

"It is time to correct the uniform situation throughout the Service, and to follow through and see that it stays corrected. The uniform identifies us. It can and should be worn proudly and, now that annual uniform allowances help bear the costs, added emphasis should be given to wearing it properly.

"I wish to point out that it is the responsibility of the superintendents to scrutinize the uniform of each individual to see that every detail is correct in accordance with regulations; that it is worn when required; and that it is worn properly, without unauthorized additions or decorations. Superintendents have authority to decide when the uniform dress coat shall be worn.

"We realize there will be problems, nevertheless we are expecting superintendents to meet the situation and emphasize it by individual inspections and comments. The wearing of the uniform is an official--not a personal matter. Regional directors will observe the situation at each area and assist when necessary. I feel certain of your complete cooperation."

Ranger with hikers along trail of Mt. Le Conte, Great Smoky Mts NP, 1960. Ranger is wearing his badge on his shirt above his left pocket. He is also wearing the pith helmet although it had been eliminated from the regulations on September 18, 1953. NPSHPC-Jack Boucher photo-HFC#C60-JB-387 |

The manual goes on to denote responsibilities and various methods to achieve uniformed employee compliance to the regulations.

The history section ends with "In the words of former Superintendent Frank Pinkley, "The National Park service Uniform can and does build morale in the man who wears it, and prestige in the eyes of the public--when it is worn by the right man."

Some of the definitions in the new manual are interesting.

Standard was no longer used since all uniforms authorized were standard for the circumstances.

Uniform denoted only men's uniform. Women's uniforms were described seperately.

Dirty-Work Clothing meant no prescribed uniform. Civilian clothing devoid of any official NPS garments or accessories that would identify wearer as a park employee was to be worn when doing dirty or messy work, including small fire suppression duty. (The work uniform was to worn when fighting large fires, where NPS recognition was desired.)

This last one is especially fascinating. It would seem the Service didn't want the public to know the rangers got their hands dirty.

Since the employees purchased their own clothing, the handbook went into great detail as to the style and material of the various uniform articles. Suppliers were required to attach a "guarantee label" on the clothing and equipment they furnished to Service personnel, certifying that the article met NPS standards. Another innovation was the mention in the specifications of various suppliers names whose uniform articles were judged to set the standard.

The "handbook" brought with it a number of changes and a few new articles of clothing. The hat remained the same, except that now the "dents" were being blocked in at the factory. This made for a more uniform appearance. In addition, a new straw hat was added to be worn with the summer uniform in extreme heat or very hot and humid climates. The life expectancy of the straw hat was one or at the most two years. A transparent plastic hat-covering (similar to Eldon Rain Hat Protector No. 3000) for protecting both styles of hat was included.

Roger Allen, superintendent, Everglades National Park, 1967. Allen is wearing the standard ranger straw hat with the pine cone version of the hatband. NPSHPC-HFC#91-5 |

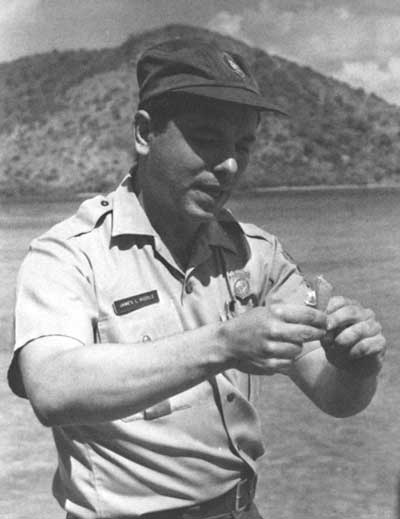

Ranger James E. Putman and a friendly opposum, c.1968. Putman is wearing the rain cover for his hat. He is also wearing the 1960 nametag and 1968 badge. NPSHPC-HFC#96-1347 |

Although neither the regulations or previous amendments address it, the dress cap was not included in the 1961 regulations. Apparently the straw hat superceded it.

