|

Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park Georgia |

|

NPS photo | |

A Mississippian Outpost on the Macon Plateau

From Ice Age hunters to Creek Indians of historic time, Ocmulgee testifies to 10,000 years of people living in this corner of North America. One period stands out. Between 900 and 1100 CE (Common Era) a skillful farming people lived here. Known as Mississippians they were part of a distinctive culture that crystallized about 750 in the middle Mississippi Valley, spreading over the next 700 years along riverways throughout the central and eastern United States. The Mississippians brought a more complex way of life to the region. Although far removed from such Mississippian centers as Cahokia in Illinois and Moundville in Alabama, the people here were heirs of an important culture and enjoyed a life as successful as any north of Mexico.

Mississippians at Ocmulgee were intruders of a sort. They apparently displaced Woodland Indians, although there is no evidence of conflict. The newcomers were sedentary and lived by farming bottomlands for crops of corn, beans, squash, pumpkins, and tobacco. They built a compact town of thatched huts on the bluff overlooking the river. At one time more than a thousand persons lived here. For public ceremonies they leveled an area near the river and built a series of earth mounds—places important in their religion and politics. They did not build the mounds to full height all at once but raised them over the years, perhaps as new leaders came to power or in response to cycles about which we can only speculate.

Earthlodges were also central to life, and there were several at Ocmulgee. The best preserved earthlodge has been reconstructed; it is 42 feet in diameter. Opposite the entrance is a clay platform shaped like a large bird. There are three seats on the platform and 47 on the bench around the wall. In the center of the lodge is a firepit. This building may have been either a winter temple or a year-round council house. The 50 or so persons who met here were probably the group's leaders.

The mound on the town's west side is a burial site. Like the temple mounds the Funeral Mound was flat-topped, with steps leading up the side to some kind of mortuary building. More than 100 burials have been found here. Some contained elaborate shell and copper ornaments suggesting high status, but most burials had no offerings.

Mississippians seem to have influenced the surrounding population (mound-building, rudimentary farming), but we don't yet know how they interacted. Nor do we know why the town declined or what happened to the inhabitants—whether they died out, migrated elsewhere, or were assimilated. Whatever their fate, by 1100 Ocmulgee was no longer a thriving outpost of Mississippian culture. Over the next two centuries other Indians occasionally used the old townsite. In the 1300s a new culture arose and spread widely through the Southeast. Known as the Lamar culture they appear to have been a blend of Mississippian and Woodland elements. The Lamar were farmers, skilled hunters, and mound-builders. Their distinctive pottery employed designs characteristic of their Woodland and Mississippian predecessors. They also used the old town site, then fallen into ruins. One of their major centers was the Lamar site, several miles away in the swamps along the Ocmulgee River. This village contained two temple mounds and was surrounded by a stockade. It was the Lamar people that Hernando de Soto encountered in 1540 on the first European expedition into this region.

For natives the arrival of Europeans was catastrophic. Disease caused staggering losses. Indians were drawn into the newcomer's trading world and political disputes, which changed forever their traditional way of life. The English set up a trading post at Ocmulgee around 1690, and many Creeks settled here. Within a century there were few vestiges of Mississippian life anywhere and virtually no understanding of the culture. When naturalist William Bartram saw Ocmulgee in the 1770s, he wrote with respect mingled with incomprehension of "the wonderful remains of the power and grandeur of the ancients in this part of America."

Sequence of Cultures on the Macon Plateau

Paleo-Indian

Pre-9000 BCE (Before Common Era)

The first to live in this region were nomadic Indians who hunted large

mammals. These natives were one of the earliest stages of human culture

in North America. A distinctive spear point called Clovis is evidence of

Paleo-Indians here.

Archaic

9000-1000 BCE

Indians of this period were hunters and gatherers who exploited food

sources such as small game, shellfish, and seasonal plants. The atlatl,

a device for propelling spears, came into wide use. Red ochre in burials

suggests the beginnings of ritualism.

Woodland

1000 BCE-900 CE

Cultivating squash, gourds, beans, and corn, Woodland Indians began to

live in villages at least part of the year. Tools and pottery became

more varied. They decorated pottery by stamping the unfired surface with

wooden paddles carved with complex designs. These people were displaced

by the Mississippians but continued to live in the area.

Early Mississippians

900-1100

These people originated in the Mississippi Valley. They planted

extensive crops and lived in large villages with intricate social

relationships as suggested by their earthlodges and flat-topped mounds.

Their pottery was plain but of varied sizes and shapes.

Late Mississippian

Post-1350

After the waning of the Mississippians a new way of life sprang up that

combined elements of the two previous cultures. This culture is called

Lamar after the site at which it was first described by archeologists.

