|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Park and Recreation Structures |

|

TENT AND TRAILER CAMPSITES

SWEEPING CHANGE in travel and the camping habits of tourists is in process that must shortly force revisions of present day park campground lay-outs if these are to continue functioning to serve campers and preserve parks from misuse. The deus exmachina is the automobile trailer or house car. So popular has this accessory to more abundant travel become that estimates from some parks indicate that one camper out of three has already "gone trailer."

Current production schedules of manufacturers of this equipment evidence that the end is not yet. Although the saturation point is unpredictable, there are indications that taxation and regulation may eventually place limits on the growth of trailer popularity. While the current sharp up-curve of trailer production may level off, as the graph-makers phrase it, at some not distant time, there exists an immediate and pressing need for the suitable accommodation of trailer campers in or near our parks which may not be disregarded. It is a problem to be met squarely and adequately, without lag behind demand and yet certainly without feverish overbuilding based on speculation alone.

It is not unanimously agreed that trailers should be admitted to parks. Some feel that it would be better to ban them entirely and leave their accommodation to private enterprise beyond the park borders. Reasons advanced in support of this opinion are the traffic hazard of trailers on narrow park roads, their destructive effect on light roadways and campsites and, where the camp lay-out must be compact, the likelihood of slum conditions developing and spreading to infect in more or less degree the park area beyond the campground.

It is not here sought to prove that trailer camps belong or do not belong in parks. Probably there are areas where their introduction would be grave error, and others where their presence would not have adverse effect. The intent herein is rather to consider what a trailer campsite in a park can be, once it has been determined that a trailer campground may properly be undertaken on a given area.

In the pamphlet, "Camp Planning and Camp Reconstruction", issued by the United States Forest Service, Dr. E. P. Meinecke analyzes principles of camp planning for automobile-and-tent campers. Until the advent of the trailer, developments based on these principles served to bring order to camping activities in natural parks and to preserve natural aspect without hobbling campers' use and enjoyment of a camping area.

Basic in this campsite concept is a short parking spur, taking off from a one-way road at a readily negotiable angle, and bounded by naturalized barriers defining the parking space and confining the camper's automobile therein. Supplementing principle is a logical grouping of tent site, picnic table, and fireplace in suitable relation to the parked automobile, existing tree growth, and prevailing winds. Finally, a screening of undergrowth around the fringe, to limit and give a desirable privacy to the individual campsite, completes the picture. This arrangement when properly executed met well the needs of the tent camper. He could head into his allotted parking spur, pitch camp, and back his car out with ease whenever he wished to do so.

But when the camper decided to live in a trailer instead of a tent, he discovered that the campsite, ideally arranged for tent camping, was far short of ideal for a trailer. After he had driven his car into the parking spur, dragging his trailer behind him, he found his tow-car stymied by the trailer in the rear and by barriers ahead. In order to "go places" on casual errands he must either back out trailer and all at great inconvenience, or try to hurdle, or worm his way between, barriers in front. The results were certain destruction of the camp site and probable damage to his car.

Vainly seeking a more workable solution, he might then make a fresh start and attempt to back the trailer into the parking spur in order that his automobile might be free for daily comings and goings. If it be recalled that the parking spur for the tent camper's automobile was laid out to be easily swung into head-on from a one-way road, the sharp angle will be appreciated as correspondingly unnegotiable with an unwieldy trailer leading off in a reverse approach. Further, this backing operation creates both obstruction and hazard to traffic that cancel the benefits of a one-way road system.

The more perfectly suited an object, idea, or plan to a given set of conditions, the less readily adaptable it is to different conditions. The very perfection of the ideally executed tent campsite seems to doom it to considerable revision if it is to be made convenient for the trailer.

MOST ADVANTAGEOUS for the head-on parking of the tent camper's automobile was a spur approximating the familiar 45-degree angle parking of some city streets. Best suited to the backing-in of tow-car-and-trailer, if backing is to be tolerated, is this same spur, but only if approached from the opposite direction. It is quite possible that many existing spur campsites, laid out on a one-way loop road, can be made more receptive to tow-car-and trailer occupancy by the simple expedient of reversing the direction of travel on the camp road and increasing the length of the parking spurs. The results of an intelligent remodeling of certain old campgrounds can be satisfactory in considerable degree, although there will remain the hazards potential in backing a trailer.

