|

Early Days in the Forest Service Volume 3 |

|

A FEW HIGHLIGHTS OF MY EMPLOYMENT WITH

THE U.S. FOREST SERVICE 1918-1955

By Albert J. (Bert) Cramer

(Retired 1955)

I was born and raised on my father's homestead on the west shore of Flathead Lake and received my grade and high school education in the public schools of Flathead Lake and Sanders Counties, Montana. I graduated from high school in the spring of 1918. Immediately after graduation my younger brother Art and I went to Missoula and volunteered enlistment in the U.S. Marine Corps. Art passed the physical and was sworn in and left immediately for Mare Island training camp, leaving me behind because I had failed to pass the rigid eye test required. This was a great disappointment to both of us because our parents had talked me into staying in school until Art became 18 on June 5, 1918, so we could enlist in some branch of the military service together. However, I was accepted for enlistment in the Students Army Training Corps a few days later and assigned to the University of Montana unit at Missoula.

While I was in the "Trick Army," as we called it, I met up with Chic Joy, Monk DeJarnette, Ralph Crowell and a number of other young bucks who later entered the Forest Service and who are now retired or about to retire. We talked about what we were going to do if and when we got out of Uncle Sam's Army. That is where I first became interested in forestry as a profession. Our Army barracks was just a stone's throw from the little old "shack" at the Montana Forest School. It was here that I first met Dorr Skeels, Charlie Farmer, Tom Spaulding, Peg Lansing, Dick Fenska and other early day Montana Forest School professors who taught Army courses and who built up my first interest in "Forestry" as a college education.

My first job with the Forest Service was immediately after my release from the Army in late November 1918. I hired out as a tree planter and was shipped to Sildax, Montana (on the Coeur d'Alene branch of Nez Perce) where Ranger Frank Haun and foreman Alex ("Cockeye") Donally had a tree-planting job in progress. It snowed about a foot a day or two after I landed on this job but that didn't stop Ranger Haun from getting the trees planted that had been assigned to his district. After trying the snow planting, all but about 10 of the 50 man crew quit within a day. I just happened to be too broke to quit any job at that time so I stuck the job out, being rewarded by free transportation back to Missoula at the termination of the planting job. I was paid off in cash at Missoula by Fiscal Agent Urbanowitz whom many of the old timers remember.

In January 1919 I enrolled as a regular student in the Forest School at the University of Montana and continued my educational efforts there each school year until 1922, accepting Forest Service temporary employment each summer. My first summer was spent as a scaler on the Bitterroot Forest where W.W. White and C.N. Stickney were supervisors and Bill Gee was the District Ranger I worked for.

Although 1919 was a bad fire year in District 1, it just happened that I didn't get in on much firefighting that year. My next summer (1920) was spent on the Flathead Forest where I served as a scaler, timber marker, and fire guard. My bosses during that season were Clyde Webb, Al Rossman and District Ranger Ansley Hutchinson.

While working as Commissary Clerk at the old Hungry Horse Ranger Station, during the latter part of the 1920 season, I met Supervisor Joe Warner and Deputy Supervisors Charles Hash, K. Wolfe, Eldon Vyrick and, last but not least, "Smokey," the "bull-of-the-woods" packer, and Ruby, the lady packer. Ruby was an ex-doctor's dude wife from the East who fell in love with the big out-of-doors and bought and operated a 30-horse pack string between Coram and Big Prairie at that time. "Smokey" was the "Paul Bunyan he-man" type who packed and otherwise looked after the 30 head of pack horses owned by Ruby. Smokey, Ruby and their horses spent several winters at Big Prairie during and just prior to the early twenties. Ruby later became the wife of Ranger Ray Quiman who was District Ranger at Big Prairie at that time.

Joe Warner probably never knew how near he came to getting shot by Smokey on a number of occasions. You see, that big "bull of the woods" got heap mad over Joe meeting Ruby at Hungry Horse and escorting her to Coram a time or two - on official business, of course. Ruby's pack string was being hired by the Forest Service for seasonal South Fork main string packing, but Smokey just couldn't understand that official business idea - or could he? In September 1920 I shot my first grizzly. It happened on Devils Cork Screw Creek on the South Fork. I shot him in the belly with a "38" Colt; a kid's trick; bear got heap mad, started tearing down and busting up the timber. He never found me and I never found him. I never had any desire to shoot another grizzly even though I had numerous chances.

I spent the summer of 1921 on the Moose Creek District of old Selway. Frank Jefferson was supervisor, Jack Parsell the District Ranger and Stanley McKenzie the district packer. I cut and skidded the timber for the first tower on sixty-two mountains and helped build the Parsell honeymoon log cabin at Moose Creek Ranger Station that summer. Jack broke his new bride in right that summer, cooking for the gang, tending telephone, milking the cow, etc., as all good Ranger wives did in the good old days.

