|

Early Days in the Forest Service Volume 3 |

|

By George S. Haynes

(Retired 1951)

I went to work in Region 1, on the Coeur d'Alene Forest, about May 1, 1923. I had worked several years in Region 2. The late Theodore Shoemaker hired me as forest guard the spring of 1916 when he was supervisor of the Pike Forest in Colorado. He assigned me to John H. Patterson, Forest Ranger at Colorado Springs. Mr. Patterson was a remarkable man with the qualifications needed to be a good Ranger. I mention these two men because they gave me my first training in Forest Service work, policies and regulations. Their enthusiasm for their work and their high standards of service had a lasting influence on me during my thirty-five years with the Forest Service.

Charles K. McHarg was supervisor of the Coeur d'Alene and St. Joe Forests with headquarters in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho. James F. Brooks was assistant supervisor on the Coeur d'Alene Forest.

The late Philip Neff was logging engineer. I was assigned to the Little North Fork Ranger District. This was a valuable white pine district with large timber sales which were handled by project sales men who were under the supervision of the logging engineer. There was lots of Northern Pacific land grant patented land and quite a number of timber homestead patents.

The Rose Lake Lumber Company, which became the Winton Lumber Company in 1924, were driving their logs to Coeur d'Alene Lake. They purchased the Northern Pacific patented land and timber about this time. The Ohio Match Company were getting prepared to log the Burnt Cabin drainage by railroad. Only white pine was considered merchantable at this time. Mixed species were used for camp and improvement construction.

The Ranger Station was at Honeysuckle which was located near where Skookum Creek empties into the Little North Fork of the Coeur d'Alene River. This is about a mile below where the Deception Creek Experiment Station is located. The Rose Lake Lumber Company had a camp and a warehouse across the creek from the Ranger Station. There was a one-track road with turnouts from Wolf Lodge to Honeysuckle. This road was built by the Forest Service and the Rose Lake Lumber Company. Much of the grade was eleven percent. The Rose Lake had a tote road to Camp 6 on Lieberg Creek, a distance of nine miles. The Forest Service had a good pack trail from Camp 6 to the Magee Ranger Station. The Magee Ranger District supplies were packed from Honeysuckle, a distance of seventeen miles. There were a few primitive trails which had been built by the Forest Service, homesteaders, prospectors and loggers.

There was a two-room log cabin and a small log toolshed at Honeysuckle. Water was carried from Skookum Creek. When Camp 10 was built a mile and a half up Skookum Creek, we dug a well with a pick and shovel near the cabin. Instead of the old oaken buckets, two five-gallon, gasoline cans were used to bring the water up. This well was replaced by a gravity system in 1930; $328.00 was allotted for this project. This was all spent for water pipe. The labor was all contributed time. There were four lookout points which had telephone connections (grounded tree line). Chilco Mountain had a cabin. The other three points, Spades Mountain, Lookout Ridge, and Monument Mountain had no improvements. A shake barn at Horseheaven was used as a fireman station.

The crew consisted of Ranger alternate and station fireman at Honeysuckle, a smokechaser at Horseheaven, a lookout on Chilco Mountain, a lookout-smokechaser on Spades Mountain, a lookout smokechaser on Lookout Ridge, a lookout smokechaser on Monument Mountain, a ten-man trail construction crew, and usually two or three men on telephone maintenance or construction. The telephone and trail men were the second line of defense on fire suppression. The smokechaser pack weighed thirty-four pounds without drinking water or blanket. The rations were supposed to last three days. Travel time was two or three miles per hour on trails, and about one mile per hour through brush or reproduction. After the first four or five miles, the weight of the fire pack seemed to increase. If fire conditions became severe, two or three emergency men might be added. A forest pack string would pack the season's supplies to the lookout points about the middle of June.

