|

Early Days in the Forest Service Volume 3 |

|

FORDS COME INTO THE NATIONAL FORESTS

By David S. Olson

(Retired 1944)

Recently I stayed overnight at Savenac Nursery. For a long time I lay awake listening to the constant hum of cars and trucks on nearby Highway 10. I thought of all the cars I had seen parked at the bunkhouse and the quick exodus of the men immediately after supper to see a movie in Wallace, only a 45-minute drive. I recalled the cars I had seen recently at lookout stations and remote blister rust camps, and the fleet of trucks and cars at each Ranger Station. Then I turned time back forty-some years when I was stationed at this spot. For a few moments my mind dwelt upon the quiet nights, the serenity of simple living, streams full of trout and a stimulating job unfettered by the complexities and frustrations in a big organization. But soon this nostalgia was crowded aside as humorous incidents associated with the coming of the auto tumbled into my memory.

I got my first car, a used Model T roadster in 1916. The Mullan Trail (later to become Highway 10) was barely passable from Savenac to Missoula. From Savenac west was no-man's land as far as car travel was concerned. To make the 90-mile trip to Missoula I would first spend a day overhauling the car - new clutch bands, brake bands, valve grinding, etc. Loaded with three or four extra casings, an extra spring and commutator, repair kits and every conceivable tool - oh, yes, and carbide for the lamps - I'd start out at daybreak and if lucky, make Missoula by midnight.

The first car purchased by the Forest Service for Region One was a Model T touring car for the Ranger of the Ekalaka division of the Custer. This was about 1917. Shortly thereafter Savenac Nursery purchased a Model T, one-ton truck. This was of the vintage with the solid rubber tires on the rear wheel. It took me two days to drive the new truck from Missoula to Savenac. The most difficult section of the road was a place called Nigger Hills, near Alberton. This stretch was a series of short, steep, roller-coaster-like pitches strewn with boulders and rock outcroppings that defied modern transportation. It must have been here that the 24 boxes of Macintosh apples in the truck changed from solids to liquid.

About this time the Mullan Trail was opened to Wallace. This was accomplished by some county patch work and, at least in one case, by contributed help of local people. The final stretch blocking through passage to Wallace was made a public event. With picks, shovels and wheelbarrows (and free beer furnished by local saloonkeepers), residents of Saltese and Taft scratched several miles of road across the hillsides to forge the final link for car travel from Missoula to Wallace.

To publicize the opening of the road now designated the Yellowstone Trail, a Missoula man named Beck raced against time from Missoula to Wallace. Preceding the day of this event, notices were sent out to the inhabitants along the route to fill chuck holes, remove serious obstructions and keep their livestock off the road. We cheered as Beck went thundering by the nursery in a cloud of dust at 30 miles an hour.

Painted yellow bands on poles and fence posts were the first highway markers for the Yellowstone Trail. They served only to locate the route like tree blazes in the woods. It wasn't long before the first roadside advertisement appeared. This was in the form of a directional sign shaped like a hand with the index finger pointing the way of the route. These signs contained mileage information to the next town and warnings, such as "sharp curve," "railroad crossing" and "steep grade." I recall one of these signs that I liked. It read "Step on the gas for the next half mile." The only hint of advertising on these signs was the name "Dolbys." No one knew who or what "Dolby" was until he reached Spokane. There in the window of a men's clothing store was a large replica of the highway sign with the words, "Safe at Dolbys."

After the opening of the road, autos appeared in ever-increasing numbers. The route went through the nursery so we saw them all. In those days a large percentage of the tourists stopped to look over the nursery. There were, of course, no established campgrounds or motels and many were the requests to permit them to camp within our fenced enclosures. They were scared of wild animals. Many stopped to drink and fill their canteens with the tepid water from the surface sprinkling pipes. They were familiar with tap water but were hesitant to use clear, cool water from the streams along the route.

