100 Years of Federal Forestry

Agriculture Information Bulletin No. 402

|

|

|

|

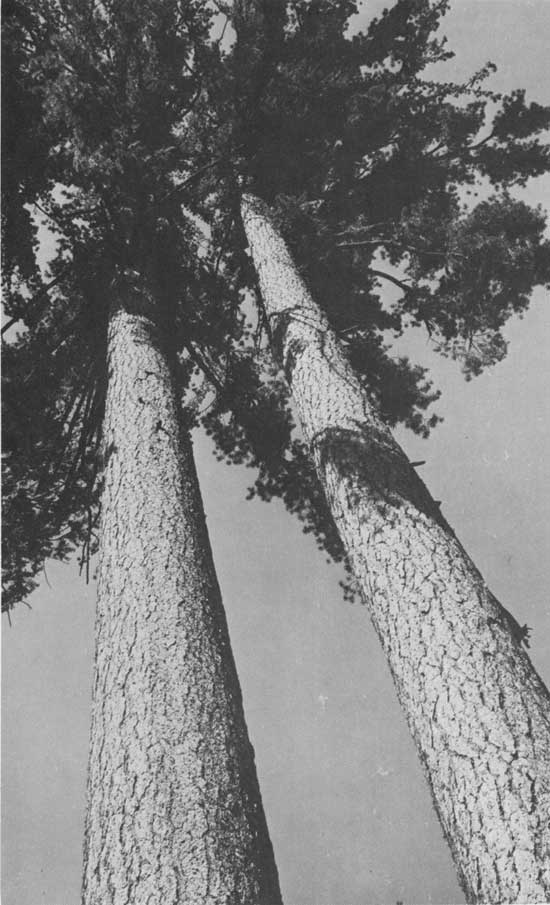

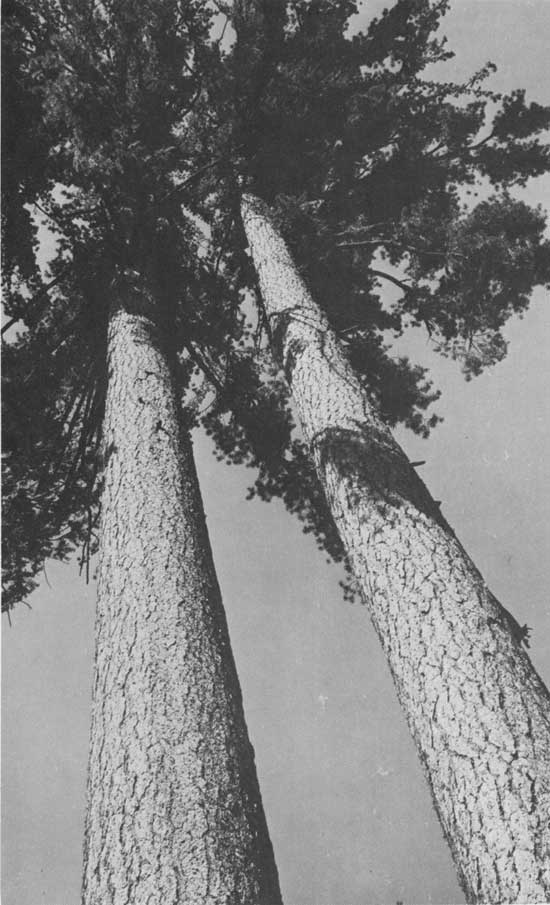

1. Sugar pines, Sequoia National Forest, California. (F—504980)

|

Keeping Up With The Times, 1961-1975

Highlights

On July 1, 1876, the population of the United States,

as then constituted, was roughly 46.1 million.* On July 1, 1975, our

population was estimated by the Census Bureau to be 213.5 million,

including the Armed Forces overseas. With this increase of 167.4 million

men, women, and children in 100 years, and with our natural resources

less abundant than a century earlier, there was need to stretch these

resources, especially the forests, to their greatest possible, practical

use. To accommodate the demands of the ever-growing population (there

were 34.7 million more people in the country in 1975 than in 1961), the

National Forest System was called upon to yield more wood, more water,

more recreation, more range forage, and more wildlife habitat than ever

before. Other Federal outdoor areas and the privately owned forests also

felt the pinch.

*Historical Statistics of the United States

(U.S. Department of Commerce).

As a consequence, the period from 1961 to 1975 was

one of greater challenges for the Forest Service than it had faced

before. A change of direction was needed to meet the needs of the new

era efficiently and effectively. This changeover was characterized by a

gradually quickening shift from short-term management concepts to fully

planned, longer range management. This conscious effort to keep up with

the time brought notable advances.

The Forest Service instituted the principles of the

Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act (1960) throughout the National Forest

System. The purpose of the Act was to insure that all possible use and

benefit might be extracted from the public forests and grasslands

without endangering their future usefulness and productivity.

The activities of Forestry Research and State and

Private Forestry intensified, and emphasis on the use of

interdisciplinary teams increased. These teams represented a wide range

of specialities, for example, wildlife biologists, landscape

architects, soil scientists, range experts, engineers, and foresters.

The teams began working to meet current demands on the Forest Service

and to prepare plans designed to better mesh human needs with a

sustained supply of natural resources for the future.

The Nation became more conscious of its environment,

in a spirit akin to but more refined than that of the first decade of

the 20th century. There was a new appreciation of environmental values

and of the need to protect them, achieving expression in the National

Environmental Policy Act of 1969, which profoundly influenced Forest

Service planning and programs. In response to the heightened public

awareness of federal activities, the Service launched a program in the

early 1970's to "inform and involve" the people in the decisionmaking

process as it affected their interests in the forests. The goal was

meaningful public involvement in developing better land and resource

management.

The most ambitious planning initiative of the Forest

Service involved 3 years of extensive effort culminating, in mid-1974,

with "A Long Term Forestry Plan (Draft)—Environmental Program for

the Future." This was a comprehensive plan involving the National Forest

System, Research, and State and Private Forestry. The Forest and

Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act (PL 93—378) of August

1974 coincided with the Environmental Program for the Future and was one

of the most significant Congressional conservation actions in many years

to have so great an impact on the future of American forestry. This Act

represented the first legislative recognition by Congress that

management of our natural resources can be fully efficient only when

planning and funding are done on a long-range basis, not

year-to-year.

The Resources Planning Act covered all Forest Service

areas of responsibilities and activities—the research and

cooperative programs and National Forest System management. It required

periodic analyses of present and anticipated uses, demands for, and

supply of renewable resources. The international resources situation

also had to be incorporated. The Act required that the first national

assessment and program be submitted to Congress by the end of 1975. In

complying, the Forest Service was able to draw on its own Environmental

Program for the Future for pertinent material on outdoor recreation and

wilderness, wildlife and fish habitat, rangeland grazing, timber, land

and water, and human and community development. The experience of the

first century of federal forestry thus in a blueprint for the next

century.

1961-1975

|

|

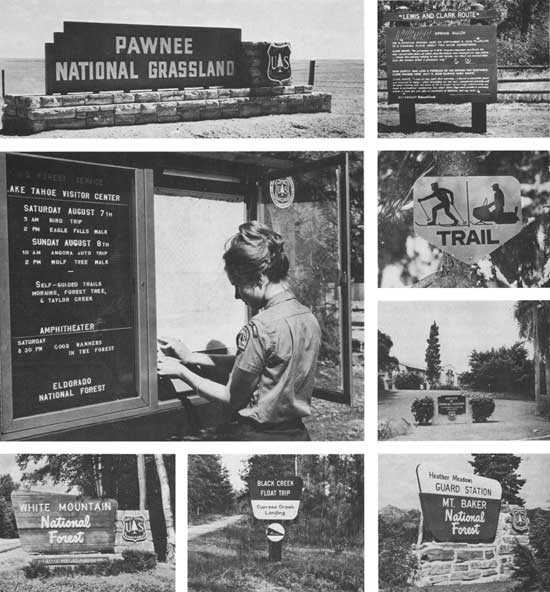

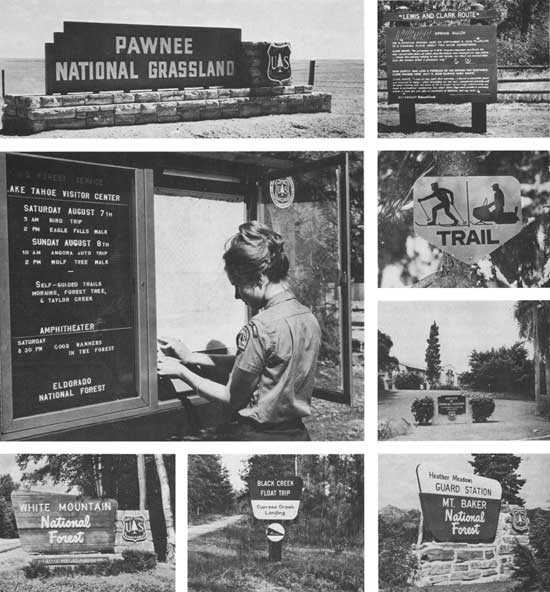

Signs— 1 (top left). Colorado. (F—503670) 2 (middle left). California. (F—513408)

3 (bottom left). New Hampshire. (F—515783) 4 (bottom center). Mississippi. (F—515920) 5 (top right).

