|

Steamtown

Steam Over Scranton: The Locomotives of Steamtown Special History Study |

|

AMERICAN STEAM LOCOMOTIVES

In October 1942, a young Ohio railroad enthusiast named Robert Richardson, who had been drafted into the United States Army, returned from furlough at his home in Akron by way of the Southern Railway to the army's Camp Forest near Tullahoma, Tennessee. Seated next to Richardson in the coach, as it turned out, was a professor of history from the University of Kentucky at Lexington. In casual conversation, the professor learned that young Richardson had an abiding interest in railroads and railroad history.

The professor had been researching the life of a man who had died of alcoholism in a log cabin in Kentucky in 1799, he told Richardson. This man had invented a steam locomotive. Had Richardson ever heard of a John Fitch or of the locomotive he had built, a small working model, the professor inquired?

"Oh yes," said Richardson, "I've seen it."

"YOU KNOW WHERE IT IS?!?!" the professor leaped to his feet and shouted in a voice that turned heads the length of the car.

Yes, Richardson assured him, in the Ohio State Archeological and Historical Society Museum in Columbus, a stairway led down to the basement, and on a landing halfway down this stairway rested the little Fitch steam locomotive gathering dust. It had passed down through the family to the hands of a son-in-law of Fitch's who had settled in Worthington, Ohio. Somehow interested parties had learned in the 1850s that he had this historic little working model steam locomotive in his Worthington home and acquired it for the museum.

The professor became so excited he nearly left the train and reversed direction to go to Columbus to see the little engine, but eventually calmed down and continued his trip. Then he became angry because he recalled that he had written that Ohio museum, among many others, inquiring about the Fitch locomotive, and they professed to know nothing about it.

John Fitch invented the steam railroad locomotive during the 1780s and demonstrated his little working model of it before President George Washington and his cabinet in Philadelphia. His idea was to use a full-scale version of his little engine to haul wagons--freight cars, actually--across the Allegheny Mountains where the United States faced an almost insuperable problem of supplying, through a nearly roadless wilderness, Major General Arthur St. Clair's campaign against hostile British-supplied Indians of the Old Northwest.

Fitch's little locomotive operated on track made of wooden beams held in place by wheels with flanges on the outside of the wood rails, rather than inside as later became standard railroad practice. It featured a copper boiler mounted sideways on the frame and employed a sort of grasshopper lever motion to transmit power to the wheels. Fitch also invented a steam pump, a steam dredge for use in and around Philadelphia, and a steamboat that he demonstrated on the Schuykill River. He and a man named Rumsey who had invented a steamboat about the same time argued about who had been first, but both preceded Robert Fulton by many years. Fulton married into a wealthy and powerful family and managed to seize fame as the inventor of the steamboat while the much earlier Fitch and Rumsey had been forgotten.

Only a couple of feet wide and long, John Fitch's steam locomotive is the oldest such machine in the world. The steam railroad locomotive was an American, not a British, invention. But the United States of the 1790s remained primarily an agricultural society unappreciative of machinery and invention. Fitch was a man who lived ahead of his time, and his pioneering locomotive, as well as his pioneering steamboat, led to no further development of the invention. Soon both had been forgotten.

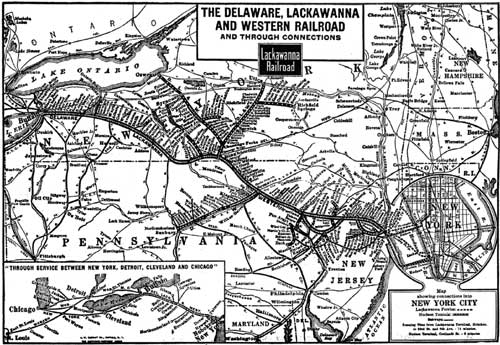

Early in the 19th century, an Englishman named Richard Trevithick also invented a steam locomotive, and within a short time the British invention led to the development of well-engineered railways. Americans, then ignorant of Fitch's pioneering inventions a quarter of a century earlier, began importing English locomotives until American foundries could meet the demand. The Delaware and Hudson Canal Company brought the first four steam locomotives into the United States from England, and it and other companies sent civil engineers abroad to study British railroad lines.

The first railroad locomotive built in the United States that actually served on a railroad was built in 1830 by the West Point Foundry Association of New York City for the South Carolina Railroad at Charleston, South Carolina. It bore the name "Best Friend." In those early years of the industry, almost any small foundry and machine shop had the capability of building a steam locomotive, and many did.

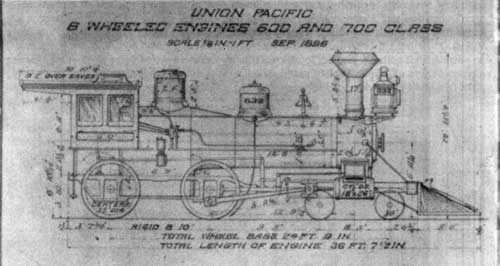

Meanwhile, English precedents did not work well in the United States. Built in well-developed and comparatively densely populated England, the English railways proved not to be well suited for American geography. Americans soon found the track over-engineered and too expensive to construct in the sparsely settled and little-developed American environs. Americans soon would devise their own cheaper systems of track construction. Starting with English prototypes, Americans also modified the locomotives with the addition of pilot trucks to help the locomotives around curves, "cowcatchers"--now known as "pilots"--cabs of different designs, headlights, and other features, so that by the 1850s American locomotives generally appeared distinctly different from English and other European locomotives. That divergence in design would continue.

From the late 1820s through the 1860s, American locomotive design progressed through a sequence of wheel arrangements, expressed by the Whyte system of classification. This system assigns a first number to a nonpowered pair of pilot wheels on a single axle, or four wheels on two axles, followed by a dash, then a figure denoting by the pair the wheels connected to a drive mechanism, followed by a dash, then a figure denoting the wheels supporting the rear end of the locomotive, again paired by the axle and generally two or four. Many locomotives lacked a trailing truck so that figure would be zero, while switch engines characteristically lacked a pilot truck, so that figure likewise would be zero in such instances.

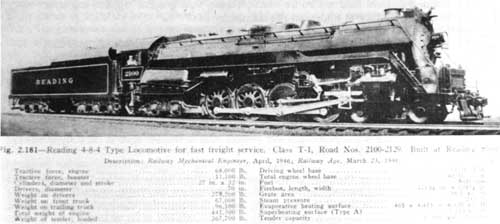

Among the earliest locomotives, the 4-2-0 wheel arrangement proved popular, only one wheel on each side of the locomotive being powered by drive rods. Soon, however, American practice developed the 4-4-0, which became so characteristically an American locomotive type during the mid-19th century that it became known as the "American" type or the "American Standard." However, as the need for more powerful locomotives developed, it was not long before locomotive designers added another axle with a pair of powered drive wheels to create the 4-6-0 and also the 2-6-0. The next step would lead to the 2-8-0. Prior to 1900, as John White pointed out, it was generally possible to increase locomotive capacity satisfactorily simply by increasing boiler and cylinder size or by raising the steam pressure the locomotive used. Thereafter, more complex developments such as superheaters, boosters, mechanical stokers, feedwater heaters, and other appliances became necessary to increase capacity while maintaining weight and other limitations. The 20th century began with the development of myriad additional wheel arrangements of locomotives. From the 4-4-0. the Atlantic type 4-4-2 developed. The "consolidation" or "consolidated" type 2-8-0 freight locomotive in time led to the Mikado type 2-8-2. The old "ten-wheeler" 4-6-0, so readily usable for freight, passenger, or mixed trains, would evolve into a larger 4-6-2. Ultimately locomotive design would embrace huge articulated locomotives as large as a 4-8-8-4 and duplex drive locomotives such as the 4-4-4-4.For the 19th century (at least to 1880), John White's seminal American Locomotives: An Engineering History, 1830-1880 provides the best overview, although Gustavus Weissenborn's American Locomotive Engineering published in 1871 also provides some excellent information. Alfred Bruce's The Steam Locomotive in America provides an excellent history of American locomotives after 1900.

The bibliography accompanying this narrative, coupled with the bibliography in White's work, guides the interested reader to the extensive literature on the subject.

