|

A PRIMER OF FORESTRY PART II—PRACTICAL FORESTRY |

|

CHAPTER I.

THE PRACTICE OF FORESTRY.

THE SERVICE OF THE FOREST.

Next to the earth itself the forest is the most useful servant of man. Not only does it sustain and regulate the streams, moderate the winds, and beautify the land, but it also supplies wood, the most widely used of all materials. Its uses are numberless, and the demands which are made upon it by mankind are numberless also. It is essential to the well-being of mankind that these demands should be met. They must be met steadily, fully, and at the right time if the forest is to give its best service. The object of practical forestry is precisely to make the forest render its best service to man in such a way as to increase rather than to diminish its usefulness in the future. Forest management and conservative lumbering are other names for practical forestry. Under whatever name it may be known, practical forestry means both the use and preservation of the forest.

THE USES OF THE FOREST.

|

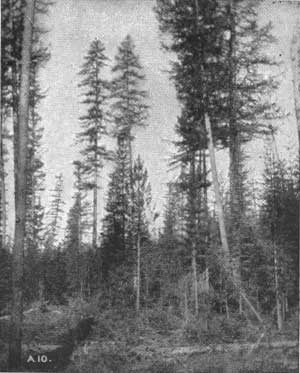

| Fig. 1.—Alpine hemlock in a protection forest. Cascade Mountains, Washington. |

A forest, large or small, may render its service in many ways. It may reach its highest usefulness by standing as a safeguard against floods, winds, snow slides, moving sands, or especially against the dearth of water in the streams. A forest used in this way is called a protection forest, and is usually found in the mountains, or on bleak, open plains, or by the sea. Forests which protect the headwaters of streams used for irrigation, and many of the larger windbreaks of the Western plains, are protection forests. The Adirondack and Catskill woodlands were regarded as protection forests by the people of the State of New York when they forbade, in the constitution of 1895, the felling, destruction, or removal of any trees from the State Forest Preserve.

A farmer living directly on the produce of his land would find his woodlot most useful to him when it supplied the largest amount of wood for his peculiar needs, or the best grazing for his cattle. A railroad holding land which it did not wish to sell would perhaps find it most useful when it produced the greatest number of ties and bridge timbers. In both cases the forest would render its best service by producing the greatest quantity of valuable material. This is the central idea upon which the national forests of France are managed.

The greatest return in money may be the service most desired of the forest. If a farmer wished to sell the product of his woodlot instead of consuming it himself, his woodland would be useful to him just in proportion to its net yield in money. This is true also in the case of any owner of a forest who wishes to dispose of its product, but who can not, or will not, sell the forest itself. State forests, like those in the Adirondacks, often render their best service, in addition to their usefulness as protection forests, by producing the greatest net money return.

|

|

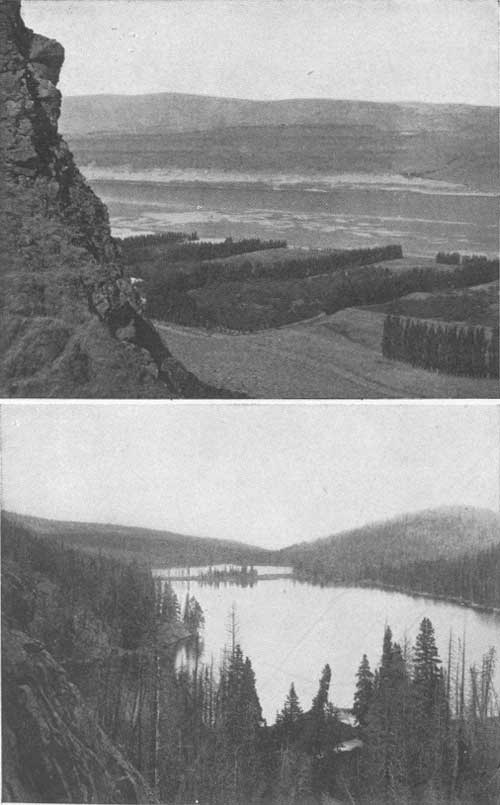

Plate II. FIG. 1.—WINDBREAKS OF LOMBARDY POPLAR, INTENDED TO

PROTECT ORCHARD TREES AGAINST WIND AND MOVING SAND. NEAR THE DALLES,

OREGON. FIG. 2.—PROTECTION FOREST ABOUT A LAKE. ADIRONDACK MOUNTAINS, NEW YORK. |

|

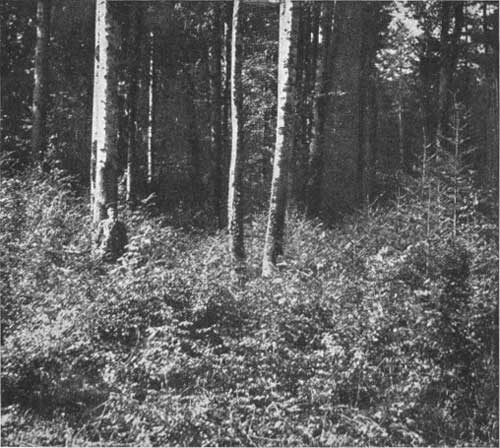

| Plate III. SCENE IN THE SIHLWALD, THE TOWN FOREST OF ZURICH, SWITZERLAND, FROM WHICH ITS OWNER DESIRES THE GREATEST NET MONEY RETURN. |

|

| Fig. 2.—Moving sand dunes near Cape May, N. J., where once the whaling town of Portsmouth stood. In the foreground, red cedars buried and partly uncovered by the wind. |

