|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Park Structures and Facilities |

|

OUTDOOR FIREPLACES and CAMP STOVES

THERE ARE CERTAIN FACILITIES necessary in park areas which must be based on practical considerations largely, and in which aesthetics can play but a minor part. Outdoor fireplaces for picnickers' use, outdoor stoves for campers use and various other contrivances for cooking in the open are definitely in this category.

To provide abundant hospitality for picnicking—without question the most widely used attraction offered by natural parks—requisite facilities must be scaled to peak attendances which seem to touch new highs with each succeeding summer holiday. This in terms of cooking units means uncounted numbers of them, and in our parks their multiplication has been forced at an alarming pace. Is it then any wonder that critical opinion tends to urge that fireplaces be made to attract the least possible attention, after basic practical requirements have been served?

The fundamentals are not complex. The fire-box must be properly sized and proportioned—probably a general average being 18" for width between cheek walls, 12" for height from hearth to grate, and 2'-0" for length from front to back. The dimension stated for average width is seldom varied greatly, but there are practical arguments in support of both lowering and raising of the grate. Grates set higher than 12" above the ground involve less stooping in use. When the relationship between hearth and grate is reduced to 6" or 7", there results economy of fuel. Both considerations are important, and a compromise favoring both can result when the height of the grate is kept 18" or even more off the ground, and the bed of the firebox is built up from the ground to the desired distance below the grate. But error is piled on error when the firebox is increased in size or widely varied from its tested proportions in any unwarranted experiment of building the fireplace itself beyond the tried and proved desirable maximum limits. Sufficient level shelf space on the cheek walls to either side of the firebox is useful for setting out cooking utensils and for keeping cooked food hot.

The choice of grate is affected by several considerations. The interstices should be small enough to prevent, as one of the editing committee has reasoned, "any but the most emaciated hot dog from dropping through." The Central New York State Parks Commission has developed a cast-iron grate which well meets this specification, but has also contrived, at one-tenth the cost of the cast product, a satisfactory substitute, which can be cut to size with a pair of bolt-cutters from diamond mesh culvert reinforcement. A proper evaluation of the virtue of cheapness will result from a frank recognition of the tendency to "walk away" seemingly inherent in all unanchored park accessories short of "two man" size. Chaining the grate to a staple firmly built into the fireplace wall is an alternative in long-range economy.

Movable grates are desirable, making for convenience in the removal of ashes from the firebox. Grates, subjected to the weather and intense heat, or in event of failure to keep ashes removed, deteriorate and must be replaced periodically, and the disadvantage, when these are built into the masonry, is obvious. If built into the construction, some provision for expansion under heat must be made to prevent the cracking and breaking of the masonry walls, unless these are unjoined by end wall or by foundation. If bars or rods form the grate, sleeves of pipe or tubing built into the walls to receive the grate bars permit expansion.

Fireplaces should not be placed near enough to trees to injure either branches or roots by heat. Orientation in relation to prevailing air currents is important.

Fireplaces with side walls only will take a wider variety of fuel than more enclosed structures, cool more quickly, and are less susceptible to cracking in the process. Because water thrown on all kinds of masonry when heated to high temperatures tends to cause the masonry to fracture, fires should be extinguished with earth rather than water. It is advisable to maintain a supply of earth near the fireplace for this purpose. Otherwise there may result undesirable prospecting for earth nearby.

Because some rock structures crack when exposed to great heat, it is a common practice to line fireplaces of rock with firebrick. This results in longer life for the unit, and provides a good level bearing for the grate, and is indeed practical, but detracts from the much-favored informality of the fireplace. When firebrick lining is omitted, it should be made certain in advance that the rock is a kind that will not crack or explode in heat.

The thoughtful reader will already have become aware of a hint of evasion and postponement lurking in a failure to touch upon certain details he holds highly pertinent to any discussion of outdoor fireplaces. In admitting his suspicions, it may be said that all the foregoing has been by way of honest rendering unto Practicability those things of which no gestures toward other considerations are asked. There remain to be reviewed some few fireplace practices, in appraisal of which Aesthetics and Good Sense beg to be allowed a cautionary word before Practicability speaks with loud finality.

There is first the question of chimneys as adjuncts of outdoor fireplaces. Their threatening numbers in some parks suggest a paraphrase of the figurative "inability to see the woods for the trees" to the literal "inability to see the trees for the chimneys." The pioneers, the plainsmen, who frequently cooked out of doors on the most primitive of contrivances, needed no chimney for their cooking, which on occasion embraced baking as well. It is held by many that a chimney is functionally non-essential to any fireplace, and that the open flueless fire is adequate for outdoor cooking in any situation. As our park vistas become more and more encumbered with chimneyed eruptions that assume the monumental proportions, and even the appearance, of a dismal mortuary art, the naturophile must devoutly hope that this viewpoint will be proved out to halt their further increase. It is not gross exaggeration to observe that merely topping off with cast-iron statues of military aspect the soaring piles of masonry now elbowing each other in many picnic areas, would create some very typical, and very compact, historic battlefields. This alone should bring about the general acceptance of a major precept—that no chimneyed affair will be constructed unless it shall be found that a flueless fireplace, in some draftless situation, simply will not function. Park authorities and designers should clamor for a picnic fireplace design that permits the initial building of a perfect open unit, to which a functional chimney of minimum proportions can be added, if and when found necessary. If this policy does not practically stamp out the chimney blight, then an aggressive campaign in favor of picnic menus without benefit of cooking is necessary to save many of our parks.

