|

Early Days in the Forest Service Volume 4 |

|

A SMOKECHASER ON POT MOUNTAIN

By Robert G. Elliott

In 1924, I was about to graduate from a small high school in Northern Idaho and I badly needed a job for the summer so I could enter college in the fall. I had worked the three previous summers in the hay and harvest fields on Nez Perce Prairie but the pay was low and there were many days when one could not work because of rain, so the take-home pay at season's end was pretty small.

I talked to the principal of the high school about my problem and my desire to go to college. He was most sympathetic and also wanted me to continue my education. "Maybe I can help," he said. "How would you like to work in the United States Forest Service? The job pays $80 a month and food."

Eighty dollars a month and food. That meant that if I could get the job, I could bring home three month's wages or $240.00 at summer's end—a small fortune!

So, I filled out an application form and the professor attached a letter of recommendation to it and sent it to the Forest Service Supervisor, Paul A. Wohlen, at Orofino, Idaho.

I got the job! I took a train to Orofino, the Forest Service headquarters, with the clothes and personal effects I would need for the summer. The Forest Service put me up overnight in a hotel. My "room" was a cubicle no more than 8 feet long and 4 feet wide! The bathroom was way down the hall and was shared by about 40 Forest Service personnel.

Next morning, I trudged over to headquarters commissary with my duffel bag on my back and was told that I was to go out on the next truck. The truck was a Nash-quad, a four wheel drive rig; I, along with three other guys, rode in the back on top of all sorts of food and supplies for the Clearwater Headquarters—Bungalow Ranger Station.

After lurching and tearing around 60-some miles of hair-raising mountain road, we arrived at Pierce City, Idaho.

"Well, this is where you guys get off," the truck driver cheerfully announced. "The Oxford Meadows Ranger Station is down that muddy road 16 miles ahead. It's so muddy that a four wheel drive can't navigate it. It's only 16 miles, though, and you can easily get there by dinner time. However, a piece of advice—ask the Commissary Clerk for a Forest Service pack bag; put in just what you barely need, carry that much and leave the duffel bags for the pack train—he will deliver them in a few days to the Bungalow."

Off we go to Oxford Meadows: Sixteen miles doesn't seem to be very much but over a completely muddy and slippery road with a pack—even though small, for a kid just out of high school, it became quite a trip.

The Ranger Station, Oxford Meadows, at last. A beautiful, big log building with several wings; cook shack, bunkroom, and Ranger's quarters and office. A wonderful dinner—the Forest Service feeds its people splendidly—next morning a fine breakfast and then, pack on your back, we were off for the Bungalow.

This hike was only 12 miles. Also, it was downhill for the first 3 or 4 miles and then we were on the road alongside the Oro Grande River. It was pretty much water level but more importantly it was graded out of river sand and did not have the deep slippery mud of the day before.

The Bungalow at last. It had a separate bunkhouse—two stories, a Commissary, a cookhouse and mess hall, a barn, a blacksmith shop and numerous sleeping tents. It looked like a real city:

We checked in with the Ranger, Lester Van Arsdale, one of the fine guys I have met in a lifetime and he assigned us to the various tents. He told us that the "Wake-up" triangle would be rung by the cook at 6:30 a.m. each morning, the breakfast triangle at 7:15 a.m., and then we would be assigned to our job or crew for the day at 8:00 a.m.

My first day at work——Disaster:

I was awakened at about 8:15 a.m. by a hand on my shoulder—the hand of the Ranger. He said, "Look, youngster, you slept through the wake-up bell, the breakfast bell, and did not show up for assignment to work."

I guess the two days' hikes of 16 and 12 miles had really tired me out but anyway I had slept through all the bells and had not reported for work. I thought to myself—well, I start the long hike back, I really blew this one. In those days no one was guaranteed a job—you either produced or someone replaced you.

The Ranger, Lester Van Arsdale, was completely patient. He said, "Go get some breakfast and I'll put you to work." I said, "Mr. Van Arsdale, I don't need any breakfast, just tell me what you want me to do." He replied, "Nonsense, I'm not going to send you out with an empty stomach— go to the mess hall and get something to eat."

In the course of this brief conversation, I was completely dressed and off at a trot for the mess hall. The cook snarled, "What do you think this is, a short order house?" I replied, "I don't want anything to eat but the Ranger sent me over. He insisted I have something."

With very poor grace on the part of the cook, I was served a lot of food, not a bite of which I could eat. In less than 2 minutes I was out and trotted up to the Ranger.

"Do you know anything about tools?" "Sure, I have been a farm kid all of my life." "Well, that's what your application said—go to the Commissary tool house and get a mattock, an axe, a pick and a shovel." He took me about a half mile up the trail from the ranger station and showed me how he wanted the trail graded and cleaned. I was all by myself where most of the other kids were under the supervision of a foreman who could show and instruct them. Man, did I move dirt!

About 2 weeks later—Recognition and Triumph! We were all sitting at dinner in the mess hall when one of the pack-string pilots who packed to Canyon Ranger Station, down the trail which I had been digging, said, "Hey, what crew is digging on the trail above the swinging bridge—they're sure doing a fine job?" Ranger Les answered "That isn't a crew—it's Bob Elliott who is sitting just across the table from you—he's working all by himself."

