|

The National Forests of the Northern Region Living Legacy— |

|

Chapter 8

The World War II Experience

"The war," historian Harold K. Steen observed, "was the last hurrah for many forestry pioneers and brought a change of direction for American forestry." [1] World War II marked the end of one era in the history of the Northern Region and the beginning of a new era. It was in some respects, as Ranger Ed Slusher observed after 30 years of forestry service in the region, a time of transition from the older custodial era to the new developmental, managerial era. [2] More immediately, World War II brought sharp changes in forest practices and activities within the region and brought the years of the Great Depression and the New Deal to a close. The Civilian Conservation Corps and Forest Service personnel both left the forests for the training camps and battlefields. Civil defense, operating efficiencies, and war production became paramount considerations. Change would become dramatic and sometimes traumatic. War brought more rapid change; but, to be sure, change was already in the air.

By 1940, the Forest Service had come a long way from the old "horse and buggy days," observed the Sunday Missoulian. "Thirty years ago the use of parachutes, airplanes, and radio in forestry was unthought of," as were trucks and "truck trails," paved highways, and tourism. There was also, the writer observed, a growing demand that "all of our forest lands be handled for the benefit of future generations as well as the present." Such public sentiment, "once aroused," is a powerful thing. [3] The war perhaps delayed for almost a decade the awakening of such powerful public sentiments. The attack on Pearl Harbor by the forces of the Empire of Japan on December 7, 1941, abruptly focused sentiment, thought, and action on national defense.

A month after Pearl Harbor, Regional Forester Evan W. Kelley reflected on the situation nationally when he observed that in Region 1 civil defense programs were still highly disorganized. What would happen within the region or elsewhere was speculative. He was concerned about incendiarism and saboteurs, and he believed that the workforce would be depleted rapidly by the draft, enlistments, and migrations. The region would have to eliminate "things nice to have and nice to be done" he said. "If the forests and ranges can be saved from enemies and so managed that they will contribute their part to defense needs and still leave them in condition to produce more, we will have done our part," he explained to his division chiefs. [4]

Over the next few months, the forests became increasingly silent as Forest Service, Civilian Conservation Corps, and commercial employees left for military service. The stillness was particularly marked by the closing of CCC camps and the departure of the thousands of formerly unemployed youths who now had other duties. During its time, the CCC had invested an estimated 8.5 million person-days in the construction and maintenance of roads and trails and in fighting fires and supporting forestry programs. Some 3,476 miles of truck trails and 338 lookout houses and towers, as well as bridges, fencing, telephone lines, ponds, campgrounds, ranger stations, and ski lodges had been established within the region with the labor and assistance of CCC workers. [5] Kelley observed that the Forest Service must resort to "older men in their fifties and sixties, and boys of high school age," to replace the lost manpower. [6] Women, too, soon came into the ranks as lookouts, guards, and professional staffers.

Fewer Personnel but More Timber Production

Kelley himself became one of those foresters assigned to more urgent war-related duties elsewhere. By late January 1942, he was in Salinas, California, heading up a Government defense program designed to provide emergency supplies of crude rubber made from the desert guayule plant. Placed under the authority of the Forest Service, and in cooperation with the Bureau of Plant Industry, Kelley and his associates planned to plant 2,000 acres of the guayule in 1942, and by early 1943 some 50,000 acres of guayule were scheduled for planting. Kelley helped design and begin the operation of a rubber factory, which he said, in early 1943, was producing "better, cleaner rubber" than ever before. "Have lived, slept [in] that factory for the past year," he said. The two operating guayule extraction plants were producing 30 tons each day. The material was used for the inner plies of tires and, when mixed with natural rubber, could be formed into bulletproof fuel tanks for airplanes. Although the operation continued until the end of the war, by early 1943, according to Kelley, the program was about to fold. [7]

Kelley went to Washington, D.C., in March to protest announced cutbacks in new plantings. He discovered that other synthetic rubber programs were moving so rapidly and were so promising that the slower producing guayule project was being cut back, but a firm decision on what to do had not been made. Seedling nurseries in the Mesilla Valley of New Mexico; Phoenix, Arizona; Edinburg, Texas; and Oceanside, Bakersfield, and Indio, California, were being eliminated. The thousands of men and women who had worked so hard to get the project going "in the belief that they were doing and giving aid to their country in times of distress" would be shocked to hear the news, he said. "I may be home to enjoy the summer in the Northwest," he speculated. [8]

Despite Kelley's early departure, Acting Regional Forester C.S. Webb was determined to maintain business as usual insofar as possible. Available manpower and money would be stretched to maintain as many services as possible, but the situation seemed to change daily. When Webb became Acting Regional Forester upon Kelley's departure in January 1942, E.D. Sandvig moved from range management into Webb's position as the head of the Division of Operations. I.V. Anderson, Chief of the Division of Wildlife Management, went to Washington, D.C., on special assignment. C.A. Joy, who worked under Sandvig in range management, filled the two slots vacated by Sandvig and Anderson. Those who remained in the region worked longer hours at more tasks. Engineers such as J.B. Yule, Donald Sawhill, Frank Cool, E. Morris, and Frank McLeod received assignments with the Army Engineers, as did ranger C.K. Lyman and guard E.R. Augustin. Most had left the region by March 1942. There would be no replacements. [9]