Now a unit of Ocmulgee National Monument this palisaded town had two

temple mounds, one with a unique spiral ramp to the top. The pottery was

decorated with both stamped and incised designs. It was villages of this

type that Hernando de Soto encountered in 1540.

Historic

c.1690-1715

Creek Indians built a large town here to take advantage of commerce with

the British. The village was abandoned after the Indians were defeated

by colonists in the Yamassee war.

Touring the Park

Great Temple Mound rises 55 feet from a base about 300 by 270 feet. Lesser Temple Mound is similar in form but smaller. Little is known about the relationship between the two mounds.

The visitor center houses a major archeological museum. Exhibits describe the human habitation of the area from 10,000 BCE to the early 1700s. Emphasis is on the Mississippian town that flourished here from 900 to 1100.

The visitor center and museum are accessible for visitors in wheelchairs. The film. Mysteries of the Mounds, is captioned. A braille brochure is available.

Funeral Mound once stood almost 25 feet high with deep pits extending more than eight feet below ground level. The mound was built in at least seven stages. The profile across the north face reveals the basic structure that archeologists found in the 1930s. The mound's profile was partially destroyed in the 1870s. About seven feet of material was removed from the top, including portions of stages 4, 5, 6, and 7.

About Your Visit

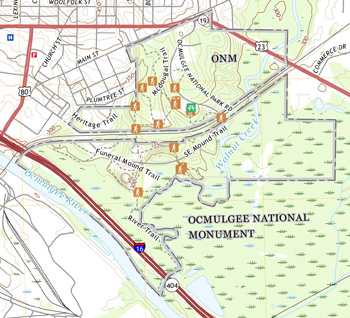

(click for larger maps) |

Ocmulgee National Monument is on the eastern edge of Macon, Ga., on U.S. 80 East. From I-75 exit at I-16 East. Take either the first or second exit from I-16 and follow U.S. 80 East one mile to the park. The Lamar Unit is in the swamps three miles south of Macon. It is open on a limited basis. For information ask at the visitor center or visit our website.

The park is open daily except December 25 and January 1, from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. There is a picnic area. The closest camping area is eight miles away, west of Macon.

Spring and fall are the best seasons for a walking tour of the park. A trail connects most features; seven are described on the right. If the weather is hot or rainy you may want to take the park road around to the large mounds. An interesting walk is along the Opelofa Trail, which takes off from the main walking trail and winds through the Walnut Creek wetlands.

Earthlodge This is a reconstruction of a ceremonial building that stood on the north side of the Mississippian village. It was probably a meeting place for the town's political and religious leaders. The original clay floor is about 1,000 years old.

Village Site During Mississippian times (900-1100) many other structures stood here along with the earthlodge. Among them were several flat-topped mounds, a burial mound, and homes.

Cornfield Mound This mound was originally about eight feet high. Beneath it archeologists found signs of a cultivated field, which is something of a puzzle because Mississippian agricultural fields usually lay in bottomlands. The mound itself was probably a platform for a ceremonial building.

Prehistoric Trenches Two lines of ditches varying in width and depth have been traced around the east side of the village. Some sections are parallel and lined with clay. The ditches may have been borrow pits—sources of fill for constructing mounds.

Trading Post Site English traders from Charleston, S.C., eager to do business with the Creek Indians, built the first trading post on this site about 1690. They traded firearms, cloth, and trinkets for deerskins and furs. Excavations have turned up many goods, including axes, clay pipes, beads, knives, swords, bullets, flints, pistols, and muskets.

Great and Lesser Temple Mounds Relatively little is known about these mounds except that they were topped by rectangular wooden structures probably used for important religious ceremonies. Great Temple Mound is the largest Mississippian mound on the Macon Plateau. Lesser Temple Mound was partly destroyed by railroad construction in the 1830s.

Funeral Mound Village leaders were buried in this mound. More than 100 burials have been uncovered, many with shell and copper ornaments. Like the temple mounds, this mound was built in successive stages. The structures that stood on top at each stage may have been used in preparing the dead for burial. The present height corresponds to the third stage. Much of the mound was destroyed by a railroad cut in the 1870s.