Conditioned upon the most restrained use of chimneyed fireplaces, principles and practices in their construction are set forth. A pronounced draft is produced only by a flue more than 5'-0" high, and some will claim 12'-0". A shorter flue will only take care of a portion of the smoke, and much will escape in the open to blacken and disfigure the chimney. The draft of the flue may be improved and the smudging of the chimney reduced by introducing a solid metal plate over or in place of the usual grill.

Chimneyed or chimneyless, the outdoor fireplace invites further discussion in the matter of materials and their manner of use. A skillful manipulation of native ledge rock or boulders in such manner as to meet all practical demands, and yet at first glance suggest a natural outcropping, is the most successful, and can take its bow on Nature's stage without blush or apology. This cannot be said for other partis, which are ever more or less ill at ease in a natural landscape. Of these others, the most satisfying in itself is the low stone unit laid up with mortar, and the closer its kinship to a natural formation or casual piling up of rock, the more pleasing it is. One blind to the fact that in some regions neither rock nor boulders are indigenous might fatuously decree that fireplaces of any other materials are still unthinkable and taboo. This view cannot be sponsored here in the face of a firm conviction that park facilities should be provided to supply all proved use-demand, and that such facilities built of materials "natural" in origin, but not "native" to the general region, are no less than arrant "nature-faking"—labored and dishonest. Fireplaces of brick or concrete are surely to be preferred to this.

Probably outdoor fireplaces of brick or of concrete are not to be seriously judged to be "landscape units." But they can be not inefficient in function, not unskilled in workmanship, not unsightly in form, within limitations of their own. They are economical in the current demand for picnic units in greater numbers, and are somehow unmannered and free of false pretense.

There are those who foresee in the expanding demand for picnic facilities the threat of fireplace units more crowded than gopher mounds on a prairie and propose to meet it by resorting to multiple fireplaces. The close coupling of units limits the sources of smoke annoyance and hazard to tree growth. There is economy of construction. The sole opposing argument, because it is based entirely on human nature, cannot be disregarded. The propelling inspiration behind most picnics is a desire to get away from crowds, to take over a small area in the open affording reasonable privacy. The massing of the cooking units brings in too close contact too many cooks, proverbially not conducive to peace and good will. Confronted with the sound reasoning both for and against multiple fireplaces, one shies at making oracular pronouncement to recommend either one to the exclusion of the other. Some of each in the picnic area may be the solution of the moment.

The discussion to this point has embraced the rather typical outdoor fireplace, and neglected the very simplest provisions for cooking out-of-doors that for some people are the most fun. A mere platform formed by a low square or circular curb of masonry, loose stone or cement, and filled level with gravel, will provide for a fire with minimum danger of its spreading. This type of open fire is satisfactory only for cooking requiring no utensils, such as toasting bread or meat, or roasting potatoes or corn in the ashes. Supplemented by two forked sticks, a cross arm and wire hooks to hold kettles, this simple facility is not necessarily inconvenient and its cooking range is widened. Again the basic hearth type may be furnished with an iron grill with legs to a considerable increase in the variety of cooking possible. In the west an iron stake driven into the ground near the center of the cleared hearth and furnished with revolving arms, adjustable for height, and fashioned to support pot, frying pan and pail, is sometimes favored.

The outdoor fireplace has been discussed herein largely as a facility for the use of picnickers in preparing one or two meals on a day's outing. On this premise, it is reasonable that subordination of the fireplace to its surroundings is to be sought even at some sacrifice of convenience in use. When, on the other hand, cooking facilities are provided within the concentration of a camping area and are intended for day-in, day-out use by camping parties over extended periods, it is equally reasonable that convenience be served at the expense of aesthetic values. Thus is the camp stove differentiated from the outdoor fireplace. Between the two extremes are many hybrids—part stove, part fireplace. The camp stove is legitimately built to greater height for added convenience and more elaborately equipped for a wider range of cooking. Since cooking on a camping expedition is not always a fair weather undertaking, a roof over the camp stove is often justified, and this necessitates a chimney.

Stove units built of cast iron and erected on masonry foundations are used in some localities. Whatever may be their superior and unique advantages for camp cooking, these seem an impropriety somehow akin to outfitting Pan with a frock coat.

In regions where the barbecue is a religion, the details of the pit are probably too much a part of the ritual itself, and too varied in strictly personal interpretations by the high priests thereof, to risk a controversy by more than mention here.