In September, W.C. "Cap" Evans and I hiked out to Hamilton via Elk Summit and Blodgett Canyon. Spent one short night (on the floor) at the old Elk Summit Station. Floor space was the best that Ranger Bill Bell had to offer. However, we were thankful to have even a roof over our heads since it rained and snowed like hell every hour of that two-day and two-night trip. By cabin talk at Elk Summit, Cap and I learned that Bill Bell was very mad at Regional Forester Fred Morrell; and when Bill Bell got mad, he got mad all over. It seemed that Bill had loaned Fred a saddle horse belonging to Bill's sister. The horse had just been returned to Elk Summit that evening and was somewhat spur marked. No doubt a lazy pony and Fred was in a hurry, hence a lot of urging was necessary. When Cap and I got our last pay checks we got mad too. We had been allowed only two days' travel time for the trip from Moose Creek to Hamilton while the Idaho ("native son") boys who walked out to Kooskia got either 3 or 4 days' travel time. In other words, there was discrimination in favor of the Idaho boys. Only natural, I guess, but a boy just doesn't like or forget that sort of treatment. It should not be practiced.

During the school year of 1922 I married Johanna Guettler of Missoula and at the end of the winter quarter of school I accepted a probational appointment as Surveyor Draftsman ($1220 per annum) with headquarters at Missoula. I was just three months from graduation. I planned on going back to finish within the next year or two but never made it to this day. Just had to keep my nose on the grindstone, it seemed. During the field season of 1922 I helped Harold Townsend, Dick Hilleary and Jack Ray revise and improve the drainage map of the Kootenai. Art Baum was the boss on the Kootenai at that time. Bob Byers, who was the Ranger at Rexford, had his eye on that cute little gal in the Supervisor's Office (Adelaide Erdman) but still didn't convince her that she should change her name to Adelaide Byers until some time later. Spent the winter of 1922-23 in the district engineer's office in Missoula, completing the office end of the Kootenai mapping job. Took the Forest Assistant and Forest Ranger Civil Service examination during the calendar year 1922. Got a grade of 65 in the Forest Assistant exam and 95 in the Forest Ranger examination.

On April 23, 1923, I accepted a $1220-per-annum probational appointment as Forest Ranger and was assigned to the Wolf Creek District of the Blackfoot Forest with summer headquarters at Fairview Ranger Station, and winter headquarters at Kalispell. I loaded my young wife, Jo, my young son, Albert, and our dog, Dewey, into a second-hand Model T and headed for Fairview Ranger Station, located on Wolf Creek 60 miles by dirt road west of Kalispell. Les Vinal was supervisor and Charles Hash, deputy supervisor of the Blackfoot at that time. A two-room log cabin, located on the bank of Wolf Creek, served as living quarters, office, warehouse, etc. This is where my good wife served her apprenticeship as cook, clerk, telephone operator, and fire dispatcher, in which capacity she was privileged to serve, without pay, over the next eight years on four different Ranger Districts. Two more sons, Bob and John, arrived while we were assigned to the Wolf Creek District.

In the fall of 1925 I received a promotion to the Fortine Ranger District, which was the top-rated district of the Blackfoot Forest at that time. My new salary, as I recall, was $1800 per annum. I herded my milk cow about 40 miles over the Wolf Creek-Fortine divide by trail to my new headquarters at Ant Flat Ranger Station, where I replaced I.R. "Jinks" Jensen as District Ranger. It was here that I became quite closely associated with Fred Herring, who at that time was serving in semi-retirement as Assistant Ranger of the Fortine District. Fred was one of the truly and colorful old timers who had a hand in making early-day Forest Service history in the Flathead locality. Fred was a ranch hand in the Dakotas in the pioneer days for Teddy Roosevelt, and served with Teddy during the Spanish-American War in his Rough Rider Brigade. I have been told that one of the early-day supervisors at Kalispell "tied the can" to Fred over a drinking party. Theodore Roosevelt was President at the time. I guess Fred wrote Teddy advising him of his predicament. The Forest Supervisor got a letter from "the boss" stating briefly, "Put Fred Herring back to work." Fred was back on the job without loss of pay, as soon as they could find him, and stayed until his official retirement in 1927.

During July, August and September of 1926 I got my eye teeth cut in big crew firefighting. Jim Ryan and Ray Fitting were my supervisor and deputy at that time. The Forest Service never had two better firefighters than those two old timers. Believe me, we had some good old lumberjack crews who knew how to handle the crosscut saw, double-bitted ax, and hodag, and we also had some good old lumberjack foremen who could get the jobs done even though it all had to be done the hard way. I was just a kid in my twenties, with practically no big fire experience, when the big Stryker fire broke on my district and spread to a 10-mile length and three-mile maximum width the first day (July 31). Believe me, I had gained a lot of big-fire experience by the time I awakened one morning in September with about one foot of snow on top of my bed on the headwaters of Shorty Creek, where I was heading up a 300-man crew on the head end of the Stryker fire, with no method of getting messages to or from the outside world except by foot or horseback. My alternate, J.E. "Slim" Cluzen, (retired 1957), had a 50-man lumberjack crew on that fire within about one hour after an 11 a.m. discovery, but couldn't hold it. That was exceptionally quick and heavy manning in those days. My opinion is that present-day bulldozer and airplane bombing could have caught that fire at five acres or less and saved thousands of blackened acres. However, I would not want to back that opinion with more than 50-50 odds.

