|

Russell Cave National Monument Alabama |

|

NPS photo | |

It met their first need—a refuge from the elements. The cave mouth faced east, away from the cold north wind but letting in the morning sun. It would be cool in the summer. Nearby were an excellent water source, abundant wildlife, and a good supply of rock for shaping into weapon points. For the group of travelers making their way through the small valley some 9,000 years ago, the cave was perfect. People had probably already lived in the area for at least 2,000 years, but it was not until roof falls raised part of the floor above a stream that it had become permanently inhabitable.

For hundreds of generations to follow, the cave continued to draw people. Over so long a time, it is difficult to generalize about how it was used. Since the first excavation in 1953, archeologists have thought the cave was used in winter by people who in warmer months moved to villages along the Tennessee River. But the evidence is not conclusive, and it seems likely that some groups used it as a permanent home, perhaps for years at a time. Others did use it as a winter quarters, while archeological evidence does indicate that in the 1,000 years before European contact in the 1500s, people used the cave primarily as a hunting camp.

Most groups inhabiting the cave would probably have numbered no more than 15 to 30—their size limited by the need for mobility and by how many people the land could sustain. They were likely extended families or several related families. Certainly some groups would have used the cave year after year, but varying styles of spear and arrow points tell us that it was inhabited by different bands.

The artifacts they left behind tell the story of the cave: the ebb and flow of habitation, whether the users were family groups or hunting parties, what they wore, what they ate, the tools they used. As archeologists dug down to the deepest artifacts more than 30 feet below the cave's present floor, they traced the emergence of pottery more than 2,000 years ago, introduction of the bow and arrow, increasing sophistication of tools and weapons, and growing trade with other peoples for tools and ceremonial goods.

The inhabitants of Russell Cave practiced what anthropologists call "forest efficiency," using all the resources of the land. The wildlife they hunted—except for the porcupine and the peccary—are still found in the area: deer, turkey, black bear, turtle, raccoon, squirrel, and other small animals. They took fish from the Tennessee River and probably stored supplies of shellfish from the river in nearby streams. Nuts, acorns, roots, wild fruits, and seeds were staples, as were seeds from goosefoot, a small flowering plant they raised in gardens.

Although times could be hard, especially during the winter, we should not think of these people as constantly struggling, living on the margin of existence. This was a good time for people in the Southeast. Living in small family groups, they harvested rich food sources according to the season, fully exploiting their environment without destroying what sustained them.

Geology of the Cave

The rock out of which Russell Cave was carved was formed more than 300 million years ago at the bottom of the inland sea then covering the region. A layer of carbonaceous deposits (skeletons and shells) was transformed into limestone by the pressure of overlying water, sand, and mud. After the sea retreated, water dripped through fissures in the limestone. Drips became rivulets and then underground streams that cut thousands of tunnels and caverns. About 9,000 to 11,000 years ago, the collapse of a cavern roof beneath a hillside in Doran Cove created a sinkhole and exposed a tunnel carrying water deeper beneath the ground—Russell Cave. Part of the entrance was raised above water level by continuing rockfalls, and it was here that humans sought shelter as early as 7,000 BCE. It grew higher with silt deposited by flooding of the creek that still drains into the cave. The combined processes—deposits and ceiling rockfalls—caused the cave mouth to migrate up the hillside. Although the deposits eventually raised the floor above flood level, human debris and a steady rain of fine material from the roof raised it more. Today the floor of the upper entrance is some 30 feet above the original rockfall.

The Archeological Record

Russell Cave offers one of the longest and most complete archeological records in the eastern United States. The artifacts found here indicate intermittent human habitation for almost 9,000 years. Using carbon-14 dating techniques, researchers have dated to within 300 years the charcoal remains from fires uncovered at various depths. They could then date objects found at the same depth as a fire, gradually building up a continuous record. The initial excavation by the Tennessee Archeological Society in 1953 unearthed a great number of bone tools, jewelry, and pottery fragments to a depth of six feet. The Smithsonian Institution, with support from the National Geographic Society, undertook another dig from 1956 to 1958 that reached a depth of more than 32 feet. The third and final 10.5-foot excavation was done by the National Park Service in 1962 to fill out the archeological record and establish an on-site exhibit.