Source: NPS Brochure (2013)

Documents

A Baseline Vascular Plant Survey for Ocmulgee National Monument, Bibb County, Macon, Georgia (Wendy B. Zomlefer, David E. Giannasi, John B. Nelson and L.L. Gaddy, extract from Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2013)

A Preliminary Report on Archeological Explorations at Macon, Ga. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 119 — Anthropological Papers No. 1 (A.R. Kelly, Smithsonian Institutions, 1938)

Amphibian Community Monitoring at Ocmulgee National Monument, 2011 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2013/530 (Briana D. Smrekar, Michael W. Byrne, Marylou N. Moore and Aaron T. Pressnell, August 2013)

An Administrative History: Ocmulgee National Monument (Alan Marsh, 1986)

An Archeological Overview and Assessment of the Lamar Mounds Unit of Ocmulgee National Monument, Macon, Georgia (David M. Brewer and Susan Hammersten, October 1991)

Anuran Community Monitoring at Ocmulgee National Monument: 2014 Data Summary NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2015/983 (Briana D. Smrekar and Michael W. Byrne, October 2015)

Archeology of the Funeral Mound, Ocmulgee National Monument Archeological Research Series No. 3 (Charles H. Fairbanks, 1956)

Cultural Landscape Report: Ocmulgee National Monument (Beth J. Wheeler, August 2007)

Ethnographic Overview and Assessment of Ocmulgee National Monument (Deborah Andrews, September 2014)

Foundation Document, Ocmulgee National Monument, Georgia (October 2014)

Foundation Document Overview, Ocmulgee National Monument, Georgia (November 2014)

Geologic Map of Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park, Georgia (January 2022)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report: Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR-2022/2464 (Trista Thornberry-Ehrlich, September 2022)

Historic Resource Study: Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park (WLA Studio and New South Associates, February 2021)

Historic Structure Report: Dunlap House, Ocmulgee National Monument (Tommy H. Jones and Steven Bare, March 2011)

Historic Structure Report: The Earth Lodge, Ocmulgee National Monument (August 2005)

Historic Structure Report: Visitor Center, Ocmulgee National Monument (Joseph K. Oppermann, December 2008)

Junior Ranger, Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park (2021; for reference purposes only)

Landbird Community Monitoring at Ocmulgee National Monument, 2009 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRDS—2011/305 (Michael W. Byrne, Joseph C. DeVivo and Jennifer R. Asper, Brent A. Blankley, September 2011)

Landbird Community Monitoring at Ocmulgee National Monument: 2011 Data Summary NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2016/1020 (Elizabeth A. Kurimo-Beechuk and Michael W. Byrne, May 2016)

Landbird Community Monitoring at Ocmulgee National Monument: 2014 Data Summary NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2016/1014 (Michael W. Byrne and Elizabeth A. Kurimo-Beechuk, March 2016)

Master Plan and Interpretive Prospectus, Ocmulgee National Monument (June 1972)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Ocmulgee National Monument (Jennifer D. Brown, January 31, 1996)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Ocmulgee National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRR-2017/1521 (JoAnn M. Burkholder, Elle H. Allen, Carol A. Kinder and Stacie Flood, September 2017)

Ocmulgee Archeology: A Chronology (John W. Walker, September 1989)

Ocmulgee River Corridor Special Resource Study (2023)

Ocmulgee River Corridor Special Resource Study: Cultural and Historic Context Report (January 2021)

Ocmulgee River Corridor Special Resource Study: Environmental Context Report (January 2021)

Ocmulgee: The Making of a Monument (Alan Marsh, extract from Proceedings and Papers of the Georgia Association of Historians, Vol. 7, 1986)

Results of Bat Inventories at Ocmulgee National Monument and Proposed Expansion Area 2015-2016 (Steven Castleberry, 2017)

State of the Park Report, Ocmulgee National Monument, Georgia State of the Park Series No. 11 (2014)

Superintendent's Annual Report: 1939 • 1983 • 1984 • 1985 • 1986 • 1987 • 1988 • 1990 • 1991 • 1992 • 1993 • 1997 • 1998 • 1999 • 2000 • 2001 • 2002 • 2003 • 2004 • 2005

Terrestrial Vegetation Monitoring at Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park: 2021 Data Summary NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS-2023/1394 (M. Forbes Boyle, July 2023)

Vegetation Community Monitoring at Ocmulgee National Monument, 2011 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2014/702 (Sarah Corbett Heath and Michael W. Byrne, September 2014)

Vegetation Mapping at Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park: Photointerpretation Key and Final Vegetation Map NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRR—2019/2018 (David L. Cotten, Brandon P. Adams, Nancy K. O’Hare, Christopher S. Cooper, Sergio Bernardes, Thomas R. Jordan and Marguerite Madden, October 2019)

Wadeable Stream Habitat Monitoring at Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park: 2017 Baseline Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRR—2019/2053 (Christopher S. Cooper, Jacob M. McDonald and Eric N. Starkey, December 2019)

Wadeable Stream Habitat Monitoring at Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park: 2019 Change Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRR—2020/2200 (Jacob M. Bateman McDonald, December 2020)

Wadeable Stream Suitability Assessment for Long-Term Monitoring: Ocmulgee National Monument NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2019/1221 (Jacob M. McDonald and Eric N. Starkey, April 2019)

ocmu/index.htm

Last Updated: 25-Feb-2025