Regarded as an investment of capital, a forest is most useful when it yields the highest rate of interest. A forest whose owner could sell it if he chose, but prefers to hold it as productive capital, is useful in proportion to the interest it yields on the money invested in it. Thus, an acre of spout land may be worth only $5, while the investment in adjoining land stocked with old trees may be $50 an acre. This is the view which controls the management of State forests in Germany. Lumbermen also regard timberland as an investment, but usually they take no care except for the yield at the moment. They disregard the future yield altogether, and in consequence the forest loses its capital value, or may even be totally destroyed. Well managed forests, on the other hand, are made to yield their service always without endangering the future yield, and usually to its great advantage. Like the plant of a successful manufacturer, a forest should increase in productiveness and value year by year.

|

| Fig. 3.—An exceedingly productive spruce forest in Bavaria. |

Under various circumstances, then, a forest may yield its best return in protection, in wood, grass, or other forest products, in money, or in interest on the capital it represents. But whichever of these ways of using the forest may be chosen in any given case, the fundamental idea in forestry is that of perpetuation by wise use; that is, of making the forest yield the best service possible at the present in such a way that its usefulness in the future will not be diminished, but rather increased.

FOUR REQUIREMENTS FOR THE BEST SERVICE.

A forest well managed under the methods of practical forestry will yield a return in one of the ways just mentioned. There are, however, four things a forest must have before it can be in condition to render the best service.

The first of these is protection, especially against fire, overgrazing, and thieves, for without such protection no investment is secure and the most skillful management is of little effect.

The second is strong and abundant reproduction. A forest without young growth is like a family without children. It will speedily die out.

|

| Fig. 4.—Vigorous reproduction along the edge of a forest. Germany. |

|

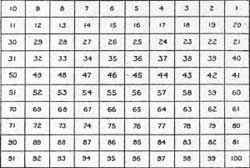

| Fig. 5.—Diagram of a forest with one hundred even-aged compartments. |

The third requirement is a regular supply of trees ripe for the ax. This can be secured only by the right proportion of each of the smaller sizes constantly coming on in the growing forest. Thus, a farmer in need of fuel might be much inconvenienced to find no trees on his woodlot big enough for cordwood, and it would not help him to know that twenty years later he would have an oversupply. In the same way a larger forest may yield only a very irregular and unsatisfactory product if at one time there are too many ripe trees and at another too few. For example, if 100 acres become fit to cut this year, and 200 next year, and after that none at all until 500 acres become ripe fifteen years later, it is easy to see that the yield would come at very irregular and perhaps very inconvenient times. But a forest of 10,000 acres, composed of 100 even-aged groups of trees of every age from 1 to 100 years, each group 100 acres in extent (see fig. 5), would plainly be able to furnish every year 100 acres of 100-year-old trees ready for the ax. In such a forest the right proportion of young trees would always be coming on.

|

| Fig. 6.—A white cedar which has had too much growing space. The tree is large, but full of knots, and will yield very little good lumber. |

The fourth requirement is growing space enough for every tree, so that the forest as a whole may not only produce wood as fast as possible, but the most valuable sort of wood as well. If the trees stand too far apart, their trunks will be short and thickly covered with branches, the lumber cut from them will be full of knots, and its value will be small. If, on the other hand, the trees stand too closely together, although their trunks will be tall and clear of branches, they will be small in diameter, and for that reason low in value. With the right amount of growing space, trees grow both tall and of good diameter, and their trunks supply lumber of higher price because it is wide and clear.

THE YIELD OF A FOREST.

|

| Fig. 7.—Old trees which have had the right amount of growing space to make clean trunks and clear lumber. Germany. |

One of the central ideas of forestry is that the amount of wood taken from any healthy forest and the amount grown by it should be as nearly equal as possible. If more grows than is cut, then the forest will be filled with over mature, decaying trees; but if more wood is cut than is grown, then the supply of ripe trees will be exhausted, and the value of the forest will decline. To make the cut equal to the growth does not mean that the volume of wood grown each year on every acre should be cut from that acre, but that the total growth of all the acres, for one or for a number of years, should be cut from the forest in the corresponding period. Thus, if the growth or increase is 100 cords a year, that amount might be harvested yearly by cutting every tree on a small area, by cutting fewer trees per acre on a larger area, by distributing the cut every year over the whole surface of the forest, or by cutting 1,000 cords in any one of these ways once in ten years.

