|

REDWOOD

The Redwood State Parks |

|

WHAT IS A REDWOOD

The coast redwood was first botanically classified in 1824, as a new species of Taxodium1, the bald cypress of our southeastern and Gulf states. Since those trees are primarily deciduous, the new tree was called Taxodium sempervirens (always green). Then in 1847, Austrian botanist Stephen Endlicher recognized that the tree was of an entirely new genus in the family of Taxodiaceae. He apparently decided to rename it in honor of the Cherokee Indian who had devised a special alphabet to write the Cherokee language. . .hence Sequoia sempervirens.

1Botanists classify plants according to their similarities; families of plants share certain characteristics and include genera (plural of genus) to further segregate plants that are more closely related. A genus may have one or more species, or particular kind of plant; a subspecies (variety) may have most of the characteristics of the species but differ in some slight degree such as leaf size or flower color. In a plant's scientific name, the first word refers to genus. the second to species and the third (if any) to subspecies.

|

| (John Robinson) |

When explorers of the Sierra Nevada reported discovery of an even larger red-barked tree in 1852, English botanists decided that it was of another new genus, and called it Wellingtonia gigantea after the Duke of Wellington, whose victory over Napoleon at Waterloo was then much in the public mind. American botanists, who considered it a new species of cypress and were equally patriotic, called it Taxodium washingtonianum. But in 1854, the French botanist Decaisne determined that the Sierra redwood was another species of Sequoia and called it Sequoia gigantea; this name was widely accepted (though not without some heated debate) until 1939, when more intensive studies of the two trees brought out differences greater than had previously been realized. The late Professor John T. Buchholz concluded that these differences were too great to classify both trees in the same genus, and suggested that the Sierra redwood be called Sequoiadendron giganteum (dendron is the Greek word for tree). The name was intended to disrupt the old name, Sequoia gigantea, as little as possible, while still giving it a new generic assignment. Although agreement on the new name is not universal, most botanists now seem to recognize the validity of Buchholz work.

In this booklet, Sequoia sempervirens, long termed simply "redwood," is referred to as coast redwood to distinguish it from its Sierra cousin. Sequoiadendron giganteum, sometimes called "Mammoth Tree," "Big Tree," or "Giant Sequoia," is referred to as Sierra redwood.

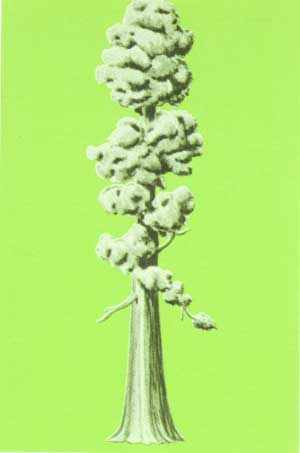

THE COAST REDWOOD

The coast redwood grows only in the summer fog belt of California's coast range, from the extreme southwestern corner of Oregon south to the Santa Lucia Mountains in Monterey County, usually at elevations no higher than 2000 feet. It grows in fairly continuous belts, rather than groves, so that you can drive for miles through redwood forest. Before California was settled coast redwood forests covered nearly two million acres, but now this has been reduced to 1,500,000 acres.

There are about 235,000 acres of virgin, or untouched, stands left, about 52,000 of which are in state parks. On the river flats of Humboldt and Del Norte Counties, the coast redwood forest achieves dense, pure stands — a "climax" forest — where, unlike the Sierra redwood, it crowds out trees of other species. This type of forest, however, occurs only under ideal conditions of soil, water, elevation, and shelter from the wind — elsewhere, according to one definition, a "coast redwood" forest may consist of up to eighty percent other trees — Douglasfir, Sitka spruce, lowland white fir, madrone, alder, tanoak, coast live oak, California laurel, willows, buckeye, big-leaf maple.

The coast redwood attains a greater average height than that of the Sierra, and may reach 350 feet or more. However, its growth rate varies widely depending on soil and weather conditions; under ideal conditions its growth is so rapid it is almost weedlike, gaining an average of two and a half feet in height every year for a century. On the other hand a fifty-year-old coast redwood in a pygmy forest might be less than twenty feet tall. The tallest currently known tree in the world is a 368-foot coast redwood growing on Redwood Creek east of Orick, in the southern part of Redwood National Park. In diameter the coast redwood comes out second to the Sierra tree; it seldom grows larger than 16 feet above the swell. Another difference is its lesser age; the coast redwood rarely reaches 2000 years.

|

| Once thought the tallest, this tree in Humboldt Redwoods State Park has been supplanted by one in the Redwood National Park. (New York Zoological Society) |

|

| This photo (left) was taken in 1910, after the hillside behind the Scotia Inn had been logged, and burned repeatedly in an effort to establish grazing land. But, as the photo at right shows, by 1965 the redwood forest had regenerated itself. (Department of Parks and Recreation) |

The root system of the coast redwood is broad and shallow. Since the most sensitive parts of the root system lie only a few inches below the surface of the ground, these trees are unusually vulnerable to anything that tends to compact the soil around them, disturbing the drainage and interrupting the flow of nutrients from the soil to the top of the tree. It is for this reason that automobile traffic may be eliminated or greatly restricted in state park redwood groves, and that campgrounds are being moved to locations outside the groves. Also, visitors are urged to walk only on the trails.