Following the season of 1926 I had the honor of serving as a guinea pig on what I believe was the first detailed and exacting work plans preparation job done in District One of the Forest Service. Earl Loveridge from the Washington Office and my supervisor, Jim Ryan, spent ten straight days or so at my district headquarters analyzing my calendar year 1926 diaries and writing up detailed work plans for the ensuing year. I recall that my diaries disclosed I worked better than 10 hours a day and Sundays throughout the 1926 field season. I also vividly recall what a nightmare the 1927 season turned out to be, with me duty bound to make an honest effort to live up to and carry through with all the detailed daily trip and work scheduled which had been guessed at and written up several months before the field season began.

Looking back on all my experience with Forest Service work and trip plans, I don't believe that I am wrong in saying that work plans have been responsible for many gray hairs and thousands of ulcers. Sound and timely planning has a great deal of merit and value, but, in my opinion, the Forest Service has wasted a hell of a lot of man-hours and burdened a lot of good men with worthless and useless paper planning, and useless records, just to satisfy the desires of some crackpot plans expert somewhere up the line. Back in the good old days, forest officers were rugged individuals, who were handed a job, "lock stock and barrel," and then held responsible for accomplishments. We had the old Use Book and one small manual of laws and regulations in which one could find most answers that were worth while. In late years the forest officer has become so burdened with volume on top of volume of rules, regulations, work plans, instructions, etc., etc., that he becomes office bound and confused. Too many higher-ups trying to justify their existence make it hell for the underdog and discourage strong leadership. The Forest Service would get along better and accomplish more on-the-job results if it would dispense with a lot of pencil pushing positions all along the line from the Chiefs office down to the District Rangers and put that money into allotments for on-the-job accomplishments.

During a number of years prior to the time I took over the Fortine Ranger District, considerable trouble was experienced with incendiarism in the Pinkham Ridge and Pinkham Creek locality which is along the western boundary of the Fortine District. This situation became so serious that armed guards were placed in the area throughout one season. This was just prior to the time that I took over this district. One day in 1927 my alternate ("Slim" Cluzen) and a crew extinguished a small fire which was obviously of incendiary origin. This fire was on or near the homestead of one of the old Pinkham Ridge ringleaders - a man reputed to have several notches on the stock of his gun for men he killed before he came to Montana from West Virginia. The next day I was all set for more fires in the same locality. Sure enough, about noon a couple more smokers showed. Cluzen and I both went to these fires with a crew. It was obviously another incendiary attempt. After we controlled the fires, Cluzen and I went to the home of Frank Moore, who was our prime suspect. I left Cluzen on guard at the edge of the clearing surrounding the house. I proceeded to the house and knocked on the door. All was perfectly quiet; there was no response to my knocks. Finally I opened the door. A strong moonshine odor came from the room. I observed a moonshine still operating in that room. I stepped to the door of a second room and observed Frank Moore lying on his bed dead drunk from his brew.

Cluzen and I shut off the burner under the still, loaded Frank Moore in my car and took him to Eureka, intending to arraign him before a court on a charge of incendiarism. All we could get out of him was the occasional remark, "To hell with the fires." Upon our arrival in Eureka our prisoner was still too drunk to be taken before a court so we put him in the city jail over night to sober up. The next day, Frank Moore pleaded guilty as charged and the court assessed the customary fine. The prisoner pulled a roll of bills from his pocket that would choke an ox and paid his fine. I then asked Mr. Moore if he wanted a ride back home since Cluzen and I were going that way. To my surprise, the old, hard-boiled hillbilly accepted my offer. Enroute home he asked what I had done about the still that I had found in his house. I told him that we had shut off the burner when we left the house the afternoon before and that I intended to forget all about the moonshine business as long as he confined his operations to his own property. I had no more fire-brig trouble while on the Fortine District. In fact, Frank Moore did blacksmithing for me and became quite friendly after this set to. I understand he want to the state penitentiary some years later for butchering a beef that didn't belong to him. My motto: "Mind your own business." I could have reported that still to liquor-law enforcement officers, but I didn't. I was not obligated in any way to report stills on private property.

During the winter of 1926-27, Ranger L.E. "Les" Eddy, Deputy Game Warden Archie O'Claire and I made a snowshoe trip into the Frozen Lake-Wigwam country along the Canadian line in the large primitive area north of Fortine and Eureka, Montana. A report had come through the Queen's office in England to the U.S.A. to the effect that some Canadian halfbreeds were conducting extensive beaver-trapping operations on both sides of the International border. We were warned that these trappers were dangerous men. It turned extremely cold the next day after we took off from Ant Flat Ranger Station on snowshoes, armed with rifles and about 3 days' light provisions, two small tarps and one blanket. We spent about ten days on that trip. The thermometer dropped to 50° below zero and stayed around that figure throughout the trip. It was luck that we had plenty of salt along because it was salt and the rabbits and birds that we could kill each day that pulled us through. We stayed the first night out in an old cabin, the most miserable night of the ten spent on the trip. We came home with our belts tightened up considerably but feeling like a million dollars. The only fresh tracks, big game or human, that we observed on the entire trip were those of a big grizzly bear that was traveling in or on 12 feet of snow without snowshoes. Game Warden O'Claire called this sort of trip and results "a water haul."