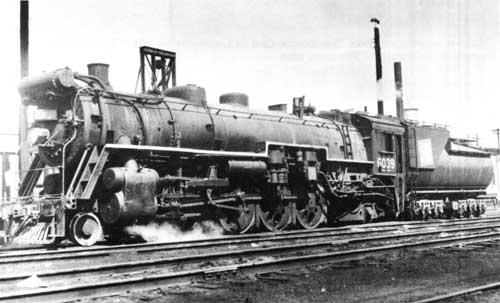

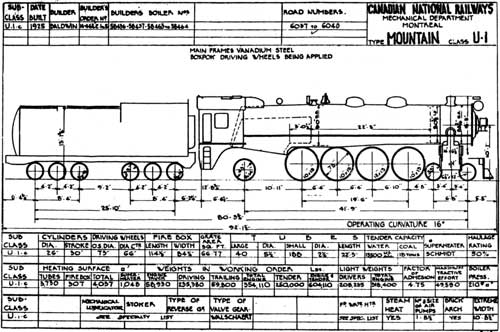

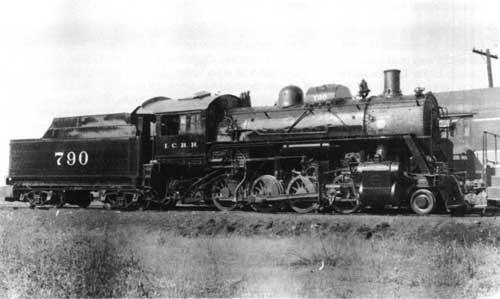

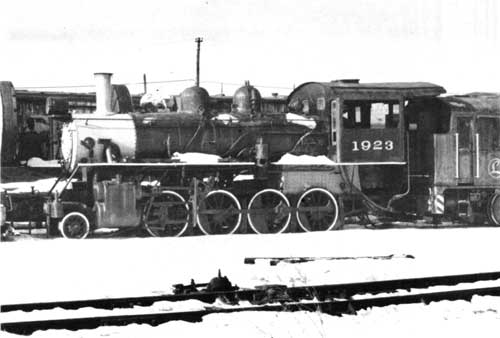

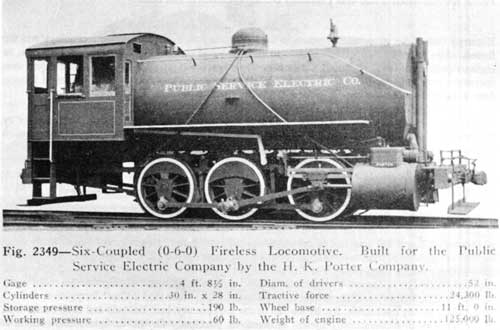

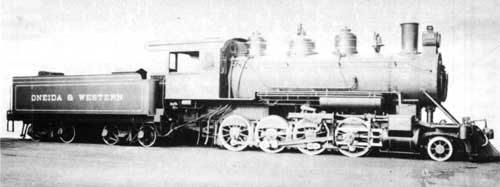

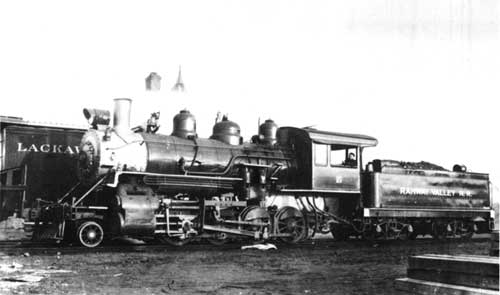

The Steamtown NHS collection includes 16 different wheel arrangements of locomotives and one geared locomotive, a Shay. The collection includes two saddle tank engines of the 0-4-OT type, one 0-6-OT, one 0-6-OF or "fireless" locomotive, one 0-6-0 with sloped tender, and one 2-4-2T. These mostly had served as industrial switchers. Of the road locomotives, the collection includes one 4-4-0, the only 19th-century engine in the collection, dating from 1887. Two 2-6-0 locomotives are in the collection, one with an all-weather cab for use along the Canadian border in upstate New York, the other one of only two Delaware, Lackawanna & Western steam locomotives to survive, and thus the only locomotive in Scranton on tracks of what had been its own railroad. The collection has one Prairie type 2-6-2, similar to the two-truck geared Shay from a logging company. Four classic 2-8-0 freight locomotives, each of a different design and different history, are in the Scranton yards. The Steamtown NHS collection of heavier duty, main line 20th-century steam motive power includes one American (and three Canadian) 4-6-2 Pacific types, one 4-8-2 Mountain type, one 2-8-4 fast Berkshire type, a 4-8-4 Northern type, and one massive 4-8-8-4 Union Pacific Big Boy. Four of the wheel types in the park's collection are represented only by Canadian locomotives; two 2-8-2 Mikado types, one 4-4-4 Jubilee type, one 4-6-4 Hudson type, and one 4-6-4T Baltic Tank.

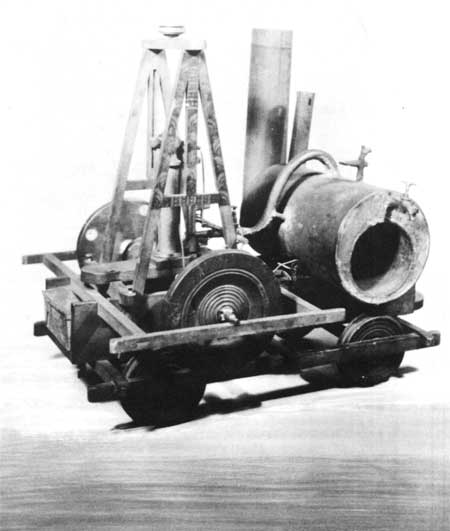

The American inventor John Fitch of Philadelphia made this model of a steam locomotive probably during the 1780s or 1790s. It now rests in the Ohio Historical Society Museum. Collection of Robert W. Ricardson |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexander, Edwin P. Iron Horses: American Locomotives, 1829-1900. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1941.

__________. American Locomotives: A Pictorial Review o Steam Power, 1900-1950. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1950.

Bruce, Alfred W. The Steam Locomotive in America: Its Development in the Twentieth Century. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., Inc., 1952.

Bryant, H. Stafford, Jr. The Georgian Locomotive; Some Elegant Steam Locomotive Power in the South and Southwest, 1918-1945: An Episode in American Taste. New York: Weathervane Books, 1962.

Collias, Joe G. The Last of Steam. Berkeley: Howell-North Books, 1960. Includes material on Union Pacific Big Boys, pp. 177-187.

Comstock, Henry B. The Iron Horse; America's Steam Locomotives: A Pictorial History. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1971.

Conrad, J. David. The Steam Locomotive Directory of North America. 2 vols. Polo: Transportation Trails, 1988.

Farrell, Jack W. North American Steam Locomotives: The Berkshire and Texas Types. Edmonds: Pacific Fast Mail, 1968.

Farrell, Jack W., and Mike Pearsall. North American Steam Locomotives: The Northerns. Edmonds: Pacific Fast Mail, 1975.

Hauff, Steve, and Jim Gertz. The Williamette Locomotive. Portland: Binford & Mort, 1977. The Heisler Locomotive. Lancaster: Benjamin F.O. Kline, Jr., 1982.Hirsimaki, Eric. Lima, The History. Edmonds: Hundman Publishing, Inc., 1986. 351 pp. [Contains rosters of all Lima Shay & Rod engines]

Howard, F.H. "Pilots . . . The Symbolism of the Art." Trains, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Jan. 1956): 38.

Johnson, Ralph. The Steam Locomotive: Its Theory, Operation, and Economics Including Comparisons with Diesel-Electric Locomotives. New York: Simmons-Boardman Publishing Corp., 1942.

King, E.W. "Concerning Stephenson, Walschaert, Baker, Southern, and Young." Trains, Vol 44, No. 7 (May 1984): 34-41.

Koch, Michael. The Shay Locomotive: Titan of the Timber. Denver: World Press, 1971.

LeMassena, Robert A. Articulated Steam Locomotives in North America, Vol. 1. Silverton: Sundance Books, 1979. [No Vol. 2 has yet been published.]

__________. American Steam, Vol. l. Denver: Sundance Publications, Ltd., 1987, 256 pp.

List of Steam Locomotives in the United States. Denver: Centennial Rail, Ltd., 1986.

Locomotive Dictionary. 1909 edition. New York: The Railroad Age Gazette, 1909.

_________. 3rd ed. New York: Simmons-Boardman Publishing Co., 1912.

Locomotive Dictionary and Cyclopedia. 5th ed. New York: Simmons-Boardman Publishing Co., 1919.

Locomotive Cyclopedia of American Practice. 7th ed. New York: Simmons-Boardman Publishing Co., 1925.

_________. 9th ed. New York: Simmons-Boardman Publishing Co., 1930.

________. 10th ed. New York: Simmons-Boardman Publishing Co., 1938.

_________. 11th ed. New York: Simmons-Boardman Publishing Corn., 1941.

_________. 13th ed. New York: Simmons-Boardman Publishing Corn., 1947.

_________. 14th ed. New York: Simmons-Boardman Publishing Corp., 1952.

Lucas, Walter A. 100 Years of Steam Locomotives. New York: Simmons-Boardman Publishing Corp., 1957.

_________. Locomotives and Cars Since 1900. New York: Simmons-Boardman Publishing Corp., 1959.

Olmsted, Robert P. A Long Look at Steam. n.p.: Published by the author, 1965.

__________. Locomotives, Limited and Locals. n.p.: Published by the author, 1977, 136 pp.

Pennoyer, A. Sheldon. Locomotives in Our Lives. New York: Hastings House, 1954. [Chapter XII, pp. 99-102, deals with preserving D.L. & W. Camel No. 952.]

Plowden, David. Farewell to Steam. Brattleboro, Vt.: The Stephen Green Press, 1966. [See pp. 114-151. The rest of the book deals with steamships.]

Ranger, Dan, Jr. Pacific Coast Shay: Strong Man of the Woods. San Marino: Golden West Books, 1964.

Ranger, Ralph D., Jr. "Shay: The Folly That Was Worth a Fortune." Trains, Vol. 27, No. 10 (Aug. 1967): 32-49.

Reisdoff, North American Hudsons: The 4-6-4 Steam Locomotive. Henderson: Service Press, 1987.

Sinclair, Angus. Development of the Locomotive Engine. New York: Angus Sinclair, 1907.

Swengel, F.M. The American Steam Locomotive, Vol. 1. The Evolution of the Steam Locomotive. Davenport: Midwest Rail Publications, 1967.

Taber, Thomas, III, and Walter Casler. Climax: An Unusual Steam Locomotive. Rahway: Railroadians of America, 1960.

White, John H. American Locomotives: An Engineering History, 1830-1850. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1968.

__________. A Short History of American Locomotive Builders in the Steam Era. Washington: Bass, Inc., 1982.

Wiener, Lionel. Articulated Locomotives. New York: Richard R. Smith, 1930.

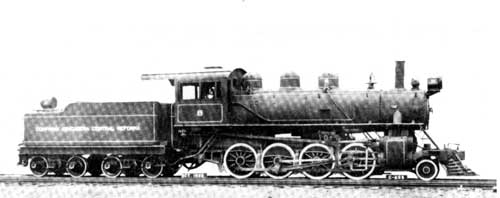

BALDWIN LOCOMOTIVE WORKS NO. 26

Owner(s):

Baldwin Locomotive Works (Eddystone) 26

Jackson Iron & Steel Company 3

Whyte System Type: 0-6-0 Switch engine

Class:

Builder: Baldwin Locomotive Works

Date Built: March 1929

Builder's Number: 60733

Cylinders (diameter x stroke in inches): 20 x 24

Boiler Pressure (in lbs. per square inch): 180

Diameter of Drive Wheels (in inches): 50

Tractive Effort (in lbs.): 29,375

Tender Capacity:

Coal (in tons):

Oil (in gallons):

Water (in gallons):

Weight on Drivers (in lbs.): 124,000

Remarks: This is a typical switch engine or switcher with a sloped back tender.

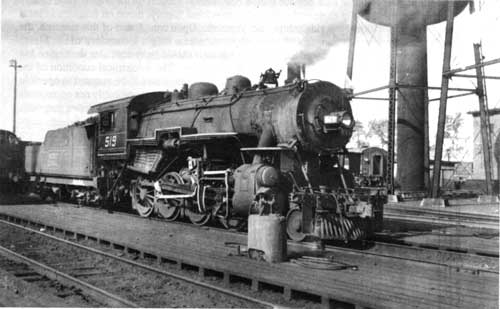

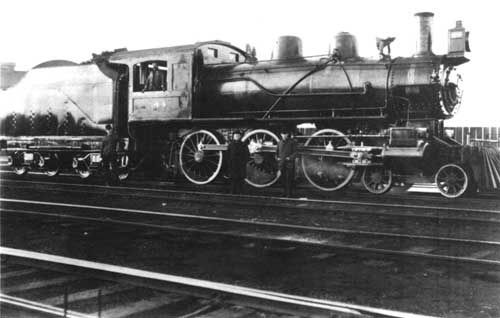

Baldwin Locomotive Works, 0-6-0 Switcher No. 26

History: The only typical switch engine in the Steamtown collection, equipped with the only sloped tender in the collection, Jackson Iron and Steel Company 0-6-0 No. 3 rolled out of the Baldwin Locomotive Works in March 1929, but instead of selling it to some railroad or industry, the Baldwin company retained the locomotive for switching duties at the massive Eddystone Plant. Baldwin had built many locomotives at the Eddystone plant since 1910, but it was not until October 1929 that the company moved all locomotive production there from its cramped Philadelphia shops. One may surmise that the little 0-6-0 was retained by the company for work in enlarging the Eddystone plant for its absorption 7 months later of all of Baldwin's locomotive production.

