|

Early Days in the Forest Service Volume 3 |

|

REMINISCENCES OF THE DAKOTA NATIONAL FOREST

By K. D. Swan

(Retired 1947)

Automobiles were not in general use for prairie travel when I first rode out to the Dakota Forest from Bowman, North Dakota, in the latter part of April, 1912. Horses were considered a most dependable means of transportation, and forest officers thought nothing of making daily rides of fifty miles or more in the performance of their official duties. To an eastern-bred boy, recently graduated from the Harvard Forest School, this means of getting around seemed fascinating indeed, and it was with elation that I learned the Supervisor had left his saddle horse in a livery barn in Bowman for me to ride out to the Ranger Station. Later I was to ride from there to Camp Crook, the headquarters town of the old Sioux National Forest, from which the Dakota Forest was administered. I became well acquainted later with this Supervisor, Charles Ballinger, a kindly and able man who had the love and loyalty of those with whom he worked.

Spring had touched the prairies as I rode north from Bowman on that bright April morning. There was a shimmer of green on the rolling hills, and shrubs and trees showed signs of leafing out along the coulees. It was an era of homesteading. Many fields had been fenced and planted to grain or flax. I noticed the homes that these newcomers had built some of them made of sod, others covered with tarpaper. I soon learned to detect the pungent smell of burning lignite coal, a fuel which did much to make the settlement of this prairie country possible. I remember seeing a homesteader digging coal from a bank near a coulee bottom. We had a little talk before I rode on.

Before leaving the Regional Office in Missoula (then called the District Office), I was given rather complete instructions as to what my duties would be as Forest Assistant on the Sioux and Dakota Forests. I was to become thoroughly acquainted with the far-flung divisions of the Sioux the Long Pines, the Short Pines, the Ekalaka, the Cave Hills, and the Slim Buttes, for the purpose of preparing a silvical report and an economic plan for the best use of their resources. My duties on the Dakota Forest would deal primarily with planting projects. I was to assist the Ranger in expanding the forest nursery and selecting suitable sites for planting the young trees. I had gained considerable experience the previous fall on planting projects in the Big Snowies of central Montana, and R.Y. Stuart, then Chief of Silviculture in District One felt that this experience might prove helpful in getting a planting program under way on the Dakota and Sioux Forests.

The Logging Camp Ranger Station was on Deep Creek, a tributary of the Little Missouri River. One saw it first from the head of a broad swale which led down from the higher prairie. It seemed an oasis among scoria buttes and badland bluffs on which were growing scattered ponderosa pines and junipers. There was a long one-room building, with a screened-in porch the entire length of the south side, and a substantial gambrel roof barn across the yard at the rear. The small nursery was near the creek south and west of the buildings. This nursery was irrigated by water pumped from the creek, which, as I remember, never ran dry. Green ash and other small trees grew along the stream and provided welcome shade on hot days.

Ralph Sheriff was Ranger in charge at the station. My first meeting with him came as I entered the building and found him taking a siesta on the bed, surrounded by several cats. Ralph was a graduate of the University of Illinois and had come to the western Dakotas with one of his college chums named Haines. The boys had worked for some time building sod houses for homesteaders in the country around Lemmon and Hettinger, and then decided to take the Civil Service examination for the position of Forest Ranger in the United States Forest Service. Both passed. Haines was appointed to help Supervisor Ballinger in the Camp Crook office of the Sioux - Sheriff got the job on the Dakota.

Sheriff was a very capable man; practical and able to do many things well. He was good at handling men and was well liked by all that worked with him. In dress he was quite unconventional, but he was a man of cleanly habits. He was always smiling and nothing ever disturbed him much - a good quality for a forest officer in those days. He was of medium height and rather stocky.

Work in the nursery was in full swing shortly after my arrival. Seedlings of ponderosa pine had to be transplanted from the beds where they had been grown from seed to other beds where they would be evenly spaced and have room to develop until they were three or four years old and ready to be set out in the field. A device known as the Yale planting board was used for transplanting. This consisted of a narrow board with notches in which the seedlings were placed so that the roots extended beyond the edge of the board. Another board of corresponding size was hinged so that it could be closed down on the crowns of the seedlings. When lifted, the evenly spaced seedlings were held securely in place with their roots hanging down so that they could be placed in a trench made ready for them. After the earth was firmed around them, the planting board was opened and removed for another loading of seedlings. The roots of coniferous species are very easily damaged by exposure to drying wind or sunlight and must be kept in the shade during the transplanting operations. For this purpose a rough booth was constructed of canvas tarps.

Homesteaders, known locally as "honyocks," (meaning of term obscure), jumped at the chance to pick up some badly needed cash by working in the nursery. There were several young couples whom I remember well, although I cannot recall all their names. One tall boy, Harry Roberts, was at the time courting the girl he afterwards married. I also remember Joe Miller, and his sister Marjorie, who later became Mrs. Ralph Sheriff. Several older folks also took part.

