|

WHEN THE MOUNTAINS ROARED Stories of the 1910 Fire |

|

History of the 1910 forest fires — Idaho & Western Montana

by Elers Koch

Introduction...

If history is not written it is soon forgotten. The 1910 forest fire in the Northern Rocky Mountain Region is an episode which has had much to do with shaping the fire policy not only of that region but the whole United States. The tragic and disastrous culmination of that battle to save the forests shocked the nation into a realization of the necessity of a better system of fire control.

It is now thirty-two years since that memorable summer. The men who took part in the campaign are getting older each year and before many more years have elapsed the 1910 fire season will be only a tradition. For this reason the writer who, as Supervisor of the Lolo Forest, had some small part in the campaign and the background of a current knowledge of the regional situation through those trying days, has undertaken to compile an informal record of the fire history of that year. This is not written for publication, but primarily as a record for the Forest Service, so that the story will not be lost.

A large mass of historical material was assembled under the direction of Mr. Fred Morrell in 1926, and free use has been made of these records.

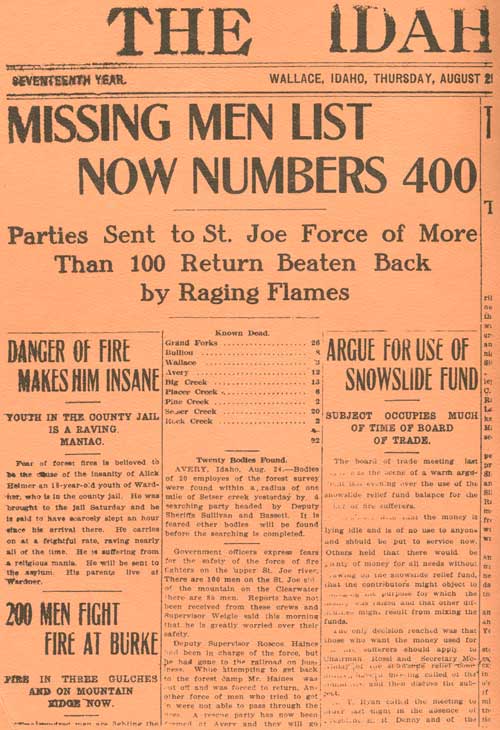

(The Idaho Press, August 25, 1910)

(click on image for a PDF version)

(The Idaho Press, August 25, 1910)

(click on image for a PDF version)

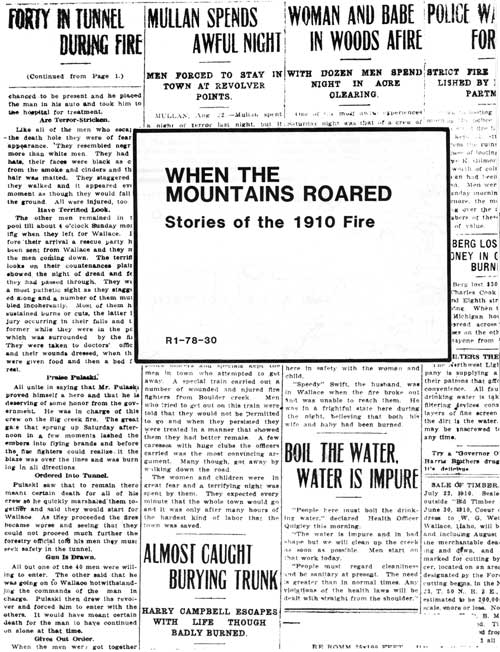

Areas effected by forest fires (1910)

(click on image for a PDF version)

The Organization of the National Forests (1910)

By 1910 the organization of the National Forests in Region One was pretty well shaken down under the direction of the Forest Service, following the transfer from the Department of the Interior in 1905.

