|

The Clearwater Story: A History of the Clearwater National Forest |

|

Chapter 16

Fire Control

The Clearwater Forest has a rather heavy annual precipitation. At Pierce the average is about 42 inches. It is even more at points of higher elevation. At Orofino, which has a much lower elevation, the annual precipitation averages about 26 inches.

If this moisture was evenly distributed by months, there would be little reason to fear forest fires. However, such is not the case. In almost every year there is a time during the months of June, July, August and September when the forest became dry enough to burn. There have been a few years when rainfall was so great or well distributed every month that fire protection would not have been needed. In my memory only 1916, 1943, 1948, 1956 and 1976 could be so classed.

On the opposite side there have been years when rainfall during the summer months was confined to a few thunder showers. I will list only the notoriously bad fire seasons. There have been other years with low rainfall but these will serve as an illustration. These with their summer month's rainfall at Orofino are as follows:

| Year | June | July | August | September | Total |

| 1910 | .18 | .05 | .02 | 1.06 | 1.31 |

| 1919 | .07 | .21 | .19 | .30 | .77 |

| 1929 | 2.61 | .00 | .05 | .53 | 3.19 |

| 1934 | 1.79 | .00 | .00 | 1.01 | 2.80 |

The Branch of Fire Research in Missoula analyzed the fire reports for North Idaho and Montana and found that the number of fires started on the Clearwater Forest per 1000 acres of area was the highest of any forest in Region One. Fifty or sixty fires from one lightning storm is not unusual. There are few man-caused fires on the Clearwater when compared to the number caused by lightning. This does not mean that there have not been some very costly and damaging man-caused fires.

Since there are so many lightning fires, it is easy to understand why forest fires have swept over large areas of the Clearwater Forest as far back as history is recorded. In their travel over the Lolo Trail, Lewis and Clark reported that Wendover Ridge, which they climbed from the Lochsa to the divide, was a "burned and windswept ridge". They also tell that when camped at Eldorado Meadows in June, the Indians entertained them by setting fire to some tall trees which burned throught the tops, presenting a display similar to fireworks. They also reported that the mountains on the north side of Eldorado Creek were burned, while the south side was green.

John B. Leiberg traveled over the Bitter Root Reserve in 1898 and studied the conditions. His study was thorough and his report should be considered the most authentic that can be found on conditions at that time. Here are some of his statements about fires: "In the North Fork and Lochsa basins badly-burned areas. . . . North Fork of Clearwater basin 76,800 acres, Lochsa basin 701,000 acres." This is a total of 777,800 acres. At another place he states, "The amount of destruction brought by fires of modern date is enormous. The largest continual block of forest in the Reserve comprises about 200,000 acres. The balance is all made up of numerous smaller stands separated from one another by long, wide lanes or large expanses of burned forests.

Dr. Shattuck, Dean of the Idaho School of Forestry, who examined the Forest in 1910 before the big fires of that year, had this to say: "We often rode for miles among the blackened and fallen trunks of what had formerly been magnificent stands of valuable timber, now only a jumble of decaying logs." Again he stated: "This ridge has practically no living timber remaining on it. . . . From this eminence, by the aid of a field glass, one can easily determine that the condition here obtaining is the same as that on practically all the ridges within a radius of 25 miles." Later he added: "Fire on this Reserve has produced far greater loss than all other agencies combined and is today the most dreaded and dangerous forest enemy with which we must contend."

After the Reserves were established, the first order of business was, as it is now, to suppress forest fires. Without experience no one had any idea of the enormous task before them. From 1899 to 1910, there were a few Rangers with little assistance scattered through the forests. They fought fires the best they could, and due to favorable weather conditions and a lot of hard work, they were moderately successful. However, at times they were forced to admit defeat. Ranger Stuart in his diary of 1904 reports going to a fire in the North Moose Creek country that was so large he could do nothing with it and was forced to abandon it.

1910

The year 1910 will long be cited as the year of the big fire. Actually there were many fires. Books have been written on this season's activities and large burned areas all over the Northern Region give mute testimony that this was indeed a bad fire year.

There was no advanced warning that 1910 was going to be anything other than an average fire year. The snowpack of the preceeding winter was heavy and late in melting. Rainfall during the early spring months was normal or a little above average. May had a rainfall of 3.89 inches at Orofino, compared with a normal of 2.31.

June was a different story. It was hot and dry. Only .18 inch of rain fell at Orofino. This was followed by a blistering hot July with .05 inch of rain which came during a dry lightning storm that started numerous fires.

|

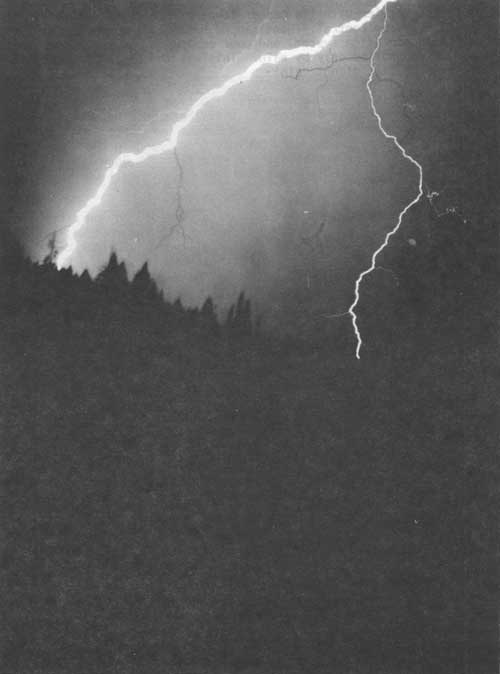

| The cause of virtually all early-day fires and most modern fires in the Clearwater country. |

The Forest Service with its meager force of men fought valiantly to bring the fires under control. Handicapped by lack of communication, an inadequate transportation system, and poor equipment, it was a situation that could be controlled only by rain. This was the big hope. Hang on until it rains; but it didn't rain!

Gradually the situation became worse. During late July and early August fires escaped control and spread so that there were numerous large fires scattered over the forests. Fires on the Lochsa were spreading from their starting points in Fire Creek, Warm Springs Creek, and in the Upper Crooked Creek. In the North Fork drainage there were fires on Burn Creek, Cayuse Creek, near the mouth of Kelly Creek, Hemlock Creek, Skull Creek and perhaps others.

