|

TUMACACORI

Tumacacori's Yesterdays |

|

TUMACACORI AS A NATIONAL MONUMENT

When Tumacacori was proclaimed a national monument in 1908, the Forest Service was first responsible for it. They built a fence around the 10-acre tract, and occasionally inspected the area, but were unable to provide local care for the place.

On August 25, 1916, Congress established the National Park Service, which has since carried out the protection of Tumacacori mission and the interpretation of its history for the visitors. In 1921 some repair work was done to the church and the ruins of the other old buildings and walls to protect them against excessive weathering; a new roof was placed over the long nave, and lesser repairs were made to other portions. Repair work since that date has been limited almost entirely to preserving existing original construction. In other words, the National Park Service is seeking here not to restore the building to its original appearance, but to so stabilize it that it will not go into further ruin.

The modern visitor to Tumacacori National Monument arrives by paved U. S. Highway 89, 48 miles south of Tucson, 17 miles north of Nogales. From the roadside parking area he enters first the Spanish-Colonial type museum building. This structure houses a series of historical exhibits and some outstanding dioramas (three-dimensional exhibits in miniature) which combine to give the visitor a good cross section of mission history in this portion of the Southwest. Adjoining the museum has been developed a patio garden which is typical of the mission gardens of the Spanish period.

Visitors, after payment of a small guide fee, are accompanied by a National Park Service ranger as they leave the museum building for a guided walking trip through the mission church and grounds, a short distance to the north. There are a number of these guided trips each day, during every day of the year.

|

| Entrance of the Tumacacori Museum. (Harry Reed photo) |

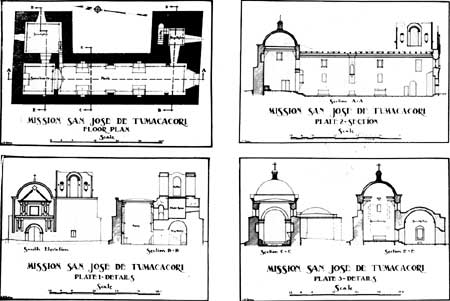

The church is a massive structure of adobe and brick (burned adobe) facing south. In plan it has the shape of a great capital letter E, minus the middle arm. The vertical part of the E is the long axis of the building, running north and south, extending from the entrance through the nave, into the sanctuary at the north end. The lower right arm of the E has the baptistry on the ground floor, a room for the choir at the second floor, and the bell arches at the third floor level. The upper right arm of the E is the sacristy.

|

| The pool and fountain in the patio garden of the museum. (Harry Reed Photo) |

Some of the interesting outside dimensions of the church are:

Greatest length: 101 feet.

Width across south end: 50 feet 7 inches.

Width across north end: 49 feet 9 inches.

Distance between the two "arms" of the E: 42 feet 2-1/2 inches.

Width of nave: 28 feet.

Ground level to top of unfinished bell arches: 39 feet 9 inches.

Ground level to top of lantern (domed colonnade on top of sanctuary dome): approximately 41 feet.

Some interesting inside dimensions are:

Greatest length: 89 feet 1 1/2 inches.

North-south length of entrance (narthex): 10 feet.

East-west: 17 feet 3 inches.

Length of nave: 54 feet. Width: 17 feet 3 inches.

North-south length of sanctuary: 17 feet 4 inches.

East-west: 17 feet 5 inches.

Baptistry, north-south: 9 feet 1 inch. East-west: 9 feet 6 inches.

Sacristy, north-south, 20 feet 1/2 inch. East-west: 16 feet 6 inches.

Ceiling height of nave: 23 feet 6 inches.

Ceiling height of sanctuary: about 32 feet.

