|

National Park Service

Our Fourth Shore Great Lakes Shoreline Recreation Area Survey |

|

THE LAND AND ITS LIFE

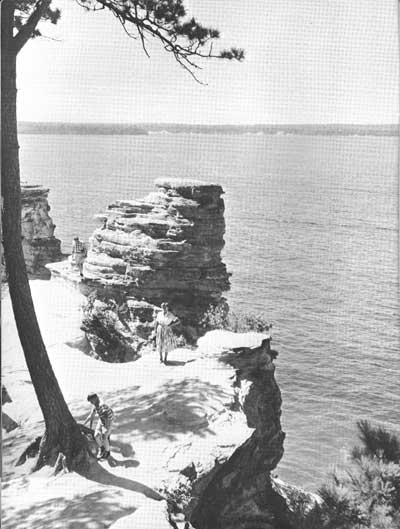

Miners Castle in the Pictured Rocks — the

architecture of wind and wave.

Geology

As in turning a gem we see flashing facets of its character, so with the Great Lakes we find endless and enchanting variety in their ever changing natural landscape. And since this is so, it seems difficult to place any one, all-inclusive stamp upon their surface to remind us that, wherever we may be along their shores, these are the Great Lakes. Yet, as surely as Mauna Loa speaks of vulcanism and the Grand Canyon of erosion, these inland seas speak of glaciation. From the "granite knobs" of the St. Lawrence to the glacier scoured vastness of Lake Superior's shores, the imprint of the Ice Age and its subsequent developments lies everywhere upon the land.

Look at the flat farmlands of Saginaw Bay and you sense the presence of a forerunner of Lake Huron, substantially larger than today, fed by the meltwater of retreating ice caps. Study the long lines of parallel ridges and troughs along Lake Michigan's north shore and you will see in graphic detail the slow lowering of the great body of water as the surface slowly sought its present level. Pick up a pebble from the morainal bluffs of rock, sand and clay deposited along the Leelanau peninsula and you may hold a segment of Canada's Laurentian Highlands, carried tediously south by the advancing glaciers.

In many ways did the ice alter the landscape. Because it was no respecter of pre-existing order, it altered previous drainage patterns. Because it was a massive carrier, it buried the entire region in an average of 40 feet of glacier drift. Because it was a tireless carver, it whittled away the trunks of ancient mountains, leaving only the hard and barren roots. Because it was an ingenious builder, it constructed vast ridges along its terminus called moraines and dotted them with lakes. Because it was a curious builder, it fashioned fields of drumlins, kames and eskers to pose riddles for the minds of men.

But it is not the footprints of glaciers alone that mark this region. Geology is as old as time, and in the ancient rocks of northeastern Minnesota is part of the dim record of the earth's beginnings. In the shales, limestones and dolomites exposed by the relentless force of the waves lie the implication of ancient salt water seas with a fossilized record of corals, molluscs, crustaceans and myriad other forms long extinct. The countless basalt flows of Lake Superior speak of fiery eruptions along that rockbound shore; events giving that coast a character all its own, dark and ominous, yet surpassingly beautiful.

The story is still being told in the battle between water and rock where the towering sandstone cliffs of the Pictured Rocks stand massively above the battering waves of Lake Superior — waves that rework the rock faces into new and changing patterns. The story still lives in the sands — ground by the glaciers, washed by the waves, and built by the winds into dunes of great extent and beauty. In this respect, the eastern and southern shores of Lake Michigan have been especially blessed.

Flora

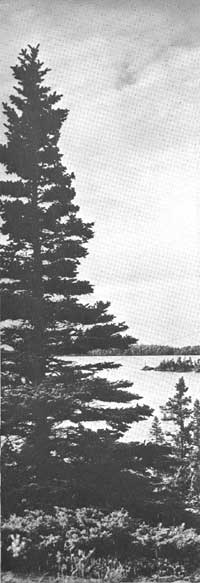

Stately evergreens stand sentinel over the rocky shores of the northern lakes. |

After the lakes lay free of the glacier's grip, the forests re-established their old hold on the land. On nature's gutted battle field, the ancient forces of erosion, deposition, soil building and growth began fashioning the new landscape. Back to the northern lakes moved the coniferous forest, scattering isolated remnants along the way. Back from the south came the hemlocks and northern hardwoods to establish their claims on the middle reaches of the lakes. Up from the south moved the species-rich deciduous trees of the central forest to take up residence on the southern shores.

The exploitation and alteration of these forests in the building of our country is a story already well known. Timber was cut for the hundred and one uses to which it is put. The pineries of the northern Lake States played out before the turn of the century. Logging, followed by incessant destructive fires, destroyed the grandeur of the old climax forests and prepared the ground for the stands of aspen, white birch and pin cherry that clothe so much of the land today. Farther south, where climate and soil permitted, the forest was cut and converted to farmland.