The packer looked at me and asked, "Do you know that old badger stationed at Larson Creek?" Well, of course I didn't know the "old badger" so I just shook my head. "Well," the packer said, "that guy has the reputation of digging more trail than any other guy in the Clearwater Forest and you're doing twice as much." When I got up to leave the table, my shirt buttons would hardly hold my chest!!!

Two or three days later when I was really throwing dirt, the Ranger rode up on his horse. Only the Ranger was permitted a saddle animal (other than the packers, of course). Ranger Les's saddle mare was named Bonnie. She was a spirited animal and yet very gentle. She liked nothing better than to nuzzle all of us "trail monkeys" in exchange for a neck pat or an ear scratch.

Ranger Les rode up, smiled his charming grin and said "I guess you know by now why I put you to digging trail all by yourself, don't you?" "No, why?" "Well, when you slept through the wake up bell and breakfast bell on your first morning, I thought I might as well send you home. Then I thought, 'I'll give him a tryout.' Well, youngster, you have measured up, you like to work so now I'm giving you another assignment—the Telephone Crew. Fred Baldy has been watching you and he wants you on his telephone crew."

"Lord, Ranger Les, I don't know how to climb or anything about telephones." "I know that and so does Baldy, but he'll teach you and he wants you. You'll like the Telephone Crew much more than just digging trail all by yourself. You'll be in a crew of four and they are all good guys, hard and knowledgeable in their work and you'll enjoy it." "When do I start?" "As of this minute."

"Clean up the bank you have stripped down, pick up your tools and take them back to the commissary and try to learn something about telephone crews—how do you dig a pole hole in soft dirt?—how do you dig a hole in solid rock?—how does a split tree insulator work?—how do you tie it to a tree or a pole? The Assistant Ranger is there and so is the blacksmith and the tool Commissary man. They'll all help you for the rest of the day; and by tomorrow you won't be so ignorant about telephone work."

Wow! Here I was on the telephone crew my first summer in the Forest Service! How lucky could I get? We were an "elite" crew, only four of us to build and maintain telephone lines and telephones in the whole Ranger District! Most of the other sixty-odd guys were digging trail or cutting trees—but we were telephone men—all except me, of course, who didn't know anything about telephones!!!

I could hardly wait for Fred Baldy and his crew to come in that night! When they got in, I went out in the packer's yard to meet them and before I could say a word, Mr. Baldy came over to me with his hand out and said, "Bob, the Ranger rode by where we were working today and told me that I could make you part of the crew and that you had accepted. I'm very happy and I hope you are." "Happy, Mr. Baldy? I am tickled to death!" "The name is 'Fred'; not Mr. Baldy, ever."

"You and I and Les and Jack will be a closely knit unit which will do anything that is necessary to make this Bungalow District the best District in the whole Clearwater Forest!"

"Our basic work is to build telephone lines but we'll smokechase and fight fires when necessary. We'll repair trails when we see the need. We'll blast rocks and build bridges when necessary—we do everything. I want only people with me who can do lots of things and I asked for you."

This was the start of two very happy and productive summers under Fred's supervision. Supervision??? No—he worked as hard as any of his crew. Guidance would be a much better word: He was an inspirational guy. He might show up in our bunk tent at three o'clock in the morning in his underwear and say to us (his crew), "Look, there's a fire on Bald Mountain and they've assigned it to us—Let's Go!" We would go: Cheerfully and enthusiastically!

Two summers I spent on the telephone crew. Hard work, no doubt. Varied work, of course. Good companionship, the very best! We had an esprit de corp that never varied. The same crew for the two summers with Fred as the boss, and each of us thought the others were the best guys who ever came down the trail! At the end of the second summer when all of the outlying crews were called back to the Ranger Station to police it up for winter duty, Ranger Les hunted me down one day and said, "Hey youngster, how would you like to be on 'Pot' next summer?"

I darned near fainted: "Pot" was Pot Mountain, one of the highest peaks in northern Idaho. "My gosh, Les, do you mean it?" "Yep, I mean it, if you would like to do it." "You know Turk Oliver who has been in charge of Pot Mountain for several years? He and his partner didn't get along this summer and he has asked for you."

Again, "Wow!" This was the elitist of the elite! A lookout-smokechaser job. We didn't have too many peaks in the Clearwater Forest high enough to justify a two man crew and Pot was the most revered and wanted of all of them. The top mountain crews were truly looked up to by everyone in the whole forest. When I somewhat recovered from my amazement at my luck, I rushed to the telephone and called Turk.

"Do you really mean that you and I are going to be partners on Pot next year???" "Sure do, if you agree—I asked Les to send you up!" Agree?? Good, Lord, if I could have kissed him over the Forest Service telephone line, I would have.

Well, in a few days Turk was down at the Ranger Station, having winterized the lookout cabin on Pot Mountain, and we spent all of our nights planning for the next summer. We spent most of our days sharpening tools, oiling them and just generally getting things ready for winter and talking about "Next Summer on Pot!!"

Turk decided to enter the university that fall and my joy was unconfined. What a joy it was when the two of us would get together at night, forget the studies and quizzes of the next day, and just talk about "Next Summer on Pot!"

Well, next June came and I told my mother that after final exams I was just going to be lazy and loaf around for a few days before I went back to the woods. She thought it was a splendid idea and seconded it immediately. On the first day of my loafing period, I told mother to lay out my stuff, that I was leaving for the Forest the next day. She just smiled and started getting out the clothes I would need.