Despite heavy personnel losses, declining Federal appropriations to the region required even further employment reductions. Webb wrote his forest officers a "personal letter" in April 1943 to explain the situation. Personnel reductions were required because of budgetary constraints on the basis of efficiency ratings, with credit given to persons having military service. Moreover, by July, an additional 30 separations would be required, he advised, to make room for people such as Evan Kelley who were being reassigned from the guayule project. Those who had worked long hours were being paid overtime, he said, under the theory that if fewer people worked longer hours they would be releasing others for more important war jobs. Similarly, he said, this "furlough" coming to some should be regarded not as an end to one's employment, but as a temporary contribution to the war effort. "It is my hope," he said, "that at the conclusion of the war the Forest Service will be built up again to serve the public of this great democracy in the post-war adjustment program." [10]

In some respects, the decline in personnel was somewhat consistent with the shift in national policy from protection of the national forests to production of lumber for defense. In May Chief E. H. Clapp reported alarming shortages of lumber and timber products essential for the war effort and estimated that national lumber requirements for 1942 would be 39 billion board feet, not the 8 billion board feet estimated earlier. In response to estimates of 12 billion board feet needed to meet current army, navy, and maritime construction projects, the War Production Board froze softwood construction lumber millstocks. Lumber did not exist, Clapp explained to Secretary of Agriculture Claude R. Wickard, for defense housing, farm construction and repairs, and grain bins. A thousand cargo trucks were being built each day, he said, all using wood bodies; and a "very large program of wooden ships" was under consideration. He attributed critical shortages to the failure to foresee the "magnitude of requirements," shortages in metals and replacement parts for harvesting equipment limited transportation, labor shortages, and real inadequacies of timber supplies in many areas. Clapp advised creating a Forest Products Administration to stimulate and supplement production by private agencies. [11]

Elers Koch reported to Acting Regional Forester Webb that, contrary to the implications of Clapp's letter, there was no lag in lumber production in Region 1. The cut for the first quarter of 1942 was 10 percent greater than in 1941. There were almost no idle mills, he said, and most were working two or three shifts. The only factors limiting production were weather and bad roads, but if all regions were working as well as Region 1, there should be no difficulty in producing the required 39 billion board feet. Koch thought that rather than set up a new agency, such as that urged by Clapp, the Forest Service might simply loan men to the War Production Board. [12]

Philip Neff, Senior Logging Engineer, believed that the 39 billion board feet could not be met nationally, largely because of weather and "acts of Government." The lumberman, he said, "has had little encouragement and sympathetic advice, but a lot of costly regulation. And now the government has imposed ceiling prices." Lumbermen would not support a "Forest Products Administration" he believed; "they would be very suspicious of the Forest Service's intent." [13] Under intense pressure from every quarter, and understaffed at home, the Forest Service in Region 1 and elsewhere turned from an emphasis on protection to production.

The Northern Region harvested more timber from the national forests during the last 6 months of 1943 than in any previous half year since the forests were organized. Nearly 150 million board feet were harvested, and another 167 million board feet were already scheduled for cutting. The total 1943 cut of almost 317 million board feet exceeded the 1942 harvest by 46 million board feet. The largest commercial cut occurred on the Kaniksu (36,281,000 board feet), with other cuts totaling 28,307,000 board feet. Harvests on the Kootenai totaled over 83 million board feet, and record harvests of 39,758,000 board feet were recorded on the Nez Perce due to the construction of wartime emergency roads to facilitate the harvest. Total timber sales receipts from the national forests in all regions in the last 6 months of 1943, at $6.3 million, were more than double the receipts in the comparable period of 1942. County coffers, which received 25 percent of total receipts, were substantially enriched by the sales. [14] The region fully met its wartime lumber production obligations. There were, to be sure, adverse by-products. Curiously, one of those was fire, a threat and a reality that lasted well into the postwar years.

"Careless Matches Aid the Axis"

In 1942, Secretary of Agriculture Claude R. Wickard opened a campaign to prevent forest fires, explaining that "destruction in our forests today by carelessness with fire is equivalent to sabotaging the nation's war program." [15] December of that year, Congress approved legislation that made the willful destruction of timber and forage by fire a form of sabotage comparable to the malicious damage of other war materials, subject to heavy fines and imprisonment." [16] The highway patrols of Montana and Idaho joined the Forest Service in fire prevention and patrol. [17]

Women and Youth at War in the Northern Woods

Regional Forester Evan Kelley, who returned to his duties in the region in the fall of 1943, announced that critical labor shortages would be partially met in the summer of 1944 by recruiting 16- and 17-year-olds not already employed in critical war work. These youths would do blister rust control, slash disposal, trail maintenance, and other essential jobs. They would be given intensive training in firefighting, safety practices, and woodsmanship. Student fire camps, Henry Viche recalled, were held in the region in the Spring of 1942 and 1943. The student fire crews provided the major firefighting force for the entire Northwest, he said. Although the blister-rust control work, which had been accelerated by the CCC crews, entered a period of "austerity" during the war, some young people, foreign nationals, and older people manned the blister-rust control crews.

Some students served as lookouts, but perhaps with less success than did older women, who also were coming into the wood-and forest-products industries in greater numbers as the war progressed. For example, one very young and lonesome lookout on the Lolo finally decided he was having a heart attack and left a note for the ranger to that effect. Another, very young but just married, was described as having neither the experience nor the knowledge for the job. Others, such as Willard R. (Bill) Fallis, who enrolled as a freshman in forestry at the University of Montana in 1941, were extremely effective in seasonal jobs ranging from a lookout (Timber Mountain) on the Kaniksu to administrative guard, firefighter, packer, and range surveyor variously on the Teton, Beaverhead, and Helena. [18] Generally the young men and the women received good training and performed well.