Ironically October 1929, the month of Eddystone's ascendency, also featured the stock market crash of Black Friday. With the onset of the Great Depression, Eddystone's locomotive-building business nearly vanished overnight.

In 1939, Baldwin offered its first standard line of diesel locomotives, all designed for yard service. Two years later, American entry into World War II destroyed Baldwin's diesel development program when the War Production Board dictated that Alco and Baldwin produce only limited numbers of diesel yard switch engines while the Electro-Motive Division of General Motors Corporation won the assignment to produce road freight diesels, which gave the latter an advantage over its competitors in that line in the years that followed World War II.

Business declined drastically in the postwar years as Alco (American Locomotive Company) and E.M.D. seized the bulk of the diesel market from Baldwin, Lima-Hamilton Corporation, and Fairbanks- Morse. Baldwin also misjudged the market, concentrating on products of little interest to railroads. In July 1948, Westinghouse Electric, which had teamed with Baldwin to build diesel and electric carbodies, purchased 500,000 shares, or 21 percent, of Baldwin stock, becoming the largest shareholder. Baldwin used the money to cover various debts. Westinghouse Vice President Marvin W. Smith became Baldwin's president.

Whether this corporate shuffle had anything to do with it, or whether Baldwin, moving to develop an improved line of diesel locomotives, wanted to project a more modern image, in 1948 the company sold one of its own switch engines, No. 26, to the Jackson Iron and Steel Company of Jackson, Ohio, where the locomotive became the steel company's No. 26.

Jackson Iron and Steel Company was a fairly old firm. In 1906, Moses Morgan, John F. Morgan, David D. Davis, John J. Thomas, and Henry H. Hossman combined their resources to finance construction of a new pig iron furnace in Jackson, Ohio. First they purchased the mine and equipment of the Jackson and Muncie Coal Company and then, on August 6, 1906, incorporated the Jackson Iron and Steel Company.

Baldwin Locomotive Works switch engine

No. 26 exhibited its original paint and lettering at the Eddystone Works

in Pennsylvania where the company retained the locomotive as its own

shop switcher.

Collection of Thomas Lawson, Jr.

Two miles west of Jackson on the banks of a small creek known as Givens Run, near the coal mine, which was known for its production of fine Sharon No. 1 coal, the new company commenced construction of its new furnace. Construction proceeded throughout 1907, but slowed with the impact of the sharp little depression that hit mines and industries especially hard that year, and the furnace was not blown in until October 6, 1908. It was the twenty-third, and probably the last, pig iron furnace to be built in Jackson County. The stack was hand filled and auxiliary equipment included three boilers, three hot blast stoves, and one blowing engine. Furnace capacity was 40 tons per day, all of which was cast in sand beds. The product was known as "JISCO [from the initials of the company] Silvery Pig Iron."

As the years passed the company made many improvements. In 1914 the firm adopted a stock bin system, larry car, and skip hoist and built two more boilers and one more stove. In 1917, with America entering World War I, the firm added a fifth stove and a sixth boiler, but still cast the pig iron in a sand bed. More extensive remodeling took place in 1923, and a larger expansion, in 1928, was just in time for the Depression. However, even in the depths of the Depression the furnace received one more remodeling, with three Cottrell Precipitators being added to clean the furnace gas.

World War II followed, along with yet another remodeling in 1942, which included dismantling the old stack and construction of a new one. The company at that time made many other improvements, including construction of a sixth hot blast stove, remodeling of the engine house, extension of the ore trestle, purchase of two new diesel-electric cranes, installation of Carrier air conditioning to dehumidify the hot blast, construction of another battery of boilers, and purchase of a diesel-electric switch engine.

It remains a mystery why, having used a diesel-electric switcher, in 1948 the Jackson Iron and Steel Company purchased secondhand from Baldwin a recently overhauled coal-burning 0-6-0 steam switch engine with a slope-backed tender. Possibly it was a matter of fuel economy, since the Jackson company owned a coal mine but not oil wells and refinery. Whatever the reasons, the company acquired Locomotive No. 26, which had switched Baldwin's Eddystone plant. Some time between 1945 and its sale in 1948, Baldwin had apparently given the locomotive a thorough overhaul. Eventually, Jackson Iron and Steel Company renumbered the locomotive 3.

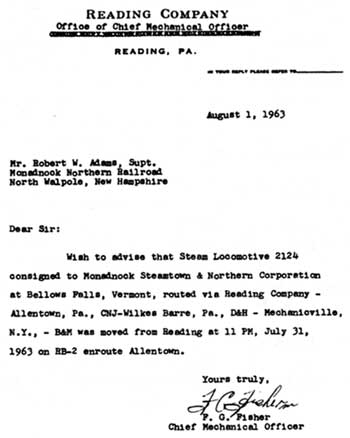

While the history of the use of the switcher by Jackson Iron and Steel Company is unknown, presumably it switched empty cars into the plant and loaded cars out to the two railroads that served the plant, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and the Detroit, Toledo and Ironton Railroad. When it last operated for the steel company is unknown, but it apparently remained there for nearly 31 years. In 1979, Jerry Jacobson purchased the locomotive. It remained in Jackson until June 1983, when it moved to Grand Rapids, Ohio, then in July 1983 to the Mad River and N.K.P. Railroad Museum at Bellevue, Ohio. It remained there until January 1986, when that museum traded the locomotive to the Steamtown Foundation for Canadian National Railways 4-6-0 Locomotive No. 1551. However, the locomotive remained in Ohio while the Steamtown Foundation transferred its collection to the National Park Service and went out of business, and it was not until January 1990 that the locomotive arrived in Scranton.

A total of about 112 0-6-0 type switch engines with tenders survive in the United States. Typically, they have a brakemen's footboard across the front of the locomotive instead of a pilot, and a similar footboard across the rear of the tender. Generally they featured one of three types of tenders: a standard rectangular tender, a slope-backed tender, or a Vanderbilt tender with its cylindrical tank. The 0-6-0 was probably the most typical of all switch engines; the next most typical was the larger 0-8-0 type. Usually, such locomotives switched freight and passenger cars at major terminals and yards.

Condition: While stored in Bellevue, Ohio, and up to the time it moved to Scranton, this locomotive reportedly was serviceable. In January 1990. it entered the shop at Steamtown National Historic Site for minor work preparatory to assigning it to hauling yard tours during the summer season of 1990.

Recommendation: As the only typical switch engine in the Steamtown collection, the locomotive is recommended for restoration to operable condition. As the Steamtown collection has other locomotives that represent trackside industrial concerns such as a steel works, it is desirable to restore this particular locomotive to represent its role as a switch engine at Baldwin's Eddystone Plant, an association that will lead into interpretation of the locomotive-building industry and especially the history of the Baldwin firm, probably for much of its history the most prominent of all American locomotive-building firms.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ahrens, Chris, Chief Mechanical Officer, Steamtown National Historic Site. Telephone communication with author, Mar. 26, 1990.

The Baldwin Locomotive Works, Philadelphia--The Story of Eddystone. Philadelphia: Baldwin Locomotive Works, 1928.

Conrad, J. David. The Steam Locomotive Directory of North America, Vol. 1. Polo: Transportation Trails, 1988: 107.

Directory, Iron and Steel Plants. Pittsburgh: The Andreson Company, 1925. [See entry for Jackson Iron and Steel Co.]

Directory, Iron and Steel Plants. Pittsburgh: Steel Publications, Inc., 1935: 50.

Directory, Iron and Steel Plants. Pittsburgh: Steel Publications, Inc., 1948: 59.

Dolzall, Gary W., and Stephen F. Dolzall. Diesels from Eddystone: The Story of Baldwin Diesel Locomotives. Milwaukee: Kalmbach Books, 1984.

The Story of Eddystone: A Pictorial Account of the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1928. Felton: Glenwood Publishers, 1974. [This is a reprint, with added material, of a 1928 publication by the Baldwin Locomotive Works.]

A Story of SPEED in Blast Furnace Construction. Jackson, Ohio: Jackson Iron and Steel Company, 1942: 3.

Westing, Fred. The Locomotives that Baldwin Built. Seattle: Superior Publishing Company, 1966.

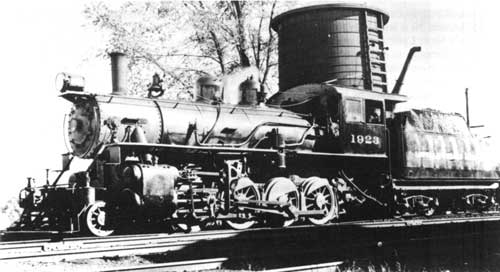

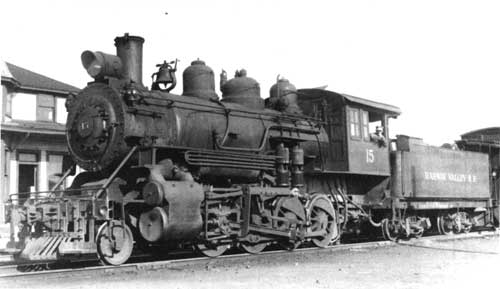

BERLIN MILLS RAILWAY NO. 7

Owner(s):

Berlin Mills Railway 7

Groveton Papers Company 7

Woodsville, Blackmount & Haverhill Railroad 7

Whyte System Type: 2-4-2T "Saddle tank"

Class: (Builder's) I-15-S

Builder: Vulcan Iron Works, Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania

Builder's Number: 1679

Date Built: January 1911

Cylinders (diameter x stroke in inches): 17 x 24

Boiler Pressure (in lbs. per square inch): 140

Diameter of Drive Wheels (in inches): 44 (possibly reduced to 38)

Tractive Effort (in lbs.): 21,720

Tender Capacity:

Coal (in tons): 2

Oil (in gallons): not applicable

Water (in gallons): 1,500

Weight on Drivers (in lbs.): 85,000

Remarks: Engine is a hand-fired coal burner in near-operable condition.

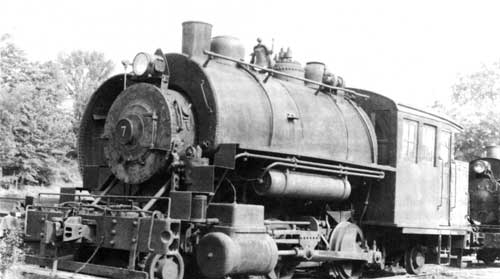

Berlin Mills Railway 2-4-2T Locomotive No. 7

History: Railroads played an important role in opening up to industry and development not only the Western frontier but also the more remote areas of long-established states. Berlin Falls, New Hampshire, is an example. Thomas Green had attempted to use this obvious source of water power on the Androscoggin River as early as 1826, but without success because his location was too far from market in an era of animal-powered transportation. Such development had to wait until groups of businessmen in Montreal, Canada, and Portland, Maine, organized to bring the new form of transportation to Berlin Falls.