Montana. (F—515566) 6 (2nd from top right). Oregon. (F—519209) 7 (2nd from bottom right). Puerto Rico. (F—522904)

8 (bottom right). Washington. (F—514484)

|

|

|

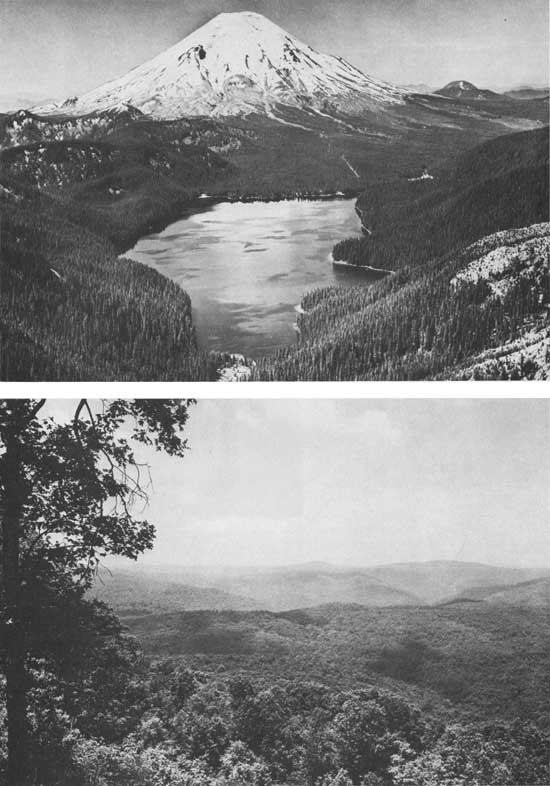

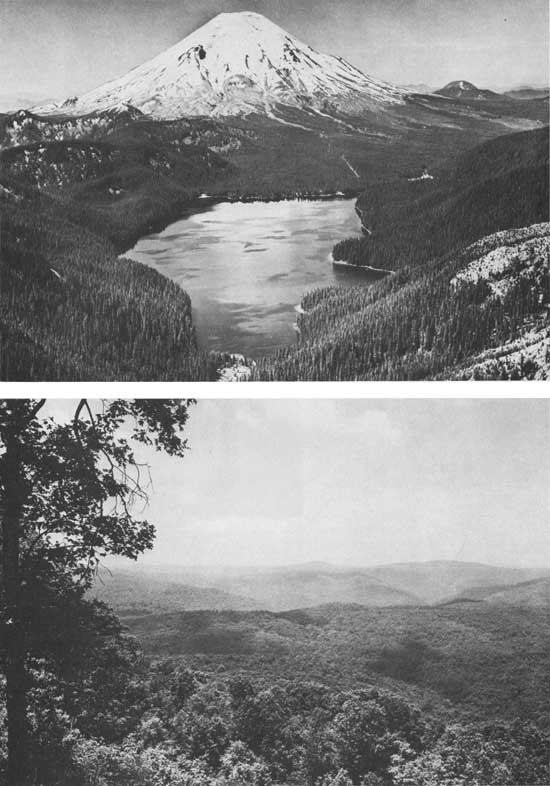

1 (top). Water for a hundred purposes . . . (Gifford Pinchot National

Forest, Washington). (F—516462) 2 (bottom). Wood for a thousand uses . . . (Ozark National Forest,

Arkansas). (F—504877)

|

Sidelights (1961-1975)

During this period an interesting trend began to

develop, a trend with favorable portents for American forest

conservation and for the Forest Service of the future. There was a

special accent on youth through the Job Corps and the Youth Conservation

Corps, a new emphasis on State and Private Assistance through forestry

incentive programs, an introduction of modern techniques in forest

management and forestry research, and an offering of new services and

opportunities for all Americans—a general upgrading of both

environmental and human resources.

The Job Corps program, starting in 1965, gave young

men from deprived backgrounds basic schooling, training in skills, and

valuable job experience.

The Youth Conservation Corps was launched in 1971 as

a 3-year pilot program featuring summer conservation work-learn

activities for young men and women from all parts of the Nation and from

all walks of life. The Corps was continued beyond 1974 as a permanent

entity because of its success in providing gainful employment, in

accomplishing needed conservation work, and in arousing its youthful

participants to a new understanding and appreciation of their Nation's

environment and heritage. By 1975, State-operated projects on

non-federal public lands were in full swing along with projects being

carried on in National Forests, National Parks, Wildlife Refuges, and on

other public lands and waters.

In 1971, new survey techniques came into being as

satellite photos and imagery were used to make a sample survey of 12

million acres of forests in the Southeast.

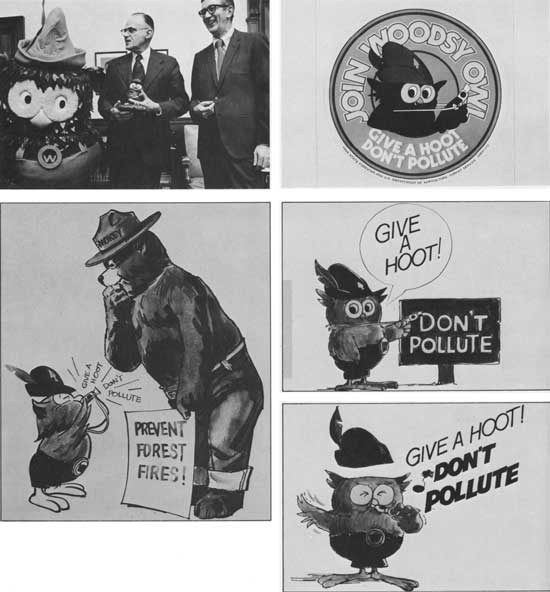

Also, in 1971, Smokey Bear was joined by a new

comrade, Woodsy Owl, a symbol for wise use of the environment that

quickly captured the attention and cooperation of millions of

outdoor-loving Americans. The Woodsy Owl symbol and slogan, "Give a

Hoot, Don't Pollute," are authorized and protected by law, just as

Smokey Bear is.

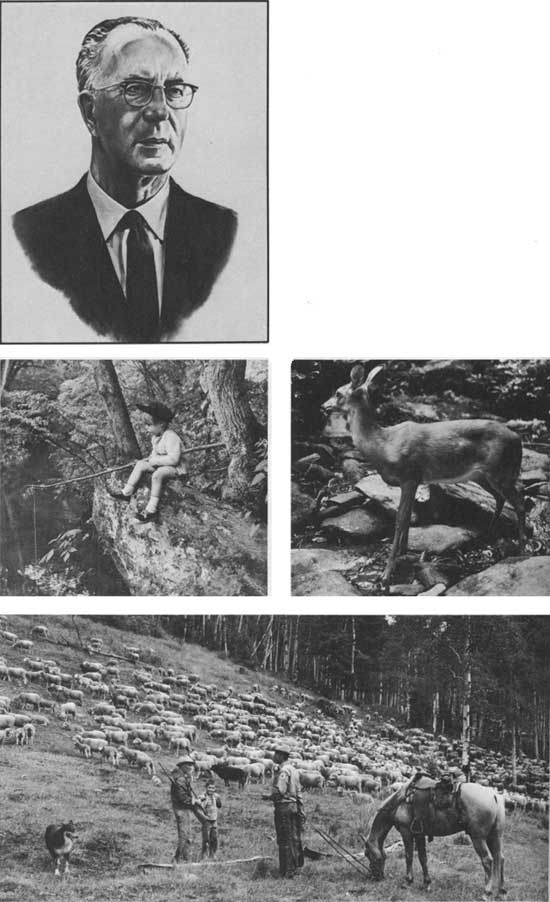

"As the population of the country rises and demands

on the timber, forage, water, wildlife, and recreation resources

increase, the National Forests more and more provide for the material

needs of the individual, and the economy of the towns and States, and

contribute to the Nation's strength and well-being. Thus the National

Forests serve the people."

Edward P. Cliff (1962-1972)

|

|

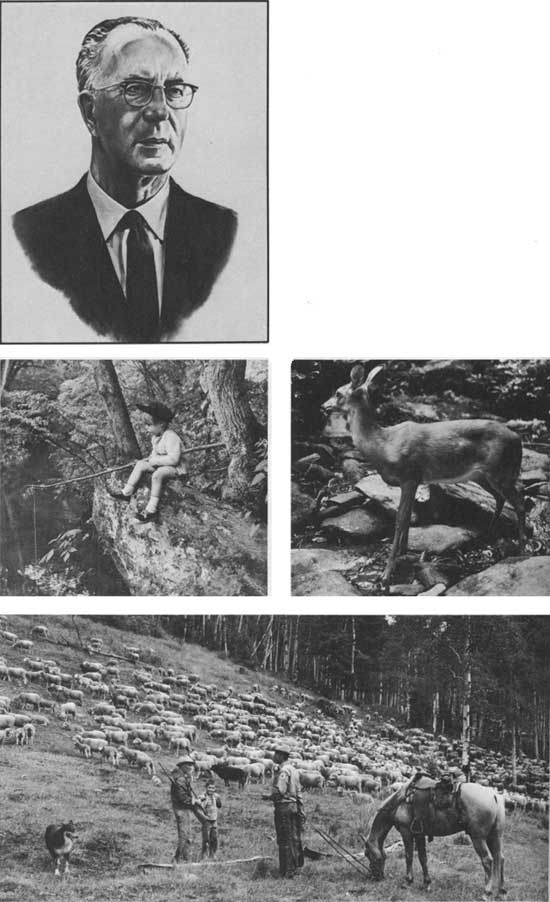

1 (top left). Edward P. Cliff, Chief of the Forest Service, 1962-1972. (Drawing by Rudolph Wendelin)

Domestic stock and wildlife . . . 2 (middle left). Fish. George Washington National Forest,

Virginia. (F—514850) 3 (middle right). Deer. Nantahala National Forest, North

Carolina. (F—494694) 4 (bottom). Sheep. Carson National Forest, New Mexico. (Forest Service,

Region 3, Carson National Forest)

|

1961-1975

In 1974, the Golden Anniversary of a priceless concept was observed

when the Gila Wilderness Area in the Gila National Forest, New Mexico, marked its

50th birthday. (Ten years earlier, in passing the Wilderness Act, Congress had

legally endorsed a long-standing Forest Service policy of establishing and maintaining

wilderness areas.)

