|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Park Structures and Facilities |

|

BARRIERS, WALLS and FENCES

IF MAN COULD bring to his creations in natural parks, the protective coloration that Nature bestows on wildlife, with how much more harmony he would endow his trespasses! One particularly longs for this quality in barriers, herein considered to embrace obstacles and obstructions to automobile travel, stone walls and wood fences, guard rails and retaining walls. These are unavoidable necessities in practically all parks, and are generally so extensively required that any treatment short of the most skillful can become a source of quick contamination to natural beauty into the farthermost reaches of the area.

It is not to be denied that there sometimes exists in natural areas need for barriers that must forego protective coloration to shout immediate and forceful warning of danger ahead, particularly to the motorist. Barriers and obstructions that have as their primary objective being seen for the purpose of preventing traffic accidents, are not to be laughed off. They are an acknowledged if unwelcome necessity even in parks, and our public highways provide innumerable examples of precedent more or less effectual in purpose and construction. To create barriers that shout a warning is no trick at all. It is much more difficult to determine at exactly what locations on park roads a barrier having this function is requisite and tolerable. To provide within a given park area neither one too many nor one too few barriers having this primary function is both the problem and the solution. It should be studied in the light of the accepted tenet that park roads exist for leisurely automobile travel only, and with coincident appreciation of the fact that speed of traffic and need for cautionary and protective barriers relate to each other in some geometric ratio. Resultantly we should find in parks fewer blatant barriers than the public highways require, and a preponderance of the unobtrusive barrier treatment.

Barriers in natural parks can spread the blight of man's destructiveness with greater speed and to greater distances than any other instrument of his devising—save perhaps matches. For this reason they deserve to be planned with thoughtful care, and to be developed and constructed with ever alert willingness to adjust the predetermined treatment to serve best the varying backgrounds and conditions actually encountered in the field. The contrary approach, the attempt to warp conditions of site to some blueprint treatment of barrier or retaining wall, usually leads to disaster. Natural quality is so ready to vanish; artificial quality so prone to persist.

Barriers of stone have one basic advantage over barriers of wood. Stone is the more permanent, a fact which often predisposes its selection as the material for use. The claim of permanence, however, should not alone determine the choice of stone over wood; each must be further considered in the light of its native suitability. Stone imported into park areas to which no stone is native, seems always inappropriate. Stone imported into park areas to which a different and perhaps unworkable kind of stone is native, will demand the most skillful ingenuity in any effort to make the importation appear reasonably at home. There are certain regions where native stone suitable for building is not present, yet the landscape is of definitely stony character. Here barriers of imported stone can be made effective when artfully contrived. But more often than not, unless barriers can be produced from native stone, it is more reasonable to waive the advantage of greater permanence and make use of wood. Timber for barriers in some localities will offset comparative lack of permanence through native abundance and consequent greater suitability and economy. For wooded areas, regardless of stone supply, there are those who cast their votes in favor of wood, usually log, barriers, which can be made sturdy and unobtrusive, and are far from short-lived.

When neither wood nor stone can stake a valid claim to being native, or appearing to be native to a region, the attributes of the area for park purposes may be logically challenged. This premise allowed, we are assured that either wood or stone will appropriately serve as material for the barriers we may require in any tract of true park potentialities. The problem then becomes one of intelligent use of whichever material Nature's bounty indicates.

Among possible barrier constructions are some which when broken are more easily repaired than others. These will be favored by the park technician wherever the limiting of maintenance costs must be considered. Barriers designed with wood rails that build into stone piers usually require an excessive amount of labor when replacement of a broken rail becomes necessary. It is possible to detail the customary low guard rail of the parking area so that when one rail is broken the adjoining sections are unaffected either by reason of the accident itself or the ensuing operation of replacing the broken member.

Of particular import are the stretches of wall or fence that adjoin the entranceway. Unless these are to be completely planted out, something of the flavor of the entrance structures should be given them. The stone wall so typical of New England, New York, and Pennsylvania, and the rail fence once so widely distributed through the Middle West have the advantage of long familiarity and deep significance to many of us. Because they bring subconsciously to mind the very values that parks seek to recapture—open spaces, unspoiled Nature, release from cramped and artificial existence—they might well serve as a far more useful instrument than they have served to date in the hands of park planners.

