|

Early Days in the Forest Service Volume 4 |

|

BACKFIRE

(The Martin Creek and Pete King Fires)

By L.A. Williams

I was a District ranger with the U.S. Forest Service in 1934, in northern Idaho. Assigned to the St. Joe Supervisor's staff, heading up reforestation, fire control studies and timber management. That year was probably the worst-fire year the region ever experienced. Probably worse than 1910. However, elaborate fire and burning condition records were not available for 1910 as the Forest Service was but a lusty infant at that time. By 1934 it had grown to a rather large and experienced organization with an enviable fire record. Nevertheless, they had had several bad fire years previously, such as 1925, 1929 and 1931. Thousands of acres of forest land had burned in those years.

It was mid-August and burning conditions were very explosive. Worst of all in the Selway-Bitterroot Primitive area where no rain had fallen since March. There were several large fires burning throughout the Region. The atmosphere had become so smokey that sometimes fires were a half section in size before even being detected.

I was on detail at the Regional headquarters in Missoula, doing some work for the Chief Forester's office. One evening the Fire desk called me and ordered me not to leave my hotel room without permission. They stated I was being sent to the Selway-Nez Perce to take charge of a fire that had exploded that afternoon. I was to go to the Moose Creek R.S. by plane next a.m. if the planes could get through the smoke. The Fire desk was checking and would advise.

My wait was short. The phone rang, I was ordered to report to the Fire desk with my war bag immediately, which I did. I was somewhat awe-struck to find that Major Kelley, the Regional Forester himself, had taken over the fire desk and was giving the orders. I did not know him well at the time but had a healthy respect for his reputation. He had commanded the "Forest Engineers," at Bellieu Wood in World War I. He was a lifetime Professional Forester and had been assigned to Region 1 to whip the Fire Problem.

All personnel were aware that the Major believed sincerely, that if a forest fire blew up, some ranger, forest supervisor or fire boss had failed. His solution was simple. Any one who failed was discharged, after a hearing of course. All fire control officers knew, therefore, that they must place any fire under their jurisdiction under control within the first burning period. If they did not do so they must be able to prove that control in the first burning period was beyond the realm of human capability, else wise, finis to a Forest Service career.

Naturally I listened to Major Kelley very carefully. I was to take charge of what they called the "Small fire" on the Selway named "Martin Creek". It was estimated at the time to be 35 miles in perimeter. Burning in severe mountain terrain at elevations ranging from 1,500 to 11,000 feet.

285 men were then on the fire, bossed by local woodsmen. No roads, no bull-dozers, all wilderness area, several days hike from the nearest roads. It was being supplied with an increasing number of pack strings from the nearest roads and the flying field at Moose Creek R.S. Manpower was being flown in whenever the bush pilots could see through the smoke.

Kelley advised that 5 fresh saddle horses had been arranged for me in relays, "Pony Express" fashion. He emphasized, "You can make it by daylight. Kill those horses but get to that fire and control it!" More manpower he promised when possible. When? No forecast. Reason? (1) Mostly too smokey to fly them in. (2) The Big Fire further down river where the need was greater. Manpower on it that day was 4,000 and 50 Forest Officers.

I rode all night, driving each of the horses in turn, at full gallop. A wild ride into the unknown.

Pitch dark. I held my hands and arms extended to protect myself from overhanging boughs.

Since I'd once been a buckaroo I was unseated only 2 or 3 times.

I made it by dawn and took charge. Then. — Several days of heart breaking labor. I wore out 5 horses and burned their feet, getting to, through, around, away from and back to the Martin Creek fire. I would chase it one day, and be chased the next. Kelley was marvelously faithful, sending a few men, till on Pete King I had 985. We had luck, good and bad. The fire burned one 150-man camp with all its supplies including two string loads of fresh beef. The fire barbecued the beef but we ate it later anyway! A wild rumor went out that we had burned up 77 men that day! Headlines in the Spokesman Review said. But it was false. The rumor occurred because the cook had stayed at the camp till the fire hit it, then losing his nerve, he ran all the way down the Selway river without stopping, till he reached civilization! But we did control the Martin Creek fire. On that day of control its perimeter was 51-1/2 miles. The Little Fire!

The day after we had controlled Martin Creek, I was inspecting the fire line and looked west around noon. In the distance I could see a huge smoke cloud boiling up. It was as great as the clouds which now result from the atomic bomb! Also an ominous roar, as of a thousand electric sub-stations, convinced me that the Big Fire "Pete King" had blown up and a huge fire storm was headed our way.