The foundation of the building, running about five feet below original ground surface, is made mostly of great river boulders, set in mud mortar. Above this the walls range in base thickness from slightly over 9 feet in the baptistry to a minimum of 5 feet, with average base thickness, for all except the three-story section, of about 5 feet 6 inches. At about three-fifths of the distance from ground level to the nave roof occurs a reduction in wall thickness of about 2 feet, which extends around the west, north, and east sides of the building. Another similar offset occurs at the base of the bell arches, extending all the way around them.

|

| Mission San Jose de Tumacacori. |

At one spot in a lower portion of the wall we have a cross section visible, showing a building technique which presumably extends throughout the lower more massive walls of the structure. This reveals a core of rubble masonry, river boulders set in mud mortar. Sun-dried mud bricks (adobes), set in mud mortar, to a thickness of two rows, both on inside and outside of the wall, retain this core. Over the outer and inner wall surfaces were applied two heavy coats of lime (calcium carbonate) mortar, which is simply a mixture of fired lime and water (lime putty) and river sand. The walls above the offset probably also have a stone core, but it would have to be thinner than the core at the base.

Where greater strength was necessary, adobe bricks were burned by fire, and, where used, were set in lime mortar. These red, fired bricks were used for all wall capping, such as in the cornice around the top of the nave, for interior molding below the cornice, for the construction of the sanctuary dome and the sacristy barrel vault, and for the bell arches. Seen from above, the unfinished bell arches show a thin brick shell for a rubble masonry core. Fired brick was also used in other portions of wall construction, although in small areas, and in making the altars inside the building. In all probability, had there been an abundance of native labor available, the missionaries would have had the entire building made of the vastly more durable fired brick. But with labor at a premium, the builders had to be content, for the most part, with the less time-consuming adobes.

|

| Interior of the nave, looking toward the sanctuary, before the modern brick floor was installed. |

All interior plaster of the long axis of the church was coated with one or two brush-coat layers of gypsum plaster. Over this chalky white base was applied all the painted interior decorations. Since one decorated layer of gypsum wash occurs over a base layer, also decorated, it is clearly evident the church was redecorated once. The first decoration logically would have been completed not long before or after Father Liberos put the church into use, in 1822. We do not know when the second gypsum wash and its paintings were applied.

The original floor of the church, long since ripped up by treasure hunters, was a six- to eight-inch thickness of lime mortar and broken fragments of burned adobe brick. This had a well-smoothed upper surface, painted a deep red with ferric oxide pigment. In 1939 the National Park Service replaced the missing floor with one of mission-type fired brick.

Over the length of the entrance and nave was originally a timbered roof. Horizontal beams of Ponderosa Pine, roughly squared to about 6" by 6" cross section, rested on the inside cornice. These supported smaller material, probably a mat of Ocotillo stems or small tree branches. Above this we can also presume was a practically mortar-tight matting of grass or wheat stems, which in turn would have supported a several-inch thickness of lime mortar and brick fragments.

The original roof of the nave was gone by the end of 1849. This can reasonably be inferred from reports of travelers, quoted earlier in this narrative. The collapse probably occurred from neglect and resultant moisture at the timber ends, and termite action. The present roof over this portion is purely a utilitarian one, and not intended as a faithful copy of the original.

The baptistry, connected on its west side with the narthex by a 9-foot-long arched passage, has a large rectangular window in its south wall. This gives plenty of light to the room. In the old days there must have been heavy wooden shutters which could have been bolted from inside to protect the building from possible invasion by hostile Apaches through this opening. In the northeast corner of the room a passageway and steps lead through the north wall upward to the west, angles southward in the west wall, and angles eastward in the south wall as it rises to the base of the bell arches. An opening from this passage enters the west wall of the room for the choir, directly above the domed baptistry ceiling. This room received direct illumination solely from a slit in the east wall, a slit which tapered greatly to a very wide interior opening, to make maximum use of the tiny amount of light which entered.

