|

The Clearwater Story: A History of the Clearwater National Forest |

|

Chapter 18

Mining

One of the most important historical events in the Clearwater country, or in all Idaho, was the discovery of gold at Pierce in 1860. This discovery triggered the first rush of white men into Idaho. Pierce, as well as the richest placer areas, was outside the present Clearwater National Forest. There was a lot of placer mining in Armstrong Gulch and the Rosebud drainage. Every small creek was sluiced out, and you can still find parts of the old mining ditches. While clearing ground for mining in this area a fire, or fires, escaped and burned over most of the Rosebud drainage and the head of French Creek. The upper basin of French Creek was mined by a group of Frenchmen who later worked this area over a second time.

Rhodes Creek was the richest of all the placer areas around Pierce. Preacher and Clearwater Gulches are the only parts of Rhodes Creek on the National Forest. Pat Gaffney, who later became well known in the Weippe country, had a claim on Clearwater Gulch.

In what is commonly referred to as the Musselshell Country, Mike White mined on Lolo Creek. Henry Greer and "Daddy" Cole had claims on Musselshell Creek. It was these two men who dug the tunnel through which the creek flows. It was to drain a basin above so that it could be mined.

Gold mining in the Pierce area went through three stages. These stages did overlap, but in each stage one type of mining was clearly dominant. The first was the placer stage which was dominant from 1861 to 1892. Placer mining is the process of separating the loose gold from the gravel and clay by washing.

The second stage was finding the lode claims and mining the ore. This method required a stamp mill to grind the ore and separate out the gold. These stamp mills were heavy, but they were taken into some of the most difficult places. This stage ran from 1892 to about 1910. In general, this kind of mining was not very successful in the Pierce country because the veins of ore were small.

The third stage was dredging. Dredging started in 1906 and ended in the 1930's. The dredge mechanically did the same work as the placer miner, but more efficiently.

There were a large number of lode claims (at least a hundred) located in the Pierce Mining District, but only a few showed enough promise to be developed. Here are the names of those I remember: (This list is incomplete.) In the Bald Mountain country were the Mascot and the Democrat. The American Mine near the mouth of McCauly Creek was both a lode and a placer claim. On Lolo Creek and inside the Forest was the Pioneer. The Dewey on Musselshell was inside the forest. There were several in the Rhodes Creek drainage, but all I can recall were the Ozark, the Crescent, and the Wild Rose. The latter was inside the Forest. On Orofino Creek and inside the Forest was the Rosebud. I believe this is the claim now called the Red Cloud. Inside the Forest on French Creek was the Klondike. Then further from Pierce was the Oxford.

Several dredges operated outside the forest boundary. There may have been a few acres dredged in Rhodes Creek. The dredges first operated close to Pierce, then Canal Gulch. Later Rhodes Creek, the American Mine and small areas in Orogrande were then dredged.

Moose City

Gold was discovered at Pierce on October 1, 1860. Miners and prospectors flocked to the locality in 1861. The majority of the miners came from California and were experienced prospectors. They not only understood how to mine gold, but also knew the best ways of prospecting the streams. Using Pierce and Lewiston as bases, the prospectors spread out in all directions over the mountains. During the summers of 1861 and 1862, all the major gold deposits in the Clearwater drainage were discovered and all its major streams thoroughly prospected.

Gold was discovered around Moose Creek and Independence Creek by a wandering band of prospectors July 4, 1862. This placer ground paid its discoverers well for a short time but was soon deserted. The rich deposits were limited. Independence Creek was dredged in the 1930's.

A second population influx was stimulated in the late sixties by discoveries made by prospectors Ernest Hilton, William Shepard and Tommy O'Brien. It is said that fully two hundred people rushed to this locality. This boom resulted in the founding of Moose City with a saloon, restaurant, hotel, jail, butcher shop and three general stores. For three years the diggings produced well and supported the population. But during the seventies the diggings began to fail again. Moose City was soon abandoned, though a few people continued to mine there for many years.

There is still some prospecting around Moose City and people pan the creeks to pick up a few "colors", but there are no mines being operated. Until 1924, parts of the old jail could still be seen, but shortly thereafter the Forest Service built a work camp on the site of old Moose City. Men from this camp tore the old jail apart. Today nothing remains of old Moose City except a few level spots where buildings once stood. A thick stand of young timber has reclaimed the old town and the diggings. Moose City is hardly noticeable now, even when you stand at the Forest Service sign that marks the place.

