|

The Flathead Story

|

|

Chapter XXI

BOB MARSHALL WILDERNESS

Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace established the 950,000-acre Bob Marshall Wilderness August 16, 1940. Extending into the Lewis and Clark and Flathead National Forests, the Bob Marshall Wilderness was created by combining and reclassifying three primitive areas: South Fork Primitive Area (established in 1931); Pentagon Primitive Area (established in 1933); and Sun River Primitive Area (established in 1934).

The Wilderness is named for Robert Marshall, explorer, forester, student of nature and a conservationist, dedicated to the development of effective and meaningful wilderness management policies. Marshall was familiar with and interested in the mountain country of western Montana. Trained as a forester, he served for some years at the Forest Service Experiment Station in Missoula. He used his energy, personal wealth, and organizational ability to establish the Wilderness Society in 1935.

Marshall died September 19, 1939, at the age of 38, less than a year before the first National Forest wilderness was established. At the time of his death, he was assistant to the chief of the Forest Service, responsible for recreation and lands activities. He devoted much of his energy and intelligence to the development of the National Forest wilderness system. Marshall said of wilderness:

"It is the song of the hermit thrush at twilight and the lapping of waves against the shoreline and the melody of the wind in the trees. It is the unique odor of balsams and of freshly turned humus and of mist rising from mountain meadows. It is the feel of spruce needles under foot and sunshine on your face and wind blowing through your hair. It is all of these at the same time, blended into a unity that can only be appreciated with leisure and which is ruined by artificiality."

Approximately three-fourths (710,000 acres) of the wilderness is in the Flathead National Forest. It extends 60 miles from north to south along the Continental Divide and includes the headwaters of the Flathead River on the west and the Sun River on the east. Elevation varies from 5,000-foot valley floors to more than 9,000 feet along the Continental Divide.

|

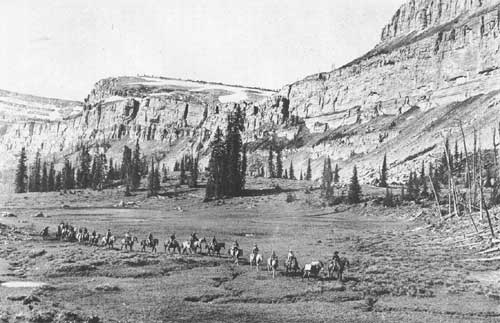

| Bob Marshall Wilderness. Chinese Wall at the head of Moose Creek. E. D. Swan took this picture in 1934. |

South Fork Primitive Area, established in 1931, contained 584,000 acres. It included the South Fork of the Flathead River, from above Meadow Creek, and some of the tributaries of the Spotted Bear River. Two 160-acre tracts of land had been homesteaded in the area in 1898 by Thomas Danaher and A. P. McCrea. Also, the Northern Pacific Railway owned 69,000 acres, acquired under the July 2, 1864, railway land grant. The remaining acreage was publicly owned. Under the provision of the General Exchange Act of 1922, the Forest Service acquired the private land holdings in 1935, 1940, and between 1950 and 1955.

No roads existed or were to be built in the South Fork Primitive Area. Improvements in the area were limited to trails, telephone lines, and other improvements necessary for administrative purposes. No private developments were permitted. Landing of private planes on the administrative airfields, except in emergencies, was prohibited. One area, at Murphy Flats, had been under special use permit to Joe Murphy of Ovando since 1922. Murphy abandoned the area; and the improvements were removed soon afterwards, when the lease expired. Campers were not permitted to stay longer than one week at any one camp in the primitive area.

Establishment of this primitive area received wide, general public support, voiced in particular by the late Howard Toole, a Missoula attorney. There was no organized resistance to establishment of the primitive area. Within the Forest Service, perhaps the most prominent figure in the establishment of this and the other primitive areas now contained in the Bob Marshall Wilderness was Meyer H. Wolff, Assistant Regional Forester for Recreation and Lands in Missoula. Wolff located the major boundaries on a map in his office.

Pentagon Primitive Area, established in 1933, contained 95,000 acres of public land, including the upper Middle Fork of the Flathead River and part of the Upper Spotted Bear River. The Forest Service imposed restrictions similar to those in the South Fork Primitive Area.