Most of the Ranger's time was spent in the "brush," training and inspecting on the job, "ramrodding" the trail and telephone maintenance and construction, chasing smokes, packing and doing anything that needed to be done. The alternate's work was about the same as the Ranger's. During the fire season, it was considered a good practice for either the Ranger or alternate to be at the Ranger Station to do the fire dispatching and to take immediate action on all fires. Getting good, quick action on all fires was imperative to prevent large fires. This required good, experienced men on lookout points and a communication system that worked at all times. The lookout-fireman positions required men with special qualifications who were willing to work twenty-four hours a day and seven days a week. There was no overtime paid or compensatory time allowed. Getting and keeping these men for the field season of four to six months was probably the most important job that the Ranger had.

Cooperation was a must in all National Forest activities but especially in fire prevention and suppression. The timber sale men, slash disposal crews, research, blister rust, insect control, and logging crews worked on fire suppression when their help was needed.

There were three main sources of fire on this District: lightning, logging operations, and campers. Lightning caused the most fires and usually required the most travel time. Slash on the logging areas was the fastest burning and the most hazardous. It was impossible to keep all the slash disposed of currently. The Ohio Match Company were cutting about 18 million feet and the Wintons about 40 million feet per year, in many different drainages. Safe spring burning was almost impossible because of hangover fires in the deep duff. Some falls were too dry to burn until late in the season, other falls were too wet. Consequently, there often was much old and green slash that was a potential threat through the fire season. There was lots of girdled hemlock on many of the old sale areas.

Many of the Winton men had been through the bad Minnesota forest fires where there had been so much loss of life and property. They were very strict about smoking in the woods when the fire season was bad. The timber sales contracts and other agreements with the Forest Service required a fire patrolman on each sale area during the bad fire periods.

If a patrolman turned a man in for smoking in the woods, he might be fired or warned once; the next time, he was paid off. Mary men chewed tobacco or used snuff during the fire season.

The Forest Service handled the slash from the logging on the Winton private land under a co-op agreement at a rate of from forty to sixty cents per thousand, about like the states handle private slash now. In heavy stands, the cut was often over 40 thousand feet per acre. This would often cost the Wintons over $20.00 per acre. They traded many cut-over sections to the Forest Service for around $1.00 per acre. Much of this land had 10 or 15 thousand board feet of mixed species per acre on it. As there was no market for mixed, the Wintons only logged white pine. They considered it good business to dispose of the cut-over land because of the fire responsibility, taxes and other costs. However, they felt that after they paid so much for slash disposal, they should have received more per acre for their cut-over land that had such good stands of mixed timber.

Phil ("Bronc") McManamin was their woods boss, Wm. Keeler their woods superintendent, and Walter Rosenberry their general manager over all their woods and sawmill operations. These men were high-quality citizens, good timber men and wonderful cooperators. "Bronc" always rode a good horse in the woods operation and between camps. He was really a mounted patrolman always on the alert for any kind of fire cause or danger. The best recreation camp areas along the river were on Winton land. They did not object to the public building camp fires on their land if care was used and safe fire requirements met. The same applied to the huckleberry pickers. There is no way of estimating the value of the help this company and their employees gave to fire prevention and suppression during the eleven years that I was Ranger on this district. During the twenties, this district and most of the forest was closed to public travel when the fire season was serious. After more roads were built, making transportation faster and easier, the closing regulation was used very little except in certain areas of high hazard.

A good trail was built up the river a few miles in 1923. Many good pack trails were built during the next five years. A road was pioneered into Magee the fall of 1927 and finished in 1928. Improvement money was very limited prior to 1932. Telephone lines and lookout stations were given first priority with this money. Much of the labor was done by contributed time when the weather and fire conditions permitted. A cupola log cabin was built on Monument Mt. in 1924. A similar cupola log cabin was built on Lookout Ridge in 1926. A 50' lookout tower was built on Spades Mt. in 1926 and a fireman cabin for living quarters for the lookout in 1928. It took six seasons to get these improvements. Almost all the labor was done by contributed time. These improvements were of much importance to the fire protection of this Ranger District and adjacent Ranger Districts. A 30' tower with a 14' x 14' lookout house was built on Jacknife Peak in 1931. The same season, a frame fireman cabin was built at Horseheaven. A 30' tower with a 14' x 14' lookout house was built on Bumblebee Peak in 1932. The same size tower and lookout house was built on Wall Peak in 1933. A log fireman cabin was built on Tepee Summit in 1933.