|

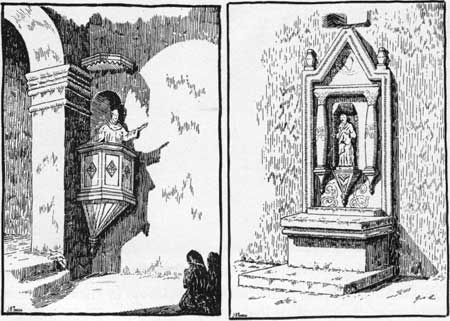

| Theoretical restorations of the pulpit, left, and a side altar, right. Drawings by J. H. Tovrea. |

Across the passage west from this room another opening led out into the choir loft. The loft extended across the south end of the long axis of the building, resting at the north end on an arch which separated the narthex from the nave. The loft long ago collapsed, probably when the nave roof fell in, and now only the arch bases remain. Light entered the loft from a large window in the south wall of the church, a window directly above the arched entry door. Four other large windows at the same height provided illumination through the east and west walls of the nave, and two others served similarly in the east and west walls of the sanctuary.

The north end of the nave is separated by a lofty archway from the sanctuary. The archway supports the south side of the dome. In the extreme northeast corner of the nave was the pulpit, entered by an arched passageway and stairs from the southwest corner of the sacristy. The original pulpit and stairs long ago were destroyed, and are now represented by partial restorations.

Along the east and west walls of the nave are the remnants of four side altars and their bases, all of fired brick and lime mortar. They are directly beneath the four high windows. Midway of the walls, between the side altars, facing each other across the room, are two ceiling-high pilasters, each with a small base at the bottom. These each contain two statue niches, one above the other, and probably served as shrines.

Above each of the side altars are statue niches, and around part of one is the remnant of an attached column which once formed a decorative framing for it. There is evidence that another column paralleled it, reaching a gabled point at the top, and that all the side altars had similar embellishment. There were undoubtedly statues of several saints in the various niches.

|

| Close-up view of the sanctuary. |

In the sanctuary the main altar of the church, against the north wall, was long ago destroyed. Tradition has it that the present partial reconstruction of the altar was done by Pedro Calistro, a very devout Opata Indian who lived nearby in the early part of the present century, and who for years constituted himself an unofficial caretaker for the building.

Above the altar is a roughly cross-shaped broken area in the plastered wall, and at first glance one always assumes the crucifix rested here. Closer examination, however, makes it fairly evident that to have fitted the present depressions, a crucifix would have had to be reversed. Therefore, it is more likely that (a) a statue, such as a figure of the Madonna, may have been attached here, or (b) that only a part of the cross-shape is from original structural insertion, and that possibly a brick canopy was attached to the wall here. In the latter case, the crucifix or figure of the Madonna could have stood or been fastened beneath. It should be borne in mind that, in any case, the cross need not necessarily have been fastened anywhere, but could have been portable and standing on the altar.

Above the questionable cross-shaped spot is a deep, ragged hole in the wall, where originally must have been a niche. It likely contained a statue of St. Joseph, the patron saint of Tumacacori in Franciscan times. There are masks to indicate that a reredos in partial relief was attached against the wall around the cross-shaped area, but we have no evidence as to its appearance.

To either side of the niche for St. Joseph, broken brick ends show where free-standing attached columns rose, to support a pediment. The pediment is now gone, but the outline shows it consisted of relief work in the shape of a gable, with the upper tip left out. Above this are two nicely executed, plaster relief, crossed palm fronds, the traditional Christian symbol of martyrdom. Above the fronds is a shelf-like plaster and brick corbel, which may have supported a tri-fold set of figures or pictures. Outlines of where these objects may have been attached to the high wall are still visible. They could have represented the Holy Trinity.

Framing the space for the reredos and crucifix and the niche for St. Joseph, are black and brown painted lines on the plaster. Several of these lines form a rather wide border, vertical on the sides, save for lateral partly rectangular extensions near the top. This framing is capped, on left and right, by two painted volutes in the same colors.