The 50th anniversary of the Clark-McNary Act

was also observed in 1974, reflecting a dramatic evolution of State and Private Forestry

through the years, with ever-closer ties between the States and the Forest Service for the

good of the public and the forest resources.

|

|

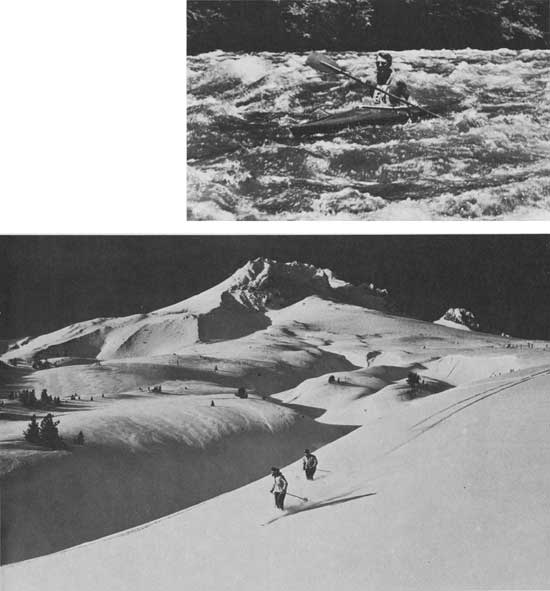

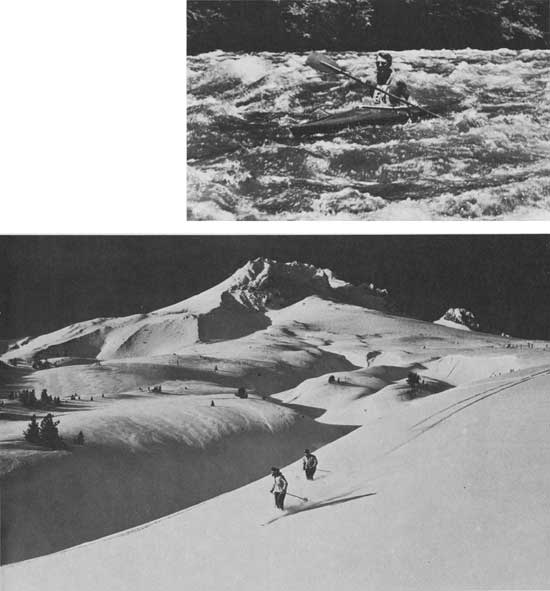

Recreation to fit every taste . . . 1 (top). Whitewater Championship

Canoe Races, Feather River, Plumas National Forest, California (1970). (F—519847) 2 (bottom).

Skiing, Mount Hood National Forest, Oregon. (F—499444)

|

|

|

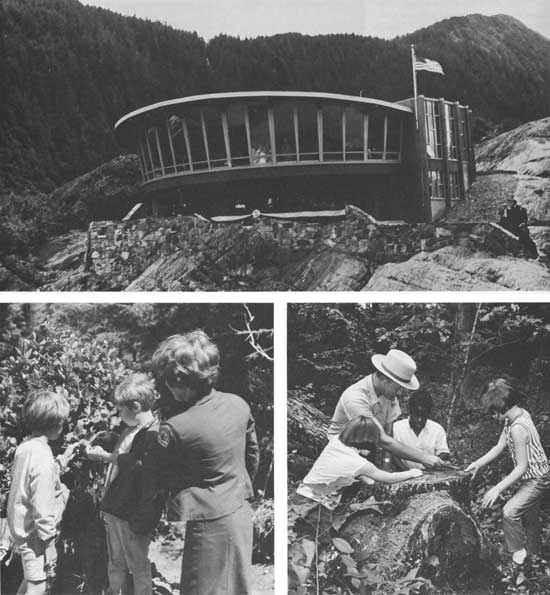

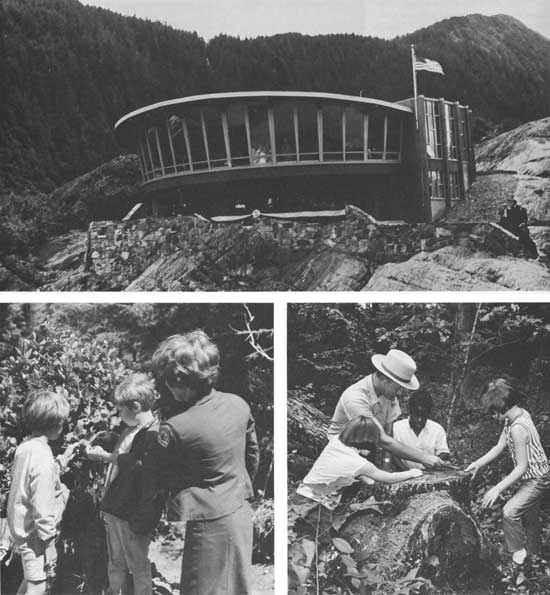

The Visitor Information Service of the Forest Service—specially

trained men and women and special facilities to further one's knowledge, to add zest to

the outdoor adventure, to enhance the visitors' enjoyment. 1 (top). Far North, in the Tongass

National Forest in Alaska, the Visitor Information Center makes viewing of the

Mendenhall Glacier a safer and more informative adventure. (F—518534) 2 (bottom left). The Cape

Perpetua Visitor Information Center on the Pacific Ocean captures the interest of young

plant examiners (Siuslaw National Forest, Oregon). (F—516687) 3 (bottom right). The annual growth

rings tell the age of a tree—the fast-growing years and the slow ones, the dry years

and the wet ones, and, quite often, there are marks of fires that had run wild through the

forest (George Washington National Forest, Virginia). (F—518780)

|

|

|

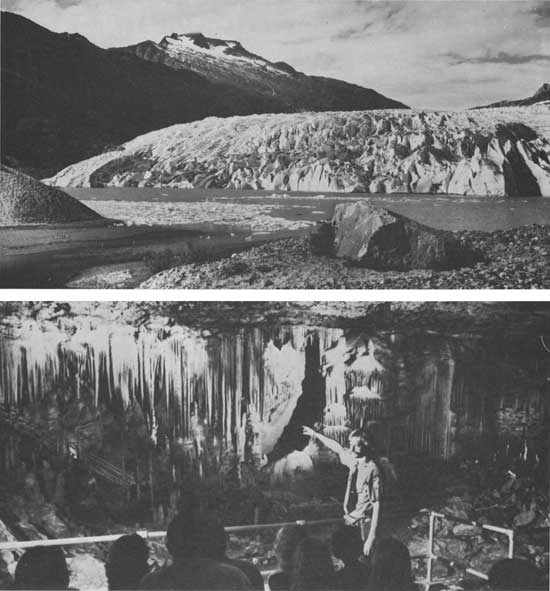

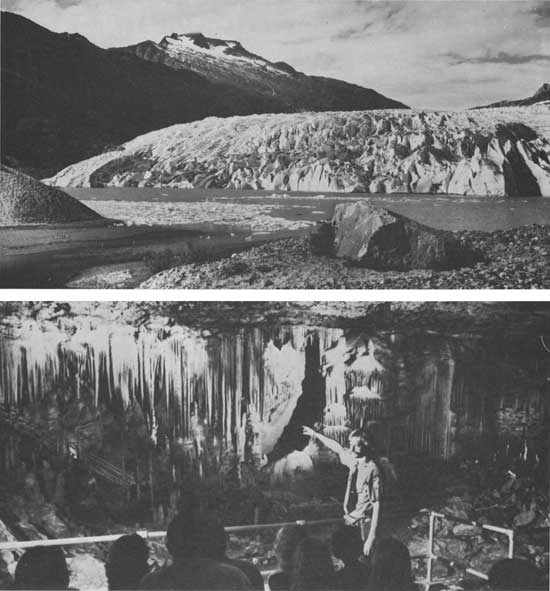

1 (top). Face of Mendenhall Glacier across Mendenhall Lake. (F—486789)

2 (bottom). A geological treat—Blanchard Springs Cavern in the Ozark National

Forest, Arkansas. (F—512984)

|

|

|

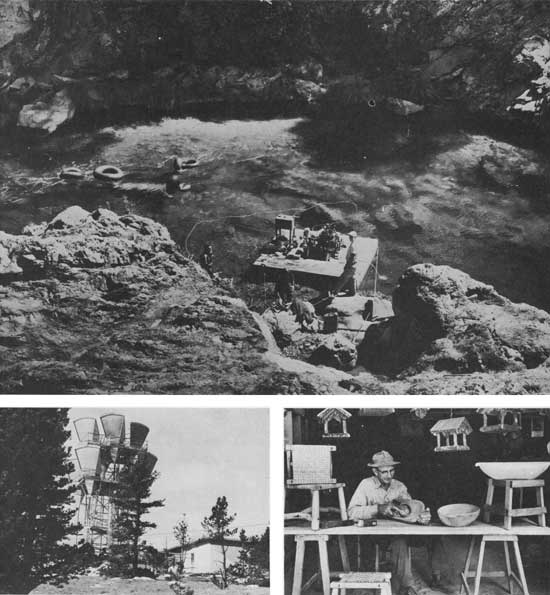

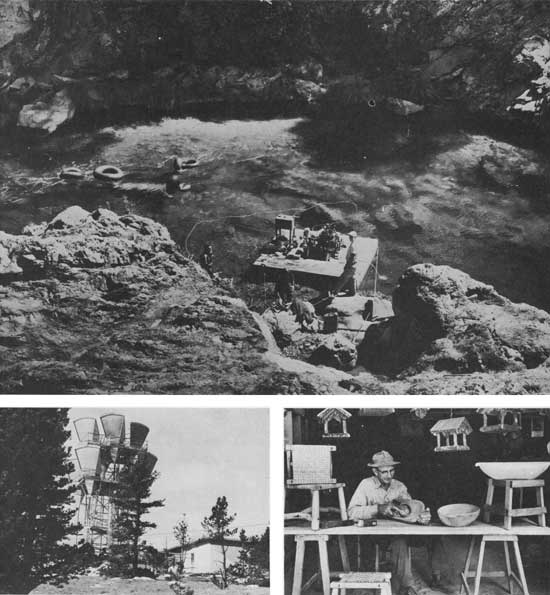

The Forest— 1 (top). There's gold in the river. In 1962, scuba divers

"vacuumed" the precious metal from the bottom of the North Yuba River in the Tahoe National