From 1923 to 1932, the following improvements were built at the Ranger Station. The amount of money allotted for them is also shown. All the labor was contributed except a small amount on the garage. Most of the work was done after the field season. Much of the lumber was not planed and was salvaged from the old Winton flumes, abandoned scaler cabins, and other buildings.

| Year Built |

Building | Money Allotted |

Material Purchased |

| 1923 | Log warehouse | $100.00 | nails, cement, shingles |

| 1926 | Root cellar | $125.00 | cement, shingles, nails |

| 1927 | Bunkhouse | $150.00 | cement, shingles, nails, siding, windows, paint |

| 1929 | Barn | $100.00 | nails, lumber |

| 1930 | Water system | $328.00 | water pipe |

| 1932 | Garage | $340.00 | all new material |

The fire story on this district for these eleven years is the story of handling small fires under tough pre-road conditions. It will require another article to tell it.

The old days were a challenge to all the Forest Service personnel from the Chief to the newest employee. The future has just as large and important challenges in growing a sustained yield of timber and administering the best possible multiple-use program.

An Attack on the Dendroctonus Monticolae - Spring of 1930

This historical item is being written approximately twenty-nine years and seven months after the reports were sent in and the equipment, commissary and supplies accounted for June 30, 1930.

This attack applies to the Little River District of the Coeur d'Alene National Forest. This district was deceased in 1934. Prior to its passing, it had been active in "White Pine doings." Even before the Coeur d'Alene Forest was created, the Dendroctonus Monticolae (Mountain Pine Beetle), prospectors, trappers, homesteaders, fishermen, the Northern Pacific Railway and various logging companies had shown a deep interest in this area, especially in the valuable stands of white pine timber.

The Ranger Station at this time was located on the Little North Fork of the Coeur d'Alene River near the mouth of Skookum Creek. It was called Honeysuckle.

The "bugs" had been living on the best of white pine for many years. James C. Evendon and his crew had been checking on them for a number of years. Their surveys showed something needed to be done or the bugs would get most of the white pine before the loggers could harvest their share of these valuable trees.

Mr. Evenden and Charles K. McHarg, Forest Supervisor, had recommended that government funds be made available for control measures to decrease the number of active bugs on the Coeur d'Alene. In this, they had the support of Evan W. Kelley, Regional Forester, and Elers Koch of Timber Management, and $150,000 was allotted for this work, which had to be completed before June 30, 1930.

Clyde S. Webb, who had been in charge of the insect control project on the Beaverhead and Bitterroot Forests in 1929, was assigned to take charge of this insect control job. About the first of March, Webb arrived in Coeur d'Alene. He and Evenden immediately got their heads together and decided to throw everything (and everybody) into this attack on the Mountain Pine Beetle.

Evenden and his men had made a fairly intensive field survey of the infestation the fall of 1929. They had the heavily infested areas mapped and camp sites shown. Control work was to be done on four Ranger Districts. The other district headquarters were Carter, Pritchard and Magee.

The snow was still deep, especially on the north slopes and high ridges, and had to be plowed for eight miles to get into Honeysuckle. Considerable road maintenance would be necessary to get trucks into Magee. These back stations were not usually opened up until about the middle of May. This would be too late to complete the work before the last of June. This meant that we would be "crowding" the snow on these areas most of the time.

