|

OLYMPIC

Historic Resource Study |

|

I. UNKNOWN NO LONGER: EXPLORATION

Early European Coastal Exploration

The earliest exploration of America's western coast was accomplished from the decks of ships. For three centuries the great naval powers of western Europe were intent on locating the fabled waterway—a northwest passage—that would lead to the much sought after riches of the Orient. It was this desire to discover the so-called Strait of Anian that motivated Spain, and then England, to send out their most competent naval pilots to search for the illusive passageway in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The belief in the existence of the Strait of Anian eventually led to European exploration of the waters around the Olympic Peninsula.

Spain ushered in the era of northwest coast exploration. In 1543, fifty-one years after Columbus' discovery of the New World, Bartolome Ferrelo and Juan Cabrillo proceeded north up the California coast to southern Oregon to a point west of the mouth of the Umpqua River. Sailing under the English flag, Francis Drake, in the Golden Hind, followed Ferrelo in 1579 and cruised along the coast, possibly as far north as Cape Blanco on the southern Oregon coast. Although Drake is considered by some to have been the first to approach the Oregon Territory, neither he nor his two predecessors are believed to have sailed north of latitude 43° near present-day Port Orford Oregon. Navigating in the winter waters of the Pacific Ocean in 1603, Spanish explorer Martin Auguilar reported reaching Cape Blanco at latitude 43° when the ill health of his crew deterred him from following the coast further north (Bancroft 1884, 137-47; Wood 1968, 66). The Strait of Anian continued as a fantasy in the mariner mind of the 1500s and early 1600s. The Oregon Territory, then including the Olympic Peninsula, remained undiscovered.

According to some sources, Juan de Fuca was another early European explorer who set out in search of the fabled Strait of Anian. Historians disagree about the authenticity of Juan de Fuca's discovery of the strait that now bears his name. According to those who support his claim, de Fuca (born in Greece with the name Apostolos Valerianos) was sent by the Viceroy of Mexico in 1592 to search for the Straits of Anian. Between 47° and 48° latitude (roughly between present-day Grays Harbor and the Quillayute Needles on the Olympic Peninsula), de Fuca claimed he found "a broad inlet of sea into which he entered, sailing therein more than twenty days . . ." (Lauridson and Smith 1937, 3). James Swan, early resident and prolific recorder of Peninsula history during the second half of the 1800s, contended that his own knowledge of the coastline and inland waterways supported Juan de Fuca's general geographical descriptions of features in the area (Lauridson and Smith 1937, 4-5). Nearly two hundred years later, English Captain John Meares credited Juan de Fuca with the first discovery of the strait in describing his own voyage to the Northwest coast in 1788 (Meares 1790, 155).

Within the last 100 years the trend has been to dismiss Juan de Fuca's voyage as pure fiction and folly. Well-known Northwest historian Hubert Howe Bancroft, writing in the late 1800s, strongly refuted de Fuca's claim since his trip was vaguely recorded only by a secondhand informant, and not until 1625 (Bancroft 1884, 74). More contemporary writers perpetuated this attitude of doubt about the validity of Juan de Fuca's voyage (Morgan 1955, 8; Anderson 1960, 76-77).

While the reality of Juan de Fuca's voyage along the north coast of the Olympic Peninsula may be doubted, the reports of his trip had great influence on later explorers and geographers. Voyagers exploring the Pacific Northwest were prompted to search for de Fuca's inland passage. And more than two centuries ago, cartographers drawing maps of this little known region of the world gave permanence to the name of the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Other voyagers, contemporaries of Juan de Fuca, laid claim to the discovery of the Northwest Passage. In 1588 Captain Lorenzo Ferrer de Maldonado claimed not only discovery of this inland waterway, but passage through it, traveling from east to west. Admiral Pedro Bartolome de Fone described the same strait as a river when he visited it in 1640. Neither of these claims are known factual (Morgan 1955, 8-9).

While Spain sent its marine explorers up the coast from Mexico in search of the Northwest Passage, Russian nautical expeditions pushed down the north Pacific coast and the Aleutian Islands in pursuit of fur. As sea otter herds were depleted, Siberian hunters advanced eastward during the early and mid 1700s through the Aleutian chain and across the Bering Strait to the Alaska mainland and down the Northwest coast. Uneasy about Russia's opening of the Strait of Juan de Fuca in either 1774 or 1775. Spanish map makers honored this supposed discovery of the westernmost tip of the contiguous United States by naming it Punta de Martinez (Kohl 1860, 269, 273; Howay 1911, 3-4; Anderson 1960, 80). The opening of the Strait of Juan de Fuca may have been sighted again a decade later, in 1786, by Captain J. F. de la Perouse. Sailing under the French flag, he was engaged in conducting an elaborate investigation of the potential for trade in the Pacific Northwest (Kohl 1860, 273; Pethick 1976, 101-105).

While Spanish exploration moved up the coast from the south and the Russians continued to navigate in ocean waters to the north, the English began exploring the waters and shorelines of the north Olympic Peninsula, the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Puget Sound and Vancouver Island in the late 1770s. Sailing along the Washington coast in 1778, Captain James Cook, making his third voyage in His Majesty's Ships Resolution and Discovery, was in search of the fabled Northwest Passage, when he observed a reef of rocks at "a small opening which flattered us with hopes of finding an harbour" (Howay 1911, 2). Thus, the Olympic Peninsula's westernmost projection of land obtained the name Cape Flattery. (Cape Flattery is thought to have been in use longer than any other name on a Washington map (Hitchman 1959, 7)). A violent storm kept Cook from discovering whether, in fact, this opening was to the legendary passageway reported by Juan de Fuca two centuries earlier (Kohl 1860, 267).

Less than ten years later, in 1787, Captain Charles William Barkley (sometimes spelled Berkeley or Barclay) commanded the fur trading vessel, the Imperial Eagle, when he made positive identification of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Francis Hornby Barkley, Captain Barkley's wife, is believed to have been the first woman to visit this part of the Northwest coast (Howay 1911, 6) and recorded the event in her diary: "In the afternoon, to our great astonishment, we arrived off a large opening extending to the eastward, the entrance of which appeared to be about four leagues wide, and remained about that width as far as the eye could see, with a clear easterly horizon, which my husband immediately recognized as the long lost strait of Juan de Fuca, and to which he gave the name of the original discoverer, my husband placing it on his chart" (Howay 1911, 8).

The event is significant since Charles Barkley is generally credited with the positive discovery of the opening of the Strait of Juan de Fuca (Anderson 1960, 80). Barkley proceeded south, rounding the cape earlier named Cape Flattery by James Cook, and eventually anchored near the mouth of the Hoh River. Crew members from the Imperial Eagle were sent ashore and, like the Spanish explorers in 1795, met a similar fate. The Hoh River was named Destruction River by Barkley in commemoration of this occurrence (Wood 1968, 66).

A year later, in 1788, British Captain John Meares guided his ship, the Felice, through waters at the entrance of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. At present-day Neah Bay he encountered the Makah Indians and referred to the small island west of Cape Flattery as "Tatootche" after the chief. Although the reliability of Meares' personal account of his 1788 voyage is questioned by some historians (Howay 1911, 10-14; Morgan 1955, 18-22), Meares is credited with the renaming of El Cerra de la Santa Rosalia. As Meares sailed south past Destruction Island, he recorded viewing the citadel among the range of "lofty mountains. In the northern quarter it was of a great height, and covered with [s]now. This mountain, from its very con[s]picuous [s]ituation, and immen[s]e height, obtained the name of Mount Olympus" (Meares 1790, 163). Following close behind John Meares in the same year, British Captain Charles Duncan entered and surveyed the strait, executing what became the first published chart of the Strait of Juan de Fuca mapping such, then unnamed, Olympic Peninsula features as Cape Flattery, Neah Bay and Clallam Bay (Kohl 1860, 267-76; Howay 1911, 14-16).

For the next decade the Strait of Juan de Fuca, enveloping the Olympic Peninsula on the north, was thoroughly reconnoitered by several ship captains. Early in 1789, the Spanish, eager to establish sovereign possession of the Northwest coast, formed a settlement at Nootka in a protected harbor on the southern end of Vancouver Island. From Nootka several Spanish exploring expeditions were launched and contact made with points along the north Olympic Peninsula shore. An expedition led by either Don Gonzalo Lopez de Haro or Don Jose Maria Narvaez in 1789 explored the entrance to the strait (Kohl 1860, 274). Another Spaniard, Don Monval Quimper, explored the San Juan archipelago in 1790 and passed along the Peninsula coast as far east as New Dungeness and the area around present-day Port Discovery (Anderson 1960, 80; Kohl 1860, 279-80). Quimper is credited by some historians with the discovery of Neah Bay and Bahada Point, two miles to the east (Reagan 1909, 134). Francisco de Elisa (sometimes spelled Eliza) and Joseph Narvaez continued Quimper's exploration of the area in 1791 (Kohl 1860, 274). Both Quimper and Elisa are thought to have entered the protected harbor of Port Angeles. It was during these Spanish expeditions that this harbor was named Puerto de Nuestra Senora de los Angeles (Port of Our Lady of the Angels) (Morgan 1955, 22; Wood 1968, 67). A Spanish military post was established at Discovery Bay in 1791 by Francisco de Elisa (Wood 1968, 67), and the following year Lieutenant Salvador Fidalgo set up a Spanish colony with military fortifications at Neah Bay (Kohl 1860, 276). At this location Spain instructed its army to establish "a small battery on the mainland, respectable fortifications, provisional barracks for the sick, a bakery and oven, a blacksmith shop, and to cut down all trees within musket shot" (Morgan 1955, 22-23). The settlement was short-lived, lasting less than one year, but as late as 1909 bricks of the old fortification were still visible at the site (Reagan 1909, 124). Spanish admiralty charts published in 1795 attach Spanish place names to several points and bays along the north coast of the Olympic Peninsula.