During the 1943 fire season, more than 50 women stood as lone sentinels on the high mountain peaks, splitting their own wood; packing in their supplies and water; and reporting weather conditions, smoke, and—presumably— aircraft movements. Among these lookouts were Helen Conover at the Williams Peak Lookout on the Lolo National Forest; Hollis Stritch, a Missoula housewife who spent her summers at the West Fork Butte Lookout on the Lolo; and Mrs. Ear Hupp, a housewife from Newport, Washington, at King's Mountain Lookout on the Kaniksu. Other female lookouts on the Lolo included E. Clarine Moore, Klara Erickson, Verdie Sward, Mildred Harkinson, and Mrs. R. King, described by an inspector as "an experienced ranch woman, who knows how to take care of herself and is industrious and competent." Harriet Linn, who later described the drudgery and sheer hard work of the lookout, and Ruby Moore were other women on the Lolo. Many women served as dispatchers, truck drivers, camp cooks, and part-time (often double-time) office workers. [19]

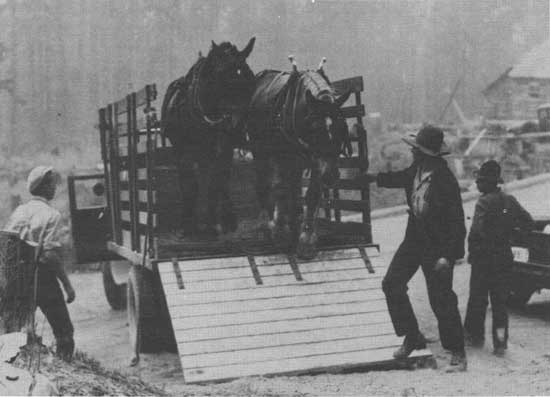

Wartime demands to expand timber harvests compounded labor shortages. For example, the construction of a timber access road on the Clearwater National Forest, to open up stands of white pine timber and cedar poles in the Musselshell Creek area, began in May 1943. The 12.5-mile road began from the paved highway at Pierce, Idaho, passed the abandoned Brown's Creek CCC camp (which became the project headquarters), and continued to the Musselshell work center. According to the recollections of J.F. "Jack" Hamblet, who supervised construction, 4 miles of "new" construction crossed Brown's Creek summit, and the remainder of the roadbuilding involved reconstruction of an existing older road, improving grades, and installing drainage systems. "Construction was not difficult and the job would perhaps otherwise be of little interest were it not for two unusual groups of people involved in the construction." [20] Labor crews included women and Italian internees.

The internees were Italian merchant seamen whose ships were in U.S. ports when World War II began. They were technically Italian nationals, not prisoners of war, under the custody of the Immigration Service for the duration of the war. Most had never seen forested lands such as those in the Northern Region, nor labored at such tasks as roadbuilding or construction; but most, said Hamblet, enjoyed this freedom from the internment camp at Fort Missoula and exhibited "joy and wonderment" at the strange new sights in the woodlands of the Northwest. "It was remarkable," he said, "how fast they learned to fall [sic] timber, deck logs, install culverts, trim backslopes, and perform many other jobs they had never before seen." And it was all done in "first class" style, with ship's pursers providing office help, barbers giving everyone a weekly trim, and cooks and bakers offering up delicious Italian and American dishes, with a variety of fancy pastries for dessert. During leisure time the internees played "bocce," carved beautiful scale-model ships, did weaving, wrote letters home, and walked in small groups through the woods and meadows. [21]

The roadbuilding project experienced interminable delays, however, because of the lack of sufficient drivers to keep the trucks moving stone to the crushers and back to the road bed. There were simply no drivers available anywhere in the region. Finally, the wives of some of the supervisors offered to "give it a try." Other Forest Service wives joined in, received assistance from women in Pierce (including one grandmother), and, after a short driving course from Tom Moran, within the week were driving 13 dump trucks over narrow mountain roads.

"They seldom missed a shift, driving in dust and rain, and later over snow-packed and icy roads, always bucking the logging traffic, till the job was closed in November. In all that time they never lost a load or had a single accident of any kind." [22]

Women were also at work in lumber mills and factories. During an orientation tour in October 1944 with P. (Pete) D. Hanson, who was replacing him as Regional Forester upon his retirement, Kelley described the almost frenetic lumber production at the Potlatch Forests, Inc., sawmill in Lewiston, Idaho. "Lumber," he said, "was flowing from the four sides and the gang saws, producing veritable rivers of boards and dimension materials." Presto-log machines were "rolling out tons of logs hourly," and the warehouses were bulging with fuel manufactured from wood wastes. The box factory, he said, was working at a "dizzy pace," and hundreds of girls and women were employed there. "One cannot help but wonder how the forests in the Clearwater drainage can possibly feed the hungry maws of that plant continuously," he observed. [23] Forest Service personnel, young and old, men and women, contributed to the war effort in many ways.