We had seven camps on Martin Creek Fire that day. Six had telephone or radio, one had no communication. I pushed my horse to the latter camp and met my assistant Fire Chief Gallagher there. "What are you doing here?" he joshed, "Don't you see that Big fire coming, all the guys at the Big ranger station will want to talk to you." "Yeah," I said, "I see it, I hear it, that's why I'm here. I must get some sleep as must you or we'll be useless tomorrow. Get some sleep, we'll have a message from Kelley by daylight."

At daylight this message came from Kelley: - "Tell Ranger Williams the situation is desperate. Tell him to take every man he can spare from the Martin Creek fire and get up there on Moose ridge if he thinks he has time and see what he can do to stop the Pete King Fire. Tell him to BACKFIRE. With a line if he can. Without a line if he thinks he must. Anything else he thinks he can do, tell him to try. If it does not work out I will not hold it against him."

"Wide open orders, what now?" asked Gallagher. "Holiday for all hands except you and me Chuck," I replied. "We'll go up and reconnoiter. If we tried throwing men up there into the path of that fire storm without knowing our ground, all we'd do is burn them up." We started for Moose Ridge on horseback and were halfway there when the fire topped Moose Ridge. The sight was eerie and terrifying. Whole trees 3 and 4 feet in diameter and 150 feet long were shrieking, moaning, groaning and floating crazily through the air 4 and 5 miles ahead of the main fire. We retreated to Wylies Knob, a peak 11,000 feet high with a rock thumb 200 feet tall on top on which was bolted a lookout house. We studied the scene from there. At that point the dying Martin Creek fire had blocked the Pete King fire for a swath 16 air miles wide. However, it was still galloping past, slowed slightly by huge Moose Ridge, but burning unchecked for another swath 10 or 12 miles wide. If not stopped in the next 24 hours, given 48 it would be deep in Montana. It had made 25 airline miles across many canyons the first afternoon.

We talked with Ranger Case at Moose Creek R.S. George would have been on the line himself but he had a broken leg in a cast. He had a plan. Briefly: Back up to the Rattlesnake bar-Shearers Peak ridge which extends from the Selway river southerly to Shearer's Peak and the Martin Creek Fire. This was about 12 miles ahead of the main fire. If we could fire out downhill that night; by next a.m. we could make our backfire run up Bitch Creek. Thus temporarily change the wind direction and hold the Pete King fire at the Selway River. Meantime Case promised to shuffle in as many more men as could be flown in the time available.

The plan went into action. 900 or so men were used. That evening, first firing narrow strips a few feet wide; then burning increasingly wider strips as it became safe. By 10:00 a.m. next day, which is blow-up time, back fires were being set a half mile wide. Then suddenly the entire backfire began running up the Bitch Creek canyon with increasing speed due to the suction of the onrushing Pete King fire. At 11:00 a.m. the two fires met in one boom. The backfire's drive had become great enough to halt Pete King. The whole trees that had been flying ahead of the Pete King fire were blown straight up in the air where they cooled and fell harmlessly. Not a single spark got over our lines!

Next day we had to backfire Magpie Creek as the Pete King fire was raging down it. About 6,000 acres had to be fired out in a manner to change the wind direction. Halfway up Magpie Creek was an old burn where crisscrossed windfalls lay 4 and 5 deep. If we could fire that first, then drop back to the canyon's mouth at the rivers edge; the heat from the first backfire would pull the second to it and control the sparks. I picked 7 men for the job. All fire bosses. Bill Boyd in charge on the east side of the canyon. Myself with assistant Chief Gallagher and the Swede Fire boss Waldron took the west side. We were sticking our necks out, I explained to Chuck and Bert as we hiked up the canyon. We wanted it to burn, but we had to get our backfire going first or we couldn't control the draft. Meantime our Bitch Creek backfire might crawl down the hill behind us before we got back. If it did we'd be trapped! Risky: But we had to chance it.