While England and Spain reckoned for dominance in the area of the Strait of Juan de Fuca and Vancouver Island, a group of Boston merchants organized and sponsored a voyage of commerce and discovery to the Pacific Northwest. In the words of Charles Bulfinch, prime mover of this venture, "for the purpose of this voyage, the ship Columbia, under the command of John Kendrick, and the ship Washington, commanded by Robert Gray, were equipped, provided with suitable cargoes for traffic with the natives of the northwest coast . . ." (Jones 1947, 12). Gray and Kendrick departed Boston, Massachusetts, in the fall of 1787 and arrived almost a year later at Nootka. Enroute to Nootka in the spring of 1789, Captain Gray and the Washington apparently navigated further east along the north coast of the Peninsula to a point off Clallam Bay, twenty-five miles east of Cape Flattery. The claim that both Gray and Kendrick passed through the Strait of Juan de Fuca, however, is generally discredited (Howay 1911, 1732; Anderson 1960, 79). It was on Gray's second voyage from Boston, after he had succeeded to the command of the Columbia, that Gray discovered the harbor that now bears his name (Grays Harbor) and explored the mouth of the river which he named after his ship, the Columbia.

It was on Robert Gray's second voyage in the Columbia, in 1792, that he encountered British sea Captain George Vancouver near the mouth of the Quillayute River on the Olympic Peninsula. Before leaving England the year before, Vancouver was given specific instructions to investigate the little known Strait of Juan de Fuca. In April 1792, Vancouver entered the strait and for the next several weeks traced the shoreline of sections of the Olympic Peninsula, Hood Canal and Puget Sound before continuing north into the Gulf of Georgia separating Vancouver Island from the mainland (Anderson 1960, 76-80). Unaware that Spanish explorations in the Strait of Juan de Fuca had preceded him, Vancouver renamed several physical features on and near the Peninsula. These names have perpetuated to this day. New Dungeness Harbor, Port Discovery, Port Towns[h]end, Port Orchard, Hood's Canal, Puget Sound, Possession Sound, and Admiralty Inlet are a few of the waterways described and named by Vancouver. Mounts Rainier and Baker, highest and most conspicuous of the peaks rising from the Cascade Mountains in western Washington, were also sited and named by Vancouver (Anderson 1960, 80-86). Undoubtedly impressed with the grandeur of the cluster of peaks rising from the interior of the Peninsula, Vancouver's records indicate he adapted John Meares name, Mount Olympus, to the entire mountain range, calling it the Olympic Mountains. Eventually, the entire Peninsula was designated the Olympic Peninsula (Wood 1968, 67).

George Vancouver's description of the country he saw during his meanderings around the Olympic Peninsula in the spring of 1792 was prophetic:

To describe the beauties of this region, will on some future occasion, be a very grateful task to the pen of a skillful panegyrist. The serenity of the climate, the innumerable pleasing landscapes, and the abundant fertility that unassisted nature puts forth, require only to be enriched by the industry of man with villages, mansions, cottages, and other buildings, to render it the most lovely country that can be imagined; whilst the labour of the inhabitants would be amply rewarded, in the bounties which nature seems ready to bestow on cultivation (Anderson 1960, 86).

Early American Coastal Exploration

A century passed before Euro-Caucasian settlement of the Olympic Peninsula began in earnest. In the meantime, issues involving national possession of the Pacific Northwest were wrestled with by Spain, Russia, England and the United States while the U.S. accomplished slow westward expansion. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 extended United States lands from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains. Spain, in 1819, and Russia, in 1824-1825, surrendered their claims to the Oregon country which then extended from the Rockies to the Pacific Ocean. Great Britain and the United States remained the contenders of this large land mass until 1846 when President Polk signed a treaty with Great Britain, establishing the U.S. boundary line at the forty-ninth parallel, Washington's present northern boundary.

It was during the period when the United States engaged in the acquisition of new lands and establishment of its northern boundaries that several U.S. survey teams were dispatched to examine and survey the Northwest coast. Whether for the benefit of commerce, science or cartography, these various survey teams added substantially to the United States' knowledge of the terrain and natural features around the Olympic Peninsula. At the same time new place names emerged as these surveyors charted their discoveries on maps and described what they encountered in log books.

In 1838, the U.S. Congress sent a squadron of six vessels under the command of Lieutenant Charles Wilkes to circumnavigate the globe following a prescribed route. Specific instructions directed Wilkes to investigate the whale-fishing interests in the Pacific and to survey the Northwest coast (Bancroft 1884, 668). In August 1838, Wilkes set sail from Norfolk, Virginia, laden with supplies and a cadre of natural scientists and artists. Wilkes arrived in Olympic Peninsula waters in the spring of 1841. After entering the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Wilkes proceeded along the north Peninsula coast stopping at Port Discovery and Port Townsend before entering the Hood Canal and navigating through the waters of Puget Sound. Wilkes found the south shore of the Strait of Juan de Fuca "covered with a forest of various species of pines, that rises almost to the highest points of the range of mountains." He went on to describe the Olympic Mountains as "covered with snow; and among them Mount Olympus was conspicuous" (Wilkes 1845, 4:296). Wilkes estimated the elevation of Mount Olympus as 8,138 feet (Kohl 1860, 262). He is also credited with naming Mount Jupiter (or Jupiter Hills) outside the present Park boundaries in the east section of the Olympic range (Sainsbury 1972, 36).

Following Charles Wilkes came British naval sea Captain Henry Kellett (sometimes spelled Kellet) piloting the Herald. In 1846-1847 Kellett explored and surveyed many parts of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. During his surveying exploits, he assigned names to such north Olympic Peninsula coastal features as Clallam Bay, Crescent Bay, Striped Peak, Freshwater Bay and Sek[i]u (applying it to a point of land on the north shore of the Peninsula) and Ediz Hook at Port Angeles (Kohl 1860, 274; Hitchman 1959, 9).

George Davidson, who became internationally known for his work in geodesy and astronomy, led several survey parties on the Pacific coast between 1850 and 1895 for the United States Coast Survey. About 1856, while in command of the survey brig R. H. Fauntleroy, Davidson was determining the position and elevation of mountains on the Olympic Peninsula when he sited and named three prominent peaks clearly visible from Puget Sound: Mount Ellinor, Mount Constance, and The Brothers. In the Pacific Coast Pilot George Davidson describes these promontories: "Behind the Jupiter Hills is Mount Constance, 7777 feet elevation; The Brothers, 6920 feet, and Mount Ellinor estimated at 6500 feet. These great masses rising so abruptly in wild, rocky peaks are marks all over Admiralty Inlet and Puget Sound, but seem to overhang the main part of [Hood] Canal" (Meany 1913b, 182). After the naming of Mount Olympus, this was the first known naming of prominent mountain peaks in the interior of the Peninsula. Mount Constance, The Brothers and Mount Ellinor stand at the eastern edge of the present Park boundary. Although the coastline of the Olympic Peninsula was thoroughly surveyed and clearly delineated on maps by the mid 1850s, it was another quarter century before the unknown interior was penetrated by white exploration parties and settlers.

Interior Exploration

Early Reports. Exploration of the unknown and seemingly mysterious interior of the Olympic Peninsula occurred late in the history of Euro-Caucasian development of the Pacific Northwest. Delayed discovery and exploration of coastal waters around the Peninsula seemed to set a precedent for penetration of the Peninsula's interior depths. Distance from populated centers on the eastern seaboard, near total isolation from the Washington mainland by the waters of the Hood Canal, Admiralty Inlet and Puget Sound, dense forest, heavy precipitation and rugged terrain, were all effective deterrents to serious exploration of the Olympic Peninsula interior.

Lured by reports of the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804-1806, two major fur trading companies determinedly expanded their trapping and trade empire to the Pacific Ocean. When the Northwest Company and the Hudson's Bay Company merged in 1821 under the name of the Hudson's Bay Company, several trading posts were established throughout the Oregon Territory. In 1825 Fort Vancouver, on the north bank of the Columbia River, became the headquarters for the Pacific Northwest area of the British-chartered Hudson's Bay Company (Swan [1857] 1977, 377-380; Barto 1947, 35-46).

Perpetually searching for new areas of potential trapping and trading with the Indians, the Hudson's Bay Company encouraged explorations. During the first half of the 1800s, the officers of the Hudson's Bay Company are believed to have extensively explored the area around the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Agents and traders of the company often traveled between Fort Vancouver and Puget Sound (Kohl 1860, 265, 274). Little, if anything, of their explorations was ever published or survives to the present. The extent of the Hudson's Bay Company's travels on the Olympic Peninsula is, therefore, speculative.

Settlement of the coastal areas and lowlands on the Olympic Peninsula began in the mid 1800s (around the southern and eastern end of Puget Sound, the east side of the Hood Canal and various points around the north and west Peninsula coastline). The densely forested foothills and interior mountains, however, remained unexplored until much later. Although informal, unrecorded expeditions by roaming native Indians, trappers and miners are suspected to have taken place at an earlier date, the memory of these trips is lost. The first organized, well documented and publicized accounts of travels in the Olympic range did not take place until the late 1800s.