The first Forest Reserves in the Region date back to February 22, 1897. These included the old Lewis & Clark, which took in most of what is now the Flathead and the western section of the present Lewis & Clark and Glacier National Park. The old Bitterroot Reserve, created February 22, 1897, included most of the country from the Lolo Trail south to the Salmon River and a strip in Montana on the west side of the Bitterroot. The Priest River part of the Kaniksu was set up in 1898. The next oldest Forests in the Region are the Elkhorn, now the Helena, the Absaroka, the Little Belt, now in the Lewis & Clark, the Kootenai, and the Madison, which were withdrawn from 1900 to 1902. Most of the other Forests in the Region were established 1905 to 1906, including the Lolo, Cabinet, Pend Oreille, Coeur d'Alene and St. Joe.

Some sort of primitive fire control had been established under the General Land Office on the old Lewis & Clark, Bitterroot and Priest River Forest Reserves. The country was partly explored and a few trails built, but not a great deal had been accomplished up to the general reorganization of the older units, and a new organization of the new Forests by the Forest Service in 1905 to 1907.

In 1908 the present regional organization was set up with W. B. Greeley as District Forester and F.A. Silcox as Assistant. By 1910 the organization had pretty well settled down to approximately its present form. At that time, George N. Ring was Supervisor of the Nezperce; Major F.A. Fenn had the Clearwater, which then included most of the present Clearwater and what was subsequently the Selway Forest. W.G. Weigle was Supervisor of the Coeur d'Alene, which included most of the present St. Joe. W.N. Miller had the Kaniksu, and J.E. Barton the Pend Oreille. In Western Montana the Supervisors were as follows: Kootenai, Dorr Skeels; Blackfeet, F.N. Haines; Flathead, Page S. Bunker; Cabinet, Ralph H. Bushnell; Lolo, Elers Koch; Bitterroot, W.W. White; and Missoula, D.G. Kinney.

The five or six years previous to 1910 had all been fairly favorable fire years, so that the organization on many of the Forests had relatively little experience in large-scale fire-fighting. An exception to this were the Lolo and Coeur d'Alene Forests. The year 1908 was a fairly dry year, and the C.M. & St. P. Railway was just finishing construction through these forests, and in the course of right-of-way clearing operations scattered fire pretty well all along the line, so that these forests went through a rather intensive training period and the personnel learned to handle large crews on fires. The effect of this training was very apparent in 1910.

The Great Fire

Set an airplane course from Clark Fork, Idaho, south 25 degrees east, approximately along the axis of the Bitterroot Range, and fly on this course 160 miles to Moose Creek on the Selway River. On 70 percent of this flight you would be flying over 1910 burn, with the burned area extending an average of 25 miles on either side of the line. Even then you would have seen only three-quarters of the burned area, through the South Fork and the North Fork of the Flathead, and westerly across the Kootenai and Kaniksu Forests to see the rest of the fire swept area. Three million acres of green forest burned, most of it in two terrifying days.

The snowfall in the winter of 1909 did not appear to be deficient. A cruising party on the upper St. Regis River from April 3 to the first of May found four to six feet of snow packed so hard that snowshoeing was rarely necessary. It is probable that the snowfall in the mountains was normal or above normal. But the summer drought started early all over the Region. From the first of April on, the usual spring rains were almost lacking. The hills hardly got green that spring. July followed with intense heat, and drying southwest winds from the Columbia plains. Crops burned up all over the Region. As an indication of the drought conditions, press dispatches on July 10 stated that the Northern Pacific Railway was laying off 3,000 to 4,000 men on account of crop failure along the line. The Forest became tinder-dry, ready to explode at the touch of a spark.

Already in June fires began to break out in all the Forests. Several times through July severe electric storms swept the mountains, starting new fires. The newly organized forest-protection force was thinly scattered. There were no lookouts, and detection of new fires depended on intermittent patrols. In the vast wildernesses of the St. Joe, Clearwater, Salmon and Flathead Rivers, were only a few primitive trails along the natural routes formed by the main divides and ridges. The great river canyons of the St. Joe and Clearwater were still almost inaccessible.