William Rhodes and the Blacklead

William Rhodes symbolizes the gold mining industry in the Clearwater country. Rhodes either joined in the party that went to Pierce with Captain Pierce in late 1860 or he arrived early in 1861. He became quite wealthy for his time, but as the placer gold around Pierce was worked out his for tune faded. Later, with the boom of lode claims in the Pierce country, Rhodes again came to the Clearwater country and tried to develop a lode claim. He died while he was thus engaged. It was but a few years after this time that lode mining in the Pierce country practically came to an end.

William Rhodes, or Billy Rhodes as he was commonly called, was part Negro. Some accounts say that he was one-eighth Negro. He was sometimes called "Blackie" Rhodes which would indicate he showed his Negro ancestry strongly. He was a large bony man with black, curly hair which, in his later years, turned snow white. He was characterized by Jauquin Miller as "a manly mulatto of great honesty and good sense". He was not a drinker or a gambler. However, when he had the money he was overly generous. Everyone had a good time while Rhodes had money.

Billy Rhodes came to California in 1849 with a Jones family from Missouri. He went to northern California, mining near Scott's River. He proved to be a very successful miner and became something of an expert. He joined in the early gold rush to Idaho and arrived in old Oro Fino late in the fall of 1860 or early in 1861. He staked some claims or a claim on Rhodes Creek which took his name. Rhodes apparently picked the richest ground in the Pierce locality. He worked the mines around Pierce in 1861 and 1862 and, according to newspaper reports of the time, left in 1862 with $80,000.

From Pierce, Billy went to Arizona where he engaged in prospecting for a lode claim. He found one and sold it for $75,000. In spite of this wealth, Rhodes returned to Pierce and Lewiston flat broke. He prospected around Pierce without success. He also cooked for a cattle ranch in the Salmon River country. Such, however, was the reputation of Billy Rhodes to find gold that John Silcott and John Risse of Lewiston furnished him a grubstake and equipped him for prospecting.

The remainder of this account is taken from several sources. I have talked with Ernest Hansen who prospected the Blacklead country for several years from about 1902 to 1914 and had heard many stories about the death of Bill Rhodes and knew the country well. Another old timer I talked to was Walter Sewell who knew Frank Altmiller, Sr. very well and had heard his story from him. Frank Altmiller, Jr. also told me his father's story as told to him many times. I have also read Sister Alfreda's account as taken from a scrapbook of A.F. Parker which had an article in it taken from a Lewiston newspaper.

These stories differ so I have here tried to coordinate them, but in case of conflict giving greatest weight to Frank Altmiller's story. The stories of Frank Altmiller, Jr. and Walter Sewell come closer to agreeing than do the others, which is to be expected.

In the spring and summer of 1886 Billy Rhodes teamed up with Jerry Johnson, with whom he had mined before, and another man, probably Zachery, and they went prospecting in the head of Cayuse Creek. There they discovered the silver ore deposits around the Blacklead Country. Jerry Johnson and Zackery were not interested in a lode claim. They knew that it would take a great deal of money to develop a mine in such remote country, so they would have nothing to do with anything except placer gold.

However, Billy Rhodes returned to Lewiston and reported his find to his backers who became quite enthusiastic. John Risse sent his brother-in-law, Frank Altmiller, who was 18 years old at the time, and Silcott hired Hass Crane to go with Rhodes and start developing a mine.

They packed into the Blacklead Country and had barely time to build a cabin before winter arrived. In that high country snow came early and in short time was very deep. Fortunately, Crane had the good luck of killing a very large mule deer before the snow came.

They went to work on an inclined tunnel at a spot picked by Rhodes as the most likely to lead to a body of ore. Contrary to modern day rumors they did not find anything very promising.

Shortly after Christmas Rhodes had an attack of dysentery. His companions at first did not consider his condition serious, but he gradually grew worse. Crane and Altmiller worked on the tunnel and Rhodes did the cooking.

One day, about the first of March, Rhodes told Crane and Altmiller to go to work on the tunnel and he would cook lunch for them. When they returned to the cabin at noon they found him lying dead on the bed. They buried him in the snow which was about fifteen feet deep. Crane and Altmiller knew little about mining so they stopped work on the tunnel and concentrated on cutting wood, playing cards and looking for game to stretch their supplies which were running low and now consisted only of flour and beans. Crane killed a lynx. Then in April they found a bear in his den. They killed the bear and it furnished some badly needed meat, although their dog refused to eat it.