County Revenues From Timber Harvests

The exigencies of war resulted in a large increase in the harvest of lodgepole pine, fir, larch, spruce, hemlock, and cedar. Before the war, ponderosa and white pine comprised 75 percent of the timber harvest, but by 1945 accounted for less than 50 percent. Axel Lindh, chief of timber management for the region, speculated that the trend toward lodgepole pine, fir, and other previously ignored trees could sustain a substantial timber industry. Otherwise, he said, "wartime overcutting must be made up by reduced timber harvest in the post-war period." [24]

County receipts from timber sales on Federal lands, under the 25-percent apportionment, reached unprecedented levels in 1944 with the dispersal of almost $143,000 to Montana and $228,000 to Idaho. Lincoln and Flathead counties in Montana received the largest apportionments, with $50,792.91 and $14,071.05, respectively; Shoshone and Idaho counties in Idaho received $50,144.56 and $29,750.63. The smallest payment went to Jefferson County, Idaho, in which 1 acre of the Targhee National Forest lay. In addition to the 25-percent return to the counties, 10 percent of national forest receipts was reserved for the construction of forest roads and trails within the region. [25]

Buy Bonds, Do War Work, Prevent Forest Fires

Patriotic slogans captured the popular imagination and produced determined support for the war effort. Among those seen and heard in the region's forests were: Say "HEIL HITLER," when you throw a lighted match into the forests, you are helping the Axis; keep the forests green for homecoming heroes; buy all the bonds you can, and then help more by preventing forest fires; and remember—rumors are a weapon of the enemy! The fourth War Loan Drive in 1944 resulted in a 10-percent subscription of gross salaries by Region 1 personnel for war savings bonds. The Missoula Chapter of the American Women's Voluntary Service instituted a "train service" for military personnel traveling through the area on the Northern Pacific Railroad. The women offered soft drinks, coffee, milk, cigarettes, magazines, playing cards, cookies, sandwiches, and a friendly ear. Local merchants contributed cash or goods, and Region 1 sponsored a special collection for the train service in June 1945. [26] People in Region 1 zealously supported the war effort.

Between December 7, 1943, and August 1945, 735 Forest Service employees left the forests and went to war. Many of them served in combat, and some even operated with special forces behind enemy lines. Nineteen were reported killed or missing in combat. [27] On April 12, 1945, President Franklin D. Roosevelt died and Harry S. Truman took the oath of office as the last great battles for Europe were being fought. On May 8, 1945, Germany surrendered to Allied forces, but victory over Japan appeared to be far off. That victory came closer, however, with the explosion of the first atomic bomb over Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and a second over Nagasaki on August 9. Shortly thereafter, on September 2, 1945, General Douglas MacArthur formally accepted Japan's surrender aboard the battleship Missouri in Tokyo Bay.

Postwar Adjustments

In June, July, and August of 1945 the region already appeared to be in the midst of preparations for the postwar era. In June, Regional Forester P.D. Hanson established the Division of Land Use Coordination in the Regional Office. The division was designed to more closely coordinate Forest Service operations and planning with State and other Federal agencies and private forest managers. Because of their resources of water, timber, forage, recreation, and wildlife, the national forests, Hanson explained, "are so closely linked with the welfare of the entire region that this coordination is essential." [28] In some respects, this action helped implement the Sustained-Yield Forest Management Act approved by Congress on March 29, 1944, which involved the Departments of Agriculture and the Interior in cooperative programs for both public and private forested lands. But it also anticipated the Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act of 1960, which directed the Forest Service to give equal consideration to outdoor recreation, range, timber, watershed, wildlife, and fish resources and needs.

Hanson appointed M.H. Wolff, who had joined the Forest Service in 1909 and whose work had concentrated on recreation, land use planning, and special use permits, to head the division. R.U. Harmon, who transferred into the region from the North Central Region to replace Wolff in the Division of Recreation and Lands, also had strong recreation credentials. [29] Nevertheless, the region was largely unprepared for the enormous public demand for recreational opportunities and facilities that lay just ahead. Planning for recreation and repair or expansion of facilities had been eliminated during the war, and management planning and organizational changes had been suspended for the duration. Now that the war was nearing an end, some attention could be given long-delayed plans.

On July 1, 1945, the Gallatin and Absaroka National Forests were consolidated and the Ennis District of the Gallatin was transferred to the Beaverhead National Forest, while part of the Shields Ranger District was transferred to the Musselshell District of the Lewis and Clark National Forest. It was, said Hanson, consistent with the realities of faster communication and modern transportation that made it possible to administer larger forest units than when the forests were first organized. [30] The region also announced the establishment of a forest products utilization unit, under the authority of the Northern Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, at Missoula. This laboratory, headed by I.V. Anderson, who had just returned from his war assignment in Washington, D.C., where he assisted in the development of plywood and veneer products, would work to assist local industry in developing diversified manufacturing processes to more efficiently utilize forest resources. [31] In August, Hanson announced numerous personnel changes, including transfers between regions, in anticipation of former employees returning to their old jobs and an influx of personnel fresh from the armed services joining the ranks of the Forest Service. In September, the region adopted a standard 40-hour work week in compliance with the new Federal Employees Pay Act, which, among other things, prohibited payment for overtime work except in emergency situations. [32] Thus, by the end of 1945, change was in the air. Forest uses were changing, people were changing, and the rules were changing. No one, however, could anticipate the extent of the changes that would occur in the years ahead. For the most part, it seemed to be very much a case of business as usual, and a welcome return to the order, stability, and familiar faces of the pre-war period.

Timber cuts for the last quarter of 1945 declined by almost 8 million board feet from the third quarter. In the early spring of 1946, the region announced the unprecedented sale of 4,200 acres of lodgepole pine timber from the Lewis and Clark National Forest—unprecedented in that lodgepole pine had been virtually unmarketable before the war but now was becoming heavily demanded for pulpwood, posts, poles, and even sawlogs. Larch also became an increasingly important timber source; 21 percent of all timber being cut in the spring of 1946 was larch, where in 1940 larch was virtually unwanted, constituting only 2.9 percent of all the timber cut on the region. In 1940, 60.7 percent of all sawlogs cut were white pine, compared with 13.2 percent cut in 1945. [33] This data only hints at the postwar changes occurring in the wood-products industry. By April 1946, it was apparent that the Nation's demand for lumber and lumber products had become insatiable.