In the face of all these difficulties, the little force of rangers and guards struggled desperately and in many cases effectively with the constantly recurring fires. By July 15 over 3,000 men were employed as fire-fighters. Men were shipped from Missoula, Spokane and Butte until the supply of floating labor was exhausted.

There was no reserve of fire equipment in the Region at that time. As new crews were put out, new equipment was purchased from the hardware stores. Axes, mattocks, shovels, cross cut saws, wash boilers, tubs, coffee pots, and frying pans were bought as needed until the supply in most of the local stores was exhausted. The standard bed for a firefighter that year was only a shoddy blanket or one cheap soogan.

A 50-man crew was a big one. There was no thought of putting 500 or 600 men on a fire as is frequently done today. Firefighting methods used were not fundamentally different from present practice and a great deal of efficient work was done. By August 15 over 3,000 small fires and over 90 large ones had been controlled. In the more accessible areas such as the Lolo and much of the Coeur d'Alene Forest, a real and successful attempt was made to send crews promptly to all fires. In the back-country districts of the Clearwater, Selway and Flathead Rivers, there is no doubt that many fires burned for weeks without being attacked, and in many cases five or ten men were fighting fires which would require a hundred to do effective work.

On August 8, President Taft authorized the use of the regular Army for firefighting. About eight or ten companies were assigned to Region One, on the Coeur d'Alene, Lolo and Flathead Forests. Since most of them got in place just about the time of the big blow-up, their accomplishment was not important, though they were of some value for police purposes during the general disorganization after the big fire. The firefighting job progressed with varying degrees of success through July.

Severe electric storms swept the mountains in the latter part of July and many new fires were started. By the end of the first week in August things began to look better. On the 9th, the Supervisor of the Lolo, whose forest had been particularly hard hit, made the statement to the press that every fire on his Forest was out, or practically under control. Regional Forester Greeley asserted on that date that the general situation was greatly improved.

The 10th of August was a bad day, with low humidity and high winds. Fires picked up everywhere and there was a wave of fire which crossed the Bitterroot range from Idaho into Montana in many places all the way from Stevens Peak to the Lolo Pass.

The effect of this blow-up, which greatly extended the fire lines and scattered fire widely, had much influence on the holocaust yet to come. Firefighting efforts were redoubled and more crews put out, and by August 19 things again looked better. Many miles of fire line were held, and with the end of the season approaching, it looked as though the loss might not be too great.

Then came the fateful 20th of August. For two days the wind blew a gale from the southwest. All along the line, from north of the Canadian boundary south to the Salmon, the gale blew. Little fires picked up into big ones. Fire lines which had been held for days melted away under the fierce blast. The sky turned a ghastly yellow, and at four o'clock it was black dark ahead of the advancing flames. One observer said the air felt electric, as though the whole world was ready to go up on spontaneous combustion. The heat of the fire and the great masses of flaming gas created great whirlwinds which mowed down swaths of trees in advance of the flames, In those terrible days many fires swept thirty to fifty miles across mountain ranges and rivers.

The town of Wallace lay directly in the path of the fire, and by the evening of the 20th a third of the town lay in ashes. The flames from the Coeur d'Alene fires swept on to Taft, Saltese, DeBorgia, Haugan, crossed the high range to the Clark Fork, jumped the Clark Fork, and swept on across still another range to the head of the Fisher River, destroying towns, homesteads, lumber camps, everything in their path.

Special trains, crowded with refugees, bore thousands of people to safety into Missoula and Spokane. Had it not been for fine work on the part of train crews, the loss of life would have been far greater.

The unfortunate firefighters on the Coeur d'Alene Forest were caught in the uprush of the fires from the St. Joe River across the summit of the Bitterroot Range. Too late to escape to safety, they were forced to weather the blast in such places as promised some degree of safety. Some retreated into mine tunnels, some took refuge on recently burned-over areas, some lay in small streams with their heads covered with blankets.