The fur hat for extreme cold areas was changed from brand name "North King" to "Alaska Cap". (Eddie Bauer, Seattle, Washington, or its equal) The new cap was specified to be "Forestry green with beaver mouton fur [31] trim, down insulated. Mouton fur trim to turn down to protect neck and ears. Concealed drawstring to provide exact adjustment of head size."

The coat, while appearing to be the same, had several changes as well. A badge holder (two silk corded loops 3/8" wide, sewed to left breast pocket pleat, 1-1/4" apart, lower loop 2" from bottom of pocket) were sewn to the left breast pocket pleat. The pockets now had three pointed flaps (earlier flaps were rounded on outside corners) and the top pocket flaps were stitched down all around so pockets could not be used. All buttons were to be removable, fastened with bodkin, [32] ring or similar device.

Trousers remained the same with the exception of the back pocket flaps having concealed buttons. (no stitching was to show on flap)

A new "embossed" belt was specified for uniformed personnel. Unofficially, it was felt the billeted belts accented "ranger pots" and the new style cut a "trimmer" figure. The new belt remained 1-1/2 inches wide, but now the buckle was the full width of the belt and the "USNPS" was eliminated. This, with minor alterations remains the same belt used today.

Embossed leather belt, 1961. Color, cordovan. NPSHC-HFC RG Y55-1961 Uniform Regulations |

Overshoes were added to the dress uniform. They could be either plain black rubbers or plain black galoshes type with four buckles or zipper.

The white shirt was eliminated as part of the dress uniform. All shirts would now be gray. A reinforcement was added above the left pocket to accommodate the badge. Three different styles of pocket flaps were authorized with a pencil pocket in left pocket. (Lavigne, Miami, Florida - #950ff or #950jr (short sleeves) A crease resistant, nylon fortified rayon, topical weave shirt was optional for wear with dress uniform when coat was not worn. (B.B. McGinnis)

Official four-in-hand necktie was now dark green (Wembleytown shade 3Z61 or equal) worsted wool, 3 inches wide at widest point. It is interesting to note that even though the regulations specify a "four-in-hand" tie, in Care and Maintenance they suggest using a Windsor knot.

A new waterproof raincoat with optional rain leggings was introduced. Both were made of forest green nylon fabric with Butyral [33] (or equal) covering on inside. Coat was a 3-button fly-front design (buttons do not show) with raglan [34] shoulders, slash pockets cut through and a one-piece detachable outer jacket with set-in sleeves and badge holder. (Jacket resembles a cape with sleeves) Leggings were without cuffs but with straps and loops for attaching to trouser belt. Both came with their own carrying case.

The overcoat and trench coat were replaced by a storm coat. This coat resembled the trench coat in design with a cape attached to the back. But instead of waterproof gabardine, the new coat was constructed of Zelan treated forest green nylon canvas. For warmth, a removable all-wool liner was attached to the inside by means of a Talon zipper. Coat also had a badge holder attached to the center of the left breast.

Plain cordovan-colored leather gloves or mittens were now optional wear. They had to be "without conspicuous ornamentation, buckles, or fancy stitching."

Unlike the dress uniform, the field uniform was to be worn where public contact was secondary, but where ready identification of the wearer as a National Park Service officer was necessary. It was designed to achieve uniformity, as well as withstand hard usage with the greatest degree of comfort possible, yet retain the advantage of quick identification of the wearer.

Camp Schurman Dedication 8-18-63. Butler is wearing quilted jacket and field cap with the applied USNPS patch. Left to right: Rev. Victor McKee; John Simac, Protection Assistant; William J. Butler, Gorder Rasmussen NPSHPC-HFC#99-1 |

In situations where no public contact was likely and the work was of an extremely dirty nature, or of a character in which identification was not desirable, the employee was to remove their uniform and wear completely nonuniform garments. Worn out or frayed items, no longer serviceable for uniform wear, could be worn for dirty-work clothes as long as they were devoid of any National Park Service identification. But items readily identifiable with the NPS, such as the hat (felt or straw), even though unserviceable, could not be worn.