The rising demand for timber, the growing interest in recreation and public access in the forests, and the necessity for more efficient fire control created the need for more forest roads in the region. By April 1946, Regional Forester Hanson was advertising for experienced engineers and engineering aides for road construction. The base pay ranged from $1,900 to $3,640 per year. Arthur (Art) Kahl, who came to the region in 1934, had for some years been one of the few engineers in the region, supervising most of the bridge construction until his retirement in 1961. [34] Road and bridge construction became a major effort of the Forest Service in the postwar years, facilitated by the accumulation of county road funds and new congressional appropriations. The expanding forest and public road systems aided in the suppression of forest fires but contributed to a greater fire hazard in the form of a growing number of visitors.

Fire Suppression and Smokejumping

By the war's end, both public and private forest funds in the region were veritable tinder boxes. |

The region had been extremely fortunate to have experienced relatively few serious forest fires during the war years. The intense public campaigns to reduce fire hazard as a patriotic duty undoubtedly contributed. Student volunteer fire units, such as those trained and supervised by Henry (Hank) J. Viche in 1942, performed extremely well. But the simple fact remained that there were fewer fires between 1941 and 1945 than there had been in the prior 4-year period. In the 4 years following the war, however, forest fire truly became the region's number one enemy. The 1940's, and the postwar era closed with the tragic Mann Gulch fire of 1949 (described later in this chapter). C.S. Crocker warned of the extremely combustible state of the forests at the close of the war. Labor shortages and urgent wartime timber production goals resulted in the neglect of the usual cleanup of brush, slash, and debris. By the war's end, both public and private forest funds in the region were veritable tinder boxes. [35]

Improved access roads capable of supporting motorized equipment such as trucks, tractors, and bulldozers improved firefighting performance over that of earlier years. Aerial fire control also progressed measurably during the war years, stimulated in part by the shortage of manpower in the traditional fire crews. The first aerial fire patrols in Region 1 began in 1925, when Forest Inspector Howard R. Flint recruited two Air Corps reserve lieutenants, Nick Mamer and R.T. Freng, to fly reconnaissance flights over parts of the forests. In 1929, a supply drop was made to a ground crew fighting a fire in remote country, and experiments with aerial photography were being conducted. In 1934, a few experiments were conducted in the Intermountain Region, with firefighters jumping into forests by parachute, but the idea was dismissed as too dangerous. Henry Viche recalled that the first actual drop of a fire camp was made on May 31, 1936, on the Spruce Creek Fire (Powell Ranger District) on the Lolo National Forest. [36] An aerial experimental project conducted by the Washington Office, which was transferred first to California and then to the Pacific Northwest Region, became the conduit for the advent of smokejumping.

In 1942, with a critical manpower shortage in the region, greater reliance was placed on the smokejumping crew. |

Experiments with cargo dropping and aerial spraying with water or chemicals were abandoned in 1939. The surplus funds were diverted to a contract with the Eagle Parachute Company of Pennsylvania, whose personnel experimented with jumps into areas of the Chelan National Forest in Washington. The tests were so successful that Region 1 and Region 6 each established a squad of smokejumpers for the 1940 fire season. The Johnson Flying Service conducted training at a special camp in Missoula. Two brothers, Dick and Bob Johnson, with Dick Vance, flew the planes and taught "parachuting." During the fire season, in July 1940, the Johnsons also dropped an estimated 300 tons of supplies to fire camps in the region. The first fire jump by Forest Service personnel was made on July 12, 1940, by Rufus Robinson and Earl Cooley on the Nez Perce National Forest. "Smokejumping" quickly adapted to other needs when, 3 days later, Chester N. Derry parachuted onto the Bitterroot to provide assistance to airplane crash victims. U.S. Army staff officers visited the parachute training camp that summer, and the next year adapted some of the techniques to the training of paratroopers at Fort Benning, Georgia. In the spring of 1941, smokejumping was assigned exclusively to Region 1, which was to render services when possible to Regions 4 and 6 (the Intermountain and Pacific Northwest Regions). The Johnson Flying Service provided the planes, pilots, and services. Region 1 jumpers fought nine fires in 1941 and saved the region an estimated $30,000 in protection costs. [37] In 1942, with a critical manpower shortage in the region, greater reliance was placed on the smokejumping teams.