The Winton Lumber Company log drive was on. They were taking men and supplies to the pack station on the Wolf Lodge Road. The men would walk the rest of the way, and supplies were taken on by pack string. The snow was from six to eight feet deep over the summit and in other places. Frank Hicks ran the stage that took the men. On March 12, I went on this stage, then walked to Honeysuckle and on down the river to Winton Camp 14. The snow at the lower elevations was from two to four feet deep. The next day, I looked over road and telephone lines to below the Lieberg Dam. It would take at least ten days and maybe three weeks of thawing weather before the road could be opened up so that equipment, hay, grain, food and men could be brought in by truck. March 14, I returned to Coeur d'Alene.

The etomological part of the job presented a variety of conditions in the different areas. Jim Evenden had Tom Terrell, Archie Gibson, Henry Rust, and probably others who worked on the technical problems, and who helped in training of spotting crews and doing inspection and checking.

Howard Drake, Tom Crossley, Dan Maryott and others of the Coeur d'Alene timbermen spent most of their time on this control project, at least until it got well under way. Webb brought a number of experienced bug men with him. It was necessary to get quite a few camp bosses, chief spotters, crew foremen, packers and cooks from other forests. A certain amount of training was a must. This could not be done in a large group because the men were being put to work whenever there was camp room, and camp facilities were limited and scattered.

There were many problems to solve in getting a good, effective control job done between the going off of the snow and June 30th. One objective was to install every camp as early as possible. The snow conditions made opening up to the trails and repairing the telephone lines difficult until the snow had gone down to about eighteen or twenty inches in depth. On some camp sites, it was necessary to shovel out the snow before the tents could be put up.

On March 31, I went to Honeysuckle to open up the Ranger Station and to get storage space ready for the equipment, food supplies, hay and grain that would be coming in as soon as the road was plowed through. Stanley Sanderson, Assistant Supervisor, was supervising the opening of the road to Honeysuckle and to Magee - snow plowing into Honeysuckle and heavy maintenance on the road to Magee. Tom Crossley came in to check the snow conditions and to help get the work started. Phil Clack helped here for some time too.

On April 1st, Jimmie McIntyre, of the Winton Lumber Company, Crossley, Les Gossage, and I went to Leiberg Creek to look over an infested area along the river. The Winton rear of the log drive was still upriver. The Wintons agreed to take all the infested trees that they could handlog into the river before the rear of the drive was past this area. Gossage did the spotting ahead of the sawyers and supervised the slash disposal. These were the only sawlogs salvaged on this district of all the trees cut and treated in 1930.

The road was opened April 3rd. The trucks came in with the first loads April 4th. John F. Shields arrived April 5th to handle the headquarters clerk job. He was probably the busiest man on the district with equipment and supplies coming in by truck and going out by pack string, orders from the camps coming in, reports to make and many other things to supervise and do.

The pack stock came in April 7th. On April 8th, the Cathcart camp was packed in. John T. Horner was in charge of this camp. Ed Sathers was in charge of the crew working on bugs in the area around Honeysuckle. The camp at the mouth of Tom Lavin Creek was packed in April 16th. Joe B. Gotz was in charge of this camp. It was necessary to shovel out about 18 inches of snow before putting up the tents. Floyd M. Cossitt and I looked over part of this area. We found many bug trees, some with fully developed bugs, others where the bugs appeared to have emerged the previous fall, others were just in the larvae stage. There seemed to be all stages and conditions of bugs. A distress call was telephoned in to Jim Evenden. He arrived the next day to look the situation over. He was surprised to find the pack trail so muddy and the bugs in so many stages of development, with two feet of snow on the ground in many places and the calendar reading April 18th. His official opinion was "The situation is abnormal as there should not be any mature bugs so early in the season." The fall before had been warm and sunshiny. It was assumed that the weather conditions had developed them prematurely. We were very glad to get Jim's help in solving this problem and many others.