There are many different methods of finding what is the annual increase of wood in a forest. One of the simplest is to count the number of trees upon an acre and select an average tree, then to cut it down, measure its cubic contents, and find its age by counting the annual rings. That done, the yearly increase of the average tree may be found by dividing its cubic contents by the years of its age. Finally, since we have found the yearly increase per tree and the number of trees per acre, it is easy to find the average yearly increase per acre. It is unfortunate that this simple and easy process is not always reliable, because it is hard to find either an average acre or an average tree.

|

| Fig. 8.—Measuring an average tree. Adirondack Mountains, New York. |

The yield of a forest is the amount of wood that is taken from it in a given time. When a forest is put under conservative management, one of the most important steps is to decide how much timber can safely be taken from it; in other words, to determine the yield. There are three principal ways of doing so.

The first, and the least used, is to fix the yield at a certain number of mature trees. By this plan the yield of a certain forest might be 100 pines, 260 spruces, and 180 hemlocks, each of a given diameter, every year.

The second way is to fix the yield at a certain amount or volume of wood. Thus, the yield of a large forest might be fixed at 25,000,000 feet board measure every ten years, and that of another smaller one at 750 cords every year.

The third way is to settle upon a certain number of acres to be cut over yearly or once in a given number of years. By this method the yield of a forest of 600 acres might be fixed at 6 acres of mature timber a year, and that of another at 300 acres every twenty-five years. The time between two successive cuttings on the same area must be long enough to allow the young trees left standing to mature. That time if found by studying the rate of growth in diameter.

This method of determining the yield by area is much the most practicable of the three for the forests of the United States, and in general it is the simplest and most widely useful of all, because it does away with the difficult task of determining the yearly increase in wood.

|

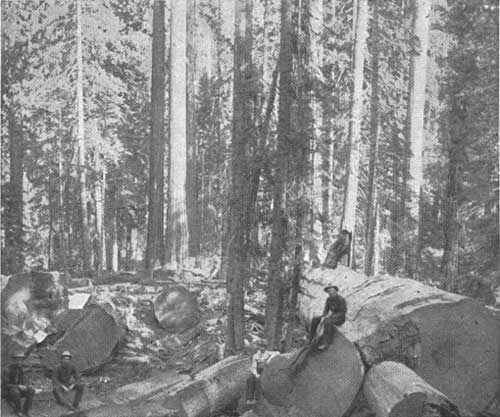

| Fig. 9.—A forest from which more than the yield is being taken. Big Trees in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, California. |

The objects in handling forests are so various that sometimes no single one of these methods is satisfactory, and then combinations of them are of great use. Thus, by combining the method by volume and the method by area the annual yield of a forest might be established at 250 board feet per acre. This yield might be cut from the forest every year, or it might be allowed to accumulate for twenty years, and then 5,000 board feet per acre might be cut.

|

|

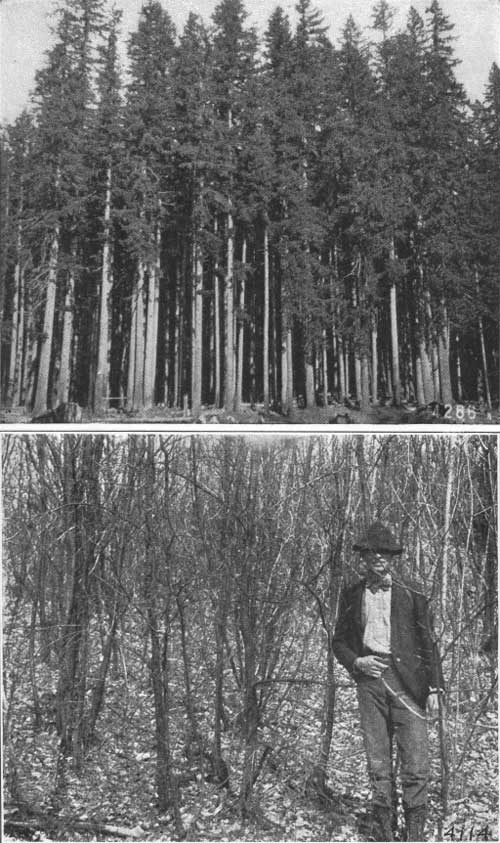

Plate IV. FIG. 1.—SEED FOREST OF FIR IN WASHINGTON. FIG. 2.—SPROUT FOREST SPRINGING UP AFTER A FIRE. |

SILVICULTURAL SYSTEMS.

After the yield has been found it must be cut not only without injury to the future value of the forest, but in such a way as to increase its safety and usefulness. To this end certain ways of handling forests, called silvicultural systems, have grown up. They are based on the nature of the forest itself, and are chiefly imitations of what men have seen happen in the forest without their help.

From the point of view of forest management, one of the principal differences between trees is whether they spring directly from seed or are produced as sprouts from stumps or roots already in the ground. A forest composed of seedling trees is called a Seed Forest, or more commonly but less suitably, a Seedling or High Forest. One composed of sprouts is spoken of as a Sprout or Coppice Forest, or, more often, simply as Coppice, or as Sprout land. Seed Forests are usually composed of coniferous trees, which rarely sprout, or of broadleaf trees allowed to reach large size. Sprout Forests are common wherever broadleaf trees are cut while they are still young, for the sprouting power usually diminishes with age. Sprouts never reach so great a height and diameter as seedling trees, although in youth they grow much faster; and they are apt to be unsound, because the old stumps decay and infect the sprouts which spring from them.