The picture of the forests on the Lakes today is not reassuring, but neither is it futile. Along Lake Ontario, Lake Erie and southern Lake Michigan, the forest that once lined the shores has been largely removed. This is the most prosperous agricultural area on the Lakes. It is also an industrial region and possesses the bulk of the Great Lakes human population. These people are mainly town and city dwellers with a very real need for open spaces and natural lands.

This was a region characterized by rich deciduous forests: oaks, hickories, yellow poplar, maples, and 50 or more other species that make our eastern deciduous forests so rich, stately and varied. Few other forests on earth, outside of the tropics, offer such variety and charm to the discerning eye. These are the forests of the seasons. In spring, before the dense shade of the leaves shut out the sun, the spring flowers stipple the landscape with limpid and transient beauty. Summer is the season of the green sea of light that bathes the very special environment between ground and tree top. Fall in these woods is all fire and color, for the leaf pigments of each of the many species of trees reacts differently to the arrival of frosty nights.

The deciduous forest never completely leaves the Great Lakes scene. The species diminish northward to mainly sugar maple, yellow birch and beech, or white birch, aspen and pin cherry in the disturbed areas, and though sharing the land with the conifers, they remain an integral part of the landscape.

Look on the floor of these forests and you will discover a rich flora of herbaceous flowering plants. Here, in ever appealing variety, are wood leek, cucumber root, merrybells, foam flower, trillium, wild sarsaparilla, may apple, and jack-in-the pulpit. In the few remaining segments of mature forest along Lake Ontario and Lake Erie, and particularly in the dune forests of Lake Michigan, these are especially well represented. In the unbelievably precipitous topography of the dune forests, one is apt to discover such charming plants. Cancer root, coral root, heart leaf lily; many ferns, and a host of curious and beautiful mushrooms make any hike a voyage of discovery.

Vast deciduous forests crown the

dunelands.

This is not to imply that this type of plant environment surpasses all others. The flowers of the cool, moist dune forests are not the flowers of the sandy jack pine flats, though the two may be closely adjacent. In the latter case, cow wheat, white camass, harebell, wood lily, pyrola, and partridge berry can be equally enchanting.

The delicate lady slipper — a touch of color to the somber bogs. |

No mention of the plant life of this region would be complete without mentioning the bogs. These curious little worlds-in-themselves are a characteristic feature of this glaciated landscape, particularly northward. The poorly drained, acid and sterile soil, usually with a plush carpet of sphagnum moss, sets up rigid conditions for survival and the plants that have met these conditions have largely become victims of their adjustment. Pitcher plant and sundew, both ingenious insectivorous plants, thrive in this austere environment. Bog bean, sweet gale, cranberry, leather leaf and orchids of rare beauty are fascinating examples of nature's continuous adjustment to fill every possible niche with some form of life.

People who are familiar with the Atlantic Coast beaches and dunes will recognize an old friend on the Lakes and probably guess a basic truth also. Similar environments have similar inhabitants, indeed the same inhabitants provided they can breach the intervening distances. Spring and summer, the same beach pea that makes gay the sand regions of Cape Cod, enlivens the actively moving faces of the dunes and beaches of the Great Lakes. Further investigation would disclose the presence of bearberry, and "heather grass" and, in fact, a number of other plants not commonly found through the connecting regions.

These raw and moving dunes have an entirely different group of plants than the stabilized dune forests further inland. Scattered cottonwoods, balsam poplar, isolated copses of jack pine, balsam fir, white cedar and spruce in the dune valleys, and buffalo berry and sand cherry take up the struggle with wind and sand. That they do not always win is mutely attested to by the buried hulks of old forests emerging from the windward faces of the dunes.

Fauna

Part of the charm that we associate with nature comes from contact with its wild life. A red squirrel barking defiance from a secure retreat in a fir tree animates the natural scene. A raven calling hoarsely from a lake cliff gives a voice to wilderness.

Wildlife, like plants, is controlled by its environment. The ruffed grouse dwells in the depths of the dense forests; the spotted sandpiper teeters and bobs along the lake shores. The otter makes a playground of the lakes and streams. In similar manner, every form of animal life registers distinct environmental preferences.

A very special environment is the marsh — not only for its unique assemblage of plants, but for its wildlife as well. Around the margins of the marsh prowl the raccoon, mink, otter and other predators. The muskrat is abundant enough in the marshes of the Great Lakes to make it the area's most important fur bearer. Snakes, turtles and frogs find protection and sustenance in this semi-aquatic world.

