|

Forests and National Prosperity A Reappraisal of the Forest Situation in the United States |

|

HOW FOREST OWNERSHIP AFFECTS THE OUTLOOK

Many aspects of the forest situation have been discussed, with particular emphasis on timber supplies. Attention now needs to be directed more sharply to the broad problems that are associated with ownership.

Character of ownership largely determines the treatment and management of forests, the stability of forestry enterprises, and the kind of action needed to put the Nation's forests on a permanently productive basis. It is therefore a fundamental factor in the forest situation.

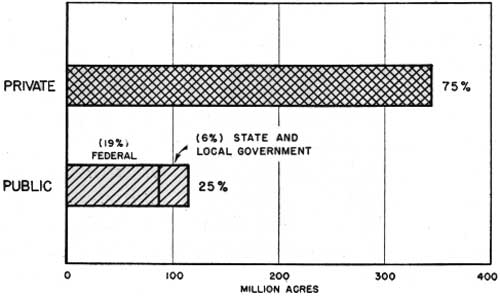

Private ownership, which accounts for two-thirds of all forest land and three-fourths of the commercial, as shown in the following tabulation and figure 27, is of necessity motivated mainly by financial return.

| Ownership of forest

land (million acres) | |||

| All owners | Private | Public | |

| Class of land: | |||

| Commercial | 461 | 345 | 116 |

| Noncommercial | 163 | 64 | 99 |

| Total | 624 | 409 | 215 |

|

| FIGURE 27—Ownership of the 461 million acres of commercial forest. |

Private forestry as a rule must yield revenue commensurate with costs and without long waiting. It therefore centers on those uses, principally timber growing, that produce cash returns.

The need for large-scale public ownership—Federal, State, and local—has largely grown out of limitations that make good management in private ownership uncertain. One of these is the long-deferred or sometimes very small returns from timber crops. Another is the lack of incentive in bettering watershed protection and other services of the forest. Government ownership is relatively free of pressures for immediate revenues. Full recognition can be given to all forest uses and services including those which benefit the general public rather than the individual owner. Public ownership generally affords more assurance of continuity of policies and conservation practices than private ownership. It offers the best opportunity for multiple-use management and for the rehabilitation of forest lands where values are low or are slow to accrue. However, a very large acreage is economically suitable for private forestry.

This basic difference between public and private ownership bears importantly on both the handicaps and opportunities in forestry. But there are also differences among private owners and among the main public categories with respect to purpose, tenure, and stability, and facilities for practicing good forestry.

Public Forests Have An Important Role

Although private forests carry a heavy responsibility, the keystone of American forest conservation policy is permanent public ownership and management of a substantial part of the forest land. This policy, inaugurated in 1891 by the act authorizing the creation of Federal forest reserves, was in part prompted by widespread abuses in and following disposal of the public domain.

Government ownership of forests—Federal, State, and local—has been slowly extended through reservation, purchase, or exchange. Some 215 million acres, about one-third of all the forest land, is publicly owned or managed:

| Publicly owned or managed forest lands, 1945 (million acres) | |||

| All forest |

Commercial | Noncommercial | |

| Administration: | |||

| National forest | 123 | 73 | 50 |

| Other Federal | 54 | 16 | 38 |

| State | 28 | 18 | 10 |

| Local government | 10 | 9 | 1 |

| All public | 215 | 116 | 99 |

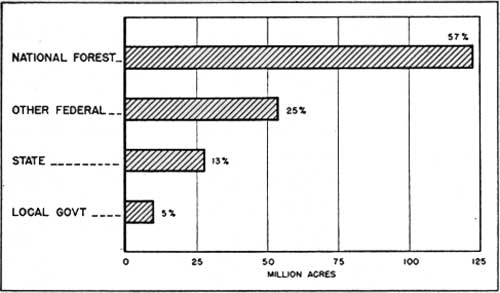

Nearly half of this, however, is noncommercial—the dry-site, scrubby, or reserved forests not suited or available for growing commercial timber though valuable for watershed and other purposes. About four-fifths is Federal (fig. 28), the national forests being the largest category.

|

| FIGURE 28.—Ownership of the 215 million acres of public forest lands. |

National Forests—A Big Undertaking

The national forests, which today stand as the world's greatest public-forest system, include about 180 million acres (net) located in 40 States, Alaska, and Puerto Rico. About 159 million acres of this land is in the United States proper (table 28).

TABLE 28.—Gross and net area in national forests as of June 30, 19461

| Location | Gross acreage within established units |

Net acreage federally owned and under Forest Service administration | |

| All lands | Forest lands | ||

| Million acres | Million acres | Million acres | |

| United States | 207.41 | 158.65 | 123 |

| Alaska | 20.88 | 20.85 | 212 |

| Total | 228.29 | 179.50 | 135 |

1Exclusive of Puerto Rico units which include 186,000 acres, gross, of which about 31,000 is federally owned and administered. 2Rough estimate. | |||

Withdrawals of forest land from the western public domain began in 1891. Six years later these forest reserves were put under administration, and in 1905 jurisdiction was transferred to the Department of Agriculture. In 1907 their name was changed to national forests, as more descriptive of their real character. The Weeks Law (1911) provided the first authority for purchase of lands, and made possible the establishment of national forests in the East. In 1922 a general exchange law authorized exchange of public land or timber for private land.