Forest, California. (F—503106) 2 (bottom left). A microwave station built in the early 1960's made this part

of the Helena National Forest, Montana, a high-value special-use area. (F—502316) 3 (bottom right). From farm

forests in North Carolina come the raw materials for hand-crafted wooden creations that have kept

many mountain and other rural residents profitably employed. (F—502169)

|

|

|

1. In Virginia these baskets are woven from oak splits and are

popular with tourists. The raw material comes from white oak from nearby farm forests.(F—508221)

|

|

|

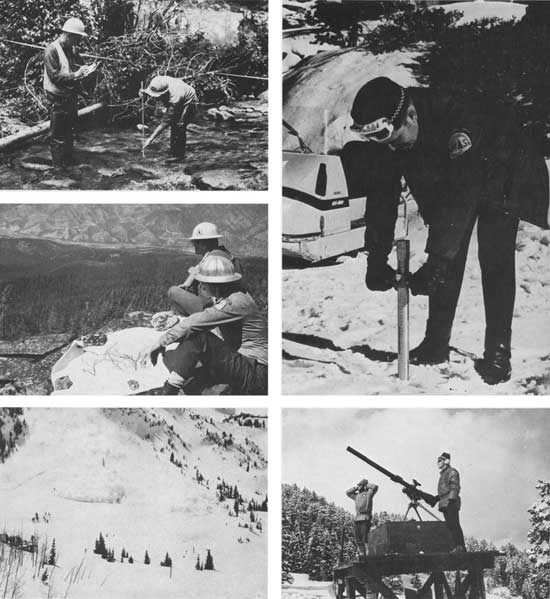

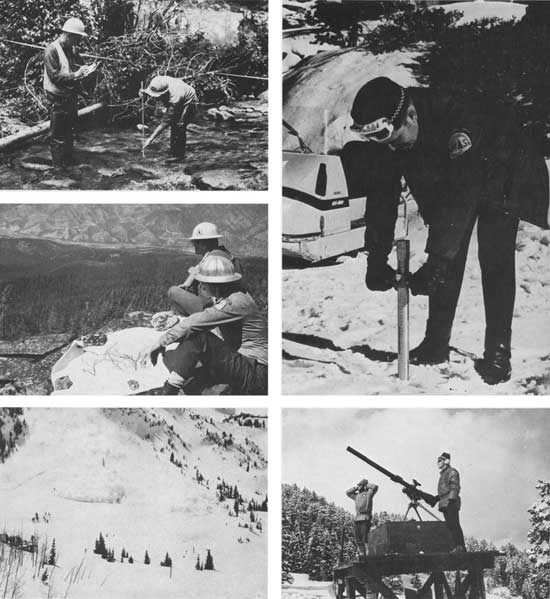

"All in the day's work . . ." 1 (top left). Stream habitat surveys indicate

quality of the aquatic environment and provide basic management data (Bitterroot National

Forest, Idaho, 1967). (F—519357) 2 (middle left). Checking terrain for suitability for skiing (Lolo National

Forest, Montana, 1966). (F—515020) 3 (bottom left). Avalanches can travel up to 100 miles per hour, and

carry well over 100,000 tons of snow and debris. Anything in the path of a large avalanche

is usually totally destroyed. The Forest Service supervises avalanche control activities at

developed ski areas with the objective of reducing the hazard to life and property (Wasatch

National Forest, Utah). (F—462494) 4 (top right). Measuring snow depth in February to determine summer

run-off possibilities (Tahoe National Forest, California, 1970). (F—520149) 5 (bottom right). Controlling

snow avalanches with 75mm recoilless rifle fire (Gallatin National Forest, Montana, April

1970). (F—520642)

|

|

|

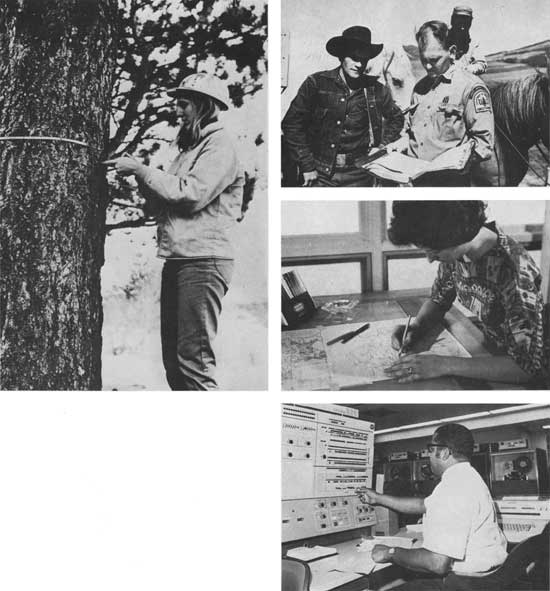

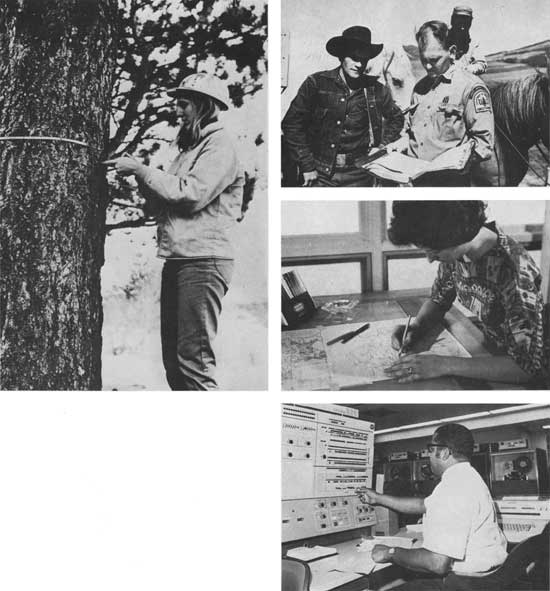

1 (top left). In the summer of 1965, a forestry technician on the

Lewis and Clark National Forest in Montana measured the diameter of a tree to

determine the volume of wood in it; (F—521722) 2 (top right). The District Forest Ranger checked

the range allotment map with a ranch foreman, the two men discussing details of the

grazing permit agreement, on the Routt National Forest, Colorado. (F—512720) 3 (middle right).

Meanwhile, back at a district ranger office in the Beaverhead National Forest, Montana,

the District Clerk prepared a similar range allotment map; (F—504545) 4 (bottom right). And, in

the Chief's headquarters in the Nation's Capital, another technician kept busy in the

Automatic Data Processing Center. (F—519994)

|

|

|

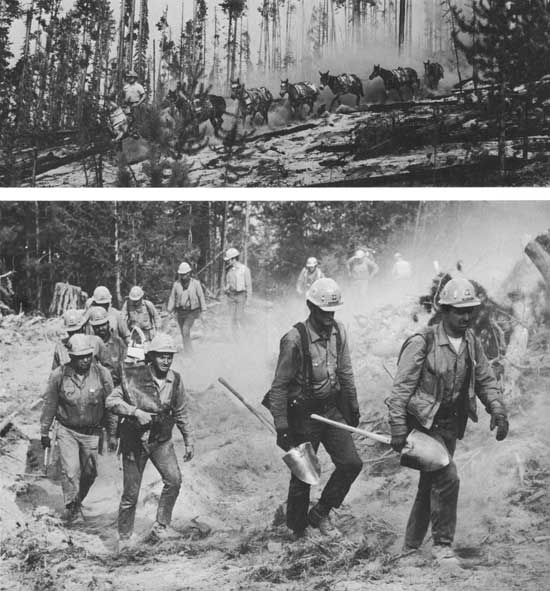

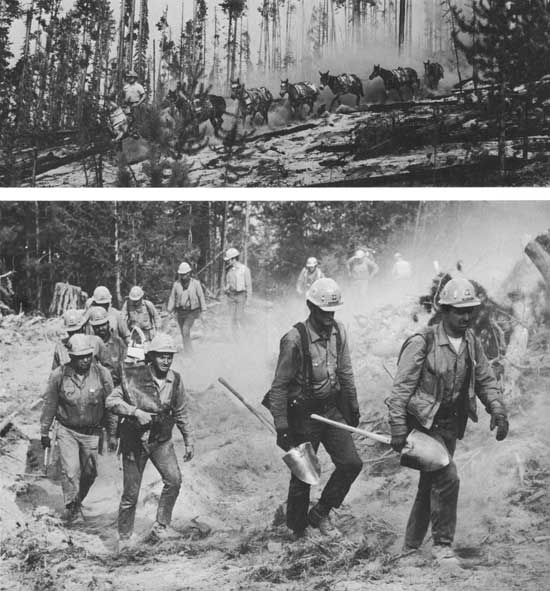

Protecting the forests—a never-ending responsibility.

1 (top). August 1961—1,650 men in 16 camps worked to control the

Sleeping Child Fire in the Bitterroot National Forest, Montana. Pack strings

helped supply fire camps that were inaccessible by road. (F—507314) 2 (bottom). August

1970—fire struck heavily on the Wenatchee National Forest in Washington.

Men moved up to the fire on foot. (F—520885)

|

|

|

1 (top left). Men also moved up to the 1970 Wenatchee Fire in

helicopters. (F—520902) 2 (top right). Water helped douse small spotfires . . . (F—520897) 3 (bottom). And

retardant was dropped from airtankers to slow down the fire's spread. (F—520868)

|

|

|

1. A different kind of spraying job took place on the Mt. Baker

National Forest in Washington during the summer of 1968—spraying with an

insecticide to control the ravages of the Hemlock Looper. (F—519176)

|

|

|

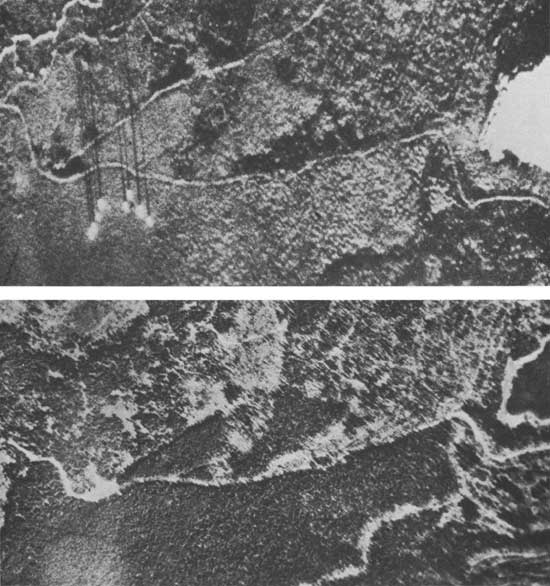

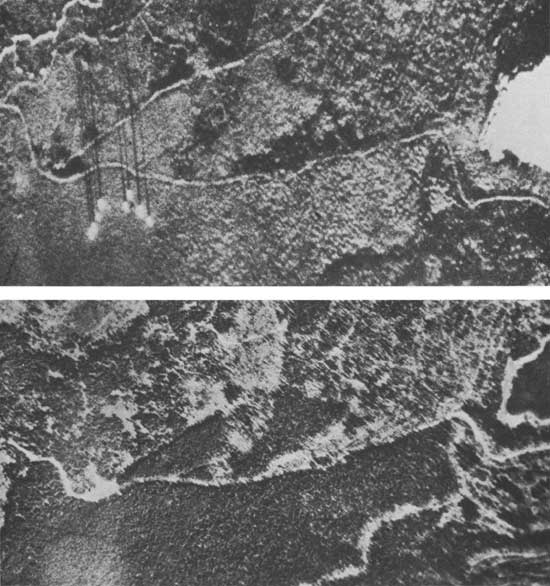

1 (top). Infrared photography became a valuable Forest Service

aid in the 1960's. The eight white lights (from eight small smudge pots) in

the lower left-hand corner were photographed using infrared imagery. (F—518607) 2 (bottom).