After many trials and tribulations, Maine governor Hugh Anderson signed a charter of the Atlantic & St. Lawrence Railroad on February 10, 1845. Cooperating Montreal businessmen obtained a charter for the St. Lawrence & Atlantic Railroad on March 17, 1845. Together, the two companies proposed to construct a railroad between Montreal and Portland across the province of Quebec and the states of Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. Of course, the companies now had to sell stock, send out surveyors and civil engineers, select routes, hire construction forces, arrange to have cross-ties cut, order and purchase rail, locomotives and cars, and perform all the other myriad tasks necessary to turn a railroad from a creation on paper to a functioning system of wood and iron, steel and steam.

Directors of the Atlantic & St. Lawrence Railroad broke ground in Portland on July 4, 1846. It took until July 22, 1851, for construction to allow the first train to enter Gorhan, New Hampshire--over 91 miles of track. Construction resumed and reached Northumberland (today's Groveton) on July 12, 1852, passing through Berlin Station en route. Meanwhile, the St. Lawrence & Atlantic built southeastward from Montreal, and the two companies had agreed on August 4, 1851, to join at the town of Island Pond, Vermont. The first regularly scheduled through train between Montreal and Portland operated on April 4, 1853. Meanwhile, the directors had negotiated the joining of the two railroads between Portland and Montreal into the Grand Trunk Railway Company of Canada, which they accomplished through a 999-year lease dated August 5, 1853, but retroactive to July 1, 1853, roughly three months after completion of the through railway. Thus Berlin, New Hampshire, took its place on the map of railroad stations in the United States, for the first several months as part of the Atlantic & St. Lawrence and thereafter as a stop on the Grand Trunk Railway.

While all this occurred, a group of Portland businessmen formed a partnership under the name H. Winslow & Company in 1852 to purchase land on the west bank of the Androscoggin River at Berlin, New Hampshire, where they built a dam and erected a saw mill containing a gang saw and two single saws with a total daily capacity of 25,000 board feet of lumber. In 1853 the company built a store and a large boarding house for loggers and mill workers. Most significant, in 1854, with business booming, the company extended a short rail branch from the Grand Trunk to the sawmill plant. Apparently the lumber firm relied on the Grand Trunk's locomotives to switch cars in and out of the new industrial spur, but when Grand Trunk engines were unavailable, the firm employed oxen to move empty and loaded cars on the spur to the Grand Trunk. Later the company built its own private railway around the plant consisting of wooden rails covered with iron straps, with timber cars powered by horses and mules. This primitive little plant railway proved dangerous to operate, regularly sending employees to the company hospital, until the company replaced it with an ordinary railroad.

Eventually Nathan and Hezekial Winslow, who had lent his name to the enterprise, sold their interests to J.B. Brown, and Josiah Little died, leaving of the original partners only J.B. Brown and Little's widow. They took in men named Clemens, Bingham, and Warren in 1866 to form a new partnership--the Berlin Mills Company. Whether formally or informally, the railroad spur came to be called the Berlin Mills Railway, and eventually the plant trackage also came under that name. In 1868, William Wentworth Brown and Lewis T. Brown bought out not only J.B. Brown but also Clemens, Bingham, and Warren, establishing a family-owned firm that would survive for over a century.

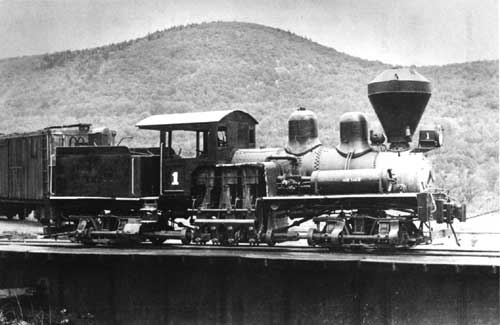

Harvey Brown of the Brown Company, owner

and operator of paper mills at Berlin, New Hampshire, personally took

the throttle of Berlin Mills Railway Engine No. 7, a 2-4-2T Vulcan,

hauling several flatcars with the "BCX" reporting marks of the Brown

Company, converted temporarily into excursion cars for a chemical

conference whose members were visiting the plant on June 22, 1926. The

photographer caught the locomotive between Berlin and Cascade from a

highway overpass. Trainmen wore borrowed Boston & Maine Railrod

uniforms for the occasion, since the Berlin Mills Railway normally

hauled no passengers.

Collection of Otis J. Bartlett.

By 1875 the Berlin Mills Company alone was daily sending a special lumber train of 22 cars to Portland, Maine. In 1888 the firm added a kyanizing plant to treat spruce lumber. By that time, in March 1888, the partnership arrangement that operated the company could no longer keep up with its growth, and the partners found it necessary to incorporate the Berlin Mills Company under the laws of Maine. That year the company also built the Riverside Groundwood Mill, whose 18 grinders rapidly ground wood into pulp. In 1891, downriver and across the stream, the company built the Riverside Paper Mill equipped with two machines that could produce 42 tons of newsprint daily. At the same time the Brown-family-controlled Burgess Sulphite Fiber Company built a plant on the east bank of the river to turn out wood fiber. In 1892 the Berlin Mills Company produced its first newsprint from pulp from the pulp mill.

Sometime amid all this progress, the Berlin Mills Railway acquired its first small steam locomotive, a switcher the company referred to as a "shifter" locomotive. The exact identity of what must have been the Berlin Mills Railway's first Locomotive No. 1 has become lost in the slash piles of the past, but in October 1891, the railway purchased its Locomotive No. 2, a Baldwin 0-4-0T with 44-inch drivers. The company added No. 3, another Baldwin 0-4-0T, in June 1893, this one about half the size of No. 2.

The original lumber mill burned in 1897, but the company replaced it with a mill capable of turning out 200,000 board feet of lumber per day. In 1898 the Berlin Mills Company built an electrochemical plant, as well as the Cascade Mill with four 164-inch paper-rolling machines. In December 1899, its railway division replaced the mysterious Locomotive No. 1 with a second Locomotive No. 1, an 0-4-0T built by the Pittsburg Locomotive Works. Presumably the company retired its original Locomotive No. 1 to the scrap pile upon receiving the new engine of the same number.

The Berlin Mills Railway celebrated the new century by purchasing its Locomotive No. 4, another Baldwin 0-4-0T in 1901. This and the three other locomotives seemed adequate to handle the business until 1904, when the Berlin Mills Company erected a window frame mill capable of turning out 2,000 window frames per day, and enlarged the Cascade Mill in capacity by 200 tons of paper. As a consequence of this expansion, that same year the company purchased second-hand from the Hastings Lumber Company at Bethel, Maine, its first 2-4-2T locomotive, a Baldwin product of February 1900, that became Berlin Mills Railway Locomotive No. 5.

It should be noted that although the Berlin Mills Railway's first 2-4-2T was its sixth locomotive, that particular Whyte system type dominated the logging railroads of the White Mountains of New Hampshire and Maine. C. Francis Belcher, who wrote the history of those railroads, described the 2-4-2T type as "the most popular and durable engine used in the mountains . . ." but was wrong m assuming all were Baldwin products.

Second-hand 2-4-2T No. 5 must have impressed management and employees of the Berlin Mills Railway as a great improvement over the 0-4-0T type, for the company was destined to purchase four more of them. It purchased No. 6, its first newly built 2-4-2T, from the Baldwin Locomotive Works in January 1906. In March 1907 they bought another, the third to be designated No. 1. Upon its delivery the company probably scrapped the 0-4-0T that had been the second No. 1. But for reasons unknown, the Berlin Mills Railway purchased its final three 2-4-2T engines from the Vulcan Iron Works in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.

An enlargement of Berlin Mills

Locomotive No. 7 shows the little locomotive lettered, probably in gold

or mustard color on both the cab and the saddle tank, "BERLIN MILLS

RAILWAY." The little 2-4-2T looked spic and span, decorated with four

American flags.

Collection of Otis J. Bartlett.

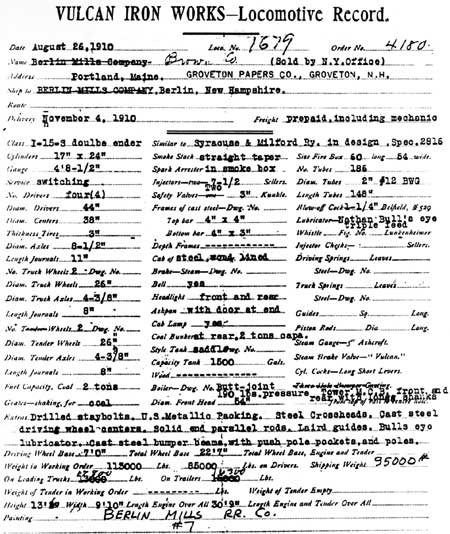

Berlin Mills Railway Locomotive No. 7 rolled out of the Vulcan Iron Works' erecting shop in January 1911 with builder's number 1679, featuring cylinders 17 inches in diameter with a 24-inch stroke and 44-inch-diameter drive wheels. (The Steamtown Foundation reported its builder's number was 1500, its cylinders 14 by 20, and its drivers 36 inches; Randolph Kean reported its builder's number to be either 1779 or 1500. All of these figures are believed to be in error.) Photographs made during the 1920s suggest that the company lettering on the sides of the saddle tank and below the cab windows on each side of the cab, which spelled out "BERLIN MILLS RAILWAY," may have been in gold leaf or in a mustard yellow imitating gold leaf. By that date, the locomotive bore no obvious trace of striping. Below the lettering, the sides of the cab also carried the locomotive's road number, apparently in the same color as the lettering.

In 1913, Locomotive No. 7 and its sisters were silent witnesses to the burning of the second sawmill plant at the Berlin Mills. The company chose this time to build as a replacement a "fireproof' plant of concrete with a slightly smaller capacity--150,000 board feet of lumber per day--milled by a single bandsaw instead of the previous pair. Apparently one reason for this retrenchment lay in the decline of the lumber industry, that, as far as the Berlin Mills Company was concerned, was far offset by growth of the paper business. The management of the Berlin Mills Company had gradually adopted a policy of producing itself the secondary raw materials the company needed. It produced not only lumber but the paper pulp needed to make paper. It eventually produced chemical byproducts, built its own plant at the Cascade Mill to produce aluminum sulphate used in sizing paper, built a press plant to make the steel ends for its fiber cores, and generally tried to be as self-sufficient as possible. By 1910 Scandinavian countries were producing kraft paper, and the Berlin Mills Company soon began producing it from pulp that came from a mill the company had built near La Tuque, Quebec, in 1909. In the process, the company gradually shifted away from its original emphasis on producing lumber to producing paper pulp from which it manufactured newsprint. Around 1917 it shifted away from newsprint production in favor of kraft papers and began also producing fine-quality bond papers.

