|

TUMACACORI

Tumacacori's Yesterdays |

|

INTRODUCTION

On U. S. Highway 89, a scant 18 miles north of the Mexican border, lies one of America's most historic landmarks, the mission church of San Jose de Tumacacori (tooma-COCK-oree). At this picturesque spot in the fertile Santa Cruz Valley, Christianity was ushered into what is now southern Arizona.

Over two and a half centuries ago, indomitable missionary priests brought a new religious concept into one of the most hostile Indian frontiers of this hemisphere. This concept took root, struggled for growth, and flowered after more than a hundred years in the paradox of an Indian-built edifice to the new God.

|

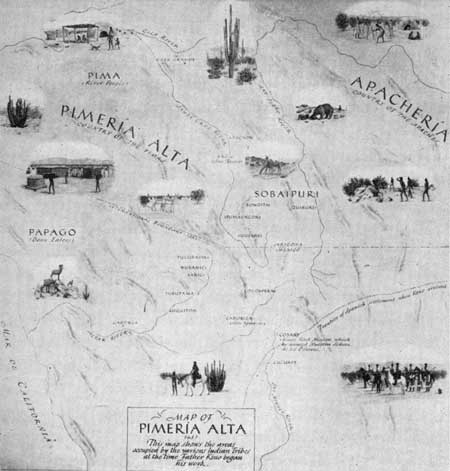

| Map of Pimeria Alta |

This structure was built of the timeless earth itself, and its walls have endured the ravages of age and vandalism to see the flags of four governments wave over the land.

To understand mission development, as it is illustrated here, it is necessary to have a quick look at Spanish colonial policy. In the late 17th century Spain was one of the world's great colonial powers, claiming territory far north of the present Mexico. In defense of her far-flung empire she dotted her frontiers with presidios, garrisons for the soldiers who maintained dominance over adjacent territory and kept the Spanish flag flying as a warning to possible aggressor nations.

It is apparent that if you spread a sand pile over a large enough area you eventually reach the point where the scattered grains lose their identity and merge with the soil, leaving it essentially as it was before. Spain had so spread her available military manpower that the capacity of her soldiers alone to hold territory against insurgents or invaders would have been inadequate.

|

| Tumacacori in 1944 before the columns and bases were restored. (Harry Reed photo) |

By masterful strategy, she spread her grains of sand very thin, but in such a way that instead of losing by the merger, they grew stronger. While the soldiers established presidios in the vicinity of Indian towns, their small forces, unaided, could not long have held supremacy over the vastly more numerous natives. So, shoulder to shoulder with the military commander, came the missionary priest to carry the Cross. It was his responsibility to convert the Indians to Catholicism, the state religion, and to establish a mission.

On the one hand the soldiers, as they sought to maintain military control and peace in their districts, were encouraged to fraternize and intermarry with the Indians, and to settle in the neighborhood of presidios. On the other hand the missionaries, in the dual role of apostles of the Church and envoys of the Crown, were expected as priests to convert and educate the natives, and as civil administrators to make them a part of "civilized" society.

|

| The facade in 1946 after restoration to protect the original columns. (Stan Davis photo) |

These tactics, although occasionally suffering reverses, were on the whole brilliantly successful. Friendships thus established secured from many native groups a loyalty which was far more potent than guns in holding frontier control. The desire of the Church to save souls dovetailed perfectly with the more mundane desires of the State. This colonial policy so thoroughly implanted Spanish language, religion, law, and social custom in New Spain that it profoundly affected the course of history.

|

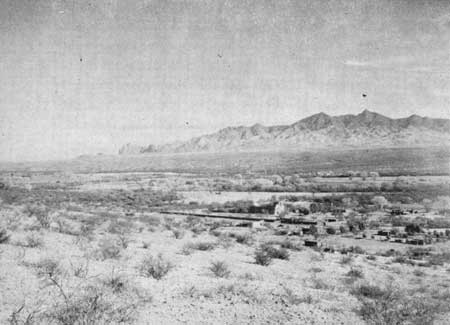

| The valley of the Santa Cruz River at Tumacacori as it appeared in 1934. The Santa Rita Mountains in background. (C. P. Russell photo) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

jackson/intro.htm

Last Updated: 10-Apr-2007