When I arrived at the Bungalow Ranger Station three days later—after a train ride, a four-wheel truck ride and two days' hike—Turk was already there. Instantly, we were full of plans—When do we get to Pot? Turk got the latest report. "Well, Ranger Les asked a guy going to Chamberlain Meadows a day or two ago to look at the trail up the side of Pot, and the guy called and said that it was still covered with snow and ice and would be impossible to negotiate with pack mules to bring us our grub. We'll have to wait a few days." A day or two later, Ranger Les caught the two of us together.

"O.K., I've noticed the two of you following me and looking at me, so why don't you start for Pot tomorrow?" I'll tell you what I want you to do. Take enough grub to last you for a few days, some telephone tree climbing hooks, insulators and tools and start toward Pot, fixing up the telephone line as you go. Lord knows, Bob, that you should know something about telephone service after having worked with Fred Baldy for two summers. When you get to Elk Camp, call in and tell me how the trail on up to the top of Pot is. (Elk Camp was about four miles below the top of Pot.) When the trail up the side of the mountain is in good enough shape for two or three mules to negotiate, let me know and I'll send up the packer with your grub and the rest of your stuff. Don't give me any funny reports before the ice is gone from that trail because if a mule rolls and breaks his neck, just remember that I think more of him than I do of either of you."

About a week later Turk and I were at our summer home—the top of Pot Mountain—7,500 feet above sea level. We could see all of northern Idaho and on clear days a lot of western Montana and some of eastern Washington. An inspiring sight!

When we arrived at the lookout, we arranged our grub and policed up the place. The lookout cabin was 12 feet by 12 feet in size. It contained two army bunks, one stacked on top of the other, a sheet-iron "sheepherder's" stove and a small table just big enough for two to sit at and eat.

The cabin was constructed of whipsawed lumber. If you have never seen whipsawed lumber, you have a new experience coming. To whipsaw lumber you carefully cut a tree so that it will not completely fall. Instead, it will lean against another tree. Then two men take a whipsaw and start to work. The whipsaw is like a cross-cut saw except it is longer—ten to twelve feet long and all of the teeth are slanted or hooked one way. One man gets on top of the log and pulls the saw up. The other man on the lower side pulls the hooked teeth down and does the cutting.

A whipsawed board is something fearful and wonderful to behold, depending upon the skill of the two men who did the sawing. It may be anywhere from six inches to eighteen inches wide and its thickness may be two inches on one side and one-quarter inch on the other side.

Nonetheless, our lookout cabin on Pot was constructed of whipsawed lumber and did make an enclosure of sorts. There were plenty of cracks through which mice, chipmunks, rock squirrels, birds and occasionally rats could, and did, enter. All four sides had glass windows—carefully brought up the mountain with one small window sash on each side of a pack mule. On top of the cabin we had a map board platform (reached by means of a board ladder) which we used to spot fires or "smokes".

When we got the place policed up and our grub arranged, Turk said, "O. K., now let's decide who does what about the daily chores—can you cook?" "If I have to, to sustain life, I can, but it's horrible to have to eat." "Well, I can cook and I like to", Turk answered. "If you will carry the water from the spring down the mountain side, I'll do all the cooking." "Agreed", I said.

The spring was down the side of the mountain about 3/4 mile and the way to bring the water up was on your back with one of two water pack bags, one which held five gallons and the other ten. Needless to say, coming back from the spring was all uphill since the cabin was on the very top of the mountain. Carrying the water was a rough job but I never made a better bargain!

This guy, Turk, was a superb cook! He made homemade yeast rising bread as well as mother ever made it; pies, cakes, cookies, candies, casseroles, and everything that could be made with our limited larder.

After meals, we would play "Pedro" with our worn deck of cards to see who had to wash the dishes. We would start out with a declaration of—best two out of three—then we would agree to the best three out of five, four out of seven, etc., etc. Sometimes we did not determine who was to wash the breakfast dishes until it was time to get dinner!

Other days, we would target shoot to determine who had to do the dish patrol. Turk had a specially made 32-20 single action Colt pistol with a seven inch barrel and I had a 22 Colt Woodsman with a six inch barrel.

We used the 22 caliber for the most part because of the cost of the cartridges. We burned up more than 1,200 cartridges for the 22 that summer.

I thought I was a pretty good pistol shot, and I was. I proved it when I won two handgun matches at American Legion Turkey shoots that fall. I never, however, was a match for Turk with the handgun. He could shoot it just like pointing his finger. After the target matches, I generally washed the dishes so I tried to steer the competition to "Pedro"—sometimes I could win there.

When we started for "Pot", Ranger Les told us that he wanted us to level off the rock ridge south of the present cabin so a new lookout station could be built.

"You know, that old whipsawed cabin could fall down with the snows of any winter or the winds of any summer. I want you guys to build a new level foundation so that we can set up a new lookout station. I'll send up some dynamite, some caps and fuse so that you can blast off the rocky points and break up some more boulders to fill in the cracks. Before the summer is ended, I expect to see a level foundation at least fourteen feet square so that we can set a new cabin up there. Be sure and take some rock drills on the pack string and a single-jack hammer so you can drill blasting holes when you have to."