The Pentagon Area was separated from the South Fork Area by a nonprimitive strip of 31,000 acres of public land on the headwaters of the Spotted Bear River. This was not included in the original Pentagon Area because there was a possibility of waterpower development or a road connecting Spotted Bear with the road at Bench Mark on the Sun River.

This narrow strip of nonprimitive land along the upper reaches of the Spotted Bear River between the two primitive areas caused some controversy. Six years later, following considerable discussion, this strip was added to the Pentagon Primitive Area in 1939 with similar restrictions on development and use.

|

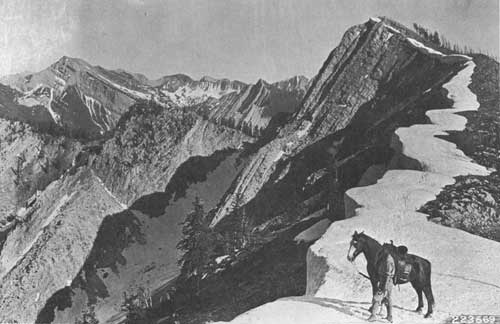

| Flathead Alps in the Bob Marshall Wilderness, at the head of the South Fork of the White River. Ranger in the picture is Henry Thol. The picture was taken in 1927. |

Sun River Primitive Area (240,000 acres) was established in 1934, east of the Continental Divide, joining the South Fork Primitive Area on the east and the Pentagon Primitive Area on the south. While the Sun River Primitive Area was entirely within the boundaries of the Lewis and Clark National Forest, the South Fork and Pentagon Primitive Areas were within the Flathead National Forest.

There was no private land, farming, mining, or other occupancy in the Sun River Primitive Area; there were some commercial cattle and horse grazing permits. The Bureau of Reclamation held an 18,000-acre reclamation withdrawal in connection with the Sun River project. This was later released. There was divided opinion among Forest Service personnel at first; eventually establishment of the primitive area was favored. Public sentiment remained divided. Those catering to tourists and hunters favored a primitive area, but some local groups preferred to keep the area open for grazing, summer home leases, and road building.

Restrictions quite similar to those imposed on the other primitive areas were to be applied in the Sun River Primitive Area. There were to be no commercial grazing permits, except for the grazing of the stock of outfitters, guides, dude ranchers, or others using the area for recreational purposes.

Any area of this size and nature does not lend itself to proper elk management and harvest, and problems are sure to present themselves. To properly understand the situations that are apt to develop, we must look back at the beginning of the buildup of the Sun River's elk herds.

Due to the laxity of enforcement or the nonexistence of game laws, the game population was at its lowest ebb at the beginning of the 20th century, not only in the West, but nationwide. At about this time, game law enforcement became effective. Then, in 1910, these areas were ravaged with many large forest fires; hundreds of thousands of acres were burned. Browse plants sprang up over most of these burned areas. As a result, the elk thrived and multiplied. By the late twenties and early thirties, there was not sufficient food on their winter range. Large numbers of elk died of malnutrition.

In the spring of 1933, a winter of deep snow and severe temperatures, 500 elk carcasses were counted in one 10-mile strip on the South Fork between White River and Cayuse Meadows. Graphically, the elk population curve reached the apex of the carrying capacity curve late in the 1920's. Then both curves started to descend, the carrying capacity falling much faster than the game population.

Today, they are both at a very low ebb. The carrying capacity of the range must be increased in order to provide more winter elk range.

Logging operations will increase the capacity of the winter game ranges in the Swan Valley and the lower South Fork, but the situation in the Wilderness is stagnated. During the 1920's, there were thousands of whitetail deer in this area. Because deer cannot compete with elk on an overcrowded winter range, the deer have almost passed out of the picture.

I spent seven winters in the South Fork during the 1930's on big-game studies. Following the decline of the great herd, it was easy to predict the outcome. Nature alone will not correct the situation, created by civilization driving these animals from their native prairies into the mountains.

