|

Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument Arizona |

|

NPS photo | |

Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument is a scientific treasure. Its deep canyons, mountains, and lonely buttes testify to the power of geological forces and provide colorful vistas. Paleozoic and Mesozoic sedimentary rock layers—relatively undeformed and unobscured by vegetation—offer a clear view for understanding the Colorado Plateau's geologic history. Geologic, geographic, and biological transitions give rise to the monument's astonishing ecological diversity. Here two geologic provinces meet, the Basin and Range and the Colorado Plateau. Here also two ecoregions meet, the Mojave Desert and Colorado Plateau. Within these ecoregions three floristic provinces converge—Mojave Desert, Great Basin, and Colorado Plateau—creating diverse assemblages of plant and animal communities. Geologic variations coupled with elevation changes, ranging from 1,400 feet above sea level near Grand Wash Bay to over 8,000 feet on Mt. Trumbull, result in a variety of desert, shrubland, and montane habitats. Cooler conditions found in higher-elevation ponderosa pine forests provide habitat for wild turkeys, northern goshawks, and Kaibab squirrels. Middle elevations feature pinyon-juniper forests and sagebrush that support pinyon jays, Great Basin rattlesnakes, and mule deer. Low-elevation Mojave Desert features creosote bush, Joshua trees, Gila monsters, Gambel's quail, and desert bighorn sheep. Rare springs with life-giving water are hotspots hosting distinctive plant and animal life.

It is hard to imagine how people survived in this harsh land, but the evidence of tenancy testifies to human perseverance. Occupation began 12,000 years ago with large-animal hunters followed by hunter/gatherers. About 3,000 years ago the introduction from Mexico of corn and, later, squash and beans allowed the people to settle into small villages. Each group left clues like pecked and painted rock images, home sites, tools, and quarries that give us some insight into their lives. Southern Paiutes living in this area at the time of Euro-American contact in 1776 still live in the Colorado Plateau region. Remnants of early homesteads punctuate the landscape, expanding its rich human history, a vital dimension of the area's character.

A TRANSITIONAL LANDSCAPE

DESERT WASH

The Mojave, driest of all North American deserts, gets fewer than 10 inches of

rain a year. Snaking across this arid landscape, scoured desert washes carry the

runoff after monsoon rains. Desert tortoises actively forage after these

refreshing storms. Deep-rooted plants grow along the edges and on islands in the

washes, providing black-tailed jackrabbits with shady hiding places.

JOSHUA TREE FOREST

Joshua trees are characteristic Mojave Desert plants that grow up to 40 feet

tall. Haphazard, prickly branches give many animals shelter, a food source, or

nesting materials. As many as 25 bird species nest in Joshua trees: Scott's

orioles hang nests from branches; other birds build nests in foliage; and

northern flickers peck nest holes in the trunks. Toppled trunks house insects

that provide a food source initiating a complex food web.

MOJAVE DESERT SCRUB

This community's spiny, succulent plants denote desert to most people. In rainy

periods barrel cacti store water in their vault-like bodies, safe under myriad

spines. Surviving long periods of no rain, they live up to 130 years.

Rock-dwelling chuckwalla lizards also use their bodies as canteens—and as

larders—during wet periods. They can also wedge themselves into rocks and

puff up so much that predators can't pull them out.

SAGEBRUSH STEPPE

Typical Great Basin communities are sagebrush steppe—a semi-arid

plain—and pinyon-juniper woodland that cover much of the national monument.

You will drive for miles through this multi-hued landscape of sagebrush, shrubs,

and short grasses. Big sagebrush is most common, but there are several other

species, too. The adaptable coyote hunts rabbits and other small animals that

hide in the shrubs.

PINYON-JUNIPER WOODLAND

Pinyon pines and junipers grow on mountainsides and plateaus above the steppe.

Although junipers can live 300 to 400 years, they only grow 20 or 30 feet tall.

Slow-growing pinyon pines germinate beneath a nurse plant and when mature

produce nutritious seeds that were once a vital food source for native people.

Birds and rodents like these tasty pine-nut seeds and help to plant new trees

when they cache them in the ground for winter food.

PONDEROSA PINE FOREST

Cooler, higher, and with more rain, the Colorado Plateau ecoregion supports

ponderosa pines with associated Gambel oak, New Mexican locust, and

serviceberry—home to turkeys, Kaibab squirrels, mule deer, and goshawks.

Ponderosa pines live to 600 years and can grow over 90 feet tall. Their

orange-brown bark smells like vanilla. Periodic burning is essential to

maintaining the health and vigor of ponderosa pine forests.

INDIANS

The 1776 Escalante-Dominquez expedition found Southern Paiutes gardening,

hunting, and gathering. In rabbit skin robes, this circle dance ceremonial group

celebrates their ties to the land and animals.

SETTLERS

Beginning in the 1870s Mormon settlers, miners, loggers, and ranchers built

homes here and struggled to raise families and survive in this remote country.