To the left and right of the painted framing are grooves in the wall which must once have contained pedestals. The pedestals in turn would have supported small statues, against a background of red curtains painted on the wall.

|

| Spanish items from Quiburi mission, Arizona: steel scissors, bronze thimbles and iron needle, left; restored Majolica dish, center; and bronze buckles, right. Courtesy, Charles DiPeso, Amerind Foundation. |

|

| Religious items from contemporary Quiburi: bronze candle-snuffer, left; bronze crucifixes, a Jesuit medallion, and a piece of book applique, center; and bronze candlestick, right. Courtesy Charles DiPeso, Amerind Foundation. |

Along the east and west walls of the sanctuary, just below window level, and on each side of the south arch, are a total of 12 rectangular outlines where once were fastened pictures, evidently of the 12 apostles. There are also several friezes of stencilled flower patterns across the east and west walls, and circling above the south arch, as well as many other small stencilled designs circling the base of the dome, and inside some compass-drawn circles in the extreme top of the dome. In the center of the arch, other compass-drawn circles have tiny free-hand designs painted inside them. Some free-hand scroll work is also visible in horizontal bands on either side of the arch.

The sanctuary is by far the most highly decorated part of the church, with remnants in several colors, of a number of designs. One of the pigments, a blue, is from the Indigo plant. It is doubtful if the missionaries made plantings of the Indigo here, probably bringing the pigments from more southernly areas where the plants were grown. All other colors are mineral, including the brilliant red of cinnabar, the yellow and orange of the ocherous hematites (iron oxides), the green of one of the copper compounds, and the black of carbon, presumably charcoal. With the exception of the charcoal, which was most likely locally made, we have no idea whether the missionaries had the other pigments ground from minerals obtained in this district, or brought them in from the south.

The vehicle, or carrier, for the pigments has long ago disintegrated, and disappeared, which has left the pigments very soft and powdery. Presumably the vehicle was a water-soluble vegetable base, such as Mesquite gum. In order to stabilize the pigments, and the soft gypsum wash on the plaster surfaces beneath, the National Park Service has sprayed all interior plaster and decorations with a vinyl acetate spray, which is invisible, and fixes the pigments after the manner of a pastel fixative.

|

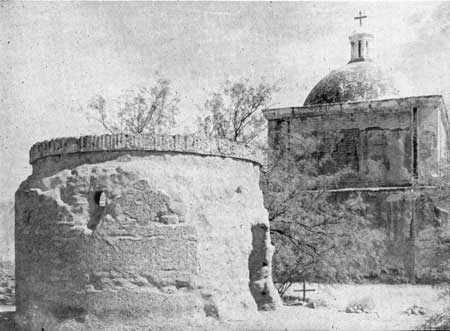

| The mortuary chapel in the cemetery, with adobe bricks coated with cement stabilization plaster. |

From the sanctuary a door opening leads east into the sacristy. On the sanctuary side this door opening has original pine headers, and on the sacristy side it changes to an adobe arch, covered in part with original lime plaster. The sacristy walls are of adobe, except for some fired brick near the top, and the barrel-vaulted ceiling is of fired brick and lime. The restored steps to the pulpit, in the southwest corner of the room, have already been referred to. On the east side of the room is an opening, arched on the interior, rectangular on the outside, which leads into what was once a corridor to the patio. On the north side of the room is a large window, which was long ago used so much that most of the lower part wore away, and it is now used as a door into the cemetery to the north.

In J. Ross Browne's description of the "corral" north of the church we have given location of the gates, and have mentioned that the west rooms of the patio formed part of the east wall. The cemetery wall was of adobe bricks, capped with fired bricks, and had the conventional two-coat lime plaster surface treatment. Fourteen deep oval niches regularly spaced around the wall once contained medallions to picture the Stations of the Cross.

The unfinished mortuary chapel occupies the south center of the rectangular enclosure. This building, evidently intended as a place in which to lay out the dead in preparation for burial, where the priest would likely have urged the Indians to have their wakes, is of adobe bricks, with fired brick cornice and molding, and had one plaster coat. Entrance was by means of an arched opening on the west side. In the north and south sides of this circular building, well above head height of a standing person, are two round holes, much larger on the inside than on the outside. These were presumably for light and ventilation.