The reddish-brown, fibrous bark of the coast redwood bears a general resemblance to that of Sequoiadendron, but is somewhat darker brown and less brittle. Redwood burls, clusters of dormant buds ranging from the size of a walnut to a weight of fifty tons, are found only on the coast species.

While the Sierra redwood, because of its brittleness, has never been an important lumber species (even though it was heavily logged around the turn of the century), coast redwood lumber has long been highly valued. It is durable, rot and termite resistant, nonwarping, straight grained, relatively lightweight, able to hold nails or finishes, a good insulator, easy to work, and stronger than many softwoods and even some hardwoods. In addition to these virtues, the coast redwood is among the fastest growing of trees used commercially. On the best sites, an acre of coast redwoods can produce enough wood every decade to build three or four homes. The coast redwood lumber industry is among the most important in the state, and the species ranks high in California lumber production.

|

| Beach at Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park. (Tom Myers) |

The leaves of the coast redwood are arranged along both sides of the twigs to form flat sprays somewhat suggestive of the leaf arrangement of white fir. Coast redwood foliage from the upper branches of mature trees often resembles that of the Sierra redwood, with short, scale-like leaves densely clothing the twigs; sprays like this may be found on the ground after windy weather.

The coast redwood produces cones at an earlier age than does the Sierra redwood, and its cones mature in one year instead of two. They are a little under an inch long, and the seeds average 120,000 to the pound.

The coast redwood can reproduce by sprouting — much better, in fact, than from seed — and is one of the few coniferous trees to do so. When a coast redwood is felled or badly burned, sprouts from the stump form a circle of new trees. This tendency was a great nuisance to early settlers trying to clear the land for pasture or farming — they even occasionally resorted to cutting down the shoots "in the dark of the moon" to prevent their growing back.

Many people, because of the extreme tenacity of the tree, refer to Sequoia sempervirens as "the everliving." In addition to sprouting back vigorously when cut, mature trees may withstand devastating fires due to fire-resistant qualities of their bark and the exceptionally high water content of the cells of the wood, and can heal fire scars left on their trunks. The tree can also grow a buttress, a support to take over the function of dead or damaged roots. Should its roots be buried by flood-carried silt, it can grow a new set at a higher level.

Because the redwoods, once widespread in the Northern Hemisphere, are now restricted to such a limited range, they are often popularly looked upon as vanishing species. However, barring vast climatic changes, the phenomenal vigor of young trees both in their natural habitat and in locations to which they have been transplanted, and the remarkable ability of older trees to resist natural enemies and recover from their attacks, seem to indicate that both California redwood species are likely to thrive for many centuries to come.

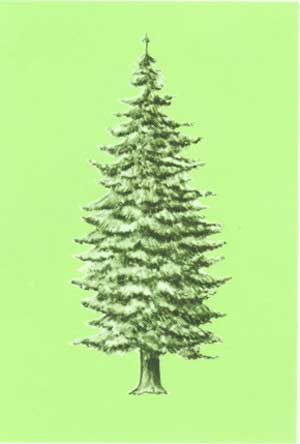

THE SIERRA REDWOOD

There are about seventy-five isolated groves of Sierra redwoods at elevations of between 4500 and 8000 feet on the west slope of the Sierra Nevada, covering a total of about 35,600 acres. Only eight of the groves are north of Kings River, so most of the trees are in Tulare and southern Fresno counties. Trees of other species — principally white fir and sugar pine, often incense cedar, ponderosa pine, and California black oak — are always found mixed with the redwoods.

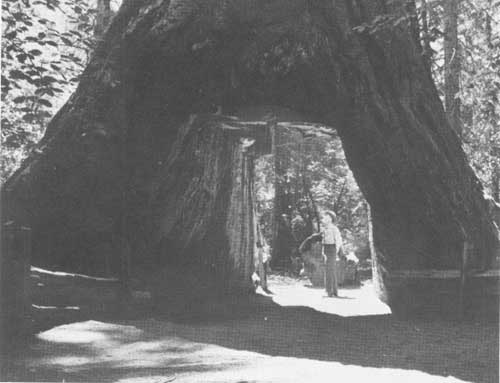

The Sierra redwood averages 250 to 275 feet in height, though taller trees are sometimes found. The tree's diameter above its great basal swell is usually 15 to 20 feet, but occasionally reaches 30 feet or more; maximum diameters at ground level are from 30 to 40 feet. At 272 feet in height and 32 feet in diameter at chest level the General Sherman Tree in Sequoia National Park, called the world's largest tree, contains 600,000 board feet of lumber — enough to build 40 houses, were it suitable for such use. At an estimated 2.5 million pounds, it may be the largest living thing.