The earliest trip into the heart of the Olympic range was made in the summer of 1854. According to some records, the party consisted of Colonel Michael T. Simmons; F. Kennedy; Eustis Hugee, a surveyor; Henry D. Cock (or Cook); B. F. Shaw, woodsman; and four Cape Flattery Indians. Nothing of the party's route or details of the trip are known except that Shaw and Cock and two unidentified Indians reportedly made an ascent of Mount Olympus. George Himes briefly describes this "first ascent" more than fifty years after its occurrence and cites no source for his information. One is left to wonder about its authenticity (Himes 1907, 159).

Another undocumented trek across the Peninsula interior was accomplished in 1855. Passengers and crew from the shipwrecked Southern, landing at the mouth of the Quillayute River on the west coast, traveled by foot across the Peninsula to Port Townsend. Major John F. Sewell led a party from Port Townsend to the site of the wreck to retrieve the mail aboard. Although Sewell is credited with the first crossing of the Olympic range to the coast, records describing his route or the hike of the Southern's passengers have not been found (Hitchman 1959, 11).

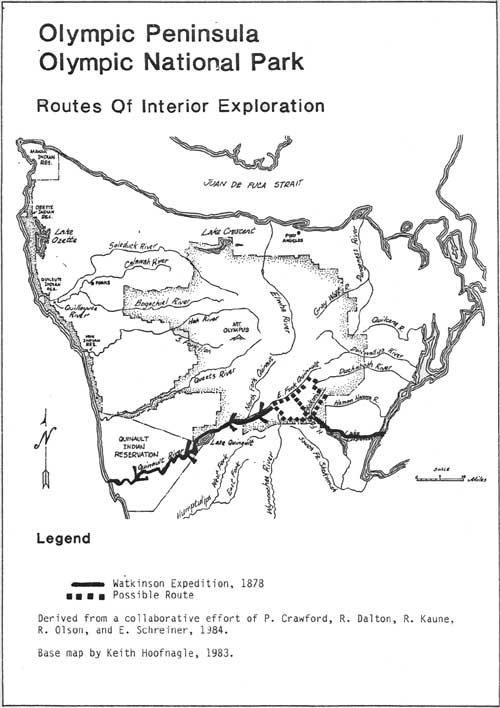

Watkinson Expedition. Around 1880 Eldridge Morse described an 1878 expedition into the southeastern section of the Olympics in his "Account of the only trip ever made by white men from Hood's Canal to the Ocean, over the top of the Olympic Mountains." (Univ. of California 1880) The party of five young men led by Melbourne Watkinson included, in addition to Watkinson, Charles and Benjamin Armstrong, George McLaughlin and Finley McRae, all hardy, strong woodsmen who had experience working in logging camps. According to Morse, Watkinson's troupe set-off from the west side of Hood Canal on the Lilliwaup Creek on 2 September 1878: they traveled west to Lake Cushman, proceeded up the North Fork Skokomish River, reconnoitered and possibly ascended Six Ridge, then headed for the Quinault River by way of either O'Neil Pass, or O'Neil or Graves Creeks. Finally, they proceeded down the Quinault River to its mouth on the Pacific Ocean. After walking south along the ocean beach to Grays Harbor, the adventuresome party made their way back to the Hood Canal. The entire trip took eighteen days and traversed a segment of the southern part of Olympic National Park (Univ. of California 1880; NFS OLYM 1977, 12 August). H. Fisher, traveling with the O'Neil expedition through the Olympics in 1890, notes in his diary that an O'Neil exploration party found the initials "M. W." and the names "Balentine, Brodie and McLaughlin" inscribed in two separate trees in the country traversed by the Melbourne Watkinson party. It is purely speculative as to whether the initials "M. W." stood for Melbourne Watkinson. The name "McLaughlin" may have referred to George McLaughlin who accompanied Watkinson on his autumn escapade. H. Fisher's diary entry was recorded on 21 July 1890 (NPS OLYM 1977, 12 August).

|

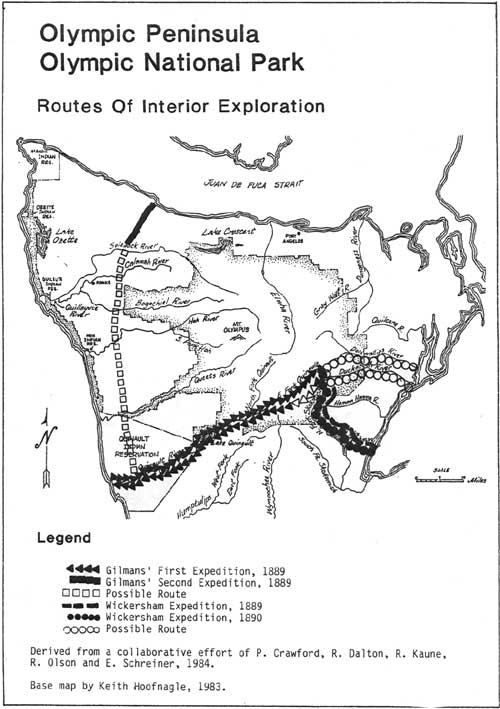

| Routes of Interior Exploration. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Smith Expeditions. From the early and mid 1880s there are two other existing reports of expeditions into the interior of the Olympic Peninsula near or just inside the present boundaries of Olympic National Park. An article entitled "That Unknown Land" in an 1890 issue of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported that "Mr. Smith has thoroughly explored the Olympic range of mountains." Norman Smith, whose roots went back to the founding of Port Angeles, is quoted as saying that he had "explored the country from time to time in innumerable directions." Among the explorations he cited were an 1881 trip from Quilcene Bay into the Jupiter Hills, just east of the Park boundary and, in the same year, a territorial road survey trek from Clallam Bay on the north Peninsula coast, across to Quillayute. Smith claimed that one year later he made a reconnaissance for a railroad planned between Port Townsend and Union City, both on the eastern edge of the Peninsula. In 1885 Smith reported that he accompanied Lieutenant Joseph P. O'Neil on the first of two explorations into the interior mountains of the Peninsula (Seattle PI 1890, 1 July). O'Neil's own report of his 1885 expedition includes Norman Smith as a member of the party (NPS OLYM 1885, 3). In 1885 a local north Peninsula resident, Billy Everett, was yet another early mountain adventurer who reportedly reached Cream Lake Basin in the heart of the Olympic Range (Olympic Mountain Rescue, The Mountaineers 1979, 5).

First O'Neil Expedition. In 1885 well-known explorer, U.S. Army Second Lieutenant Joseph P. O'Neil, executed his first of two expeditions into the Olympic Mountains. O'Neil's interest with the Olympics began in 1884 and 1885 when stationed at Port Townsend: "I was attracted by the grand noble front of the Jupiter Hills [just east of the present Park boundary], rising with their boldness and abruptness, presenting a seemingly impenetrable barrier to the farther advance of man and civilization" (NPS OLYM 1885, 1). To O'Neil it seemed clear that previous efforts to penetrate this "barrier" had been unsuccessful since inquiries about them elicited very little reliable information, and "it seemed to me that Jupiter Hills and the Olympic Mountains were almost as unknown to us as the wilds of Alaska" (NPS OLYM 1885, 1).

After O'Neil was restationed at Fort Vancouver earlier in 1885, General Miles of that fort selected the adventuresome young O'Neil to lead an exploration party into the unknown interior. His specific assignment was to "make a reconnaissance and find out, if practicable, what the country was, its character and its resources in case of military emergency" (NPS OLYM 1885, 3). With a party of seven; Sergeants Heargraff (or Neargraff), Green and Gore; Private Johnson; Engineers H. Hawgood and R. E. Habersham; and Port Angeles resident Norman Smith, O'Neil traveled overland from Port Townsend to Port Angeles in mid July 1885. Later in the trip an Indian guide and packer and a Mr. Pilcher joined the party (NPS OLYM 1885, 3, 11, 15).

The 1885 O'Neil party expedition traversed a sizable portion of rugged mountainous country now included in the eastern section of Olympic National Park. O'Neil's written record of the trip provides the first description of the route and events that took place during this exploration into the interior of the Peninsula. Leaving Port Angeles on 17 July 1885, the O'Neil party headed south-southeast and followed present-day Ennis Creek to its headwaters. O'Neil continued south and made a steep ascent into the area called The Sisters (now known as Mount Angeles and Klahhane Ridge). He was impressed by the scene before him: "Looking east, west and south, mountains, free from timber, some covered with snow, rise in wild, broken confusion. The grandest sight is a cluster of mountains about thirty miles or so due south of Freshwater Bay. This cluster I set down as Mount Olympus" (NPS OLYM 1885, 12). While camped in the area, O'Neil ascended "the lesser of the Sisters Peaks," probably present-day Klahhane Ridge (NPS OLYM 1885, 12).

The group then proceeded on to Hurricane Ridge at which point the party divided, one segment descending into the Elwha Valley and the other continuing along the ridge above Lillian River probably into what is known today as Cameron Basin. From the expedition camp there (referred to by O'Neil as "Noplace"), O'Neil and Private Johnson continued still further south to an area near Mount Anderson (NPS OLYM 1885, 13-14).