The Cascade Creek camp was put in about April 20th. Snow had to be shoveled before some of the tents could be put up. Floyd M. Cossitt was in charge of this camp. The Iron Creek and Barney Creek camps were put in about the first of May. Glen Dodge was in charge of one of these camps, and James Sabin the other. These two areas did not have as many infested ties as the survey showed. All the other areas overran the survey estimate. One of these camps was moved to three miles above the Tom Lavin camp about the first of June.

All of these camp bosses were extra-good men. However, the days were not long enough for them to do all the work necessary. It took lots of early and late effort for them to keep the work going satisfactorily. Training and supervising of the field work was a full-time job for a twenty-five man camp or larger. The office work was a must as the progress and cost records had to be sent in daily. Each camp had a commissary which added to the office part of the job. Some of the camps did not have telephone connections to start with.

Some of the chief spotters were extra good; others had trouble in determining bug trees. Some had difficulty in making dependable maps. To start with, it seemed almost impossible to get a satisfactory job of spotting done. Bug trees were missed, old trees were tagged, trees were not located correctly on the maps. Sometimes it was difficult to get extra copies of the maps for the treating crews. Spotting was done in strips across the sections; some corners and lines were hard to find. Some land was not surveyed. When it was raining or snowing, it was impossible to do a good job of spotting. On stormy days, the spotting crews should have been put on treating work. It was necessary to have the spotting well ahead of the treating crews as the treating was done by drainages.

The spotting work needed good woodsmen who could travel through the brush and timber and be able to look around at the same time. It seemed impossible to hire enough men of this type. The treating required good axemen and sawyers who could fall the bug trees without hanging them up. Where the bug trees were scattered, it took a smokechaser type of man to find them easily and quickly. Where there were many men and boys around Coeur d'Alene who needed employment, many of them could not "cut the mustard." It seemed as if there were always cooks coming and going. Some quit, others were fired. Some of the treating was contracted to gyppos. This worked well with the best gyppos but was very unsatisfactory with the others. About the second week in June, the treating was nearing completion in most of the areas except the head of the river where there was still some snow.

Keeping the camps supplied with grub, mail and commissary was supposed to be a weekly pack string trip but often extra trips had to be made. The accounting for all the equipment was a big job. The regular district work was crowding in before the bug work was completed. The future bug jobs were not so large and not so high pressure. Their problems seemed to be about the normal run of district work.

The control of insect epidemics, tree diseases and fire are always expensive. Where preventive measures can be used, they are usually more practical than later control. The amount and value of timber lost through bug control treatment and the cost of the treatment was of considerable concern to me in 1930. The expense of growing timber to maturity, the taxes paid by private owners, the cost and work of fire protection; planting and other expenses justify the salvage of bug attacked trees under normal "bug" conditions. With the coming of more intensive forest management, it should be possible to harvest many bug attacked trees before the emergence of the new adults. Where this is practical, it will help prevent epidemics. Good forest management must solve the insect problems to keep ahead of the bugs.

C.C.C. Tree Planting 1934

Elers Koch and many others were interested in getting the C.C.C. enrollees working on tree planting as reforestation was one of the big objectives of the C.C.C. program. A good, fairly large area close to established C.C.C. camps was needed for a trial run. Up to this time, there had been no large C.C.C. tree planting projects in this region.

The Coeur d'Alene Forest had an area of about 1800 acres close to two camps that was picked for this project. This area was north of Brett Creek on the west side of the Coeur d'Alene River in Sections 7 and 18, T. 52 N., R. 3 E. and Section 12, T. 52 N., R.2 E., B.M. Part of this area had been burned over in 1919, the rest had been logged soon after. All of the area had burned over real hot in the large McPherson Fire of 1931. It was an ideal chance.

There was a C.C.C. blister rust camp at Nowhere Creek, F-155, and another, F-153, at Rock City. The blister rust work would be through for the season by the middle of September. Usually this would be a good time to start fall planting. These camps were being transferred to California for the winter. Most of the camps going to California were moving the last of September. Arrangements were made to hold these two camps until the last of October for this planting job and for road construction.

