|

ROCKY MOUNTAIN

Circular of General Information 1936 |

|

ROCKY MOUNTAIN

National Park

• OPEN ALL YEAR •

ROCKY MOUNTAIN NATIONAL PARK includes within its boundaries 405 square miles, or 259,411 acres, of the Front Range of the Rockies in north-central Colorado, about 50 miles in a straight line northwest of Denver. It was established by the act of Congress approved January 26, 1915, and its boundaries adjusted by the acts of Congress approved February 14, 1917, June 9, 1926, and June 21, 1930. Its eastern gateway the beautiful valley village of Estes Park, from which easy and comfortable access is had up to the noblest heights and into the most picturesque recesses of the mountains

Rocky Mountain National Park is by far the most accessible of our national parks; that is, nearest to the large centers of population in the East and Middle West.

LAND OF LOFTY MOUNTAINS

For many years the Front Range of the Rockies has been the mecca of mountain lovers of this country. The name conjures European ideas American mountain grandeur. The selection of this particular section, with its magnificent and diversified scenic range, for national park status, met with popular approval.

It is splendidly representative. In nobility, in calm dignity, in the sheer glory of stalwart beauty, there is no mountain group to excel the company of snow-capped veterans of all the ages which stands at everlasting parade behind its grim, helmeted captain, Longs Peak.

There is probably no other scenic neighborhood of the first order which combines mountain outlines so bold with a quality of beauty so intimate and refined. Just to live in the valley in the eloquent and ever-changing presence of these carved and tinted peaks is in itself satisfaction. But to climb into their embrace, to know them in the intimacy of their bare summits and their flowered glaciated gorges, is to turn a new, unforgettable page in human experience.

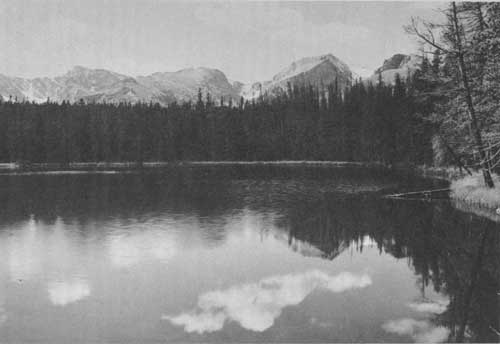

Mirror Lake fed by snow waters from eight peaks

Bierstadt Lake. Denver Tourist Bureau photo.

This national park is certainly very high up in the air. The summer visitors who live at the base of the great mountains are 8,000 feet, or more than a mile and a half, above the level of the sea; while the mountains themselves rise precipitously nearly a mile, and often even higher. Longs Peak, the largest of them all, rises 14,255 feet above sea level, and most of the other mountains in the Snowy Range, as it is sometimes called, are more than 12,000 feet high; several are nearly as high as Longs Peak.

The valleys on both sides of this range and those which penetrate into its recesses are dotted with parklike glades clothed in a profusion of glowing wild flowers and watered with cold streams from the mountain snows and glaciers. Forests of evergreens and silver-stemmed aspen separate them.

The range lies, roughly speaking, north and south. The gentler slope is on the west. On the east side the descent from the Continental Divide is precipitous in the extreme. Sheer drops of two or three thousand feet into rock-bound gorges carpeted with snow patches and wild flowers are common. Seen from the east-side valleys this range rises in daring relief, craggy in outline, snow spattered, awe inspiring.

In the northeast corner lies a spur from the Continental Divide, the Mummy Range, a tumbled majestic mountain mass which includes some of the loftiest peaks and one of the finest glaciers.

To the south of Longs Peak the country grows even wilder. The range is a succession of superb peaks. The southern park boundary unfortunately cuts arbitrarily through a superlative massing of noble snow-covered summits.

The west side, gentler in its slopes and less majestic in its mountain massings, is a region of loveliness and wildness diversified by splendid mountains, innumerable streams and lakes of great charm. Grand Lake, which has railroad connections nearby, is one of the largest natural lakes in Colorado and the deepest lake in this region. It has a growing cottage and hotel population, and is destined to become a center of much importance. The Trail Ridge Road crosses the Continental Divide and connects Estes Park on the east side with Grand Lake on the west side. The road reaches the unusual elevation of 12,183 feet above sea level.