My remembrance of 1910 is that of a nine-year-old boy on a homestead between Weippe and Pierce. The smoke from fires to the west was so thick that it reduced the summer sun to a yellow ball you could look directly into without hurting your eyes. Semi-darkness came at about 4 P.M.; it was so dark that the chickens went to roost. When it finally rained, our eyes were so accustomed to the darkness that the bright sun caused our eyes to water.

By mid-August everyone became a little more hopeful. While there were a lot of big fires, it was believed rains could not be far away.

On August 21 the wind began to blow. Not just an ordinary wind, but one that kicked up the dust and swayed the trees violently. In a very short time, the fires became raging infernos. It then became a matter of saving life. Efforts to fight the fires were useless. It was a question of getting out of the way or finding a place where a safe stand could be made until the fire passed. Fortunately, so far as I can learn, no life was lost on the Clearwater.

Two Forest Service men at Hansen's first cabin on Kelly Creek (near the mouth of Deer Creek) took to the creek for safety. They tied their horses to willows near them. One horse broke loose and raced the fire to Superior, Montana and made it. The first Hansen cabin on Kelly Creek burned while the brothers were at their mine. At the mine they managed to save their cabin after a hot fight. This area is high and rocky. Looking at it today, the fuel is so light that you may well wonder how a fire could burn at all. Billy Rhodes' old cabin burned.

A crew of men, led by Ranger Friday and including John Blumhagen and Fred Foss, was cut off by the Skull Creek Fire and fled northward. They came to what to them was an unknown river (St. Joe). They managed to come through alive and then went downstream coming out at Avery. It took them several days to make the trip. They subsisted chiefly on grouse that had their feathers so badly burned that they couldn't fly.

Lottie Walde says that she, her father Bill Parry, her mother, and an assistant packer along with their packstring were surrounded by a fire somewhere in the Hoodoo Lake country. Lottie and her mother took to the lake. The men covered the horses with blankets and threw water on them with a bucket. They all came through unharmed.

The wind raged for three days and nights. One of the peculiarities of these fires was that they burned just as fast at night as they did during the day. At the end of the third day there was a little rain, and snow fell on the higher mountains. The rain was light, but the cooling temperature ended the fire season.

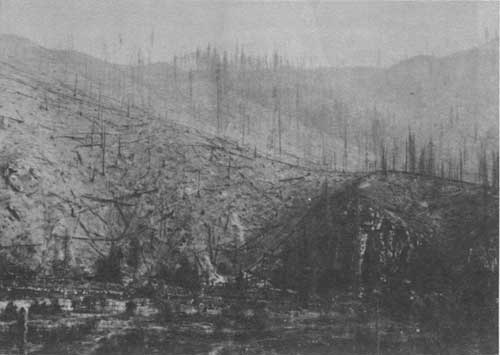

The Clearwater Forest had a tremendous area burned in the 1910 fires. The fire that started on Fire Creek burned up the south side of the Lochsa covering Old Man Creek and Boulder Creek to Fish Lake. Further up the Lochsa, the Warm Springs Creek drainage burned and the fire on Crooked Creek burned the head of that creek and crossed the divide into the Lolo Forest in Montana. On the North Fork a large part of the Weitas burned, Collins Creek burned, and the fire that started at the mouth of Kelly Creek burned up that creek and over the divide into Montana. Of course, some of this area, had been partially burned in earlier fires.

|

| The 1910 fires ravaged thousands of acres. Looking downstream into Kelly Creek. |

1914

The fire season of 1914 was very dry during the month of July and August when a total of .02 inch of rain fell at Orofino. There was not a large burned area on the Forest that year, but there were several troublesome fires. A large fire on Washington Creek started on lands protected by the Clearwater Timber Protective Association and entered the Forest north of Elk Mountain.

In 1959 a fire on Washington Creek occurred under similar conditions. Comparison of the action, methods of fighting, equipment use, transportation, etc. is interesting.

The 1914 fire started on the north side of Scofield Creek. It was called the "Scofield Fire". The exact location is probably unimportant, but it was near the mouth of Middleton Creek. The date it started is unknown, but it was about August 10.

This fire escaped control of the initial crews of the Association and spread eastward down the north side of Scofield Creek. Extra crews were employed but the fire spread faster than firelines could be built. The Association was successful in cutting the fires off from spreading up Washington Creek and went down it on both sides. John Durant was Ranger at the Oxford Ranger Station and through the lookout at Elk Mountain and his own observations kept watch on the progress of the fire.

About August 15 it became apparent that this fire would enter the Forest if control measures were not initiated. Action was started by sending a man who was an experienced firefighter to look over the situation. He rode to Elk Mountain and after looking at the extent of the fire estimated that 200 men would be needed.

At that time it was almost unheard of to have 200 men on a fire. Durant pointed out that it would take more than men to fight a fire. To this he agreed and set out to organize a supply service that would back up 200 men.

The nearest large supply of men was at Spokane, Washington. Men were recruited the day ordered. The next day they came by passenger train to Greer. There they were loaded into passenger cars and taken to Pierce. The next day they hiked to the fire camp. It took four days to get these men on the fire and many of them were worn out when they arrived.

Tools and supplies moved even slower. The local stores were unable to supply tools and food in sufficient quantities. Material was ordered from Lewiston. Because outfits were not assembled, every single piece of equipment and every pound of food had to be ordered by name and amount.

Tools and supplies were ordered from Lewiston in the evening. The next day they were assembled and loaded. The third day they went by freight to Greer and were loaded on wagons that night. Trucks were not yet in use. On the fourth day they reached Pierce. The fifth, they reached the Oxford Ranger Station and were cargoed that night. The sixth day they reached the fire camp.

Meat was a very difficult problem because it would spoil on the road. At one time the Forest Service considered buying cattle and driving them to Oxford to be butchered. However, this did not become necessary; the meat butchered at Weippe reached the fire camps in an edible condition.

With such a complicated supply line it is small wonder that fire fighting was not very effective. Of course, considerable fireline was constructed and no doubt much timber was saved. But the fire was not controlled until the fall rains came.

On the first Monday in September (first day of high school for me) it rained. From that day on through September rain was almost continuous. Summer dust turned to mud; the roads became impassable to cars. Even freight wagons operated at about half of summer capacity. To get the men, equipment and tools off the fire was a slow and laborious process. Men hiked to Weippe. On my return home from high school, I met many of these crews. They all wanted to know how far it was to "We-hike".

