|

Salt River Bay National Historical Park and Ecological Preserve Virgin Islands |

|

NPS photo | |

A Living Museum Where Nature and History Blend

Salt River Bay is a living museum on St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands. Prehistoric and colonial-era archeological sites and ruins are found in a dynamic, tropical ecosystem that supports threatened and endangered species. In 1992 Congress created Salt River Bay National Historical Park and Ecological Preserve as part of the National Park System—to preserve, protect, and tell the story of its rich contributions to the nation's natural and cultural heritage. The 1,015-acre park is jointly managed by the National Park Service and Government of the United States Virgin Islands. The area's blend of sea and land holds some of the largest remaining mangrove forests in the Virgin Islands, as well as coral reefs and a submarine canyon. Salt River Bay's natural history, its vitally important ecosystem of mangroves, estuary, coral reefs, and submarine canyon, is told below.

This setting has witnessed thousands of years of human endeavor. Every major period of human habitation in the Virgin Islands is represented: several South American Indian cultures, the 1493 encounter with Columbus, Spanish extermination of the Caribs, attempts at colonization by a succession of European nations, and enslaved West Africans and their descendants. More than a dozen major archeological investigations since 1880, together with historical research, reveal this remarkable story. Few places engage the imagination so completely, drawing visitors into the spirit of the place and its beauty and sanctity. You can help ensure that this park and its stories will always be here to inspire people about our common heritage.

Igneri, Taino, and Carib Peoples

Migratory hunter-gatherers came up the Caribbean chain of islands from South America to the Virgin Islands 4,500 years ago. By 2,000 years ago the first of three pottery-making peoples were living on St. Croix at Salt River Bay. The Igneri lived here without interruption until 700, after which the Taino gradually absorbed them. Caribs conquered and enslaved the Taino about 1425. On St. Croix, fierce Carib resistance to encroachment and enslavement led to a Spanish royal decree in 1512 ordering their extermination. Diseases new to the region contributed to the depopulation of the island by 1590.

Much of what we know about the Taino people and their culture comes from a few early European explorers who wrote eyewitness accounts, as well as from archeology. Progressive agriculturalists, they grew cotton and calorie-rich South American cassava, other food plants, and small animals. The Taino defined political leadership by chieftaincies and gave other languages words for hammock, hurricane, tobacco, barbecue, and canoe (some of their canoes could carry up to 80 people). They believed that many natural objects were keepers of primal cultural knowledge—about language, cooking, and the use of fire, for example—in a cosmos of three realms: the celestial, Earth, and subterranean lands and waters. Taino artisans expressed their world view through objects, used in daily life or for ceremonies, that they crafted of clay, stone, bone, shell, wood, or plant fiber. Today, artifacts from Salt River Bay tell the story of these Caribbean people in museums in the Virgin Islands, on the U.S. mainland, and in Europe.

Ceremonial Ball Court

On Salt River Bay's west shore an already ancient Indian settlement became a major religious and cultural center for the Taino, who lived on St. Croix from about 700 to the late 1400s. A painting depicts their village and ball court (or batey) in the 1300s. Unearthed in 1923, this is the only such ball court known in the Lesser Antilles. Both ceremonial and recreational, the ball game originated in Mesoamerica. Opposing teams tried to move a large rubber ball through the air to the other goal, using only their heads, shoulders, arms, hips—but not their feet or hands. The Taino, who traced kinship through the mother's side of the family, had ail-female teams as well as all-male teams. Petroglyphs, upright stones carved with symbols, lined the playing field. The chief, shaman, and other dignitaries sat at the head of the court, the chief and shaman on their low, four-footed, wood or stone ceremonial seats or duhos. Ornately carved and sometimes inlaid, duhos. marked power and prestige, featuring the highest Taino artistic values. Some Amazonian tribes stili use duhos today.

Like other aboriginal people of the tropics, Tainos wore little clothing. Unmarried women wore a cotton belt, while married women wore small skirts of woven cotton. Body painting was common for warfare and ceremony. The two women at the rear of the painting are squeezing grated cassava from a hanging, woven tube, to leach out the poison before making flour for bread.