Another road leads from the village of Estes Park up Fall River Valley to the top of Fall River Pass. This road contains 18 switchbacks and the scenery afforded is magnificent. Ascending traffic only is permitted.

EASY TO STUDY GLACIAL ACTION

One of the remarkable features of Rocky Mountain National Park is the legibility of the record left by the glaciers during the ages when America was in the making. The evidences of glacial action, in all their variety, make themselves apparent to even the most casual eye.

In fact, there is scarcely any part of the eastern side where some great moraine does not force itself upon the attention. One enormous moraine built up by an ancient glacier and rising with sloping sides nearly a thousand feet above the valley is so prominent that Moraine Park is named for it. From Longs Peak on the east side the Mills Moraine makes a bold curve which instantly draws questions from visitors.

There are several remnants of these mighty ice masses which can be seen at the present time. Three of the largest ice fields, Andrews, Rowe, and Tyndall Glaciers, are visited by many people each year, while the smaller glaciers such as Taylor and Spragues have interest and charm.

In short, this park itself is a primer of glacial geology whose lessons are so simple, so plain to the eye, that they immediately disclose the key to one of nature's scenic secrets.

LONGS PEAK

The greatest of all the mountains in the park, Longs Peak, has a massive square head. It is a real architectural structure like an enormous column of solid rock buttressed up on four sides with long rock ledges. On the east side a precipice of 1,200 feet drops sheer from the summit into the wildest lake that one can possibly imagine. It is called Chasm Lake, and there is only one month in the year when its surface is not, at least partially, frozen. Mount Meeker and Mount Lady Washington enclose it on the south and north, and snow fields edge its waters the year round.

Geologists tell us that these three mountains originally formed a single great peak. Probably then the mountain mass had a rounded summit. It was glacial action that made three mountains out of one. In the hollows just below this summit snow collected and froze. The ice clung to the granite bottom and sides, and when its weight caused it to move down the slope it plucked and pulled fragments of rock with it. The spaces thus left promptly filled with melting water, froze again, and again plucked and pulled away more rock.

Thus began glaciers which, in the ages following, carved out the great chasm east of the central peak, furrowed and molded the mountain's sides, and eventually divided its summit into the three peaks we see today. One of the smaller of these ancient glaciers, now known as Mills Glacier, though man never saw it, scooped out the chasm and piled up the Mills Moraine, which today is so picturesque a scenic feature from the valley.

In 1820 Maj. S. H. Long first saw the mountain that now bears his name. The report of his expedition records that on June 30 of that year his party caught their first glimpse of the Rocky Mountains, and particularly noted one peak, which they referred to as "the highest peak." Long's expedition followed up the valley of the Platte River, and his closest approach to the peak was at a distance of about 40 miles. Fremont found that the name Longs Peak was in general use among the fur hunters and pioneers in 1842. The first recorded ascent was in 1868, when it was climbed by W. N. Byers, Maj. J. W. Powell (who the following year made the first passage of the Grand Canyon), and five other men.

One of the striking features of Rocky Mountain National Park is the easy accessibility of these mountain tops. One may mount a horse after early breakfast in the valley, ride up Flattop to enjoy one of the great views of the world, and be back for late luncheon. The hardy foot traveler may make better time than the horse on these mountain trails. One may cross the Continental Divide from the hotels of one side to the hotels of the other between early breakfast and late dinner, or motor between these points via the Trail Ridge Road in 2 hours.

In fact, for all-around accessibility there surely is no high mountain resort of the first order that will quite compare with Rocky Mountain National Park. Three railroads to Denver skirt its sides.

This range was once a famous hunting ground for large game. Lord Dunraven, a famous English sportsman, visited it to shoot its deer, bear, and bighorn sheep, and acquired large holdings by purchase of homesteadings and squatters' claims, much of which was reduced in the contests that followed.

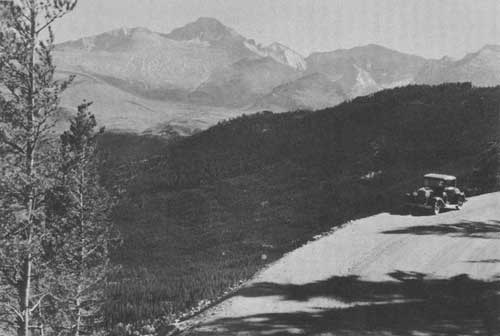

Longs Peak from Many-Parks Curve, Trail Ridge Road. Clatworthy photo.