We worked at the foundation for the new cabin in desultory fashion for a lot of the summer days, but needless to say, it was not our most pleasant project. However, at the summer's end when Les rode up to see how we were doing, he was most complimentary on the progress we had made on the new foundation.

In this connection, I must mention that we dragged up some tremendous rocks to the top of that lookout ridge. We did it by means of a crudely constructed windlass and a couple of skinned tree skids! When Ranger Les looked at it he laughed and laughed, but then said, "It sure is a solid foundation and can certainly hold up a twelve by twelve cabin!"

Again, speaking of the new cabin, how do you build a new cabin unless you want to whipsaw more lumber? Well, we had a sawmill down at the Bungalow Ranger Station. This old crude mill could certainly saw lumber. That is in terms of two-by-fours, two-by sixes, two-by-eights or eight-by-tens, but one-by-fours was about its smallest dimension and I suspect that if anyone had ever asked the sawyer to turn out some tongue-and-groove, he would very quickly have had a peavey imbedded in his skull. The sawmill could, however, turn out beautiful white pine of limited dimensions suitable for cabin building.

How did we get the lumber to the top of a mountain for a lookout cabin? By mule back, of course. The mule was the universal freight facility once you left the wagon road! We would cut the two-by fours into six or eight foot lengths and then tie them into bundles. We would put one bundle on each side of a mule, pointing downward, with the upper ends crossed over the top of the mules back. Then we would rope it solidly to his packsaddle.

You had to know your mules. Some were inclined to panic when they saw that menacing cross of lumber just a foot or so behind their ears.

Panic? I'm afraid I do injustice to the mule family. A mule will take apparent fright if he has space to buck off the pack and make you laboriously load it on him again. But—if you start him up a trail where his bucking or plunging might cause him to roll over a cliff and break his own neck, then he will become surprising docile. A mule has a great sense of self-preservation. A horse is completely different. He will run and plunge until he kills himself if he takes fright at the look of a pack on his back. That is why mule pack strings are safer than those made up for horses.

Speaking of the idiosyncrasies of mules—we had one in the Forest named "Fudge". She was a big, strong, bay animal with a very tricky disposition. It was always great fun to have the youngest trail monkey recruit hold Fudge by the halter while she was being loaded with the two packs. She had a real uncanny sense of timing and just as the last rope knot on the two packs was about to be tied to her pack saddle, she would start to buck and run, throw off both packs, dragging the trail monkey with her by the halter.

I myself was victimized, not knowing Fudge. The two packs were bucked off and Fudge and I ended up knee deep in the edge of the Oro Grande River. The trick with Fudge, as they then showed me, was to take the halter rope and put a loop—a "hackamore" over her nose. It didn't have to be tight, just as long as it was there Fudge would be as docile as a kitten.

We had another mule named "Ginger". He was a small stocky animal of reddish roan color. His trick was that just as you were about to lay a 150-pound pack on his saddle, he would take a step away from you. Well, you would wrench your back and legs and try it again and Ginger would take another step away. With Ginger, when you got acquainted, you would slap his left front leg. He would obligingly lift the leg. Then you would put a rope tie around the knee to keep the leg bent and Ginger would stand and doze while you put on his two packs.

Well, back to Turk and the lookout. The mountain itself was an old volcanic crater on the north side - the highest point - where the cabin was located. From the cabin, located on the edge of the old crater, a ridge extended south for a mile or so, like a handle. The old-timers had a slightly more descriptive name for the Pot, but the early map makers cleaned it up.

The result of the peculiar geography of Pot Mountain was that we could see our own smokechaser area to the east, the west and the north, but there was a section of about thirty degrees at the southwest which was blocked by Pot's handle.

So our routine as "lookouts" was to get up about three in the morning, go up on the roof to the map board tower and carefully scan all the territory we could see from there—the heavy and slightly more humid air of nighttime would settle the haze and you could spot smokes much better just at daylight. Heaven help you, however, if you spotted a fog or cloud wisp in another's' territory and send him scurrying to it only to find it was just fog! Well, after the trip and the scanning on top of the lookout cabin, the next thing on the routine was to walk the mile or so out to the end of Pot's handle and look in that direction. Turk and I took turns in this early morning "get-up". The part I liked best about it was the trip out to the end of Pot's handle. There was a big rock which I would climb to do my "scanning". It had a nice flat top and after my looking duties were over, I would stretch out flat and sleep for an hour in the nice morning warm sunshine. An idyllic life? It sure was for the most part but remember we had responsibilities. We had the foundation to build which we did in unenthusiastic fashion.

We also had another duty charged to us—making a decent map of our smokechaser district. The panhandle of Idaho in the mountain section had never been mapped! The U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey was around the territory and doing their best but we had no accurate maps. The Ranger told us when we went up to the Mountain, "I expect you two guys to come in this fall with a pretty good smokechaser map of the District. Put your pack on your back and go as far as you can in three and one-half hours and then mark as well as you can where you are so we can begin to get some reasonable smokechaser districts."

We took turns on mapping trips. Now, when you leave the top of a mountain and everything is down, you can go a long way in three and a half hours. Coming back up is a different proposition. Our smokechaser packs weighed 38 pounds. They included the standard tools; a mattock, an axe, a shovel, a compass, and the things which fed the smokechaser and made him happy at night.

