|

Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site Alabama |

|

NPS photo | |

Taking to the Sky

On a warm July day in 1941, 13 young African American men arrived at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama to begin their training as Army Air Corps pilots. They were a long way from earning their wings, and not all would make it, but the chance to try was itself a victory, something for which African Americans had long fought. Though they had exhibited ability and courage in military conflicts from the Revolutionary War to World War I, most African Americans were either denied the chance to serve or assigned menial noncombatant roles with no chance for advancement.

The idea that they could meet the high standards of military aviation generated the fiercest resistance of all. In their training at Moton Field, however, and in combat during World War II, the Tuskegee Airmen conclusively demonstrated the skill, bravery, quick thinking, and coolness under pressure demanded of a combat pilot. As they had done so many times before, when finally given the opportunity, African Americans flew in the face of assumptions, proving they were equal to the task.

"Our mantra was that we dared not fail..."

—Charles Dryden, student at Moton in 1942

The booming field of aviation in America was mostly closed to African Americans in the early 1900s, and they were entirely excluded from military aviation. Then in 1939, in response to growing international tensions, Congress passed the Civilian Pilot Training (CPT) Act, designed to turn out large numbers of pilots who could move quickly into military aviation if needed. CPT programs were established at colleges around the country. Through the efforts of the National Airmen's Association of America, an organization of African American pilots, six black colleges, among them Tuskegee Institute, and one private flying school were included. In May 1940 the first class of CPT pilots completed their elementary flight training at Kennedy Field, near Tuskegee. The program was so successful that it expanded to include more advanced CPT programs, becoming the center of African American flight training in the South.

The U.S. Army Air Corps (AAC) still refused to allow African Americans to apply for flight training. Two important developments helped overcome its resistance: Public Law 18 of April 1939 required the AAC to contract with civilian flight schools for primary training of military pilots, and one of the schools had to train African Americans. The Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 prohibited discrimination in training for military service. This legislation, along with pressure from the black press and civil rights organizations and support from Eleanor Roosevelt, led to the establishment of the segregated 99th Pursuit Squadron in January 1941.

Tuskegee was chosen because of its success in the CPT program, its climate suitable for year-round flying, and the school's experience in conducting education in a segregated environment. The squadron would be made up primarily of African Americans training at two new air fields: Tuskegee Institute's Moton Field for primary training and Tuskegee Army Air Field (TAAF) for basic and advanced training. Since both of these facilities were segregated, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) opposed the plan. Others countered that segregated training was the best that could be hoped for at that time. Moton Field and TAAF were the sole training facilities for African American pilots throughout the war. They achieved what they did against a background of continuing racism and segregation in Tuskegee and at overseas bases.

RED TAIL ANGELS

Of the first class of 13 candidates who began training in July 1941, five survived the rigorous programs at Moton and TAAF to earn their wings on March 7, 1942. Four received their commissions as 2nd lieutenants. Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., already an Army captain when he arrived at Tuskegee, was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and given command of the 99th. As the nation stepped up the war effort and new classes rapidly completed the Tuskegee program its success spurred the AAC to form two more segregated units, the 332nd Fighter Group (initially made up of the 100th, 301st, and 302nd fighter squadrons) and the 477th Bombardment Group B-25 Medium. By the end of the war 992 pilots—later known as the Tuskegee Airmen—had been trained. About 17,000 African American men and women were trained for service in the AAC, including mechanics, communications and electrical system specialists, armament specialists, medical technicians, cooks, administrative clerks, parachute riggers, air traffic controllers, flight instructors, bombardiers, and navigators.

In April 1943 the 99th Fighter Squadron (the AAC "Pursuit" designation now "Fighter") was sent to North Africa to fly P-40s on patrol and bomber escort missions. The squadron shot down its first enemy aircraft in July, but also lost two pilots—the first of 66 Tuskegee Airmen killed in action or in accidents. The pilots proved their skills in bombing and strafing raids and providing air support over Italy, downing 12 German planes in two days. The 332nd Fighter Group, sent to Italy in early 1944, shot down at least 17 enemy aircraft during the Anzio campaign. The squadrons of the 332nd, now commanded by Colonel Davis, quickly gained a reputation as excellent escort units—along with the 99th the only ones to never lose a bomber. Bomber crews called them the "Red Tail Angels" because of their planes' distinctive red tail sections and because they were known to never abandon bombers in their care.