SIMPLE COPPICE.

It often happens, as in Pennsylvania or New Jersey, that a fire sweeps over the second-growth hardwood lands and kills all the young trees down to the ground; but the roots remain alive, and from them spring young sprouts about the bases of the burned trunks. After several years a second fire may follow and kill back the sprouts again, and other fires may continue at intervals to burn over the land, each followed by a new crop of sprouts. When a farmer does with the ax what is often done by fire he is using the system of Simple Coppice. Let us suppose a farmer has a woodlot covered principally with chestnut sprouts which he wants to manage for the steady production of railroad ties. He knows that chestnut sprouts are usually large enough for ties at the age of 35 years. In order to insure a steady yield of trees fit for ties, he divides the whole woodlot into thirty-five parts of equal productive capacity, and cuts one part clean every year. All the new sprouts that spring up on the part cut in any year are of the same age. At the end of thirty-five years, when the whole woodlot has been cut over, the thirty-five parts form a series of even-aged groups of sprouts from 1 to 35 years old. Every year the sprouts on one part reach the age of 35 years and are ready for cutting.

|

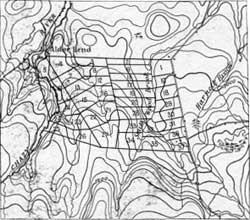

| Fig. 10.—Ideal sketch map of a sprout forest managed under the system of Simple Coppice. |

Simple Coppice is a very useful silvicultural system, and the easiest of all to apply. The chief requirements for its success are good reproduction from the stumps, proper thinning (where thinning can be made to pay), and enough young seedlings among the sprouts to replace exhausted stumps with vigorous young ones. Stumps from which the sprouts have been cut many times finally grow weak and lose their power of sprouting.

In cutting sprouts it is important not to loosen the bark on the stumps, for that impairs their sprouting power, and to make the cut as near the ground as possible. Stumps cut level with the surface sprout best of all. In Simple Coppice, well handled, the reproduction takes place of itself without the need of further attention from the forester.

Many thousands of acres of American woodland, especially in New England, New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, and in other places where chestnut is the principal tree, are treated under a rough system of Simple Coppice.

|

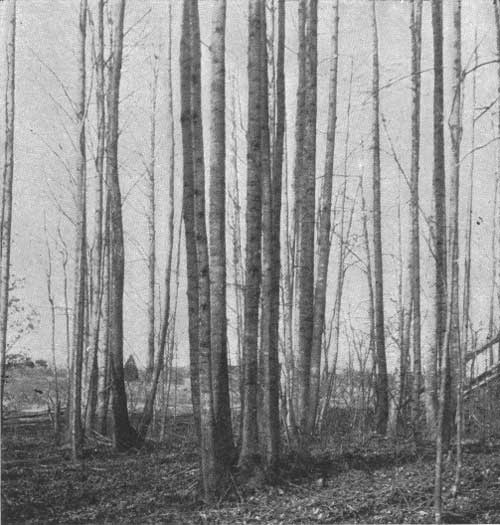

| Fig. 11.—Yellow poplar sprout forest in Maryland. |

STORED COPPICE.

Among the trees which will produce only fuel, fence posts, or railroad ties there often stand in a woodlot others which would yield much larger returns if they were allowed to reach a greater age and size than the trees about them. If there were some white oaks scattered through the chestnut coppice just described, it might be well to let them grow large enough for the production of high-priced material like quartered oak lumber. In that case it would be necessary at the time of cutting the sprouts to select and leave standing a certain number of white oaks on every acre. As many of them as survived the increased exposure to wind and sun following the sudden removal of their neighbors would remain as standards over the young sprouts. The white oak standards thus chosen would remain uncut during two, three, four, or sometimes even five successive crops of sprouts, and would form stout trunks with little taper, clear of branches almost to the full height reached by the sprouts.

This is the silvicultural system called Stored Coppice, or sometimes Coppice under Standards. The successful management of a forest under it depends largely upon the choice of the standards. They should be seedlings, for seedlings make the best trees, or the most vigorous and healthy sprouts if seedlings can not be found, and they should be distributed as regularly as possible over the ground. The standards should be numerous enough at first to allow for heavy loss from wind and shock when the sprouts are cut away, but they should never be allowed to suppress the lower story of growth.