Ranger Frank Haun bought a new Model T about every two years. It was fascinating to watch him get into his car. Frank was a big man with an unusually large paunch. To get behind the steering wheel, he had to cinch up his belt. That made a deep groove for the rim of the steering wheel to travel in. He took great pride in each new car that he purchased and kept it clean and shiny until fire season. Then it really took a beating; axes, shovels and saws were tossed on the back seat and firefighters crammed the frail running boards. From then on deterioration was rapid. A Model T didn't last long on those roads - at about 4500 miles they were ready for a trade-in. Tires costing $30.00 apiece (3-1/2 x 30) would last no more than 3,000 miles. We bought four-inch-wide leather bands, studded with steel discs, to slip over the casing as a means of prolonging their life, but the sidewalls continued to blow out. There were no garages or auto mechanics to help in our troubles. The spark coils seemed to give the most trouble. It became pretty exasperating cranking the car when things were not working right. I recall coming home one evening and seeing our local station agent's car stalled in the middle of the road. He was off to one side throwing rocks at it.

A Ford was responsible for a mystery on the St. Joe Forest that puzzled the Forest Service for several years. A messy log deck was developing along the old Emida road and no one seemed to know who was doing the logging. When the case was broken, the local Ranger was found to be the culprit. Ranger Bill Dawes, of the Palouse District, was one of the early recipients of an official car. He often traveled the Princeton-to-St. Maries road where he had to negotiate the steep Emida Hill. The brakes on his Ford would not hold going down this hill so before making the descent he would stop and fell a tree, cut out a section, and chain it to the rear of his car. Dragging this down the hill relieved his brakes. At the bottom of the hill he unhooked the log and rolled it to one side.

We gave a lot of our time helping the early tourists. It seemed to be expected of us at Savenac since we represented the Government. I usually allowed an extra two hours on my travel schedule going east over Camel's Hump, or west over Ford Hill, to help clear the stalled traffic. These were big hurdles for a Model T. The Fords overheated on the long pulls and unless the gas tank was near full a Ford would stall on steep pitches because the gas feed to the carburetor depended upon gravity flow. When one car stalled it usually held up a line of cars from both directions because there were few turnouts on the mountainous roads in those days. Sometimes those traffic jams were pretty difficult to untangle.

The so-called tourists of this early period were largely local travelers and people on the move to new locations. Many were farmers driven from eastern Montana and North Dakota by the severe 1917 drought. With the improvement of road conditions and the sprouting of gas stations and garages in the small towns along the way, came the sight-seeing tourists. My first realization of this change came one day when I was walking along the road toward the nursery. A large black sedan drew up from behind and stopped. A liveried chauffeur asked if I wanted a ride. I thanked him and said I'd stand on the running board since I had only a short way to go. Looking into the car, I saw two elderly ladies sitting in rocking chairs. They smiled and one of them said they were seeing the wild West for the first time.

Uncle Sam's Biggest Nursery

On a honeymoon trip by horseback, Elers Koch spotted a small clearing abandoned by a German homesteader named Savennac* that impressed him as an ideal site for a small tree nursery to serve the needs of his forest. That was the beginning of Savenac Nursery.

*This spelling may be incorrect but it was not Savenac, as the name of the nursery is spelled.

Seed beds were prepared on this small patch in 1908. Three similar nurseries were under development in the Region at this time; Trapper Creek to serve the Bitterroot; Camp Crook, South Dakota, to serve the Dakota National Forest; and the Boulder Nursery for the Helena. These small nurseries were operated by District Rangers and called Ranger nurseries. The disastrous fires of 1910 changed all this. Now a tremendous job of reforesting the 1910 burns faced the Region. Savenac Nursery was wiped out by these fires before the first crop of seedlings was ready for planting but it was decided to rebuild and enlarge this nursery to serve all the western forests of the Region and particularly the planting needs on the three million acres burned over in 1910. The Boulder Nursery continued operations until 1916; the other two nurseries were abandoned earlier.

Land clearing of the 31 acres of benchland along Savenac Creek started immediately. By 1915 it was fully stocked with about 10 million trees of various age classes and ready to maintain an annual output of three million trees. It had become the largest tree nursery in the Forest Service.

