|

REDWOOD

The Redwood State Parks |

|

EARLY LOGGING

HOW IT WAS DONE

The Russians built their colony at Fort Ross, established as a headquarters for their fur trade, almost entirely of redwood — in fact, they are supposed to have shipped a disassembled redwood house back to Russia in the most modern "pre-fab" style. And to the south, the Spanish also made some use of the tree. But, partly because of the trees' immense size that made them difficult to handle with the primitive tools available, and partly because of the colonial economy's small need for lumber, the vast redwood forest remained relatively untouched until the Gold Rush. Then American tools and skills, combined with the upsurge in demand for wood created by the influx of gold seekers, gave birth to a redwood lumbering industry almost overnight.

|

| Redwood chapel at Fort Ross State Historic Park. (Department of Parks and Recreation) |

|

| Loggers stood on springboards to reach a portion of the trunk that they could cut with a two-handed saw. (A. W. Erickson) |

|

| After the tree fell, it had to be cut into manageable sections. (A. W. Erickson) |

|

| Stream-driven winches were used to get the huge sections to a road or river. (A. W. Erickson) |

"The man who cut that tree was a damned liar!"

It took a particular breed of men to attack these enormous trees — French men, Scots, New Englanders, Scandinavians, and more came to make their mark on the forest. It sometimes took a two-man chopping team six 12-hour days to fell a redwood — and then, if the tree didn't drop just right, onto the bed of branches and underbrush prepared to receive it, it might split (due to its brittleness, the Sierra redwood trunk was particularly apt to shatter) and all the labor would be for naught.

To speed up matters, since the great swell at the base of the trees was too big for the sawmills of the day to handle anyway, loggers would notch the trunk and insert a five-foot plank — springboard — on which they could stand while chopping on a narrower portion of the trunk, sometimes as much as twenty feet from the ground.

|

| Loading timber at a "dog hole" along the Mendocino coast. (San Francisco Maritime Museum) |

|

| It might have taken the whole train to move just one tree. (Department of Parks and Recreation) |

|

| An unusual combination of steam "donkey" and barge. (Department of Parks and Recreation) |

|

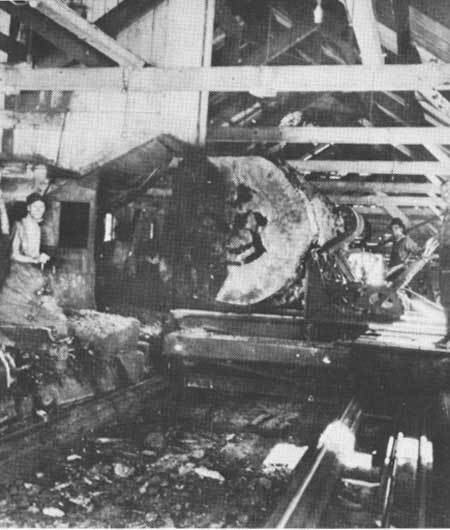

| The sawmills of the day could barely handle the huge redwood logs. (Department of Parks and Recreation) |

|

| Steep slopes made it difficult to load redwood logs aboard ship. (Department of Parks and Recreation) |

After the tree came down it was cut — or sometimes blasted — into pieces suitable for the sawmill and the bark pried off. Then the logs were rolled with jackscrews within reach of ox or horse teams to be pulled down a skid road, sometimes a "corduroy" road constructed of half-buried logs, occasionally notched to keep the loads centered. In the coastal forests the logs were often hauled to a river, where they stayed until the rainy season's high water floated them to a mill.

In the 1880s, steam revolutionized the logging industry — and made it far more destructive to the forests. The Dolbeer "donkey," a steam-driven winch that could move a log better than the strongest ox ever born, and the railroad steam engine, to move the logs to the mill, introduced "highballing," an era of high-production, careless logging. Improved metals led to the innovation of a 12- to 16-foot handsaw, with which two men could fell one or two trees a day, and mill saws too became bigger and faster.

Though local rail transport came to the northern redwoods around 1880, steam schooners put in at "dog holes" on the Mendocino coast, so called because they were "hardly big enough for a dog to turn around," until well into the twentieth century, loading the huge logs with a variety of unlikely looking equipment.

The Great Depression temporarily wiped out the demand for lumber, and permanently eliminated many marginal lumber operators. Modern equipment — the chainsaw, caterpillar tractor, lumber truck — has greatly altered logging from the "cut out and get out" days, and most of the companies that survive realize the need for better conservation practices to stay in business. According to the California Redwood Association, the coast redwood logging industry expects to be on a sustained-yield basis — cutting and re-growth rates in balance — by 1980.

The first Sierra redwood was felled in 1853 in what is now Calaveras Big Trees State Park, with the idea of putting a portion of its trunk on display. It took five men 23 days with axes, saws, and finally augers to do the job — and when it was completed, even a section of the felled trunk was too big and heavy to move. (The 24-foot stump was used as a dance floor for a time, much to the disgust of Conservationist John Muir.) Finally the bark was stripped off 21 feet of the trunk and carefully reassembled to show in San Francisco and New York.

Seeing the success of this scheme, another promoter debarked a tree without going to the trouble and expense of felling it, and put the reassembled bark on display in London. The tree, robbed of its protective covering, died a few years later; its symmetrical, fire-scarred hulk still stands at Calaveras Big Trees State Park.

Eventually whole sections of Sierra redwoods were put on display at world fairs and expositions but even so, the idea that it was all a California hoax was hard to overcome.

Serious logging in the Sierra redwoods began in the late 1880s, when a rash of suddenly filed Timber and Stone Act and "homestead" claims to redwood lands were consolidated by lumbermen. Sawmills, railroads, and flumes to get the logs to market were constructed, and about 12,000 acres were logged. Operations virtually ceased during World War I, and today the remaining 23,000 virgin acres of Sierra redwood are nearly all under the protection of the state or federal government.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

state-parks/sec3.htm

Last Updated: 14-Oct-2011