Stored Coppice is a very useful system where the principal demand is for small material, like fuel, ties, and fencing, but where some large timber also is required. It was developed chiefly by the French, who use it with admirable results.

|

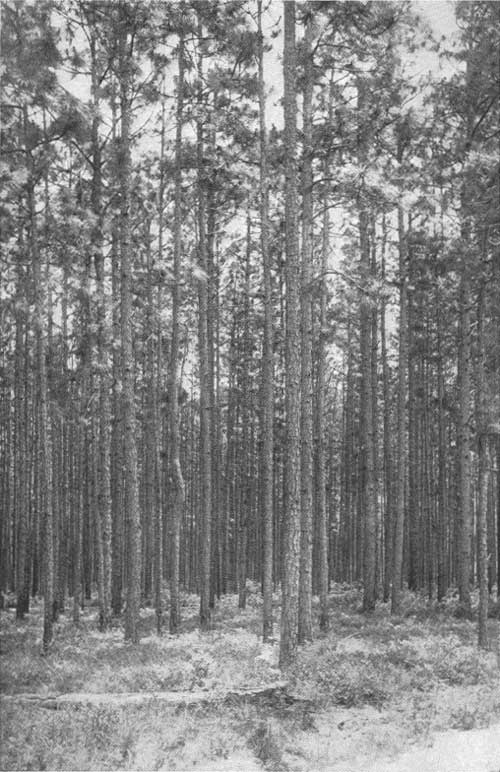

| Plate 5. SEED FOREST OF LONGLEAF PINE IN FLORIDA. |

SEED OR HIGH FOREST.

By far the most useful and important forests are, as a rule, those which spring directly from seed, such as the pine forests of the Southern States, and the great hardwood forests of the Mississippi Valley. Such forests are called Seed Forests. The Seed forest systems are of many kinds, some of which are peculiarly adapted for the management of certain forests in the United States. Just as the Sprout Forest systems are chiefly useful to produce fuel, posts, ties, and trees of small size, so the Seed Forest systems are produces of sawlogs and large timbers.

|

| Fig. 12.—Seed forest of lodgepole pine in Idaho. |

REGULAR SEED FOREST.

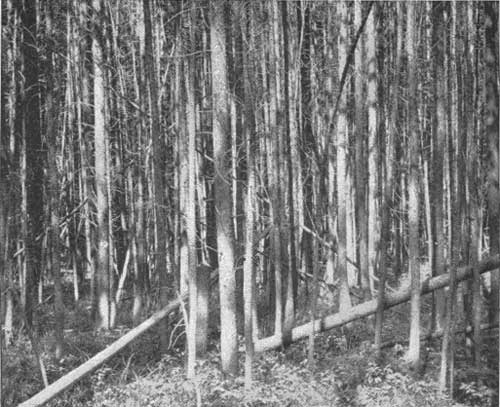

When a tract of woodland is destroyed by fire in one of the Rocky Mountain States, it often happens that the seeds of the lodgepole pine are scattered over it by the wind in prodigious numbers. The seeds germinate abundantly, seedlings spring up, and in a very few years a young even-aged forest of lodgepole pine covers the ground. As it grows older fires destroy patches of it here and there, and in time every patch is covered again with a younger generation of even age. After many years the forest which sprang up after the first fire has become broken into a number of even-aged patches without uniformity in size or regular gradations in age.

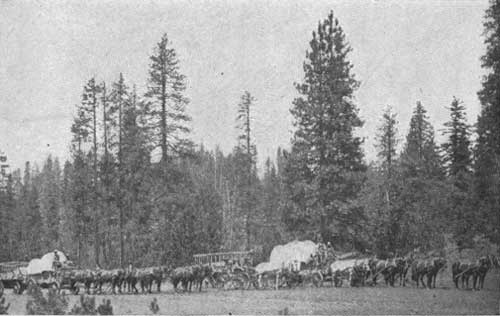

Now let us suppose that this land was taken in hand by the Government when the lodgepole pine first came in, and that the lodgepole reaches its maturity at 80 years. If the Government forest officers had divided such a forest into eighty parts, and then had cut the timber from one part each year, after a time they would have had eighty divisions, each covered with even-aged forest, but differing in age among themselves from 1 to 80 years. Every year one part would reach the age of 80 years and would be cut, and evidently the other seventy-nine parts would always be stocked with trees from 1 to 79 years old.

|

| Plate VI. DIAGRAM TO REPRESENT THE PROGRESS OF CUTTING IN REGULAR SEED FOREST. Each tree represents one even-aged division. Only one division in ten is represented. |