In his well-presented "Camp Planning and Camp Reconstruction," issued by the United States Forest Service, Dr. E. P. Meinecke discusses the choice and use of obstacles, obstructions and barriers in relation to the principle of camp planning that has become widely known and accepted as the "Meinecke Plan." So much on the subject of barriers therein contained is applicable to their proper use in parks, beyond the confines of camp sites, that Dr. Meinecke is quoted here in part.

"It must not be forgotten," Dr. Meinecke writes, "that even the best of law-abiding citizens, when he is torn loose from the accustomed and accepted restrictions of town life, does not instinctively know what is permitted and what he is expected to avoid. . . .

"Obstacles and barriers must, therefore, be of such a nature that he immediately reacts to the directions as expressed by the placing of obstacles. Small rocks are too easily overlooked by the driver of the moving car. They do not look dangerous, and they are too easily moved. Logs of small diameter offer no obstruction at all, and their use is a waste of effort and expenditure.

"The size of rocks and logs to be employed is determined by the deterrent effect they produce upon the driver. Rocks should be partially embedded in the soil. They appear more natural and more solid than rocks placed merely on the surface. The size of the visible part of the rock is reduced by embedding, and this decrease in deterring mass must be taken into consideration in the choice of the rock employed. . . .

"It is neither necessary nor desirable to outline roads or spurs with rows of regularly spaced rocks. . . Regular rows look unnatural. . . .

"The use of logs to serve as barriers and guides along roads and parking spurs is, in general, much cheaper than the hauling and digging of boulders. On the other hand, logs and pole fences are far less permanent. In our wild forests the ground is often strewn with down trees which can be used for this purpose. Large logs lying on the ground will act as barriers for a long time, even if they decay. . . .

"When wood is used for barriers the plain, natural log, placed in such a way that it gives the appearance of having fallen where it lies, is with out doubt much preferable to the artificial fence . . . .

"Cedar logs are far more durable than pine. Fir is the least to be recommended. . . . When logs are used at all they must be substantial."