Without warning, Joseph O'Neil was unexpectedly halted from further reconnoitering of the interior mountain peaks and passes. By courier messenger, O'Neil was directed to report to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, for duty, and on 26 August he sailed from Port Angeles. Summarizing the expedition, O'Neil wrote: "The travel was difficult, but the adventures, the beauty of the scenery, the magnificent hunting and fishing, amply repaid all our hardships, and it was with regret that I left them before I had completed the work I had laid out for myself" (NPS OLYM 1885, 18). The O'Neil expedition of 1885 left behind one place name that has persisted to the present. The 6,800 foot peak of Mount Claywood was named for Assistant Adjunct General H. Clay Wood, who signed the orders for the 1885 O'Neil expedition (Olympic Mountain Rescue, The Mountaineers 1979, 6).

The enigma of the Olympic Mountains was not broken by Joseph O'Neil's 1885 trek in the jagged peaks of the eastern Olympic range. The mountains of the Peninsula continued to be publicized as "unknown," "wild," "untamed," and "mysterious." Perhaps one of the most colorful and hyperbolic descriptions of the Olympic wilderness was captured by the words of Eugene Semple, governor of Washington Territory. In 1888, impressed with the mountains' grandeur as he viewed them from the east side of Puget Sound, Semple sent a report of the Olympic Peninsula to the U.S. Secretary of the Interior. Both the prestigious West Shore magazine (1888) and the Seattle Press (1890) published Semple's report which in part, follows:

The space between Hood's Canal and the ocean is almost entirely occupied by the Olympic range and its foothills. The mountains seem to rise from the edge of the water, on both sides, in steep ascent to the line of perpetual snow as though nature has designed to shut up this spot for her safe retreat forever. Here she is [e]ntrenched behind frowning walls of basalt, in front of which is Hood's Canal, deep, silent, dark and eternal, constituting the moat. Down in its unfathomable water lurks the giant squid, and on its shores the cinnamon bear and the cougar wander in the solitude of the primeval forest. It is a land of mystery, awe inspiring in its mighty constituents and wonder-making in its unknown expanse of canyon and ridge (Semple 1888, 428-29; Seattle Press 1890c, 16 July).

Press Expedition. In 1889, when Elisha P. Ferry became the first governor of the State of Washington, he, like Semple, was enamored by the mysteries of the awesome, unexplored lands of the Peninsula. In response to Semple's and Ferry's expressed interest in the interior of the Peninsula, the Seattle Press newspaper published a story in the fall of 1889 challenging any "hardy citizens of the Sound to acquire fame by unveiling the mystery which wraps the land encircled by the snow capped Olympic range" (Seattle Press 1890a, 16 July) Numerous inquiries were made about the Press article. James H. Christie responded in a letter stating his qualifications for such an exploration, his desire to lead an exploring party and a request for financial support. The Press agreed to be the sponsor of an exploring group. By December 1889, a six-man team was organized, known as the "Press Exploring Expedition", with James Christie as leader (Seattle Press 1890a, 16 July).

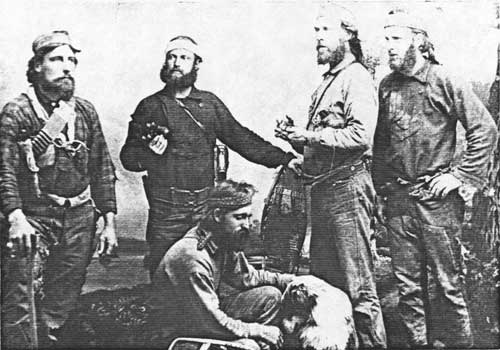

Members of the expedition included the following men: James Helbold (sometimes incorrectly spelled Helibol) Christie, the Press leader, was born in Scotland in 1854, served in a branch of the Canadian military forces, and later took part in a three year expedition to the Arctic; Captain Charles Adams Barnes, the party's topographer, was a native of Illinois born in 1859, and served in the military in the United States before later engaging in business in California; Dr. Harris Boyle Runnalls, M.D. (sometimes spelled Runnals), the party's natural historian, was born in England in 1854, and practiced medicine in several English hospitals before coming to America in 1888; John Henry Crumback, the expedition cook, was born in Ontario, Canada, in 1856 and was occupied at various times as a prospector, cowboy and hunter in the Northwest Territories before arriving in Seattle; John William Sims, born in England in 1861, served in the British army for six years and was later engaged in "hunting, trapping, prospecting and trading;" and Christopher O'Connell Hayes, born in 1867, who was occupied as a cowboy in the Yakima Valley in eastern Washington (Seattle Press 1890a, 16 July; Wood 1967, 19-22). The entourage was rounded out with four dogs and two mules. According to the Seattle Press, this group of hardy, young (half were thirty or under) individuals was reputed to "have [an] abundance of grit and manly vim," and unquestionably, "the people of the country had every reason to rest assured that these men would bring them a complete record of the unknown country within the Olympics" (Seattle Press 1890a, 16 July).

|

| Members of the Press expedition were photographed at the end of their trans Olympic Mountain trek, in Aberdeen, Washington on 21 May 1890. From left to right are Sims, Barnes, Crumback (kneeling), Christie and Hayes. (Courtesy of Mrs. Pierre Barnes and Mrs. Mary Buell) |

The expedition party was organized hastily in the late fall of 1889. Provisions provided by the Press amounted to 1500 pounds, and included "Winchester rifles, plenty of ammunition, a tent, canvas sheets, blankets, fishing tackle, axes, a whip saw for cutting out logs, a few carpenter tools, the necessary tools for mineral prospecting, rope, snowshoes [and] a small but well selected assortment of cooking and other utensils." Laden with supplies, the Press exploring expedition left Seattle by steamer headed for Port Angeles on 8 December 1889 (Seattle Press 1890a, 16 July).

As winter approached, the party of six gradually eased away from Port Angeles heading southwest toward the lower Elwha River where settlers in the area assisted in their preparations. Incessant rain, snow and cold weather, combined with persistent but unsuccessful attempts to construct and navigate a boat (Gertie) against the current up the Elwha River, delayed Christie and his men from making serious headway until mid February. (Dr. Runnalls left the party on 3 February.) After arriving in the vicinity of Griff Creek (tributary of the Elwha River) on 17 February 1890, the party slowly proceeded up the Elwha River, reaching Lillian Creek Creek by 1 April. By 1 May, the group was encamped in the upper drainage of the Goldie River below Mount Wilder. Descending down into the upper Elwha Valley once again, then making the steep ascent to Low Divide, the Press party started south down the North Fork Quinault River reaching the confluence of the North Fork Quinault River and Rustler Creek in mid May. By 19 May, Christie and his men, with the assistance of a local hunting party, arrived at Lake Quinault (at the southern Park boundary). One day later they floated by canoe to the mouth of the Quinault River on the Pacific Ocean. (A thorough, complete account of the Press exploring expedition is given in Robert Wood's Across the Olympic Mountains: The Press Expedition, 1889-1890.)

In slightly less than six months the Press expedition traversed the entire Olympic range from north to south, most of which is now in Olympic National Park. It was the first documented expedition to accomplish such a feat (Wood 1976, 201, 204-205). Numerous rivers, canyons, valleys, and mountain peaks and ranges were reconnoitered and named. No less than eighteen place names are currently in use, the most widely known including Mount Christie, Mount Barnes, Mount Ferry, Mount Seattle, Mount Meany (after Edmond S. Meany, writer for the Seattle Press), Mount Dana (after Charles Dana, editor of the New York Sun), Mount Noyes (after Crosby Noyes, writer for the Washington, D. C., Evening Star), Mount Scott (after James W. Scott of the Chicago Herald), and the Bailey Range (after William E. Bailey, publisher of the Seattle Press) (Wood 1976, 215-20). A hachure map, an early form of contour map produced by expedition member Charles A. Barnes, became the first published cartographic representation of Lake Crescent. As never before, this map delineated major peaks and valleys in the eastern portion of the Olympic Peninsula interior. In addition, some of the first high mountain winter scenes in the Northwest were photographed in the Olympic Mountains by Charles Barnes and are among the collections of the U.S. National Archives (Majors and McCollum 1981, 162). The approximate route of the Press expedition "trail" across the mountains (except where the party followed the Goldie River) was later incorporated into the Olympic National Park trail system.

Gilman Expeditions. While the Press expedition was making its arduous, prolonged trek across the Olympic Mountains, others stirred in the heavily forested peninsula interior. As it happened, 1889-1890 was an eventful two years for white explorers in challenging the Olympic wilderness and for acquiring new knowledge about its unexplored resources. Even as James Christie met with the Seattle Press publisher and staff in November 1889, another hiking expedition was in progress in the Quinault region of the Olympics. The last three months of 1889, former Lieutenant Governor of Minnesota, C. (Charles) A. Gillman, and his son, S. (Samuel) C. Gillman, followed the Quinault River from its mouth on the Pacific Ocean to its headwaters deep in the interior of the Olympic Mountains, covering much terrain now embraced by Olympic National Park.

On 17 October 1889 the Gilmans left the city of Grays Harbor by steamer. Despite heavy rainfall indicating the rapid approach of winter, the determined pair located a native at the Quinault Indian Reservation who agreed to take them thirty miles up the Quinault River by canoe. The trip began on 20 October. By 23 October, the party reached the north and east forks of the Quinault where the Indian, accompanied by his wife and their baby, made their departure. As the Gilmans proceeded up the east of the Quinault, they advanced into "the heart of the mountains," mountains that "were wildly rugged and broken" (Seattle PI 1890a, 5 June).

