|

TREES OF THE FOREST: Their Beauty and Use |

|

Great Trees of the American Forest

Douglas-fir, ponderosa and southern pines, yellow-poplar, sugar maple, and the white oak are great American trees, beauties on the landscape wherever they stand. As forest trees, they are grown to serve many useful purposes. You can derive more enjoyment from your travels through the National Forests by observing these and other species and learning why each grows best in its particular environment.

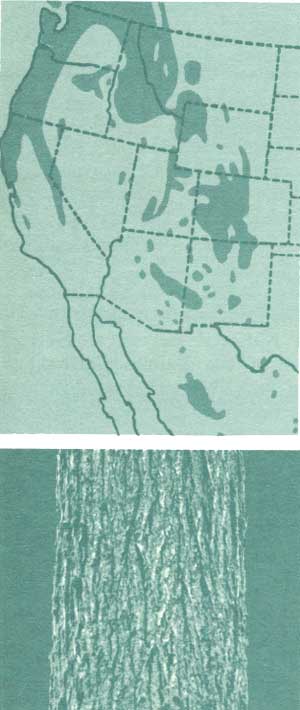

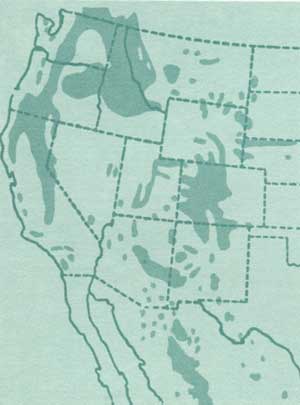

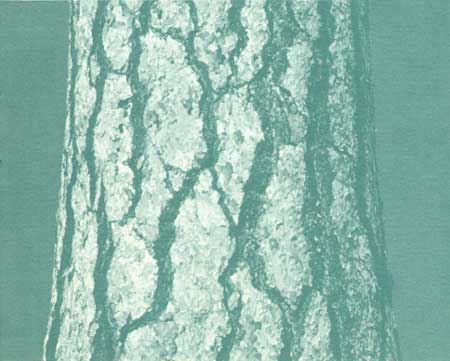

Douglas-Fir, the State tree of Oregon, produces more wood products than any other American tree and perhaps is the world's most valuable species of conifer. It grows in moist forests from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific coast, reaching its largest size on the western slopes of the Cascade Mountains and along the northwest coast, where soil is rich and moisture plentiful. Douglas-fir grows second in size only to the California sequoias, giant sequoia and redwood (Sequoia gigantea and Sequoia sempervirens), with heights of 200 feet or more and diameters of 3 to 6 feet. Under favorable conditions individual trees may live a thousand years, grow 10 feet through and 300 feet tall, with furrowed, cinnamon-brown bark 1 foot thick.

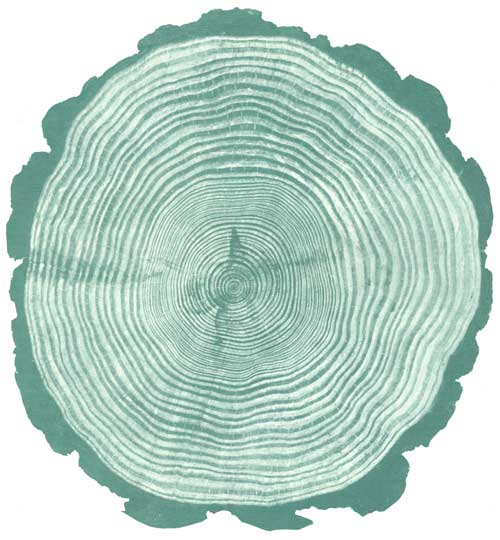

Douglas-fir scatters its seed prolifically (with an average of 42,000 seeds per pound taken over its entire range; California has 30,000-35,000, British Columbia 49,000) and young trees grow fast and dense in the mineral soil of the Northwest. At 10 years they are 15 feet high, and in 25 years are twice as tall with sometimes as many as 1,000 trees to the acre. As they grow, the forest thins naturally; in a century the trees can reach 200 feet in height and may then number about 115 to the acre.