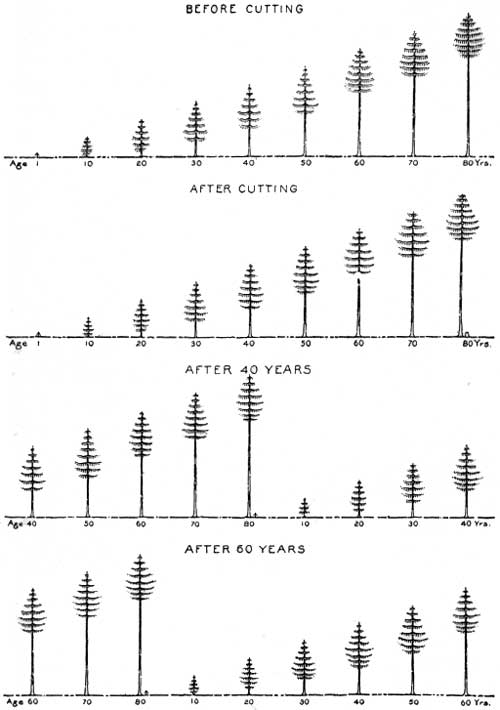

When the trees on one of the eighty divisions just mentioned become ripe for the ax, provision must be made for a new crop. This would be a very simple matter if the forest on that division could be reproduced naturally in one year, but that is practically impossible. Such rapid reproduction can be got only by planting, which is chiefly useful in the United States for making new forests and restoring injured forests, not for renewing old ones. Reproduction from the seed of the old trees is the only kind we need consider here. In order to bring it about a few ripe trees are first cut down, to prepare a seedbed by giving light to the soil, and to fit the seed trees to bear more abundantly by giving the crowns more room. Then, when a good crop of seed is likely to appear, a few more trees are removed to give the future seedlings light enough for healthy growth, but not enough to expose them to danger from frost, drought, or the choking of grass and weeds, for young trees just starting in life are very sensitive and easily destroyed. Finally, as the young trees grow taller and stronger, what remains of the old crop is gradually cut away. When it is all gone, usually from ten to twenty years have passed since the reproduction cuttings were begun.

|

| FIg. 13.—Mixed forest in process of gradual reproduction. Sihlwald, Switzerland. |

This is the system of Regular Seed Forest. It is difficult to apply, and unsafe except in experienced hands. It has often been necessary to plant large areas at great expense because reproduction cuttings in Regular Seed Forest have failed. The transportation of the timber is frequently expensive, because it must be spread over a number of years. On the other hand, when it is well applied this system produces the highest type of forest, full of tall straight trunks clear of branches, and consequently yields a high grade of timber and a large return in money.

|

| Fig. 14.—Reproduction obtained by process shown in fig. 13. Sihlwald, Switzerland. |

TWO-STORIED SEED FOREST.

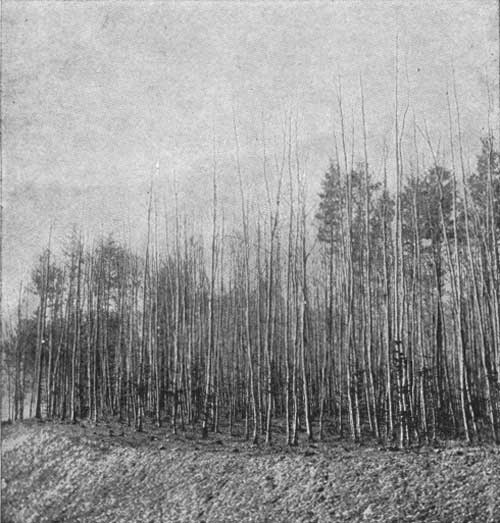

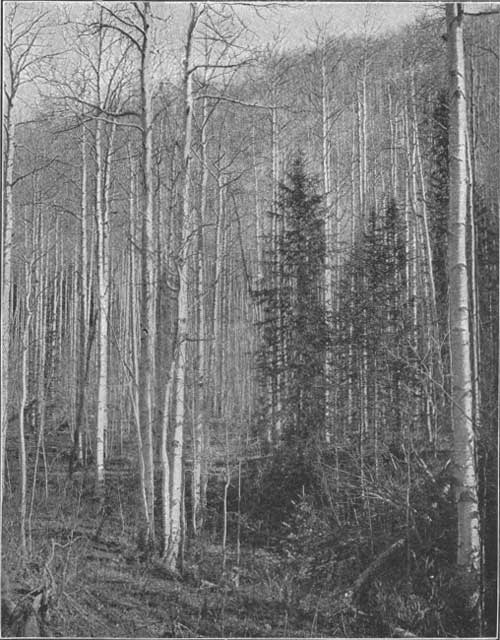

After a forest fire in Maine it frequently happens that the first tree to cover the ground is the popple, or quaking aspen. It is a slender, short-lived tree, intolerant of shade, with a light crown. After the popple has grown for some years, spruce seedlings spring up under the friendly cover, and rapidly follow the popple in height. There grows up in this way a forest composed of an upper and a lower story of growth, in which, as so often happens, the lower story is of more importance.

The system of Two-Storied Seed Forest is useful when a tolerant tree like the spruce is to be grown under the shade of an intolerant tree like the aspen. In countries where forestry is well developed it is usually to plant young trees of tolerant species under older intolerant trees, to make a acre for the soil and to prevent the growth of grass and weeds. Forests which closely resemble two-storied seed forests are common in the United States, but usually as the result of fire or careless cutting. Such are, for example, the forests of pine over oak in the southeastern United States, and of birch, beech, and maple under white pine in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. It often happens, as in the case of the spruce and aspen, that both stories can not live on in good health together, and that the upper one must die or be cut away if the lower is to prosper.

|

| Fig. 15.—Young growth of spruce under older growth of popple. Colorado. |

SELECTION FOREST.