NATURAL BEAUTIES

A distinguishing feature of Rocky Mountain National Park is its profusion of precipice-walled canyons lying between the very feet, so to speak, of the loftiest mountains. Their beauty is romantic to a high degree. Like all the other spectacles of this favored region, they are readily accessible from the valley villages by trail, either afoot or on horseback.

Usually several lakes are found, rock embedded, in such a gorge. Ice cold streams wander from lake to lake, watering wild-flower gardens of luxuriance and beauty. However, the entire park is a garden of wild flowers. From early June to late September, even into October, the gorges and the meadows, the slopes, and even the loftier summits, bloom with colors that change with the season. Blues, lilacs, and whites are the earlier prevailing tints; yellow predominates as autumn approaches.

There are few wilder and lovelier spots, for instance, than Loch Vale, 3,000 feet sheer below Taylor Peak. Adjoining it lies Glacier Gorge on the precipitous western slope of Longs Peak and holding in its embrace a group of lakelets. These, with lesser gorges cradling romantic Bear Lake, picturesque Dream Lake, beautiful Fern Lake, and exquisite Odessa Lake, and still others yet unnamed, constitute the Wild Gardens of the Rocky Mountain National Park, lying in the angle north of Longs Peak; while in the angle south lies a little known wilderness of lakes and gorges called Wild Basin.

At timberline, where the winter temperature and the fierce icy winds make it impossible for trees to grow tall, the spruces lie flat on the ground like vines; presently they give place to low birches, which, in their turn, give place to small piney growths, and finally to tough, straggling grass, hardy mosses, and tiny alpine flowers. Grass grows in sheltered spots even on the highest peaks, which is fortunate for the large curve-horned mountain sheep which seek these high, open places to escape their special enemies, the mountain lions. Even at the highest altitudes gorgeously colored wild flowers grow in glory and profusion in sheltered gorges. Large and beautiful columbines are found in the lee of protecting masses of snow banks and glaciers.

Nowhere else is the timberline struggle between the trees and the winds more grotesquely exemplified or its scene more easily accessible to visitors of average climbing ability. The first sight of luxuriant Engelmann spruces creeping close to the ground instead of rising 150 feet or more straight and true as masts arouses keenest interest. Many trees which defy the winter gales grow bent in half circles. Others, starting straight in the shelter of some large rock, bend at right angles where they emerge above. Others which have succeeded in lifting their heads in spite of winds have not succeeded in growing branches in any direction except in the lee of their trunks, and suggest big evergreen dust brushes rather than spruces and firs.

Above timberline the bare mountain masses rise from one to three thousand feet, often in sheer precipices. Covered with snow in autumn, winter and spring, and plentifully spattered with snow all summer long, the vast, bare granite masses, from which, in fact, the Rocky Mountains got their name, are beautiful beyond description. They are rosy at sunrise and sunset. During fair and sunny days they show all shades of translucent grays and mauves and blues. In some lights they are almost fairylike in their delicacy. But on stormy days they are cold and dark and for bidding, burying their heads in gloomy clouds from which sometimes they emerge covered with snow.

Often one can see a thunderstorm born on the square granite head of Longs Peak. First, out of the blue sky a slight mist seems to gather. In a few moments, while you watch, it becomes a tiny cloud. This grows with great rapidity. In five minutes, perhaps, the mountain top is hidden. Then, out of nothing, apparently, the cloud swells and sweeps over the sky. Sometimes within 15 minutes after the first tiny fleck of mist appears it is raining in the valley and possibly snowing on the mountain. In half an hour or more it has cleared.

FAUNA AND FLORA

The national park is a sanctuary for wildlife. Animals and birds are protected from hunting. Living trees may not be cut or injured. Flowers may not be picked. The cooperation of visitors is requested, in order that the wildlife of the park may be protected, that the flowers may continue in their present abundance, and that the forests of the park may not suffer injury from fire or other cause.