It was during this 1917 expansion that the company purchased its second new 2-4-2T locomotive, its third of the type. It became a second No. 3. At this time the company probably scrapped the original No. 3, an 0-4-0T. That same year, World War I, which had begun in 1914, finally involved the United States. American as well as certain foreign customers of the Berlin Mills Company became increasingly anti-German, and when the United States entered the war, a wave of anti-German hysteria swept the nation. In that frantic atmosphere, self-proclaimed super-patriots attacked anything that seemed Germanic in character. They began to associate the name of the company, Berlin Mills Company, with the capital of Imperial Germany, and began to turn their business away from the company because of the innocent coincidence of the names; after all, the company had taken its name from the railroad station, which in turn was named for the Berlin Falls of the Androscoggin River. In response to this hysteria over anything even remotely Germanic, the directors on November 30, 1917, changed the name of the firm from the Berlin Mills Company to the Brown Company from the name of the family that owned it. The Berlin Mills Railway operated thereafter as a department of the Brown Company but retained its distinctive original name (under which it still operated in 1991). After the war, the Brown Company continued under its new name.

Eventual postwar prosperity led to the Berlin Mills Railway's purchase of its third Vulcan locomotive, 2-4-2T No. 8, built in May 1920. By this time the company produced many chemical products. As a byproduct, the electrolytic plant that produced chlorine used in bleaching papers also produced caustic soda. In 1908 the company ceased dumping waste caustic soda into the river and instead began marketing it as White Mountain Brand Caustic Soda. As another use for chlorine, the company began producing chloroform, much in demand as an anaesthetic in military surgery during World War I, and chlorides used in making military poison gas; vulcanizing rubber by a cold process; making artificial rubber and beginning in 1918, making carbon tetrachloride. In 1921 the company began turning out liquid chlorine, used principally in water purification, bleaching, and sewage disposal. In 1924, it started producing calcium arsenate, used by cotton producers to kill the boll weevil. Until 1914 the company had allowed the byproduct hydrogen to bleed off into the air, but beginning that year the firm used it to hydrogenate vegetable oils into the consistency of lard for use as shortening or as a frying agent in domestic cooking. A competitor halted that marketing with a patent-infringement lawsuit. During the war the company had built a plant to manufacture fiber powder containers for 6-inch guns. After the war the Brown Company used this plant to produce fiber-conduit to wrap underground electric cables. The market for this product spread rapidly throughout the United States and to Europe, and the company soon had to ship a full trainload of fiber conduit to Spain.

The list of new products being introduced seemed endless, and it was these that Berlin Mills Railway Locomotive No. 7 and her sisters switched around the plant trackage and down the spur line for shipment out over the Grand Trunk Railway. The Berlin Mills Railway's roster of motive power reached its peak during the 1920s--Moody's Manual of Investments for 1926 reported nine locomotives on the property to operate 3.75 miles of "main line" track (the spur to the Grand Trunk) and 13.75 miles of plant trackage, for a total track mileage of 17.50. The track consisted of a mixture of 65- and 70-pound (per yard) rail.

By 1929, the Brown Company had so expanded production that the railway division needed more motive power. The 2-4-2T type such as No. 7 finally had outlived its usefulness--the type was simply too small for the work now demanded of a locomotive, and the company sought heavier motive power from the Baldwin Locomotive Works. Locomotive No. 9, purchased in June 1929, and No. 10, bought after the beginning of the Great Depression in July 1930, featured the 2-6-2T wheel arrangement. They were, in effect, saddle tank "Prairie" locomotives. These engines apparently proved too heavy for the track of the Berlin Mills Railway, which as a consequence by 1932 had installed 72-pound rail and by 1933 had replaced it with 80-pound rail. Otherwise the 1930s were a decade of decline: The number of freight cars owned by the line dropped steadily from the 250 in 1932 throughout the rest of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s; yard trackage peaked at 16.11 miles in 1932, 1933, and 1934 (for a total mileage of 19.86), but dropped steadily thereafter until the mid-1950s. As a separate division of the Brown Company, the Berlin Mills Railway generally employed between 62 and 77 people during those decades.

Some of the earlier 2-4-2T engines continued to work alongside the heavier 2-6-2Ts, but one by one the company retired or sold them. From a total of nine locomotives on hand in 1926, the number had dropped to seven by 1929, six by 1936, to five in 1942. The time came for Locomotive No. 7 during World War II, for in November 1944, the Brown Company sold this locomotive to the Groveton Papers Company at nearby Groveton, New Hampshire.

The Groveton Papers Company originated as the Odell Manufacturing Company, which built a pulp mill with two digesters in Groveton, New Hampshire, in 1891. The company installed its first paper machine in 1893 (destined to be replaced in 1912), and a second in 1895 (destined to remain in production, incredibly, until 1975).

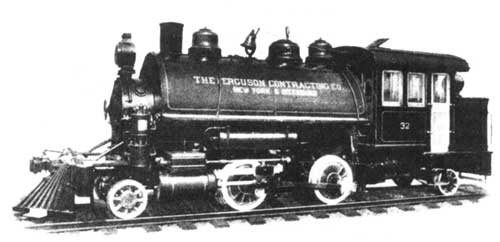

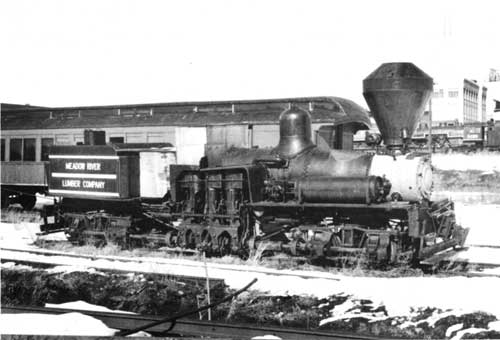

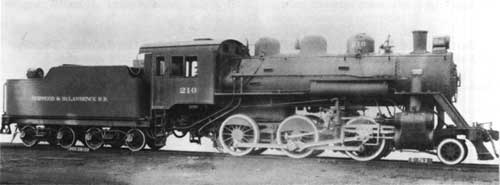

Groveton Papers Company saddletank

2-4-2T industrial switcher No. 7 had several owners and probably

appeared similar originally to the 2-4-2T built by the Vulcan Iron Works

in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, for The Ferguson Contracting Company. If

so, later it suffered replacement of her hardwood pilot with a

switchman's stepboard, the addition of steps from her pilot deck to her

running boards and a lowering of the deck of her cab beneath the

engineer's and fireman's seats. The photo above is from a Vulcan

catalog.

Above, Colorado Railroad Musuem Library, Below, collection

of Gerald Best, California State Railroad Musuem.

By 1901 the Groveton plant had sufficient yard trackage connecting with the Grand Trunk Railway to require a company locomotive, so to switch that yard trackage the Odell Manufacturing Company purchased from the Boston and Maine Railroad, on March 30, 1901, a third-hand 0-4-0 switch engine built in March 1884 as Eastern Railroad No. 15, which in 1890 had become Boston and Maine Railroad No. 115, named Binney. In November 1904, the Odell firm bought two more engines, second hand Boston & Maine No. 83, the Somerville, which became its No. 2; and on November 30, Boston & Maine No. 279, a genuine antique built by Hinkley & Drury in 1847 as Northern Railroad 4-4-0 No. 6, the Shaker, rebuilt in 1880 to an 0-4-0, sold to the Boston & Lowell Railroad in 1884 as No. 124, then sold back to the Northern Railroad in 1887 as No. 6, and later that year to the Boston & Maine as No. 279. This ancient piece of metal became Odell Manufacturing Company Locomotive No. 3.

In 1907 and 1908 Odell added a third paper machine, two more pulp digesters, and Hynie boilers. Paper machine No. 3 ranked at the time as one of the largest in the world. Business expanded accordingly, and in March 1912 the company, having scrapped engines No. 2 and 3 in 1910, purchased thirdhand its first 2-4-2T, a Baldwin product outshopped in January 1893 as Concord & Montreal second No. 25, which in 1895 had become Boston & Maine No. 725. This became Odell No. 4.

In 1913, the company built a bleach plant in order to enter the highly competitive market for white paper and bleached sulphite pulp.

In 1916, Odell company employees went out on a strike against the firm, and by the time the strike ended the company had been crippled and the town had lost most of its labor force; neither were to recover for nearly a quarter of a century. At the end of World War I the company did buy its only new engine, 0-4-0T No. 5, produced by American Locomotive Company at its Cooke Works in August 1918. Apparently management envisioned a postwar recovery which, as events turned out, failed to occur.

Beginning in 1919, the Brompton Pulp and Paper Company managed the Groveton plant, continuing to operate it at a minimal level until 1928. During that period, in 1921, the company scrapped its first locomotive, leaving it with only Nos. 4 and 5.

In 1928, the mill reverted to management of the Odell company, now owned by the Monroe family of Lewiston, Maine. The Monroes reorganized the Groveton plant as the Groveton Papers Company that same year. But the Great Depression began during the following year, and it became difficult to find enough business to keep paper machine No. 3 in service. After a decade of struggle, in 1939 the Monroes sold out to a family named Wemyss. Whether the new owners were merely lucky or prescient is unknown, but they put the long idle paper machine No. 3 back on line in 1940 and began turning out tons of paper products for which no market existed, storing the output in every available building in the town of Groveton. Of course, on December 7, 1941, the United States suddenly entered World War II, which created an instant market for the Groveton Paper Company's stored tons of paper products. Not only did military and government bureaucracy expand geometrically, but wartime priorities shut down much paper production or turned it to other military-related products. In November 1944, the Groveton Papers Company, in need of another 2-4-2T locomotive to replace its worn-out No. 4, built in 1893, purchased the Berlin Mills Railway's 2-4-2T No. 7. The company scrapped No. 4 in 945, which left it with Nos. 5 and 7. Groveton Papers Company did not renumber the No. 7 as its No. 6, so it apparently never had a locomotive No. 6.

After World War II, the Groveton mill experienced a short labor strike in 1946, but soon went back into production. During the early 1950s, while war raged in Korea, the company built a Semi-Chemical Plant that enabled the mill to use hardwood in the manufacture of pulp, which greatly boosted the economy of the area. A fourth paper machine installed in 1948 produced paper that the company converted to facial tissue and toilet tissue, as well as, eventually, napkins and towels. The paper business continued to change and evolve.

Groveton Papers Company retired Locomotive No. 4 on February 19, 1953, which left only No. 7 to switch the yard, and the latter clearly was nearing the end of its useful career. The company finally retired No. 7 on January 25, 1956, replacing it on April 17, with a secondhand 300-horsepower 45-ton General Electric diesel-electric locomotive built in September 1941.

The two surviving engines did not experience the burn of a scrapper's cutting torch. Eventually the company donated No. 5 to the town of Groveton, where it rests today in a small park.