A base was set up at Weippe under the direction of a man named Conrad. He assembled tools, men, stock, etc. and sent them to their final destination. It was almost the end of September before he was able to close camp.

Contrast this action with that taken in 1959.

A lightning storm set a number of fires in the Washington Creek area on August 1 at about 7 A.M. The Clearwater Timber Protective Association manned these fires, but four of them escaped initial attack. The Clearwater Forest anticipated that the Association would get control, so took no action until the afternoon of August 2.

The Clearwater Forest had just suppressed a large number of fires and was also giving the Nezperce Forest assistance. To throw an effective force against this fire it was necessary to get a large part of the manpower from the Kaniksu Forest.

The Clearwater was able to attack with only a few men and two dozers on August 3. However, they did scout the fire and established a fire camp at the old Oxford Ranger Station.

At daylight August 4, the Forest Service with Ranger Radtke as Fire Boss and assisted by Gus Verdal attacked with 360 men, 25 power saws, 4 bulldozers, a helicopter and enough trucks to transport men from camp to the fireline. That day the Forest Service built and held about 4 miles of fire line. The next day the Forest Service did mop-up work on the four miles of fireline it had built and took over about three miles of line built by the Association. This enabled the Association to control the remainder of the fire.

Demobilization started on August 6 and by August 9, twenty men were all that were left on the Forest Service sector.

1919

In 1919 I became a smokechaser for the Clearwater Timber Protective Association. I had two brothers smokechasing on the Clearwater National Forest. One of them was at Scurvy Mountain and the other at Hemlock Butte. During the early part of the season I was on a trail maintenance crew and traveled over many of the trails and visited many of the Association lookouts. During the latter part of July and all of August, I was stationed at Bertha Hill. I had a ringside seat from which to watch what was going to happen.

Unlike 1910, the year of 1919 had early makings of a bad fire year. Winter precipitation came largely as rain. The snow came mostly in March. This snow did not pack and quickly melted. By early May the snow was gone, except on the high ridges and mountains.

About May 20, the rains ceased and the long drought started. There is an old saying on the Clearwater that 10 days of clear summer weather and the forest will burn, and 20 clear summer days produces critical fire conditions. True to this saying, the forests were ready to burn in June. A blast by a trail construction crew set a fire near Cave Creek which burned several acres before it was controlled.

During July the forest became drier and drier. The brush turned brown and the trails were inches deep in dust. Although there were no fires on the Clearwater by July 19, according to lookout John Austin's diary, visibility was becoming very poor due to smoke from other forests.

On July 21, the first lightning storms came with a rash of fires. All hands turned to fighting fire. Most fires were held to small acreages, but fires on Larson Creek, Lolo Creek, Fish Creek and Split Creek got under way. However, by a strenuous effort that exhausted men, mules and supplies, all of these fires except those on Fish and Split Creek were brought under control.

On July 31, a number of lightning storms (Austin says four) crossed the Clearwater leaving a string of fires behind. Again all men went to work on these new fires. Progress was being made when on August 3 another lightning storm raked the Forest. Larson Creek, Deadhorse, Elk Mountain, Lolo and Weitas were liberally sprinkled with fire. Forest crews and firemen were exhausted. Other men were scarce and those brought in from Spokane were mostly IWW and wouldn't work. Butte miners were not very effective. Bringing in enough pack stock, equipment and supplies was a problem due to lack of roads and trails. Supervisory personnel in any numbers did not exist.

|

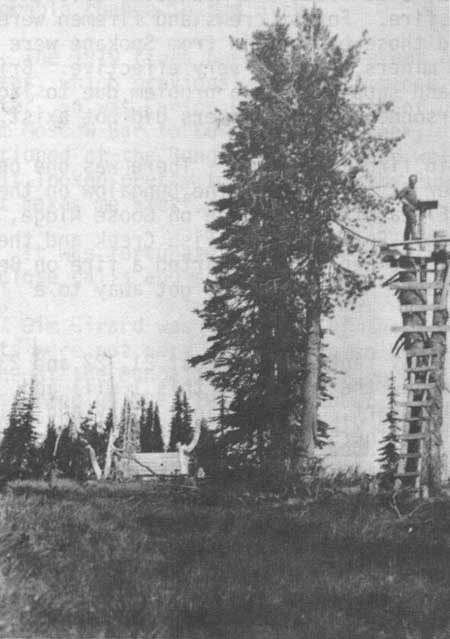

| The first lookout on Cook Mountain. Built by Paul Wohlen in 1917. |

|

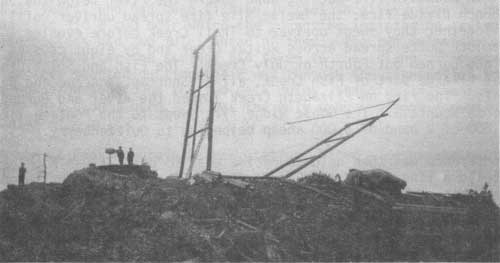

| Raising the first lookout on Bear Mountain in 1924. |

As the days went by, several main fires developed. There was one on the east side of Elk Mountain, another 12 miles below the Bungalow on the southeast side of the river, one on Elizabeth Creek, one on Goose Ridge, one on the Hunch Divide now called Cabin Point, one on Fish Creek and the Split Creek Fire. At about this time a sheep herder started a fire on Belle Creek, a branch of Lolo, to burn out some hornets and it got away to a flying start.

Then came August 19, 1919. This day ranks with August 21, 22 and 23 of 1910. I will describe what I saw from Bertha Hill. To this I will add statements from A.N. Cochrell, J.C. Urquhart, John Austin's diary and things I learned by talking to my brothers and others who took part in the action.

August 19 dawned clear and hot, but I immediately noticed that there had been a change in smoke conditions. It had been so smoky that climbing the tower was useless since visibility had been less than one quarter mile. This morning the smoke was almost gone and what was left was fast disappearing. Soon a wind began to stir, but I do not believe it reached the strength of the winds of 1910. The humidity must have been very low, but of course no one measured it. The air became so clear that I could see every major fire in the country as far south as the Lochsa River.