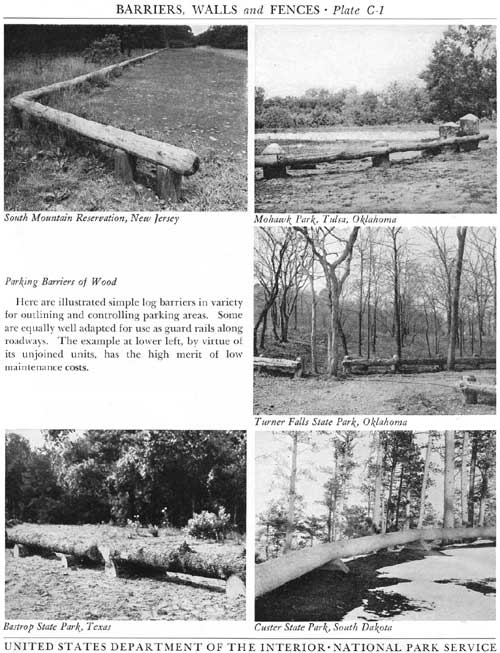

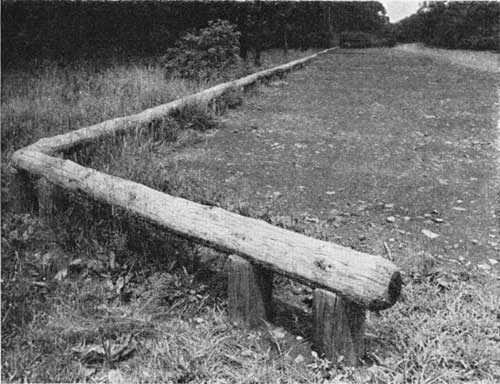

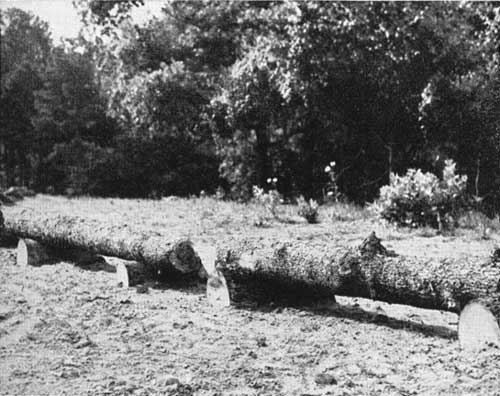

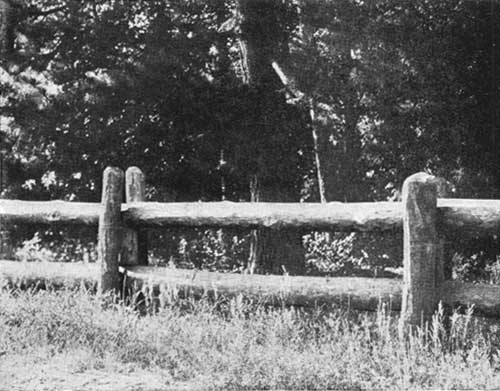

Parking Barriers of Wood

Here are illustrated simple log barriers in variety for outlining and controlling parking areas. Some are equally well adapted for use as guard rails along roadways. The example at lower left, by virtue of its unjoined units, has the high merit of low maintenance costs.

|

| Plate C-1 (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| South Mountain Reservation, New Jersey |

|

| Mowhawk Park, Tulsa, Oklahoma |

|

| Turner Falls State Park, Oklahoma |

|

| Bastrop State Park, Texas |

|

| Custer State Park, South Dakota |

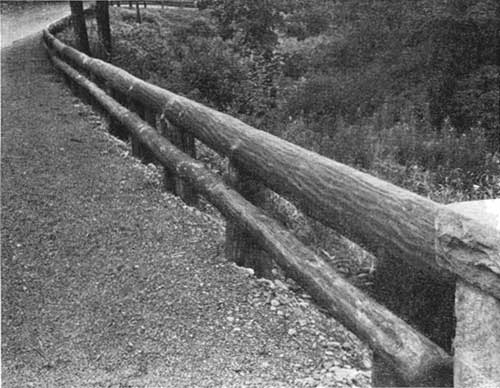

>Guardrail into Fence

Here is pictured low barrier into rail fence in slow motion. Above are departures from the simplest form—one doubling the supports, the other doubling the rail. To the left is an example having considerable height and an added buffer rail at hub cap height (a very practical provision in limitation of maintenance). Below are heavy two-rail fence with coupled posts and, finally, three-rail example with alternating wood posts and masonry piers.

|

| Plate C-2 (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| Du Page County Forest Preserve, Illinois |

|

| Cumberland Falls State Park, Kentucky |

|

| South Mountain Reservation, New Jersey |

|

| Caddo Lake State Park, Texas |

|

| Mt. Penn Park, Reading, Pennsylvania |

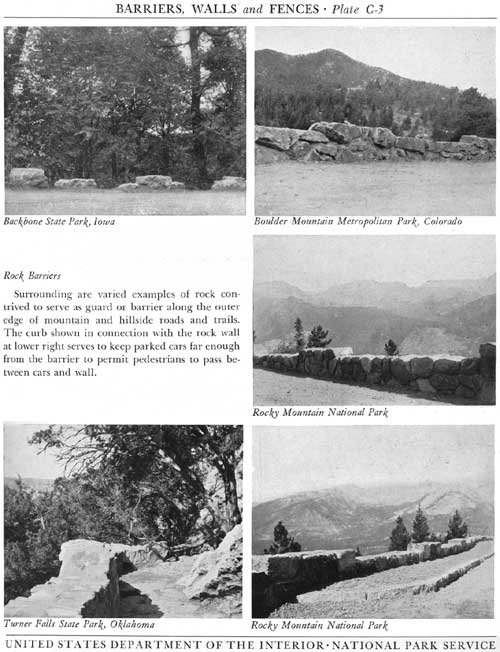

Rock Barriers

Surrounding are varied examples of rock contrived to serve as guard or barrier along the outer edge of mountain and hillside roads and trails. The curb shown in connection with the rock wall at lower right serves to keep parked cars far enough from the barrier to permit pedestrians to pass between cars and wall.