I was transferred to the Plains District of the Cabinet Forest in the fall of 1928, and then to the Noxon District when Ben Saint "bunched it" in the spring of 1929. Ray Fitting was the supervisor of the Cabinet at that time. I recall only two rather exciting experiences while on the Cabinet. One was when a big mother black bear made for me and I killed her with one bullet from my "22" Colt placed accidentally in her right eyebrow. My little dog had run her cubs up a tree. The mother bear jumped on my dog and I very foolishly tried to help the dog. The bear was about 10 feet from me and coming right at me when I pulled the trigger. Very much to my surprise she fell dead on the first shot. I have had several bear, including grizzly, stand me off and try to bluff me but that is the only one that ever made for me, and it was very clear that she meant business.

On another occasion I was down along the Clark Fork River between Noxon and Heron checking on reports that Jap extra-gang men were doing a lot of fishing. They were all aliens and the local folks wanted me to stop this fishing. When I sneaked out to the river banks I could see at least 20 Japs, all fishing. One fellow was right down under the bank on which I was standing. I went down and proceeded to arrest him. While trying to convince this Jap that I was placing him under arrest I could see the other fishermen dropping their poles and disappearing in the brush. As my victim and I got back up to the railroad tracks all those 20 Japs who had been fishing surrounded me and my prisoner and started talking Jap to beat hell. They sounded very threatening and convincing. About the time I could feel numerous knives tickling my back, another Jap came running up the track. He spoke good English. I told him that I had arrested this one man for fishing and that I wanted to take him to Thompson Falls to the court. He told me he was a foreman and that he would see that this man was available if I would come to the extra-gang cars about 7:00 a.m. the next morning. I was there the next morning at the appointed time but could not identify either the foreman I had talked to or the fellow I had arrested. Just another "water haul." I have often thought how lucky I probably was that I was not armed with a gun when I went out that evening to check on the fishing by the Jap extra gang. I may have tried to use the gun and someone would most likely have gotten hurt, so it was best the way it worked out.

I have my diaries back to 1931 only, so am not sure of the year, but believe it was during August 1930 that I had a string of fires set along the country road leading from Heron toward the Idaho divide trail up Jack's Gulch. It just happened that I was at the Noxon station when this report came in so I went to the fires with all available men. Upon arrival it was immediately evident that they were deliberately set by someone. I followed tracks from one fire to the next, and next, etc.

The tracks finally led out into the dusty county road and up the road toward Jack's Gulch. At the end of the county road the same fresh tracks continued on up the Jack's Gulch trail. I called Supervisor Fitting from an emergency telephone at the end of the Jack's Gulch road and advised him of my intentions to follow those tracks which I believed were those of an incendiarist. I suggested he call the Coeur d'Alene supervisor, advise him of my suspicions and intentions and ask him to send someone out from Magee Ranger Station to intercept the suspect, or at least meet and help me in what I was attempting to accomplish.

After phoning Fitting I took off up the Jack's Gulch trail in high gear. I followed the suspect's tracks about 12 miles across the Montana-Idaho divide and down to within a couple hundred yards of a cabin on Independence Creek, known as the Planting Warehouse. At that point the tracks left the trail. I checked the cabin and all trails leading out from the cabin. I found no further tracks. The cabin was locked and all shutters were in place on the windows. It was about midnight by then so I decided to spend the rest of the night in the cabin and continue my search for the suspect in daylight.

I unlocked the cabin and found and lit a couple of candles. I then noticed something in one of the bunks which resembled a man's body covered with blankets. I pulled the blankets back and, low and behold, there was a wide-awake man staring at me in the dim candlelight. It sort of startled me because I had checked for signs of anyone's forcibly entering the cabin and found nothing to indicate that this was the case. I asked the stranger if he had any objection to my occupying the cabin with him for the balance of the night and he said, "Sure, that will be o.k." I did not identify myself or question the stranger that night concerning how he got into the cabin, who he was, what he was doing in the locality, etc. I ate a bite, rolled into the top bunk above the suspect, and pretended to sleep, but I was actually just waiting for daylight. By this time I was sure I had a "firebug" on my hands and was determined that he was not going to be permitted to set more fires, regardless of what I had to do to restrain him.

About 3:00 a.m. I heard horse hooves pounding the turf near the cabin, and in just a jiffy Deputy Supervisor Ashley Roach came to the door, flashed a light on me and said, "Is that you Cramer - did you find the firebug?!" Ijumped out of bed without answering the question, went outside and held a brief, whispered conference with Ashley, followed by another secret conference somewhat later. We decided to arrest the stranger and, providing he did not resist, I would take him back across the Montana-Idaho Divide which was by far the shortest distance to road and car transportation.

After a breakfast of short rations we placed the stranger under arrest. Upon searching him we found nothing in his pockets except a small bar of soap, some matches, a short fish line, and one fishhook. The man denied setting any fires, and claimed to be a mining engineer prospecting for minerals. I hiked the man ahead of me back to my car at Jack's Gulch where I telephoned Supervisor Fitting, and he in turn consulted Attorney Charles Brothers at Missoula for instructions. Mr. Brothers advised that we erred in bringing the man out of the state in which we had arrested him. Fitting and I said we would take him back into Idaho by car. Mr. Brothers said, "You can't do that, it would be illegal, you will just have to turn him loose." We told Mr. Brothers that, legal or not legal, we were not going to turn him loose and were taking him back into Idaho.