In the summer of 1961, Francis Lamotte of West Lebanon, New Hampshire, organized a small steam tourist railroad called the Woodsville, Blackmount and Haverhill Steam Railroad. With Randolph Perkins and Donald McDonald, he spent two years planning the enterprise and on August 24, 1961, received permission of the New Hampshire State Public Utilities Commission to incorporate. The company issued stock to the amount of $100,000. It acquired abandoned right-of-way from the Boston and Maine Railroad extending from the end of the latter's operation in Blackmount to a place called Haverhill Station. This consisted of a stretch of about three miles of the old Woodsville-to-Plymouth main line of the Boston and Maine, in the heart of the White Mountains.

The Woodsville, Blackmount & Haverhill Steam Railroad then leased Groveton Papers Company No. 7, and by the spring of 1962 the new company had invested $2,000 in overhauling the engine. A retired railroader of Woodsville, Clyde O'Malley, became her engineer. The company also acquired a combination car from the Delaware & Hudson Railroad at Albany, New York, and a caboose from the Rutland Railroad, but due to a labor strike on the latter line, apparently never moved the caboose to the new trackage.

The new railroad was dedicated on Memorial Day, 1962, the featured speaker being F. Nelson Blount from Steamtown USA. That summer the Woodsville, Blackmount and Haverhill Steam Railroad operated its single locomotive and single car in round trips over three-quarters of a mile of track on Saturdays and Sundays during the summer months. The railroad operated again during the summer of 1963, but apparently that was the end of it.

The arched-roof Delaware & Hudson coach ended up on the Conway Scenic Railroad. Locomotive No. 7 remained idle for a number of years, though its owner did not move it back to Groveton. Then in 1969, the Groveton Papers Company delivered Locomotive No. 7 to the Steamtown Foundation at Bellows Falls, Vermont, as a donation to the foundation.

The two major corporations that once owned this locomotive went on to prosper after each had disposed of it. The Brown Company eventually was acquired by the James River Corporation, which continues to operate the paper mills at Berlin, New Hampshire, as of 1988; as one of its departments, the Berlin Mills Railway still functions. In fact, the railway took over additional trackage and acquired a large fleet of freight cars, as well as a number of diesel-electric locomotives. With this equipment, the Berlin Mills Railway reached its centennial year in 1990 (unless one considers 1954 to have been its true centennial).

The Groveton Papers Company also continued to produce paper. In 1968, Diamond International acquired the company and in turn was acquired by Sir James Goldsmith and associates, who sold out to the James River Corporation in 1983. This successor of the Odell Manufacturing Company also approached its centennial year, 1991.

The old 2-4-2T Locomotive No. 7, which served these corporations so well, survives as one of only four standard gauge 2-4-2T locomotives in the United States, a type once common on logging railroads. The National Railway Historical Society chapter in Atlanta, Georgia, owned one such engine that had belonged to a brick manufacturing company; a marine museum at Pensacola, Florida, exhibited another, and East Branch & Lincoln Railroad No. 5 rested in retirement at a ski area at Loon Mountain, New Hampshire.

Condition: Mechanical condition of this locomotive is unknown, but it is believed restorable to operating condition. A group of Steamtown Foundation volunteers cleaned and painted the locomotive in 1987.

Recommendation: Berlin Mills Railway Locomotive No. 7 is a fairly rare survivor of a once common type of locomotive used on logging railroads and industrial plant trackage, and it represents two New Hampshire paper manufacturing companies. The Berlin Mills Railway, still active nearly a hundred years after acquiring its first steam locomotive, and 134 years after its first rail was laid, has a long and unusual history for an industrial plant railroad. Researchers should prepare a report on the locomotive and should thoroughly investigate sources of Brown Company photographs of the engine in service, as well as other steam engines on the railroad. Researchers seek local sources of history to develop a more thorough understanding of the Berlin Mills Railway's history and of the Berlin Mills paper plant's history. The report should include the results of a thorough physical investigation of the engine, as well as of its various layers of paint, striping, lettering, numbers, and other decorations (unless it was stripped to bare metal before its last painting), equivalent to the physical history in a historic structure report. The report should also thoroughly investigate the history of the locomotive while in service for the Groveton Papers Company, and in particular ascertain whether or not the locomotive ever carried lettering of that company. Photographs of the locomotive on the Woodsville, Blackmount and Haverhill Steam Railroad indicate that the locomotive may have been repainted but was not lettered for that operation, and that fact needs to be confirmed, as well as whether or not the engine operated after 1963 on that line, and what happened to it thereafter until the Steamtown Foundation acquired it. The historian assigned to research and write this report should also seek out former engineers of the Berlin Mills Railway and the Groveton Papers Company to obtain oral history regarding operation of the locomotive. Upon completion of this report, the locomotive should be restored as Berlin Mills Railway No. 7, repainted, lettered and numbered in a historically accurate fashion for that railroad, with whatever color lettering and decoration documentary research and physical research determines was in use during the 1920s or earlier on engines of the Berlin Mills Railway.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Armstrong, Jack. Letter to author, June 5, 1988. Supplied partial motive power rosters (mostly diesel-electric) of the Berlin Mills Railway and Groveton Papers Company.

Bartlett, Otis J. Letter to author, April 14, 1988. Loaned photograph of Locomotive No. 7.

Belcher, C. Francis. Logging Railroads of the White Mountains. Boston: Appalachian Mountain Club, 1980.

"Berlin Mills Railway." The Short Line: The Journal of Shortline and Industrial Railroads, Vol. 13, No. 5 (Mar. 1986): 6.

Bolt, Jeff. The Grand Trunk in New England. Toronto: Railfare Enterprises, Ltd., 1986: 8-51, 64, 65, 86, 87.

Fielding, Ed. "Short Line Equipment: Berlin Mills." The Short Line: The Journal of Shortline and Industrial Railroads, Vol. 7, No. 5 (Sept.-Oct. 1979): 6.

________. "1979 Freight Car Survey." The Short Line: The Journal of Shortline and Industrial Railroads, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Jan.-Feb. 1980): 7.

Frye, Harry. Letters to author, June 1, 1988 and June 26, 1988. Supplied locomotive rosters of the Berlin Mills Railway, the Groveton Papers Company, the Whitefield & Jefferson Railroad, and the Johns River Railroad.

Guide to the Steamtown Collection. Bellows Falls, Vt.: Steamtown Foundation, n.d. (ca. 1979), Item No. 7 and locomotive roster entry.

Historical Committee. Berlin, New Hampshire, Centennial, 1829-1929. Berlin: n.p., n.d. [1929]: 40-45.

Kean, Randolph, The Railfan's Guide to Museum & Park Displays. Forty Fort: Harold E. Cox, Publisher, 1973: 174.

Lewis, Edward A. American Short Line Railway Guide. Strasburg: The Baggage Car, 1975: 56.

MacDow, Shirley, of Groveton Paper Board, Inc. Letter to author enclosing a three-page typescript entitled "The Groveton Mill Location, A Historical Outline."

Mead, Edgar T., Jr. Telephone communication with author, Apr. 12, 1988."A Memory of Years Long Past." Lewiston (Me.) Daily Sun, Aug. 6, 1964.

Moody's Manual of Investments, American and Foreign: Industrial Securities, 1930. New York: Moody's Investors' Services, Inc., 1930.

O'Malley, Frank C. Letter to author, dated Apr. 19, 1988, enclosing copies of three news clippings and two photographs regarding the Woodsville, Blackmount & Haverhill Steam Railroad.

Quinn, Michael. "West Lebanonite Starts Own Steam Railroad Co." Valley News, n.d. [ca. June 1962] (Lebanon, N.H.).

Rice, D.M. Letters to the author, Dec. 20, 1988, Mar. 27, 1989, enclosing photographs, locomotive roster, map under separate cover, and answering many questions and providing much additional information on the Berlin Mills Railway and its parent company.

Short-Line Annual, 1962-1963, 5th ed.

Smith, Arlie G. Letter to Edgar T. Mead, Jr., Mar. 30, 1970. Letter from vice president, Groveton Papers Company, to Steamtown Foundation, documenting donation of Locomotive No. 7 in December 1969.

"Transformation of a Tanker." Trains, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Dec. 1963): 9.

Wallin, R.R. "The Shortline Scene." Extra 2200 South, The Locomotive Newsmagazine, Vol. 9, No. 3 (Jan.-Feb. 1972): 30.

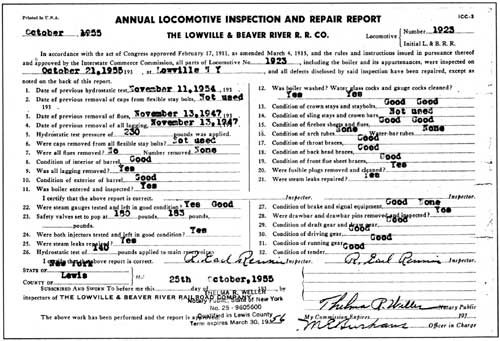

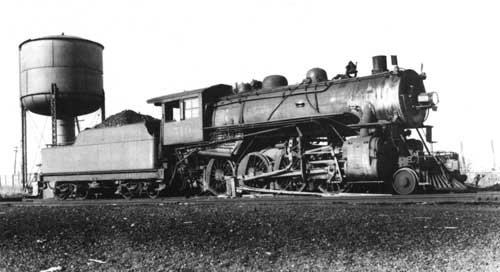

BOSTON AND MAINE RAILROAD NO. 3713

Owner(s):

Boston and Maine Railroad 3713

Whyte System Type: 4-6-2 Pacific

Class: P-4a, Series 3710-3714

Builder: Lima Locomotive Works

Date Built: December 1934

Builder's Number: 7625

Cylinders (diameter x stroke in inches): 23 x 28

Boiler Pressure (in lbs. per square inch): 260

Diameter of Drive Wheels (in inches): 80

Tractive Effort (in lbs.): 40,900; with booster, 52,800

Tender Capacity:

Coal (in tons): 18

Oil (in gallons): not applicable

Water (in gallons): 12,000

Weight on Drivers (in lbs.): 209,800

Remarks: After delivery, engine was the subject of a New England wide name contest that resulted in it being named The Constitution. Engine has a superheater and a steam booster on the trailing truck.

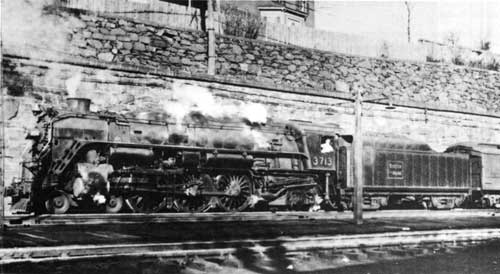

Boston and Maine Railroad 4-6-2 Locomotive No. 3713

History: Created by a consolidation in 1842 of earlier railroads, including one dating back to 1835, the Boston and Maine Railroad by 1920 owned 1,704 miles of track in Massachusetts, Maine, Vermont, New York, and New Hampshire and leased an additional 527 miles of track of other railroads. As of 1917, it owned 1,131 locomotives, 1,900 passenger cars, and 22,887 freight cars, and would continue to serve as an important regional rail system.