By 10 A.M. every major fire was on the move and had started to roll up a high column of smoke resembling a thunderhead. I timed the Twelve-Mile fire as it climbed Pot Mountain. It required just a few minutes over one hour to move an airline distance of about five miles. Pulled by air currents from the Elk Mountain fire backing down toward the river below the Bungalow, and the Hunch Divide fire, the Twelve-Mile fire spread upriver until they joined. Together they swept upriver to Trail Creek before evening. The fire around Hemlock Butte spread across Weitas Creek and by night crossed Cook Mountain and burned out Fourth of July Creek. The Fish and Split Creek fires burned out a large part of Fish Creek, all of Sherman, Noseeum and Balk Mountain Creeks. The fire on Elizabeth Creek jumped the river and burned to the top of Moose Mountain. The Goose Ridge fire swept to the Montana line, burning up 1,500 of a band of 3,000 sheep belonging to Quizzenberry.

A conference was then held to decide what to do. It was hopeless to try and build a line around such large fires with such a meager force. The only thing that could be done was to save any drainages that were threatened but not burned. A fireline was built across the lower end of Orogrande and some other lines in the west sides of the Lolo and Split Creek fires, but that was all. The wind stopped and the smoke, which had lifted on the 19th, settled so thick that visibility again became almost zero and remained that way until the rains of August 31 and September 1. Strangely enough, the fires spread very little after August 19. In some places the fires ran into the 1910 burned area which slowed the burning, and there was apparently a favorable change in humidity.

The 1919 fires burned large areas of merchantable-sized timber. The Wietas, which previously had an immense stand of timber, was a blackened waste. So was Larson Creek, Fourth of July Creek and the North Fork Canyon from Moscow Bar to Cold Springs Creek. Jim Clark, an old-time smokechaser stationed at the Bungalow, expressed well the feeling of everyone when asked if it looked pretty tough around the Bungalow. He replied, "Yes sir, it just makes me sick".

It was fortunate that there were not fatalities. There were a number of close calls and some harrowing experiences.

Jim Girard was in charge of the Twelve-Mile fire. His suppression efforts were not very successful, so he decided to walk to the nearest telephone at the Bungalow and see if he could rustle up more men and equipment. He started up the river. At about Cave Creek he became aware that the fire he had left was spreading rapidly and was coming up the river behind him. He increased his pace, but it soon became apparent that he was losing ground. He reached a point about five miles below the Bungalow where the trail ran back into a draw and out. The distance by trail was one quarter mile; the distance along the river was less than half that. Jim decided to follow the river bank and cut across this loop. Not that he would save any time, but he preferred to stay close to the river. This was a fortunate decision for here the fire overtook him with all its fury. He knew he was in a tough spot so he wrote his will and cached it under some rocks at the water's edge. By wading back and forth across the river and taking frequent dips below the surface, he came through alive.

Two packers, Charles Kelly and Lawrence Howard, were coming down the river toward the Bungalow. They met the fire head-on with no knowledge that they were anywhere near it. They immediately took to the small island below the mouth of the Weitas with their strings. An old Indian and his grandson of about 12 years, who had been fishing in that locality, took to the same island as also did a cub bear which the youngster insisted on trying to capture. The packers had two mules ahead of them. The two mules proceeded on towards Bungalow after the strings had taken to the island. The next morning the packers started cutting their way through the fire-felled trees toward the Bungalow and found the two pack mules, standing in the trail in a small spot that didn't burn. It was the only unburned spot for miles in any direction.

The men at Cook Mountain Ranger Station, after a desperate battle, saved the cabin.

At Elizabeth Creek the fire broke loose and jumped the river. Urquhart was on the north side. He got the crew on that side out of the way. To reach the crew on the west side he went down the river through the fire. He almost suffocated. When he came out of the fire he passed out for a short time. When he came to, he found himself lying in the water at the mouth of Elizabeth Creek.

At Hemlock Butte the small group of men, including one of my brothers, was warned that they were to get out of the way the best they could. They decided to leave the point and take refuge in a small meadow with a creek running through it. This was in the head of Hemlock (then called Beaver) Creek. The fire surrounded them and they fought for their lives. They came through, but one member of the party (Richards) went insane. For a time he recovered from this condition, but several years later was confined to a mental hospital. They returned to the lookout on Hemlock Butte and were much surprised that it had not burned.

A.H. (Pete) Ott, a foreman, and Tom Hamilton, a cook, were located at the Bungalow. Pete had been foreman on the trail upriver, but with his crew on the fire he was serving as a dispatcher for men and supplies at Bungalow.

About 1 P.M. he and the cook were alone. Pete thought the fire down the river, which he could see dimly through the smoke, was moving toward them and called Tom to the door and asked him what he thought of the looks of things. Tom said, "Heck! I'm cooking on a hotter fire than that", and went back to his cooking.

About one hour later a raging inferno turned the bend down the river! Ott and Hamilton hastily grabbed a few belongings and fled up the Orogrande. Tom, being older and the slowest traveler, was ahead and set the pace. Pete kept a close watch over his shoulder until he saw the fire cross the trail behind them near the two mile board. They were safe and stopped to catch their breath. Pete asked, "What time was it when we left?" Tom relied, "It was just 2 o'clock. I had just put the cinnamon rolls in the oven and looked at the clock." Pete pulled out his watch and it showed three minutes past two. If their timing was correct it was pretty fair time for a seventy year old.

On the last day of August it rained. It started at about 9 P.M. All of us at Bertha Hill had just gone to bed when a few drops began to fall. Everybody got up, stripped off their clothes and went outside, so glad we were to see and feel it rain. It rained on into the next day and put an end to the critical fire weather. However, it continued to be dry through September and set the worst drought record in Clearwater history. A total of .77 inch of rain in four months! A good shower will often produce that much water.

|

| Baking bisquits in reflector ovens in a 1919 fire camp. |

|

| Bungalow Ranger Station in 1920 following the devastation of the 1919 fire. Looking across the North Fork and up Orogrande Creek. |

FIRES AFTER 1919

The really old burns plus those of 1910 and 1919 had left the Clearwater Forest with a tremendous burned area. There were hundreds of thousands of acres of burn. These burns, particularly those of 1919, were a sea of snags. Within a few years these snags began to fall. The combination of snags, brush, reproduction and down logs produced a mass of unbroken fuel extending for miles.

To defend such an area from a reburn looked almost hopeless. There was much discussion which even went down to the firemen about what should be done. Some wanted to reburn patches or strips and some wanted to build fire lanes. Others, noting the fine reproduction that came in after a fire, wanted to defend it all in the hope that, although some of it would burn, a large area would come through without a reburn.