During this early period of development, Savenac Nursery remained under the administration of the Lolo Forest. Supervisor Koch spent much of his time directing the work, with Ranger Frank Haun and Assistant Ranger Will Simons supervising operations. Research to aid in developing nursery practices was being carried on at the Priest River Experiment Station. H.H. Farquhar was chief of planting.

Since the nursery was now serving many forests of the Region and the work there was looked upon as highly specialized, it was decided in late 1914 to place it under the direct supervision of the Regional Office. In the spring of 1915 it assumed this new status and I was offered the job as nurseryman, at a salary of $1,100 per annum. At the same time E.C. Rogers was transferred from the Priest River Experiment Station to Savenac to continue research on the propagation of planting stock for this region. Rogers wanted to carry his nursery studies into the field for final determination of results and for this purpose established what we called the Wallace Experimental Area, about three miles south of Wallace on Placer Creek. Today this is an interesting study area.

If ever a guy was plopped squarely in the middle of things to work his way out, that was me when I landed at Savenac March 1, 1915, fresh out of school. I think the biggest break I got that difficult first year was an unseasonably early spring. We were able to put the plow in the ground the day I arrived and there were no setbacks due to unfavorable weather that year.

Of course, there was no clerk at the nursery and I was completely ignorant of fiscal and administrative procedures so I soon encountered trouble. In those days we hired and fired at will. Most of the 40-man crew consisted of transients "riding the rails" and dropping off at Haugan for a short period of work at the nursery. When they quit or were fired, I paid them with personal checks and obtained "cash receipts" for the payments. These receipts were then submitted on expense accounts for reimbursement. Thus, it seemed, my slim capital would serve as a revolving fund and take care of the situation ad infinitum. That is, I thought I could send in my expense account and have the expense check back in a day or two for deposit. Hah! I didn't know how many errors the fiscal office could find in an expense account. As a result, the three saloonkeepers in Haugan were soon waving fists full of checks in my face - checks that had been returned for lack of sufficient funds. I knew nothing of the $50.00 limit on purchases without bids until the fiscal agent began firing back the vouchers. Nor did I know that laborers for the Federal Government could not be paid on a piece-rate basis such as we were using on some of the nursery operations for speeding up performance. I was told to adjust the men's earnings to an hourly basis on the payrolls and this resulted in some fantastic rates, such as 28-39/61 cents an hour. Incidentally, the base rate of pay for labor was 25 cents an hour plus board, which cost the Government about 25 cents per meal.

The total planting allotment for Region One was about $40,000 at this time. This was enough to pay all the costs related to producing the stock and planting about 4,000 acres annually. At Savenac, every effort was concentrated in producing as much good stock as possible on the 31 acres at the lowest possible cost. Development work went into research, devising new methods and equipment, and time studies to improve efficiency in nursery operations. Buildings and grounds lacked much to be desired and our standard equipment and watering systems were "haywire." We got along somehow.

In a few years the work at this hustling young nursery was getting some attention from the outside. Research was paying dividends in reduced losses and high-quality stock. Cost of tree production was the lowest in the Service. Some of the new developments in methods and equipment were aimed at meeting problems peculiar to the Region but found wider application and were adopted elsewhere. For example, the cylindrical burlap-covered tree bale was developed for pack mule transportation. In those days, nearly all tree shipments left Savenac by railroad express. From the nearest railroad point the trees were taken by pack train to the planting camps. The dead weight of the wooden crates formerly used was about equal to the weight of the trees. Material used for the bales was much cheaper and its weight only a few pounds, and this cut transportation costs just about in half. The bale is in general use today even though transportation of trees from the nurseries to the planting sites is largely by truck.

Another change made in these early days that was receiving wide acceptance was the use of shingle tow (the shreddy sawdust from shingle mills) instead of sphagnum moss for packing material to keep the roots of the seedlings moist en transit. Shingle tow was available at a local mill for the cost of hauling, whereas sphagnum moss cost $20.00 per ton plus freight from Wisconsin. In addition, the moss had to be fumigated when it reached Savenac to avoid the danger of introducing the eastern larch saw fly to this region. The bales of moss were placed in a tent and subjected to potassium cyanide fumes for 24 hours. A guard was stationed outside the tent during this period so no one would accidentally stick his head in the "gas chamber." Today, nurseries all over the country use shingle tow in preference to sphagnum moss when they can obtain it at competitive costs.