The Baldwin Locomotive Works produced the first 4-6-2 type of locomotive in 1901, allegedly as an improvement on the 4-4-2 or Atlantic type, and because of that, plus the fact that Baldwin's first 4-6-2 was erected for export to New Zealand Railways on an island in the Pacific, the new type of locomotive came to be called a Pacific type. (Another point of view would have the 4-4-2 an improvement over the 4-4-0, and the 4-6-2 an improvement over the "10-wheeler" type 4-6-0.)

The Boston and Maine Railroad purchased its first 4-6-2 type locomotives in 1910, ordering a dozen of these locomotives from Schenectady. The company assigned these to the class P-1. In 1911 the company purchased another 40 of these Schenectady engines with some minor changes that resulted in their being classified as P-2-a types. In 1913 the company purchased another 20, with further variations that led to their being classified as the P-2-b. In 1916 came another 10 of a still different class, the P-2-c. In 1923 the company acquired a final 10 from Schenectady, these classified as the P-3-a, making a total of 92 Pacifics purchased from the American Locomotive Company's Schenectady Works.

On the Boston and Maine, the Pacifics became the mainstay of passenger service from 1910 until dieselization, replacing little 2-6-0 Moguls and 4-6-0 10-wheelers on the main lines and shunting them aside to branch line traffic. Some were modernized over the years with either Elesco or Worthington feedwater heaters and power reverse levers.

Photo courtesy Boston & Maine

Railroad Historical Society

Meanwhile, the Lima Locomotive Works was developing a reputation for manufacture of exceptionally powerful main line steam motive power equipped with the latest improvements such as high-pressure boilers, feedwater heaters, and other mechanical innovations that led to their being called "superpower" steam locomotives. In 1934, the Boston and Maine Railroad contracted with Lima for construction of five locomotives of the 4-6-2 Pacific type, to be numbered in the series 3710 through 3714. Lima delivered these locomotives in December 1934. These first five Lima engines, which the Boston and Maine classified as their P-4-a type, worked so well that the company ordered another five from Lima in 1936. These, delivered in March 1937, proved to be the last Pacifics that Lima would ever build. The last five Pacifics acquired by the Boston and Maine varied slightly from the earlier ones and became the P-4-b class, Nos. 3715 through 3719.

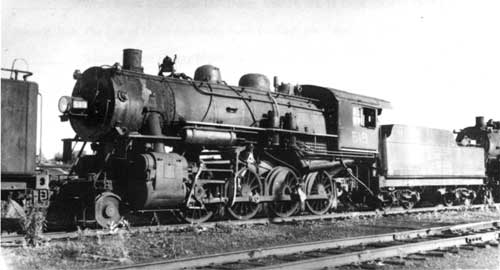

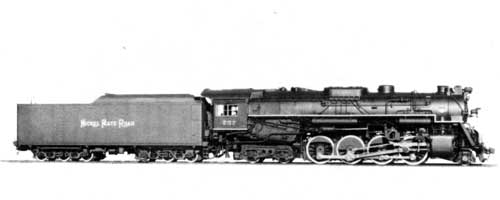

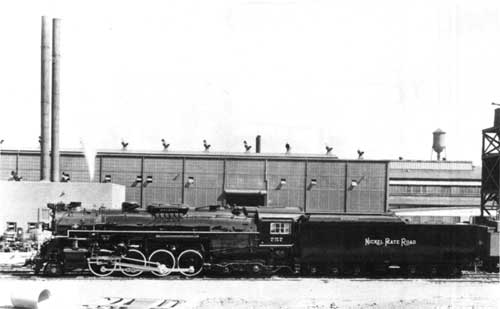

The Lima Locomotive Works photographed

the engineer's side of Boston & Maine Locomotive No. 3710 as

representative of all of the engines in the series 3710-3714. This

builder's photograph illustrated the original streamlining features of

this class such as the smoke deflectors alongside the smokebox and the

casing that concealed the steam and sand domes and whistle. Shortly

after its construction, the railroad gave No. 37 13 the name The

Constitution, which it carried on a pair of name plates mounted just

below the running boards and above the third pair of drive wheels. This

beautiful machine, well designed aesthetically as well as mechanically,

is shown below, on her home railroad after the railroad had removed the

streamlining of engines of this class. In this view the locomotive is

temporarily out of service, with her stack sealed to keep out the

weather. Above, Steamtown National Historic Site. Below, collection of

Gerald Best, California State Railroad Museum.

Locomotive No. 3713 is, of course, one of that first group of Lima Pacifics, a P-4-a that cost the company $100,000. She was inspected by C. W. Bruening at the Lima plant on December 21, 1934. As originally delivered, the locomotive had a metal shroud concealing her sand and steam domes and had smoke deflectors alongside the smokebox (some varieties of which were colloquially referred to as "elephant ears"), and a single, deck-mounted air pump on the pilot deck. As thus delivered, the engine had a semi-streamlined appearance.

Locomotive No. 3713 and her sisters went into service hauling the most important passenger trains on the Boston & Maine, eventually serving between Boston, Massachusetts, and Bangor, Maine; between White River Junction and Troy, New York; between Worcester, Massachusetts, and Portland, Maine; and between Springfield, Massachusetts, and White River Junction, Vermont. She was designed to operate at a normal speed of 70 miles per hour. She carried sufficient coal to pull and heat a 14-car train about 250 miles, and enough water to last about 125 miles.

When the Boston and Maine took delivery of its second order of Lima Pacifics in 1937, it sponsored a contest among New England schoolchildren to name those 10 engines and 10 other passenger engines. The contest was open to any pupil in any community along the railroad and included students from kindergarten to the final year of junior high school. The railroad promised to paint the names on the sides of the locomotive and to attach to the locomotive a plate with the name of the boy or girl who suggested the name, as well as the name of his or her school. The contest elicited more than 10,000 names for the 20 engines. A 14-year-old named J. Schumann Moore of Lynn, Massachusetts, a student at Lynn's Eastern High School, suggested the winning name for No. 3713: The Constitution. Other winning names for the 10 Lima Pacifics were for No. 3710, Peter Cooper No. 3711, Allagash; No. 3712, East Wind; No. 3714, Greylock, No. 3715, Kwasind; No. 3716, Rogers' Rangers; No. 3717, Old North Bridge; No. 3718, Ye Salem Witch; and No. 3719, Camel's Hump.

Certainly The Constitution was among the more dignified names. Moore said he selected the name because it signified "the backbone of our country. Appropriate especially in that the railroads are the backbone of our transportation system." On December 11, 1937, the railroad held a christening ceremony in Boston's North Station. The railroad would hold two more such contests, one in 1940 and one in 1941, to name eight additional engines. For all 31 named engines, the engine name and the name of the contest winner were inscribed on a pair of large name plates mounted on the running boards on both sides of each engine above the drive wheels. Thus engine No. 3713 and her sisters acquired names, a practice more typical of the 19th than the 20th century in railroad operation.

Collection of Andy Kinicki.

After the country entered World War II in 1941, No. 3713 pulled many a 15- to 20-car troop train during the next four years. It was apparently during these wartime years that, for reasons unknown at present, the Boston and Maine removed both the shroud atop the boiler of these five locomotives, and the smoke deflectors alongside the smokeboxes. They may simply have been removed for routine servicing and, in the press of wartime conditions, were left off to avoid the time and labor of putting them back. About 1944 or 1945, the company added a second air pump on the pilot deck.

It was probably after the war that No. 3713 and her sisters were repainted and relettered in a racy style sometimes referred to as "speed" lettering because its slanted script gave an impression of speed. The "speed" lettering replaced the standard rectangular herald adopted by the Boston & Maine in 1927.

Following the war, No. 3713 and her sisters returned to handling the regular passenger traffic. Among their patrons were young campers headed for an outing in the northern woods. Toward the end of her working life, No. 3713 was equipped with special steam pipes and used to melt snow in the yards of North Station, and still later as a stationary steam power plant. She was last called into service during a flood. Whereas floods shorted out the axle-mounted traction motors of diesel-electric locomotives, the fireboxes of many steam locomotives rode high enough to be above flood waters so that steam locomotives could push through flood waters that diesels dared not enter. No. 3713 made her last run in 1958.

When F. Nelson Blount acquired No. 3713, he exhibited her first at South Carver, then Pleasure Island at Wakefield, Massachusetts, in 1960 and 1961. From 1962 through 1969, the engine rested on exhibit first at North Walpole, New Hampshire, then at Bellows Falls, Vermont, after which Steamtown loaned the engine to Boston's Museum of Science. The Boston and Maine's Billerica Shop overhauled the locomotive in 1969, repainting her in the original 1934 herald (pattern of 1927). Eventually, after some years in Boston, the engine returned to Steamtown during the mid-1970s.

The 4-6-2 Pacific-type locomotive is the type most common in the Steamtown collection, which in addition to this engine included one Canadian National Railways 4-6-2, No. 5288, and two Canadian Pacific Railway Pacifics, Nos. 1293 and 2317.

C. P. Atherton photo, collection of

John C. Hutchins, courtesy Boston & Maine Railroad Historical

Society

However, Boston and Maine Railroad No. 3713 is the only American-built engine among the Pacifics in the Steamtown collection. It is one of about fifty-six 4-6-2 Pacific-type locomotives preserved in the United States. Although the type is well represented among preserved locomotives in the United States and 12 more are preserved in Canada this particular locomotive is further significant because it is one of only three steam road engines of the Boston and Maine Railroad that have survived, the others being 4-4-0 No. 494, at White River Junction, Vermont, and 2-6-0, No. 1455, at Edaville, Massachusetts. Two Boston and Maine 0-6-0 switch engines, Numbers 410 and 444, also survive.

Condition: In terms of appearance, the locomotive is in reasonably good condition. Mechanically, the locomotive is believed to be nearly operable. It could be made operable with suitable overhaul.

Recommendation: This is exactly the type of heavy-duty, main line motive power, in this instance specifically passenger motive power, that the Steamtown collection should emphasize. The NPS should document in much more detail the operational history of this locomotive, and through photographs and Boston and Maine Mechanical Department records, should thoroughly explore changes made in the locomotive during its history. Extensive search for photographs of this particular locomotive in service should be a part of the study. The study should include a complete assessment by mechanical authorities of the locomotive's mechanical condition. The report should recommend the period to which the locomotive should be restored and repainted, and based on mechanical condition, whether to restore it to operable condition and to operate it for excursion trains or special movements. It should ascertain whether the locomotive ever received the red and mustard/gold striping and speedlining documented on sister locomotives Nos. 3712 and 3714. It should be restored to operation if feasible. When not in service, it should be exhibited indoors, protected from the weather.