An Ecological of Two Worlds

November 14, 1493: On his second voyage to the New World, Columbus sent his longboat ashore to explore the village on the west side of the bay and to search for sources of fresh water. Returning to the flagship after "liberating" some Taino slaves, his men encountered several Caribs in a canoe. They fought and each side suffered a fatality in this first documented armed resistance by natives to European encroachment in the Americas. Columbus named the site of the fight "Cape of the Arrows."

European Struggles for Control

European powers competing to dominate the New World in the mid-1600s viewed the West Indies as pivotal. They fought over St. Croix at Salt River Bay. The English (1641, 1645-50), Dutch (1642-45), French (1650-51, 1665-1733), and French chapter of the Knights of Malta (1651-65) sited their main settlement on the bay's west shore, atop part of earlier Igneri, Taino, and Carib villages. They grew cotton, indigo, tobacco, sugar, and food staples. Only one structure remains from this period: a triangular earthwork fort that the English began in 1641 and the Dutch finished in 1642. The French called it Fort Flamand (Flemish Fort) and later Fort Sale (Salt [River] Fort). It is the only such early fort left in the West Indies. Denmark ruled St. Croix from 1733 to 1917, making it a major sugar-producing island. Nearby plantations were productive until the late 1800s. The Danes built a customs post here in 1788 to thwart the bay's use for smuggling sugar, molasses, and rum to international markets.

Archeological Treasures

Salt River Bay is the most important archeological complex in the U.S. Virgin Islands. It reveals all three South American pottery-making cultures—Igneri, Taino, and Carib—and European colonists, starting in 1641. Zemis, or cemis, represented powerful spirits that inhabited Earth. A Taino cacique (chief) or behique (shaman) wore the carved conch shell mask on a cloth belt over the navel to ward off evil spirits. The fired-clay figurine is Taino or Carib (1300s to the early 1500s), possibly a chieftain in a parrot-feather headdress or a Spanish conquistador in armor.

A religious charm is a carved, hand-shaped pendant (the fingers are broken off) of ebony-like jet from northern Spain inlaid with gold leaf. It dates from between 1650 and 1665, when France and the Knights of Malta occupied Salt River Bay.

Where the Sea Meets the Land

Salt River Bay National Historical Park and Ecological Preserve is a dynamic coastal habitat whose significance extends far beyond the bounds of the bay and the park. Perhaps nowhere else in the Caribbean does a protected natural area exhibit so many of this region's important ecological relationships in so small an area. Here an upland watershed feeds into a bay fringed with mangroves and coral reefs. The mouth of the bay, with its undersea canyon and coral covered walls, opens to the sea, which falls away into the deep Virgin Islands Trough. Nutrients that well up from those deep waters feed creatures sheltered in the mangroves, including many young that will replenish fish and shellfish populations far from the bay. The water acreage of the park was also designated as a National Natural Landmark (1980) that is home to 27 species that have been listed as rare, threatened, or endangered.

In 1493 Columbus anchored his fleet here, sending soldiers ashore in search of fresh water. Salt River was a year-round stream then, but it is intermittent now because of centuries of significant land use and regional climatic change. Although Salt River Bay is St. Croix's second largest watershed, the river flows only after significant or sustained periods of rainfall.

Just offshore is the undersea canyon—as deep as 350 feet. It was carved by an ancestral river 30,000 years ago, when sea level was 300 feet lower.

The canyon runs southeast to northwest and intersects the Virgin Islands Trough, which reaches 18,000 feet in depth. Farther to the north the trough gives way to the Puerto Rico Trench, which is 28,374 feet deep—the Atlantic Ocean's deepest point.

Coral reefs occur in relatively shallow water and have built up in the Caribbean over the past 13,000 years, when the sea rose to its present level. Reefs are limited globally by water depth, temperature, and water clarity. Coral reefs are in decline in most parts of the world, so their well-being is of paramount concern not only locally but regionally and globally.

Deep Undersea Canyon

Just beyond the breaking waves Salt River Bay's submarine canyon begins, dropping to 350 feet. Its steep, nearly vertical, walls were cut in 125,000-year-old Pleistocene (Glacial) Epoch limestone, when the sea level was much lower than it is today. The walls are alive with corals, sea whips, and other marine life rivaling coral reefs elsewhere in the Caribbean. Farther offshore the sea floor falls steeply into the Virgin Islands Trough, a fault zone dividing the Caribbean and North Atlantic tectonic plates.