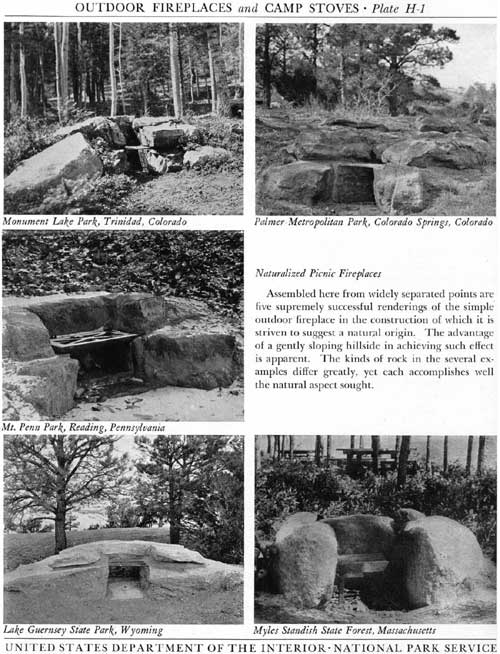

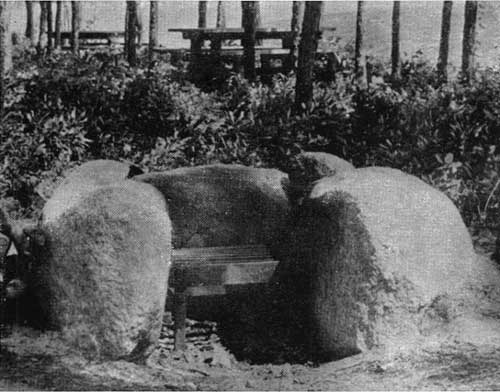

Naturalized Picnic Fireplaces

Assembled here from widely separated points are five supremely successful renderings of the simple outdoor fireplace in the construction of which it is striven to suggest a natural origin. The advantage of a gently sloping hillside in achieving such effect is apparent. The kinds of rock in the several examples differ greatly, yet each accomplishes well the natural aspect sought.

|

| Plate H-1 (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| Monument Lake Park, Trinidad, Colorado |

|

| Palmer Metropolitan Park, Colorado Springs, Colorado |

|

| Mt. Penn Park, Reading, Pennsylvania |

|

| Lake Guernsey State Park, Wyoming |

|

| Myles Standish State Forest, Massachusetts |

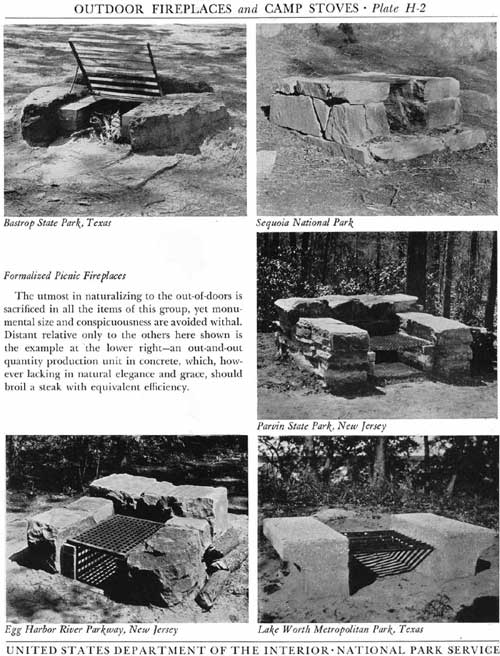

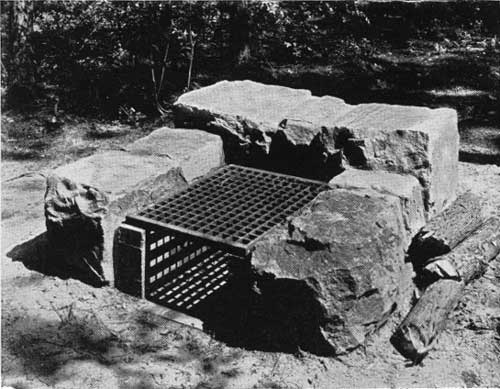

Formalized Picnic Fireplaces

The utmost in naturalizing to the out-of-doors is sacrificed in all the items of this group, yet monumental size and conspicuousness are avoided withal. Distant relative only to the others here shown is the example at the lower right—an out-and-out quantity production unit in concrete, which, however lacking in natural elegance and grace, should broil a steak with equivalent efficiency.

|

| Plate H-2 (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| Bastrop State Park, Texas |

|

| Sequoia National Park |

|

| Parvin State Park, New Jersey |

|

| Egg Harbor River Parkway, New Jersey |

|

| Lake Worth Metropolitan Park, Texas |

Miscellany of Fireplaces and Campstoves

The column to the left presents at the top picnic fireplace with modest chimney, next a typical camp stove, and at the bottom a multiple camp cooking unit. Above at the right is an open fireplace, that anticipates almost any condition of draft and is a typical facility in Minnesota Parks. At the lower right is pictured a simple campfire hearth, bounded by circular stone curb and equipped with iron stake and adjustable arms to carry cooking utensils.

|

| Plate H-3 (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| Turner Falls State Park, Oklahoma |

|

| Minnesota State Parks |

|

| Lassen Volcanic National Park |

|

| Palomar Mountain Park, California |

|

| Swan Lake State Park, Iowa |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

park_structures_facilities/sech.htm

Last Updated: 5-Dec-2011