Their descendants still ranch in the monument.

LOGGING

Local stands of ponderosa pine provided building materials for early settlers'

cabins and homesteads and for Mormon building projects. No economically

significant lumbering began until 1876.

COPPER MINES

After an abortive gold rush, copper mining took hold in 1873. Of several mines,

the Grand Gulch was most important. Mules packed in tools and supplies until a

wagon road opened to St. George, Utah, in the 1870s.

CATTLE RANCHING

Livestock grazing has been part of Arizona Strip culture since the 1850s. It is

still part of the monument's multiple-use management where authorized. Few

full-time residents live in this remote area today.

PRESERVATION

Established by presidential proclamation in 2000, this remote national monument

includes an array of scientific, natural, cultural, and historic features and

opportunities to experience rugged recreation.

PAKOON SPRINGS

Springs or seeps are oases in arid landscapes. Wherever water flows, a green

pocket sustains diverse and abundant collections of plants and animals.

Impounded now, Pakoon is the monument's largest spring.

TASSI RANCH

Tucked in rocky hills beside a flowing spring, a rustic stone house and other

ramshackle structures paint a vivid picture of life on a cattle ranch in the

1930s and 1940s.

GRAND GULCH MINE

An adobe smelter was built around 1878 to avoid hauling unprocessed ore to a

distant railhead. Success was partial: slag was later shipped for more

processing. In the early 1900s, 75 to 80 people lived on-site.

WHITMORE OVERLOOK CANYON

A rough dirt road winds into a valley and ends at an area with spectacular views

of Grand Canyon and the Colorado River.

HELLS HOLE

Hells Hole is an amphitheater eroded from reddish and white Moenkopi Formation

rock.

NAMPAWEAP

A ½-mile trail takes you to one of the largest petroglyph sites on the

Arizona Strip. Hundreds of images pecked into the surface of basalt boulders

offer clues about the lives of early native residents.

A MONUMENTAL PARTNERSHIP

Here, in over a million acres of vast, remote, and sparsely developed landscapes, the Bureau of Land Management and National Park Service have embarked on a monumental joint venture—to conserve in perpetuity the cultural and natural features and values, and wondrous solitude, in this place where remoteness has underwritten the survival of its strikingly wild character. The monument encompasses the lower Shivwits Plateau, an important Colorado River and Grand Canyon watershed, and contains countless biological and historical values of the Arizona Strip, so called because the Grand Canyon isolates it from the rest of the state.

Congress has designated four areas of the monument for protection as wilderness under the National Wilderness Preservation System Act. Special regulations apply in designated wilderness. Please check at the information center.

PLANNING YOUR VISIT

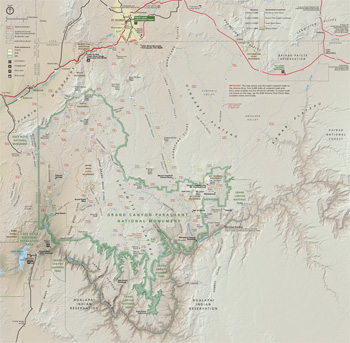

(click for larger map) |

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and National Park Service (NPS) invite you to experience the 1,050,963-acre Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument. No permits are required for public recreational use. There are no facilities or gasoline available in the national monument.

There is NO cell phone service in the monument.

An Interagency Information Center in St. George, Utah offers exhibits, publications, and maps. Desk staff can answer questions and update you on road conditions. Weekday hours are 7:45 a.m. to 5 p.m., Saturday 10 a.m. to 3 p.m., closed on Sunday. There are several ways to enter the monument, but be aware that ail access is by rough dirt roads. Before entering the monument procure the BLM Arizona Strip Visitor map or appropriate topographical maps at the Interagency Information Center in St. George, Utah, or at Pipe Spring National Monument, located on Arizona Route 389, 15 miles west of Fredonia, Ariz, (open 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily).

HIKING AND BACKPACKING

Mt. Trumbull, Mt. Dellenbaugh, Nampaweap, and Grand Wash Cliffs Wilderness

trails are the only semi-maintained trails within the monument. All other hiking

is on routes that are not marked or that require bushwacking through dense brush

or rugged terrain.

REGULATIONS AND SAFETY

Before entering the monument you must be prepared for adverse conditions and

isolated circumstances. Potential hazards include the rough, unmarked back

roads, poisonous reptiles and insects, extreme heat, and flash floods. Drive

only on existing roads. High-clearance vehicles are recommended.

Also observe these regulations and safety precautions:

• Take one, preferably two, fullsize spare tires.

• Do not rely on cell phones for emergencies.

• Tell someone where you are going and when you will return. If you break

down, stay with your vehicle.

• Take extra food, water, and enough clothing to accommodate weather

changes.

• Motorized vehicles must stay on existing roads—no vehicles are allowed in

wilderness areas.

• All operators and vehicles, including ATVs, must be licensed on county

and National Park Service roads.