Buffalo and antelope were also driven from their native prairies, but they are grass eaters and cannot survive for long periods on browse plants alone. Therefore, they did not become indigenous to the mountains like the elk and deer.

The Montana State Fish and Game Commission and the Forest Service did not stand idly by and watch the decline of this great elk herd. In 1936, the Spotted Bear Game Preserve was eliminated. Established in 1923, it encompassed 206,000 acres east of the South Fork, from the mouth of the Spotted Bear River to Cayuse Creek and extended to the Continental Divide on the east. The Forest Service also considered the possibility of reducing the elk herd by allowing hunters to fly into the administrative airfields on the South Fork on an emergency basis. To do this would have been in opposition to the Forest Service policy; but since this had not been publicly proclaimed for the South Fork area, it was a possible alternative. It was vigorously discussed; there was considerable divergency of opinion among Forest Service officials. The Montana Fish and Game Department favored opening the primitive area airfields and lengthening the 1937 hunting season to help reduce the herd. Groups, such as the Dude Ranchers Association, opposed use of the airfields.

On September 7, 1937, Bob Marshall, then Chief of the Division of Recreation and Lands in the Washington Office of the Forest Service, wrote Northern Regional Forester Evan W. Kelley opposing the use of airfields for public purposes: "(I) do not think the area should be opened to airplanes even with the rigid restrictions you propose. Precedent of opening a Primitive Area to commercial airplane entry will be very serious." The project was dropped September 8, 1937.

|

| Head of Lick Creek in Bob Marshall Wilderness. Photo taken in 1925 by Henry Thol. |

|

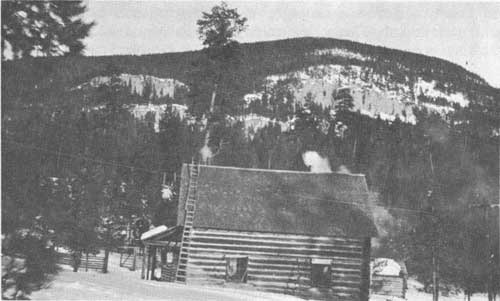

| Spotted Bear Ranger Station, built in 1906 by Ranger John Sullivan. This photo was taken in 1924 by Chance Beebe. |

In my opinion, the use of airplanes would have been of little significance in reducing the size of the herd. A few more elk would have been harvested; a few less would have starved. But it would not have saved the herd.

One thing that did help—or at least prolonged the decline—was the Montana Fish and Game Commission extending the regular hunting season in this area from 30 to 75 days. There is an extended season in this area today, although there is now only a fraction of the elk population that was there during the early 30's. Further attempts are being made to reduce the herd to a point below the current carrying capacity of the range and to hold at this low level until the range can recover.

The Sun River Game Reserve, in the Bob Marshall Wilderness, was established in 1911. It has little or no effect on the wintering of the elk herd as it is mostly on eastern slopes and does not provide critical winter range. It is an ideal calving area and summer range, but the herd leaves the area during an average bad winter. Summer range for game has never been a problem in this area.

Bob Marshall was a man of energy and dedication, trained in forestry. He was a great hiker, often going 60 to 70 miles in a day through rugged back country. Always interested in its preservation, he wrote at length on the importance of wilderness.

In the Scientific Monthly in 1931, Marshall wrote of wilderness as follows: ....."I shall use the word wilderness to denote a region which contains no permanent inhabitants, possesses no possibility of conveyance by any mechanical means and is sufficiently spacious that a person crossing it must have experience of sleeping out. The dominant attributes of such an area are: first, that it requires anyone who exists in it to depend exclusively on his own efforts for survival; second, that it preserves as nearly as possible the primitive environment. This means that all roads, power transportation, and settlement are barred, but trails and temporary shelters, which were common long before the advent of the white race, are entirely permissible.....

"A thorough study should forthwith be undertaken to determine the probable wilderness needs of the country. . . .Once the estimate is formulated, immediate steps should be taken to establish enough tracts to insure everyone who hungers for it a generous opportunity of enjoying wilderness isolation."

Marshall became Chief of the Division of Recreation and Lands for the Forest Service in 1937. He applied in practice his ideas of what a wilderness should be.