We were beginning to have visitors. Foresters from here and abroad were calling at the nursery to see our operations and tourists were stopping in increasing numbers. E. E. Carter, Chief of Timber. Management in the Washington Office, was showing unusual interest in developments at Savenac and talking about them to other Regions. Savenac Nursery was beginning to ride the crest.

E. F. White, who had succeeded Farquhar as Chief of Planting about the time I took over the nursery, now saw a chance to go after the other phase of developments for Savenac - improvements in buildings, grounds, and other major facilities for operating the nursery. He brought Regional Forester Silcox out to the nursery and convinced him that Savenac should be made a showplace for the Region. Silcox was enthusiastic and immediately sent an engineer to the nursery to develop a 20-year improvement plan including detailed design and specifications. The plan provided facilities for regional meetings - especially during the winter - as well as improvements for the operation of the nursery. We had no idea where the money would come from for these improvements but it developed that by having the plan, money came from an unexpected source. Carter, in Washington, saw to it that unexpended planting balances in other Regions were transferred to Savenac. These balances were never available until about June 1, so for three years there were hectic times during June to make the most of these windfalls. The original 20-year plan was completed in three years. Today that would be simple with the many servicing divisions in the Region, but we had to do our own purchasing and our own construction work. For example, I had never laid a brick but I learned and by the time I left the Region I had built 16 chimneys and a stone fireplace for the Forest Service. Our greatest obstacle at this time was the $650.00 statutory limitation placed on all Forest Service buildings. There was no limit to water systems, septic tanks and the like, but building costs were thus limited, including the cost of labor.

In 1920 I was promoted to chief of planting. Instead of moving to Missoula, I transferred the planting office to Savenac. Savenac was now a little community of residences and yearlong inhabitants. The building limitation had been increased to about $2,000.00 per structure, so we were able to erect several nice cottages for the increased personnel. G. Willard Jones succeeded me as nurseryman, W.G. Wahlenberg handled research (after the death of C.E. Rogers), C.E. Knutson did the planting survey work, and we had a clerk. Frank Haun remained as Ranger for the Savenac District until his retirement 20 years later.

When Koch was placed in charge of Timber Management, he insisted I move the planting office back to Missoula. I did this, reluctantly, in 1927. Wahlenberg left about this time to work at the Eddy Tree Breeding Institute, now the Forest Genetics Laboratory at Susanville. Up to this time planting and nursery research had been financed and directed by the planting office. That work was now turned over to the Experiment Station in Missoula. With a big boom in planting work getting under way in the new Region 9, Jones was transferred there to develop the large Rhinelander Nursery in 1931. Bill Apgar replaced him at Savenac and remained there until 1933 when he transferred to radio development work in the Regional Office. Knutson also transferred to Region 9 in 1931 as Ranger on the Huron Forest. Jess Fox followed Apgar at Savenac. I left the Region for the Shelterbelt Project in 1934. Of all the men I have named in this sketch of Savenac Nursery only Apgar, Wahlenberg and I are alive today.

There is another chapter to Savenac's history - from the CCC days to the present. That is for someone else to write. I wasn't there.

Summer Work

To forestry students at the University of Nebraska it was especially important that they acquire woods experience during their summer vacations. Usually we went West, although I did spend my first summer mapping and cruising in virgin hardwood forests in southeastern Kentucky for a privately owned company.

I came to District (Region) One, first in 1913 with three other students to work as summer guard for Ranger Elmer Findell on the Seeley Lake District. After getting instructions from Supervisor Rutledge Parker in Missoula, we boarded a train for Drummond. From there we went by stage (wagon) to Seeley Lake via Helmville and Ovando. The trip required two full days of travel; today it can be made in less than two hours.