A fire survey was conducted in 1921 and 1922 to examine conditions and recommend the action to be taken. This party was headed by C.E. Sutton. It was the first effort to make a complete fire plan for the Clearwater Forest. A number of recommendations, such as trail construction were ultimately accomplished. But so far as areas recommended for controlled burning (Sutton used that term) and firebreak construction were concerned, none of this work was ever done. Only a few areas were recommended for controlled burning. The many firebreaks suggested were later considered of little value and were not built. As a matter of history, the areas recommended for control burns because they possessed such high fire hazards have not reburned to date. They have now lost much of their fuels through decay.

With all the high fuels (and it became progressively worse up until about 1939) it was inevitable that there would be some large reburns. Unfortunately, in some instances, these fires spread to green timber and added to the already extensive burns.

| 1922 | A 3,000 acre fire at Scurvy Saddle, all in old burn. |

| 1924 | Bernard Creek watershed reburned. |

| 1926 | Skull Creek reburned plus some green timber. Larson Creek also reburned and added Lightning Creek to the burned area. |

| 1928 | A fire starting near Weitas Butte reburned a large area in the Weitas. This was a very destructive fire so far as reproduction was concerned. |

| 1929 | A fire started on Bald Mountain covered both sides of the Lochsa Canyon to above Colgate Warm Springs. This fire covered parts of Weir, Fish Lake and Lost Creeks not previously burned. |

| 1931 | A large part of Hemlock Creek reburned, plus a part of Sylvan Creek. |

| 1932 | More of the old burn in Fish Creek reburned with considerable green timber. |

The Forest Service always had some sort of fire control plans, but at first the plans reflected what the Forest planned to do with the money alloted to it. In 1932, under the leadership of Lloyd Hornby, the Region started to make plans that were based on needs. They were called Adequate Fire Control Plans. This was a grassroots effort. The fuels were mapped on the ground showing the rate of spread and the resistance to control. The area that could be seen from every peak that could be considered as a possible lookout was mapped. Travel time was also placed on maps showing the area that could be covered by each fire goer. This was then all worked into a plan that combined detection and fire suppression action. It was recognized that some fires would escape the first attack so a system of roads and airplane landing fields were planned that would make it possible to put large crews on these fires.

This was a thorough job and it showed need for men, equipment, roads, landing fields and other improvements far greater than the Forest Service had ever had before. The Forest Service was not able to put these plans completely into effect, but they moved a long way in that direction. Under the various emergency programs many miles of fire control roads were built, landing fields developed in the back country and lookout houses erected on many peaks.

|

| Burned area near Camp Martin, 1925. |

1933

In the early thirties, I believe it was in 1933, the 10 A.M. control policy was adopted. It was often referred to as the Chief's policy, but actually it was the kind of policy the field men had long wanted. This policy was that for every fire, regardless of location or the values involved, plans would be made to bring it under control by 10 A.M. of the next day. Ten A.M. was considered the start of the day's burning period. Before this policy was adopted, those responsible for fire control worked under a "damned if you do and damned if you don't handicap". If a fire was quickly suppressed the charge was often made that it wasn't doing any damage or that money could have been saved by using less men, but if the fire escaped control, then the criticism was that action was not aggressive enough. Through the years the 10 A.M. policy proved to be a sound policy.

|

| Hemlock snags along the Lolo Highway near Rocky Ridge, 1938. |

1934

The 1934 fire season was very dry. The Clearwater National Forest, as it existed in 1934, did not have any large fires, but the Selway Forest had plenty of trouble. A large part of the area that burned that year on the Selway is now a part of the Clearwater Forest. This burn was almost entirely due to the Pete King and McLendon Butte fires. The history of the fire season of 1934 is the history of these two fires.

On August 11, 1934 eighteen fires started on the Selway Forest from a lightning storm. Among these were the Pete King and McLendon Butte fires. There had been 45 days without rain. Then after the fires started, another 32 rainless days followed. This was truly critical fire weather.

The Pete King and McLendon Butte fires both started in single burns of 1919 and 1917 respectively. The points of origin were in areas of cedar snags, down timber and brush. This fuel type covered a large area surrounding the points of origin and was considered one of the worst fire hazards in Region One.

Initial action on both fires was fast, but failed. Both fires started at about 4 A.M. and by nightfall the McLendon Butte Fire covered an area of about 1,500 acres and the Pete King about 5,000 acres. There were spot fires as much as four miles ahead of the main part of the fire. The McLendon Butte fire had spot fires across the Lochsa and across Fish Creek about a mile above the Lochsa Station. The stage was set for a major burn.

During the days that followed almost the entire resources of Region One were thrown against these fires. Involved were about 5,500 men in 74 fire camps of from 50 to 200 men. Five fire camps burned. Four hundred seventy-five head of packstock were required to supply the camps, 100 trucks and 15 cars were used. In addition, airplanes, private trucks and busses were used to transport men, equipment and supplies from Spokane and Missoula to the base camps.

During the 32 days that these fires burned, the Pete King Fire moved down Pete King Creek and jumped the Lochsa River. It then sent a mighty arm up the Selway to Halfway Creek. It also burned up the south side of the Lochsa, jumped back to the north side near Old Man Creek, then on up the river on both sides running into the McLendon Butte Fire. The McLendon Butte Fire went up the Lochsa to Bald Mountain Creek where it ran into the 1929 burn where fuels were so light it made little progress. The total area burned by both fires was 252,250 acres, about 100,000 acres of which is now on the Nezperce Forest. There has not been another fire anywhere near this size in Region One since 1934.

In almost every year of bad forest fires, there is a short period, usually one day, which stands out as far more destructive than all the rest. In 1910 it was August 20-21 when the forests roared and millions of acres burned. In 1919, August 19 was the day when the Bungalow burned and a huge area was covered with fire. These days are often termed "disaster days" by the public, but to those who fight the fires they are called "blow-up days". Call them what you wish, but these are the days when a hot dry wind hits the fire. This wind, plus the wind generated by the heat of the fire, causes the fire to get so hot that it burns trees like a prairie fire burns grass. A fire on such a day cannot be stopped. It can go anywhere. Many stories are told of the speed, power and strange things done by such infernos. A cloud of smoke raises over such a fire that looks very much like a thunderhead or the plume from an atomic explosion.

Such a day was August 17, 1934. That day the McLendon Butte and Pete King Fires covered 53,300 acres between 10 A.M. and 8 P.M.; an area of about 4,400 acres per hour. That day separate forces of men fought to save the Pete King and Lochsa Ranger Stations.