The food—three "Smokechaser Rations" each one good for one day. Each ration had a can of corned beef hash, a can of bacon, a bar of chocolate, two packages of hardtack and some dried rice, as I remember. Poorer provender I cannot ever conceive of! So we changed our "rations" to something which would give you energy and be a lot more tasty. We would mix up "bannock" flour which was just plain white flour with some baking power and salt stirred through it. We would put about four pounds of this dry mixture in a cloth sack. Then we would put about four pounds of dried beans in another sack, and then cut off a big hunk of the hard smoked bacon we were furnished and that was our smokechaser ration—not only for three days but for several more in case you got caught on a big fire that you couldn't leave.

Mail was the most precious thing; and shelled walnuts or candied fruits, which Turk loved to put into his pies and cakes were another. Also, flashlight batteries for our two-cell flashlight (the Forest Service did not furnish flashlights or batteries in those days and if you tried to have too many batteries, they very quickly became shelf-worn and dead). The flashlight was of great assistance around the cabin at night when a mouse or a trader rat would come into the cabin. You could throw the beam over the barrel and sights of the 22 caliber colt and the varmint would be blinded and "freeze" and could be dispatched with one shot into the whipsawed floor or wall.

Well, as to the "river trip"—it was eight miles down to the river from the top of Pot (at 7500 feet elevation) to the river (at about 2500 feet elevation). This made a round trip of sixteen miles and, unfortunately, the last eight miles were all up! But periodically one of us would make the river trip to pick up mail and other "goodies" which we had the commissary ranger order for us from the stores in Orofino. These trips had a plus value—we would always take along a piece of fish line and a big feathered fly hook and catch a few trout from the river for a change of diet!!

Talking about the smoke and haze and the lack of visibility—we mad a fire on Skull Creek that year that covered 15,000 acres before the Lord mercifully gave us three days of gentle rain which permitted the firefighters to get it under control. It was not in our district but we could look directly down into it at night when the dew would settle the smoke and it was an awesome sight. Perhaps 1 to 2 miles wide and extending up Skull Creek for ten or so miles and all ablaze. It was a scary sight!

Before the rain put the fire under control, the Forest Service had more than 700 men fighting it.

These men were all transported in from Orofino first by four wheel drive trucks to the Bungalow Ranger Station and then by hiking for thirty-some miles to get to the fire.

All supplies, of course, were taken from the Bungalow Ranger Station by mule pack-train and if you don't think that was a logistics problem, you have never seen one!

Our job on Pot during the Skull Creek fire was to watch at night and look for spot fires ahead of the main fire and report them to the fire team captains. In a big fire like Skull Creek, the heat and draft of the fire will carry burning limbs for a half to one mile ahead and set another one! We watched for spot fires ahead each night and reported them.

The first part of our summer on Pot was fairly quiet. We patrolled, mapped, built the new foundation and had a few small lightning fires of no consequence in our own smokechaser district. We took turns going to the few small fires that we had in the district.

One sunny, hot afternoon, Turk and I were both sitting on the shady side of the lookout with our shoes off with not a care in the world. All at once, the sun went behind a cloud and almost simultaneously there was a peal of thunder! We both ran around the cabin and looked to where the sun should have been! There was a small, very black cloud and directly below it a big smoke where the lightning had struck! It was about four miles away as the crow flies but across a deep canyon from the lookout. I hurriedly pulled on my caulked logger boots since it was my turn to go to the fire—Turk had taken care of the last one.

By the time I had laced up my boots and picked up my smokechaser pack, the cloud had enveloped the whole mountain and the adjacent basins on the north and the south and it was raining torrents (rain mixed with hail). However, I had a fix on the fire so I started out! I was just outside of the lookout when another bolt hit. This one was about one-quarter of a mile away and it struck a small, stunted sugar pine. I was walking past one of the guy cables we used to keep the cabin from falling over the cliff. When this bolt came down, the lines of force cut across this cable and it made an explosion fully as loud as Turk's 32-30!

I jumped about four feet and went on. I was about 100 yards from the cabin and another bolt came. I couldn't see anything but a blinding flash but I could certainly smell the ozone! The lightning had burned all of the oxygen out of the air. Turk told me later: "I'll swear that that flash forked right over where you were and splattered all over the rocks on each side of you!—I was most happy to see you still walking after the flash!"

Since the top of the mountain was above "timberline" there was very little to burn—only a few sparsely scattered sugar pines and some mountain ground heather so strikes on top of the mountain were of no bother.

The cabin, although it was on the highest point of the mountain, was guyed by five one-half inch braided steel cables, all of which were solidly grounded and bonded to a ring of steel wire completely surrounding the map board on the roof of the cabin so the danger of a strike on the cabin itself was very small.

Well, I plodded on. I wanted to reach the fire, which was burning because the strike had come somewhat below the top of the ridge some miles away but in heavy and valuable timber. The strikes on top of the mountain were just incidental annoyances and of no danger unless one of them hit you.

To get to my fire, the quickest way was to go out Pot's handle and then cut down a ridge into the heavy timber where the fire was. I went, and when I got to where the fire was supposed to be in about one and a half hours, I couldn't find any fire! Smokechasers of my time will remember— how do you find a fre in heavy timber? Your visibility is only as the trees will let you see. Sometimes this is a few hundreds of yards and sometimes it is a few yards. Many times your nose is the best guide; you can follow the smell of smoke and finally find the blaze. However, if you are upwind from the smoke, your nose is no good either.