The roots supporting this bulk do not penetrate downward much more than six feet, but laterally they reach out 200 to 300 feet, depending on the age of the tree and soil conditions. Occasionally the roots lie so close to the surface that parts of them are exposed.

|

| The tunnel through the base of this giant is big enough to drive a car through. (Department of Parks and Recreation) |

|

| This huge stump was once used as a dance floor. (Department of Parks and Recreation) |

The bark of the Sierra redwood is usually between four and eight inches thick on the upper trunk and 18 to 24 inches near the base, although a thickness of more than three feet has been encountered. On mature trees the bark is so deeply furrowed that the tree takes the appearance of an immense fluted column. The bark's soft, fibrous, almost stringy consistency would seem a flimsy protection, but it contributes greatly to making the trees almost insect and infection-proof and is nearly asbestos-like in its resistance to fire. Its rich, cinnamon-red coloring sometimes takes on a faint purplish sheen, particularly on young trees or in sheltered locations.

|

| The downed tree in the background shows the Sierra redwood's surprisingly shallow root system. (Department of Parks and Recreation) |

The wood of the Sierra redwood is a salmon pink color, turning to a rich dark maroon when exposed to the air. The wood is no longer important commercially because of its brittleness — it breaks across the grain with almost no splintering — and it is far weaker than that of the coast redwood. Although quite soft, the heartwood contains so much tannin that it is practically invulnerable to decay and insect attacks; because of its durability, fallen trees lie on the ground for centuries without showing appreciable signs of decay. This resistance to decay and insects, plus the fact that the wood contains almost no pitch and thus burns slowly, has helped many Sierra redwoods survive repeated devastating forest fires.

The leaves of the Sierra redwood are a quarter to a half inch long, attached to the stem like sharp pointed scales. The flowers are in tiny catkins, the staminate (male) and ovulate (female) borne on the same twig. In early spring the wind-scattered pollen often colors the snow a rich yellow.

The egg-shaped cones are about two inches long and take two years to mature. They are a bright green, but turn a yellow-brown color as they dry. After maturing, the cones may remain on the tree, tightly closed, with their seeds preserved inside. Between the cones' woody scales, with the seeds, is found a purple crystalline substance that is almost pure tannin. Experiments indicate that seeds soaked in a solution of this substance retain their fertility longer than untreated seeds, and thus may have a greater chance for germination and survival.

Some of the cones are cut down by Douglas squirrels for food, and their seeds released; others, a few at a time over the years, turn dry and release their seeds to be scattered by the winds. These tiny germs of life, about 200 to a cone are only a quarter of an inch long and so light that it takes ninety thousand of them to make a pound.

Even though the Sierra redwood reproduces only from seed, it would seem that the profusion of seed from the thousands of cones produced annually — since a tree may produce fertile seeds continuously from the time it is 75 years old — would result in abundant new growth. But the number of trees is fairly constant. For instance, because the forest floor is covered with a deep layer of forest litter, the seeds can't reach the soil unless it is exposed by fire, uprooted trees, or clearing — then young Sierra redwoods often sprout very thickly.

Though the Sierra redwoods were long publicized as the "world's oldest living things," they must now take second place to the much smaller bristlecone pines (Pinus aristata) found in the high ranges of the Great Basin (the White and Inyo Mountains of California, and parts of Nevada, Utah, Arizona and Colorado), some of which have reached at least 4600 years of age versus the redwoods' maximum of a "mere" 4000 years or so.

|

| This gnarled bristlecone pine may be older than the oldest redwood. (Roger and Joy Spurr, Courtesy Pacific Search) |

THE THIRD REDWOOD

For many years all the widely scattered redwood fossils in the northern hemisphere were thought to be more or less identical to the living coast redwoods, but by 1941 enough differences had been found that some of them merited a new generic name — Metasequoia. The Metasequoia, or dawn redwood, was known only as a fossil. It was considered extinct until 1944, when a Chinese professor of forestry identified specimens coming from trees growing in a remote area in central China as the "extinct" Metasequoia.

The late Dr. Ralph Chaney, University of California paleobotanist who later became president of the Save-the-Redwoods League, journeyed to China just after World War II to investigate the find and brought back specimens and seeds of this tree, which is much smaller than either of its California cousins and also differs from them in that it is deciduous rather than evergreen.

All three trees have been planted and are now flourishing in many locations throughout the world.

RANGE OF THE REWOODS

Though they cover only a fraction of their prehistoric range, the redwoods, both on the coast and in the Sierra, seem to be holding their own. Barring catastrophe, they will serve as a living relic of the distant past for centuries yet to come.

|

| (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| Coast redwoods grow almost to the ocean at Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park. (Tom Myers) |

|

| The Sierra redwood receives much of its moisture as winter snow. (Tom Myers) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

state-parks/sec6.htm

Last Updated: 14-Oct-2011