In this photograph, made with standard camera and film, the smudge pots do not

show up. Use of infrared photography makes it possible to locate fires while

they are still small, before they reach a dangerous stage. (F—518608)

|

|

|

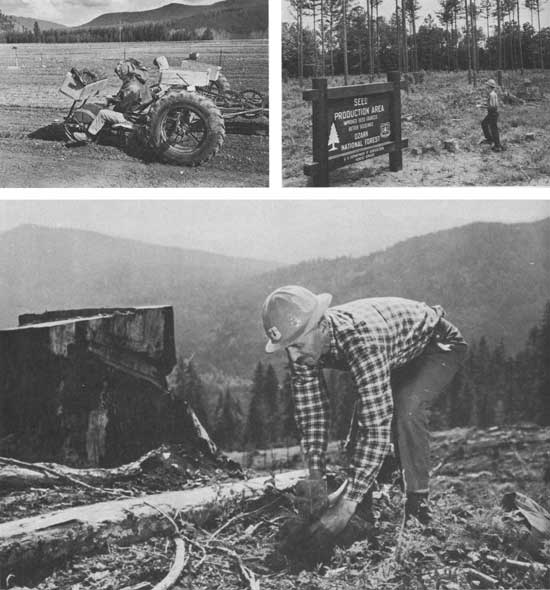

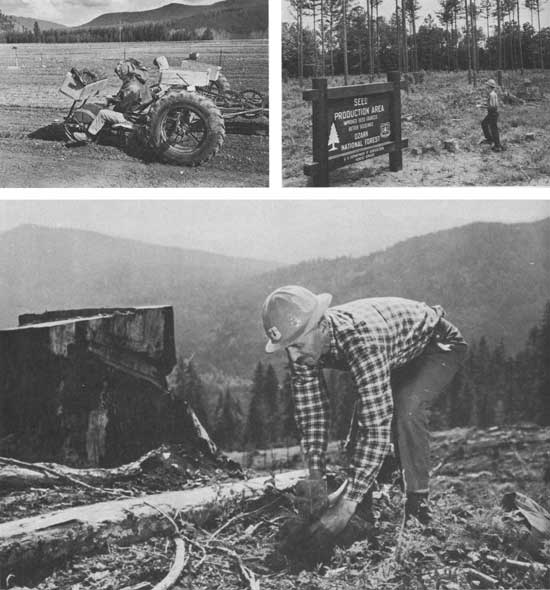

Planting for the future . . . 1 (top left). Transplanting 2-year-old

ponderosa pine seedlings in Savenac Nursery, Coeur d' Alene National Forest, Idaho

(1963). (F—504419) 2 (top right). Checking the seed production area on the Ozark National

Forest, Arkansas (1963). (F—505693) 3 (bottom). Tree planter at work in a clear cut area,

Gifford Pinchot National Forest, Washington (1965). (F—521178)

|

|

|

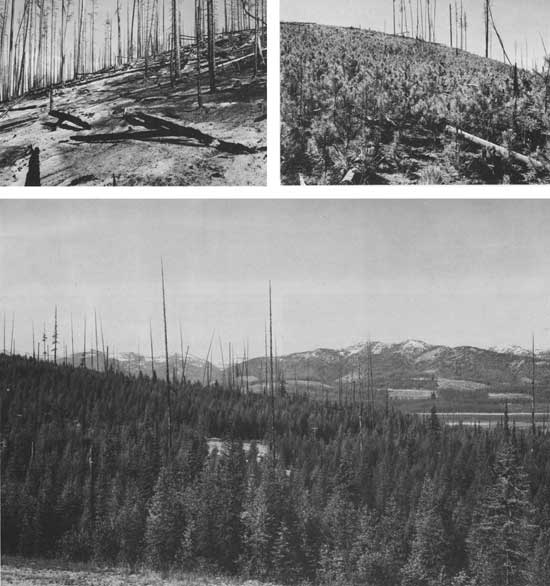

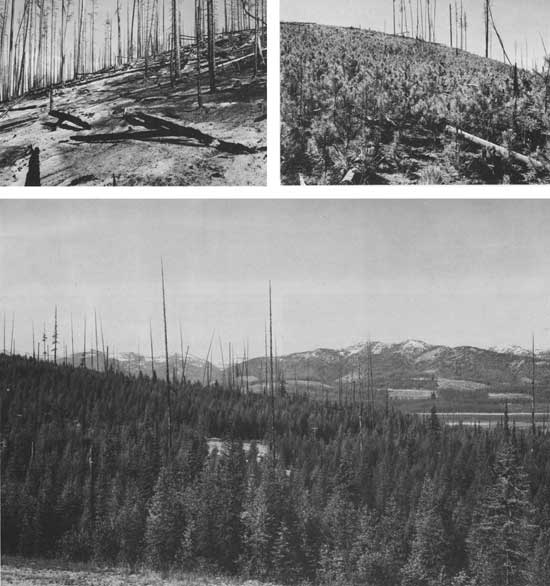

1 (top left). The aftermath of the Sleeping Child Fire, Bitterroot

National Forest, Montana, 1961. (F—522310) 2 (top right). Ten years after the Sleeping Child

Fire, the forest stages a comeback (Bitterroot National Forest, Montana, 1971). (F—522309)

3 (bottom). Stand of western larch reclaim an area damaged by a forest fire

(Flathead National Forest, Montana, 1967). (F—522055)

|

|

|

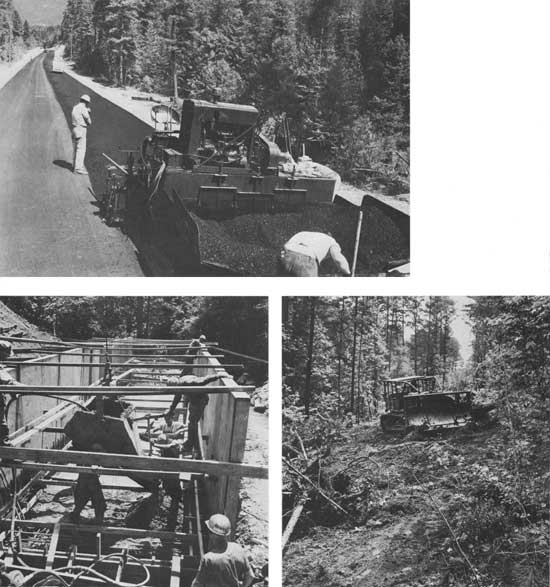

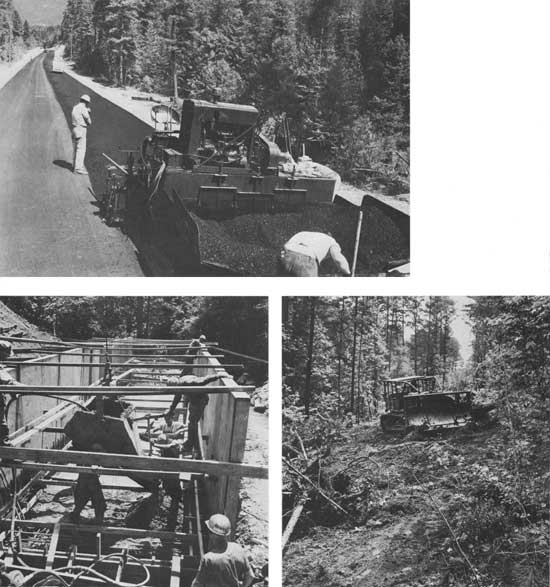

Road building—a major activity . . . As tools became more

sophisticated and techniques more modern, the Forest Service engineer began to

build his roads following straighter, safer, and faster routes. He gentled

the dangerous curves, bridge rivers, and bored through mountains. More speed

and more efficiency have become important as demands for wood, for recreational

outlets, and forest mobility have grown. The necessity has remained, however,

to maintain the beauty and integrity of the environment. In addition to building

roads and trails within the National Forest System, Forest Service engineers,

landscape architects, and other specialists also are responsible for the planning,

location, and operation of dams, buildings, power lines, water and sewer systems,

ski lifts, and generating plants—for management purposes, public use, or,

under permits, for commercial use. 1 (top). Kootenai National Forest. (F—506136) 2 (bottom

left). Sumter National Forest, South Carolina. (F—516310) 3 (bottom right). Talladega National

Forest, Alabama. (F—505732)

|

|

|

1. The Forest Products Laboratory at Madison, Wisconsin, is the

headquarters for the Federal Government's wood utilization research activities.

Through the years, FPL has proved to be a boon to government and industry alike,

with tremendous benefit to the public. (F—405515)

|

|

|

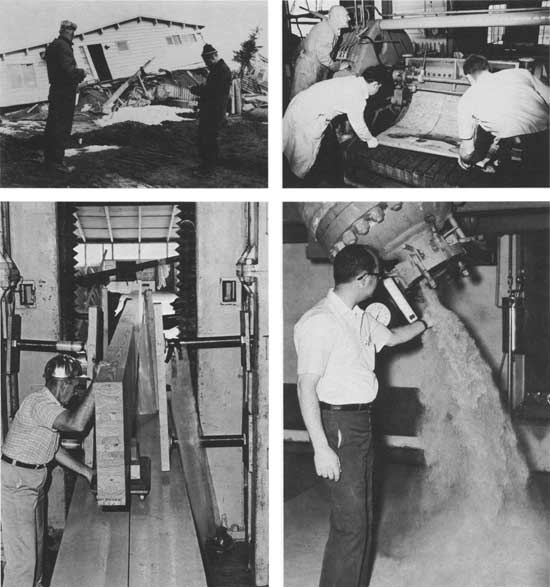

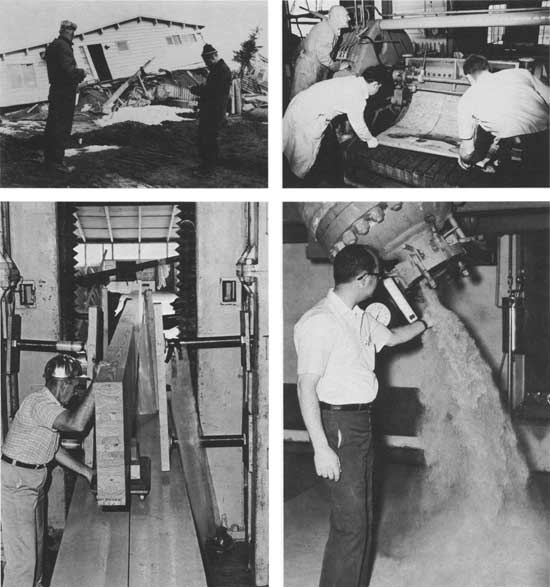

The Forest Products Laboratory . . . 1 (top left). Four days after an

earthquake struck Anchorage, Alaska, in March 1964, FPL engineers were checking the