|

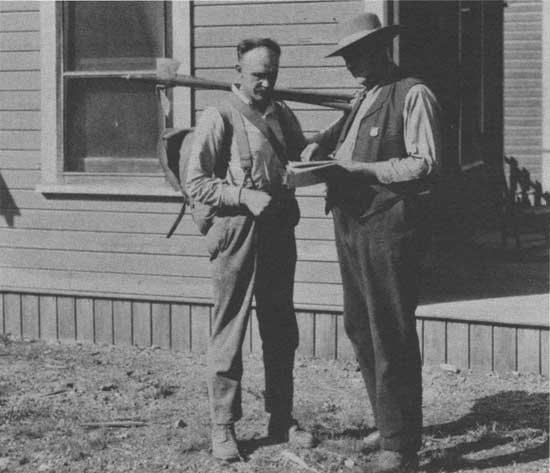

| Smokechaser receiving instructions during 1924 fire season. |

Although the 1942 fire season was relatively mild, smokejumpers extinguished 31 fires and were assisted by ground crews on four other fires, resulting in an estimated savings of $66,000 in suppression costs, not to mention the savings in timber value resulting from early suppression of fires in remote areas. However, by 1943 the region found itself unable to staff even one smokejumping crew. Only five experienced jumpers were available and intensive recruiting efforts turned up only four other young men who had been turned down by the Army because of minor physical defects. Providentially, inquiries were made by (4—E) conscientious objector draftees who were stationed in work camps in the northern forests. The Forest Service recruited volunteers from these encampments and finally selected 62 trainees from 300 applicants for smokejumping training. The new crews fought 47 fires with little ground support available. The regional smokejumping school also trained rescue units from the U.S. Coast Guard, the Canadian Air Observer Schools, and the U.S. Army during the 1943 fire season. By 1944, smokejumping ceased to be experimental and became part of the standard operating procedure in Region 1. Regular ground units were reduced in that year, and fire suppression depended heavily on the smokejumping units. Ralph Hand, who directed the para hute operations, added air rescue teams that included medical doctors trained to jump into timber. The Region 1 "Trouble Chuters" received national recognition in an article published by Collier's magazine in December 1944. [38]

|

| Smokejumpers before taking off for a fire. Camp Menard, Lolo National Forest. 1952. |

Smokejumping proved to be a particularly effective and economical method of fire control in back-country areas, which were characteristic of the region. |

Experienced jumpers from the public service camps were joined by some returning veterans in 1945, raising total enrollment in the smokejumping program to 220. Most of these were stationed at Missoula, but other camps were located in McCall, Idaho; Twisp, Washington; and Cave Junction, Oregon. The enlarged program encountered a more acute fire season in 1945, when jumps ranged from California to Washington, Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks, Native American lands, and, on one occasion, across the international boundary into Canada, The region also sponsored training of the 555th Battalion, a black paratroop unit intended to suppress fires started by Japanese incendiary balloons. When the balloon menace failed to materialize, the paratroopers were used in aerial fire suppression. [39] Smokejumping proved to be a particularly effective and economical method of fire control in back-country areas, which were characteristic of the region.

When the war ended, the Army's CPS program was abolished and the Forest Service recruited returning veterans to fill the smokejumping units. The spectacular achievements of the Region 1 smokejumping units inspired Twentieth Century-Fox to produce "Red Skies Over Montana," a movie featuring smokejumpers. In 1952, Congress established a permanent Aerial Fire Depot at Missoula, which was dedicated by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1954. By 1971, the Johnson Flying Service in Missoula which had begun by ferrying jumpers and supplies in a 1929 Ford tri-motor, added a Lockheed Electra that could ferry 93 jumpers at 350 miles per hour. Although tremendously successful, the smokejumping venture was not without casualties. Dick Johnson died in a plane crash near Jackson Hole, Wyoming; pilot Bill Yaggy died in a plane crash near Dixie, Idaho; and Dave Godwin, the fire control chief in the Washington Office and "godfather" of the parachute project, also died in a plane crash. [40]

The region placed greater reliance on aerial fire detection and smokejumping in the years following the war. The Coeur d'Alene, for example, initiated daily aerial fire patrol flights in 1947. The several hundred smokejumpers on duty in the region in 1948 were only a part of the army of some 7,000 seasonal employees and 1,200 permanent Forest Service employees available for fire suppression work. Generally, casualties, even injuries, had been few in Region 1 until the disastrous Mann Gulch fire on the Helena National Forest in 1949. [41] Fire suppression became increasingly important in the face of growing nationwide shortages of lumber for new housing as the Nation entered the era of the baby and building booms.

National Lumber Shortages

Regional Forester Pete Hanson explained that the decline in U.S. private timber supplies acted to increase the relative importance of timber on the national forests. Public demands for lumber for new housing and home repairs surged. Hanson said, "People have been asking...why they can't get all the lumber they want, when they want it." The Forest Service was accused of hoarding the Government's timber resources. "The fact is," Hanson explained, citing a report from Chief Lyle F. Watts, "the Nation's wood pile has been reduced by more than 40 percent" in the past 36 years. Wartime demands, and the new postwar housing boom, were further depleting timber. [42]

Timber harvests were accelerated after the war by massive allotments from the National Housing Administration to the Forest Service for the construction of roads, in addition to the expenditure of surplus county funds received from timber sales during the war years and regularly appropriated road funds. Region 1, for example, received $3 million from the National Housing Administration for road construction in 1946, and spent an additional $2 million on timber access roads from appropriated funds. In March 1947, A.H. Lindh, Assistant Regional Forester in the Division of Timber Management, reported that in the 10-year period between 1937 and 1947, Region 1 timber sales had risen from 105.8 million board feet to 394.8 million board feet. In that period, the percentage of western white and ponderosa pine harvested had declined from 62 percent to 38 percent, with Douglas-fir and larch (23 per cent and 24 percent, respectively) taking up the difference. Production on the Flathead National Forest had risen from 2.3 million board feet in 1937 to 54.2 million board feet in 1947. The next year, 1948, the region harvested 410.9 million board feet, with heaviest production from the Coeur d'Alene (63.3 million board feet), followed by the Kootenai (55 million), the Kaniksu (53.2 million), and the Flathead (31.5 million). [43] Faced with heavy public and congressional pressures for timber production, the Forest Service became increasingly concerned about preserving timber resources for future use.