Small trees are hardy and attractive for ornamental planting. With their soft, rich green needles hanging on long after cutting, they are also beautiful and popular Christmas trees.

The wood, yellowish to light red in color, is strong for its fairly light weight, and is resistant to decay. The size of the tree permits the manufacture of lumber remarkably free of knots and other defects, with pieces 60 feet long by 2 feet square. The softwood veneer and plywood industries depend almost entirely on Douglas-fir for raw materials. Recently new uses (fiberboard, book paper, wrapping paper) have been developed for sawmill leftovers.

For years this unique conifer was a botanical puzzler, having been called spruce, hemlock, balsam fir, and even pine. The scientific name meaning false hemlock (Pseudotsuga menziesii) honors Dr. Archibald Menzies, physician and naturalist with Captain Vancouver's voyage, who discovered this tree on the Pacific coast in 1791. It remained for the roving Scotch botanical collector David Douglas to send the first seeds to Europe in 1827. Soft, deep yellow-green or blue-green needles about an inch long, flattened and pointed, grow all around the twig. The oval cone with distinctive three-pronged bracts hangs like a pendant.

Ponderosa Pine, a beautiful and hardy tree, grows in every State west of the Great Plains, and is the State tree of Montana. It has a total stand greater than any native tree species except Douglas-fir, and reaches maximum growth in the resin-scented Sierra forests of California: over 200 feet in height, 5 to 8 feet in diameter, 500 years in age.

During its early life ponderosa pine bark is dark brown, nearly black, which prompts the local names "blackjack" and "bull pine." Then it becomes plated and scaly, turning distinctive cinnamon-brown to orange-yellow. Bluish-green needles, 4 to 7 inches long, grow in clusters of three or sometimes two. The brown cones are clustered too, standing erect on small stalks and growing 3 to 6 inches long. Like most other pines, the ponderosa's cones require two seasons to mature.

Ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) is the most valuable and extensive timber tree of the Southwest, ranging in a 300-mile belt from the Gila National Forest of New Mexico to the Kaibab Plateau of the Kaibab National Forest in Arizona. It grows just above the sagebrush and pinyon-juniper woodland, requiring less water than most other commercial trees. Tenaciously the seedling withstands drought, often surviving on only the dew of night. A year-old tree will sink its roots 2 feet deep in quest of water, a 4-year-old tree more than twice as deep. In many places on these southwestern forest lands, as many as 6,000 to 10,000 young ponderosa pines stand congested on a single acre, competing for water, soil nutrients, and light.

At its best the ponderosa pine, rising to a broad, conical crown, makes a handsome ornamental tree. It also makes hard, strong, and fine-grained wood. High-grade ponderosa is used for doors, sashes, frames, and paneling; the low-grade wood for boxes, rafters, joists, and railroad ties.