Reflecting public concern over the effectiveness of Regulation L-20 for primitive areas, Marshall developed Regulation U-1, U-2, and U-3 to supersede it. These new regulations defined Forest Service policy on wilderness and delineated area values and criteria. They were issued on September 19, 1939, 2 months before Bob Marshall's untimely death at the age of 38.

Primitive areas were to be reclassified to come under the U-l regulation. The three primitive areas (South Fork, Pentagon, and Sun River) met the requirements of the new U-1 regulation. The three were classified together under this regulation on August 16, 1940, and named in honor of Bob Marshall. In the U-1 classification document for the Bob Marshall Wilderness, it was stated:

"The L-20 conditions are adequate for U-1, no change in requirements; therefore, advertisement and 90 days notice to change to U-1 are not necessary Local public sentiment has staunchly supported establishment of Primitive Areas and no questions regarding change are expected."

In many instances the wilderness boundary does not follow any topographic feature. In some cases, the boundary is on a hillside, somewhere between the creek and the mountaintop, thus making it difficult to determine the location on the ground. Wilderness boundaries should be established definitely on the ground, just as the boundaries of private land, National Forest, or National Park boundaries. This is not the case in the boundary of the Bob Marshall Wilderness. This is something that will draw more attention in the near future as timber-cutting boundaries are established near the wilderness boundaries.

It is the policy of the Forest Service to refrain from violating the sanctity of the Bob Marshall Wilderness by its own people as well as the public. A few airplanes have landed on wilderness airports and one on Big Salmon Lake unlawfully. In each case, evidence was presented in court; and, in each instance, the courts have decided in favor of the Government, or the party pleaded guilty and was sentenced.

Homesteading on the Great Plains and railroad construction brought a local demand for lumber and railroad ties. In about 1886, Charles Biggs and others built a wagon road from what is now Hannah Gulch up Sun River to Gates Park. This is now about 14 miles inside the Bob Marshall Wilderness. They proceeded to cut railroad ties on Headquarters Creek and Biggs Creek and float them down the North Fork of the Sun River. Their main camp was on Headquarters Creek, not far from Gates Park. They cut 200,000 ties and hauled out 25,000 cords of fuelwood between 1886 and 1899. The operation was not economical due to insufficient water at times in Sun River and the long distance to market.

Construction of Gibson Dam on the Sun River above Hannah Gulch in 1929 inundated several miles of the lower end of this road. The 14 miles of road in the wilderness have now grown over; the logging scars have healed and most of the stumps are no longer in evidence. It is again a true wilderness. However, following the logging operations near Gates Park, a homestead claim was filed in 1911. It was never occupied. In 1913, four tracts of land in the Danaher Basin were homesteaded beside the Danaher and McCrea homesteads of 1898. They were filed but never occupied. Climatic conditions, together with the long winters and distance to market over a rough trail, made farming and stockraising in these areas uneconomical. There are no roads, private land, special uses or any commercial establishments in the Bob Marshall Wilderness Area today.

In the late 1940's and early 1950's, extensive exploration by gas and oil interests brought pressure on the Forest Service for leases in the wilderness. The Forest objected to this exploitation as incompatible with wilderness preservation. The Bureau of Land Management, Department of Interior (the granting agency), agreed with the Forest Service. As a result, no leases were ever granted in the wilderness.

In November 1949, a severe windstorm blew down a large volume of timber in the Flathead National Forest. Englemann spruce, being quite shallowly rooted, was especially vulnerable to a storm of this intensity. Fallen timber provides an opportunity for insects to breed and incubate, especially the spruce beetle. An epidemic of these insects struck most of the major drainages containing spruce, including Bunker Creek, just north and outside of the proclaimed boundary of the Bob Marshall Wilderness.

An on-the-ground survey in the fall of 1953 revealed that the spruce in the Bunker Creek area was heavily infested. To salvage the infested timber, the Forest Service announced plans to offer 23 million board feet of this timber for sale early in 1954. Harvesting plans called for a road up Bunker Creek, paralleling the wilderness boundary for about 5 miles. At the nearest point, the road would have been within about 1/4 mile of the wilderness boundary. A total of about 30 miles of road construction was required to complete the sale, control the beetles, and salvage this valuable timber. The road was to join the existing road at Spotted Bear.