Elers Koch and Charles D. Simpson, Forest Supervisor, were especially interested in getting a good planting job done by the enrollees. Paul E. Nelson and I were assigned to this project to train the foremen and enrollees in good planning practices, to inspect the work, iron out the problems that would come up with the camp commanders and camp superintendents and "ramrod" the job through. It was planned to use ten fifteen-man crews, five from each camp. Everything was lined up to go as soon as it rained enough so that a satisfactory job could be done.

The first trees were gotten September 21st when about half an inch of rain fell. More rain was needed on most of the area but the weather stayed dry until October 17. Two crews were kept planting on the north slopes and moist sites. The crews were changed so that all foremen and enrollees who were to work on planting would have training and experience when more rain came. Many of the best enrollees went home the last of September when their time was up. Many of the replacements did not have woods experience and were not accustomed to hiking.

As time went by and it stayed dry, everybody became concerned about not being able to plant as planned. On October 16th, Elers Koch and C.C. Strong came over to size up the situation. It was decided to try to plant all the trees that had been lifted at the nursery, if possible. This was a big order as the camp commanders were getting ready to move. By this time, they had lost any interest that they may have had in the planting project. They were opposed to the boys working in bad weather as they did not want to take any sick boys to California!

It rained and snowed October 17 and 18. Planting was done on the 19, 20, and 22. However, we were able to get only three crews from each camp. More rain and snow came on the 23, 24, and 25. The camp commanders and others were putting the pressure on to call the planting off Simpson and I wanted to "hang tough" until the end. October 26 the weather cleared. Nelson and I were at F-155 but the camp commander, doctor and superintendent had decided the planting was over. They refused to let us have any crews. I went to F-153 and talked the situation over with the camp commander and the superintendent. They agreed to let us have as many men as they could for the next four days. With the getting of four crews from F-153, we finally put enough pressure on the commander of F-155 to get three crews from this camp. All the trees which were lifted for this project were planted by the evening of October 29. If the rains had come in September, I am sure that all this area would have been planted as planned.

The following paragraph is a summary of accomplishments on this job:

276,300 of 2-2 white pine were planted on 406 acres, 680 per acre, spaced 8' x 8'. 74,000 of 2-0 ponderosa pine were planted on 109 acres, 680 per acre, spaced 8' x 8'. White pine costs: trees $5.56, planting $6.36, other $1.28, total per acre $13.20. Ponderosa pine costs: trees $1.46, planting $6.35, other $1.25, total per acre $9.06. The wages per man day for the enrollees was estimated at $2.00. The effective planting time per day was about 5-1/2 hours. The average number of trees planted per man day 385.

For the amount of planting accomplished, this 515 acres probably represents more "pressure" than any plantation in this region. While this project did not measure up to expectations, it showed that with training and supervision most of the C.C.C. enrollees were capable of doing satisfactory planting.

K.D. Swan, the regional photographer, took a number of pictures of the different enrollee crews planting trees on this area. Some of these pictures were used in C.C.C. pamphlets and bulletins. Most of the enrollees liked the tree-planting work.

|

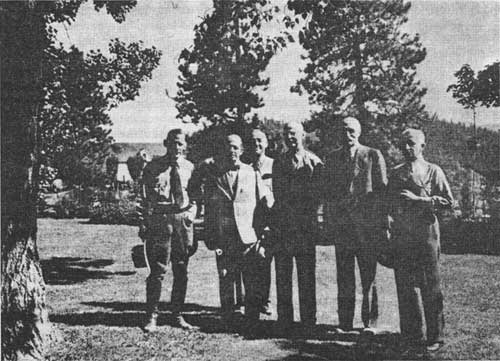

| A visit to the Remount Depot — 1937. Left to right: Elers Koch, Henry S. Graves, Meyer H. Wolff, H.A. Smith, Gifford Pinchot, Evan W. Kelley. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/early_days/3/sec14.htm Last Updated: 15-Oct-2010 |