In July 1944 the 99th joined the 332nd and the expanded group began flying the P-51—the best U.S. fighter plane of the war. Their primary duty was to escort bombers to oil refineries and other strategic targets in Europe. During a bombing run in 1945, three pilots downed three of Germany's fast new Messerschmitt jet fighters. The war with Japan ended before the 477th Bombardment Group had a chance to see combat. But in April 1945, at Freeman Field in Indiana, pilots from the 477th were arrested for peacefully protesting the segregated officers' club. Their stand, along with the superb performance of the fighter squadrons, helped convince President Harry Truman to sign Executive Order 9981 in 1948 calling for "equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion, or national origin."

Moton Field 1941-1945

This was the place where we learned to fly, we became pilots, we became officers

—Randolph Edwards, 2003

In 1939 Tuskegee Institute was using a borrowed field to train pilots in the Civilian Pilot Training Program. When the Army Air Corps (AAC) awarded Tuskegee Institute a contract to provide primary flight training to African Americans, the need for a new field grew more pressing. Funding the field, however, remained an obstacle. Dr. Frederick Douglass Patterson, president of Tuskegee, asked the Julius Rosenwald Fund to hold its annual meeting at the school, hoping to persuade the foundation to lend Tuskegee the money. Fortunately for Tuskegee, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was on the foundation board.

While at Tuskegee in March 1941, Mrs. Roosevelt met Charles "Chief" Anderson, head of pilot training at Tuskegee. Noting that some people believed African Americans "can't fly airplanes," she asked Anderson for a ride. Her post-flight remark "Well, you can fly all right!" and the photo of the smiling Roosevelt in the airplane with Anderson provided a great boost to African American aviation. The Rosenwald Fund agreed to lend Tuskegee the money to construct their new airfield, named Moton Field after the school's second president Robert R. Moton. The AAC also designated it Tuskegee Army Primary Flying Field.

G.L. Washington, director of Tuskegee's Department of Mechanical Industries, and Tuskegee architect Edward C. Miller designed the structures, while African American architect Archie A. Alexander built the airfield. The landing strip was completed by fall 1941, but bad weather and drainage problems often forced the first class of cadets to use another field. To speed completion, student laborers and skilled workers from Tuskegee Institute pitched in. Throughout the war every African American AAC pilot received his primary training at Moton, bused here daily from cadet barracks on the Tuskegee campus.

From 1942 the Cadet House housed the cadet ready room and offices for the Flight Surgeon and Air Dispatcher. It later was headquarters for the civilian flight instructors.

Army Supply Building This structure was the distribution center for aircraft parts and supplies. From 1942 it was occupied by the Army Supervisor's staff.

Hangar No. 1, completed in 1941, was the center of operations. Around the open hangar area were briefing rooms, administrative offices, and maintenance shops.

Auxiliary Storage Shed This wood frame storage locker held ground maintenance equipment and nonflammable items used by Moton Field personnel.

Bath and Locker House Completed in 1944, this building provided improved lavatory, bath, and locker facilities for the men and women serving at Moton Field.

The Skyway Club was built in 1945 as a recreational facility serving all military ranks and civilians. It provided food service and had a large hall for leisure and social gatherings.

Hangar No. 2 was completed in in response to expanding operations. Here were the field's control tower and a parachute packing area. It burned in 1989.

From the Control Tower dispatchers controlled flight operations using loudspeakers and a system of light signals. It doubled as a parachute drying tower.

Physical Plant This building housed offices for the Plant Engineer and staff. Special equipment and parts for climate, water, and electrical systems were stored here.

Warehouse This concrete block structure, built at the same time as Hangar No. 2, housed non-aviation supplies and offices for the Construction Supervisor and staff.

Visiting Moton Field Today

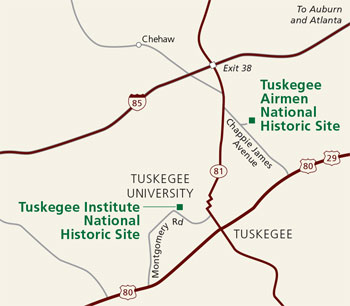

(click for larger map) |

Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site is open daily 9 am to 4:30 pm CST except Thanksgiving, December 25, and January 1. There are no entrance fees. For groups of 10 or more, please make reservations at least one week in advance.