The dome of the mortuary chapel was never built, nor was the second plaster coat applied. Many brick fragments were worked, without a pattern, into the base plaster, and must have been intended to give it a rough surface, so as to provide a good bond for the intended finish coat. The entire structure has suffered severely from weathering, with plaster peeling off and adobe washing away. The National Park Service has coated the weathered earthen surfaces with a cement-lime-sand mortar which follows the irregular contours, and keeps rain water from continuing its destructive action.

|

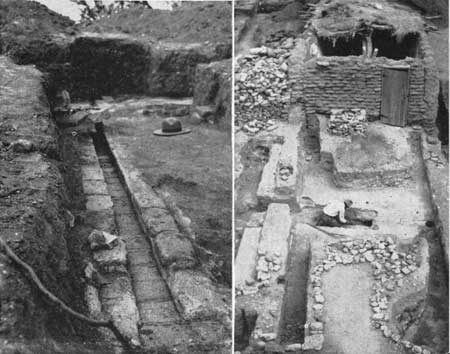

| The brick-lined ditch or drain, left, and a view of excavations of 1934 in Rooms 42 and 43, right. Note brick floor in lower right hole. (Paul Beaubien photo) |

It should be mentioned that a mortuary chapel was quite an unusual feature in Southwestern missions, although we know of one other, a rectangular one, at San Xavier.

The south wall of the cemetery, which is also the north exterior of the church, has two of the original water drains left, which run from the top of the building to ground level. These drains, of plaster, in cross section having the shape of a shallow arc, were painted a rich red with ferric oxide, and were highly decorative as well as utilitarian. Into the finish plaster surface of all the lower wall portion below the offset, here and on the east and west sides of the church, as well as all around the outside plaster surface of the cemetery wall, were worked handfuls of red and black brick fragments. These fragment clusters, placed in rows, horizontal, diagonal, and vertical, originally provided a beautiful contrast with the light colored lime plaster. Certainly the missionaries had ideas for beauty as well as utility, and were able to achieve it with minimum outlay of money.

Along the north and west exterior of the cemetery wall, as well as along the west side of the church, is a low brick, stone, and mortar retaining wall. This was doubtless to protect the plaster and earthen walls from the effects caused by rushing water when torrential summer rains hit the hills directly to the west of the establishment.

Although the missionaries made a considerable number of Christian Indian burials in the cemetery, none of the original markers remain. Long after the abandonment, cattlemen used the area as a roundup corral, and cattle must have done some damage. Later, treasure hunters destroyed any other original grave markers that remained, and dug up many graves. The grave markers visible today are from much later Mexican-American burials, coming down to as late as 1916.

Leaving the cemetery, one goes back into the sacristy, then eastward through a door into the corridor that led into the patio. Approximately 50 years ago a native family rebuilt missing parts of the corridor walls, constructed a wall across the open east end, roofed the chamber, and lived here. In the walls are built-in cupboards and windows made of boxes, which this family installed.

Entering the courtyard, the visitor sees that most of the wall structures have disintegrated into low mounds of earth. Of the rooms and arcades which went across the north, west, and south sides, only a small two-story remnant of the west side rooms adjoining the cemetery, and a short section of the south side rooms, remain standing today. On the east side of the rectangular enclosure was a wall, with no rooms. This wall has almost entirely dissolved.

In some of the courtrooms originally lived the one or two resident priests. Other rooms would have been for shops, granaries, storerooms, guest rooms, etc. Some rooms were undoubtedly used mainly for the Indian school, as the priests used to spend a great deal of time teaching the natives, not only how to become good Catholics and how to speak Spanish, but how to earn a living in any of several trades. Much of a missionary's success depended on how adequately he taught his converts to cope with Spanish civilization as it crept northward from Mexico.