Unintimidated by the "frightening grandeur" of their surroundings, "they concluded to ascend some of the peaks and get a view of the surrounding country. After much travel, they got to the summit of several in succession" (Seattle PI 1890a, 5 June) but were unable to see the surrounding country because of thick fog. Finally, in early November they reached the summit of an unidentified peak "and there the view that burst upon their bewildered vision was glorious beyond description" (Seattle PI 1890a, 5 June). By mid November, C. A. Gilman and his son, back on the east fork of the Quinault, quickly repaired an old canoe they had spied earlier on the bank of the river and completed the last phase of their journey down the Quinault by canoe. They arrived back in Grays Harbor on 27 November (Seattle PI 1890a, 5 June. 1890, 5 June).

Soon after the Gilmans returned from their first expedition, they started on a second, this time penetrating the mountainous Olympic country from the north. In early December 1889, they set off from the mouth of the Pysht River on the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Finding no one there willing to accompany them on such a venture during the harsh winter months, the Gilmans proceeded up the Pysht River to the Beaver Post Office on the Soleduck River. There they succeeded in finding two men interested in making the journey southward and set off on 11 December. From the Soleduck River they traveled across the western margin of the Peninsula, again concluding their trip at the mouth of the Quinault River on 31 December 1889. They reached Grays Harbor on 4 January 1890 (Seattle PI, 1890a, 5 June). The Gilmans continued their expeditions across the Olympic Peninsula in 1890. Young S. C. Gilman made two trips into the interior in the spring of the year with a third planned. In mid 1890, senior Gilman expressed his intention to explore the headwaters of the Queets, Hoh and Quillayute Rivers (Gilman 1890, 725). As a result of their expectations, the Gilmans produced several written reports giving detailed accounts of the physical features and natural resources they observed. Their straightforward, matter-of-fact descriptions of elevations, river drainages, soil types, minerals and plant life were considered accurate and thorough and were published widely in major newspapers and periodicals in the Northwest (including the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Portland Oregonian and the West Shore magazine). In 1896 the National Geographic magazine published an article written by C. A. Gilman and the then late S. C. Gilman, in which they thoroughly described the Olympic country (Gilman and Gilman 1896, 133-39). Impressed with the Gilmans' accounts, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, in 1890, exclaimed that "no work of equal importance and value in a practical sense has been accomplished on the American continent in the past quarter of a century. It opens up the last remaining bit of unknown country within the United States (excepting Alaska)" (Seattle PI 1890a, 5 June). The myths and mysteries of the interior of the Olympic wilderness were being unraveled.

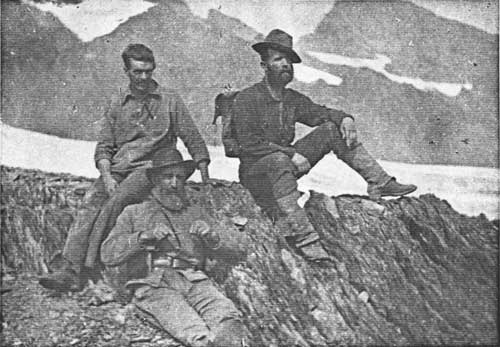

Second O'Neil Expedition. In addition to the Press and the Gilman's explorations, 1890 was the year of Lieutenant Joseph O'Neil's second expedition into the interior of the Olympics. During that summer, the expedition was organized "for the purpose of passing through the Olympics from east to west climbing Mt. Olympus en route, and making abundant side trips" (Henderson 1932). The expedition was sponsored by the U.S. Army under the auspices of General John Gibbon and the Oregon Alpine Club (forerunner of the Portland Mazamas hiking club) founded by William Gladstone Steel (Olympic Mountain Rescue, The Mountaineers 1979, 7). With Steel's assistance, Joseph O'Neil assembled his expedition party. The entourage consisted of ten enlisted men, five civilians, including three scientists recruited by the Oregon Alpine Club, plus Indian packers, a dozen pack animals and one dog named Jumbo. Members of the team were: Yates and Marsh; Corporal Haffner; Privates Danton, Bairens, Fisher (James Hanmore), Higgins, Hughes, Kranichfeld, Krause; and civilians Frederic Church and M. Price. Three scientists representing the Oregon Alpine Club—Bernard J. Bretherton, naturalist; Louis F. Henderson, botanist; and Nelson E. Linsley, noted mining engineer, mineralogist and geologist—completed the team (NPS, OLYM 1890, 2; U.S. Congress 1896, 2-3; Wood 1976, 54). Remarking on the scientific contingency, expedition member Private Fisher humorously commented in his diary: "It is suffice [sic] to say that the scientific branch of our party were men of means and prominence and it was no small sacrifice for them . . . [to deny] many luxuries, such as feather beds, pies, cakes, & tarts, which the Olympics did not produce" (Wood 1976, 54).

Unlike his 1885 expedition beginning at the north end of the Peninsula, Lieutenant O'Neil planned to enter the mountains from the east and proceed westward to the Pacific Ocean. On 26 June the party's ten enlisted men and enough supplies for a "three month's siege" assembled in Port Townsend (Wood 1976, 55). Soon after, the collection of men, animals and supplies navigated by sternwheeler down the Hood Canal to the mouth of the Lilliwaup Creek. With the civilians joining the military troupe at various points along the way, the entourage finally set off over a rough trail to Lake Cushman in early July (U.S. Congress 1896, 3-6).

|

| At the outset of their 1890 trip, O'Neil expedition members and packhorses were photographed "awaiting laggards at the North Fork Skokomish River." (Courtesy of National Archives and Record Center, RG 393, Olympic Mountains Exploring Expedition, 1890) |

|

| Members of the O'Neil expedition gathered around an Oregon Alpine Club (OAC) flag at "Camp Nellie Bly" during their 1890 Olympic exploring expedition. (Courtesy of National Archives and Record Center, RG 393, Olympic Mountains Exploring Expedition, 1890) |

Slowly they proceeded up the Skokomish, cutting a trail passable by the pack animals as they went. O'Neil soon established a pattern of sending out exploring parties, leaving a sizable number of trail workers to continue work on the main trail (U.S. Congress 1896, 3-6). The first of these exploring parties headed up into jagged cliffs and snowfields ascending a peak (probably Mount Lincoln, just inside the Park boundaries) about ten miles west of Lake Cushman. As the sun was setting, they reached the summit and were overwhelmed by the ruggedness and grandeur of the country that stretched before them, much of which is now embraced by Olympic National Park boundaries. Inspired by the view, botanist Louis Henderson described the spectacle:

A more magnificent scene had never presented itself to my eyes, and I doubt whether anything in the higher Alps or the grand ice-mountains of Alaska could outrival that view . . . . Canyon mingled with canyon, peak rose above peak, ridge succeeded ridge, until they culminated in old Olympus far to the northwest; snow, west, north and south; the fast descending sun bringing out the gorgeous colors of pale-blue, lavender, purple, ash, pink and gold. Add to this the delightful warmth of a summer sun in these altitudes—the awful stillness broken every now and then by the no less awful thunder of some distant avalanche—a fearful precipice just before us down which a single step in advance would hurl us hundreds of feet#151;and one can form some slight idea of the reasons that compelled us to gaze and be silent (Wood 1976, 104-105)."

The expedition party and parade of pack mules went on up the North Fork Skokomish. Circling around the north side of Mount Steel to O'Neil Pass, they descended into Enchanted Valley and followed the Quinault River to Lake Quinault. Throughout the three month trip, O'Neil dispatched several side parties that explored and mapped the drainages of the Dosewallips, Duckabush, North Fork Skokomish, Humptulips, Wynoochee, Satsop, Wiskah, North and East Forks of the Quinault, and the Queets Rivers (Olympic Mountain Rescue, The Mountaineers 1979, 7; U.S. Congress 1896; Wood 1976, maps). An account of the sometimes perilous adventures and actual trip routes taken by O'Neil's main expedition scout parties is thoroughly described in Robert Wood's Men, Mules and Mountains.

It was one of the O'Neil expedition's side parties that made what is generally conceded to be the first ascent of Mount Olympus. In mid September a party of six men, led by Nelson Linsley, set out from O'Neil Pass heading northwesterly to the Queets Basin. Ascending to the head of Jeffers Glacier on the south flank of Mount Olympus, Linsley, Bretherton and Private Danton reached the summit of one of the three Mount Olympus peaks on 22 September 1890. In rocks near the summit, the trio planted a copper box belonging to the Oregon Alpine Club. It contained a book for future climbers to record their names and descriptions of their trips along with various trinkets. To this day the box has never been found (Bretherton 1907, 148-53; Olympic Mountain Rescue, The Mountaineers 1979, 7).