We covered most of the District that summer, on boundary surveys, trail work and telephone line construction. I learned to use the axe, saw, canthook, and climbers, and to throw the diamond hitch. I had trouble with the canthook at first. A lumberjack in our crew suggested perhaps a chew of his "snoose" would help. I fell for the suggestion and in a moment became dizzy. I took the canthook and got a good bite on a log, wrapped my arms around the handle and let the rest of the world whiz by.

This was wild and beautiful country in 1913. There were few human inhabitants; no summer homes. There were no fires that summer so we were free Sundays to fish the lakes and we fished them all.

On the way out, we hiked to Bonner and rode the electric interurban to Missoula. Hearing that men were wanted at Savenac Nursery, we hopped a train and put in two weeks' work before going back to school. At Savenac I met Elers Koch, Roy Phillips and Frank Haun, men who a few years later were to become my close associates.

Western Montana had gotten in my blood, so I was back for the summer of 1914, working as guard for Roy Phillips, Ranger of the Superior District. Wages were $50.00 a month and from this I furnished my own grub. Mainly, I was lookout on Illinois Peak that summer but, in addition, I gathered a lot of odd assignments. One morning Phillips said, "Dave, we'll either have to build a new barn or dig out the manure." So I lowered the floor about two feet. I also dug half a mile of ditch for the water pipe to the Ranger Station.

The lookout tower on Illinois Peak was a rickety affair with an open platform on top. The map and alidade were covered with a sheet of canvas when not in use. The telephone was at the cabin, half a mile away. Neither tower nor cabin had lightning protection, and the cabin had a corrugated iron roof. Cranking the phone or picking up the receiver to talk to the Ranger during an electrical storm was about as hazardous as reaching for a rattlesnake in a gunny sack. During the early part of the fire season, I made observations from the lookout at regular periods. Between observations I built a mile of trail and a foot bridge, sharpened fire tools and cooked. My cabin was at the main crossing into the St. Joe and Clearwater countries. Packers supplying camps, particularly the large U.S.G.S. survey camps, used my station as an overnight stop. I was the cook. In those days the only things we got in cans were tomatoes and condensed milk. The rest of the food was dry - dried fruit, powdered eggs, beans, rice, bacon, etc. Since I had to furnish my own grub, the packers repaid me by dropping off a slab of bacon, a sack of flour or some other item of food. I finished the summer with twice as much food as my original purchase. I "sold" this to an acquaintance in Superior, but he never paid me.

Occasionally Phillips would release me on Saturday afternoons to come down to the dance at Superior. I'd hike 26 miles to town, dance all night and hike back to the lookout Sunday morning. Today I wouldn't cross the street for a dance.

In late summer visibility became poor from many fires and I was instructed to patrol the ridge on horseback 10 miles east one day and 10 miles west of the lookout the next. Later, as the haze became denser, I prowled around in the upper drainages seeking suspected smokes, sometimes sleeping out, with my horse tied to a near-by tree. One afternoon while patrolling the ridge I was knocked out by lightning. I was riding serenely along and the next thing I knew I was struggling to get up, the air was acrid with fumes, the horse stood near by. This experience left one profound thought - you'll never know when lightning hits you.

Later I was called from my lookout duties to fight fire. We had a bad one on Dry Creek that kept us busy for a week. At the close of the fire season, I was sent back to my lookout cabin to meet a bunch of firefighters coming out of the Clearwater. When I arrived at the cabin there was three feet of snow and it was snowing so hard one could see but a short distance. I made gallons of mulligan, soup and coffee. Every half hour I would go outside and fire several shots. About three in the afternoon the firefighters began to arrive and a sorry looking bunch they were, mostly "boxcar bums," shod in wornout oxfords, clad in thin civilian suits. When they reached the snow they had lost the trail and were scattered all over the mountainside. We hollered and fired more shots to direct them to the cabin. Finally all but one were accounted for. I went out in search and found him lying in the snow. He had reached that point of numbness where he only wanted to be left to sleep. After much prodding, I got him up and carried him piggyback to the cabin.

After the men were fed and partially dried out - and had smoked all my cigarettes - I helped them wrap strips of burlap around their feet and legs. Then evergreen boughs were tied to their feet to serve as snowshoes, and they were sent on their way down the ridge to bare ground and civilization.