Of the 123 million acres of forest land in the national forests of the United States proper, about 100 million were withdrawn from the public domain. Some 18 million have been purchased; less than 4 million have been acquired through exchange, and about 1 million have been private gifts or transfers from other Federal agencies.

National forests are managed under four cardinal principles. First is the objective of the public good: "the greatest good to the greatest number of people in the long run." Second is the conservation objective: full and wise use of the forests so as to build up and perpetuate them. Third is multiple use: integrated management of all resources—timber, water, range, recreation, and wildlife—for maximum public benefits. Fourth is decentralized administration: the aim of providing on-the-ground administration in close and constant touch with local, State, and regional conditions and with only enough centralized control to assure that basic policies are effectively carried out.

Placing national-forest lands—in the aggregate about one-twelfth of our total land area—under intensive administration and management has been hampered by the remoteness and inaccessibility of much of the land, by poorly consolidated ownership in many instances, and by inadequate funds. Yet steady progress has been made. Timber, range, water, and other resources are being husbanded through protection, controlled cutting or regulated use, planting and reseeding, and other measures. A basic aim is to bring output up to the full sustained-yield capacity of the land.

Progress would perhaps seem larger if today's needs to get a maximum contribution from national forests were less pressing. As this report emphasizes earlier, the steady depletion of private timber has left the national forests, which include 16 percent of the commercial forest, with nearly a third of the Nation's saw timber. Prior to 1940, much of this timber, in response to public sentiment and economic circumstances, was in a stand-by status. The war marked a turning point. The difficulty in filling urgent timber needs from other sources clearly called for a speedy opening up of additional national-forest supplies. Output was tripled, rising from 1.3 billion board feet in fiscal year 1939 to about 3.8 billion in 1947. It can be further increased in coming years.

Larger demand for national-forest timber has created certain administrative problems. Among them is how to stay within the limits of sustained yield on each working circle—to withstand the pressures to overcut. These pressures often grow out of serious local timber shortages and are accentuated by the urgent need of lumber for housing and other purposes. Nevertheless, adherence in the long run to sustained-yield principles—producing to the full without overcutting the forests, and building up the growing stock where necessary—is fundamental in national-forest management.

Major requisites for increasing national-forest output include a greatly enlarged system of forest roads to open up hitherto inaccessible tracts, mostly in the West; and more sales cutting for thinning and other timber-stand improvement. Looking further ahead, better protection against fire, insects, and disease is also needed to cope with the added hazards that accompany active operation. And planting of denuded areas and fail spots will help maintain output in the future.

More intensive management is needed for other reasons as well. The national forests represent the Nation's greatest opportunity for large-scale multiple-use management. But for this they need physical improvements and much cultural work to put resources in good condition and to assure their most effective use. A great deal of capital-improvement work of various kinds is needed. [37] This should include, in addition to the foregoing: A large amount of range improvement and reseeding; wildlife and recreation facilities, now grossly inadequate; and watershed-protection works to safeguard water and soil.

An important corollary is expansion of the national-forest system—both consolidation of Federal ownership within existing units and establishment of new ones where needed. The rate of acquisition has been far too slow. Regular appropriations, 1910-46, ranged from 75 thousand to 3 million dollars annually. [38] In addition, about 48 million of emergency funds was made available for acquisition from 1934 to 1937. About half of the 18 million acres purchased to date was acquired in those 4 years.

The national forests are a great public asset capable of a much larger sustained output of timber and other products if more intensively managed; They are the backlog of America's public-forest holdings, destined to contribute increasingly to local and national economy. A most pressing need is to get a maximum contribution from them consistent with sound conservation principles. We can do this only by investing more in this resource.

Other Public Forests Are Also Important

The 92 million acres of other public-forest lands also have a large potential for furthering community and national welfare and, in some respects, have similar management problems. Some 10 or more agencies manage the 54 million acres in Federal jurisdiction, most of which is under the Department of the Interior:

| Federally owned or administered forest lands other than national forests1 (million acres) | |||

| All forest |

Commercial | Noncommercial forest | |

| Classification: | |||

| Grazing districts | 17.0 | 1.0 | 16.0 |

| Indian lands | 16.4 | 6.6 | 9.8 |

| Other Federal | 220.3 | 7.8 | 12.5 |

| Total | 53.7 | 15.4 | 38.3 |

|

1Approximate data for 1945. 2Includes about 9 million acres in public domain; 7 million in national parks and monuments; 2 million in Oregon and California revested lands; and 2 million administered by other agencies, including the Reclamation Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, Soil Conservation Service, and the military departments. | |||

The 17 million acres in grazing districts and 9 million in the unreserved public domain—all in the West and administered by the Interior Department's Bureau of Land Management—is mostly noncommercial and of value chiefly for range and watershed protection. Mainly these are arid forest lands intermingled with or merging into open range. Fire protection has been sporadic and management has gone little beyond initial attempts to better the range.