I then proceeded by car to Heron where Fitting met me, another secret conference was held and it was decided I should head for Coeur d'Alene with my prisoner. Upon arrival in Coeur d'Alene the prisoner was arraigned before a U.S. Commissioner and officially charged with willful setting of fires. A short time later a sanity hearing was held in a Federal Court at Coeur d'Alene and the man was placed in a Federal asylum where he spent the rest of his life, I believe. The end of another firebug's career.

This case was a good example of how a forest officer can get up against making vital and important decisions in the backwoods. We made the mistake of illegally taking this man across a state line while he was under arrest and before he was arraigned in court. There could be no question but that getting a firebug out of the woods and keeping him out was morally right, so the thing to do was to take him back into Idaho and worry later about the legality of our actions. Our legal errors were never brought up or questioned either by the defendant or the prosecuting attorneys.

I was transferred to the Pend Oreille Forest in North Idaho on April 4, 1931, and was assigned to the Sandpoint Ranger District. Ray Fitting was the supervisor and Albert Cochrell the deputy supervisor. The fire season of 1931 was a nightmare. I started fighting fire on my own district in May, and was called to the Deer Creek fire north of Bonners Ferry, Idaho, on July 26. On our way to this fire we could observe the cauliflower top on the fire, indicating it was going places. I was in charge of various sectors of the Deer Creek fire; there were some good and a lot of bad results. Hundreds of miles of fire line were built, hundreds of miles of line lost, and at least some incendiarism to contend with, including the initial setting of this fire. I was finally released from this fire on August 15 by Supervisor Clyde Webb of the Kootenai Forest. He brought Ranger Bert Bealey to my camp near Pete Creek Meadows on the Kootenai Forest and placed him in charge. That camp was near where the fire crossed the Canadian line and continued on into Canada, at least 30 miles airline from where the fire started.

I will never forget one night during this 20-day fire assignment. I had about 300 men camped in a big meadow. The fire seemed to be coming in on us from all sides, which was unusual. I am sure there were firebugs working that night. I fed the entire crew before dark and put all men back out on the fire line again because it seemed that we were going to have to fight to save our camp. About midnight a tall white pine snag struck one of my men squarely on the head, bursting his head in two pieces and literally driving him endwise into the ground. I pulled the entire crew into camp and told them to hit the hay. I found a bedroll and just passed out. The next thing I knew Regional Forester Evan Kelley was shaking me and peering down into my face. It was daylight. As soon as he got me fully awake, he said, "What the hell is wrong - kill one man and order 500 to replace him." The Major then informed me that the sight of this dead man when they carried him into camp the night before had apparently caused my timekeeper to blow his top, resulting in his jumping in a car and driving to Bonners Ferry and ordering 500 men and equipment for my sector of the fire. The Regional Forester just happened to be in the Sandpoint office when this order came in and thought he had better come out and see what was going on. As it turned out we didn't need or get the 500 men the next morning, but I will agree that it looked like we would need a thousand men when the firebugs were working the evening before.

The afternoon of August 3, 1931, Supervisor Jim Ryan called and wanted help on the big Freeman Lake fire which was going hog-wild. That fire had started near Freeman Lake and traveled several miles that afternoon to a point where it was threatening to destroy the Priest River Experiment Station by that first evening. This fire fooled everyone by spotting across wide ravines, burning a number of ranch homes and other buildings which were normally considered fireproofed by their surroundings. I picked up a 30" x 8" x 2" thick cedar shake about 6 miles from where it was known to have been torn from the roof of a barn that burned. That scorched shake had actually been torn from the roof and thrown that distance by the force of the heat and wind during the time the fire was making its big run that first afternoon.

I learned a lesson the first day on this fire which I have never forgotten. My 50-man crew and I became trapped by a blowup behind us. A big,?mouthy strawboss that I had immediately started to try to outrun the blowup and take my crew with him. I knocked a handle out of a grubhoe, stood my ground in front of this strawboss and the crew and threatened to crown the first man who tried to pass me. In just a minute or two this strawboss and the crew saw what would happen to them if they did not obey my orders. I took the crew into a nearby crowned-out area where it was still hot and smokey but safe, and no injuries resulted. Experience paid off again.

The evening of August 25, 1931, I got called to the big McPherson fire that was coming off the Magee District of the Coeur d'Alene and onto the Noxon District of the Cabinet. George Duvendack was District Ranger at Noxon. Assistant Regional Forester Glen Smith was placed in charge of the Cabinet end of the fire. It was on this fire that I first met Axel Lindh and a number of other Region Six overhead. I was released from the McPherson fire on September 5, and the next day another bad railroad fire broke out near Sandpoint.

I will never forget the close call about 50 men had on that fire. This crew had established a line across a canyon at the head of the fire and were holding it. Supervisor Ray Fitting was watching the fire from the window of the Supervisor's Office in Sandpoint. About noon he became convinced that the fire was getting set for a big blowup that afternoon. He sent a messenger with orders to pull all men off the front or north end of the fire and be prepared for blowup conditions that afternoon. The orders to pull all men out of the canyon at the north end reached the foreman and sector boss of the canyon crew just in time. They abandoned the line and rushed down the canyon to the shore of Lake Pend Oreille where they waded out into the lake as far as possible and put fires out on the shirts of one another, with the flames from the fire burning the green leaves off the cottonwoods almost over their heads. There can be no question but that years of experience and mature judgment paid big dividends on that occasion.