Travel home at night for most of these people was impossible, so they camped at the nursery. Well do I remember the happy evenings spent around the campfire exchanging stories or listening to music played on the violin and guitar by two of the talented persons of our little group.

After transplanting was finished, considerable field planting was done on various areas in the vicinity of the Ranger Station. I believe one of these areas was on Sand Creek. Planting was done by two-man crews. One man would dig a hole with a mattock; the other would place the seedling and press the dirt firmly around the roots. Many of the seedlings were set in the loose soil on the slopes of the scoria buttes. Rattlesnakes were a menace, and one had to be on constant alert when planting in these locations.

Much of the stock set out in these operations came from the Savenac Nursery in the Lolo Forest of western Montana. It was shipped by rail to Bowman in bales protected by burlap and transported to the Ranger Station by wagon. It is believed that a good deal of this stock was from seed collected in the Black Hills (Pinus ponderosa, var. scopulorum). Eventually, young trees from the Dakota nursery would be used for planting, but at this time no stock of the right age was available from this source.

We felt at the time that the best planting sites were on slopes where some tree growth was already established rather than on areas which were more or less flat and where the seedlings would have strong competition from the prairie grass. I believe that where planting was done on grassy land, the trees were set in furrows made by a sod-breaking plow. In the more rolling terrain where pines of considerable age and size were growing were sites which seemed well adapted for successful planting. There were north slopes which were partially protected from the hot sun and also from the drying winds that swept across the prairie from the south and west. The soil in these locations was more or less loose and seemed capable of soaking up moisture readily. Here, in contrast to the heavily sodded areas, there would be much less grass competition. Whether or not our surmises were correct, I do not know. Studies were never carried to completion, to my knowledge.

Although the time I spent on the Dakota National Forest totaled no more than a few weeks, I grew to love this part of the Little Missouri valley and could well understand the fascination the region held for Theodore Roosevelt when in the eighties he ranched in the vicinity. Near the Ranger Station there was a high point overlooking the river where I often rode of an evening. Here the river made a great bend, and across the valley rose what I think were called the Tepee Buttes. I particularly recall going there one hot evening when the moon was full. That night I had for company Ethel Sheriff, Ralph's sister, an Illinois school teacher out "West" on a visit. Dismounting to enjoy the view, we sat down. There grows in that part of the country a certain species of prickly pear cactus. Oldtimers are well acquainted with it. My companion was not. She did, however, overcome this deficiency immediately!

On Sundays Sheriff would often hitch up the team and we would go on exploring trips to far parts of the forest. Perhaps the most interesting feature we visited was a burning coal mine. Here a bed of lignite coal was burning below the surface of the ground and through fissures we could see the subterranean fire which had already eaten away the fuel under a considerable area, causing the ground to slump as it progressed. How long this coal had been burning, or what touched off the fire was a matter of speculation. The best guess seemed to be that lightning was the cause, but how long ago the strike came nobody that I talked with knew. That the red scoria buttes throughout the badlands are the result of prehistoric fires which cooked overlying beds of clay into a natural brick, seems to be the opinion of the best geologists.

Growing in the vicinity of this burning coal mine are many slender juniper trees which attract attention by their beautiful form. Neither Sheriff or I could account for these trees, but in 1946 when I made another trip to the locality I got the explanation from William Hanson who at the time was majoring in Botany at the University of Montana. He told me that, according to Professor O.A. Stevens of the North Dakota State College at Fargo, they are a hybrid, Juniperus scopulorum columnaris. The original study and classification was made by Dr. Fassatt, a leading taxonomist at the University of Wisconsin.

Sheriff and I often called at the Hanson Ranch, or Logging Camp Ranch, a beautiful spread in the Little Missouri bottoms. At this point ties which had been cut for the Northern Pacific R.R., then building, were dumped in the river to be floated down to Medora. I believe many of these ties must have been cut in the Long Pine Hills. There is a Tie Creek rising in these hills just west of Camp Crook. Possibly some of the ties were also cut from the breaks and swales near the ranch. The operation was not successful, as the ties got hung up in the shallows along the river and the cost of salvage was prohibitive. The name Logging Camp is all that remains as a reminder of this episode.

Other bits of history connected with the Logging Camp Ranch are interesting. We were told that the last mountain sheep in North Dakota was shot from the yard. It was standing on a butte in plain sight from the house. The house itself was hauled overland in two sections from Dickinson by a man of Russian extraction. The move was costly and the man never recovered from the financial loss, so it is said.

The Hansons were good neighbors and always ready to lend a hand where help was needed. Western hospitality in its best tradition reigned at the ranch. To me, these friends exemplified the finest spirit of the true Western pioneer, and contact with them went a long way in helping me, a city-bred bray, to become oriented to a new way of life.