The Oregon and California Railroad and Coos Bay revested lands, about 2 million acres administered by the same bureau, are of special importance because of their unusually high timber values. These lands are in 18 counties in western Oregon in alternate sections, checker-boarded with national-forest and private tracts. Congress in 1937 established for the O&C lands a policy of sustained yield timber management. [39] A substantial sale business with conservative cutting is being carried on. They are generally given good fire protection through cooperative associations or the Forest Service. Active effort is being made to organize cooperative sustained-yield units with owners of intermingled lands.

More than 16 million acres—about 40 percent commercial—is administered in trust for the Indians by the Office of Indian Affairs. Timber-sale policies aim at maximum financial returns consistent with good silviculture and watershed protection. Forest ranges are also under management. In general, protection and management are believed to approximate national-forest practices, especially in the West.

The national parks and monuments, administered by the National Park Service of the Department of the Interior, include about 7 million acres of forest land possessing outstanding scenic, historic, or scientific values. Commercial use of timber and most other products is excluded. The forests are kept in natural condition and hence afford good watershed protection and serve as important wildlife refuges.

Other Federal forest lands, totaling about 2 million acres, are administered by the Reclamation Service and the Fish and Wildlife Service of the Interior Department, the Soil Conservation Service of the Department of Agriculture, the military departments, and other agencies. Some, like the lands in military reservations and those acquired in farm resettlement purchases, are subject to transfer or other disposal. Others such as wildlife areas are under permanent management for purposes other than timber growing. Most, however, are in varying degree protected and under conservative management.

State and local governments own or manage under lease nearly 38 million acres of forest land, about two-thirds in the North and most of the remainder in the West:

| State and local government ownership of forest land, 19451 (million acres) | |||

| State | Local | Total | |

| Section: | |||

| North | 16.3 | 8.3 | 24.6 |

| South | 2.4 | .2 | 2.6 |

| West | 8.7 | 1.9 | 10.6 |

| United States | 27.4 | 10.4 | 37.8 |

| 1Includes lands under long-term lease from the Federal Government. | |||

They are increasing their holdings. Lands under State administration have grown from 19 million acres in 1938 to nearly 28 million in 1945 through purchase, lease, and taking over tax-reverted properties.

Some 38 States have a policy of establishing and managing State forests. A good proportion of the State lands has been blocked up as State forests, parks, or game refuges. Much, however, remains in scattered unorganized tracts, a great deal of it tax-reverted and in an uncertain ownership and management status. Lack of clear-cut policies handicaps a number of States in putting these lands in productive condition.

Administration and use both vary greatly. Nearly all State forest lands are protected against fire and trespass. Management, particularly of recreational resources, is in some cases good although many essential facilities are lacking. Timber management is excellent in some States, and on the average distinctly better than on private lands.

The expansion of State forests in recent years has found many State forestry agencies badly underequipped to do the work required of them. Some are hard-pressed to provide even the minimum of fire protection and to keep up roads, fire towers, and other facilities built and formerly maintained with the help of the Civilian Conservation Corps. To put State forest lands under satisfactory management, and particularly to get the 18 million acres of commercial forest into planned timber production, is difficult with present facilities. Fortunately forest administration is being strengthened in some States.

Local-government forest lands are a growing class and, in some respects, closest to the people. Despite the rather small acreage, they are contributing to the forestry movement, especially in New England and the Lake States. Of some 10 million acres, chiefly commercial, which is owned by counties, municipalities, schools, and other local public organizations, about 4-1/2 million is managed as community forests. These are in more than 3,000 units in 43 States. A few date back a great many years, although most are of recent establishment.

These forests help meet community needs for watershed protection, readily accessible recreational facilities, and other public services—not to mention timber and the revenue to be derived from it. Some, especially the municipal forests managed primarily for water supply, receive excellent management. It remains to be seen how well local governments can build up and maintain forests, how well they can resist pressure to exploit them for immediate income. Some sales of these lands already made may prove to have been unwise. However, community forests are a promising development and can do much to stimulate local interest and understanding of opportunities and needs in forestry.

Extension of Public Ownership

Early land-disposal policies shifted to private ownership much forest land that should have remained in public hands. True, this made for a speedy opening up and use of forest resources, but to accomplish the sterner tasks of rehabilitation and permanent management enlarged public ownership is needed.

Just how much additional forest land should go back into public ownership depends on many factors including the extent of effective private management. But there are substantial acreages whose values and location unmistakably best suit them to public ownership—Federal, State, or local. [40] Principally these are in six categories:

1. Lands where soil, climate, or species make for such slow growth or poor quality that there is little incentive for good private forestry.

2. Lands so depleted of timber growing stock that the needed heavy outlays for rehabilitation and the long waiting make net returns too small and uncertain to attract private capital.

3. Lands where private ownership results in such inadequate management as seriously to threaten stable supplies of forest products, and the dependent communities and industries.

4. Forest lands vital to control and use of water, where private ownership cannot assure good watershed management.

5. Forests of high value for recreation, wildlife propagation, and other public services, where private ownership will not afford adequate development or access.

6. Lands so intermingled with or integrally related to public forests that their separate ownership seriously hampers administration and management of the public lands.