The mature judgment gained by the old timers through years of experience has been a blessing to the Forest Service over the years. The young foresters of today who are taking over from the old timers must not overlook the extreme importance of developing men along these lines, and seeing that at least one of them keeps in close touch with big fire situations at all times. All of us who have fought a lot of big fires have had numerous close calls. Experience, mature judgment and foresight have saved human lives hundreds of times. I repeat, keep a generous supply of that sort of fire overhead developed and on the job at all times. With modern fire weather forecasting and communications, which we did not have even 25 years back, there is no excuse for not recognizing blowup conditions and taking action which will prevent disasters such as the Mann Gulch fire where 13 smokejumpers perished.

During August 1932 I had three fires reported in the Carywood locality. I went to the fires with three men. suspecting there was something wrong about three fires showing all at the same time. Upon arrival at the first fire I found fresh tracks nearby. The footprints had easily identifiable print patterns customarily found on rubber-soled shoes. By taking lots of time I was able to follow the tracks from the first to the second and on to the third fire. From the third fire the tracks led westerly across a 40-acre brush flat and out across a plowed field directly to a farmhouse. By the time I reached the house I had firmly made-up my mind that if I found a man with those easily-identifiable soles on his shoes I had my "firebug." By the time I reached the house I was getting mad; I had had so much trouble with this sort of fire and so little success in getting confessions because of handling the suspects with kid gloves. I was also disgusted with how the attorneys would prosecute only lead-pipe-cinch cases, with the consequence that Uncle Sam was stuck for all costs on numerous fires of this sort.

As I approached the house I noticed many tracks of the type I was looking for in the dust around and near the house. The man who responded to my knock on the door was wearing a new looking pair of tennis shoes of the type suspected. I informed the man of the fires and he pretended to know nothing about any fire in that locality. I decided I might have to get rough with this fellow, and since I didn't want to have both him and his wife to handle I invited him to go with me to a point behind his barn from where I could show him the smoker. He fell for my suggestion. On our way to the barn I observed that the tracks the suspect was making were identical to tracks I had trailed from all three fires. I was really getting mad and determined. When my suspect again denied any knowledge of the fires I just couldn't keep my hands off him any longer. I grabbed him right by the shirt front with my left hand, and with my right fist clenched and drawn back ready to strike I told him a lot of things in a very short time. I don't know what all I said but it must have been convincing, because within a half minute or less this full grown man of 50 years started to cry like a child. He confessed that he had set all three fires that morning in hopes that they would spread over all of his and adjoining range which was brushed up quite badly.

I took the man to the fires and had him tell his fire-setting story to my crew and then had him sign a written confession with the crew as witnesses. About 15 days later the District Judge at Sandpoint gave this man the minimum sentence of 60 days in jail. The judge then gave the confessed "firebug" and a number of his neighbors who had been character witnesses at the hearing, a good, sound 10-minute fire lecture. At the conclusion of the lecture the judge suspended the sentence and told the farmer to go home to his family. This farmer shook my hand, and with tears streaming down his cheeks thanked me for what he called "extremely fair treatment," and assured me that I would have no more trouble with him. I had no more fire-setting trouble in that locality.

In August 1934, I was called to the big Pete King fire on the old Selway Forest. I was told that an airplane would pick me up at Sandpoint. Even though I had fought a lot of fire at home that season, I was thrilled when the call came because it involved my first airplane ride. I traveled in style to that fire in an open cockpit plane. I put in the next four weeks fighting fire on a number of different sections, winding up the season at the Falls camp on the Selway River on September 7, when the first general rain finally cut loose.

I will never forget how sick I was when I was released from that fire assignment. The stomach trouble, which most all of us had when we left that fire, was traced to the fact that the fire got so big that nearly everyone had to live, eat, sleep and work inside the burned area and drink the fire ash and lye-impregnated water, not for a few days, but for several weeks. I never fully recovered from this sickness and finally on January 9, 1935, I submitted to surgery in a Spokane hospital for stricture of the esophagus. My doctor blamed my throat trouble to irritation started in the esophagus by the fire ashes swallowed and lye-impregnated water drunk while fighting fires during the 1934 season. I was hospitalized 20 days, using all my 15 days sick and 15 days annual leave, before I was able to get back on the job. I paid all the doctor and hospital bills and am still living with an abnormal and bothersome esophagus.

I suggested to my Supervisor that this should be a compensation case but he was unable to convince the higher ups that it would be approved, so the matter was dropped. I will always feel that this was an injustice to me that would not be dealt out to a forest officer today. The Forest Service has become more considerate and humane in recent years. I have heard old timers say many times that the Forest Service was more considerate of its horses and mules than of its personnel in years past.

