|

OLYMPIC

Summary Prehistory and Ethnography of Olympic National Park, Washington |

|

II. REVIEW OF PREVIOUS ARCHEOLOGICAL RESEARCH

Introduction

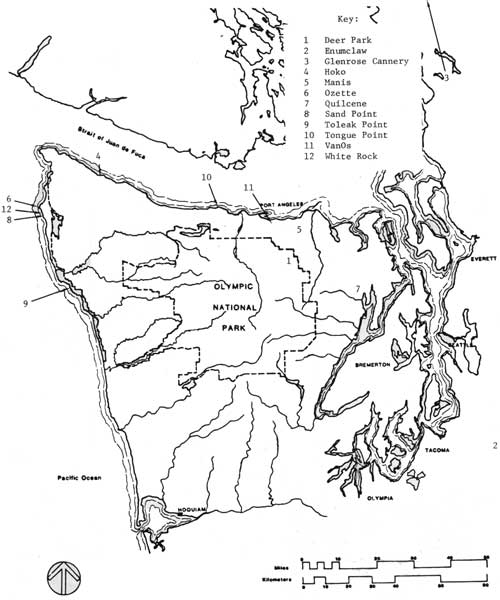

Aside from the narrow coastal strip, the archeology of Olympic National Park is virtually unknown. Therefore, the prehistory of the Park, as it is presently understood, is rather speculative and has been derived from a broad regional data base. Figure 2 shows the approximate locations of sites referred to in this report.

|

| Figure 2. Archeological Sites Referenced in the Text. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Despite the relative lack of data from the Park per se, the general trends evident in the broad outline of prehistory are indeed exciting. Those trends reflect changing human adaptations to an environment which was highly varied physiographically, rich in food resources and which presented its own unique set of problems.

Before examining those prehistoric trends, it is necessary to review the archaeology which has been done in the Park, as well as important research from elsewhere on the Peninsula.

Archeology Along the Coast

The published and unpublished archeological literature reflects a research bias which has favored coastal sites. The very dense vegetation of much of the Peninsula makes archeological survey and site detection extremely difficult, except along the coast. There, access is somewhat better and erosional agents have made cultural remains highly visible. For the most part, those remains are refuse deposits consisting largely of molluscan shell fragments, sea mammal bones, charcoal, and fire-cracked rock, all in a distinctively dark soil matrix. Most work has been undertaken since World War II and has been oriented toward understanding the time-depth, distribution and technology of the well-known Northwest Coast ethnographic pattern (see Summary Ethnography, this report).

After the initial work of Albert Reagan (1917), which consisted of test excavations and survey in the LaPush area, there was a thirty year hiatus in archeological research in the area. In the late 1940's, Richard Daugherty, then of the University of Washington, surveyed the coast between Capes Flattery and Disappointment.

The coast was surveyed again by University of Washington students in the mid-1950's (Stallard and Denman 1955). That study, which was funded by the National Park Service, encompassed the coastal area between the Ozette and Queets Rivers and included inland portions along the major streams emptying into the ocean. Stallard and Denman performed site survey and subsurface testing, and also interviewed native informants regarding aboriginal site locations. They documented seventeen archeological sites, eight of which were in Olympic National Park. Besides the archeological sites, they listed and located on maps sixty-four aboriginal sites which their native informants knew of. Twenty-seven were reportedly on Park land.

Limited archeological excavations were conducted at two coastal shell midden sites in Olympic National park and subsequently reported by Newman (1959) and Guinn (1962, 1963), graduate students at Washington State University. The small artifact assemblage collected from each site reflected late prehistoric and historic occupations and could offer little in the way of additional insight into the area's prehistory. Interestingly, however, Newman reported the existence at Toleak Point (45JF9) of an older, non-shell cultural component with associated chipped stone tools (1959:90), while Guinn noted, for the first time on the northern Washington coast, the presence of an iron tool in an apparently prehistoric cultural layer at the White Rock Village site (45CA30) (1962:17).

In the mid-1960's, intensive multidisciplinary investigations began at the large Ozette Village archeological complex (45CA24), portions of which are in Olympic National Park at Cape Alava. At Ozette, investigations were undertaken by Washington State University under the overall direction of Richard D. Daugherty. Initial work was directed toward trenching of the site area in order to determine the extent, nature and geochronology of the cultural remains there (Daugherty and Fryxell 1967). However, the discovery in 1967 of late prehistoric house remains buried and well-preserved under massive mud slides shifted the focus of research at Ozette. The Makah Tribal Nation became actively involved. In 1970, Washington Archaeological Research Center (WARC) and WSU investigators, again under the direction of Daugherty, began careful hydraulic excavation of the intact household remains, which included such normally perishable items as wooden structural members and artifacts, basketry and cordage. Field work continued until 1981. Thus, the primary research focus shifted from examination of the total cultural sequence at the site to the excavation, conservation and technological analysis of materials from the late prehistoric houses.