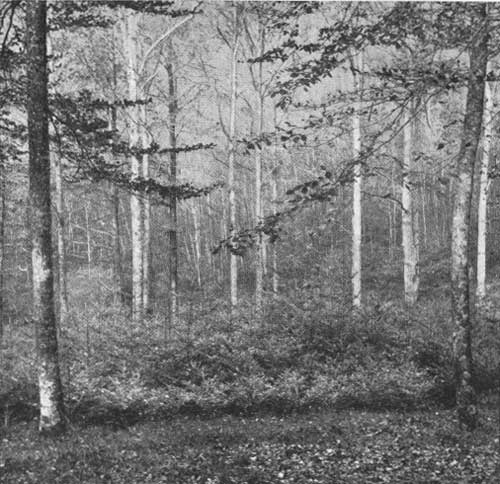

When a stand of aspen dies away from a young crop of spruce, the ground is no longer completely shaded, and there is light and room for other kinds of trees to come in. Thus, birch and maple seeds may be blown in by the wind and beechnuts carried and planted by squirrels, and eventually the pure stand of spruce is changed into a mixed forest of various ages. As the trees grow older, some of the spruce may be destroyed by beetles or thrown by the wind, and some of the broadleaf trees may die from fungous disease. Into the openings made by the death of older members of the forest fall the seeds from which younger members spring. So little by little the forest loses its even-aged character and there comes into existence what is called a Natural or Selection Forest, in which trees of all ages are everywhere closely mixed together. Most virgin forests are selection forests.

|

| Plate VII. MIXED SELECTION FOREST IN THE SOUTHERN APPALACHIANS. |

|

| Fig. 16.—Lodgepole pine and western larch in selection forest. Northern Idaho. |

|

| Fig. 17.—Mimic pure selection forest, showing the mixture of ages. |

The silvicultural system called Pure Selection is applied to forests of this kind. It is used chiefly for protection forests in places where it is desirable to keep the cover always unbroken; elsewhere it is out of place. Under this system the annual increase of the forest must be found before the yield can be determined. Then the fully mature trees are cut in every part of the forest every year. The cost of logging is high, for where single trees are taken here and there, roads or other means of transport must be very numerous and costly in proportion to the amount of the cut.

LOCALIZED SELECTION.

Logging under the system just mentioned is so expensive as to prevent its application in the United States, except for woods like cherry and black walnut, which have a special and unusual value. But if, instead of taking the yield from every part of a selection forest, a comparatively small area is cut over each year, the cost of logging may be very greatly reduced. Such a method is admirably adapted to certain forest regions in the United States, as, for example, to the Adirondack Mountains of New York, where the forest is composed about equally of coniferous and broadleaf trees. The conifers are the more valuable, and among them the principal lumber tree is the spruce.

|

| Fig. 18.—Natural forest resembling Localized Selection. Southern Oregon. |

The Bureau of Forestry has found by many careful measurements that if all spruce trees 12 inches and over in diameter are cut from certain portions of the Adirondack forest, the younger spruce will grow up and replace the original stand of timber in about twenty years. But this will not happen unless the rules for cutting are faithfully observed, nor will it happen more than once unless enough old trees are left standing for seed. Such a forest may then be divided into twenty parts, and the merchantable timber about 12 inches in diameter may safely be cut from one division every year. By the time the last of the twenty divisions has been cut over, the first will have upon it a stand of mature spruce equal in quantity to that of twenty years before. The yield of the whole forest in spruce for a single year may be cut each year from one-twentieth of the whole area. If all the divisions were cut over five times in the life of a mature tree, then one-fifth of the standing timber would be taken from each division at each cutting. Thus, if it took one hundred years for a tree to become ripe for the ax, the cutting (at intervals of twenty years) would retain five times during the life of the tree, at its twentieth, fortieth, sixtieth, eightieth, and one hundredth years.

|

| Fig. 19.—Group of spruce under beech. Germany. |

This is the system of Localized Selection. It is simple and easy to apply, and even if mistakes occur they are not apt to have dangerous consequences. It is very elastic and has many forms, and it is well adapted to many different kinds of forest. Logging is cheap, because the area cut over in any one year is small, and the reproduction is provided for by natural seeding in the openings of the forest.

THE GROUP SYSTEM.

|

| Fig. 20.—Mimic crest, showing distribution of young growth under the Group System. |

It often happens that all the trees of a small group in the forest are killed by fire or insects at about the same time. In the opening thus made the ground is quickly covered with young growth, which extends back under the old trees as far as the light will permit. The seedlings are usually tallest, strongest, and most numerous directly under the middle of the opening, and gradually decrease at the sides. If the wind should throw some trees at the edges of such an opening, the young growth would gradually extend, and if the same thing should continue to happen, in the end all the old trees would have disappeared and their places would have been taken by young growth. The Group System is an imitation of this process. Under the Group System openings are made here and there in the forest by cutting away ripe trees. As the reproduction proceeds, the old trees about the openings are gradually cut away, and the groups of young growth, spreading from the original openings like drops of oil on water, finally meet.

|

| Fig. 21.—Large group of young planted oak. Sir Dietrich Brandis and the English forest students of 1890. Germany. |

This is one of the simplest and most useful of all the systems, and when the openings are made small at first no other is so safe. It is especially adapted to small pieces of forest, such as woodlots, because it is simple, and because it assures the safety of the forest even with very little skill or care on the part of the owner.