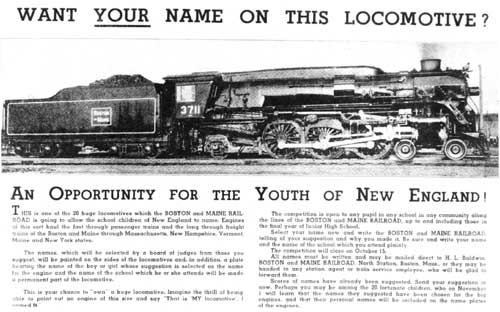

The Boston and Maine Railroad published

this undated single-sheet flyer during the mid 1930s to announce the

contest to select names for its Lima-built 4-6-2 locomotives. The flyer

illustrated No. 3711, a sister to Steamtown's No. 3713, which exhibited

the smoke deflectors alongside the smokebox and the streamlined casing

over the domes, features removed from all locomotives of this class,

probably during World War II.

Steamtown Foundation

collection.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Armitage, Al. "Boston and Maine Locomotive No. 3710 [measured drawing]." Railroad Model Craftsman, Vol. 25, No. 2 (July 1956): cover, iii.

"Boston and Maine 4-6-2 [measured drawing of No. 3712]." Model Railroader, Vol. 13, No. 4 (Apr. 1946): 266-268.

"Boston and Maine No. 3712 [measured drawing]." Model Railroader, Vol. 17, No. 5 (May 1950): 60.

Boston & Maine Railroad, WANT YOUR NAME ON THIS LOCOMOTIVE? AN OPPORTUNITY FOR THE YOUTH OF NEW ENGLAND. (Single-page promotional flyer, published by the Boston and Maine Railroad, ca. 1937.) In the Steamtown Foundation files.

Cook; Richard J. Super Power Steam Locomotives. San Marino: Golden West Books, 1966: 7, 8, 21, 42, 43, 100, 101.

Frye, Harry A. Minuteman Steam: Boston & Maine Steam Locomotives, 1911-1958. Littleton: Boston & Maine Railroad Historical Society, Inc., 1982: 124-142, 158, and especially 125, 140-142. [This excellent motive power history is a principal source on this locomotive.]

Guide to the Steamtown Collection. Bellows Falls, Vt.: Steamtown Foundation, n.d. (ca. 1973).

Harlow, Alvin F. Steelways of New England. New York: Creative Age Press, 1946.

Hastings, Philip Ross. The Boston and Maine: A Photographic Essay. n.p.: Locomotive and Railway Preservation, 1989. [Disappointingly, although Hastings photographed No. 3713, not one of his photographs of that locomotive appears in this book.]

"High Green" column, Boston and Maine Railroad Magazine, Vol. 26, No. 3 (May-June-July 1958). [Item on upcoming move of Locomotive No. 3713 to Edaville.]

Johnson, Ron. The Best of Maine Railroads. South Portland: Author, 1985: 120.

Jones, Robert Willoughby. Boston and Maine; Three Colorful Decades of New England Railroading. Glendale: Trans-Anglo Books, 1991: No data on Locomotive No. 3713, but on pp. 50 and 86 color photos of No. 3712 and on p. 51 of 3714 all with colorful red and mustard-gold lettering and striping which may have been used on No. 3713 also.

Kyper, Frank. "Yes, It Was 'The Constitution.'" The Railroad Enthusiast (Winter-Spring 1971): 27-28.

________. "The Boston and Maine's Existing Steam Locomotives--Intentional and Otherwise!" B&M Bulletin, Vol. 2 (Mar. 1973): 10-14.

Lima Locomotive Works. Builder's photo card of Locomotive No. 3710, with specifications for series 3710-3714 on reverse. In Steamtown collections.

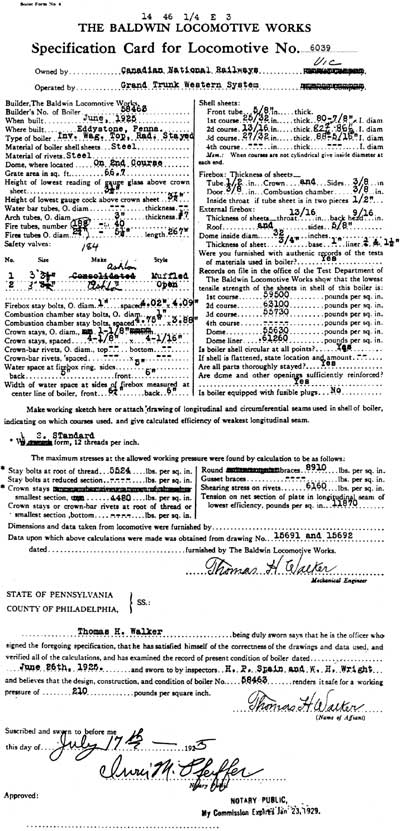

Lima Locomotive Works. "Specification Card for Locomotive No. 3713." Dec. 21, 1934. In the Steamtown Foundation files.

Locomotive Cyclopedia of American Practice. 12th ed. New York: Simmons-Boardman Publishing Corp., 1944:171. [Builder's photograph of No. 3710 with specifications.]

McCall. "Pinnacle of the Pacifics--Boston & Maine's P4 Locomotives." B&M Bulletin, Vol. 17, No. 3, n.d. [1990]: 14-35.

Neal, Robert Miller. High Green and the Bark Peelers: The Story of Engineman Henry A. Beaulieu and his Boston and Maine Railroad. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1950: 161-165. [A description of a trip on P-4-b No. 3715 in service on a suburban (commuter) train of wooden coaches.]

"Retired Boston and Maine Equipment on Exhibit at 'Pleasure Island.'" Boston and Maine Railroad Magazine, Vol. 27, No. 4 (July-Aug. 1959): 16, 17.

3713, the Pacific Locomotive exhibited at the Museum of Science, Boston. Boston: Museum of Science, n.d. [A six-panel folder about the locomotive.]

Twombly, L. Stewart, and Robert E. Chaffin. "Post-1911 B&M Steam Roster--Part XI." B&M Bulletin, Vol. 6, No. 1 (Fall 1976): 34.

BROOKS-SCANLON CORPORATION NO. 1

Owner(s):

Carpenter-O'Brien Lumber Company 1

Brooks-Scanlon Corporation 1

Lee Tidewater Cypress Company 1

J.C. Turner Lumber Company 1

Whyte System Type: 2-6-2 Prairie

Class: (unknown)

Builder: Baldwin Locomotive Works

Date Built: August 1914

Builder's Number: 41649

Cylinders (diameter x stroke in inches): 16 x 24

Boiler Pressure (in lbs. per square inch): 175

Diameter of Drive Wheels (in inches): 42

Tractive Effort (in lbs.): 20,800

Tender Capacity:

Coal (in tons):

Water (in gallons):

Weight on Drivers (in lbs.):

Remarks: Engine could burn either coal or wood; engine has a second sand dome behind the steam dome, ahead of the cab. This locomotive may have had a Rushton or cabbage stack, especially under its second owner. This is a tired, worn-out locomotive.

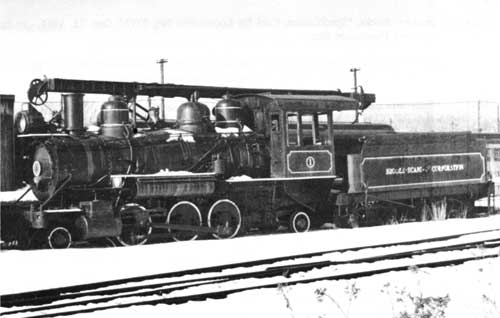

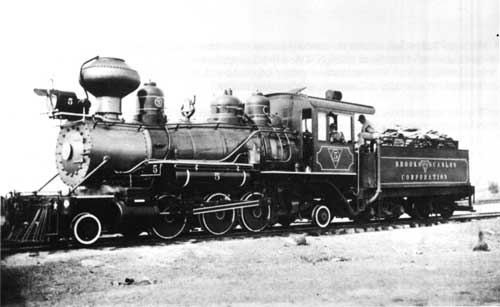

Brooks-Scanlon Corporation 2-6-2 Locomotive No. 1

History: The 2-6-2 Prairie-type locomotive took its name and initial popularity from its use in relatively fiat prairie country such as the Great Plains in Kansas and surrounding states. About 50 locomotives of this type have survived nationwide, 15 of them veterans of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway, a company that made particularly extensive use of the type. But as time passed, Prairie locomotives also developed popularity among lumber companies operating in relatively fiat forest country. The only example in the Steamtown collection of an engine with this wheel arrangement underwent the latter use; it was built for a lumber company's logging railroad and eventually passed through the hands of several Florida lumber firms during its active career. So it was essentially an industrial locomotive, though many engines of this type served on common carrier railroads.

Controlled by the William J. O'Brien family of St. Paul, Minnesota, the Carpenter-O'Brien Lumber Company was incorporated under the laws of Delaware in May 1913 but with operations in Florida, and apparently ordered this locomotive as its No. 1, which Baldwin Locomotive Works outshopped in 1914.

Carpenter-O'Brien built a fine sawmill plant Eastport, Florida, to mill pine logs, and even had a ship built to haul 2 million board feet of lumber per trip to its yard on Staten Island, New York. American entry into World War I in 1917 resulted in the sale of the S.S. William J. O'Brien, which in turn may have triggered sale of the Florida mill plant and timber holdings to the Brooks-Scanlon Corporation.

In 1896 the Brooks and Scanlon families, also of Minnesota, consisting of Dwight F. Brooks, M.D., Lester R. Brooks, Anson S. Brooks, and M.J. Scanlon, went into business together in Minneapolis, operating sawmills first at Nickerson, then at Cass Lake, Minnesota, and incorporating the Brooks-Scanlon Lumber Company in 1901 to operate a large plant the firm erected in Scanlon, Minnesota, served by the subsidiary Minnesota and North Wisconsin Railroad.

In 1905, the founders of the firm scouted timber in the Pacific Northwest, purchasing two large blocks of Ponderosa pine timberlands in Deschutes County, Oregon. In 1910 the plant at Scanlon, Minnesota, ran out of timber to mill, so the company moved to Oregon, with the headquarters remaining in Minneapolis.

In 1905, the firm also purchased tracts of Southern pine near Kentwood, Louisiana, where it erected another sawmill plant, served by the subsidiary Kentwood and Eastern Railroad.

By 1917 it was apparent to Brooks-Scanlon management that its Louisiana plant eventually would run out of timber (which it did in 1923). The company bought out Carpenter-O'Brien's holdings and its Eastport, Florida, mill, in the process acquiring Locomotive No. 1. Brooks-Scanlon took over at Eastport on December 31, 1917. By 1928 the company owned or controlled approximately 400,000 acres of timberlands located in Lafayette, Taylor, Madison, and Jefferson counties, Florida. At that time the firm had sawmills with a capacity of turning out 100 million board feet of lumber per year, as well as a planing mill, dry kilns, storage sheds, warehouses, and headquarters for a logging railroad at Eastport, 13 miles from Jacksonville on Florida's St. Johns River, with deep-water decking facilities to accommodate ocean going vessels. Officers included M.J. Scanlon, president, with offices in Minneapolis, Minnesota; J.S. Foley, vice president, located at Eastport; A.S. Brooks, treasurer, and P.A. Brooks, secretary, the latter two officers also headquartered in Minneapolis.