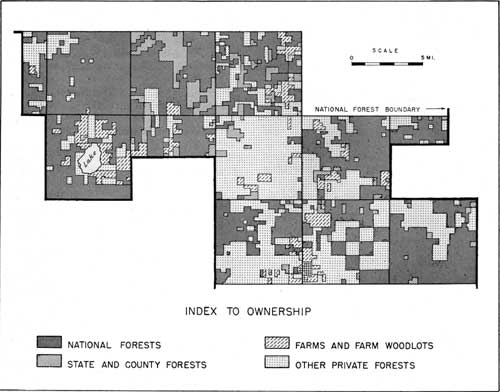

Of high priority is the acquisition of a large acreage in the last category—the intermingled lands. In the West, much national-forest and other Federal land forms a checkered pattern of alternate mile-square sections, interspersed with private and other holdings that were alienated in this fashion from the public domain. Within the exterior boundaries of other national forests, the pattern of ownership is somewhat similarly patchy, though not in a regular checkerboard (fig. 29). In some units of the eastern national forests, Federal ownership constitutes less than half of the total. Within the boundaries of all national forests, there are nearly 50 million of alienated land of which, it is estimated, some 35 million should be acquired. Some State forests are similarly broken up, and many are in small, widely scattered units.

|

| FIGURE 29.—A typical eastern national-forest area, in Wisconsin, showing intermingled ownership. Such patchy holdings usually are difficult to administer. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Patchwork ownership adds to the difficulties in protecting forests, in laying out satisfactory road systems, in managing timber and other resources, and, indeed, in exercising most management functions. Although cooperative management of public and private lands under sustained-yield agreements [41] will meet the needs in some localities, consolidation through purchase or exchange is the chief means of unscrambling the jigsaw pattern which so often impedes effective administration of public forests.

Progress in acquisition has been much too slow. This reflects public apathy—mostly lack of understanding of forestry needs and of what public forests can contribute to local economic and industrial welfare. Then, too, there is opposition in some localities motivated by fear of government encroachment into private affairs. On the other hand, local interest and initiative are responsible for much public acquisition. As yet, the general public is not well informed of its large stake in stable, effective management of forest land on which public values are paramount or where private forestry is clearly a losing game.

Opposition to enlarging the national forests is often based on the effect of public ownership on local tax revenues. This usually overlooks the indirect benefits and payrolls which national-forest protection and development bring to the local communities. It also overlooks the fact that to a large extent acquisition involves cut-over or low-value lands, much of which would yield little tax revenue had they remained in private ownership. Yet it is evident that Federal financial contributions to local governments on account of Federal ownership should be put on a more uniform and stable basis. At present there is no consistent contribution policy; in some instances no Federal payment at all is made.

The national forests pay 25 percent of gross receipts to the States for redistribution to the counties in which the forests are located. [42] In addition 10 percent of the receipts are appropriated for construction of roads and trails in these counties. [43] This generally affords adequate returns to local government, especially since there have been very substantial increases in national-forest receipts in recent years. However, there are local inequities, particularly where the tax base is limited and where forest land is so depleted that it will yield only nominal revenue for many years.

A main difficulty is that the present system of contribution does not always afford a stable source of revenue for local government. National-forest receipts, chiefly from timber sales, may fluctuate greatly from year to year. Moreover, there are other disadvantages: use of Federal contributions is limited to support of roads and schools, and the method of apportioning the funds to counties—on an acreage basis—is not always equitable.

In recent years a number of bills have been introduced in Congress to stabilize Federal contributions and to afford a more satisfactory method of apportionment. In general, the Forest Service favors annual payment of an equitable percentage of fair value of the land—probably about three-fourths of 1 percent—with no restrictions on how the money is spent.

Private Ownership Is Widely Divided

The ownership pattern of the 345 million acres of private commercial forest is largely the result of national land policies which, from the beginning, favored small-scale, fee-simple ownership of the bulk of the lands. From this stems much of the prodigal use and waste of forests. In some respects it enhances forestry opportunities, but in others greatly complicates the job of getting good forestry practiced.

Because of the variety and number of owners, private forestry lacks a concerted policy. Its aims are varied, as individualistic as several million owners, each with his own purposes or lack of them in land ownership and management, and each with his own particular advantages or handicaps in practicing forestry.