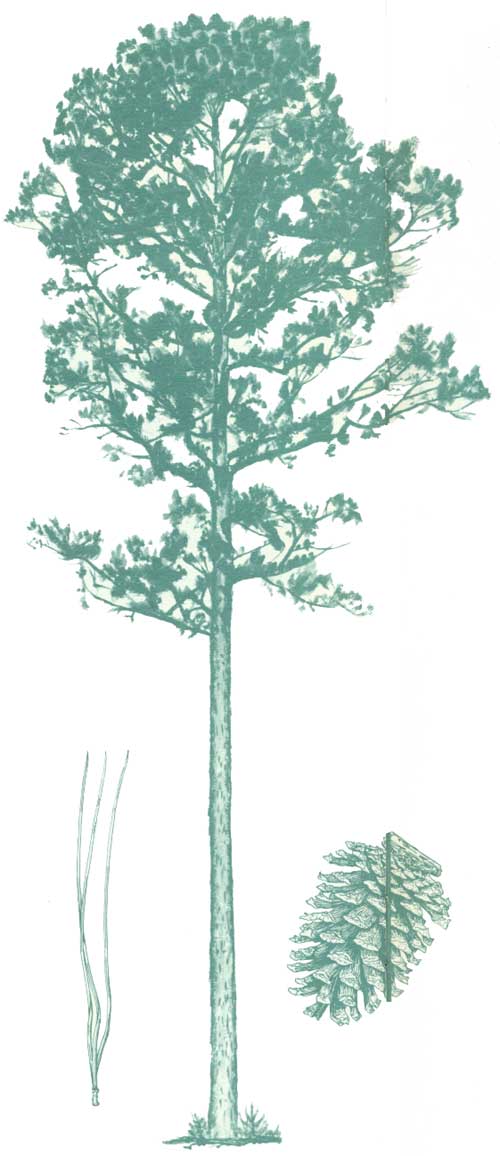

Southern Pines are now recognized as a vast, important source for the Nation's future timber supply. An indication of the South's role in forestry is the fact that it produces fully 80 percent of all forest tree seedlings grown in the United States. The pine is the State tree for both Alabama and Arkansas.

The most plentiful southern pine, loblolly (Pinus taeda), often grows in moist depressions which in the early days were known as "loblollies." Its needles are borne three in a cluster and grow 6 to 9 inches long. This rapidly growing tree develops a clean, straight trunk, reaches maturity in about 70 years, and sometimes yields 20,000 to 30,000 board feet of timber per acre. Slash pine (Pinus elliottii) is a beautiful tree of the Coastal Plain with lustrous dark green needles, usually three in a cluster and 8 to 12 inches long, and a purplish-brown bark. The two other major southern pines are shortleaf (Pinus echinata), with slender bluish-green needles 5 inches long or less, two or three in a cluster, and longleaf (Pinus palustris), with tapering trunks up to 120 feet in height, and dark green needles three in a cluster, 10 to 15 inches and sometimes 18 inches long. Longleaf and slash pines are the principal sources of turpentine and rosin, known as naval stores because of their early use in caulking wooden ships. Six other species of pines are native in the South. The southern pines have a variety of other uses, notably for paper pulp, housebuilding materials, fuel, and general millwork.

Yellow-Poplar, or tuliptree, distinguished by its excellent form and rapid growth, is one of the tallest and most valuable hardwoods in the United States. Widely distributed through the Eastern States, it grows in sheltered coves of the Appalachians in stands mixed with other large broadleaf trees and an understory of dogwood, azalea, rhododendron, and many wild flowers. It is the State tree of Indiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee. The yellow-poplar reaches heights of 80 to 120 feet (maximum recorded 198 feet) and diameters of 2 to 6 feet, with its straight, deeply furrowed trunk clear of limbs for much of its length. It may live 250 years or more.

Hardly any American tree has a richer tradition than the yellow-poplar. "Everyone," wrote William Byrd, in his early Natural History of Virginia, "has some of these trees in his gardens and around the house, for ornament and pleasure." Indians and settlers made dugouts of it. The Delaware Swedes called it the "canoe tree." George Washington, who had an astonishing knowledge of many trees and their uses, planted yellow-poplars at Mount Vernon. Two of them, nearly 120 feet tall, still vigorous and growing, are now the tallest trees at this great estate.

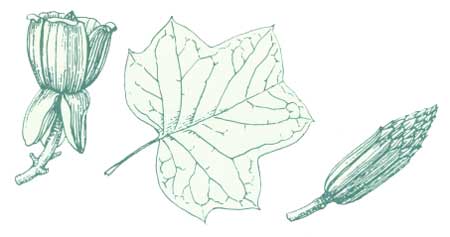

Though called yellow-poplar, because of its light-colored softwood, it is really a member of the magnolia family and bears the scientific name Liriodendron tulipifera, "lily tree bearing tulips." Its large flowers, a blend of green and yellow tinged with orange, are among the early spring arrivals in the forest, a welcome source of nectar to honeybees. The blossoms emerge above a background of long-stemmed, glossy, notched leaves that tremble in the slightest breeze. The flowers develop into dry, cone-like fruit, from which winged seeds fall twirling to the ground.

Young trees shoot toward the light and, in some of the best stands, grow 50 feet in 10 years. The twigs and branches of very small yellow-poplars are tasty to deer, which sometimes cause extensive damage.