I looked for a long time but I could find no fire. Well, I said to myself, there was enough rain with the lightning to put out the fire, but—I had better get back to the lookout to see if some other fires were set by this storm—I had heard thunder rolling all the time I was hurrying to my supposed fire and all the time I was looking for it.

By the time I got back to the lookout, it was just about dark. Turk had spotted four more fires and had gone to what he thought was the most dangerous one. He left me a note telling me which fire he had gone to.

I picked up the phone to call the Ranger Station and the phone was dead. However, I soon remedied that because it was just lightning burns on the carbon protectors and scraping them with my pocketknife made the line alive again.

I rang up the Ranger Station and told them that I was back to the lookout and was going to another fre and they told me that I didn't know from nothing we had seven fires on our smokechaser district. I talked to Ranger Les about where the other lookouts had spotted them and agreed with Les as to which one might be the most dangerous and said, "I'll head for that one." Well, heading for "that one" was not as simple as it might appear—it was by now completely dark and getting from here to there was a bit of a problem. Unfortunately, lightning rarely strikes and sets fires right by a trail—it generally strikes as far from a trail as possible, just to add to the smokechaser's woes.

So I got out my light so that I can see a little something about where I am going. My light—what is that? It was a "Palouser" pronounced like Palooser—and consisted of a three to fve pound empty lard can, scrubbed and polished. To make a Palouser, you turn the can on its side, put a piece of wire from bottom to top for a handle, then in the opposite side with a sharp knife, or can-opener, cut a hole and shove in a long candle for a few inches of its length. The jagged edges of the cut in the lower side would hold the candle and when you lighted it, the polished interior would reflect some light forward—and it would not blow out. It was not a bad light.

So, with the light of the Palouser and my pack on my back, I took off for the fire which might do the most damage—at about 10:00 p.m.

When I got to that one, it had about burned itself out. A little trenching on the ground and not too many shovels of dirt soon had it under control. I went to another one, which had been reported, and luckily it also wasn't much of a fire so I had it whipped promptly. I went to the third one and it was a horse of a different color! It was burning about one-half acre.

The lightning strike had split (as it often does) and had set seven old dead hemlock snags on fire. You may say, well, so what—a bunch of dead hemlock snags on fire. The object was to save the young growth around the dead trees.

In an old burn, the seeds and cones on the ground will re-seed themselves about one time but if the little trees are burned and killed one more time, the forest itself may be dead and no more trees. So the idea was to contain the fire and protect the new growth. On this one, my work was certainly cut out for me.

Seven dried trees on fires and pieces of them flying hundreds of feet away to start new "spot" fires. I trenched as best I could to stop the fire from spreading on the ground and then I patrolled around and around the fire to put out the spot fires. There was no sleep that night. Nor much the next. Or the next.

When you get to a fire the objective is to put it OUT! If you don't, it may burn up the whole forest and yourself with it.

The immediate object is to corral or trench it so it cannot spread on the ground through the pine needles and "duff" as we used to call it. Then the next thing is to fall the snags or trees, which are burning in the tops or toward the tops. Then you have yourself a nice big bonfire of who knows how many acres but it is on the ground and you can shovel dirt on the hot spots to keep it from burning too fiercely or throwing burning limbs or bark outside of your trench.

When I arrived at my fire, I trenched madly for several hours to stop the ground fire and then I surveyed what I had to do—seven old dead hemlock snags from one foot in diameter to more than three feet—and I had to cut them all down with my axe so that they wouldn't throw other burning brands outside of my trench.

Did you ever try to cut down a burning tree with an axe? The first blow you strike with the axe will vibrate the tree and down from the top will come all sorts of burning limbs, knots, bark, etc. What you do is hit a lick with the axe and then jump. As you work on the chopping for a while you get less burning debris from the top because it has mostly been jarred loose. Then, if you have cleared away the fire from the base of the tree, you can work in some kind of comfort.

I worked as many hours as I could stand up—then I would curl up in my blanket for an hour and rest, then get up and start working again.

On the fourth day of my battle on this fire, I heard something—looked up and there was my partner, Turk, with a big grin on his face but looking about as tired as I felt. He said, "Well, looks as if you got this one about licked. I put out the little ones and then called the Ranger Station to find out where you were. We have one more a couple of miles but it's on top of a rocky ridge where there isn't much to burn. Let's the two of us make this one safe and then we'll both go to the last one".

We worked for several hours taking care of the fire and then lay down for a few hours of rest. Next morning, we were off for the "last one". When we got to it, Turk's judgment had been right and the fire was going out by itself—very little fuel having been available. We made short work of this last one and then started back for the lookout. The cabin was only about five miles away but unfortunately all of the five miles were up. We were extremely tired and somewhat hungry as well. The last we had to eat was the night before when we had cleaned up the last of my beans, which had been simmering in the edge of the fire.

We called in from Elk Camp, which was just a smokechaser locker with a "bear proof" cast iron tree mounted telephone to tell the ranger that we had all the fires out and were headed back to the cabin. Both of us could normally walk at a rate of three to four miles per hour but tired and hungry as we were, and going up the mountain, I suspect our pace was between one half and one mile per hour.