In early October a main contingent of the O'Neil expedition arrived in the town of Hoquiam, thus completing the first crossing of the Olympic Mountains from east to west. As a result of the prodigious amount of work accomplished by O'Neil and his men in their 1890 expedition, the body of knowledge about the interior of the Peninsula expanded. Samples of rock and plant specimens were collected and examined. A map tracing the routes of the expedition parties was published in 1891 (by William Steel). Photographs, records and reports of O'Neil and several expedition members documented the daily events and routes of travel, geology, hydrology, wildlife and plant life encountered throughout much of the southern half of the Olympic range. Dramatized accounts of the O'Neil expedition were widely reported in major cities in western Washington and Oregon. O'Neil and others in his group made appearances before audiences eager to learn of this terra incognita that had been wrapped in mystery for so long.

|

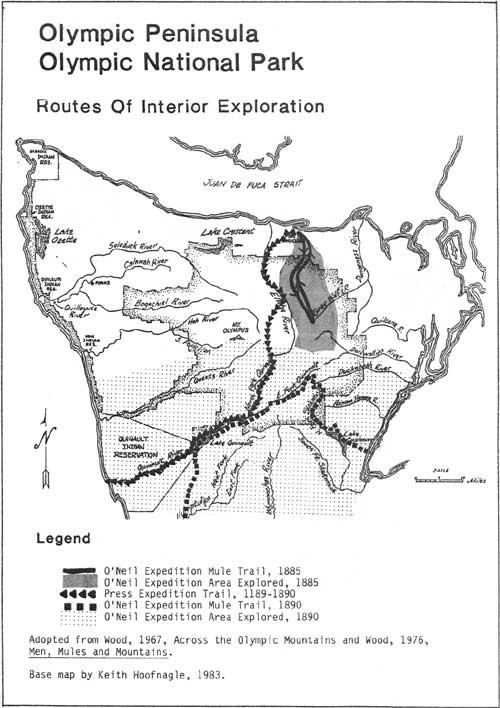

| Three members of the 1890 O'Neil expedition posed "near the summit of Olympus." (Courtesy of National Archives and Record Center, RG 393, Olympic Mountains Exploring Expedition, 1890) |

Today, reminders of the O'Neil exploring expedition exist in the form of extant sections of O'Neil's trails and in place names of prominent physical features. Sections of trail blazed by the O'Neil expedition members are now part of the currently maintained trail system in Olympic National Park. Contemporary place names in or near the present Olympic National Park boundaries that commemorate the 1890 O'Neil expedition include Mounts Anderson (for Colonel Thomas M. Anderson, O'Neil's commanding officer), Bretherton, Church, Henderson, O'Neil (after members of the 1890 expedition party), and Steel (after William G. Steel), O'Neil Pass, O'Neil Peak and O'Neil Creek (Hitchman 1959, 16-17).

The legacy of the O'Neil expedition that, perhaps, has persisted the longest was contained in O'Neil's summation of the potential resources of the Olympic Mountains written to the 54th U.S. Congress: "In closing," O'Neil wrote in 1896, "I would state that while the country on the outer slope of these mountains is valuable, the interior is useless for all practical purposes. It would, however, serve admirably for a national park. There are numerous elk—that noble animal so fast disappearing from this country—that should be protected" (U.S. Congress 1896, 20).

|

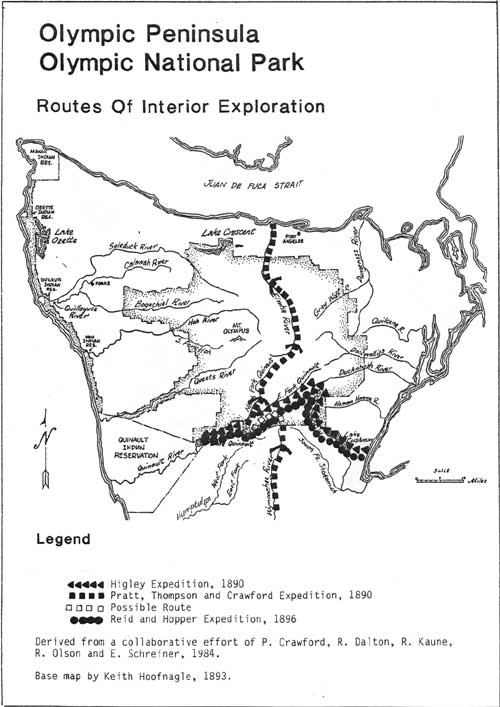

| Routes of Interior Exploration. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Wickersham Expeditions. In 1890 yet another man was both venturing into the unknown wilderness of the Olympic Mountains and sharing O'Neil's view that the Olympic Mountains deserved national park status. Impressed by the rugged grandeur of the Olympic Mountains, James Wickersham wrote in 1891: "The beauty of Switzerland's glaciers is celebrated yet the Olympics contain dozens of them, easy of approach and exhibiting all the phenomena of glacial action. A national park should be established on the public domain at the headwaters of the rivers, centering in these mountains. . . . The reservation of this area as a national park will thus serve the twofold purpose of a great pleasure ground for the nation and be a means of securing and protecting the finest forests in America" (Wickersham 1961, 6, 9).

Judge James Wickersham, widely known and respected for his involvement in Washington state and later Alaskan politics, was an avid outdoorsman. His appreciation for the Olympics, in fact, was based on personal observation of the eastern section of the mountains acquired during summer hikes in both 1889 and 1890. While only scanty documentation exists of Wickersham's 1889 Olympic outing, a letter from Wickersham's son, D. P. Wickersham, written to Robert Hitchman in 1947, mentioned that Judge Wickersham "went deep into the Olympic Mountains in 1889" (Washington State Historical Society 1947, 9 November). Joseph O'Neil, reporting to the U.S. Congress on his own 1890 Olympic expedition, also mentions Wickersham's 1889 summer outing (U.S. Congress 1896, 7). An 1890 article appearing in the Seattle Press recounts that Judge Wickersham, accompanied by Charles W. Joynt, "traveled about twenty miles up the Skokomish, when they ran short of grub and time and had to retrace their steps" (Seattle Press 1890b, 16 July).

In 1890, under the sponsorship of the Buckley Banner newspaper, Wickersham left Tacoma, Washington, with a party of four men and six women, including several family members. While some of the party stayed behind at Lake Cushman, three men and three women proceeded up the Skokomish River. About eight miles above Lake Cushman, the Banner party encountered members of the O'Neil expedition at the O'Neil camp on Five Stream. Private Fisher, returning to camp from trail building, remarked that the camp "now had more the appearance of a parlor scene than an African jungle" (NPS OLYM 1890, 25).

The Banner party continued up the North Fork Skokomish River to its headwaters, intending then to follow the Elwha River north to Port Angeles. Inadvertently, the group turned eastward, descending to the Hood Canal via the Dosewallips River. After completing 125 miles on foot, the Wickersham party emerged from the woods and returned to Tacoma on 10 August (Washington State Historical Society 1947, 9 November; Wickersham 1961, 5). The Banner party was allegedly the first to explore some of the high river source region in the Olympic range and to descend the Dosewallips River. Shortly after the trip, James Wickersham produced the first known map delineating the boundaries of a national park. It accompanied a report proposing the establishment of an "Olympic National Park" (Wickersham 1961, 5, 12).

|

| Routes of Interior Exploration. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Higley Expedition. Alfred V. Higley had no thoughts of a national park in the mountainous interior of the Olympic Peninsula when he and his son, Orte, traversed the southern portion of the Olympic range in 1890. Higley, instead, was intent on establishing a home at the newly formed settlement on Quinault Lake. Born in 1849 in East Hebron County, Pennsylvania, Alfred Higley was only a teenager when he enlisted in the Union army. Later on in the Civil War he was with General William Sherman on his renowned March to the Sea. After marrying, Higley and his family settled in Kansas. Following the death of his wife and daughter in 1888, Alfred Higley and his then nineteen year old son, Orte, traveled west, and after a brief stay in Pueblo, Colorado, they headed to the Pacific Northwest. The father and son team arrived in Seattle on Christmas day 1889. It was while in Seattle that they learned of the new settlement on Quinault Lake (Aberdeen Daily World 1966, 26 January; 3, 11, 19, 25 February; 5 March).

In August 1890, fully outfitted for their journey, the Higleys sailed by sternwheeler from Seattle down the Hood Canal. At Hoodsport they disembarked and entered the mountains only a few weeks after Joseph O'Neil's second exploring expedition set off into the Olympics. Alfred and Orte Higley, accompanied by Fritz—Herbert Leather, Peter Hartney and Le Barr, started their trek up the North Fork Skokomish River. According to an account written by Orte Higley many years later, the party camped at Duckabush Divide for four days before proceeding to the head of the Duckabush River and the Quinault Divide (Higley 1973, 181). At Hart Lake, near present-day O'Neil Pass, the Higley party encountered the O'Neil party. A few days later the Higleys moved their camp to Little O'Neil Creek and stayed there for three weeks. By early October 1890, the Higleys traveled down the East Fork of the upper Quinault River and arrived at Quinault Lake where they selected a homesite and later became prominent members of the settlement there (Aberdeen Daily World 1966, 26 January; 3, 11, 19, 25 February; 5 March; Higley 1973, 181).

Prospectors, Scientists and Recreation Hikers. Although the Press and O'Neil exploring expeditions of 1889-1890 were widely publicized in newspapers of the day and are today probably the best known of all the early Olympic expeditions, these two parties were not alone in the mountains. In the last decade of the nineteenth century, parties penetrated nearly every major river drainage surrounding Mount Olympus. Fascination with the unknown expanse and wild beauty was only one source of motivation for these pioneering explorers. A keen desire to know and to tap the wealth of the region's resources was another.

Several prospecting parties entered the mountains in 1890. Following the return of the Press party, five prospectors set off in June from the mouth of the Dosewallips River on the Hood Canal and traveled over the mountains to Port Angeles via the Elwha River. Reporting the trip to the Seattle Press newspaper, expedition member John Conrad wrote of the small fertile valleys limited patches of good timber and abundance of bear, cougar, elk, deer, woodchuck and grouse encountered on the trip. The group apparently found no evidence of minerals (Hanna 1907, 29).

Contrary to Conrad's report, other prospecting expeditions of 1890 found the Olympics a great potential storehouse of minerals. Norman R. Kelley, resident of Seattle and sponsor of several exploring expeditions into the Olympic mountains (Seattle PI 1891, 1 January), received reports of gold, silver, cinnabar, tin, coal, iron and copper from his expedition leaders. Several fine agricultural valleys were also discovered, notably in the Satsop River Valley, and immense timber was located in the section around the Wynoochee River (near the southern boundary of Olympic National Park) (Seattle PI 1890, 26 June).