It took a real fight to save the Pete King Ranger Station. But the fire came downhill at it, the river was close at their back and there were more pumps and other equipment to assist in the fight than there were in the battle to save the Lochsa Ranger Station. Without belittling in the least the efforts or detracting from the honors due to those who fought to save the Pete King Ranger Station, I will attempt to describe the battle to save the Lochsa Station which was a much harder fight.

I believe it will be easier for me to tell the story and for the reader to understand what happened if I start on August 11 when the fire started. The fire control organization, as far as the first action on this fire is concerned, consisted of Ranger Leroy (Roy) Lewis, who happened to be at Fish Lake when the fire started, Assistant Ranger Jack Godwin and Headquarters guard Warren Bohn at the Lochsa Ranger Station. McHone was lookout on Fish Butte. Mrs. Lewis, not a part of the fire organization and the only woman involved, was at the Lochsa Station.

The fire started at 4 A.M. August 11 about one half mile northeast of McLendon Butte in a snag patch left by a fire in 1917. It was a lightning fire and was quickly detected. A CCC crew went to it, but could not bring it under control. Another CCC crew soon arrived but still the fire continued to spread. About 10 A.M. a snag burned off and fell and then slid down the mountain toward Fish Creek. This scattered fire along a narrow strip for about a quarter of a mile. Shortly thereafter this whole strip blazed up into a raging inferno. The fire then swept back up the mountain to the southwest, widening and gaining such force that it threw a spot fire across the Lochsa River over three miles away. Another landed across Fish Creek above the Lochsa Ranger Station four miles away. There were many other spot fires closer to the main fire. In a matter of an hour this fire had scattered over 1500 acres and set the stage for a major burn.

Early in the morning of the day the fire started an airplane picked Ranger Lewis up at Fish Lake. He scouted the fires from the air and landed at Kooskia. From there he traveled by car to the main or base camp fighting the McLendon Butte Fire which was established at the head of Bimerick Creek. Here Lewis assisted in directing action on the fire under Clayton Crocker who was Fire Boss.

Before the first day was over it became apparent that the Lochsa Ranger Station was in danger. Ranger Lewis telephoned his wife, Mabel, and told her to leave but she was reluctant to go. She said that she could stay if the men did. But her husband insisted and she left the next morning riding her saddle mare up the Sherman Creek Trail. Her brother, Harmon Snyder, picked her up at Noseeum Meadows and took her to her father's ranch west of Weippe. She did not return until it rained.

The Fish Butte Lookout had spot fires all around it so the lookout, McHone, fled to the Lochsa Ranger Station and helped in the activities there. The lookout building burned.

On the next day a CCC crew of about 200 men and a road crew of about 30 men arrived at the Lochsa Ranger Station and set up a fire camp.

During the days of August 13-16, good progress was made in fighting the fire. The spot fire above the Station was controlled and considerable line built above Fish Creek on Fish Butte. The line was being pushed up Fish Creek, but there the fuels were very heavy and construction slow. However, the situation did look much better.

Then came August 17! The crews went to work on the fire as usual. About 10 A.M. the station received a message from the Weather Bureau that there was a high wind coming. Shortly thereafter the fire began to pick up and it was evident that the fire was going to make a run before the end of the day.

The bosses on the fire soon concluded that they would not be able to fight fire that day so they gave orders to withdraw the crews to the Lochsa Ranger Station. There was still plenty of time and the withdrawal started in an orderly manner. However, with the fire rolling up a cloud of smoke behind them, the retreat became a panic. Many of the men threw away their tools in their mad rush down the mountain and up the trail to the Lochsa Station. A packstring taking supplies to the Station was overtaken by running and shouting men and it too was panicked. The mules broke loose and scattered packs along the trail. At about 12:30 P.M. this mass of people reached the Lochsa Station. Here it paused and the bosses restored order and the packer collected his stock.

The panicked crew was followed by those who had kept their senses. The teamster who handled the large horses (weight about 1700 lbs. each) came with his team and then on the end came Ranger Lewis. When the fire started to blow up, he had headed for the Ranger Station to join in the fight to save it. A roll call showed all present except Bill McDougal. Bill was a trapper in the winter, but worked for the Forest Service in the summer. He was an expert woodsman. He had been scouting the fire when it blew up. He didn't show up until the next morning. When he came to the Station it was evident that he had been in the water, either in Fish Creek or the River. He wouldn't say which, but he did say it was mighty hot.

Just as soon as the fire began to pick up at about 10:30A.M., Jack Godwin started the few men at the station to work preparing for the fight to follow. They built a dam in Zion Creek, forming a pond about 20 feet long, ten feet wide and five feet deep. They placed the only pump they had at this pond and strung hoses to the buildings. They did not have enough hose to reach all the buildings so the bunkhouse had no water. They also used the garden hoses which operated from the Station's water system which was a gravity flow from Zion Creek.

They distributed water buckets and water bags at strategic places and equipped them with hand-operated pumps as far as the number would go. There was not enough equipment to put all the men to work.

The teamster took oat sacks and sewed them together and made blankets for his team. By frequently wetting these blankets he saved the horses. The packer used the saddle blankets to cover the animals in his string the same way. They carried the oats and hay into the area to be protected. The hay shed and corrals were left without defense since any attempt to save them would be useless. They wet the buildings and the surrounding area down with the pump and garden hose.

Ranger Lewis and the foremen talked to the CCC crew. They told them not to run. Their chances of coming out alive were good if they stayed at the station but if they ran, it was sure death. Such talks no doubt help some, but a forest fire roaring down upon them with all its noise, fire, heat and smoke is a fearful sight and they sometimes lose their power to reason. They panic and run even though they know they should not.

By 1:30 P.M. the defenders were all organized and ready, Ranger Lewis was in charge and Jack Godwin would handle the crews with the pump. There was a crew for each building, each divided into two parts; one part to fight while the other rested and got its breath. Warren Bohn and four CCC men were to defend the radio poles, etc. At this time they could hear the fire's low pitched grumble, a great deal like a distant waterfall.

At about 2 P.M., the fire came over the hill west of the station. The hour of truth had arrived! Here the puny hands of a small crew of men would be pitted against the forces of hell! They set a backfire. Immediately in front of a big fire there is a suction that produces a wind toward the fire. Setting a backfire at this time holds the main fire back a little and they needed every aid they could get. The fire approached with all its noise, heat and smoke. Daylight turned to twilight as the smoke blotted out the sun. The crews stood their ground!