This reminds me of another incident along this same line. During one summer season while I was District Ranger at Sandpoint. Idaho, one of my smokechasers almost drowned. Alternate Ranger Donald R. Nelson and Headquarters Smokechaser David Harris, after coming in from a dirty fire, decided to take a swim in the Clark Fork River after supper one evening. After washing their bodies at the water's edge near the old wagon bridge, both of them dived into the river and swam in approximately the center of the river channel. Both were expert swimmers. The river is close to 500 feet wide at that point. All of a sudden Don heard Dave call for help. Don looked around just in time to see Dave go out of sight with his arms spread wide apart as if in cramps. Don swam to where he estimated was the spot where he saw Dave go down and dived several times looking for Dave. Finally Don became completely exhausted and had to swim to shore to keep from going down himself. Don spent a minute or so on the river bank beating his arms across his chest and otherwise exercising, and dived back into the river. He swam to where he believed he had seen Dave go down and began diving and looking for Dave again. Finally, by sheer luck, he located Dave lying on the bottom of the river. Don swam back to the river bank with Dave in tow. Dave's body was turning black and very rigid by that time. Don had recently taken Forest Service first-aid training and lost no time in starting artificial respiration. Don says that after what seemed to be fifteen to thirty minutes Dave's body began to limber and soften up and he finally regained consciousness. Dave spent the next couple of days in bed but fully recovered within a few days.

I have repeated the facts concerning this near serious accident as related to me by Don and Dave the day following the incident. Knowing these two men as well as I do and also the river and water conditions under which this rescue was made, I wish to say that Donald R. Nelson performed a Herculean and heroic task in locating the body of David Harris on the bottom of the river and in getting Dave to the river bank. Dave Harris can thank his lucky stars that a young "bull-of-the-woods" like Don Nelson was near him and saw him go down. There is not one man in a hundred who would have had the physical ability to make this rescue, to say nothing of the guts and whatever else it took to accomplish this job. Dave Harris can also be thankful that Don understood how to administer artificial respiration; otherwise it would have been taps for Dave.

I reported this near serious accident to the Forest Supervisor. So far as I know, to this date nothing further was done toward giving Don Nelson some sort of official recognition of this heroic deed. I wonder if it is too late still to do something along that line. It is my understanding that medals are given for heroic deeds of this sort. If that is correct I believe Don Nelson is entitled to be awarded a medal. Don Nelson is at the present time a successful rancher living near Plains, Montana. David Harris, a World War One veteran, and father of a large family, lives on his homestead near Clark Fork, Idaho, I believe.

I was promoted to Chief Ranger on December 1, 1936, and assigned to the Supervisor's staff of the Lewis and Clark Forest. R.T. "Fergie" Ferguson was just replacing Bill Willey as Supervisor at Great Falls, and Adolph "Wee" Weholt was Deputy Supervisor. I was placed in charge of fire control improvements and wildlife management. It was here that I met old time District Rangers Dave Lake, Emory Wilson, Stacy Eckert, Lester McLean, Walt Streeter, Lawrence Howard, and Tom Wiles. A fine bunch of fellows, all from the old school. Fred Kennedy replaced Weholt and George Duvendack moved to the Choteau District within the next couple of years. They were young sprouts like myself at that time.

The season of 1936, when almost the entire Little Rockies Divison burned, demonstrated that eastern forests will burn. This was true of the 1940 season also. I wish to say that I was on a big percentage of the large fires of Region 1 from 1919 to 1955, and none of them burned more fiercely or were more dangerous than the Hungry Horse and Teton River fires on the Lewis and Clark in 1940. The 1936 Little Rockies fire was another example of a very dangerous and rapid-spreading fire. Don't ever underestimate the potentialities of eastern Montana fires in bad years.

In the spring of 1941 I was promoted to the position of Regional Law Enforcement Officer and transferred to Missoula. I enjoyed this work, and in my opinion, accomplished a great deal of good, sound law enforcement work during the next ten years. I could write a book recording interesting and worthwhile law enforcement accomplishments during that period. However, this write-up is already getting too long so I will close this period mentioning a couple other incidents.

While in Virginia City one day I met and shook hands with a sheriff whose name I can not recall at this time. He asked me if I was a brother of an Art Cramer who back in the 20's was Ranger at Ennis. I told him Art was my kid brother. The sheriff shook my hand again and said, "I want to tell you Cramer, that brother of yours had the most guts of any man I have ever known." He then recited the circumstances of how Art had called him one day to report that a sheepherder on one of the Forest Service sheep allotments had gone nuts and had run the owners of the sheep off with a rifle, threatening to shoot anyone who tried to come near his sheep wagon or bother his sheep. Art asked the sheriff to go with him and arrest this crazy man and put him where he belonged. The sheriff accompanied Art to the sheepherder's camp. They were both armed with rifles. As they came within sight and rifle range of the camp it was agreed that one should stay by the car and the other walk up to the herder's wagon and make the arrest.

Although it was actually the duty of the sheriff to make this arrest, Art volunteered and insisted it was his duty to approach the herder and disarm him. The sheriff covered the herder with his rifle, with the car as a shield, while Art approached the sheep wagon. The herder aimed his gun at Art as he approached and shouted numerous threats, but Art just kept on walking straight toward the herder while trying to reason with him. The sheriff said he didn't know how he kept from shooting the herder to save Art's life because the herder kept shouting threats and aiming the rifle right at Art's guts. Art finally grabbed the rifle right out of the herder's hands.