From Terrestrial Uplands to Estuarine Bay

Salt River Bay includes an estuary, where fresh and salt waters mix. Except for rain that falls into the bay, its fresh water comes as runoff from land around the bay. This diverse terrestrial environment, much of it not included in the park, is dominated by shrub land, nearly 40 percent of its total area. (Twenty percent of the watershed has been developed for residential use.) Much of Salt River Bay's flora is adapted to dry conditions. Evergreen shrubs, for example, bear tough, leathery leaves that have adapted to resist water loss. Woodlands and dry forest cover some 400 acres, but there is no moist forest here like that found at the northwestern end of St. Croix.

This dynamic relationship between land and bay is ecologically important. The survival of the local fishery, for example, may depend on preserving healthy natural conditions in both Salt River Bay and other protected areas. Endangered hawksbill turtles feed and sleep along the coral canyon walls. Snappers and grunts hide among coral reefs by day and feed at night in seagrass beds. Threatened green sea turtles and queen conch thrive on turtle grass, which, with manatee and shoal grasses, are the most abundant seagrass species. All these ecological niches can be affected by what takes place here, on land as well as in the water.

Mangrove Forests

Salt River Bay is fringed by mangrove forests, creating a habitat that plays a crucial role where land and sea meet. Mangroves in Triton and Sugar bays are still recovering from Hurricane Hugo (1989). Restoration is underway for red mangroves in Salt River Bay itself, which held the last major natural mangrove stand set in an estuary in the Virgin Islands.

All three mangrove species—red, white, and black—anchor themselves with a complex root system. When storms set seedlings (called "propagules") adrift, they re-anchor if they end up in shallow water. Mangrove root systems shelter hatchling sea turtles. They also serve as nurseries for vulnerable young fish, shrimp, and crustaceans that later move out to coral reefs or to sea to replenish important fisheries both locally and regionally.

By filtering water that runs off the land and into the bay, the mangrove forests protect coral reefs from sediments that can smother corals and block the sunlight they use to synthesize their food. Coral reefs serve to buffer the shoreline against the tremendous shock energy from waves driven by heavy storms and hurricanes and to replenish beaches.

Coral Reef

Nothing on land short of a carnival celebration matches the underwater world of the coral reef for dazzling brilliance. Apt description fails most snorkefers attempting to express their amazement. More than 400 species of reef fish are known in near-shore waters of these islands. No one knows the exact number of invertebrate species here, but they are integral to the coral reef community. Over millennia, millions of tiny animals called coral polyps working together have created the reef structure. Coral polyps surround themselves with exterior limestone skeletons that have been called the largest structures on Earth not built by humans. These structures form the basis for communities that are comparable with tropical rainforests for their biological richness and global significance. Coral reef diversity is the result of competition and cooperation. Corals are colonial organisms. Thousands of coral polyps that make up an individual coral structure feed by trapping tiny plankton in their tentacles. These polyps consume oxygen and organic compounds that are produced by the symbiotic zooxanthallae algae living within the coral tissues. Other, fast-growing marine algae can smother the corals—blocking lifegiving sunlight—unless the algae are grazed by reef fishes. Coral reefs may support one-third of all fish species globally and possibly a total of a half-million animal species.

Underwater Research

Salt River Bay has seen extensive undersea scientific research because it combines coral reef, water clarity, and a submarine canyon. From 1978 to 1989, successive undersea habitats here housed researchers living at a depth of 50 feet for up to 30 days. NASA used these missions to test living conditions aboard space stations. Aquanauts using the saturation diving method worked for hours underwater on studies ranging from animal behavior to geology.

Planning Your Visit

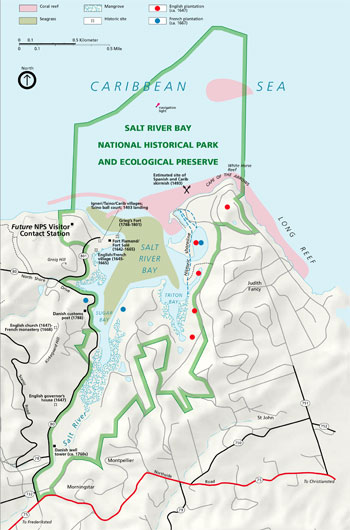

(click for larger map) |

There are currently no visitor services authorized by the National Park Service at Salt River Bay National Historical Park and Ecological Preserve. The park is in the developmental stage. Food, lodging, and other services are available in Christiansted and Frederiksted and at other island locations. There are no campsites at Salt River Bay. St. Croix has one private campground, at Mount Victory on the island's west end.