We went on up the canyon and touched off the backfire in the old burn about 5 miles wide and it went roaring up the mountain. About 9:00 a.m. I saw smoke puffing occasionally down Magpie Creek behind us. Worried, I sent Waldron back to see if the fire there had burned across Magpie Creek behind us. "If it has," I said, "Rush back and warn us, as we'll have to get out of here." He left. Minutes later I saw more puffs of smoke. Alarmed. I called the other 6 men to come quickly. Busy, they paid little heed. Scared! I called them vile names and really bellowed! Surprised at my language they sheepishly hurried up toward me. One stopped to light a smoke. I hollered "Don't smoke, you might start a fire." They came on, laughing, as setting fires is all they had done that day. Arrived at my side they looked down the canyon. By that time the fire was racing at us a mile or so distant. Gallagher only, could speak. "Which fire is the coolest, which way will we run?" he asked. I replied, "I don't know, but head straight at the fire below. You take the lead. I'm afraid of a panic. If any of the men stampede, clobber them with your walking stick! There's a gorge back there which is only a few feet wide. It's all rock due to a slide some years back. There is nothing on the ground there to burn, if we can get there we'll follow the seam up to a rockslide above and be safe. I'll bring up the rear and if anyone tries to run back I'll clobber him!" Long before we got there the fire was racing through the treetops over our heads! My gait wobbled, I almost ran back myself, but managed to stagger ahead. We reached the gorge and staggered up the seam like squirrels up an eave spout. My thoughts. "This is it!" Well my insurance is paid, my family will be ok as they'll also get a small pension as this is line of duty! I wondered also what people would say of the ranger who burned himself and 6 others up in his own backfire! But we kept on. We made it to the rockslide. For a while we were breathless and speechless and thoroughly cowed! Then the 7 of us slapped each other on the back like maniacs and laughed hysterically. Finally we remembered Waldron. We thought he was a goner for sure. Minutes later we heard a crow like a rooster above us. There stood all 6 foot 4 of Waldron on a little cliff flapping his arms and crowing like a chanticleer! "Hey Bert," I hollered. "Hey Buck," bellowed Bert, "The fire's across the creek!" In a few moments he joined us. I asked him how he escaped. He replied in his slow Swedish drawl, "I vill tell you. You remember dose cliffs you call a precipice?" "Yeah," I said. "Vell I got on pun, and pen de fire singed my butt I went Yumping from precipice to pace-a-prec and back to prec-i-pice again and here I am!" Everyone roared. The mental picture of a 270-pound swede jumping from one cliff to another safely! Was quite a relief.

That night in camp. The cook had made some dough gods. They were rectangular in shape but black in color as the campfire was too hot. The Fiery Finn with the red beard was staring moodily at his plate, occasionally poking a finger at the dough god on his plate, his moustache drooped. "What's the matter Finn?" I asked. "Can't you eat?" "That ain't it," he said moodily. "I was just thinking, if you and the Swede hadn't been there today, we'd all look just like these doughnuts! But I still think you timed that one too d— in close." I flushed and stammered, "I—I—I— I didn't really think it would do that."

We continued to fight the fire all fall until it finally rained. All told my crews built and held 160 lineal miles of fire line on Pete King. How big was the fire? I don't know exactly. I flew it one day by airplane for 2 hours and didn't see it all. I always described it as being 75 miles long, 25 miles wide in the widest place, and 2 miles high since it burned from 900 ft. to 11,000 ft. elevation, about a half million acres. A wildfire.

|

|

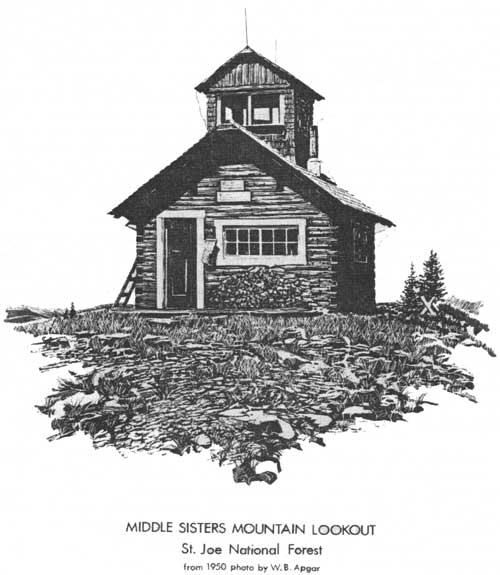

MIDDLE SISTERS MOUNTAIN LOOKOUT St. Joe National Forest from 1950 photo by W.B. Apgar |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/early_days/4/sec10.htm Last Updated: 15-Oct-2010 |