Frank [F.] Kowski, Director, Yosemite Training School, Yosemite National Park [now Albright Training Center, Grand Canyon National Park], 1960. Kowski is wearing the new green laminate nametag along with the older [1946-1960] badge. NPSHPC-Jack E. Boucher photo-YOSE#60-1172 |

Field uniforms were to be worn for assignments requiring rough work, such as back country or inner canyon patrol, hiking, rescues, horseback trips, research, fish planting, boundary, hunting season, or boat patrol, as well as supervisory fire fighting duties.

Uniformed employees now had two field jackets from which to choose. A lightweight (8.5-oz. twist twill cotton suiting - J.P. Stevens, style 2955 or D.S. Lavigne, No.4506) "Eisenhower" [35] style or a heavier (16 oz. orlon whipcord) one for colder weather. Both jackets had two patch pockets with button-down flaps (no pleats). The "Eisenhower" jacket had two buttons on belt for size adjusting.

The corresponding trousers were made from the same forest green material as the coats. They were without cuffs and had slit rear pockets. (no flaps) Trousers now began utilizing zipper flys.

Footwear became more liberal. Cordovan colored oxfords, or shoes; or work shoes, boots or hiking boots of any reasonable type, as the occasion demanded, could be worn. Cordovan or dark brown cowboy boots of conservative design were also authorized for horseback patrols.

In addition, any of the items pertaining to the dress uniform (overcoat, overshoes, gloves, etc.) could be worn as the situation dictated. Any of the parkas from the Winter Activities Uniform could also be worn when authorized by the superintendent.

Uniformed employees in parks with well established snow seasons, which attracted large numbers of visitors, performed duties involving public contact as a primary function in connection with patrolling ski slopes. Inspecting lifts, rendering first aid, transporting injured on ski slopes, as well as giving information, parking cars, directing traffic, etc. Specialized garments prescribed for wear by uniformed employees assigned to such duties had to be carefully considered to achieve uniformity in appearance, comfort, practicality, as well as availability at a reasonable cost.

The Winter Activities Uniform was to be used when made appropriate by weather conditions where public contact duties were an important element of the assignment, regardless of whether skiing is a part of the activities. On long cross-country ski trips when public contact was not a factor, the uniform was not required to be worn. Shirt, tie, and other garments regularly worn under the parka were optional. Style and material of ski trousers were optional as long as they were forest green to match the cap and parks.

Irwin Wente, maintenance, Everglades National Park, 1969. Wente is wearing the service cap with the inline white USNPS cap patch. NPSHPC-HFC#69-308-80 |

The cap was changed to a cotton and nylon pima, same material as parka. It had a 2-1/2 inch visor and a two piece top that fit the head snugly. For cold weather it could be ordered with cotton flannel lined flaps that turned up inside the hat when not used. There were to be no buttons, bows or other nonfunctional decorations on cap. USNPS in 3/4 inch gold letters was embroidered on the front above visor. Prior to the regulations becoming effective, Amendment No.1 July 13, 1960, changed the color of the letters from gold to silver (white) in order to conform to the color of the other ornamentation used on the uniform.

The ski parka was to be made from a moisture repellent processed (Zelon or equal) cotton pima [36] blend forestry green material. The unlined body was skirted (approximately coat length) with a waist drawstring. A full hood was permanently attached inside the collar with drawstring face opening and snaps at the throat. Elastic sleeve wrists provided a snug fit. Two zippered slash pockets were on the breast and a 9 inch zippered opening on each side of the double thickness back formed a large pocket or compartment extending down to the drawstring. Material, style and color was to conform to U.S. Forest Service specifications as manufactured by Sports Caster.