The Ozette Archaeological Project has greatly enhanced our understanding of the late prehistoric and protohistoric periods on the coast. The water-saturated cultural components at Ozette have yielded large artifact inventories, of which over 80% are wooden or plant fiber specimens. This contrasts markedly with the rather meager artifact assemblages found in the "dry" late prehistoric shell middens elsewhere on the coast (Wessen 1980b, 1981). Several individual theses and dissertations have resulted from the Ozette Project (c.f. Croes 1977, 1980; Ellison 1977; Mauger 1978; Gleeson 1980a, 1980b), interim reports have been issued detailing fieldwork and special analytical studies, and there have been a number of popular books and articles dealing with the site (Kirk 1974, 1978). Unfortunately, the earlier cultural components at Ozette have never been adequately reported, nor has there been any synthesis attempted which would tie together the many lines of evidence unearthed there.

More recently, research teams under the direction of Dale Croes have excavated a site located near the mouth of the Hoko River on the Strait of Juan de Fuca north of the Park. Work there commenced in the late 1970's and is not yet completed. Like Ozette, the Hoko River site has yielded normally perishable artifacts well-preserved in a water-saturated component, as well as a more typical "dry" midden component and associated artifacts (Croes and Blinman 1980). However, the materials from Hoko are primarily discarded refuse from a seasonal fishing camp as opposed to intact household assemblages, and are about 2000 years older than the late prehistoric remains from Ozette. Additionally, a relatively substantial lithic assemblage has been unearthed at Hoko, including hafted microlithic knives (Flenniken 1980). The research at Hoko will continue to expand substantially our understanding of earlier coastal sites.

Other potentially important earlier coastal sites have been tested by Daugherty and Gary Wessen and dated, but have not yet been reported in any detail in the literature (Wessen 1980b; 1981; personal communication 1982). One of those sites is located near Sand Point, and is within the boundaries of the Park's coastal strip; another site is on the Strait of Juan de Fuca, within 5 miles of the Park's northern boundary.

Archeology in the Interior

With the exception of one high elevation lithic site near Deer Park in the northeastern corner of the Park (see Bergland 1982), no known prehistoric archeological sites have been reported for the interior portion of Olympic National Park. This dearth of information is the result of: 1) lack of accessibility, 2) dense vegetation and rugged terrain, (3) the widespread belief, evident in both popular works and early archaeological reports, that aboriginal inhabitants of the Peninsula did not make appreciable use of the mountainous uplands, 4) lack of interest, and 5) lack of funding.

Systematic study of the interior began in 1977, when Wessen conducted reconnaissance of major river valleys in the western portion of the Peninsula. The objectives of that survey were to locate and document the many reported aboriginal river "village" locations. Several of the locations examined were within present Park boundaries.

The reconnaissance team discovered isolated artifacts (a projectile point, grooved "net stones", a shaped hammerstone, and two cortex spall tools), plus fire-cracked rock and charcoal, but nothing in a context suggestive of a habitation site. Wessen discussed the dynamic nature of the streams, the highly perishable late-prehistoric/early historic artifact inventory, limited accessibility and dense vegetation as probable reasons for the generally negative survey results (Wessen 1978).

Other cultural resource management efforts on the Peninsula have been undertaken recently, especially on the Olympic National Forest (Righter 1978; Barbara Hollenbeck, personal communication 1982). Those surveys have been largely unproductive in terms of locating prehistoric interior sites (Wapora 1980; Geo—Recon 1982).

Two important near-coastal sites have been investigated on the northeastern Peninsula. While not in the Park, their proximity to it warrants discussion here. An early stone tool site was excavated in 1971 by David Munsell, then Washington State Highway archeologist (Kirk 1978). That site, located east of the Park near Quilcene at the mouth of Hood Canal, yielded a lithics assemblage similar to what is known as the "Olcott Complex". Although no absolute dates were obtained, Munsell places the Quilcene site at 6000-8000 years before present (B.P.), based on comparisons with the Olcott "type-site" on the Stillaguamish River and similar dated assemblages in eastern Washington (Munsell, personal communication 1982).

The oldest known archeological site on the Peninsula is currently being investigated. That site is, of course, the Manis Mastodon Site south of Sequim, Washington. There, fossil bones and tusks were accidently unearthed in 1977 and brought to the attention of Richard Daugherty, Carl Gustafson and Delbert Gilbow, all of WSU. Hydraulic excavation of the fragile remains of the site has revealed several cultural layers ranging in age from 12,000 to 6500 B.P. The oldest bone-bearing levels contain the remains of mastodon, bison and caribou, plus a limited inventory of worked bone. More recent levels at the site contain worked wood, chipped stone projectile points, cobble spall tools and more worked bone.

The Manis site has contributed greatly to an understanding of the area's cultural time depth and paleoclimate. Work under the direction of Gustafson continues and should prove productive.

Discussion

It should be readily apparent from this section that the archeology of Olympic National Park has been hampered by dense vegetation, rugged topography, limited access and the lack of interest and research funds. Also, the slant or bias in most research has favored investigation of relatively recent coastal sites.

Other than the Manis and Quilcene sites, no interior or non-coastal sites have been investigated in any detail. The recently discovered Deer Park site represents the only known prehistoric archeological site recorded for the large interior portion of the Park.

Given those large gaps in the archeological record, both in time and space, the prehistory to follow must draw upon wider regional sources. The following section presents a general cultural sequence.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

prehistory_ethnography/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 03-Nov-2009