Opinion about the difficulty of this operation is divided. There are those who maintain it is no trick at all and that it may be utterly disregarded as a factor in campground lay-out. Others are just as certain that backing a trailer, particularly into a parking spur laid out to minimum requirements, calls for much skill and long practice, and that only camp lay-outs which eliminate all necessity for the backing operation are sufferable. It would seem that the very existence of the latter opinion must demonstrate that backing a trailer is not a trifling task. Those who have observed on the highways the ineptitudes of some citizens for driving a single car forward will sense the havoc that can lurk in their maneuvering a trailer train in reverse. It is felt that the exploration here of alternatives of the spur, which can eliminate in future campground development all necessity for backing trailers, will be tolerated, if not actually welcomed, by serious readers.

There are two alternatives to spur parking. Herein these are dubbed the "bypass" and the "link."

The bypass is any arrangement permitting the trailer camper to drive tow-car-and-trailer off the traveled camp road, park, and drive onto that same road again without backing. In its simplest expression it is merely a defined widening of the camp road to allow tow-car-and-trailer to park out of the traveled lane. In its elaborations an island is created between bypass lane and camp road. This may be compact or extended, formal or informal in plan, screen-planted or not, all as influenced by the distance it is elected to allow between points of take-off from, and return to, the camp road. The bypass may be surfaced like the camp road or merely graded. Where conditions of soil and climate permit, it may be developed as a well-defined grass-grown wagon trail and not as a roadway, particularly where an island provides physical separation. A range of bypass treatments is shown among the plates which follow.

The link is any arrangement allowing the trailer camper's rolling stock to be driven off a traveled camp entrance road to suitable and sufficient parking whence it can be driven onto another roughly parallel camp exit road without any necessity of backing. Variations of the link result mainly from the distance between the entrance and exit camp roads. This may be as little as 50 feet or, owing to affecting topographical conditions or desire for greater privacy, 100 feet or even more. Under favorable conditions the link lane, like the bypass lane, may be in the nature of a well-defined grass-grown wagon trail, rather than a roadway, to a preservation of natural aspect and a saving in development cost. Variations of link campsite lay-outs are presented among the plates.

Included in the diagrams which seek to show the gamut of campsite possibilities more or less receptive to tow-car-and-trailer parking are several spur parking arrangements. None of these requires the extremity of awkward backwards-maneuvering demanded by the tent camper's parking spur when appropriated to trailer use. Wherever there is a disposition to accept a limited backing of trailer, these spur parking arrangements will receive interested consideration for their many points of merit. They make possible a maximum number of campsites per acre. This is an advantage where a more generous space allotment per campsite and the resultant sprawling campground will mean the dissipating of high scenic or wilderness values. The compactness of these spur sites makes for economy where the campground development contemplates the provision of water, electric, and perhaps sewer connections on every campsite, especially where the site is underlaid with rock. But only a generally level terrain, uninterrupted by any natural features which must be preserved and protected, will lend itself to a geometric, space-conserving grouping of minimum campsites. There are numerous factors acting to sabotage an arbitrary decision to create a campground providing a maximum number of campsites per acre. Very generally, and it is believed fortunately, some of these influences will operate to prevent trailer campgrounds from becoming too formal in lay-out and too conserving of space to be attractive.

First of all, there is not an abundance of terrain over which it is feasible to construct straight, parallel roadways in the pattern of suburban subdivisions. More often than not it will be necessary to build curving roads in adaptation to contours, and the results will be a pleasing informality and a certain welcome "slack" in space use.

Although there may be very grim determination to be ruthless in sacrificing every tree that chances to be within the blueprint confines of the parking spurs and lanes, it is difficult to believe that there will not be a pardonable warping of geometric perfection in order to preserve especially desirable tree and plant growth, with coincident retention of camp-ground assets and some easing up of space limitations.