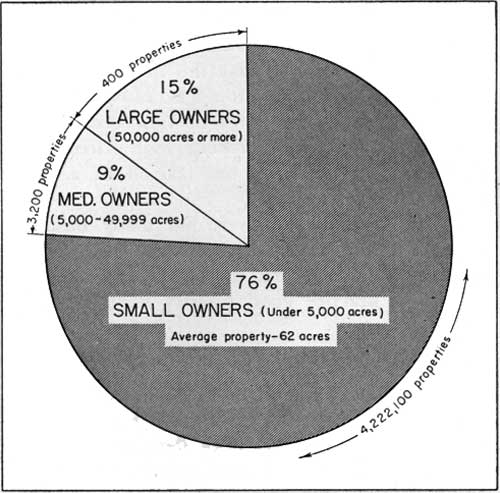

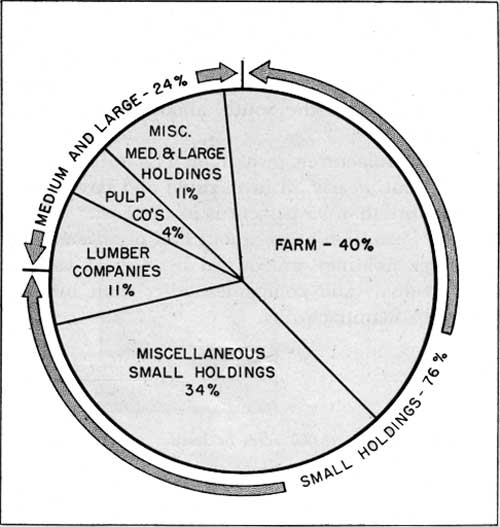

Perhaps the most significant fact about private ownership is that 76 percent of the private commercial forest is in more than 4 million small properties averaging only 62 acres (fig. 30). Only 3,600 owners hold the other 24 percent in medium and large properties. Even in the West more than half is in small holdings. In the North and South 84 and 73 percent, respectively, is in this category.

|

| FIGURE 30.—Ownership of the 345 million acres of private commercial forest land, by size of holding. |

Farms include 40 percent (139 million acres) of the private commercial forest, as shown in figure 31 and the following tabulation.

|

| FIGURE 31.—Distribution of private commercial forest land by class of ownership. |

About 125 million acres is in other small holdings. Of this, lumber manufacturers own 10 million acres, pulp companies another half million. But the great bulk is held by a variety of mainly absentee owners.

Wood-using industries, directly dependent on timberlands for their raw material own a surprisingly small part of the private commercial forest. Lumber manufacturers own some 37 million acres or 11 percent, about three-fourths in medium and large holdings. Nearly 45 percent of lumber-company lands are in the South, about 40 percent in the West.

Pulp manufacturers own about 14.5 million acres or 4 percent, nearly all in medium and large holdings. More than 95 percent is in the East.

Some 43 million acres—about half of all medium and large holdings—are owned by a great variety of individuals and companies other than lumber and pulp manufacturers.

| Private commercial forest land | ||

| Million acres |

Percent | |

| Ownership class: | ||

| Small holdings (5,000 acres or less): | ||

| Farm | 1136 | 40 |

| Other | 2125 | 35 |

| Total | 261 | 76 |

| Medium and large holdings (more than 5,000 acres): | ||

| Lumber company | 27 | 8 |

| Pulp company | 14 | 4 |

| Other | 43 | 12 |

| Total | 84 | 24 |

| All private | 345 | 100 |

|

1Total acreage on farms is 139 million acres, 3 million in holdings

larger than 5,000 acres. 2Includes 10 million acres of lumber-company holdings; about 0.5 million of pulp-company lands. | ||

Whatever the class of ownership, there is ample evidence that private forestry pays and is good business. The more profitable opportunities occur where timber grows fast and markets are favorable, and particularly where there is enough accessible growing stock to operate with continuous revenue. The South, with its rapid timber growth, now offers the best example. In the North, good markets are a special advantage. Throughout the country, a growing number of owners have started the practice of forestry. Today this movement is favored by high prices. Although no cause for jubilation from the public point of view because they are a symptom of timber scarcity, high prices should be helpful in powering the take-off of a larger forestry movement.

Private forestry, however, has many obstacles, some of which are implicit in the small size of holdings. Furthermore, the means and ability of owners to practice good forestry vary widely.

Larger Owners Have Some Advantages

Of the 84 million acres in 3,600 medium and large properties, the 41 million of pulp- and lumber-company lands especially lend themselves to good forestry. Their owners usually have the facilities including the financial strength needed to undertake sustained-yield forestry, granted the intent to practice it and the aim to keep mills and plants operating on a permanent basis. Much progress is being made. Yet even here, the fact that four-tenths of the cutting is poor or destructive (see p. 49) shows that many of these lands still lack stable, proposeful management.

Lumber-company ownership of forests is still exploitive in many instances. Generally, however, it has in recent years been becoming more stable. Today the objective of many owners is to integrate woods and mill for permanent operation. The number of operators who have achieved this seems to be increasing. Balance is being gained through measures to increase the allowable cut of timber—rehabilitating cut-over lands, managing and protecting merchantable areas, and acquiring more lands. In some cases balance is being sought also through scaling down and modernizing plant facilities.

Cooperation between public and private owners to pool holdings into sustained-yield units will help stabilize lumber enterprises and the communities dependent on them. The sustained-yield unit act of 1944, [44] authorizes agreements between the Secretary of Agriculture and willing private or public forest owners for sustained-yield management of interrelated national-forest and other lands. In return for committing his lands to a coordinated management plan, the operator can purchase national-forest timber without competition at the appraised value. The Act gives similar authority to the Secretary of the Interior with respect to lands under his jurisdiction.

One unit has been set up by the Secretary of Agriculture, and negotiations are under way for several others. It is tentatively estimated that from 20 to 25 percent of the commercial area of the national forests eventually might be included in such units.

The pulp industry—with heavy long-term investment in plant and equipment, dependence upon a steady flow of pulpwood, and ability to use small trees—is making the best showing in private forestry. The pulp industry's southward movement has been attended by acquisition of much southern pine forest. About two-thirds of pulp-company lands are under at least extensive management (see pp. 50-51), but there is still a big forestry job to be done in building up their productivity.