With its attractive flowers, foliage, and symmetrical form, the yellow-poplar is frequently adapted for shade and ornamentation. The straight-grained wood of yellow-poplar is used in furniture and woodware, for veneer, and in construction. Its importance as a lumber tree has increased immensely since the tragic loss of the once great forests of chestnut. (Many foresters regarded the chestnut as the finest hardwood tree in America before it fell victim to a relentless blight, a fungus introduced from Asia.) Its nuts were a food staple of squirrels, turkeys, bears, and other animals, all of which have suffered since the passing of the chestnut. No remedy has been found for the blight, but Forest Service researchers have been encouraged recently in their efforts to breed a blight-resistant chestnut.

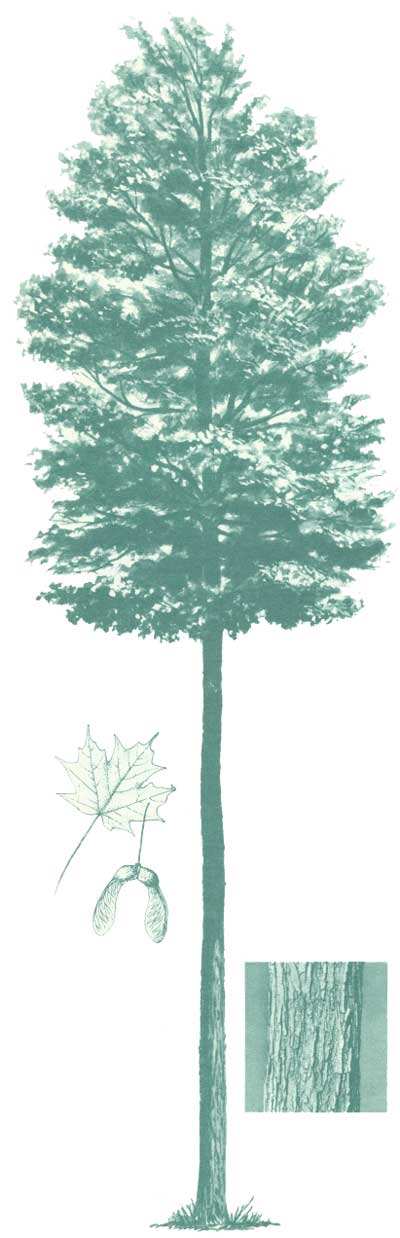

Sugar Maple, the most abundant and versatile of all the maples, the showy beauty of the autumn landscape, is notable as the source of fine hardwood lumber and maple sirup. It is found in nearly every State east of the Great Plains, with its largest stands, usually mixed with other hardwoods, in the Lake States and New England. Sugar maple grows slowly but lives 300 to 400 years, reaching heights of 80 to 120 feet. It is the State tree of New York, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wisconsin.

The apt scientific name, Acer saccharum, refers to the sweetness of the sap, from which maple sirup and sugar are boiled when winter is on the wane. Like the sugarcane and sugarbeet, this maple is characterized by an unusually high concentration of sugar, produced the year before and stored in roots and trunk during the dormancy of winter. With leaf buds swelling and the imminence of spring, the sap rises and is tapped just inside the bark by driving in a spout and attaching a tube or hanging a bucket beneath it. In this sturdy, stately tree, tapping may go on for years without seriously affecting the life of the tree or the quality of its wood. In spring, after the sugaring-off season, the maple sends forth myriads of greenish-yellow clustered flowers from which bees obtain pollen and nectar. In early summer seeds mature and fall to the ground on papery wings. Later, in autumn, sugar residue in heart-shaped thin leaves combines chemically with other substances to produce the most striking orange-yellows and reds of the hardwood landscape.

Maple has been a choice wood since the time of the Romans, who used it for their pikes and lances as well as furniture. Known to the lumber trade as hard maple, the strong, close-grained wood makes firm flooring, lustrous furniture, bowling alleys and pins, and musical instruments. Accidental forms known as curly maple and birdseye maple are prized for fancy-figured furniture and cabinets.