The Forest Service did enlarge the scope of its protection operations under the Clarke-McNary Act (1924), which provided for financial contributions to the States to assist organized forest protection districts in protecting State and private lands until the States could fully resume their protection responsibilities. The act also provided for assistance to private landowners in implementing basic forest practices on their forested lands, and it promoted the production of trees (planting stock) in State nurseries. The Norris-Doxey Act, passed in 1937, provided for cooperative Federal-State programs to promote farm forestry. Disease and pest control efforts, as well as cooperative efforts through the States, were enlarged under the authority of the Forest Pest Control Act of 1947. [44]

In 1948, pursuing the interest in maintaining continuing use of resources in the national forests, Region 1 began planning its first "sustained yield unit" under the authority of the 1944 act of the same name. The proposed Kootenai Sustained Yield Unit, Hanson said, was specifically aimed at ensuring the continuing economic welfare of the communities of Libby and Troy in northwestern Montana, which were "dependent to an unusual degree upon the proper management of the tributary forest lands." The plan called for the management of 170,000 acres of forest land owned by the J. Neils Lumber Company under the direction of and in cooperation with the Forest Service, and compensation to the lumber company by sales "without competition" of timber from selected tracts of the Kootenai National Forest. [45] It was the first such arrangement in the region.

Growing public demand for forest resources did not encompass saw timber alone. The region was becoming increasingly conscious of the growing numbers of hunters, anglers, campers, and tourists. Winter sports, in the past little more than a local pastime, began to attract large numbers of "outsiders" into the region. Interestingly, mining, watershed, wildlife, and range uses intruded into the collective consciousness of the region only slightly. For the most part between 1941 and 1949, the Northern Region was emphasizing timber production and fire suppression. If fire had not already been preeminent among foresters' concerns, certainly the Mann Gulch fire would have made it so.

The Mann Gulch Fire

The region announced the creation of the 28,562-acre "Gates of the Mountains" wild area on the Helena National Forest in June 1947. In this scenic and recreational area, located on the Missouri River between Helena and Great Falls, Montana, timber cutting, road construction, and manmade improvements other than those essential for fire protection, water, and sanitation were prohibited, so that people could enjoy wilderness vacations under the most natural conditions possible. It was within this area that Don Barker, a lookout on Colorado Mountain, some 30 miles distant, spotted smoke on August 5, 949. District Ranger J. Robert Jansson saw the same smoke from the Helena airport about the same time. Jansson and a pilot and acting ranger named Hersey flew over the fire in Mann Gulch at 12:55 p.m. and estimated its size to be about 8 acres. It was "smoking strongly." Another fire was located about 9 miles south of the Mann Gulch fire. [46] The inaccessibility of the area dictated the use of smokejumpers, followed later by ground crews.

Three hours later, 15 smokejumpers with equipment landed at the site of the fire, now estimated to cover about 50 to 60 acres. The jumpers spent approximately 2 hours setting up their equipment and reparing their approach to the fire with no evidence of danger. They then headed down the gulch from the ridge toward the river.

The Mann Gulch fire was a tragic and traumatic affair, which long remained in the hearts and minds of the people of the region. |

Meanwhile, Jansson and a crew of 10 reached the fire site by river about 5:00 p.m. They were followed by Hersey, who, with a crew of 9, headed for the ridge above the fire. Meanwhile, a fire guard, James O. Harrison, arrived at the fire from the nearby Meriwether Camp. Harrison met R. Wagner Dodge, the smokejumper foreman, at the ridge above the fire site and, with the remainder of the smokejump crew brought up under crew leader William J. Hellman, the party proceeded down toward the river. Dodge realized that the fire was burning more intensely and moving rapidly toward them. He doubled back toward the ridge at a fast pace, had the men discard their heavy equipment, and finally, as the fire moved within 500 feet, decided to take a stand on a grass-covered slope on a side ridge. Dodge attempted to light a backfire and urged the men into the small burned area, where he lay close to the ground, but they refused to follow. Instead, the crew headed for apparent safety through an unburned neck. Two of the crew, Robert Sallee and Walter Rumsey, made it through to a rockslide just over the ridge, but the rest were caught as the main fire passed through the unburned passage. [47]

Dodge and Sallee went for help and arrived at Meriwether Camp at 9:00 p.m. Medical help was called for in Helena, and about midnight Jansson, with a small group and two doctors, reached the site of the worst fire disaster in the history of Region 1. Twelve of the 15 smokejumpers died, as did Harrison, who had arrived at the site on foot. By early morning of August 6, the fire was almost beyond control and fire crews were brought in from all over the region. They included local farmers and ranchers and volunteers from the Reclamation Service, the Highway Patrol, and the Army Air Force Base at Great Falls. More than 450 firefighters finally halted the fire on August 7, and by the 10th they had the fire under control, More than 5,000 acres of the wild area had burned. [48]

A special board of inquiry organized by the Chief of the Forest Service concluded that there had been no evidence of wrong decisions or actions, and that the "blow-up" of the fire could not have been reasonably expected. The board urged greater emphasis on training for firefighters, and intensification of studies and research in fire behavior. [49] The Mann Gulch fire was a tragic and traumatic affair, which long remained in the hearts and minds of the people of the region.

|

| Smokejumpers headquarters, Lolo, National Forest |

|

| Firefighting 1934. Nez Perce National Forest |

Entering a New Era

Firefighting remained a major priority in the region. The year 1953 brought other major fires, and in intermittent years thereafter the region was sorely taxed, despite the adoption of modern fire control techniques, smokejumpers, helicopters, and bulldozers. Gradually, the Nation's enormous appetite for lumber began to be filled, and the pressures on the national forests for timber production began to be tempered by concerns for conservation and preservation and an increase in nonconsumptive uses of forest resources. In this new age, the public became more acutely aware of the great heritage of the Nation's forest resources, and better organized to impose its own particular concern on the style and purpose of forest management. "Other" direction, from Congress and wilderness organizations, and cooperation and planning as well as new technology relating to silvicultural practices began to change the style and structure of management by the Forest Service in Region 1 and elsewhere.

|

| Kaniksu 1934 fire plow |

Reference Notes

1. Harold K. Steen, The U.S. Forest Service: A History (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1976), p. 246.

