|

Early Days in the Forest Service Volume 3 |

|

By L.M. (Locke) Stewart

(Division of Fire Control)

The 1919 fire season was a rough one. It could have been even worse but for the virtual barriers still in many areas where 1910 burned clean. A volume could be filled with the feats of Phillips, Urquhart and many like them in their stubborn efforts to be everywhere and to do everything needed. Roy and Crete had Ranger Districts adjoining along the Idaho-Montana State line where I rode daily patrol after the smoke blanket became so thick that observation from Illinois Peak was useless. From nearby I watched one fire crown across the line into Montana in less than 60 minutes after it broke away near the mouth of Long Creek, six miles in Idaho. In its run two bands of sheep were caught and destroyed, almost 4,000 head. The herders and their horses and dogs outran the fire. Then came the long wait, two to four days to get weary, foot-sore men on the line - and the endless streamers of dust as the horse and his long-eared, intelligent working partner pounded the trails moving in supplies.

A few days later, with smoke thicker than ever, a fresh column appeared to be rising from a spruce basin in the head of Trout Creek, only two miles and in direct visibility from my route under normal conditions. Checking before going to a telephone to report, I found that a lightning fire had burned about ten acres in heavy fuels. It obviously had been burning in the spruce bottom for several days, spreading slowly, probably started by the same storm that had set the Long Creek fire. This was a costly fire discovery for me - I lost a fine horse. When a galeforce gust threw the top of a big spruce snag at us, I deserted him for the shelter of a windfall.

That fall, until snow drove us out, I doubled as packer and cook (?) for a crew appraising the loss in the huge Cold Creek fire near St. Regis. This fire had been started by the Milwaukee Railroad. Later the solicitors suggested that the proposed damage suit would be confusing - the U.S. had taken over railroads during World War I and was still operating them when the fire started.

The three Stewart boys had a distinct backwoods flavor, the result of growing up on a Western Montana homestead without benefit of feminine influence. We tended to duck for cover when strangers were sighted and if they proved to be female, were likely not to show at all. Our housekeeping was purely functional and cooking likewise, but we were at home in the mountains, no strangers to labor and better than green hands with stock, guns, traps and hand tools. So it followed that the local Ranger, Roy Phillips, would hire us as youngsters during the manpower shortage of World War I. In early June 1918, Roy took me on as a Forest Guard, age 15. I failed to survive a reduction at the beginning of the new fiscal year and hired on for the balance of the summer to tend camp (pack) and occasionally herd for a Washington sheep outfit trailing to summer range in the head of the North Fork of the Clearwater in Idaho.

I hired out to Roy again the following spring, $80 per month with my horse. Wages were high in 1919 - firefighters made 55¢ per hour. I think that if my account has any significance it must derive from what may be record tenure of direct and primary concern with Region One's fire protection job. Thus I will dwell thereon; few of us can resist an invitation to reminisce. If the prospect is boring this is the spot from which to skip:

The scars of 1910 were still quite fresh; dead trees mostly still standing and deep ashes still in place in many of the quiet basins along the Montana-Idaho divide. The lush growth of weeds and low browse in years following the big fire led to an annual invasion of out-of-state sheep taking advantage of mountain range unmatched for topping lambs. In 1919 the Lolo alone wrote permits for 48,000 sheep; thereafter falling snags and heavy brush gradually reduced the volume and availability of suitable feed. Big game, excepting bear, were relatively scarce in most areas, whether sheeped or not. Elk were almost nonexistent along the Clark Fork except for the recent plants on Petty Creek and near Keystone, west of Superior.

Forest officers were adept at getting good returns for the few dollars they had to work with. They were generally first-class firefighters but incurable optimists about fire; perhaps they had to be to persist against the odds facing them. There was much experimenting with tool modifications - or combinations such as a detachable shovel handle, the opposite end of which fitted the eye of a grubhoe and a number of versions of the axe-hoe which finally shook down to the tool given Pulaski's name. One such tool went together with a key and matching slot. It was less offensive to an axeman than the pulaski but required too much care.

Most of the men available locally for fire crews were skilled with hand tools and had a good appetite for labor. Individual production was relatively high, even by the IWW. The IWW were gaining a bad name in the convulsions accompanying progress toward improved employment and living conditions in the woods and mill camps, long overdue. There were few fixed detectors, none with living quarters on the point; most of the sketchy detection effort was in patrols by horse and hand-powered railway speeder. There were many "fire caches" of hand tools and standard lists to guide procurement of food supplies or camp equipment but no preassembled units of either.