damage to light, wood frame buildings to evaluate the quake's effects. They found

that well-built wood structures generally survived the quake fairly well. (Forest Products Laboratory, M 126 426 ) 2 (bottom

left). FPL-developed, massive, glued, laminated beams can stand tremendous stress and

strain. A series of binding tests to get data for needed engineering design criteria

was completed in 1969. (Forest Products Laboratory, M 136 997—3 ) 3 (top right). A key 1969 research effort developed by FPL

scientists to increase the yield and quality of wood products. In the process, low-grade

logs are cut into continuous sheets, 7/16-inch thick, peeled from a rotating log by a

knife. The resulting veneer is cut into short strips, press dried, glue laminated,

and made into planks of lumber. Time: 30 minutes. (Forest Products Laboratory, M 139 025—11) 4 (bottom right). Sawdust (in this case,

aspen) as livestock food? It was explored in the late 1960's and demonstrated its value

as such. (Forest Products Laboratory, M 137 451—1)

|

|

|

The Pinchot Institute for Conservation Studies . . . 1 (top left). The Grey

Towers, family home of Gifford Pinchot, Chief Forester 1898-1910, was donated to the Forest

Service by the Pinchot family, along with surrounding forest land, in 1963. It is now the

headquarters of the Pinchot Institute for Conservation Studies in Milford, Pennsylvania.

It has gradually developed into a center for environmental research. (F—508583) 2 (bottom). President

John F. Kennedy dedicated the Institute on September 24, 1963. This was the first stop on

a nationwide conservation-oriented trip by the President. (F—508632)

|

|

|

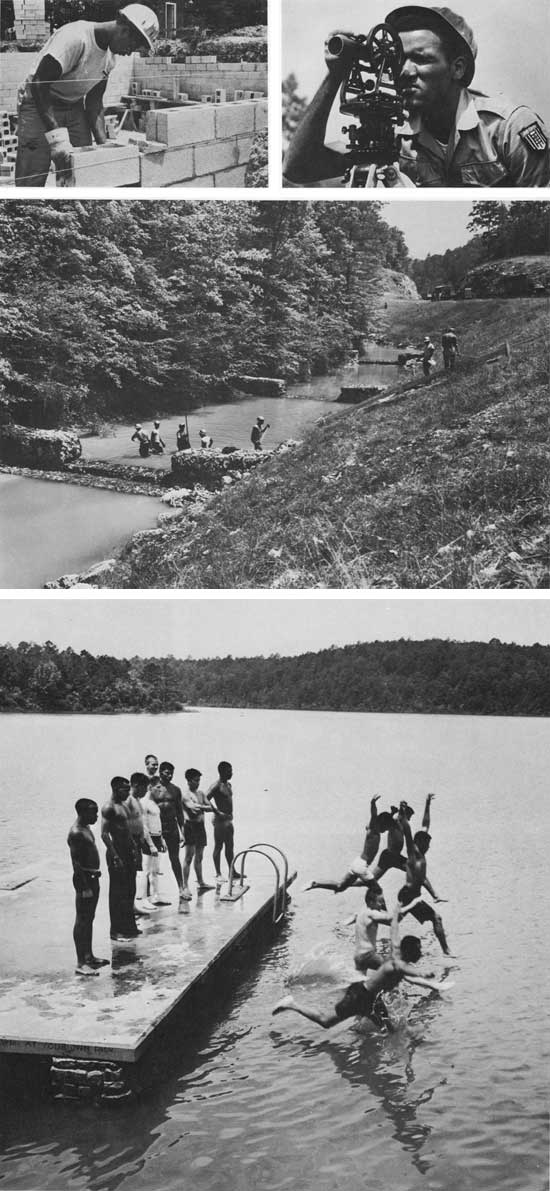

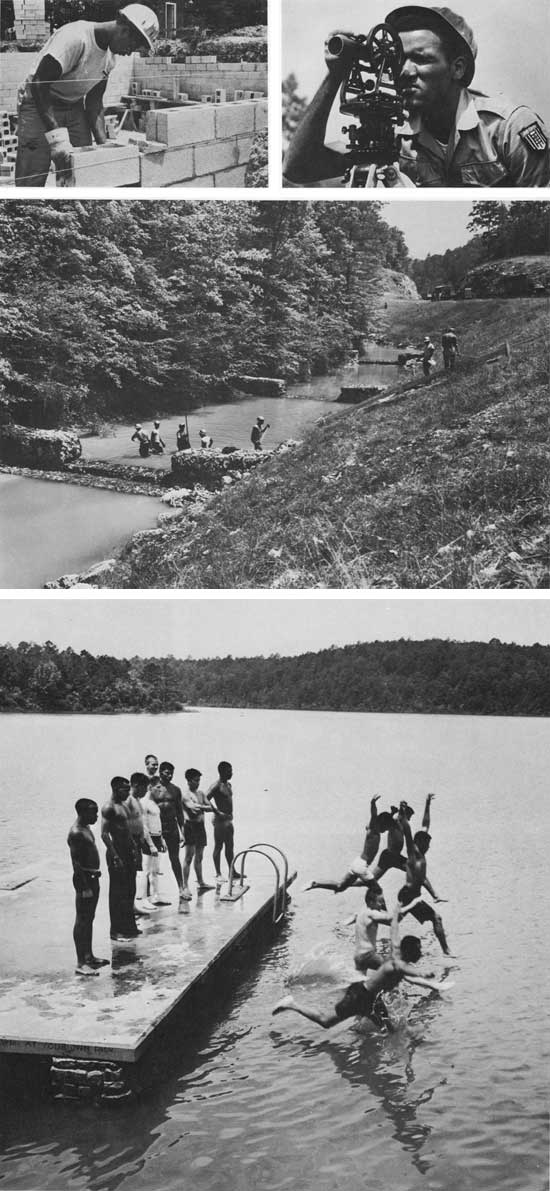

Jobs Corps . . . 1 (top left). In 1965, 8,000 disadvantaged 16-

to 21-year-old youths in the Job Corps were receiving basic education as well as

vocation-skills training in such fields as the construction of buildings . . . (F—519122)

2 (top right). Road surveys . . . (F—516177A) 3 (middle). Watershed protection and stream

improvement . . . (F—514892) 4 (bottom). Lifesaving and waterfront safety. (F—512536)