If Art were alive I feel sure he would object to my putting this in writing. However, I believe episodes of this sort are worth recording and I doubt if this one has been. I believe all who worked with Art over the years realize that he had guts and also lots of what it took to get the job done. Also, even some of the higher-ups with whom Art tangled at times, will have to agree that Art's work saved a lot of topsoil for future generations in both Region 1 and Region 2. It is too bad that he could not have lived to enjoy a few years in retirement and do a little writing about his experiences and the pursuit of his ideals.

On September 19, 1951, I got notice from my boss in Missoula that the Chiefs office was insisting upon termination of my official position as Investigator and offering me a transfer back to administrative work in Region 1. This notice fell on me like a bomb out of a clear sky. I was 52 years of age and had planned to stay in Forest Service investigative and law enforcement work for probably another 10 years, and then retire as a Federal Law Enforcement Officer under an August 25, 1949, amendment to the Federal Retirement Act (5-USC-691-Par. d). This would have been far more to my advantage than retiring as a regular forest officer. I was thus forced to make an almost over-night decision as to whether to accept a transfer back to an administrative position, thereby losing the special law enforcement officer retirement rights I had accumulated, or to apply for immediate retirement on the basis of a law enforcement officer. The advantages of retiring as a law enforcement officer wherein, with 30 years' service at age 50, full-pay credits applied, were very obvious so I decided to apply for retirement rather than accept a transfer to an administrative position on some Region 1 forest.

Finally, on October 3, after a great deal of work and wonderful support from all fellow workers and bosses in Region 1, my retirement application went to the Chiefs office, supported by volumes of statements, etc., etc. Finally on October 18, after numerous wires, telephone calls, etc., between the Regional Forester's office and the Chiefs office, I was given notice that my retirement application had been disapproved and immediate transfer to the supervisor's staff of the Coeur d'Alene was the only way out. I reluctantly agreed to this transfer with the definite understanding that the transfer was not to jeopardize my rights to retire at some future date on the basis of my service as a law enforcement officer.

On December 6, 1951, I loaded my wife and 30 years' gatherings into my car and headed for the Coeur d'Alene Forest, where I served as fire, lands, range and wildlife staff officer until my official retirement at age 56 on May 31, 1955. Before applying for retirement in 1955, I asked a U.S. Senator to check into and ascertain why my 1951 application for retirement as a Federal law enforcement officer was not approved. After several months' investigation the Senator came up with the answer that my 1951 application was not approved by the Civil Service Commission because it came to them without the approval of the Chiefs office of the U.S. Forest Service. I don't mind saying that this information, cut me deeply and made me mad enough to head straight for Washington, D.C. and twist a few noses.

I greatly appreciated how wonderfully my coworkers in Region 1, who had just heard knowledge of the facts, had gotten behind and approved and pushed my application for retirement as a law enforcement officer. It was hard to realize that the "big shots" in our Washington office would absolutely disregard regional recommendations and disapprove my application, thereby beating me out of approximately $100 per month retirement pay which I was honestly entitled to for the rest of my life. I have my ideas but will probably never know just why the Chiefs office insisted upon terminating the position of Investigator in Region 1 in 1951. Could it be that I shot too straight and refused to pass up or wink at facts in certain fire cases to which I was assigned to get and record the facts but was later called off for some unknown reason? I realize now that I made a serious mistake by agreeing to accept a transfer back to administrative work in 1951, thereby relinquishing the retirement rights which I had accumulated while working as a law enforcement officer.

I have all my diaries for the last 25 years of my 36 years' service. I have recorded a few highlights of my 25 years as an administrative officer. The many interesting and unique experiences during the ten years I was assigned as regional law enforcement officer for Region 1 would make this write-up too long, so that will have to be another story someday.

In closing, I wish to pay tribute to the hundreds of wonderful Forest Service men and women with whom I have worked and associated down through the years. Most of them have by now retired and many have passed to their reward. Even though I have voiced criticism, registered complaints and made suggestions for improvements, I realize fully that the Forest Service is in good hands. My wife and I have no regrets that we were for many years members of this fine organization. We point with pride to Forest Service accomplishments over the years with full confidence that the good work will continue.

|

|

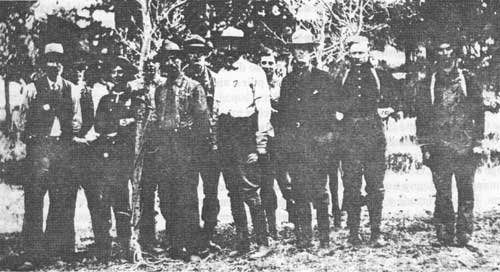

Timber-marking group on Cooper Sale on Mill Creek, Yellowstone Forest

Reserve, Absaroka Division, 1906. 1. Cal West, Ranger 2. Allen, a visitor 3. Yerkes, Ranger 4. John Keach, Forest Assistant 5. E.C. Russell, Forest Supervisor 6. Bert P. Kirtland, Forest Assistant 7. Gifford Pinchot, Forester (Chief) 8. Harry Kaufman, Ranger 9. Thos. H. Sherrard, Asst. Forester 10. ______ Ramsey 11. _______Coley, Laborer |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/early_days/3/sec4.htm Last Updated: 15-Oct-2010 |