About June 1 the snow had melted some and bare ground appeared in the path of the snowslide of the previous winter. There they buried Billy Rhodes, marking his grave with a pile of stones. Then they decided to try and make their way to Pierce by taking a downstream route. The Lolo trail, their route in, was still covered with snow.

They dropped down to Cayuse Creek where the snow was gone. There they came upon an Indian pony which had been there all winter so they called the creek "Cayuse", and so it is today. They then went downstream to the mouth of Orogrande Creek and out to Pierce. They made the trip in about ten days. Some prospectors went back to the Blacklead in the summer of 1887 to see what Billy Rhodes had found and to see that he was properly buried.

Interest in the mineral showings in the Blacklead country continued. Lafayette (Lafe) Williams, a banker at Lewiston, had some claims and a cabin at the Blacklead. He gave the mining area its name. Just when he took his claims is unknown, but the map of 1898 shows Williams Peak which was named for him. Then there were the Hansen Brothers, five of them, who came to the area in 1902. They also had a cabin and did considerable work on a tunnel trying to find a larger and richer body of ore than was apparent on the surface. There were a number of people who had claims such as Walter Sewell, John Austin (not the trapper) and others.

There was a mining engineer named Charles M. Allen who lived near the town of Lolo, Montana. He had worked for the Anaconda Copper Mining Company. He was a geologist and a mining expert. Perhaps he enjoyed going in the woods, but he may also have been looking for Isaac's mine. At an old campground a short distance below where Jerry Johnson's cabin had been, there was a pine tree that had been blazed. On this blaze was inscribed "Camp Allen 1896". This tree was felled when the Lewis and Clark Highway was built but Ranger Puckett removed the section of the tree that carried the inscription and took it to Powell.

At the request of Lafe Williams and the Hansens, Mr. Allen examined the Blacklead country in 1914. He stayed with the Hansens for two weeks and carefully went over the area. He also examined many of the prospect holes. He finally told Williams and the Hansens that, in his opinion, they were wasting their time and money. Williams and the Hansens quit the area, but there still is a great deal of prospecting in the Blacklead country. No serious attempts have been made to develop a mine.

Many stories are told about Rhodes' lost mine and how rich it was and about the tons of rich ore the Hansens packed out, but there is no truth in any of these tales. Ernest Hansen told me that all the ore was low grade silver and that no one ever took out more than a sample. If anyone is interested enough in the facts, he can come and get me and I can take him to Rhodes' tunnel (that is all it was), his grave and the rock foundation of his house which burned in 1910.

|

| A.N. Cochrell at the site of Billy Rhodes' grave, 1956. |

|

| Lafe Williams in front of his Blacklead cabin in about 1915. |

|

| The Williams cabin in 1956. |

Jerry Johnson and the Lost Mine

On September 26, 1893 the Carlin Party reached the Lochsa River a short distance below the mouth of Warm Springs Creek. They were surprised to find four men there. Two were hunters and departed for Montana the next day. The other two were Jerry Johnson and Ben Keeley. They were building a cabin and planning to stay during the winter.

In his book "In the Heart of the Bitterroot Mountains", Himmelwright has a chapter on "The Lost Indian Prospect and Jerry Johnson". He writes:

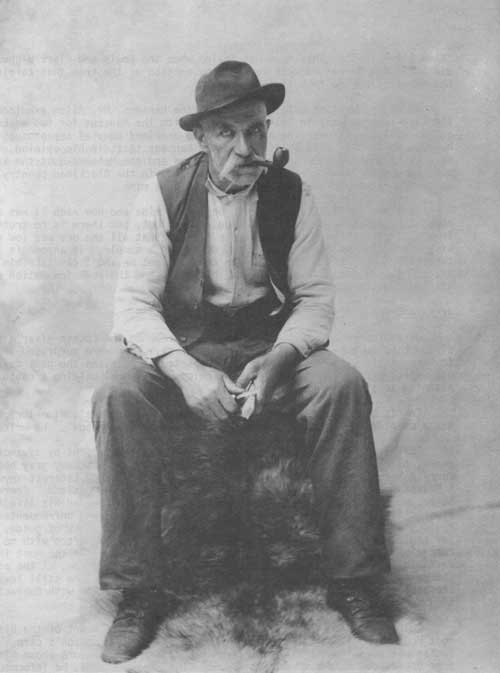

"Six feet in height, with a powerful frame slightly bent by advancing years, black hair mixed with gray, jet black eyes, and a stubby gray beard, Jerry Johnson, the prospector, would arouse curiousity and interest anywhere. A Prussian by birth, he emigrated at an early age to New Zealand. There he became interested in mining, and since then he has devoted his life to prospecting for the precious metals in the wildest and most unfrequented regions of the earth, and occasionally acting in the capacity of guide, hunter and packer. Enthusiastically devoted to his work and often with no other companion than his faithful dog, he has searched for gold in the most inaccessible regions of the Cascades and Rocky mountains, and now, at the advanced age of 60 years, rugged from hardship and exposure, he still loves the isolation and solitude of the mountains, and is seeking with characteristic perseverance the long lost Indian Prospect.