The park is five miles from Christiansted National Historic Site and can be reached by car via Rt. 75 from Christiansted, connecting to Rt. 80. Cars may be rented at the airport and various other island locations. Ask your lodging hosts for information about guided land tours. Scuba diving, snorkeling, kayaking, and hiking tours can be arranged, too.

Until there is a visitor contact station at Salt River Bay, information may be obtained at the National Park Service visitor contact station at Fort Christiansvaern, Christiansted National Historic Site. The site is open from 8 a.m. to 4:45 p.m., Monday through Friday, and from 9 a.m. to 4:45 p.m. on weekends and holidays.

All natural and cultural features of the park are protected by federal and territorial laws. Do not disturb plants, animals, ruins, or cultural artifacts. No hunting is allowed. Check on fishing and boating regulations by calling the National Park Service.

For Your Safety

Cover up, wear a hat and use sunscreen to avoid sunburn. Beware of hazardous surf conditions and crosscurrents and do not swim alone. Be cautious in shoreline shallows and in nearshore reefs; avoid potentially harmful stingrays, fire coral, spiny sea urchins, and stinging organisms. Cuts from corals and other marine life infect quickly; clean and medicate them. Corals are fragile animal skeletons; don't stand or hang on them. We recommend that you scuba dive with a professional group. Check on regulations and best practices before boating. Don't anchor in coral reef areas.

Learn to recognize and avoid hazardous vegetation. Contact with poisonous manchineel trees—including sap, leaves, bark, and fruit resembling small green apples—can cause a chemical burn. Touching your eyes after such contact can cause swelling or even temporary blindness. Contact with the holly-like Christmas bush causes a severe rash.

Please obey signs about wildlife, and keep pets physically restrained on a leash at all times to protect nesting birds and sea turtles. Travel off established roadways is not permitted. There are restrictions on campfires and the collection of firewood.

Source: NPS Brochure (2006)

|

Establishment Salt River Bay National Historical Park and Ecological Preserve — February 24, 1992 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Cooperative Multiagency Reef Fish Monitoring Protocol for the U.S. Virgin Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem, v. 1.00 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SFCN/NRR—2013/672 (David R. Bryan, Andrea J. Atkinson, Jerald S. Ault1, Marilyn E. Brandt3, James A. Bohnsack4, Michael W. Feeley, Matt E. Patterson, Ben I. Ruttenberg, Steven G. Smith and Brian D. Witcher, June 2013)

An Ecological Characterization of the Salt River Bay National Historical Park and Ecological Preserve, U.S. Virgin Islands NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS NCCOS 14 (M.S. Kendall, L.T. Takata, O.Jensen, Z. Hillis-Starr and M.E. Monaco, April 2005)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Salt River Bay National Historical Park and Ecological Preserve Cultural Landscape (December 2021)

Foundation Document, Salt River Bay National Historical Park and Ecological Reserve, U.S. Virgin Islands (February 2015)

Foundation Document Overview, Salt River Bay National Historical Park and Ecological Reserve, U.S. Virgin Islands (March 2015)

Marine Protected Areas of the US Virgin Islands Ecological Performance Report NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS NCCOS 187 (Simon J. Pittman, Laurie Bauer, Sarah D. Hile, Christopher F.G. Jeffrey, Erik Davenport and Chris Caldow, October 2014)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment: Salt River Bay National Historical Park and Ecological Preserve NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SARI/NRR-2022/2407 (Danielle E. Ogurcak, Maria C. Donoso, Alain Duran1, Rosmin S. Ennis, Tom Frankovich, Daniel Gann, Paulo Olivas, Tyler B. Smith, Ryan Stoa, Jessica Vargas, Anna Wachnika and Elizabeth Whitman, June 2022)

Salt River Bay National Historical Park & Ecological Preserve, U.S. Virgin Islands Vegetation Mapping Project, 2009 NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SFCN/NRTR-2011/448 (Jonathan G. Moser, Kevin R. T. Whelan, Robert B. Shamblin, Andrea J. Atikinson and Judd M. Patterson, April 2011)

sari/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025