THE STRIP SYSTEM.

In nearly every wooded region of the united states a tornado occasionally destroys the trees in a long and narrow belt through the forest. Fire often follows and clears the strip by burning up the fallen timber. Seeds then fall in the opening, carried from the trees on either side, the seeds germinate and grown, and the reproduction of the forest takes place.

|

| Fig. 22.—Spruce managed under the Strip System. Southern Russia. |

When the ax takes the place of the tornado and the timber is logged instead of being burned, the Strip System is applied. Reproduction follows from trees on either side, as before. The Strip System consists in cutting long narrow openings in the mature timber instead of the circular openings of the Group System, to which it is similar in many ways. It is simple and effective when natural reproduction is good, and well suited for extensive operations in places where careful work is impossible. The strips are usually not over 100 yards in width. Where the soil is dry, they are run east and west to protect the young growth against the sun, and are comparatively narrow. If there is serious danger of windfall, they lie at right angles to the direction of the wind.

These are the more important of the silvicultural systems. They have many modifications, and indeed each forest may require a special form if its own, which must be devised or adapted for it by the forester. But whatever the form, the object is always to use the forest and provide for its future at the same time.

|

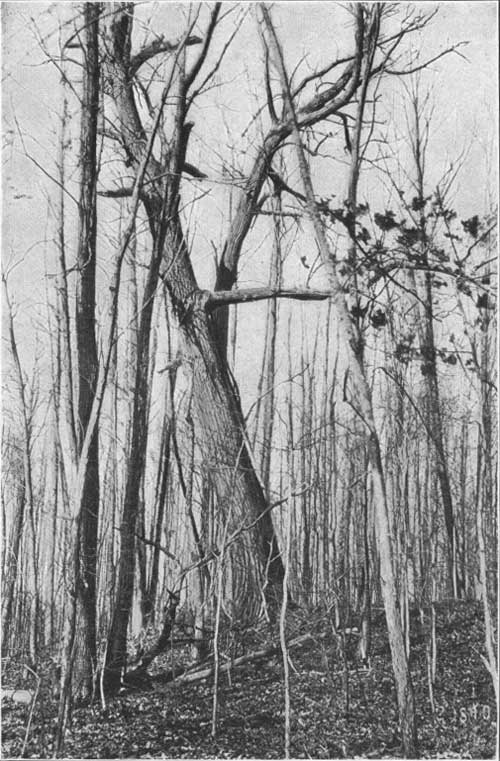

| Plate VIII. A MIXED FOREST IN NEED OF AN IMPROVEMENT CUTTING. The crooked old chestnut in particular should be removed. |

|

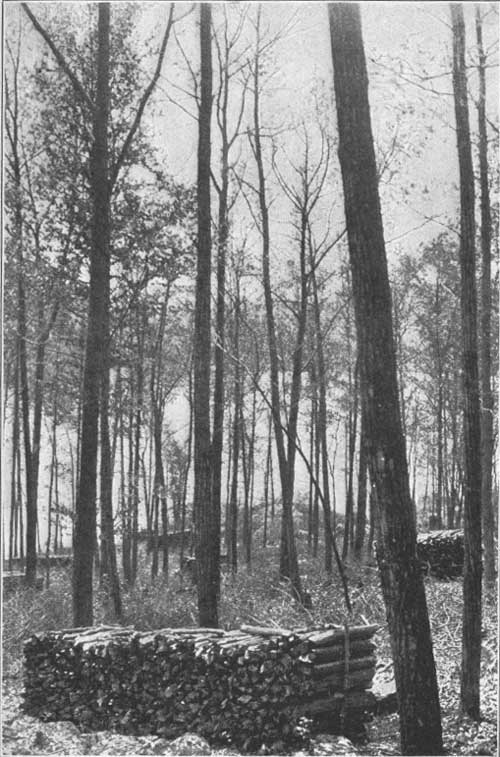

| Plate IX. A MIXED FOREST AFTER AN IMPROVEMENT CUTTING. |

IMPROVEMENT CUTTINGS.

Very many forests in the United States, and especially many woodlots, are in poor condition and unfit for the immediate application of any silvicultural system. They need to be put in order, and for the purpose Improvement Cuttings are usually required. In the end these cuttings should remove all trees which the forest is better without, but they should be made gradually, so as not to open the cover too much and expose the soil to the wind and the sun. In general, it is unwise to cut more than 25 per cent of the poles and older trees in a dense mature forest, or to cut oftener on the same ground than once in five years. Improvement Cuttings of course should never fall on trees which are to form the future crop, but they should remove spreading older trees over promising young growth; poor trees which are crowding more valuable ones; unsound trees whose places will be taken by others of greater value, or which are themselves becoming less valuable from year to year; and seed trees of undesirable species likely to reproduce themselves, if reproduction of more useful kind is well assured. The great majority of woodlots need such cutting, and when they do, whatever wood is taken from them should be cut in this way.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

primer/chap1-2.htm Last Updated: 06-Jul-2009 |