The 43 million acres of large and medium properties not in lumber- or pulp-company ownership are held by a variety of individuals and companies: Railroads, mining and land concerns, large estates, institutional and private investors, speculators, and even a few farmers. Policies are diverse and usually not conducive to good forestry. In the case of railroad, mining-company, and some institutional or estate forests, ownership—though incidental to other aims—is reasonably stable. Here there is usually a sound basis for good forestry though the opportunities for the most part are going begging. In many other instances ownership—by banks, mortgagors, private investors, and the like—is temporary and affords poor prospect for private forestry. Yet even temporary owners have a stake in protection and other measures that would safeguard their investment.

In assessing the progress by larger owners one question naturally arises: Whence has come the upturn in forestry practice and is it permanent? The declining supply of timber, growing public awareness of the seriousness of the forest situation, and a tendency to associate destructive practices with large-scale private ownership doubtless have been important factors. Spurred on by such considerations, the timber-trade and other industrial associations have publicized forest conservation and have encouraged members to put it into practice.

But the present movement has gained momentum largely because of the favorable economic climate in which these forces have operated. Demand and prices for forest products have been high. Forest-land prices in many cases have until recently been low. High income-tax rates have, in effect, reduced the net cost of expenditures for forestry. The whole movement may mark the beginning of a long upward trend. Or it may level off if economic conditions become less favorable.

Despite these encouraging advances, the fact remains that more than half the land in medium and large holdings is without purposeful forestry management. [45] There are as yet few examples of private timber growing where long waiting is involved. A waxing private interest in forest conservation where market and growth conditions are favorable should not obscure the unmet challenge of many millions of other acres whose output is needed to help fill the Nation's wood box but whose depleted condition or small return is unattractive to private enterprise unless heavy public support is forthcoming.

Small Forest Owners: The Heart of the Problem

The more formidable obstacles in private forestry center, however, on the more than 4 million small properties which total about three-fourths of the private land. Their large number and small size, the variable aims and skill with which they are handled, and the unstable ownership and management of many—these are knotty factors which long have blocked efforts to get forest conservation into more general practice.

The 139 million acres of farm woods are held largely in conjunction with property managed for other purposes. To the individual farmer, his woodland is usually a minor resource. Yet farm woodland is the largest category of forest land, and hence is of great national importance.

Farm ownership generally affords a favorable setting for forestry. It is comparatively stable and enables a maximum of on-the-ground managerial attention. Farm forestry requires little cash outlay. Mostly it utilizes time not fully employed on other farm jobs.

Public policy has long sought to make woodland management an integral part of the farm business. However, such management is not yet extensively practiced. With the greatest opportunities for intensive forestry, farmers still lack, as a class, the knowledge and incentives to practice it. Even with the advances that have been made in aiding farm forestry—in education, technical assistance, and incentive payments—most farm woodlands are still the backyard of the farm, subjected to thoughtless cutting, pasturing, and burning.

The 125 million acres of other small holdings are in many respects a more difficult problem. They have received little if any attention in aid programs, yet are an inseparable part of the agricultural problem of rural people and of rural land. Furthermore, forestry on both nonfarm and farm properties is beset by similar handicaps which call for much the same remedial program.

The small nonfarm woodlands, like the larger properties, are held by people and companies of the widest diversity of purposes as owners. Many become owners by default, by inheritance, or in some other fortuitous manner. Some have put money into timber. Some are sawmill operators. Many are investors in minerals or in potential farming sites, and the forest to them is secondary. Still others hold the land for a variety of purposes, some for reasons of sentiment. The great majority are absentee owners.

A major handicap, as with the farmer owner, is lack of forestry know-how—of how to grow, harvest, and market timber to best advantage. Most small owners and operators lack the experience to perform or supervise these tasks expertly. They need much technical information and on-the-ground assistance in forest management. Here there is constructive opportunity for public aid on a greatly enlarged scale.

Small size, of itself, also entails handicaps. Small holdings, particularly if badly depleted, may be commensurate neither with the income needs of the owner nor with the labor and other investments he might put into them. Small size usually means that the operator grows, harvests, and markets timber as a side line. As a seller, he often is unable to reach good markets. With small output and returns, there is little incentive to practice good timber management.

The cooperative association long used by farmers in overcoming the handicaps of smallness has application to forestry. Since the first "forest cooperative" was organized in this country, more than 40 years ago, the movement has shown sporadic growth. Many associations have failed. A few have had long and successful histories. During the past 10 years or so there appear to have been some 57 forest-cooperative associations of different types, but engaged chiefly in marketing farm timber. Most are in the Lake and other northern States where farm cooperatives have prospered. Some handle timber only; some, as a side line to farm commodities. At least one processes the timber of members before selling the products. Some also provide timber-management service and require adherence to good cutting practices. [46]

Forest cooperatives, given needed encouragement by public agencies, should help to meet the problems of the small forest owner.

Closely associated with small size is low income. There is many a small property, farm and nonfarm, whose owner or operator is hard-pressed financially and which has been picked over for every bit of income it will yield. In most of these cases the forest is shorn of merchantable timber and will not produce much for many years. Meanwhile the poverty of the owner perpetuates the poverty of his forest; he cannot afford to postpone what little income there is while growing stock is being built up.