At first the fire did not come directly at them. It angled up the hill from the river and then up Zion Creek. It moved closer and the heat increased. The side of the cookhouse toward the fire began to steam and had to be wet down continuously. Then the upriver side of Zion Creek went whoosh as it burst into flame! The wind and the fire then came directly at them and across the buildings! The fight was on!

The battle lasted for about three hours! During this time the fire pump ran continuously and the men carried water! Thousands of sparks rained down, some as large as a dinner plate. One of the large embers landed on the main line of the fire hose and went undetected for a few seconds. The burning ember so damaged the hose that the pressure from within caused it to burst. Had it not been for a special effort of the men with the handpumps and water buckets the buildings would have burned! Just as the men were wearing out they got the hose repaired and the pump going again. They then wrapped the most exposed parts of the hose in wool blankets and had a man wet it down with buckets full of water.

Time after time a building would catch fire, but each fire was quickly hit with a stream of water. The hayshed burned and its burning shakes added to the embers that fell on them. The bunkhouse that could not be reached with the hose burned.

Ranger Lewis was in charge. He walked about through the protected area giving encouragement and keeping a sharp eye out for anything that might go wrong. He found a small group of CCC boys near Zion Creek outside the protected area. He hustled them out and this area soon burned over.

Jack Godwin and his pump crews stood the worst part of the fight. In such a crew every man fights two battles at the same time; one to save the buildings and the other to stay alive. Just how does a man survive in such an inferno? It isn't easy! Above all he must keep his clothes soaked with water from a hose or by rolling in the creek. This keeps the sparks from setting his clothes afire and helps cool the body. The smoke stings his eyes and the tears stream down his face. He gulps water not only to supply his body needs but also because his mouth and throat dry out from breathing the hot air. He fights fire only a few minutes, then drops to the ground to breathe cooler and fresher air near the ground, while the other crew keeps up the fight. He is a soggy, dirty, crying, coughing and spitting mess, but when the other crew has taken all it can, he is on his feet again and fighting the fire.

By 6 P.M. the fire passed! Warren Bohn said that he was first aware that the fight was won when noise dropped in volume. Then the pump stopped and all was deathly quiet except for the voices of the men; and they weren't talking much. The cooks had supper ready. The men were elated, but too tired to celebrate. They bathed in the pool and went to bed.

The next day the crew rested. The doctor was busy taking care of sore eyes and throats but there were no injuries. Smoke was still raising from some smouldering stumps and logs but the air was cool. Under the blanket of smoke that hung in the valley the temperature rose only to 70 degrees. The crew ate the noon meal with gasoline lights. Not a bird sang or a leaf rustled. The only signs of life were the swarms of smoke flies, that came from the Lord only knows where, and the ravens that flew over the burn. They were searching for and feasting on the animals the fire killed but had not completely burned. But there stood the Lochsa Ranger Station, an oasis in a blackened waste!

|

| Warren Bohn standing on the hillside by the Lochs Station after the successful battle to save it from the flames. |

|

| Looking across the river from the Lochsa Station following the fire. Smoke still shows. |

|

| Clarence Longteig, a cook, standing near the Lochsa Station after the fire. |

1938

In 1938 supplies were parachuted to a fire. Various devices had been tried with little success before going to parachutes. Free fall packaging, manties with ropes to the corners and other ideas were tried. The packages were either too small or hit the earth so hard that the tools were severely damaged. What was needed was a means that would permit dropping the bundles contained in the standard 25 man outfit. The parachute was adopted for this use.

Bob Johnson invented the static line that made this possible. He never patented this device. I once asked him why and he said the idea was so simple he never thought of patenting it. He added that had he done so he may have made more money out of it than he did out of the airplane business.

1940

The fire season of 1940 deserves special mention, but not because of the area burned, close calls or severity of burning conditions. It is a historical year because of the high occurrence of fires and the large force of trained manpower the Forest Service had to meet the fire emergency.

The figures below relate to the Clearwater Forest as it was in 1940. The areas that were subsequently added to the Clearwater also had high occurrences that year and had the manpower to control the fires with little damage. Actually what happened on the Clearwater Forest was duplicated on almost every forest in Western Montana and North Idaho. Region One had by far the highest fire occurrence in 1940 than it has ever had.

The number of trained men available to the Clearwater Forest to suppress fire reached its all time peak in 1940. At that time the Forest Service had a number of CCC camps of 200 men each. The Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine (BRC) also had several camps. In addition there were other crews available through emergency appropriations for road construction, blister rust control and other work. The total manpower was about a thousand men. All of these crews were well equipped and had trained, experienced foremen.

The fire season of 1940 started early. There were seven fires in May and 64 in June. The months of June and early July were very hot. On July 12 a dry lightning storm crossed the Forest leaving a liberal sprinkling of fires. There were 185 fires in July and most of them came from this storm. Here is the record by months:

| Month | Fires |

| May | 7 |

| June | 64 |

| July | 185 |

| August | 24 |

| September | 39 |

| Total | 319 |

Three fires were man-caused. The area burned was 722 acres.

Smokejumping became practical in 1940. Experiments were first conducted in Region Six, but the next year the project was transferred to Region One. Ralph Hand was in charge, but Frank Derry was the technician that developed the padded suits, helmets and remodeled the parachute. Smokejumping had been thought of years before it was tried, but was considered too dangerous.

The use of smokejumpers caused the first reduction in the number of lookout points manned. The points which added little to the detection system but were manned to give smokechaser coverage were the first to go.

In the first few years of smokejumping the men were trained at Seeley Lake and then stationed at landing fields on the forest such as Moose Creek, Cayuse Creek and Seeley Lake. Experience proved that better use could be made of the smokejumpers if they were more centrally located. They were then stationed at the Remount Depot and then finally in Missoula.

1943

World War II drained the young, able-bodied men into the armed services. The Forest Service had great difficulty in getting enough men to man the lookouts, fight fires, and get its other work done. There were still some young men available and this was one of those rainy summers when no one worried much about fires. So in spite of the handicaps everything went along quite well.

1944

This year the manpower shortage was severe. The Forest Service employed women and 17 year old youths to operate the lookouts. The women were generally better lookouts than the 17 year olds who had never been away from home. Most ranger districts had at least one woman lookout who would get all the lookouts on the telephone and tell them what to cook and how to prepare it.