About half way home up the mountain Turk said, "Shh." There was an old rooster grouse walking across the trail. Turk made a beautiful headshot and we had meat. I said to Turk, "I'll pick him, clean him but how do we cook him?" Turk said, "I haven't been able to wash out my frying pan from my last bacon a couple of days ago because of no water, so it still has bacon grease in it; and, besides that, I have some bannock flour left—start picking!"

Pretty soon we had fried grouse and bannock biscuit right in the trail and no meal ever tasted better. The old rooster was as tough as his years deserved, but man, was he good. When we finished this magnificent repast, Turk said, "I'm awful tired, let's lay down for an hour or so." We both lay down on the mountain heather and went sound asleep for about two hours.

When we finally dragged into the lookout cabin, it was almost dark—it had taken us most all day to make about five miles. Turk said, "I have an idea for dinner." "What?" I asked. "A big coffee pot full of cocoa." "Great."

So Turk made up the coffee pot with condensed milk, cocoa and sugar and both of us went to bed.

About 16 hours later, somebody moved and the next day started—somewhat late, but at least we were up and we were rested. We made out the necessary fire reports the next day or so and went back to our regular routine.

The only complaint we got from the Ranger was a telephone call when he said, "I didn't send you two guys any help because I know you are both able and competent and you would call in if you figured you had something that you couldn't handle. Now get back to working on that foundation. You have a pretty soft life up there—Ha, Ha."

The summer went on for about two weeks and Turk and I worked on the foundation in our usual lackadaisical fashion, patrolled the "handle of Pot" and just assumed the usual routine life.

One afternoon in bright sunlight, Turk looked up from the foundation rock we were wrestling and said, "My Lord, do you see what I see?" Across the canyon in the same spot I had gone to about two weeks before and failed to find a fire, there was a h—lluva smoke!

It was a "hangover"—the kind of a fire that is almost extinguished by the rain accompanying the lightning—but isn't quite put out and which flares up later as the trees and the duff dries out. It is the most dangerous kind of a lightning fire because by then everything will be completely dried out and it can spread rapidly.

I said, "Well, it was mine and I missed it before, so I'll get it this time." I had no trouble finding it this time because there was plenty of smoke. It had burned on the ground to cover about an acre and was in the tops of a few trees.

Again, trenching in front of the spots of ground fire to prevent spreading, I threw dirt on the bases of more of the trees which I thought the fire might climb and then started to work on chopping down the trees which were on fire in the tree tops. This time the fire was in green, valuable timber and it was most important that it didn't spread. Green timber, however, has the important advantage in fire fighting over dead snags—the green trees are much easier to chop down.

After working the rest of the afternoon and all night, I had the blaze under control so it could not spread. Then, the only problem was to put it out!!! I worked for days on that stubborn fire—days and nights. Trenching, shoveling dirt and chopping down trees and brush.

I scouted around the ridge and found a small water seepage about one quarter of a mile away, from which I could fill my canteen and cooking pan. After I had scooped out a hole in the ground I had water.

When I became so tired that one foot would not lift in front of the other, I would lay down and rest for an hour or two. This was always at night when the natural dew would slow down the burning process and this was also the time I burned up another army blanket, unconsciously rolling toward more warmth.

About sunset of the fourth day, I heard something coming through the brush, which I thought was probably a deer or an elk and stopped shoveling dirt to watch. Here again was my partner, Turk, with that big grin on his face. "You've been gone so long that Ranger Les and I agreed that I had better come over and see how you were doing. I was sure you were doing Okay because the smoke had practically disappeared, but being awkward like you are, you could have fallen on your axe." Boy, was I glad to see him.

"I have a pot of beans cooking over in that hot coals spot", I said "and some bannock flour left and if you will mix up a biscuit, we'll have something to eat". Turk replied, "I brought lots of grub because I figured that you must be just about out. I can fix us a good meal, but I won't eat with you until you wash your face. You must have found water not too far away or you couldn't be boiling beans, so go to it and wash. You are about the filthiest specimen I have ever seen."

My trips to the water hole had for four days been pretty hurried; and just to get water, not to improve my appearance. So I guess I did look pretty bad. I wobbled around the mountainside to my water hole, stripped to the waist and really had a wash.

When I got back to the almost-out fire, Turk had some things that he had brought with him, cooking that simply smelled like ambrosia after four days of bacon, boiled beans and bannock biscuit. He said, "Let's eat. You sleep and tomorrow we'll both put out the rest of the coals". Next night we went back to the lookout and there was never a more comfortable bed than that steel army cot.

This was the last fire we had on our smokechaser district that summer.

A few weeks later, in late August, we had a gentle rain with no lightning, that lasted about three days. It completely soaked the forest and made it pretty safe inasmuch as the lightning season was about over.

Ranger Les called up and said, "Bob, I think it is safe to leave the lookout and Turk will button it up for the winter. I want you to go down to Larson Creek and help Roy Whitmore to close up his station. Get your personal stuff together and take off for Larson Creek in the next day or two."

Larson Creek was not only a smokechaser station, it was also an overnight station for the pack trains which supplied Canyon Ranger District and it thereby had a lot more supplies than just a lookout like Pot. The winterizing of a combined station such as Larson Creek was much more of ajob than winterizing Pot....

