|

Petroglyph National Monument New Mexico |

|

NPS photo | |

As you walk among the petroglyphs, you are not alone. This landscape is alive with the sights and sounds of the high desert—a hawk spirals down from the mesa top, a roadrunner dashes into fragrant sand sage, a desert millipede traces waves in the sand. Petroglyph National Monument contains over 24,000 images pecked in stone—some recognizable as animals, people, and crosses, others more mysterious. All are a part of this landscape and the spirits of the people who created them. Today these images, carved into the black rocks, invite us to step back in time, to think about the people who inhabited and traveled through the Rio Grande valley long ago. These images help us learn from those who continue to interact and reaffirm their spiritual connection with this place. Be still. You may feel another presence beyond what you can see or hear.

Each of these rocks is alive, keeper of a message left by the ancestors.... There are spirits, guardians; there is medicine....

—William F. Weahkee, Pueblo Elder

The West Mesa, a 17-mile-long table of land west of the Rio Grande, emerged about 200,000 years ago when lava flowed from a large crack in the Earth's crust. Layer upon layer of lava flowed over and around existing landforms. Eruptions continued from isolated points along the fissure, forming the cones we see today. Over time, softer sediments on the mesa's eastern edge eroded, leaving a jagged-edged escarpment strewn with basalt boulders that broke away from the lava caprock. This is the natural setting for the petroglyphs you see today.

Long ago people discovered that chipping away the rocks' thin desert varnish revealed a lighter gray beneath and left a lasting mark. American Indians believe these images are as old as time. Archeologists estimate that most of the images were made 400 to 700 years ago by the ancestors of today's Native people. Some images may be 2,000 to 3,000 years old. Beginning in the 1600s Hispanic heirs of the Atrisco Land Grant carved crosses and livestock brands into the rocks. Walking the trails and studying these petroglyphs gives you a chance to contemplate the meaning of cultural continuity in our world of fast-paced change.

Why were these images created? What do they mean? These questions may be answered by clues in the subject matter, carving technique, or setting. It took a long time to create each image with stone tools—so subject and setting for each petroglyph were carefully planned. Images of birds native to Central America indicate that the Native people were involved in an extensive cultural network. Other questions are more difficult to answer. Were nearby stone bowls, called grinding slicks, used to process plants for ritual medicines? Do spirals represent a calendar, the cycles of life, or perhaps a desert millipede? Humanlike faces look out in two directions from the corners of boulders. Are they guarding a sacred location? Only the carvers knew what messages they were conveying through the images.

Protecting the Petroglyphs

Petroglyphs are fragile, non-renewable cultural resources that, once damaged, can never be replaced. Organized efforts to protect the petroglyphs began in the 1970s with the establishment of Indian Petroglyph State Park at Boca Negra Canyon and Albuquerque's Volcano Park, incorporating the five cinder cones. In 1986 the entire 17-mile escarpment, location of most of the petroglyphs, was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Friends of the Albuquerque Petroglyphs and other groups led efforts to create Petroglyph National Monument, established by Congress in 1990.

To American Indians the entire monument is a sacred landscape. The landscape lives in the stories passed on from one generation to the next. Like other sacred places throughout the world, the area demands respect and care. We ask your assistance in protecting this rich cultural landscape. It is illegal to remove, damage, alter, or deface cultural or natural objects or sites within the national monument. Violations are punishable by costly fines and/or imprisonment. If you see any vandalism, please call Petroglyph National Monument, the Archaeological Resources Protection Act Hotline, or Open Space Dispatch.

What to See and Do

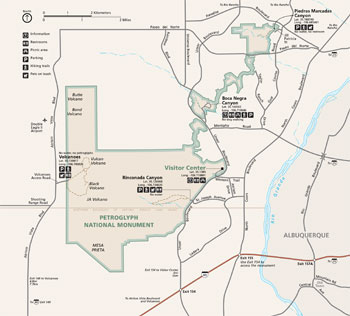

(click for larger map) |

Visitor Center Begin at the visitor center located at the intersection of Unser Blvd. NW at Western Trail NW. Take I-40 west then exit 154 (Unser Blvd.). Go north 3 miles to Western Trail, turn left, and follow signs. The visitor center is open daily 8 am to 5 pm except Thanksgiving, December 25, and January 1. Here you will find staff to answer your questions and help you plan your visit, as well as information, trail guides, restrooms, and a Western National Parks Association Store.