East of the patio, in lower ground, was the great mission orchard, which extended over several acres. Nothing remains of the orchard now except part of the adobe and stone wall which surrounded it. Beyond and around the orchard undoubtedly were the fields, in the locations of modern fields of today.

|

| 1934 excavations in the rooms southwest of the church. The large tree is in Room 26. These rooms were part of the Indian town connected with Tumacacori mission. (Paul Beaubien photo) |

South of the patio and mission church, only a few feet away from the southeast corner of the latter, were two brick-and-lime-mortar tanks. These originally must have been water tanks, presumably fed by a small ditch coming in from higher ground to the west or south. On the west there is the possibility a large arroyo may have had a small regular flow of water which, dammed, would have ditch-fed the tanks. Or, a small ditch may have taken off from the main ditch some distance to the south to feed the tanks.

Although the connection is broken, there is good evidence that a brick-lined ditch flowed from the tanks, under the south rooms of the patio, into the west-central part of the enclosure, where must have been the patio garden. Fragments of a possible extension of this ditch may have led to a kitchen in the northwest corner of the patio, also.

Mounds, only partially excavated, indicate that the houses of the Indian town (the houses which were used while the present church was still active, with a resident priest) extended around a large rectangular plaza to the south of the church. We believe complete excavation would reveal that these adobe houses, or at least a compound wall of which they were a part, formed a closed area, connected at the northeast side with the patio walls, and at the northwest side with a wall which projected westward from the south face of the church itself.

The main ditch for the mission came from the Santa Cruz River. At its nearest point, the bed of the river comes within about half a mile of the church, to the east. However, to insure gravity flow of water where needed, the ditch came out of the river nearly a mile south of Tumacacori. It carried water as late as 1938, but stopped in that year, largely as the result of modern farmers putting in more and more wells. Pumping from these wells lowered the water table so greatly that now the Santa Cruz does not run in this portion of its course except during flood times after heavy summer rains.

Our description of Tumacacori would be incomplete without reference to structures that lie in the patio area east of the church. Late in 1934 an FERA project, under direction of Archeologist Paul Beaubien, was initiated for the purpose of extensive exploratory trenching, to locate and map historic structures in the vicinity of the mission church which are no longer visible on the surface. During the next several months a large part of this work project involved locating all wall and floor remnants of the old patio. This activity revealed that under some of the walls are remnants of older walls.

Less than 100 feet east of the present church building, underlying part of the patio garden area, are the stone wall foundations of what we believe was its predecessor. By this we mean the church which succeeded the adobe house chapel of Kino's time; the church in which Lorenzo, the alcalde, was buried in 1757; the one which Father Font located in his 1777 map on the east side of the river; the one which in 1795 was "a very cramped and flimsy little chapel, which has been made over piece-meal; and today it is big enough to hold the people of the Pueblo; it is made of earth and is in bad shape . . ."

This structure (Rm. 50, see ground floor plan, pp. 48-9), running east and west, facing east, had a total length of 59-1/2 feet. The east part was 50 feet long and 15 feet wide, and would have been the nave, somewhat smaller and more cramped than the nave of the present church, which is 54 feet long by 17 feet 3 inches wide. The west part, 9-1/2 feet deep by 8 feet wide, is a much constricted part of the foundation, and would have supported the sanctuary walls. This definitely was "very cramped" by comparison with the present sanctuary, which is over 17 feet across, each way.

We quote Beaubien's report on this discovery: "Possibly these foundations mark the site of an early mission. Facts in support of this belief are: the large size; appropriate proportion of length to width; foundation stones correctly placed to support the pilasters of a choir loft; the absence of any knowledge of other foundations which might locate one of the early missions supposed to be at Tumacacori; and, stone foundations high enough to carry plaster, unlike any other building on [the] monument except the present mission. The constricted sanctuary is not uncommon in early Southwestern missions."

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

jackson/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 10-Apr-2007