The blister rust crews were mostly 17 year olds but there were some Mexican Nationals that were contracted by the U.S. to help meet labor needs. They worked on the farms in the spring and then went to work for the Forest Service fighting fire, etc. These were some of the toughest men physically I have ever seen. They knew how to use firefighting tools, could take the heat and had great physical endurance.

Some work camps were made up of internees. These were men who were in the United States from enemy countries who were not citizens when the war was declared. They were very good workers and most of them desired to be come U.S. citizens. Their numbers were rapidly decimated by their acceptance into the armed services.

Conscientious objectors who volunteered for forestry work were used as smokejumpers. They developed into a very good outfit.

The fire season of 1944 was not severe so the Clearwater Forest got a long very well.

Airplanes were used to scout large fires as early as 1926. They were also used after lightning storms to fly over the forest scouting for fires, but the use of airplanes for the detection of fires on a planned basis that combined lookout coverage and airplane detection started in 1944. These plans were prepared by Ralph Hand and Herb Harris. This system was first tried in the Bob Marshall Wilderness Area. It was so successful that it was soon adopted by all forests, and a big reduction in the number of lookouts and the miles of telephone lines followed.

1945

In 1945 the manpower situation was about the same as 1944 except by this time German prisoners of war were added to the firefighter crews. There were too many restrictions on their use to be effective.

The season was quite severe and manpower was so scarce that it became necessary to use soldiers to fight fire. A fire started in a snag patch in Little Washington Creek and burned to the river. Almost all of this fire was in 1919 burn. Soldiers were used, but they fought fire reluctantly. Soldiers have been used in fighting fires in 1910, 1919, 1926, 1944 and 1945.

During the war the Japanese hit upon an ingenious device to drop bombs on the United States. This was a paper balloon that rode the jet stream across the Pacific Ocean. It was equipped with sandbags and a barometer so that when the balloon dropped to around 10,000 feet a sandbag was released and the balloon went back up to around 15,000 feet. There was also a timing device on the balloon that set off the mechanism to start dropping bombs when they estimated the balloon would be over the United States. When the bombs were all dropped a charge of explosives went off that demolished the whole apparatus.

These machines were first released in the fall of 1944. It was given great publicity in Japan and was a morale builder for a nation which had began to realize that going to war against the U.S. was a mistake. The military knew about this as soon as it was started, but at first the Forest Service learned about it was when Forest Rangers and local people began reporting strange flashes in the sky. Then a balloon that failed to function properly landed near Kalispell. This news made the local papers but was quickly hushed.

In January 1945 there was a Fire Control meeting in Washington D.C. at which I represented Region One. At this meeting the Army told us all it knew about this bombing, but cautioned us to keep it secret so that the enemy would not know what success they were having. They explained the device and showed us a map where all known bombs had landed. They had also tracked many of these balloons by radar and had plotted their paths on the map.

The balloons took a generally eastward course reaching North America all the way from California to Alaska. Their timing of the bombs was poor because most of them fell in the Pacific Ocean. All the bombs recovered were the anti-personnel type. These were designed for use against cities, but with coming summer it was feared that the Japanese would switch to incendiary bombs. However, the bombs were so widely scattered and doing so little damage that the military did not plan any action to shoot the ballons down unless the situation became more serious.

I returned to Region One and visited each forest where I explained what was happening and emphasized secrecy. I had barely returned to Missoula when a Senator got his name in the papers by telling the newsmen all about it.

Actually these bombs did little damage. One balloon hung up in a tree on the Pacific Coast where some picknickers found it and touched off a fatal blast by tampering with it. In Region One pieces of the paper from the balloons were found on the Nezperce, Colville and Deerlodge National Forests. A bomb landed in a field near Darby, Montana. So far as is known none hit the Clearwater although some claimed a fire was set by a bomb. The Japanese quit sending the bombs in April 1945. I never heard why. Some said the Air Force bombed the launching site, but others said, and I believe this is correct, that the Japanese decided the project was a failure.

Of course no one knew that the Japanese had quit sending out balloons. That summer the planet Mars could be seen with the naked eye in the daytime. It was reported as a balloon so many times to Fred Fite, the Regional Dispatcher in Missoula, that I calculated for Fred its azimuth and vertical angle for each fifteen minute interval during the day.

At the Bungalow there was a guage for measuring the flow of the river. One of the parts of this meter was a float that moved up and down in a pipe as the water rose and fell. It was a tube about 18 inches long and pointed at each end. On its sides four strips of metal were welded to serve as guides and reduce friction. It did look a little like a bomb. The machinery that recorded the river flow was housed in a small building about the size of a telephone booth. There was an extra float in this building.

One day George Pollock, Headquarters guard, had occassion to open this building. Olie Bowlin, the packer, was with him and saw the float. He asked Pollock what it was. Pollock told him not to touch it because it was a Japanese bomb that one of the men had found out in the woods and had put it there for safe keeping until some Army man could come and get it. He warned Bowlin to keep it a secret.

Several days later the man who serviced the meter came and Bowlin felt it was his duty, since Pollock was absent, to warn this man to use due care because of the bomb. The man unlocked the booth and peeked inside. He could see no bomb. When Bowlin showed it to him the man said "Oh, that". Then he picked it up and tossed it to Bowlin. For an instant Bowlin almost had heart failure, then he realized that he was the butt of a joke.

1961

This was a very dry fire season and the Clearwater was engaged in fire fighting from the first of August until about the 25th. This was one of the few years that the Clearwater Forest had difficulty with man-caused fires. There was also a shortage of firefighters. Actually this was a Regional problem brought about by three fires on the Clearwater occurring at the same time as two on the Nezperce and a very bad fire on the Bitterroot.

The Clearwater had fires in the Musselshell area, one at Ashpile Creek, Cayuse Creek, Gravey Creek, Orogrande, and Surprise Creek in the Wilderness Area. The total area burned was 12,625 acres of which 2,822 were in the Wilderness Area.

1967

This was another dry season. Fortunately there were few lightning storms so the occurrence was low. Sneak Point, a logging fire, burned about 1400 acres and there were two fires in the Wilderness Area on Cliff and Warm Springs Creeks that burned about 1100 acres.

There have not been any severe fire seasons since 1967.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

clearwater/story/chap16.htm Last Updated: 29-Feb-2012 |