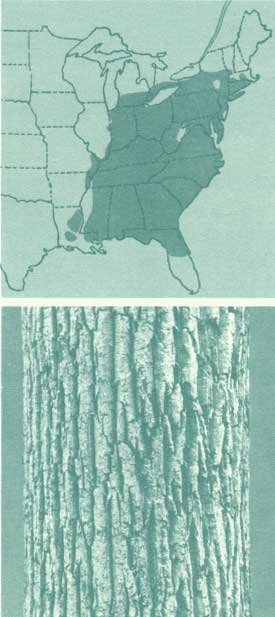

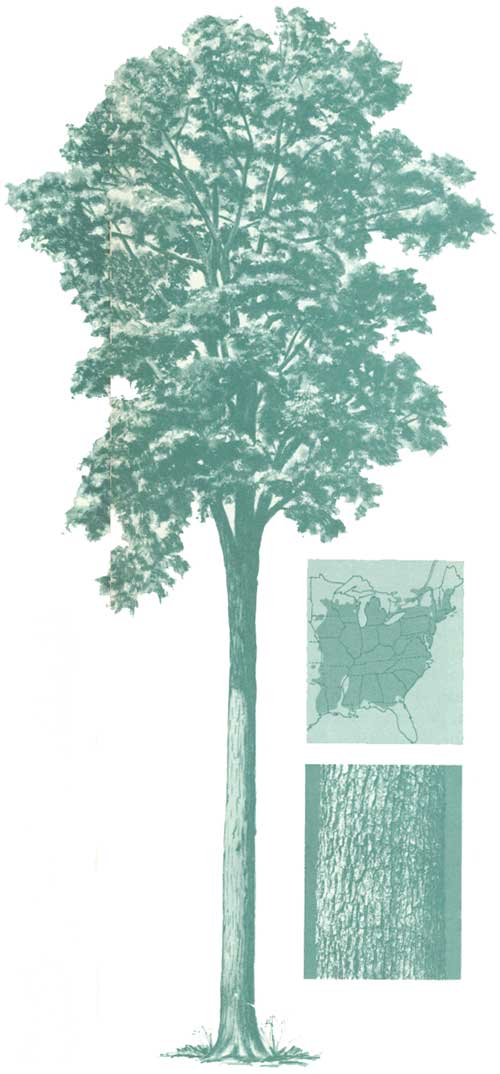

White Oak has been known and loved since the earliest days of settlement in the New World. It reminded the colonists of the English oak—and the Indians showed how to boil and eat its large acorns. White oak grows from New England south to Florida, through the Middle West to the Lake States, and as far west as Oklahoma and Texas. It is the State tree of Connecticut and Maryland, while "native oak" is the State tree of Illinois.

This tall, broad-crowned tree reaches heights of 80 to 100 feet (maximum, 150 feet), with diameters of 3 to 6 feet. Its whitish or pale gray bark is decidedly lighter in color than that of the black (or red) oak group. Its scientific name Quercus alba includes the classic Latin generic name for all oaks, Quereus, and alba (white), applied by the famous botanist Linnaeus.

The large leaves are formed with five to nine rounded lobes and, unlike the black oaks, have no bristles. The deep somber brown, or russet, of the oak leaf is a familiar feature of the autumn landscape, and on young trees many dead leaves remain attached throughout the winter. Acorns, the seed of the oak, mature in early autumn. These shiny brown, sweet-flavored nuts, known as mast, have become an important food for bears, squirrels, and birds, particularly with the passing of the chestnut.

The oak grows slowly but lives long, sometimes 500 to 600 years. In open fields or lawns the trunk is shorter and the branches spread outward 80 feet or more. In the forest, white oak grows best in deep humus soil and is found in a mixture with other oaks, hickory, and maple.

Of the more than 20 species of commercially important Eastern oak, white oak is truly outstanding. From the earliest days it provided a valuable source of timber for houses, ships, and furniture. Strength, durability, and beauty are the words for white oak. Its uses range from barrels and bridges to flooring and fine cabinets.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

PA-613/sec4.htm Last Updated: 12-Sep-2011 |