My first visit to the Dakota ended with the conclusion of the spring planting season early in June. On my way to Camp Crook I stopped for a few days in the Cave Hills, meeting the Ranger, Dave McGill, and talking over plans for making a plane table map of his district later in the summer.

Sometime in August, I returned to the Dakota to talk over plans for nursery expansion and to look for new planting sites. It was hot. Day time temperatures above 100 degrees were not unusual. On such days it was pleasant to shade up under the green ash trees out by the creek, or cool off in a small pond Sheriff had made by damming the creek near the station. When making all-day rides in such weather each carried for lunch a size 2-1/2 can of tomatoes tied in a slicker behind the saddle. The contents of the cans would of course be lukewarm, but it would at least quench our thirst as we sat in the shade of a pine or juniper. There were often terrific thunderstorms in the late afternoon of these hot days.

Sheriff had designed the Ranger Station to suit his fancy, and I always felt it was admirably suited to the needs at that time. As mentioned before, it had one room with a screened-in porch on the south. This room would measure, as I best recall, about 35 by 15 feet. In one end was a cook stove. There was also a coal burning heater. Ralph mined and hauled his own coal - the lignite variety - from a "mine" some miles east of the station. This coal, as it was dug had a considerable moisture content, and slacked badly when exposed to the heat of summer.

It also had a high ash content. Some said it should be called "lugnite" for one lugged ashes all night. There was an abundance of pine and juniper available for kindling.

A rough table, bentwood chairs of Government issue, several iron cots, an Oliver typewriter, and a filing cabinet for official correspondence were disposed in a rather haphazard manner in the emptiness of this large room. Water was brought from the creek in pails, which stood on a stand in the culinary end of the room.

Ralph was a good cook and I was not wholly without experience along that line. I remember that on several occasions we feasted on delicious roast pork which came from a nearby ranch. There were always potatoes to be had,, but most of the other vegetables came from cans. It goes without saying that sourdough hotcakes and biscuits were a staple of diet.

The Ranger Station was often used for community gatherings. I shall never forget a dance that was staged during my August visit. Late in the afternoon Sheriff and I hitched up the team and drove to a ranch ten or twelve miles away where we picked up a small organ which was always available for affairs of this nature. Guests from all directions began to arrive at the station about dark. Some were on horseback, some rode in buggies or wagons. It was before the days of baby sitters. All the babies and children came with their parents.

Stout hands moved the stove out into the yard and put the other furnishings on the porch. The organ was moved in and a chair placed for a fiddler who showed up from somewhere. Children were eventually put to bed on the cots out on the porch or in the wagon boxes. Riding stock was unsaddled and tied about the yard or turned into the corral out by the barn. Teams were unhitched and given hay to munch during the long wait. The moon was near full, making it almost as light outside as it was inside the station. The crowded room would not accommodate all the dancers at one time which made for a lot of social activity in the yard where little groups stood around and discussed the coming presidential election, the hay crop, and neighborhood matters in general. Just after midnight, lunch was served by the women. Coffee was made on the stove to which a couple of lengths of stovepipe had been attached. I remember well the picture made by the sparks and billows of black smoke from fat pine surging upwards in the moonlight. All in all, it was a night one could not easily forget.

As dawn reddened the east, some of the women got breakfast, frying bacon, eggs and potatoes which, with bread and coffee, would fortify the men and boys who had to return to a day's work in the hayfields. And so they rode away, this group of friendly people, each feeling, I am sure, a little happier and thankful for this social contact with good neighbors.

Things seemed lonesome at the Station after they were gone. Some of the men had put the stove back before leaving, but Ralph and I cooked no meals that day. We went out to the barn and slept until afternoon!

I made one more trip to the Dakota. It was in December, just as I was leaving for a trip to Boston on my annual leave. I turned my horse out to winter pasture at the station, caught a ride back to Bowman, and boarded a train for Chicago.

|

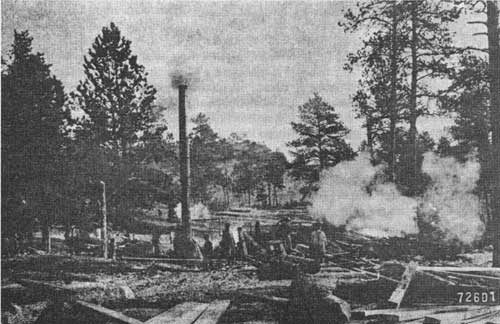

| Sioux N.F., Custer County, Montana — November 22, 1907 — Hall's Sawmill operating under payment in connection with sale. Note no spark arrester on stack. |

|

| Trail Creek Sawmill and pipe conveying the water to wheel. Gallatin N.F. — 1902. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/early_days/3/sec28.htm Last Updated: 15-Oct-2010 |