Such very low-income forest properties, it is roughly estimated, total about 65 million acres or one-fourth of the commercial land in small holdings. These are concentrated in the more depressed rural areas, where natural and industrial resources are limited: the Piedmont and Coastal Plain of the South, the southern and central highlands from the Appalachians to the Ozarks, and the northern Lake States.

There are no simple solutions to the tough problem of rehabilitating these small, low-income properties in the face of the economic pressures which keep them depleted. Rehabilitation in any event will be slow and will involve recreating the people's whole resource base so as to raise their total income. In the more depressed areas, it is improbable that growing stock can be restored while there is still a heavy population on the land and the forests remain in private ownership.

Absentee ownership is another serious obstacle. [47] When an owner leaves his property unoccupied or turns it over to a tenant, good forest management is doubly difficult to attain.

Despite the poor showing by small holdings as a class, there is opportunity for forestry on a large proportion of them. But the present picture is largely one of mismanagement, of exploitation on millions of small properties adding up to exploitation on a grand scale. The picture reveals serious handicaps, economic and physical, to satisfactory forestry. It reveals the heavy handicap of sheer lack of knowledge of forestry and its possibilities. Yet if private forestry is to do the job it needs to do, it must prove itself on these small holdings as well as on the larger ones—for in these is three-fourths of the private commercial forest. The small property is indeed the crux of our forest problem.

Some Economic Factors Affecting Private Forestry

The job in private forestry is one of getting permanent sustained-yield management that will not only profit the owner but also serve the public interest. The public's part of the job is largely a matter of minimizing the handicaps—of making private forestry more attractive, and helping private owners see and make the most of their opportunities. It also involves protecting the heavy investments which the public should shoulder in helping to spread good private forestry.

Some of the more obvious needs such as better forest protection, more technical assistance in forestry, and the like, are implicit in the difficulties confronting private owners—especially those relating to small properties. But there are several other things that affect ownership and management of private forests:

First, there is need for adequate financing. Forestry is a long-time enterprise. It involves long-term investments—not merely the capital for year-to-year operation but that required to build up a satisfactory growing stock.

The problem of waiting—of financial forbearance—is no small one. For example, the lumber company with high-interest-rate loans on mature forest may have to choose between liquidation or default. The timber-operator who gets capital at high cost from the buyers of his product may find himself forced into exploitive practices. The private timber owner, especially the small one, usually must put his need for current income ahead of long-run considerations. To all these, waiting is expensive—often too expensive to afford.

The problem of financing private forests also includes making needed adjustments—enlarging timber holdings to economical operating size; planting, stand improvement, and other measures; revamping of road or mill layout; and the like. All this calls for financing at reasonable cost. The chief need is low-interest-rate credit for periods ranging up to 40 or even 60 years while growing stock is being built up. Some loans are needed to finance operations or improvements that will pay off more quickly.

Forest owners and operators generally lack sources of satisfactory credit—long-term or intermediate—adapted to their special needs. Today, when specialized credit facilities for farming and for industry have been developed to a high state of efficiency by both public and private agencies, forestry is the outstanding category where credit needs remain neglected.

Second, there is need for forest insurance. Risks from fire, insects, disease, and other destructive agents are not only reducible but also insurable. Forest insurance is well established in several European countries. But in this country, although commercial companies have given considerable attention to the possibilities and have written some policies at high rates, forest insurance has been slow to catch on. Studies in the Pacific Northwest and the Northeast [48] indicate that commercial insurance is practicable at reasonable rates if it avoids poor risks and is based on good protection, reasonably good forest practices, and broad coverage.

Third, property taxes have long been regarded as a major obstacle to private forestry. Annual taxes, to be sure, may encourage premature cutting or abandonment of young or cut-over forests. Furthermore, the fact that taxes are considered an obstacle tends to make them so.

However, the effect of property taxes as a deterrent to forestry has generally been exaggerated. Management of farm woods, for example, is little affected because they are seldom taxed separately from the rest of the farm and the costs chargeable to them are rarely segregated. Less than half the private land is likely to be influenced in its management by property taxes, and only a fraction of this probably is appreciably affected.

An important factor in the tax burden is poor administration. Inequities in assessment as between forest and other land, as well as unpredictable fluctuations in the tax, create special burdens on forest owners. High costs of local government complicate the problem, especially where forests are the main tax base and depletion is widespread.

Some of these burdens are being lightened. Many States are giving increasing help to local governments in making more uniform and equitable assessments. Some States are assuming the support of roads, schools, and other services formerly borne by counties and districts, and some have limited the local tax rates by statute. Between 1932 and 1941, costs of State and local government rose from 8.5 to 12.8 billion dollars, but property taxes remained at about 4.5 billion dollars. Meanwhile tax delinquency, a sensitive barometer, has fallen to a long-time low.