Local opposition to this salvage program was aroused by an article in the Kalispell Daily Interlake. The article was written by a local outfitter and dude rancher whose interest, as well as the interest of other outfitters, would have been affected by the road development.

The Forest Service publicly explained its plans, including a presentation to the Flathead Lake Wildlife Association and other groups. The Wildlife Association, however, with support from outside groups, presented a petition against the timber salvage operation to the Secretary of Agriculture. The petition also asked that an area of some 279,000 acres of roadless National Forest land between the north boundary of the wilderness and near the south boundary of Glacier National Park, including the Bunker Creek drainage, be added to the wilderness.

In addition to the northern extension of the wilderness boundary, various groups wished to extend the south boundary of the Bob Marshall to include another 50,000 acres of roadless multiple-use area on the North Fork of the Blackfoot River. A memorial to Congress from the Montana legislature, asking for an extension of the wilderness, was unsuccessful. Not all people in high places were in sympathy with this memorial. The Governor of Montana failed to sign it.

Local people opposing the timber salvage plan were vocal and effective on this issue. Outside aid came in the form of letters to Washington from influential clients of local outfitters. The Montana Fish and Game Department also opposed the Bunker Creek plan and backed extension of the wilderness boundaries. Several groups, including the Rocky Mountain Sportsmen of Columbia Falls, the Kalispell Chamber of Commerce, the Flathead County Commissioners, and others were in favor of the Forest Service plan.

Although the road up Bunker Creek was viewed by some as violating the wilderness, it would not, in fact, have done so. Many people were of the opinion that a road was actually to be built into the wilderness and that wilderness timber would be removed. This was not the case. There was much infested timber inside the wilderness at various locations, but the Forest Service had no plans at any time to remove any of it.

This illustrates the need for a definite wilderness boundary that can be identified on the ground. In this particular case, the boundary is somewhere south of Bunker Creek; it does not follow the creek, but is along the toe of the slope in this rather wide valley. The road in question was to be back away from the creek, on the north side. Wilderness boundaries should be definite and treated as such. Logging or other commercial activities should be to this boundary, just as if the wilderness were private land or a National Park.

Because of road building costs and because much of the timber was already dead and would "check" before it could be removed, the Forest Service made an economic analysis and concluded that the operation was not feasible without appropriated road funds. Late in 1954, the insect epidemic having passed its peak, the salvage program and road plans were dropped. It is estimated that 20 million board feet of timber was lost. It is now planned to build a road up Bunker Creek and harvest the remaining timber in the near future.

The wilderness boundaries were not extended as petitioned. The Forest Service did assign a Regional committee to study the wilderness boundaries with particular reference to the proposed extension sections. The committee proposed some boundary adjustments in the Bunker Creek, Spotted Bear River, and Middle Fork areas. After considerable discussion, the Secretary of Agriculture rejected any boundary change, partly due to possible complications with the Bureau of Reclamation's proposed Spruce Park Dam project.

Controversies of this nature between the Government and the local public have occurred in the Flathead before. As an example, the following excerpt was taken from "Through the Years in Glacier National Park" by Donald H. Robinson, published in May 1960.

"It is interesting to note the opposition to the bill to establish the Park. Grazing and lumber interests, the ones who would seem most likely to object, showed little interest in it. Mining activity had almost completely died out, so there was little objection there. But certain local groups, mainly from Kalispell, cried out loud and long that it was a scheme of the Great Northern Railway to prevent other roads from entering the region. The truth of the matter was that the late Louis W. Hill, Sr., then president of the Great Northern, was foremost among the sponsors of the bill, hoping with Senator Carter, Congressman Pray, George Bird Grinnell, and others to create a public recreational area for Montana which would attract tourists and, subsequently, a source of passenger traffic and income dollars for the state. Opposition came from legislators who contended that it was not the function of the government to dabble in recreation.