So, in a couple of days I was off for Larson Creek. It was a distance of about 15 miles by ridge-top through the trees but with no trails. You just went the easiest way. However, it was all down hill.

When I got within a few miles of the river, I began to find some real well worn trails—not as the Forest Service would have made them, but as the deer and the elk had made them. Then I remembered—the "Larson Creek Elk Lick!" It was famous throughout the Clearwater Forest as the place where the elk went to lick the salty water seeping over a big rock bluff.

When I approached a little closer I went more carefully and with as little noise as possible. I heard the bugling whistle of a bull elk or two and then I knew I was real close to the lick. It was no trouble to find it because all the trails down the ridge were converging on a small valley. It was an unusual sight when I finally arrived at the lick.

There was a granite rock ledge about 100 feet high, almost vertical. The granite ledge was perhaps 200 feet wide. Over the entire surface was a fine film of water seeping down the face.

All around the small valley, the fallen and half-fallen trees were rubbed bare of bark and actually polished by the visiting elk scratching themselves. It smelled like nothing as much as the cattle yard on the ranch at home.

As I sneaked up to the lick I counted thirteen elk. Some were licking the rock, some were lying down like cattle, and others were rubbing the trees to soothe whatever irritations they had.

I watched fascinated for several minutes and then a movement of mine caught the attention of a bull elk. He let out a piercing bugle and they all left—clumsily but, nonetheless, rapidly.

So on down to Larson Creek. I arrived there in mid-afternoon and Roy knew I was coming. He said, "The ranger told me you would be down today. I have a treat before I cook supper."

Where upon he brought out a crockery jug of homemade wine. He said, "I've been practicing all summer long, and this is my best product—I make it from the dried and canned fruit the Forest Station furnishes us, plus the sugar and a cake of yeast and, now in the fall, some huckleberries."

It was delicious and powerful.

We worked around the station for a couple of days and reported in to the Ranger Station. The boss said, "Okay, come in and fall any snags which are over-hanging the trail and fix up the telephone line as you come."

Next morning we got ready to head for the Bungalow. Roy had several jugs of his "Best Product" and he said, "I know that if I leave it here, these winter game ranger surveyors will drink it all up. I'm going to be back here next summer so let's take it out into the woods and bury it." We did just that, all except one jug, which I suggested we take along with us.

We planned to take two days to go into the Ranger Station, some 17 miles away since we were working on the way. We started early in the morning and worked all day long, falling snags and bolstering up the telephone lines.

About sundown, we arrived at Cave Creek Camp, another pack train camp where we were going to spend the night. Roy said, "I know you are famous throughout the whole forest as a guy who can't cook and I can, so you cut the wood and build the fire and I'll rustle up the grub." "Fine, but let's have a snort of your 'Best Product', first."

After about three snorts, I was really ready to cut the wood and build a fire. On about the third splitting stroke the handle of my axe caught on a bush and the reverse side of the axe went into my shoulder, clear to the bone. Roy patched it up as best he could, but said, "I'm damned if we are going to stay out here tonight while you bleed to death—we'll leave our packs and go on to the Ranger Station tonight so you can take the truck out to the doctor in the morning."

So, off we go for another 7 miles to get to the Ranger Station. Incidentally, we abandoned the remainder of the jug of the "Best Product."

Next morning after a miserable night, I boarded the four-wheel-drive truck for about a 98-mile drive to Orofino and the doctor. They did dignify me by letting me sit in the seat with the driver instead of the metal box behind, since I was an "accident case."

The Doc looked at my wound and said, "Well, this is going to hurt a little bit because it is all encrusted, I will have to swab it out and then stitch it up." Hurt a "little bit?" It did. The Doc said, "I won't let you go back for a few days to be sure that there is no infection."

After loafing around Orofino for two days, I called up Ranger Les and told him that if I came back, I could only work for a few days or so because University was about to start—anyway, I wouldn't be much of a worker. Les said, "Okay, youngster, I'll send your stuff out by tomorrow's truck and you go on back to school. I'll see you next year when you and Turk head for Pot Mountain."

So ended one of the most wonderful summers I had ever had and I suspect that any kid of my age could ever have.

I almost changed my course to "Forestry" so I could spend my life in the out-of-doors but since I had had two years of electrical engineering I decided to continue on Engineering and just to dream of "Pot", for next summer!

|

|

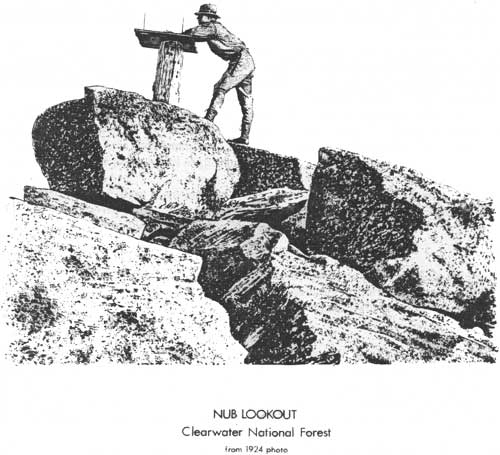

NUB LOOKOUT Clearwater National Forest from 1924 photo |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/early_days/4/sec7.htm Last Updated: 15-Oct-2010 |