Do not remove or disturb any item in this park. The Archeological Resources Protection Act specifies serious felony and misdemeanor charges for removing or disturbing archeological or historical artifacts on federal lands.

Russell Cave

To characterize the evolving stages of civilization in southeastern America before European contact, archeologists have established a general cultural sequence: Paleo, Archaic, Woodland, Mississippian. While there is a general correlation between stages and the dates shown below, these characterizations are not precise for every region in a given period. Thus some peoples continued to thrive in the Woodland stage while others not far away built great cities. For most of Russell Cave's 9,000 years of human use, its inhabitants were in the Archaic stage. The cave was one of thousands of southeastern Archaic sites. Recent evidence indicates the earliest users of the cave were actually at the transitional stage between Paleo and Archaic. During the Paleo period they still depended to a great extent on hunting large animals rather than exploiting a wider range of resources.

CE 1000 to 1600

Mississippian

The Woodland period civilizations that took root in the Mississippi and Tennessee river valleys flowered in the Mississippian period. Large towns and ceremonial complexes with huge temple mounds were made possible by the refinement of corn agriculture. Because of the establishment of these permanent settlements, places like Russell Cave were used only as stopovers for hunting and trading parties. Cherokee rarely used the cave after this period.

Mississippian Period

1540 De Soto expedition explores southeastern America.

1519 Cortes begins conquest of Aztecs.

1492 Columbus reaches the Americas.

1455 Gutenberg produces first printed book in Europe.

1453 Constantinople falls to Ottoman Turks.

1300 Benin (Nigeria) empire emerges; 1325: rise of Aztecs in Mexico;

1347: Black Death (a form of bubonic plague) reaches Europe.

1000 Vikings reach North America; 1066: Normans invade England; 1096:

First Crusade.

500 BCE to 1000 CE

Woodland

In Woodland times in the Southeast, settled village life grew more important as agriculture and trade with people to the north allowed more time for refinement of political and ceremonial life. The inhabitants of Russell Cave, while retaining many of the characteristics of Archaic life, were influenced by the region's religious and political developments. Significant material changes included the introduction of pottery and the bow and arrow. Trade contacts undoubtedly accounted for much of the change, but some archeologists believe these technologies indicate the arrival of new people in the area. Domestic artifacts from the early Woodland, including the first evidence of gardening, suggest renewed use of the cave as at least a semipermanent domicile. Later in the period the cave was used mostly as a winter hunting camp when river villages dispersed into more efficient smaller groups at the onset of cold weather.

Woodland Period

900 Rise of Mississippian mound cities.

800 Charlemagne crowned first Holy Roman Emperor; 853: first printed book

in China.

600 Height of Mayan civilization; 632; beginning of Arab expansion and

spread of Islam.

160 CE Height of Roman Empire.

300 BCE Rise of Hopewell cities and chiefdoms in North America; 202:

China unites under Han dynasty; Great Wall underway.

400 BCE Founding of city of Teotihuacan in Mexico; 334: Alexander begins

march of conquest.

500 BCE China develops crossbow and iron casting process; multitiered

galleys in use; development of waterwheel; 477-429: flowering of Athenian

civilization.

700 to 500 BCE

Archaic

By about 8000 BCE, at the tail end of the last ice age, the weather had warmed enough to help cause the extinction of the large game (overhunting also contributed) on which the Paleo hunters had relied. People of the early Archaic became versatile, efficient hunter-gatherers, drawing on all the resources of forest and river. Their tools became steadily more varied and specialized. Bone and antler were shaped into an array of implements. Stone tools, long in use, were being ground and polished by the late Archaic. The mortar and pestle for milling, the fishhook, the drill, woodworking tools—all were in use. There is some evidence that for the last 3,000 years of this period, river resources became more important in the region, and Russell Cave was probably used less as a home than as a hunting camp. Changes during this period laid the foundation for area cultures that persisted until European contact.