What To Do A temporary visitor center houses exhibits, a bookstore, and a theater where five historic films are shown. Hangar No. 1 also contains exhibits and historic airplanes.

If you visit the weekend before Memorial Day you can watch the annual Tuskegee Airmen Fly-In, sponsored by the Negro Airmen International and the City of Tuskegee. The Fly-In is open to the public and features visits by original Tuskegee Airmen of WWII, historic aircraft, military fly-bys and aerobatics, exhibits, and vendors.

Directions From Montgomery, Ala., follow I-85 North to exit 38 (Tuskegee-Notasulga). Turn right on Hwy. 81; travel one mile. Turn left on Chappie James Ave. (alternative route 81); travel ¾ mile to the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site parking lot on the left.

From Atlanta, Ga., follow I-85 South to exit 38 (Tuskegee-Notasulga). Turn left on Hwy. 81; travel one mile. Turn left on Chappie James Ave. (alternative route 81); travel ¾ mile to the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site parking lot on the left.

Accessibility Groups with special-needs visitors should contact the park at least three weeks in advance.

Tuskegee University is a historically African American university founded by Booker T. Washington in 1881. Called Tuskegee Institute until 1985, the school was behind the creation and civilian operation of Moton Field. Flight cadets slept in school dorms and received preflight training here. Visit Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site for exhibits, films, and ranger-led tours of The Oaks, home of Booker T. Washington.

Tuskegee Airmen Inc. is dedicated to preserving the memory of America's first African American military airmen. The organization honors the accomplishments of all African Americans who participated as air crewmen, ground crew, and operations support personnel in the Army Air Corps during World War II.

Congressional Gold Medal

In 2007 the Tuskegee Airmen received the highest civilian award bestowed

by the nation, the Congressional Gold Medal of Honor. At the award

ceremony in the U.S. Capitol rotunda, a Congressional Gold Medal was

awarded "on behalf of the Tuskegee Airmen, collectively, in recognition

of their unique military record, which inspired revolutionary reform in

the Armed Forces." Surviving Tuskegee Airmen or their heirs received a

bronze replica of the medal. The original is displayed in the

Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum.

Source: NPS Brochure (2008)

|

Establishment Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site — November 6, 1998 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Foundation Document, Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site, Alabama (April 2017)

Foundation Document Overview, Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site, Alabama (January 2017)

General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site Final (2010)

Historic Furnishings Report: Moton Airfield, Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site (Mary Grassick and Carol Petravage, 2006)

Long Range Interpretive Plan: Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site (October 2003)

Preservation/Restoration of Moton Field: Phase II

Cultural Landscape Report, Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site (The Jaeger Company, 2002)

Historic Structure Report: Army Supply Building, Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site (The Jaeger Company, 2002)

Historic Structure Report: Bath & Locker House, Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site (The Jaeger Company, 2002)

Historic Structure Report: Cadet Class & Waiting Room, Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site (The Jaeger Company, 2002)

Historic Structure Report: Dope Storage Room, Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site (The Jaeger Company, 2002)

Historic Structure Report: Entrance Gate, Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site (The Jaeger Company, 2002)

Historic Structure Report: Fire Protection Shed, Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site (The Jaeger Company, 2002)

Historic Structure Report: Guard Booth, Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site (The Jaeger Company, 2002)

Historic Structure Report: Hangar Number One, Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site (The Jaeger Company, 2002)

Historic Structure Report: Hangar Number Two, Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site (The Jaeger Company, 2002)

Historic Structure Report: Oil Storage Shed, Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site (The Jaeger Company, 2002)

Historic Structure Report: Vehicle Maintenance Shed, Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site (The Jaeger Company, 2002)

Historic Structure Report: Warehouse/Vehicle Storage Building, Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site (The Jaeger Company, 2002)

Proposed Partnership for Development of the Tuskegee Airmen National Center: Report to the U.S. Congress (April 2002)

Special Resource Study: Moton Field/Tuskegee Airmen NHS (October 1998)

The Tuskegee Airmen Oral History Project and Oral History in the National Park Service (J. Todd Moye, excerpt from The Journal of American History, Vol. 89 No. 2, September 2002)

tuai/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025