|

| Plate C-3 (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| Backbone State Park, Iowa |

|

| Boulder Mountain Metropolitan Park, Colorado |

|

| Rocky Mountain National Park |

|

| Turner Falls State Park, Oklahoma |

|

| Rocky Mountain National Park |

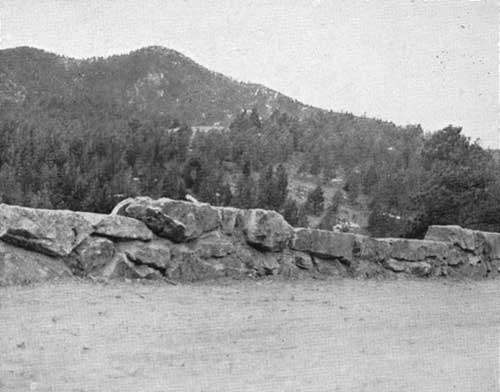

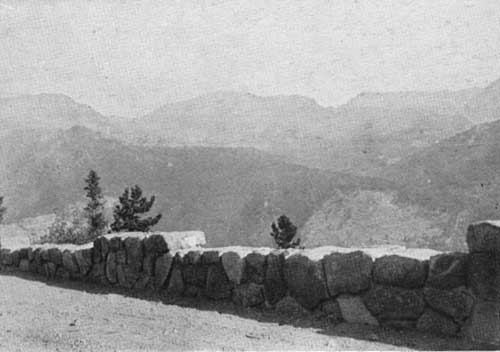

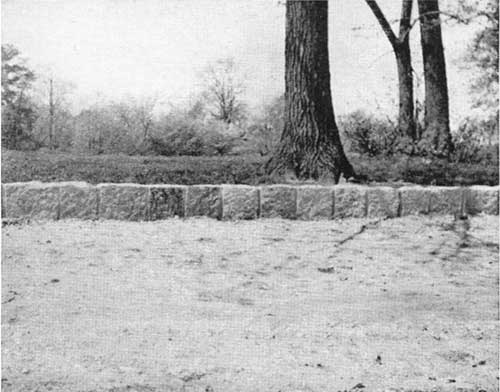

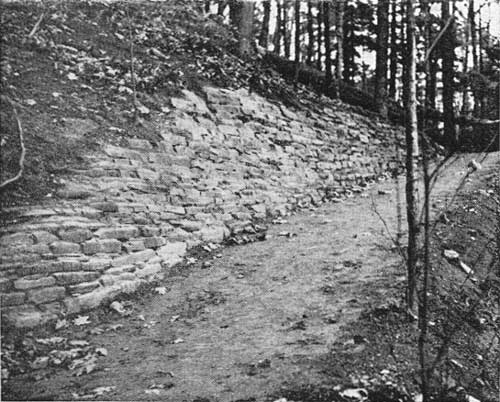

Curbs and Walls of Rock

Above are illustrated contrasting low stone curbs for the outlining of a parking area. The more formal example at upper left suggests its metropolitan location—Cook County Forest Preserve. The curb at upper right and the detail of it directly below have the informality that seems more appropriate to a wilderness setting. To the left is shown a dry-laid retaining wall of good character, and below this a splendid example of New England fence laid apparently without mortar.

|

| Plate C-4 (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| Cook County Forest Preserve, Illinois |

|

| Voorhees State Park, New Jersey |

|

| Taughannock Falls State Park, New York |

|

| Greenwich, Connecticut—Eric Gugler, Architect |

|

| Voorhees State Park, New Jersey |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

park_structures_facilities/secc.htm

Last Updated: 5-Dec-2011