One of Kelley's prospecting parties, consisting of George Pratt, Theodore H. Thompson and Ira Crawford, traveled through the Olympic Mountains from south to north. Starting in late June 1890 from Shelton on the Hood Canal, the party moved westward into the Wynoochee River drainage. About a mile upriver from a 100 foot high waterfall, they found evidence of previous visitors in the area. The bark of a tree was inscribed with the name "Lewark 1971" and "Lew Shelton" and "Turpin", "1875" (Seattle PI 1890, 14 August). The trio continued up the upper Wynoochee on an Indian trail ascended a peak at the headwaters of the river and then dropped down into the East Fork Quinault River drainage. Proceeding westward they climbed over the ridge to the North Fork Quinault and traveled upstream where they encountered a Press expedition camp. Pratt, Thompson and Crawford found several more Press party camps as they traversed rugged country on their northward trek. In early August, Pratt and Thompson ascended what is probably now Mount Christie and named it Kelley's Peak in honor of Norman R. Kelley who had outfitted them for the trip. Passing through Low Divide, the Pratt party then descended down into the upper Elwha River Valley and, after passing several more Press expedition camps, arrived in Port Angeles on 8 August. Although unsuccessful in finding great quantities of gold, the party leader George Pratt reported that, "This region abounds in almost every mineral except gold" (Seattle PI 1890, 14 August).

Equally promising reports of mineral wealth in the Olympics came from DeFord, Buckley and Seamon who conducted a prospecting expedition up the Quinault River in the late spring of 1890. Mr. DeFord had apparently "cruised in this unknown part of the world more than any other man" (Mason County Journal 1890, 2 May). In August James McCauley, an Alaskan prospector, and Clarence M. Wallace, a businessman from Minneapolis, went on a three week prospecting tour in a section of mountains west of Hood Canal (Mason County Journal 1890, 22 August).

Prospectors as well as hunting parties continued to penetrate the Olympics throughout the 1890s. In 1894 a party consisting of A. M. Godfrey, D. W. Starrett and W. Daggett reached the pass between the Elwha and Queets drainages. H. B. Herrick also traveled through this area in 1900. A record of these two parties' travels was contained in a tin and found in 1907 by Mountaineers (Banks 1907, 86).

A small party of hunters living near Lake Cushman, of which Frank Reid and Roland Hopper were members, entered the mountains in July 1896 with provisions to last six weeks. Following the 1890 route of the O'Neil expedition, they proceeded up the Skokomish River, continued on to the headwaters of the Duckabush River and descended into the Quinault River Valley. Frederic J. Church, member of the 1890 O'Neil expedition, guided the party through the mountains (Seattle PI 1896, 8 October). One year later Fred Church again ventured into the Olympics on a prospecting and exploring trip, this time accompanied by R. H. Young. In search of mineral-bearing ledges, the pair traveled up the Skokomish and more or less followed in O'Neil's path as far as O'Neil Pass.

|

| Routes of Interior Exploration. (click on image for a PDF version) |

After conducting searches in several directions they retraced their path down the Skokomish River (ST 1897, 17 July). Two years later a hunting party consisting of three lawyers and a physician ascended the Elwha Valley to the Low Divide area. Martin Humes, resident of the lower Elwha River, served as the expedition party's guide (Johnson 1902, 191-93).

Only scanty records remain of these early prospecting, hunting and exploring expeditions into the Olympic interior. Undoubtedly, there was much more travel through the interior of the Peninsula than ever gained recognition by newspapers in the 1890s. Only three years after Eugene Semple wrote his fanciful description of the Olympic interior, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer confidently reported the new status of the "wild Olympic range":

The sum of knowledge as to their character is about complete. The effect is to divest them of that glamour of romance which has hung over them for years and to expose them in their true light—of a country very mountainous with streams abounding in fish, with vales of great fertility, with timber resources of immense value, and with game of larger varieties in almost untold numbers. The mineral wealth of the country is as yet an uncertain quantity (Seattle PI 1891, 1 January).

Dodwell-Rixon Survey. The surveying team of Arthur Dodwell and Theodore F. Rixon ushered in an era of distinctly scientific exploration in the interior of the Olympic Peninsula. Under the direction of geographer Henry Gannett of the U.S. Geological Survey, Dodwell and Rixon surveyed 3,483 square miles of the newly created Olympic Forest Reserve between 1897 and 1900. Systematically, Dodwell and Rixon, with their assistants, gathered information on "the timbered, burned, cut and nontimbered areas; the depth of humus and forest litter; the total stand of timber and the principle species recognized by the lumber trade; the average height, diameter and clear length; and the percentage of dead and diseased trees." Ninety-seven townships, or partial townships, were surveyed in all (U.S. Department of the Interior 1902, 12; Olympic Mountain Rescue, The Mountaineers 1979, 8).

Based on field notes taken by the Dodwell-Rixon team, only sixteen square miles had been logged; nearly sixty-one billion board feet of timber was embraced by the Olympic Forest Reserve with the densest stands in the northwest and southern tier of townships. Small mining operations (principally gold and copper) were reported in the Elwha River drainage. Experiments in farming appeared unprofitable due to the great expense in clearing timber from the level portions of land. Through the meticulous and thorough work of Dodwell and Rixon, a topographic map of the entire reserve was prepared showing the principal streams and mountain peaks (U.S. Department of the Interior 1902, 13-16; Scientific American Supplement 1902, 21882). Although the record of mountain ascents of the Dodwell-Rixon team is lost, it is realistically possible that team members climbed all of the technically unchallenging peaks that were in or near timbered areas of the reserve. It is suspected that they climbed Mounts Carrie, Queets and Noyes (Olympic Mountain Rescue, The Mountaineers 1979, 8).

Early Mountaineering and Scientific Expeditions. Jack McGlone (sometimes spelled McGloon) a packer for the survey party, did make the first verified ascent of the East Peak of Mount Olympus. Leaving the Dodwell-Rixon team, encamped near the divide between the Hoh and Humes Glaciers on the eastern flank of the mountain, McGlone set off for the summit on 12 August 1899. Upon reaching East Peak, McGlone recorded his ascent by leaving behind a clipping from a Shelton, Washington, newspaper. (Roloff 1934, 222; Olympic Mountain Rescue, The Mountaineers 1979, 8).

In 1900 a Professor Elliot, head of the Field Columbian Museum in Chicago, led a scientific expedition into the north side of the present Park. Elliott and his two assistants spent several weeks in the vicinity of the Elwha River drainage collecting and classifying hundreds of specimens of flora and fauna found in the region. According to Elliott, a number of plants and animals found were "new to science." With experience investigating "all the known and accessible mountain ranges of the world," Professor Elliot reported, "that the Olympics were a thing apart from them all." "Nowhere," he declared, "did any of the mountain ranges of the world excel in ruggedness and scenic grandeur the heart of these mountains" (Smith 1907, 144).

Scholars representing Harvard University came to the Olympic Peninsula in 1907 in search of "flora and fauna to complete their records of the Olympics" (Olympic Leader 1907, 2 August). A party consisting of Roland B. Dixon, H. J. Spinder (from Cambridge, Massachusetts), George F. Wells (from Bismarck, North Dakota), and Richard Hillman (from Cincinnati, Ohio) spent approximately five weeks in the area around Mount Constance, Mount Olympus and the headwaters of the Duckabush River. Descending into the Quinault River Valley, they met guides and canoes who transported them to Hoquiam, Washington (Olympic Leader 1907, 2 August).

Men of science were also interested in the Olympic Mountains for the challenging mountaineering experience they offered. Virgin peaks, unconquered and some still unnamed, attracted skilled mountaineers, some from great distances, in the early 1900s. The conquest of Mount Olympus was the primary objective for a party of four that left Port Angeles on 9 July 1907. Professor Herschal (sometimes spelled Hershel or Hershell); C. Parker, head of the physics department at Columbia University; Walter G. Clark (sometimes spelled Clarke), of the then prominent New York electrical supply firm of Kilbourne, Clark and Company; Belmore H. Browne, of burgeoning fame as an artist and a resident of Tacoma, Washington, and Port Angeles resident Dewitt C. Sisson made up the team. Will Humes, homesteader in the Elwha Valley, joined the expedition (Grant Humes, brother of Will, made an unsuccessful attempt on Mount Olympus in 1905 (Humes 1907, 11-12).) Parker, Clark and Browne were among the foremost American mountaineers of the day and belonged to the National Geographic Society of Washington, D.C. Herschal Parker was one of the founders of the newly formed American Alpine Club, and both Parker and Browne were members of the prominent Explorers Club of New York City. In 1906 Parker and Browne accompanied Frederick A. Cook in his attempted ascent of Alaska's Mount McKinley and were well prepared for the attempt on Mount Olympus (Olympic Mountain Rescue, The Mountaineers 1979, 8-9; Port Angeles Tribune-Times 1907, 2 August).