My last assignment on the District that summer was to take a mineral examiner from Missoula into the back country to inspect some mining claims. We went in with our two saddle horses and a pack mule to carry camp equipment and supplies. The last night out our saddle horses left camp and went down the trail. Luckily, we still had the mule which had been hobled. The mineral examiner said he would go down the trail and finish his work while I packed the mule. That was some job. Now I had two saddles and a pair of bridles to add to the already overloaded mule. But worst of all the tent was frozen. Rain had fallen during the night and frozen toward morning. Folding that tent was like bending sheet iron. When I finally got the mule packed all that showed of it was the face and four feet. Thus we started down the trail. When I reached the mining claim there was a note on a tree stating the mineral examiner had finished and gone on ahead. At a meadow farther down the trail was another note stating he had caught up with the horses and gone ahead to catch a train for Missoula. Since he failed to tie up the horses they had moved on and I found them 20 miles later quietly cropping grass at the Ranger Station.

Again I went to Savenac Nursery to work several weeks before returning to school. This time Jim Brooks and I were used on time studies being made of the transplanting operation. Some members* of the Regional Office had become interested in the principles of scientific management as practiced in the Franklin auto factories at that time. Savenac Nursery seemed to be a good place to apply these principles. As a result of the time studies that fall Savenac developed a transplanting operation that was by far the cheapest in the United States. In a two-hour period, Jim Brooks and I, as a team, transplanted 9,000 seedlings, a record that still stands. It probably was my interest in these studies that was instrumental in my being offered the job as nurseryman the following year.

*Regional Forester F.A. Silcox, Assistant Regional Foresters Dave Mason and Roy Headley and Chief of Planting H.H. Farquhar.

Stopping off at Missoula enroute to school, I learned that a Ranger's examination was to be given the following day so I decided to take it "just for the heck of it." Elers Koch gave the examination. Fourteen took it, among them Jim Bosworth and Tom Crossley. I don't remember what subjects were covered in the written portion of the exam but I do recall some of the field tests. After identifying some range plants and scaling logs, we went out to Koch's home on Beckwith Avenue. From his barn north to the river was prairie. First we took turn; to run traverse with compass, around a staked area, and pace the distance. Then each took his turn at packing a horse. The final test was to saddle a horse and ride as hard as it would go across the prairie toward town. A cockle burr was placed under the saddle blanket to liven things up a bit.

Tales from the Past

Joe Halm was leading a string of pack horses up the North Fork of the Coeur d'Alene River. It was one of those matchless Indian summer days. The warm afternoon sun tempered the crisp air just enough to remove the autumn chill. Frequently, Joe turned in the saddle to observe with deep contentment the silent forest of tall white pines, the yellow and gold of aspen and larch foliage splashed on the green timbered slopes, the clear stream along the trail. Again his glance rested on the pack horses trailing behind. Joe counted one, too, three, four, five, six. Now he recalled the Ranger's admonition that morning as he led the horses out of the corral, "Take good care of my horses, Joe, and be sure to bring all seven of them back." Again Joe counted the horses; there were only six. He must have lost one. Perhaps the laggard would catch up with the rest of the string, so for a while Joe waited. Then he grew impatient. He turned the pack string around and started back. As he retraced mile after mile, with no sign of the missing horse, hope dwindled.

By midnight he had returned to the Ranger Station. The commotion of getting the horses back in the corral had aroused the Ranger who came out with a lantern, and much cussing, "What the blankety-blank goes on out here? Joe, what in the world! I figured you were camped for the night at least 20 miles up the trail." Joe looked down from his saddle and wearily said, "I lost one of your horses. Did it show up here?" The Ranger counted the horses and shook his head, "They are all here all seven of them." Joe pointed to the pack horses, "Nope, only six." The Ranger turned in disgust and sauntered toward the cabin shaking his head. At the door he turned and called back, "Joe, how about counting the one you're sitting on?"

(Maybe it wasn't Joe, but that's the way I heard it. - D.S.O.)