"Many years ago, while Johnson was encamped in the heart of the Bitterroot Mountains, a half-starved Indian found his way to Johnson's camp. The Indian was given food and shelter, and grateful for the favors shown him, before departure, in broken English and by signs and gestures, he informed Johnson he knew where there was "Heap Elk City, heap Pierce City", meaning much gold, there being mines at the places named. Johnson at once engaged the Indian to guide him to the place.

"Returning to the nearest point where supplies could be purchased, he secured adequate equipment, and with one other man and the Indian started back into the mountains. The route taken by the Indian was along the Lolo trail to the warm springs. Here the Indian fell sick, but the party pushed on fifteen miles farther east to a small prairie which Johnson calls "The Park". When they reached this point, the Indian became so sick he could proceed no further. Fearing he might die, Johnson got the Indian to tell him how the gold was found. This was quite difficult as the Indian could speak few words of English and had to convey most of the information by gestures. The story he told was substantially as follows:

'A party of Indians were camped at the place they were journeying to, some years previously, and one of them being suddenly taken very sick, a "sweat-bath" was prepared for him. (Here the author describes the making and use of a sweat house.)

'While preparing this sweat-bath, it was necessary to loosen and remove some white rock and while doing this, the Indians discovered that the rock was full of gold, or, as the Indian called it "Elk City".

'The Indian guide grew worse and weaker every hour, and Johnson being alarmed, took him in his arms and carried him to a more elevated position, where a view to the eastward could be obtained.

'Which way from Here?' Johnson Asked.

'With his remaining strength, the Indian raised his arm and pointed to a peak covered with snow. "See snow", he said. Then raising one finger, he pronounced the one word "sun" and rolled over on his blanket exhausted. A few hours later he died.

"Not discouraged by his ill fortune, Johnson and his companion buried the Indian and pushed on to the peak indicated to him and searched the country beyond and around the peak all that summer, but never succeeded in finding the old Indian camp. Since that time he has spent several summers fruitlessly in the same neighborhood, and is now passing the winter in that desolate snow bound region, hoping, early in the spring, to continue his search for the "Lost Indian Prospect."

Such is the story of Isaac's mine. I have heard various versions of it but this is the oldest and came directly from Jerry Johnson so I presume that it is the most authentic. Isaac's complete name was Isaac Hill. He came from a family of white, Delaware and Nez Perce origin which lived near Kooskia. His grave has become somewhat lost, but a map I have which was made in 1894 shows his grave on top of the ridge about one and a quarter air miles southeast of Tom Beall Park.

A lot of people have searched for Isaac's mine. Ben McConnell, Joe Ebberly and Bill Parry, early day Forest Rangers, it is said, looked the country over thoroughly. There were many others that did the same.

Another story that ties in with the Isaac's Mine is that years ago some Indians were camped at what is now called Gold Meadows. They had some gold but refused to say where they had found it. That is how Gold Meadows got its name.

Jerry Johnson spent his old age in the Missoula vicinity and is buried at the Missoula Cemetery.

|

| Jerry Johnson (Photo courtesy Montana Historical Society) |

|

| Jerry Johnson cabin in about 1902. |

OTHER MINES

In the days of Moose City some gold was placered out of California Creek in the extreme head of the North Fork of the Clearwater River. Then in about 1911 an attempt was made to develop a lode mine under the name of the "Clearwater Gold and Copper Co." There was considerable activity for about 10 years, but the ore was so low grade that the operation was halted. The last time I was at this mine the buildings were in bad condition and there was no sign of fresh work.

Pete King placered some gold out of Pete King Creek at his homestead. There were some other placer operations further up the creek. Pete King came into that area about 1890. There is a lode claim on Higgins Hump above these claims.

In recent years there has been some discussion over the possibility of developing a Kyanite mine in the area around Woodrat Mountain. A Louisiana firm held a claim in the area, but has since let it lapse.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

clearwater/story/chap18.htm Last Updated: 29-Feb-2012 |