There were frequent instances of initial attack action which would make creditable statistics today. For example, Phillips and his Maxwell picked five of us up one July evening in 1917. We bounced some 20 miles and hiked 6 miles in the dark by the dubious light of Roy's palouser to hit a lightning fire. It had spread to about 5 acres by the time we reached it, hot line on all sides. By daylight the fire was well under control, the full perimeter trenched and cool, by virtue of a mixture of tactics: direct attack where appropriate, parallel construction where the fire was backing downwind or downslope and indirect line held by burning out the more difficult sections. But it was a different story when fires escaped the men quickly available or, due to inaccessibility or inadequate organization, were already of project size when reached. Then there was often a woeful lag before crew action, accompanied by an understandable tendency, engendered by penny-pinching and staggering logistic problems, to settle down to extended defensive campaigns. Neither the public nor the Service was ready to spend the dollars required for positive action. To gain time for line construction and burning out with small crews, the fire boss often resorted to extensive use of indirect lines far removed from the fire front - an impressive tactic when successful but disastrous when saddled with poor luck or wrong judgment.

In Region (then District) One, as recalled, 1920 was an amiable sort of season when good fire records could be made without undue effort. There was high incidence of lightning fires but only average burning conditions and the organization was generally alert and potent after the 1919 shakedown. Phillips, now Assistant Supervisor, had organized the "Lolo Emergency Crew," an early, if not the first "Hot Shot" fire crew. In the spring we planted trees, piled slash, built trail and constructed a fireline around several sections of the Big Creek sale cutting area. This was scheduled as a prescribed burn but was never burned, to my knowledge. Fire season came and we were on call to serve as a unit or as individual smokechasers or overhead where needed. We actually were used quite freely. The initial travel from our base at Haugan was usually on the N.P. or Milwaukee tracks - by train, special engine, or railroad "speeder." We sometimes went the hard way. I remember that three of us hiked overnight from the St. Regis River over Wards Peak and some eight miles onto the St. Joe to reach a fire which that forest could not readily man.

It is interesting to note that at this time the region was trying out a modified zone organization. The Missoula (broken up in 1930), Bitternot and Lolo Forests made up the "Missoula Unit." A.M. Baum was Lolo Supervisor.

In the early twenties I put in 4 seasons for Ed Mackay as "clerk," "bull smokechaser" and packer. In the wintertime I usually hit the logging camps, including 2 winters packing 11-head mule strings, moving supplies into the white pine flume camps which were then flourishing in the St. Joe River country.

Ed was Ranger of the combined Powell and Lolo Districts, and Bill Bell of Elk Summit. Between them they had 5 and 6 regular strings. End of road was at the Mud Creek station, above Lolo Hot Springs and headquarters of the Lolo Ranger District. This was the heyday of the pack mule he even dominated the improvement program with large (10 to 15-man) trail crews blasting out high-standard trails on excellent location but getting low mileage. Dynamite came to Mud Creek by Model T truck and you hauled it to Powell by the stringload, usually with the blasting caps rolled in a slicker behind your riding saddle - shades of Seth Jackson!! The style of packsaddle still standard had evolved and had been named after Decker Brothers, who had strings on the Joe. They no doubt contributed to its development.

The skilled trail men were fine firefighters. Lookouts were widely scattered, 3 on the big Powell District. L-6 (cupola) type lookout structures were being placed and the lookout man moved up on top of the hill under a lightning-protection cage of 6-gauge iron wire. In 1922 we strung No. 9 iron telephone wire down the Lochsa and up Jerry Johnson Ridge to Indian Post Office. The post office had previously communicated by heliograph via Beaver Ridge, if at all.

Group training of summer guards began to be standard practice. The Stonebridge folding lantern was replacing the palouser which had a bad habit of dropping its candle at the wrong time. Along came R- 1 smokechaser rations - the first ones had dehydrated spuds and carrots which required hours of soaking to soften to cookability, and also fat bacon which was itself inedible but provided grease for frying fool hen or rabbit. The Kimmel campstove had been around for several years but now teamed up in fine preassambled outfits with mess gear, tools, camp equipment and bed rolls. The latter consisted of three thinnesses of OD blanket rolled inside a WWI shelterhalf and were soon to be discarded in favor of the kapok roll. Happy day!

1925 through 1928 were not generally bad fire years in the Region but provided high spots; 1925 and '26 were both quite rough on some forests, and particularly the Kaniksu which really took a beating. These two years were characterized by exceptionally violent lightning storms in northern Idaho and western Montana. Construction of fire protection roads and trails was stepped up considerably. Interest in use of aircraft was growing steadily, with Howard Flint very active. Early in 1927 I had been given a C.S. appointment, one of the last from the old Ranger examination which had deteriorated since the shoot, chop, pack and ride days.