Birds, however, are the most obvious forms of marsh life. Ducks, coots, and gallinules swim and feed in the shallow waters. Rails, herons and bitterns skulk through the dense vegetation. Long-billed marsh wrens and red-winged blackbirds fill the marsh with song. Black terns, swallows and marsh hawks patrol the air, and in the edge between marsh and forest upland forms are particularly abundant.

In the wildlife management picture, marshes are vastly important as migration stopovers and nesting sites for ducks and other waterfowl. Along the shores of the Great Lakes are numerous marsh areas that could Contribute much as refuges, game management areas or public hunting grounds. Some have already been acquired for such purposes, others should be. Among these are the great wild rice marshes of the Bad and Kakagon Rivers in northern Wisconsin, the marshes of Saginaw and Green Bay, the vast stretches of western Lake Erie, and eastern Lake Ontario, including parts of the St. Lawrence River.

To save our wildlife, we must preserve their

environment. — Photograph by U. S. Fish and Wildlife

Service

Gulls — an integral part of the Great Lakes scene. |

The islands of the Great Lakes range in size from Isle Royale to small rocky out crops and transient sand and gravel bars. Because of their relative isolation and usual freedom from predators, many of the islands are used as rookeries by colony nesting birds. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service administers several of these islands, amounting to about 270 acres, as Federal Wildlife Refuges. Other important colonies, however, are not afforded this protection. Herring gulls, ring billed gulls and great blue herons constitute the bulk of these colonies, but lesser numbers of common terns, cormorants, Caspian terns, black-crowned night herons, common egrets (on Lake Erie), and bald eagles also occur.

Bird life on the Great Lakes has many engrossing aspects. Enormous flocks of waterfowl move across the area in the seasonal rhythm of migration. Shore birds of many kinds migrate across the lake or follow the north-south shores of Lakes Huron and Michigan.

Of the 300-odd species of birds found in the Great Lakes region, a number characterize the upper lakes and give a distinct Canadian or northern flavor to the area. Brightly colored warblers, known only as migrants further south, nest in the cool coniferous and deciduous forests. The loon, great gray owl, goldeneye, ring necked duck, goshawk, spruce grouse, three-toed woodpecker and gray jay testify to the Canadian character of an area like Pigeon Point, Minnesota. In winter, arctic gales occasionally drive south an assorted assemblage of far northern or arctic species including the jaegers, great black-backed gulls, murres, old squaws, scoters, eiders, hawk owls and boreal owls.

Many of these birds that live on the lakes or their tributary waters are fishers or scavengers on fish. And a varied fare they have, for around 173 species of fish inhabit this drainage system. About 30 of them are of sufficient size or abundance to enter the commercial catch; an equal number, though not necessarily of the same species, are caught by the sports angler.

The whitefish family, containing chubs, ciscos, whitefish and round whitefish, compose the most significant commercial group. The lake trout, once supplying an important fishery on Lakes Huron, Michigan and Superior, has been reduced to an unimportant position by the sea lamprey.

This eel-like, jawless parasite entered the upper lakes via the Welland Canal in the twenties and after gaining a foothold, spread like disease. Control of lamprey predation is difficult, but a possibility exists in a species-specific poison that is currently being tested which kills the young in the streams before they reach the parasitic stage and drift back to the lakes. Provided this is successful, a giant step will have been taken in restoring the lake trout fishery.

Man has long been on the Great Lakes scene, and, as everywhere where human interference operates, changes have and are taking place in the native flora and fauna. Though no well known species around the Great Lakes appear headed for outright extinction, many are in danger of being exterminated locally. The mammals provide an insight into this process, particularly the larger, widely ranging forms or those associated with specific environments.

Denizens of our northern shores. |

Only four big game species remain on the Great Lakes. Of these, only the white tailed deer is widespread and common. The black bear is found solely on the northern lakes, and the gray wolf and moose are encountered only rarely or locally on Michigan's Upper Peninsula and north eastern Minnesota. The elk, caribou, buffalo and cougar and, perhaps, the lynx have been eliminated from the Great Lakes fauna. The elk, however, has been reintroduced on the northern tip of Michigan's Lower Peninsula and seems to be thriving. Provided reserves of sufficient size could be created, other species such as the caribou and moose might be re-established.

The ranges of about 63 native mammals touch on the Great Lakes, and those not mentioned in the preceding paragraph are probably not in any immediate danger of elimination except locally. Small, shy, nocturnal or burrowing forms such as shrews, moles, bats and rodents are generally inconspicuous and can exist in close proximity to man. However, most species around the lakes are forest or woodland dwellers whose continued presence on the local scene requires that some vestige of the natural environment be left intact.

Many remaining species of Great Lakes fauna are being eliminated primarily be cause of lack of suitable habitat. Only through the establishment of protected natural areas can these species be saved. The natural areas should be held in public trust to assure their continued existence.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

our-fourth-shore/sec4.htm

Last Updated: 18-May-2016