Even so, forest taxation remains much in the public eye as indicated by the continuing stream of legislation. As of 1946 twenty-six States had special forest-tax laws on the books. Mostly this is exemption and yield-tax legislation of the optional variety [49] which has proved largely ineffective. In no State is more than 8 percent of the private commercial forest land classified under such laws, and in more than half less than 1 percent. Only two States, Ohio and Washington, have differential or deferred forest taxation [50] of the type recommended by the Forest Service more than 10 years ago.[51]

That Federal and State income taxes seriously hamper good forest practice is doubtful because they do not reach the great mass of owners, nor those who are making no net income. Indeed, the high tax rates of recent years may have encouraged concerns with high income to spend more for forestry. State and Federal estate taxes occasionally have some adverse influence, but most forest properties, including those of corporations, are not subject to them and few are subject to upper-bracket rates.

Public Interest in Private Forests Should Be Safeguarded

To keep all forest land reasonably productive, there is need for some public restraints upon cutting and other practices on lands in private ownership. The public should set up common-sense rules that will prevent clear-cutting without provision for restocking, stop unnecessary destruction of young growth, and require reasonable safeguards with respect to fire, grazing, and logging.

This is an essential step to assure sound private forestry. Owners, large and small, have a vital stake in the kind of forestry practiced on each other's land since "cut-out-and-get-out" practices have a direct bearing on the stability and strength of local markets which are so advantageous to profitable private forestry. Indeed, good cutting practices, such as are already being attained on many private holdings, are in the long run one of the best guarantees of vigor and permanence of industries and communities, as well as of the forestry enterprises that sustain them.

Basically, the need for regulation stems from the large responsibility to safeguard forest values in the interests of society as a whole. The authority of government to impose reasonable restrictions on personal and property rights of individuals to prevent injury to the public welfare is a widely accepted principle of law. This is reflected by a large and growing body of regulatory laws—Federal, State, and local—of which there are many common place examples: Speed laws, zoning ordinances, sanitation and building codes; and regulations affecting such broad fields as commerce, transportation, public health, and conservation and use of national resources. The public, to whom private forestry looks increasingly for financial aid and other services, needs some minimum guarantee, such as regulation affords, that forest lands will be kept productive and that its large investment will be protected.

Regulation of private forest practices has in recent years won considerable acceptance in principle, although there is also much opposition to it and much controversy about whether it should be State or Federal. Nowhere as yet, in this country, is it on a satisfactory basis. Some 14 States now have regulatory laws on their books, 3 of them enacted prior to 1925 and 10 in or since 1940. Since 1940, unsuccessful efforts have been made in 10 other States to pass regulatory laws.

Some of the laws specify definite rules of practice: usually that seed trees be kept or that the cutting be limited by diameter. A majority place responsibility on a single State agency, which is a requisite of good administration. Less than half, however, provide for the needed advice and assistance to forest owners and operators. Only a few are believed to provide adequately for enforcement. In most, the silvicultural standards require little or no improvement in the prevalent cutting practices. In some States the law is to all intents and purposes a dead letter.

There are many obstacles to getting effective regulation, Nation-wide, based solely on State-by-State action. Progress would be exceedingly slow. Some States might not act at all. And results doubtless would be spotty. They would probably vary from very little in some States to a good job in some financially strong States with good laws and effective enforcement. Regulation probably would be poorest in extensively forested States where it ought to be best. States with good standards of practice would be under continual pressure to lower them if competitive States observed lower ones.

Federal leadership and participation are needed to assure satisfactory regulation, Nation-wide. This was recognized as long ago as 1920, when the first Federal bill for forest regulation was introduced in the Congress. Several regulatory bills have been introduced in Congresses during recent years; none has been enacted. Some have proposed outright Federal regulation. One would give the States reasonable opportunity to enact, and with Federal financial assistance administer, regulatory laws consistent with basic Federal standards; and would provide for Federal administration under the Federal law in States which after a reasonable time failed to do so.

Key Issues Related to Ownership

This discussion has focused on some of the difficulties confronting forest owners—private and public—and has also shown that, on every hand, the outcome in forestry is bound up with getting stable, purposeful ownership of forest land. Indeed, it also points up three fundamental and interrelated problems which, in large measure, highlight the job to be done in bettering our forest situation:

1. How to achieve good forestry under private ownership.

2. How to protect the public interest in poor-chance forests that are not readily susceptible of good management under private ownership.

3. How to equip public forests so that they may contribute more, as they must, to our national supply of timber and other forest products and to other services.

Clearly, much remains to be done in formulating and implementing national policies with respect to the public's stake and responsibilities in private forestry; in providing effective protection against fire and other hazards; in making readily available the technical know-how and essential on-the-ground management services; in helping private owners to overcome the handicaps of small-scale operation, unfamiliarity with technical forestry methods, and difficulty in financing forest enterprises; and in strengthening and enlarging public forests.

These are the issues to be met. For the Nation needs productive forests. Timber is a basic and indispensable natural resource—an important part of America's great industrial strength. But our timber supply is running dangerously low. We are overdrawing our forest bank account and new growth is falling far short of prospective requirements. A much stronger program of forestry is needed to assure timber for the future and to care for the expanding needs of watershed protection, forest recreation, and other forest uses. If the United States is to maintain a place of economic leadership in the world of tomorrow, it can ill afford to temporize with its forests.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

misc-668/sec12.htm Last Updated: 17-Mar-2010 |