ANIMALS

The lofty rocks are the natural home of the celebrated Rocky Mountain sheep, or bighorn. This animal is much larger than any domestic sheep. It is powerful and wonderfully agile. When fleeing from enemies these sheep, even the lambs, make remarkable descents down seemingly impossible slopes. They do not land on their curved horns, as many persons declare, but upon their four feet held closely together. Landing on some nearby ledge, which breaks their fall, they immediately plunge downward again to another ledge, and so on till they reach good footing in the valley below. They also ascend slopes surprisingly steep.

They are more agile even than the celebrated chamois of the Swiss Alps, and are larger, more powerful, and much handsomer. A flock of a dozen or more mountain sheep making their way along the volcanic flow which constitutes Specimen Mountain in Rocky Mountain National Park is an unforgettable sight.

The beaver whose dams and other structures, both old and new, found along most streams at middle altitudes, are rarely seen except at night or very early morning. Elk occur in few places, while deer are widely distributed and at times fairly common. Coyotes and brown or black bear are occasionally seen, but these, like the mountain lion, bobcat, and small carnivorous animals are not only rare, but so wary that they are seldom seen by visitors.

Among smaller animals, the most familiar are the marmot or woodchuck, Freemont or pine squirrel, three kinds of chipmunks, and the interesting little cony or pika, which lives among the rocks on high mountains and is more often heard than seen. In all, over 60 species of mammals live in the park.

A beaver house. The entrance is under water.

W. T. Parke photo.

BIRDS

The commonest species are the western robin, the beautiful mountain bluebird, and, at middle elevations, the chickadee and junco. The hermit thrush and the solitaire, generally classed among the finest song birds in the world, are both fairly common in suitable localities; and but little inferior to these in musical performance are the purple finch, ruby-crowned kinglet, western meadowlark, and rock and canyon wrens. The graceful violet-green swallow is unsurpassed in beauty of form and color, and the crested jay, magpie, and nutcracker are conspicuous for their handsome appearance and vigorous flight. Among birds particularly interesting because of curious and unusual habits are the broadtailed hummingbird, water ouzel, campbird, nuthatch, nighthawk, and the ptarmigan, pipit, and rosy finch of the high peaks.

Although widely distributed through the park, birds are more numerous along streams and near open marshes and meadows than in the dense forests. About 100 species are found regularly in summer, and nearly 150 have been recorded during the whole year.

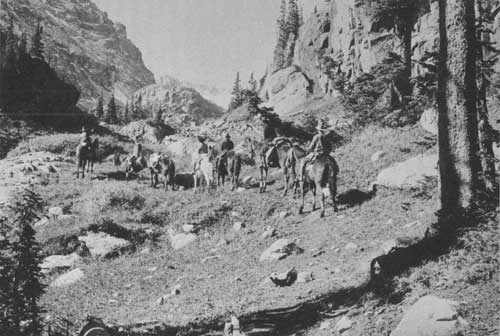

On the trail through Wild Basin. Denver Tourist Bureau photo.

FLOWERS

This park is especially notable for the presence of the blue columbine and many beautiful flowers of the gentian and primrose families; for the profusion of dwarf alpine plants on the meadows above timberline; and for the brilliance of certain species found in moist glades of the subalpine zone. Striking examples of the latter are the tall blue larkspur and monkshood, of many vivid hues, and the curious little red elephant.

Conspicuous and characteristic flowers of the lower altitudes are the mariposa lily, iris, wallflower, gaillardia, and numerous species of cinquefoil, pentstemon, and evening primrose. Among the less common groups, several delicate species of orchid, pyrola, violet, and anemone will delight the botanist. Over 700 distinct species of flowering plants have been collected within the park, and doubtless many more await discovery and identification by the careful student.

TREES

The principal trees are the Engelmann spruce, which forms extensive primeval forests in the subalpine region, the lodgepole pine, the prevailing tree of middle elevation, very common in second growth, and the ponderosa pine, a large spreading tree, occurring mainly in the lower valleys and foot hills. The limber pine is frequent in high rocky places, assuming picturesque forms at timberline, and the Douglas fir, or false hemlock, is widely distributed, while the blue spruce and alpine fir are confined to moist stream banks. In addition to the coniferous trees, there are three species of poplar, of which the commonest is the well-known quaking aspen, growing in scattered groves throughout the park.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

1936/romo/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010