Then there is that human trait that stubbornly persists in some of us—a desire for privacy in some degree. Ringed in by the most ideal of tree and undergrowth screening, the minimum campsite has at best only the illusion of privacy. If soil or climate is such that effective vegetative screening between campsites is sparse or lacking, greater distances in lieu of foliage barriers may be adopted to real advantage.

In a park wherein primary scenic splendor might be coupled with an extensive, unspectacular buffer area, lacking competing use claims, there will be less reason to compress the areas sacrificed to the modifying effects of camping. If a sizable park is magnificently forested through its entire extent, and camping is determined to be permissible, a camping area will most certainly not be completely cleared for the dubious benefits and close quarters of a treeless gridiron lay-out of minimum campsites.

Among the influences on the other hand tending to compress campground lay-out, most important is the immunity from trespass rightfully established by the presence of outstanding natural values. Another potent factor in this direction is the extent to which it may be determined to provide utilities water, electricity, and sewerage. Obviously, installation costs of these increase in direct ratio to the distances involved.

THE EXTENT to which campground equivalents of public services and utilities—water, electricity, and sewers should be made available in trailer camps is much debated. A tent campground has long been felt to be suitably equipped if safe drinking water were provided not more than 200 feet, toilets not more than 400 feet, and washhouse and laundry not more than 1,500 feet distant from any individual campsite. Should not these same facilities provided within similar maximum distances be satisfactory in a trailer camp? Is it really desirable to go further and provide on each individual campsite so many of the refinements of a hotel room that camping fees must climb to virtual competition with hotel rates—to make vacationing out-of-doors so de luxe as to pass beyond the economic range of the majority?

Surely in our parks we should cling tenaciously to a policy of "live and let live" with respect to human beings. This enlightened attitude has inspired our policy with respect to native flora and fauna in parks. Why not accord man the dignity of treating him as a native faunal species and permit him to vacation in a park with some lingering trace of the simple style which he could once enjoy—and could afford?

It is not incumbent upon park authorities to give aid and comfort so abundantly to the nomad that he can only be dislodged from the campground by the first frost. Nor is there any apparent gain to derive from depriving camping of the last semblance of adventure and the primitive.

Where site conditions make for moderate installation costs, it would not be unreasonable to go so far as to provide a drinking water tap adjacent to every campsite, whether laid out for tent or trailer.

It would be a great convenience certainly to the trailer camper if he could plug into an electric connection on the campsite and tap park current during his stay. If lighting only were involved, a flat rate per day could fairly cover the cost. But because some trailers are equipped with electric stove, iceless refrigerator, electric iron, electric heater and electric whatnot, is it good business to furnish electric current except by a coin meter? And the camp management, before electing to become an electric service distributor on such a basis, may well ponder the abuses, short circuits, blown fuses, and general distress potential in the nondescript equipment which will be driven into a park.

A campsite waste connection into a sewerage system might also prove convenient to the owner of a de luxe trailer. But would trailer owners generally be truly grateful for the step-up in camping fees to result from the capital and maintenance costs involved in making this convenience available? Doubtless the campground operator for his part would be recurrently, and more than mildly, annoyed by some of the abuses to which this little utility gadget would be heir.

Park planners should not be stampeded into a wholesale introduction of more and more of the complexities of urban living into vacationing out of-doors. There is every reason for proceeding cautiously with campsite refinements at least until such time as there comes into being a considerably greater degree of standardization of trailer equipment than prevails today. Sewage disposal for individual campsites certainly, and electric service possibly, are public utility fields where angels might at this writing fear to tread. Shall we then rush in?

WHERE CAMPGROUNDS IN PARKS offer some camp sites suitable only for tent camping and others devised for trailer accommodation, and when capacity or near-capacity occupancy is the rule, the troubles of the operating staff can be very complicated indeed. Checking the registering camp ems' equipment and assigning a campsite receptive to it consumes considerable time. There are occasions, with relatively more in prospect, when the trailer campers knocking at the gate exceed the number of campsites laid out for trailer use. There may be many campsites vacant which, laid out as tent campsites, cannot be negotiated by trailers. It is submitted that a lay-out of camp sites each of which is suitable for either tent or trailer occupancy is an ideal solution.