"After passage of the bill seemed certain, the opposition interests began to backtrack and explain their reason for it. The following excerpt from an editorial in the Kalispell Daily Interlake attempted to clarify their stand on the matter: 'The establishment of the Park is not a calamity. The original opposition was due mainly to personal interests, such as a loss of hunting grounds, locking up of the area, no settling on the North Fork, etc.'"

The people of the Flathead have accepted Glacier National Park wholeheartedly today and point with pride to its natural beauty and proclaim the Flathead Valley as the Gateway to Glacier National Park, seemingly having forgotten that they tried to block its creation.

The geologic aspects of the Bob Marshall Wilderness are certainly worthy of mention and should be reviewed. There are a few known locations where trilobites can be found. The one best known was found in 1929 by Dr. Charles Deiss, formerly Associate Professor, Department of Geology, Montana State University. It is on the Continental Divide at the head of Open Creek and Basin Creek, just east of Kevan Mountain. The trilobites were animals whose bodies were divided longitudinally into three lobes. They belonged to the class of Crustacean of which crabs and lobsters are living representatives. They are from very small up to about 2 inches in length. Found in rocks from the Paleozoic era, they lived from 300 to 500 million years ago. They are the oldest fossil found with the exception perhaps of sponges and ferns. They dominated the earth for a period 75 times longer than man's total existence. Many specimens of brachiopods can be found; they are bivalved animals whose shells resemble an extremely symmetrical clamshell. Many invertebrates which made their shells of lime (calcite) also lived in such profusion that the accumulation of their shells on the sea bottoms formed, to a large part, the hardened limestone deposits that later formed many of the mountains in the Bob Marshall Wilderness.

The South Fork trail cuts through a very unusual deposit above Spotted Bear Ranger Station. This vein is about a foot thick; the material is black but does not resemble coal in texture. It can easily be ignited with a match.

Dr. Lowden, then head of the geology department at the University of Wisconsin, analyzed some of this material in the laboratory and stated that it was unique, that he had never analyzed anything quite like it. Lowden said it probably was "sludge" that had settled in an ancient oil pool.

The often-mentioned "Chinese Wall" forms the Continental Divide from Larch Hill on the north to Haystack Mountain to the south, a distance of about 12 miles. This sheer cliff faces the Sun River drainage to the east. It is unscaleable except for experienced, properly equipped mountain climbers. It is nearly 1,000 feet in height for the entire distance and is made up entirely of Cambrian limestones which are over 300 million years old. The layers of rock have been subjected to tremendous stresses from within the earth, and sediment deposited there began to be folded and broken by great faults and elevated into systems of mountain ranges, resulting in many gigantic faults that can be traced in the Swan, Flathead, and Lewis and Clark ranges. The most widely known and one of the grandest of these faults is the Lewis overthrust which has been traced and mapped from Canada southward through Glacier National Park and throughout the length of the Sun River unit where it lies several miles west of the North Fork of Sun River.

Along the surface of this break in the earth's crust, the ancient Beltian rocks were shoved up over the younger Mesozoic rocks and moved eastward as much as 12 miles in the Glacier Park region and probably 9 or 10 miles in the eastern portion of the wilderness.

The glaciers in the wilderness were formed at two, or more, different times: first, possibly 2 million years ago; and second, sometime between 30 and 50 thousand years ago. The present glaciers in Glacier Park and elsewhere are dying remnants of what were once vast ice sheets covering the mountains.

The sheer cliff of the "Chinese Wall" is the result of ice action, as are many U-shaped valleys formed as glaciers filed or rasped their way downward through the solid rock as they flowed to lower elevations. Today, geologists know that the mountains of the Bob Marshall Wilderness were elevated from an old sea bottom and were built of sedimentary rocks composed of sands, mud, shells of animals and limey deposits of plants. Rainwater and streams eroded the rocks during millions of years; and, finally, within the last 50,000 years, ice sculptured the mountains to their present rugged, scenic beauty.

Although Firefighter Mountain is not in the wilderness, it is the same strata and formation as Great Northern Mountain immediately to the east, except that it is upside down, indicating that it has broken away from the parent mountain and rolled half over.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

story/chap21.htm Last Updated: 12-Sep-2011 |