For more information about the National Park System visit www.nps.gov. For more information about the Bureau of Land Management visit www.blm.gov.

Source: NPS Brochure (2007)

|

Establishment Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument — January 11, 2000 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Accessibility Self-Evaluation and Transition Plan Overview, Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument, Arizona (November 2017)

Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plant Flora of Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument: Phase II Report (Terri Hildebrand and Walter Fertig, May 1, 2012)

Annotated Vascular Plant Database, Grand Canyon Parashant National Monument: Phase 1 Report (Walter Fertig, August 28, 2010)

Arizona Explorer Junior Ranger (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Arizona Strip Visitor Map (BLM, 2016)

Assessment of Rangeland Ecosystem Conditions in Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument, Arizona U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2020-1040 (Michael C. Duniway and Emily C. Palmquist, 2020)

Backroads Bastion: Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument Administrative History (Theodore Catton and Diane L. Krahe, December 2018)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory Level II: Waring Ranch (2003)

Fact Sheet, Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument (December 10, 2015)

Foundation Document Overview, Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument, Arizona (January 2016)

Grand Canyon National Park-Grand Canyon/Parashant National Monument Vegetation Classification and Mapping Project NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/GRCA/NRR—2015/913 (Michael J.C. Kearsley, Kass Green, Mark Tukman, Marion Reid, Mark Hall, Tina Ayers and Kyle Christie, February 2015)

Green Springs, Historic American Landscapes Survey (Michael R. Harrison, undated)

Historic Preservation Report: Condition Assessment and Preservation Recommendations — Grand Gulch Mine and Pine Well Ranch, Parashant National Monument (Mark L. Mortier, September 30, 2003)

Horse Valley Ranch, Historic American Landscapes Survey (Michael R. Harrison, undated)

Junior Arizona Archeologist (2016; for reference purposes only)

Junior Ranger Handbook, Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Long-Range Interpretative Plan (August 2012)

Natural Resource Condition Assessments for Six Parks in the Mojave Desert Network NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/MOJN/NRR-2019/1959 (Erica Fleishman, Christine Albano, Bethany A. Bradley, Tyler G. Creech, Caroline Curtis, Brett G. Dickson, Clinton W. Epps, Ericka E. Hegeman, Cerissa Hoglander, Matthias Leu, Nicole Shaw, Mark W. Schwartz, Anthony VanCuren and Luke Z. Zachmann, August 2019)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Greater Grand Canyon Landscape Assessment NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/GRCA/NRR-2018/1645 (Sasha Stortz, Clare Aslan, Tom Sisk, Todd Chaudhry, Jill Rundall, Jean Palumbo, Luke Zachmann and Brett Dickson, May 2018)

North Rim Homelands: An Ethnographic Overview and Assessment Relating to Tribes Associated with Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument (Douglas Deur, Rachel Lahoff and Deborah Confer, 2014)

Paiutes, Mormons, and Mericats: A History of Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument Draft (Frederick L. Brown, 2009)

Paleontological Resource Inventory (Public Version), Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/PARA/NRR-2021/2338 (Justin S. Tweet, Holley Flora, Sumner Rose Weeks, Eathan McIntyre and Vincent L. Santucci, December 2021)

Photographic Guide to the Bryophytes of Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument (John Brinda, April 2011)

Pine Ranch, Historic American Landscapes Survey (Michael R. Harrison, 2011)

Plants of the Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument (July 2003)

Proclamation 7265—Establishment of the Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument (William J. Clinton, January 11, 2000)

Records of Decision and Resource Management Plan/General Management Plan, Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument (Bureau of Land Management/National Park Service, February 2008)

Records of Decision and Resource Management Plan, Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument (2010)

Southern Paiute Cultural History Curriculum Guide: Supplemental Lessons for Grades 6-9 (Joëlle Clark, September 2010)

Southern Paiute - Parashant Bulletin (Volume 1, July 2013)

Tassi Ranch, Tassi Springs, Historic American Landscapes Survey (Michael R. Harrison, 2010)

The Oasis (Mojave Desert Network)

Unav-Nuqauaint: Little Springs Lava Flow Ethnographic Investigation (Kathleen Van Vlack, Richard Stoffle, Evelyn Pickering, Katherine Brooks and Jennie Delfs, September 2013)

Waring Ranch, Historic American Landscapes Survey (Michael R. Harrison, 2011)

Yanawant: Paiute Places and Landscapes in the Arizona Strip — Volume One of The Arizona Strip Landscapes and Place Name Study Final Draft (Richard W. Stoffle, Kathleen Van Vlack, Alex K. Carroll, Fletcher Chmara-Huff and Aja Martinez, December 15, 2005)

Yanawant: Paiute Places and Landscapes in the Arizona Strip — Volume Two of The Arizona Strip Landscapes and Place Name Study (Diane Austin, Erin Dean and Justin Gaines, December 12, 2005)

Additional Documents can be found at this location

para/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025