|

|

|

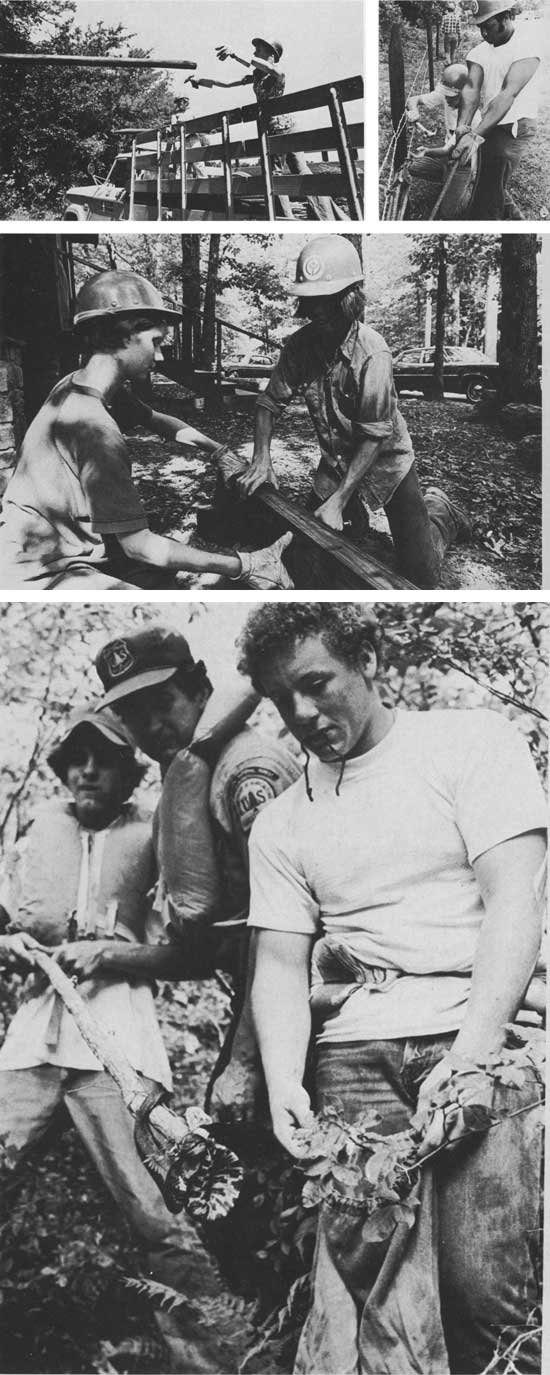

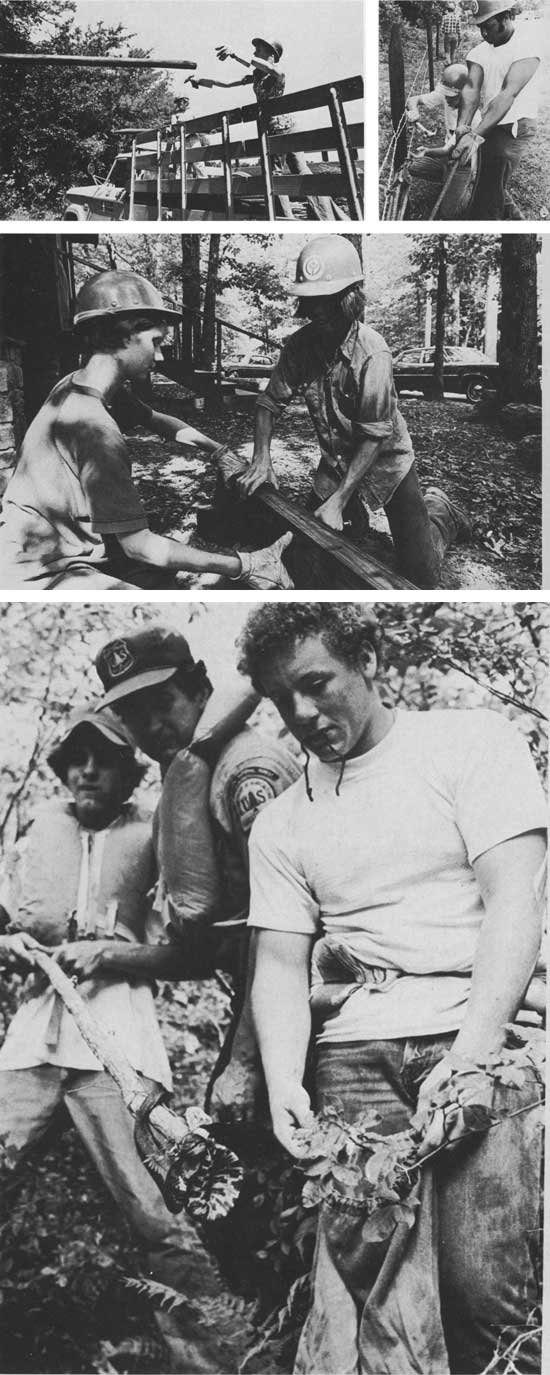

The Youth Conservation Corps is administered by the Forest

Service in cooperation with the Department of the Interior. The objectives:

to do needed conservation work on public lands; to provide gainful summer

employment for young men and women 15 to 18 years old; and to give these

young people the opportunity to gain an understanding and appreciation of

the Nation's environment and heritage. 1 (top left) & 2 (top right).

In 1975, the YCC had almost 13,000 participants in a variety of outdoor

activities, including the installation of fences . . . (Youth Conservation Corps,

0774 R 1138—7A; Youth Conservation Corps, 0774 R 1137—14A )

3 (middle). Construction of barriers to help control erosion and improve the

appearance of recreational areas . . . (Youth Conservation Corps, 0774 R 1134—25)

4 (bottom). Engaging in environmental awareness projects—such as

collecting snakes and other specimens to study for a better understanding of

the natural world. (Youth Conservation Corps, 0774 R 1135—34)

|

|

|

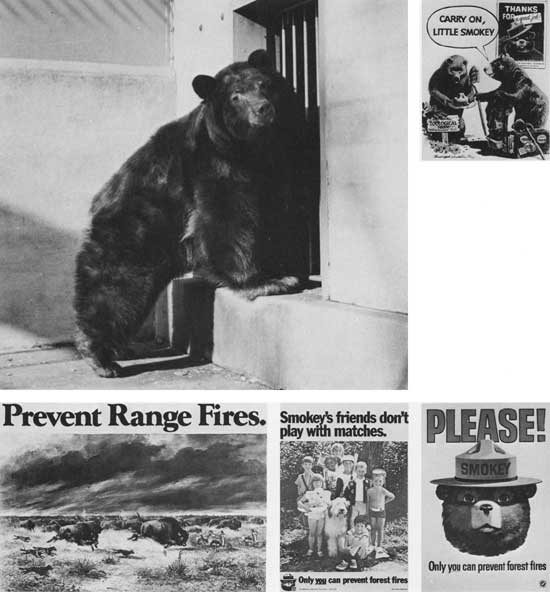

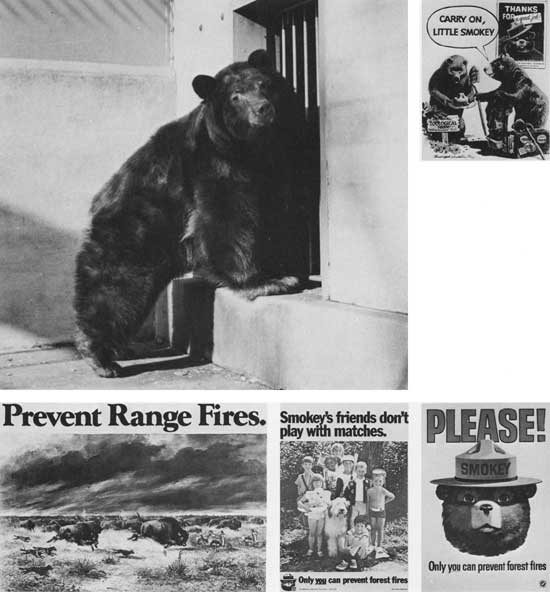

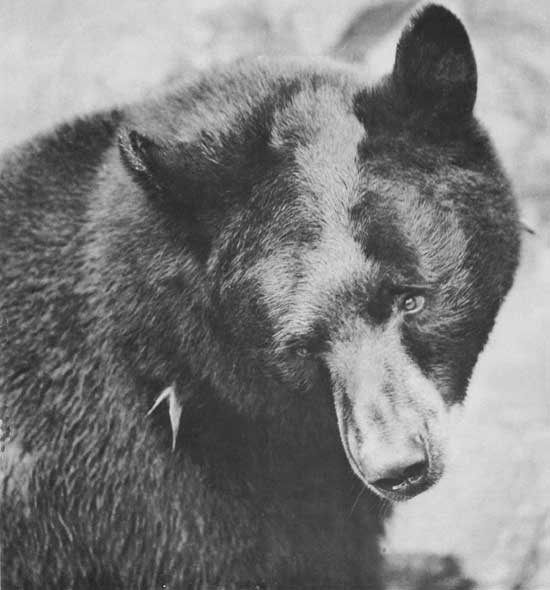

Long live Smokey Bear! 1 (top left) & 2 (top right). May 1975 saw the

original living symbol of forest fire prevention retiring after 25 years at the National

Zoo in Washington, D. C. On the same day, his successor was introduced to the public. (F—510947, Forest Service Cooperative Fire Protection)

3 (bottom left). The Ranger Poster for 1973. (Forest Service Cooperative Fire Protection, Rangeland Poster, 1937) 4 (center bottom) & 5 (bottom right).

Each year there is a poster which headlines the continuing program of the nationwide

forest fire prevention campaign, jointly conducted by the Forest Service and State

Forestry Departments with the cooperation of The Advertising Council, Inc. Many noted

artists and other professional people have supported the program in a practical way.

(Forest Service Cooperative Fire Protection, School Poster, 1968; Forest Service Cooperative Fire Protection, Basic Poster, 1965)

|

|

|

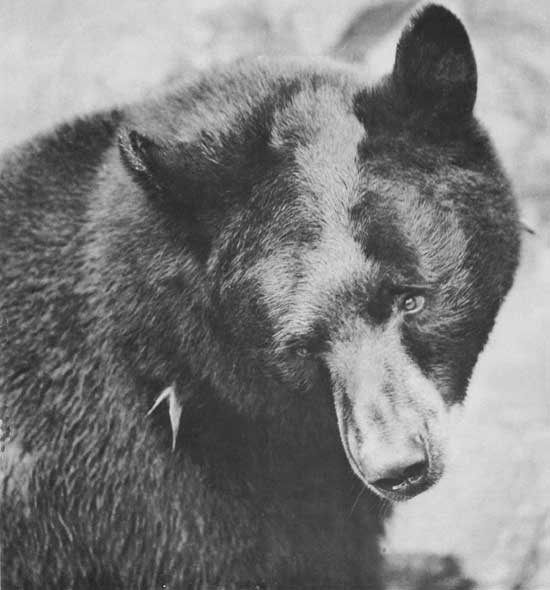

The new living symbol of Smokey Bear also came from New Mexico—the

original home of the first Smokey Bear. He had been abandoned and was searching for food

when he was rescued. After serving as an understudy for 4 years in the National Zoo,

he assumed his new role and greets the many children who come to see him. (Forest Service Cooperative Fire Protection)

|

|

|

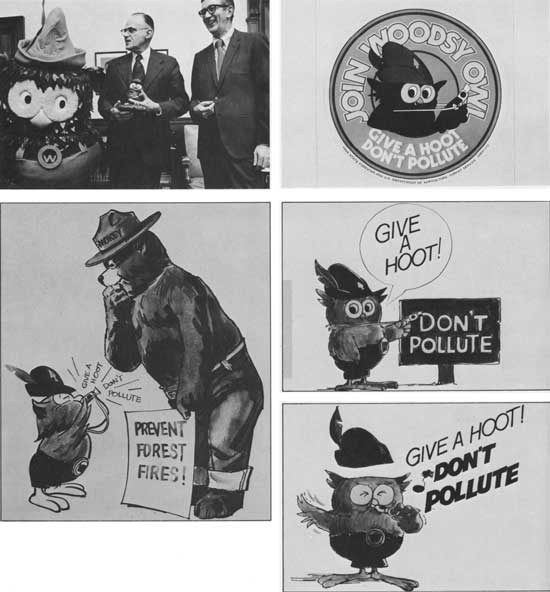

1 (top left). At a planning meeting in 1973, Agriculture Secretary

Earl Butz and Chief Forester John McGuire enjoy a laugh with Woodsy Owl, the Forest

Service's symbol of conventional awareness. (USDA 1272 A 1519—4 ) 2 (bottom left). "Give a hoot, don't

pollute" . . . This was the call heard throughout the land as the fire-preventing

Smokey Bear welcomed a new comrade, the pollution-preventing Woodsy Owl. (F—523664) 3 (top

right). The Woodsy Owl Program is conducted by the Forest Service with the

cooperation of the State Foresters and the Public Service Council. (F—623663) 4 (middle right).

Woodsy Owl made his public debut nationally in September 1971, was legalized as a

member of the U.S. Department of Agriculture conservation team by Act of Congress

in 1974, and set out to capture the imagination and cooperation of young and old

alike. (DN—3301) 5 (bottom right). Children made the decision as to how Woodsy Owl should

look. The environmental symbol represents their views, based on research interviews,

rather than those of adults. (DN—3301)

|

"Wilderness as a form of land-use is, of

course, premised on a qualitative conception of progress. It is premised on

the assumption that enlarging the range of individual experience is as

important as enlarging the number of individuals; that the expansion of

commerce is a means, not an end; that the environment of the American

pioneers had values of its own, and was not merely a punishment which they

endured in order that we might ride in motors. It is premised on the

assumption that the rocks and rills and templed hills of this America

are something more than economic materials, and should not be dedicated

exclusively to economic use . . ."