Trails All trails for viewing the petroglyphs are a short drive from the visitor center. Boca Negra Canyon is 2 miles north on Unser Blvd. Open daily 8 am to 5 pm (last entry at 4:30 pm). You can see petroglyphs along three partly paved self-guiding trails. Hiking times: five to 30 minutes roundtrip. Restrooms, picnic tables, and water. The City of Albuquerque manages the area. Nominal parking fee. No pets allowed. Rinconada Canyon is 1 mile south of the visitor center on Unser Blvd. A 2.2-mile roundtrip, unpaved trail follows the escarpment's base. Take water. Enter Piedras Marcadas Canyon area from a small parking lot west of Golf Course Road, off Jill Patricia Street via an unpaved 1.5-mile trail. Take water. Volcanoes day-use area offers a close-up view of area geology but does not offer petroglyph viewing. Open 9 am to 5 pm daily. Take I-40 west to Atrisco Vista Blvd. (exit 149); drive north 4.8 miles to the unmarked entrance on the right. Unpaved trail lengths vary from one to 4 miles. Take water.

For a Safe Visit Please observe these warnings: • Stay on established trails and watch for sudden storms. Take shelter in your vehicle at the first sign of thunder or lightning. Do not walk in drainages (arroyos, dry washes) or on top of the mesa. • Watch for rattlesnakes; report sightings to a ranger. • Wear sunscreen, protective footwear, and a hat. • Carry plenty of water. • Keep your pet on a leash at all times. Pick up after your animal. • There are no public phones, food service, lodging, or camping in the park; services are available nearby. • Some areas may be closed during inclement weather. • Firearms regulations are on the park website.

Accessibility We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. For information go to a visitor center, ask a ranger, call, or check our website.

Emergencies call 911

Source: NPS Brochure (2017)

|

Establishment

Petroglyph National Monument — June 27, 1990 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Acoustical Monitoring 2010: Petroglyph National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NRSS/NRTR-2013/708 (March 2013)

Acoustical Monitoring 2010 and 2012: Petroglyph National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NRSS/NRTR-2014/876 (Amanda Rapoza, Cynthia Lee and John MacDonald, November 2014)

Cultural Landscape Overview: Petroglyph National Monument, New Mexico (Peggy S. Froeschauer, September 1994)

Don Fernando Durán y Chaves's Land and Legacy (Joseph P. Sánchez, Spanish Colonial Research Center, December 1998)

Erosion assessment at the Petroglyph National Monument area, Albuquerque, New Mexico USGS Water-Resources Investigations Report 94-4205 (A.C. Gellis, 1995)

Erosion potential of the main branch of the Piedras Marcadas Watershed, Petroglyph National Monument, New Mexico (©Elaine S. Brouillard, Master's Thesis University of New Mexico, March 29, 1999)

Final General Management Plan/Development Concept Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Petroglyph National Monument, New Mexico (November 1996)

Foundation Document, Petroglyph National Monument, New Mexico (August 2017)

Foundation Document Overview, Petroglyph National Monument, New Mexico (January 2017)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Petroglyph National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2017/1547 (K. KellerLynn, November 2017)

Integrated Upland Vegetation and Soils Monitoring for Petroglyph National Monument: 2008 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS-2009/021 (James K. DeCoster and Megan C. Swan, December 2009)

Junior Ranger Activity Booklet, Petroglyph National Monument (2020; for reference purposes only)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment: Petroglyph National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/PETR/NRR-2022/2483 (Catherin A. Schwemm, November 2022)

New Area Report/Study of Alternatives: Albuquerque West Mesa Petroglyph Study Draft (June 1987)

Park Newspaper (Earth & Sky): Summer 2000 • 2010-11 • 2012-13

Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project, Petroglyph National Monument Final Report (Michael J. Evans, Richard W. Stoffle and Sandra Lee Pinel, January 14, 1993)

The Archeology of the West Mesa Area: A Summary (Matthew F. Schmader, May 1987)

The Efficacy of State Law in Protecting Native American Sacred Places: A Case Study of the Paseo Del Norte Extension (Samantha M. Ruscavage-Barz, extract from Natural Resources Journal, Vol. 47 Issue 4, Fall 2007, ©University of New Mexico School of Law)

Vegetation Classification Map: Petroglyph National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SCPN/NRTR-2012/627 (Esteban Muldavin, Yvonne Chauvin, Lisa Arnold, Teri Neville and Paul Arbetan, Paul Neville, September 2012)

petr/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025