1929 was a tough, violent season over much of the Region and would not stay down - we were digging fire from under November snows. R- 1 was on the receiving end of fire details in those days and many officers from Regions 2 and 3 were glad to head for home that fall after weeks of steady firefighting - no overtime pay, not even compensatory time.

This was the year of the great Bald Mountain fire which tied up unprecedented numbers of men and pack animals in an all-out effort at wilderness firefighting on massive scale. Also the year of Major Kelley's coming to R-l and the slogan "leave a black line behind you," backed by sound reasoning but often ineptly applied. And, for at least one Ranger, the warning that the "first period control" objective was about to become standard for all fires in the Region. This warning came when, on returning to base camp after going around an 1800-acre fire, I had word to call the Major. "Ranger Stewart, how many men do you need to control that fire by 10:00 a.m. tomorrow?" Impracticable perhaps in that particular instance but a concept that has done much for fire control in the Region. A few years previously, fire inspectors had been concentrating on suspected "over-manning" - it now became proper to inquire deeply into "extra-period" fires.

Following 1929 we were straining to build the roads long and narrow; to make every construction dollar count toward improved accessibility. Coupled with the relief programs which followed the 1929 crash this urge to open up country pushed low-standard mule trails everywhere. We also mapped an unbelievable mileage, of "truck trails" taking wheeled transport where we had not dreamed of it 10 years before. The bulldozer, crude at first, helped greatly and later became an important fire tool. Hundreds of lookout structures went up, tied to Ranger Stations by thousands of miles of telephone wire. Horse-powered plow units, now forgotten, were highly effective on many fires. The CCC crews turned out to be fine fire help, surprising some of us.

About 1930 Howard Flint had initiated Region-wide systematic analysis of the fire load and planning of the required organization. It was largely a desk production, done personally by the District Rangers, and the district plans tended to reflect too patently the experience and effort of individual Rangers. But this "Adequate Fire Control Plan" was a big step, well charted, and gave impetus and rough pattern to the better-financed planning program which followed, led by Hornby. For the west side of the Region, presuppression plans were well formed by 1935. In 1937 following the big fires of 1936, planning emphasis, some money and some Rangers, including myself, went to the east side as staffmen to help strengthen fire planning and organization.

Activated when the 1929 fires red-lined the need, the Region One remount depot near Nine Mile had become an effective unit. By 1936 delivery of fire supplies by parachute and free-fall was developing fast. This method threatened to outmode the mule for quick delivery; now it has done just that - may the smoke never again become too thick. Also by 1936 we were coming to depend upon the airplane to scout fires and to ferry men between airfields. The Region had built a few landing strips in and near the primitive areas. They were, and still are, decidedly primitive too but these strips effected major changes in back-country logistics. Fire control and the related improvements still occupied the major part of our time and effort.

1926, '29, '31, '34. (ouch!), '36, '39. '40. Each different and each plenty rough. Rough and hot enough to temper and put a keen edge on the Region's fire team at its all-time high for depth of trained crewmen, skilled technicians and experienced, able leaders. It would be unrealistic to fail to recognize the tremendous firefighting capability existing here in 1940.

World War II manpower shortages undoubtedly accelerated the expansion of smokejumping with a new concept of mobile striking force. World War II probably also speeded conversion of the Region's strong fixed-detector system to a combination "air-ground" system which makes heavy use of airplanes to supplement a skeleton lookout coverage. Post-war timber access roads have marvelously improved accessibility.

History may repeat with seasons of sustained critical conditions resulting in heavy losses in R-1. We do not yet have the means to prevent dangerous starts nor halt the first run of those fires that "light a-running," eager to get moving. But the Region will give a good account if the continued reduction in average annual burn does not drag organization too low, and especially if July will continue to bring those good rains which we denounce every Fourth.

|

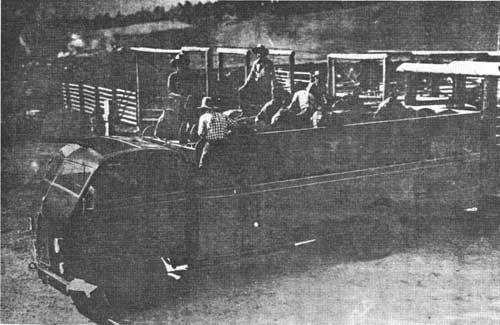

| Mules leaving the Remount Depot for a fire (about 1937). |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/early_days/3/sec25.htm Last Updated: 15-Oct-2010 |