Heading up the Elwha River to its source, the expedition team crossed Dodwell-Rixon Pass, which they named for the 1898-1900 survey team, and set up their base camp at the foot of a glacier on the east-facing flank of Mount Olympus. They named it Humes Glacier. After assessing the best route of ascent, the party of five edged their way up Humes Glacier. On 17 July they gained the summit of the Middle Peak of Mount Olympus. A record of their ascent was left in a tin can at the summit (Browne 1908, 195-200). In summarizing his impressions, Belmore Browne gave a romantic description of the Olympic Peninsula interior in 1908:

The celebrated coast range of Alaska is not more difficult to penetrate than these forest darkened crags. It is a land of dense forest and down timber, where the explorer at times cannot chop his own trail through the matted underbrush; of knife-like ridges and deep can[y]ons, where the roar of glacier rivers disturbs the silence, as they twist and plunge in their course to the sea (Browne 1908, 195).

Exploration and first ascents of Olympic peaks were becoming a coveted experience for the adventurous by 1907. The fledgling Mountaineers hiking club from Seattle was heartily disappointed when they learned they would not be the first to ascend the Middle Peak of Mount Olympus. The Parker, Browne and Clark party preceded the Mountaineers by less than a month. Although the purpose of The Mountaineers' expedition was to make as many ascents as possible in a short time, Mount Olympus, highest peak in the range, was the principal objective.

In preparation for The Mountaineers' outing, noted Northwest photographer Asahel Curtis, accompanied by W. M. Price and Grant Humes, reconnoitered the area around Mount Olympus in late May 1907, reaching an elevation of 7,000 feet on the flank of the mountain (Smith 1907, 145; ST 1907, 16 June). During the pre-trip reconnaissance, the summits of Mount Noyes and Mount Queets were reached (Banks 1907, 81, 85). After long months of planning, a total of sixty-five climbers, twenty-six of whom were women, joined The Mountaineers for their first annual outing. Certain members were assigned duties as recorders of scientific data and of events encountered on the trip, including Henry Landes (geologist), Theodore Frye (botanist), Asahel Curtis (photographer), and Mary Banks (historian). Several members of the Smithsonian Institute were also among the entourage (ST 1907, 24 July; The Mountaineers library 1907a, n.d.).

The group left Port Angeles in two contingents—the first in late July followed by the second in early August. After traveling up the Elwha River, a base camp was established in the Elwha Basin. With great military regularity, "companies" of varying sizes were organized at the base camp and ascended several peaks in the area in late July and early August including Mounts Noyes, Christie, Meany, Queets, Seattle and Barnes (Tacoma Daily News 1907, 17 August).

Mount Olympus remained the prize. Driven back by snow and heavy winds, the first attempt on the summit on 10 August was unsuccessful. The weather soon cleared and between 12 and 15 August all three Mount Olympus peaks were scaled. Although The Mountaineers found records of previous climbers on East Peak (Jack McGlone, 1899) and Middle Peak (Parker, Browne and Clark party, 17 July 1907) the highest, West Peak, appeared virgin. On 13 August the party of eleven left their own record at the summit (Nelson 1907, 34-37). Two women were among the climbing parties that reached the summit of each of the three peaks. Anna Hubert, who climbed West Peak and Middle Peak and Cora Smith Eaton, who ascended East Peak and Middle Peak, are believed to be the first women ever to reach the summits of Mount Olympus (The Mountaineers library 1907b, n.d.; Banks 1907, 83, 84).

The Mountaineers 1907 venture into the heart of the Olympic Mountains marked the first penetration of the interior Peninsula by a large group. Their 1907 hiking expedition was, perhaps, a milestone in the history of exploration of the Olympic Peninsula. Unlike any group before them, they took a large force of hikers, including women, into the mountains, successfully reached the summits of several peaks and climbed all three peaks of the lofty and extolled Mount Olympus. Their accomplishments and details of the country they traveled through were widely reported in newspapers throughout the Northwest. Such a feat must have seemed remarkable to the general public, who previously may have known only of hardy "mountain men" and intent scientists and miners venturing into the impenetrable forests and jagged mountain slopes. Although there was much of the Peninsula that was still unexplored and uncharted, The Mountaineers expedition marked the dawn of an era where, increasingly, the Olympic interior was seen less as mysterious and foreboding and more as a country that might enhance one's personal wealth and pleasure.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

While the Olympic Peninsula has been an area well-known to its habitants for at least 6,000 years (see Bergland, Summary Prehistory and Ethnography, Olympic National Park, Washington), three centuries of European exploration and the eventual domination of the area by Europeans and Anglo-Americans left a permanent legacy of place-names throughout the region. As Spanish, Russian, English and American captains navigated the area, they named places from the Strait of Juan de Fuca to the Columbia River. Understanding the origin of these many names provides a capsulated history of this great era of European exploration, the quest for the inland passage, the contest for sea otter and other valuable furs, and the eventual hegemony of English and American interests.

Following this long period of oceanic exploration, the short half-century between 1850 and 1900 witnessed the first penetration of the interior and its thorough description by teams of adventurers and scientists, groups of hikers from nearby cities, and those hoping for wealth in the unknown mineral zones of the Olympics. While earlier explorers in other parts of the United States often went months and years without popular notice, the developing communication media of the late nineteenth century brought the experiences of these exploring expeditions to immediate popular notice. O'Neil's first and second trips, the Press Expedition, the Gilman trek and other efforts by prospectors, scientists, hiking groups and others all removed the veil of mystery that once shrouded the interior.

Several of these trails, particularly the O'Neil, Press and Gilman, are now portions of the trail system in Olympic National Park and can be so identified. Careful research regarding specific sections of original routes, some marked today by still extant trail blazes and other marks, could result in National Historic Trail or National Register designation and, more significantly, increased appreciation of the many years of backcountry use within the Park. As an interpretive forum for both front and backcountry visitors, these early expeditions offer the first recorded perceptions of the awesome grandeur of the Olympics, a perception that remains remarkably unchanged nearly a century later.

REFERENCES CITED

| 1966 | Aberdeen Daily World (Aberdeen, Washington). 27 January; 8, 11, 19, 25 February; 5 March. The Higleys, Lake Quinault pioneers. Rowena Alcorn and Gordon Alcorn. |

| 1960 | Anderson, Bern. The life and voyages of Captain George Vancouver. Seattle: University of Washington Press. |

| 1884 | Bancroft, Hubert Howe. The works of Hubert Howe Bancroft. Vol. 27, History of the Pacific Northwest coast. San Francisco: A. L. Bancroft and Company, Publisher. |

| 1907 | Banks, Mary. Mountaineers in the Olympics. The Mountaineer, September, 75-86. |

| 1947 | Barto, Harold E. and Catherine Bullard. History of the State of Washington. New York: D. C. Heath and Company. |

| 1983 | Bergland, Eric O. Summary prehistory and ethnography of Olympic National Park, Washington. Seattle: Pacific Northwest Region, National Park Service. Seattle: N.p. |

| 1907 | Bretherton, B. J. Ascent of Mount Olympus. Steel Points, July, 148-53. |

| 1908 | Browne, Belmore. The first ascent of Mount Olympus. Recreation, November, 195-200. |

| 1890 | Gilman, S. C. The Olympic region. West Shore, 7 July, 724-25. |

| 1896 | Gilman, S. G. and C. A. Gilman. The Olympic country. National Geographic, 4 April, 133-39. |

| 1907 | Hanna, Ina M. Expeditions into the Olympic Mountains. The Mountaineer, June, 29-32. |

| 1932 | Henderson, Louis F. Early experiences of a botanist in the Northwest: The O'Neil Olympic Expedition, 1890. Paper presented at the Oregon Audubon Society, Spring. Extracts from a typescript in the University of Oregon library. |

| 1973 | Higley, Orte. The Higleys—1890. In Trails and trails of the pioneers of the Olympic Peninsula, comp. Lucile Horr Cleland, 178-84. Seattle: Shorey Book Store. |

| 1907a | Himes, George. First ascent of Mount Olympus. Steel Points, 159. |

| 1959 | Hitchman, Robert. Name calling. The Mountaineer, March, 6-19. |

| 1911 | Howay, Frederick W., ed. Early navigation of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Oregon Historical Society 12: 1-32 |

| 1907 | Humes, G. W. Journey to Mount Olympus. The Mountaineer, June, 11-12 |

| 1902 | Johnson, F. A. The Olympics and their elk: Recreation, March 191-93. |

| 1947 | Jones, Nard. Evergreen land: A portrait of Washington state. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. |

| 1860 | Kohl, J. G. Hydrography of the coasts and navigable waters of Washington Territory. Reports of explorations and surveys, to ascertain the most practicable and economical route for a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. Vol. 12. Book 1. N.p.: Thomas H. Ford, Printer. |

| 1937 | Lauridsen, G. M. and A. A. Smith. The story of Port Angeles, Clallam County, Washington: An historical symposium. Seattle: Lowman and Hanford Company. |

| 1981 | Majors, Harry M. and Richard C. McCollum, eds. The Press party photographs. Northwest Discovery, March, 138-62. |

| Mason County Journal (Shelton, Washington). | |

| 1890 | 2 May. Exploring the Quinault. |

| 1890 | 22 August. Mason County copper mines. |

| 1913a | Meaney, Edmond S. The Olympics in history and legend. The Mountaineer, no month, (Vol. 6), 51-55. |

| 1913b | ______. The story of three Olympic peaks. Washington Historical Quarterly 4 (no. 3): 182-86. |

| 1790 | Meares, John. Voyages made in the years 1788 and 1789, from China to the Northwest coast of America. London: Logographic Pre[s]s. |

| 1955 | Morgan, Murray. The last wilderness. Seattle: University of Washington Press. |

| The Mountaineers library, Seattle, Washington. Unaccessioned newspaper clipping file. | |

| 1907a | n.d. Mountaineers go for outing. |