It was midwinter and I was bound for the Falls Ranger Station. There had been a heavy snowfall during the night so I had difficulty getting someone at Priest River to take me up to the station. Finally a garage man consented to try it with his new snowmobile. This was a Studebaker touring car with sled runners made of 2 x 12-inch planking substituted for the front wheels. The rear wheels were well wrapped with logging chain. We made fair progress as long as the steering sled could be kept in the ruts of the partially broken road, but once the heavy runners sliced into deep snow it was impossible to steer the darn thing. Then we had to back out like a switch engine to the main line. About four miles out of town we got hopelessly stuck and broke down trying to get out.

I changed to my field clothes in the snow and started walking. Later, a rancher in his sleigh drew up to me and offered a lift. We chatted, and among other things the rancher asked if I knew Dr. Wier — forest pathologist for Region One at that time. I said that I did and planned to see him in a few days.

"Well," the rancher said, "Dr. Wier had his camp on my ranch last summer and I used to watch him collect those orange toadstools growing on tree trunks and put them in jars of alcohol. It was none of my business, so I didn't ask any questions. When you see Doc, tell him I've tried about everything but that's the damndest hooch I ever tasted."

*****

Today there is little left to identify this last stop on Highway 10 and the Northern Pacific branch line going west before reaching the summit at Lookout Pass. But at one time it represented quite a community. It was the site of the construction camp for the Milwaukee Railroad when in 1908 and 1909 that road was boring its way through the Bitterroots under the Montana-Idaho divide. Many stories have come from this construction camp. This one deals with the origin of its name - Taft.

Our president at the time, William Howard Taft, was on a western tour. Going up the St. Regis valley bound for Wallace he was reminded of the new transcontinental line being constructed by the Milwaukee Railroad and the rip-roaring construction camp ahead. The President asked to have his special train stopped at the camp. As the train slowed to a halt, workers, barkeepers, and girls poured from shacks and tents to learn about the special train. From the observation platform, President Taft motioned for all to gather around him. Then he scolded them. He told them their lawlessness had made this place notorious over the breadth of the land. It was a disgrace to the country, a dirty smudge on these fair United States. He demanded they do something about it. They did. As the train departed they gave three rousing cheers, and named the place in his honor.

*****

In 1908 the U.S, Forest Service was just getting organized. There were few men in the field to manage the millions of acres set aside as National Forests in the rugged West of those days. The problems encountered were, to say the least, different, and sometimes as difficult for the bosses near the Great White Father in Washington to solve, as for the young upstarts who encountered them.

A young forester newly assigned to a vast wilderness through which a transcontinental railroad was being constructed learned that some women had moved in close to a large construction camp and were occupying National Forest land. He asked them to vacate. They told him to "go to hell." Then he wired his chief "Undesirable prostitutes occupying Federal land. Please advise." He received this reply: "Get desirable ones."

|

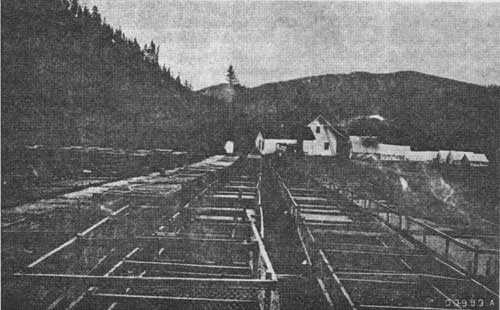

| Early day view of Savenac Nursery and new seed beds. |

|

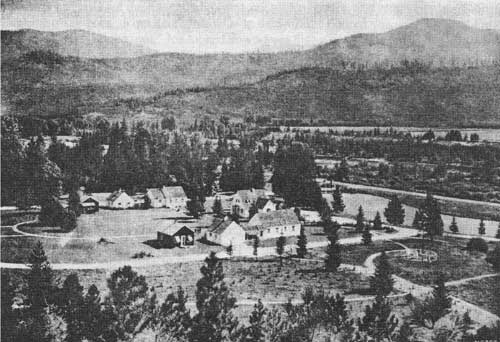

| Savenac Nursery, 1941. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/early_days/3/sec18.htm Last Updated: 15-Oct-2010 |