The trailer camper, be it remembered, will usually have no reason to pitch a tent. He will not always resort to cooking on an outdoor camp-stove or fireplace. Of the several units requisite to the complete tent camp menage, the table and bench combination probably will be used most by the trailer camper. Regardless of these facts, none of these campsite accessories should be omitted from the ideal campsite. Although, in general, the trailer camper cannot use the tent camper's spur site without great inconvenience to himself and eventual disaster to the site, the tent camper on the contrary can make convenient use of any trailer campsite without resulting dam age. The adaptability of trailer lay-outs to both tent and trailer use means 100 percent flexibility. It dissolves the camp operator's nightly nightmare of speculation as to how many campers-with-this-kind-of-equipment and how many campers-with-that-kind-of-equipment may register. Where campsites accommodating all corners are provided, the varying ratio of trailers to tents in an area need not be the disturbing concern that it now so often is.

The same obstacles, obstructions, and barriers needed to define the outlines of individual tent campsites and to keep the tent camper's automobile from encroaching upon parts of the campground where its free circulation would tend to injure plant life are likewise needed in connection with trailer campsites. Where there is a disposition to forego a maximum number of campsites per acre in favor of preserving desirable plant and tree growth, the principles of preservation by naturalizing transplanted rocks and large down timbers are especially applicable. Far too many campgrounds look as though a five-ring circus only yesterday had played to a capacity crowd on the site. The only safeguard against such threadbareness lies in providing obstructions and barriers on an effectual scale. Unfortunately, interpreters of the technique of preservation by means of obstructions and barriers have generally failed in the past to achieve a truly effectual scale. Their manipulations of peewee pebbles and saplings to pass for the rock and down timber barriers of the text and their consternation at the inadequacy of these are not without humor.

In the drawings that follow it is attempted to delineate possibilities for campsite lay-out receptive to the tow-car-and-trailer and making for the pleasure and comfort of the camper. Coincidently, protection of natural values and of the sensibilities of the park patron-at-large has been sought by one or the other of two theories of approach. One is to allocate a minimum space for the individual campsite and achieve a compactly geometrical arrangement of campground regardless of the ensuing despoliation of natural values over the limited area appropriated. The other approach acknowledges and preserves all such natural assets as forest cover, screening undergrowth, rock outcrops, and natural contours, and results in a more or less sprawling, informal campground that affects a greater area but modifies it in a lesser degree. Either theory has its points, and only a careful survey of the affecting site factors can determine which of the approaches, or what stage of compromise between them, is most appropriately adopted in a particular instance.

The drawings show one-way camp roads 10 feet wide and two-way camp roads 16 feet wide. In the case of either there should be an additional 3 feet to the center line of the gutter. Parking spurs, bypasses, and links are shown 10 feet wide. The minimum space allotment for an individual campsite is largely governed by the minimum turning radii of tow-car-and-trailer.

It will be seen that, because a majority of trailers have doors on the right hand side, flexibility in the grouping of some of the campsite lay-out types is limited. Some are adaptable only to the left side of a camp road, others only to the right. Unless a type adjustable to both sides of a road is used, left hand and right hand types must be selectively combined where development on both sides of a camp road is projected.

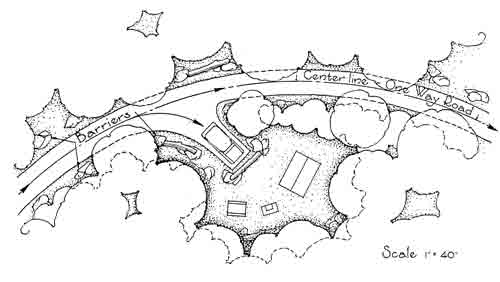

Immediately below is a lay-out illustrative of the lack of receptiveness to tow-car-and-trailer characteristic of the typical tent campsite—a dangerously awkward condition which, in the lay-outs presented by the plates following, it has been sought to avoid.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

park_recreation_structures/part3a.htm

Last Updated: 04-May-2012