2. Ed Slusher to Henry C. Dethloff, February 6, 1988, Intaglio Collection, University of Montana Archives, Missoula, MT.

3. Missoula, MT, The Sunday Missoulian (August 18, 1940), pp. 1, 6.

4. Regional Forester Evan W. Kelley to Forest Officers, January 6, 1942, historical files, Regional Offices, Missoula, MT.

5. Press release, Region 1, #904, Missoula, MT. February 7, 1942, historical files, Regional Offices, Missoula, MT.

6. Kelley to Forest Officers, January 6, 1942, historical files, Regional Offices, Missoula, MT.

7. Steen, The U.S. Forest Service, pp. 248-249; Evan W. Kelley, Washington, D.C., to Elers Koch, Missoula, MT, March 20, 1943, historical files, Regional Offices, Missoula, MT.

8. Kelley to Koch, March 20, 1943.

9. Press release, Region 1, #905, March 7, 1942.

10. S. Webb, Acting Regional Forester, to Forest Officers, April 20, 1943, historical files, Region 1.

11. E.H. Clapp, Acting Chief, Forest Service, to the Secretary, May 23, 1942, historical files, Region 1.

12. Elers Koch, Memorandum for Mr. Webb, June 15, 1942, historical files, Region 1.

13. Philip Neff, Memorandum for Mr. Webb, June 17, 1942, historical files, Region 1.

14. Press release, Region 1, #927, January 18, 1944.

15. Press release, Region 1, #907, July 30, 1942.

16. Press release, Region 1, #913, January 26, 1943.

17. Press release, Region 1, #929, May 8, 1944

18. Press release, Region 1, #930, May 8, 1944; Lolo National Forest Inspection Report, July 26, 1944, Federal Records Center, Seattle, WA, 095-59A626; Press release, Region 1, #919, August 25, 1943; Willard R. Falls to Henry C. Dethloff, January 12, 1988, and Bob Milodragovich to Henry C. Dethloff, July 19, 1988 (Hank Viche's recommendations for Chapter 8), Intaglio Collection, University of Montana Archives.

19. Lolo National Forest Inspection Report, July 26, 1944. Press release, Region 1, July 26, 1944.

20. J.F. Hamblet, "Engineering in the Forest Service: Pierce-Musselshell Timber Access Road," Memorandum submitted by Mrs. Mary Lou Hamblet Wilson, Intaglio Collection, University of Montana Archives.

23. Evan W. Kelley, "Memorandum for the Record," October 31, 1944, Federal Records Center, Seattle, WA, 095-99-77-0315, Box 1.

24. Press release, Region 1, #947, March 19, 1945.

25. Ibid., #944, #945, February 5, 1945.

26. Press release, Region 1, #918, July 21, 1943; "Memorandum for Region One Personnel in the Regional Office, Experiment Station, Lolo Forest and the Shops" June 14, 1945, Missoula, MT. in historical files, Region 1; Memorandum, to All Federal Employees in Montana, from Helena Office of War Information, (received) March 31, 1943, in historical files, Region 1.

27. Honor Roll, World War II, historical files, Region 1.

28. Press release, Region 1, #950, June 21, 1945.

30. Press release, Region 1, #952, June 30, 1945.

31. Press release, Region 1, #953, July 2, 1945.

32. Press release, Region 1, #957, September 15, 1945.

33. Press release, Region 1, #960, January 18, 1946; #962, February 21, 1946; #963, February 25, 1946.

34. Press release, Region 1 #968, April 5, 1946; L.D. Bruesch, Memorandum, January 20, 1988, Intaglio collection, University of Montana Archives.

35. Press release, Region 1, #970, April 25, 1946.

36. History of Smokejumping, USDA Forest Service, Northern Region, Division of Fire Control, Missoula, MT (April 1, 1974), pp. 1-2.

37. Ibid., pp. 3-4; Albert N. Cochrell, A History of the Nezperce National Forest (Missoula, MT: USDA Forest Service, 1970), p. 83.

38. History of Smokejumping. pp. 5-11; Press release, Region 1, #942, December 8, 1944.

39. History of Smokejumping, pp. 12-14.

41. Press release, Region 1, #1005, July 7, 1947.

42. Press release, Region 1, #991, January 29, 1947; #992, March 1, 1947.

43. Press release, Region 1, #989, November 2, 1946; #1016, March 22, 1948; #1037, February 13, 1949.

44. Press release, Region 1, #990, November 8, 1946.

45. Press release, Region 1, #1018, April 19, 1948.

46. P.D. Hanson, "History of the Mann Gulch Fire," Helena, MT, August 5, 1949, pp. 1-7 historical files, Region 1.

49. Press release, Region 1, #1047, October 31, 1949; and see Report of the Board of Review, Mann Gulch Fire, Helena National Forest, August 5 1949, held in Missoula, MT, September 26-28, 1949, 202 pp. plus various paginations, in historical filed, Helena National Forest.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

history/chap8.htm Last Updated: 10-Sep-2008 |