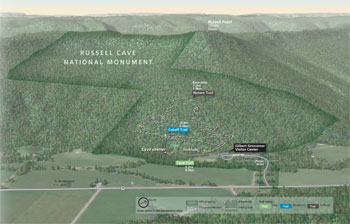

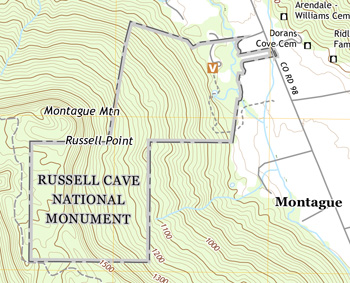

(click for larger maps) |

Archaic Period

900 BCE Foundation of Kush kingdom in Africa.

2000 BCE Advances in astronomy and mathematics; 2000-1500: Stonehenge

built 1500: Hittites perfect iron smelting; Syrians devise early alphabet; 1150:

Olmec civilization in Mexico.

3000 BCE Alloying of copper and tin to produce bronze; pottery wheel,

plow, and cart wheel; 2800: Old Kingdom founded in Egypt—first pyramids;

2500: domestication of horse in Asia.

6000 BCE Coiled pottery and weaving in Near East beginnings of

agriculture in Europe and Mexico; 5000: smelting of copper.

8000 BCE Agricultural revolution underway; domestication of animals and

cultivation of wheat and barley; bow and arrow in general use; transition to

settled villages.

10,000 BCE Hunting and gathering cultures; atlatl in general use; the

Americas settled since at least 25,000 BCE.

About Your Visit

Getting to the park Russell Cave is eight miles west of Bridgeport Alabama. From US 72 follow Route 75 north to Mount Carmel. Turn right on Route 98 and follow it to the park entrance on the left. • Open daily except Thanksgiving, December 25 and January 1.

Things to do View exhibits and cave artifacts in the visitor center. • Ask if park staff can demonstrate Archaic-period weapons and tools. • View the cave and related exhibits. • Walk the two trails. • Organized groups may arrange for guided tours.

Safety and Regulations View the cave only from the boardwalk. • Stay on trails and watch for sudden dropoffs, sinkholes, and other natural hazards. • Picnicking allowed in the picnic area, but no cooking or fires. • No camping in the park. • For firearms regulations, check the park website. • Leave all artifacts where you find them; report their location to the visitor center.

Accessibility We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. For information go to the visitor center, ask a ranger, call, or check the park website.

Source: NPS Brochure (2015)

|

Establishment Russell Cave National Monument — May 11, 1961 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

C.A.V.E.S.: A Self-Guided Education Program for Russell Cave National Monument (Emily Paris, 2013)

Cumberland Piedmont Network Ozone and Foliar Injury Report — Little River Canyon National Preserve, Mammoth Cave NP and Russell Cave NM: Annual report 2011 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/CUPN/NRDS-2013/578 (Johnathan Jernigan and Bobby C. Carson, November 2013)

Examining Erosion with a Terrestrial Laser Scanning Survey of the Russell Cave Rock Shelter, Russell Cave National Monument Final Report (Lori Collins, Travis Doering and Jorge Gonzalez, 2017)

Foundation Document, Russell Cave National Monument, Alabama (September 2014)

Foundation Document Overview, Russell Cave National Monument, Alabama (October 2014)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Russell Cave National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2014/856 (T.L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, October 2014)

Investigations in Russell Cave; Russell Cave National Monument, Alabama NPS Publications in Archeology 13 (John W. Griffin, 1974)

Junior Ranger Book (Grades 4-8), Russell Cave National Monument (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Junior Ranger Activity Book, Russell Cave National Monument (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan 2009-2018, Russell Cave National Monument (Edquist Davis Exhibits, 2009)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Russell Cave National Monument (Larry N. Beane, May 30, 1998)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment for Russell Cave National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/RUCA/NRR-2019/1942 (Jeremy Aber, Kim Sadler, Siti Nur Hidayati, Patrick Phoebus, Joshua Grinath, Racha El Kadiri, Clay Harris, Henrique Momm, Arthur Reed and Alexis Perry, June 2019)

Proclamation 3413 — Establishing Russell Cave National Monument, Alabama (May 11, 1961)

The Use of Chenopodium Seeds as a Source of Food by the Early Peoples in Russell Cave, Alabama (Carl F. Miller, extract from Southern Indian Studies, Vol. XII October 1960)

ruca/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025