Aldo Leopold,

Forester and Wilderness Crusader

|

|

The Golden Anniversary of the First Wilderness . . . "June 3,

1924. On this date, the Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture

set aside the Nation's first tract of virtually untouched National Forest (the

Gila) and identified this naturalness as a resource as much so as timber, water,

forage, and wildlife—and called it Wilderness . . ." from the June 1974

"Forest Service News," Southwestern Region, Albuquerque, New Mexico. 1. The

first Wilderness set aside in the United States was the Gila Wilderness in the

Gila National Forest, New Mexico. Today the Gila Wilderness embraces 433,690

acres of wild, unspoiled land. Part of the Mogollon Plateau lies here, and

the area has steep, rugged canyons with many streams and rivers flowing through.

The Gila Wilderness has been extremely popular for its unique historic features,

outstanding scenery, fishing, hunting, and its solitude. (F—495787)

|

|

|

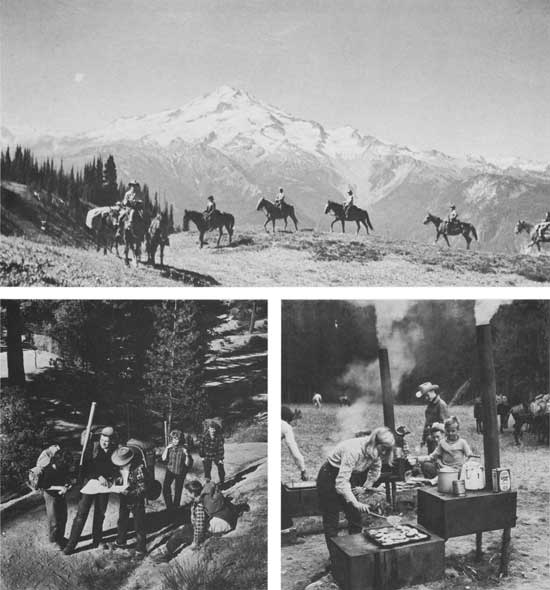

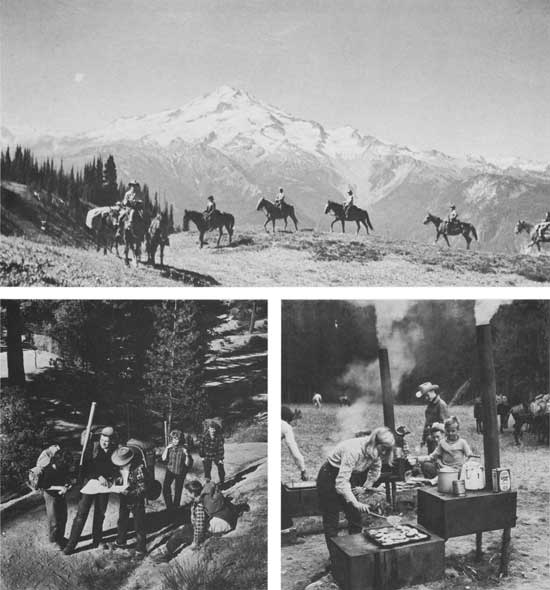

1 (top). Glacier Peak Wilderness Area, Mt. Baker National

Forest, Washington. (F—470126) 2 (bottom left). This family carefully planned their

trip as a picnic ground before heading into the San Gabriel Wilderness

Area, Angeles National Forest, California. (F—503164) 3 (bottom right). Trail riders

camp, Bob Marshall Wilderness Area, Flathead National Forest, Montana.

(F—520822)

|

|

|

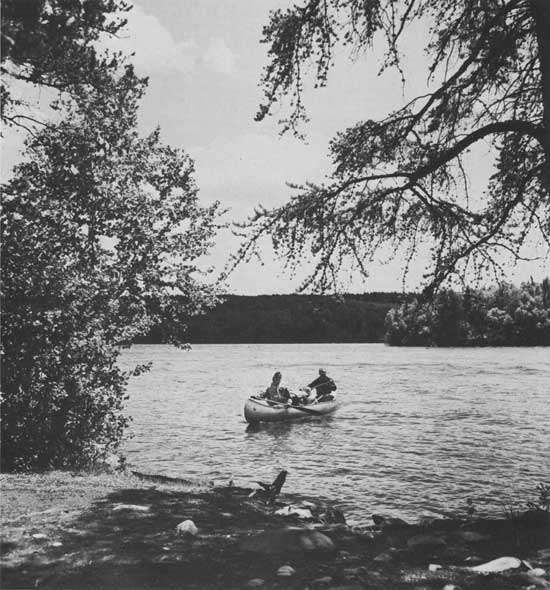

1. Heading for Moose Lake portage, Boundary Waters Canoe

Area (formerly Superior Wilderness), Superior National Forest, Minnesota.

(F—512328)

|

|

|

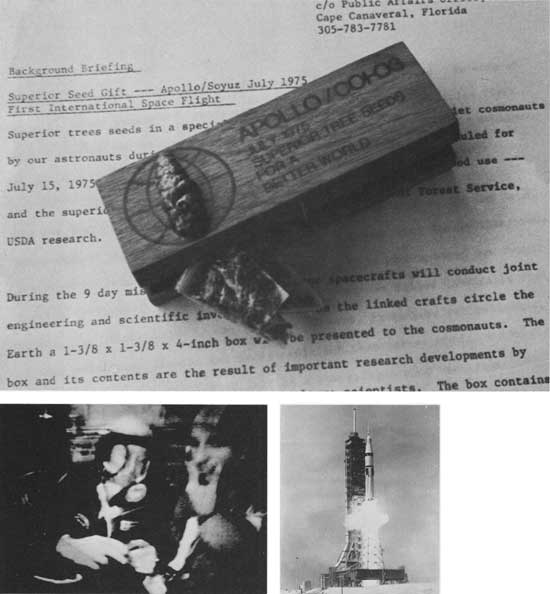

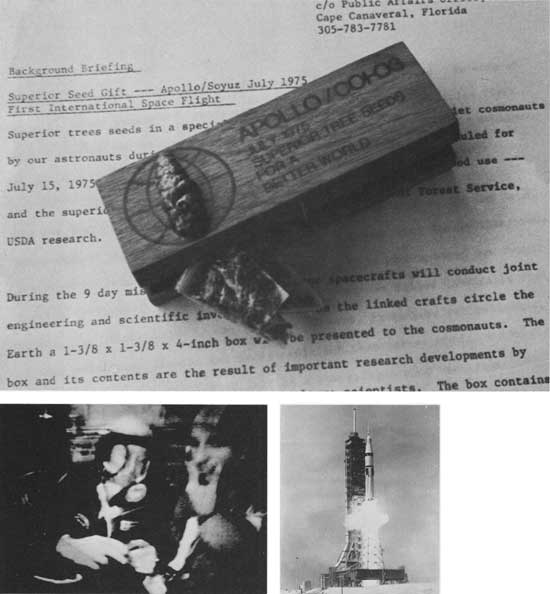

Little seeds to promote international goodwill . . . In an

historic mission in July 1975, during which American and Soviet space vehicles

meet in space for joint engineering and scientific investigations, a small box

of genetically superior white spruce seeds changed hands. The seeds were

developed by Forest Service scientists at the Institute of Forest Genetics

in Rhinelander, Wisconsin, and are expected to produce fast-growing trees of

exceptional height and shape. Enough seeds were given to the Soviet Cosmonauts

to grow an acre in the Moscow area, where the climate is similar to that of

Rhinelander. 1 (top). Small box, large implications. (Apollo-Soyuz Test Project) 2 (bottom left). The giving

of the gift of seeds took place on July 18, after the two craft had docked in

space. Apollo Commander Tom Stafford made the presentation to Soyuz Commander

Aleksey Leonov. (Apollo-Soyuz Test Project) 3 (bottom right). Apollo (a Saturn 1B launch vehicle) took off

for its space adventure with the Soyuz spacecraft in the afternoon of July 15.

The Soviet launch was in the morning of the same day. (National Aeronautics and Space Administration,

75—H—768 108—KSC—75P—392)

|

|

|

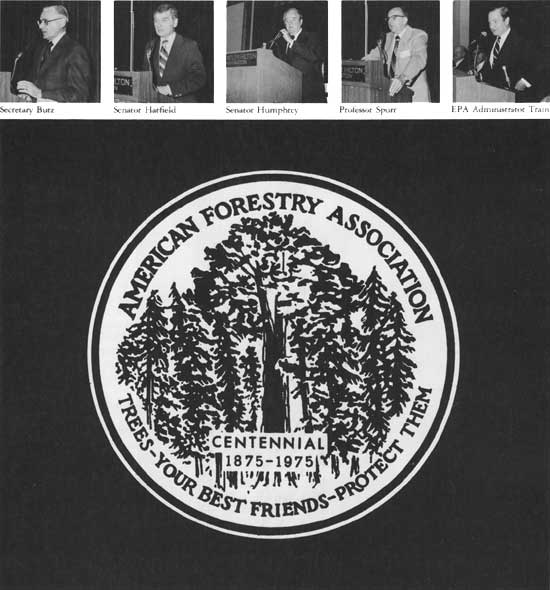

The American Forestry Association's Centennial feature—the

Sixth American Forest Congress . . . ". . . in line with present AFA policy now

in effect, the association's Directors zeroed in on the pressing need for an American

Forest Policy if the nation is to avoid a future forestry crunch not unlike today's

energy crunch. Forest policy, the Board said, is becoming a major national issue

and guidelines set down by Congress are urgently needed to avert or solve future

actions that could hamstring flexible resource management on the land . . ."

"American Forests" December 1975 Participants in AFA's Sixth American Forest Congress

included Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz; Senator Mark Hatfield (Oregon); Senator

Hubert Humphrey (Minnesota), who, with Congressman John Rarick, cosponsored the Forest

and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act of 1974; Administrator of the Environmental

Protection Agency Russell Train; and Dr. Stephen Spurr, University of Texas. These

speakers and others helped launch a national debate on "The Need for an American

Forest Policy." 1 (bottom). American Forestry Association Centennial Emblem. (American Forestry Association photographs)

|

aib-402/sec5.htm

Last Updated: 12-May-2008

|