When the terrible toll of losses was finally added up, 72 firefighters were dead on the Coeur d'Alene Forest, four on the Cabinet, and two on the Pend Oreille. Two lives were lost in the burning of Wallace and one at Taft. A peg-leg prospector was burned near the St. Joe-Cedar Creek Divide, and three homesteaders burned to death near Newport. Altogether, 85 lives were lost in the two-day conflagration. Many of the surviving firefighters were terribly burned, and as the pitiful remnants of the crews straggled out of the mountains, the hospitals of Wallace were filled with injured men. The fires swept fiercely on all day the 20th and 21st, but about 1:00 a.m. on the 22nd, a rather sudden change in wind and humidity occurred. Fires made little advance through the 22nd and 23rd, and the night of the 23rd a general light rain, with snow on some of the higher ranges, temporarily checked the flames.

The following week burning conditions again picked up, and the widespread fires made some advance. Most of the fire crews had been driven out of the hills. Camps and equipment had burned, and crews had been largely paid off. But under the spur of District Forester Greeley crews were again organized on a large scale, and set about cutting off the spread of fires and opening up trails through the burned country. A good general rain beginning the night of August 31 ended the fire season.

The Coeur d'Alene & St. Joe

In 1910, the territory now in the Coeur d'Alene and St. Joe Forests was under direction of Supervisor W. G. Weigle, with headquarters at Wallace. Owing to proximity to settlements and the large number of fire crews out at the time of the big blow-up, the Coeur d'Alene suffered more in loss of life and property than any other Forest.

Through May, June, and the first half of July, numerous fires were started from lightning, campers, and from the two railroads which traversed the Forest. Most of these were put under control. Outside the Forest, the Pine Creek fire to the west, burned all through the latter part of July and was a continued threat. On July 23, a severe electric storm passed over, and set numerous fires. These were manned as rapidly as possible but, with new fires starting daily and continued high winds which threw brands to a great distance, conditions got steadily worse. On August 13, even though the nearest fire was six miles from Wallace, numerous pieces of burning bark as large as a man's hand fell in the streets, setting awnings on fire in three different cases. By this time there were eighteen hundred men fighting fire on the Coeur d'Alene, besides two companies of soldiers.

| omitted from the online edition |

| After the fire of August 20, 1910. (The Oregon-Washington Railroad and Navigation Depot) Wallace, Idaho. (Barnard-Stockbridge Collection, Courtesy University of Idaho Lbrary and Department of Special Collections and Archives) |

| omitted from the online edition |

| Soldier's Camp-Wallace, Idaho (1910). (Barnard-Stockbridge Collection, Courtesy University of Idaho Lbrary and Department of Special Collections and Archives) |

Wallace burns

With Pine Creek ten or twelve miles west of the city, afire all through the latter part of July and the first of August, and with numerous fires to the south, just across the St. Joe divide, the people of Wallace were badly worried. On August 14, a newspaper reporter stated that all insurance men had all their clerks busy writing fire insurance policies, but were not refusing any business.

On August 20, a high wind arose about noon. All existing fires flared up, and new ones were started. Great thunderheads showed to the south and west, as the fires rushed to uncontrollable proportions. It was obvious that a holocaust was impending.

Since the greatest danger to Wallace was from fire coming down Placer Creek, Supervisor Weigle took a saddle horse and started up the creek to reconnoiter. He was caught in the rush of the fire, and had to abandon the horse and take refuge in a mine tunnel. He did not succeed in getting back to Wallace until 10:30 that night, with his eyebrows and clothes scorched from his close encounter with the flames.

With the adjacent hillsides all ablaze, the fire broke into town at 9:15 Saturday night. The whole eastern part of the city burned, and before the flames were under control by the fire department, approximately one hundred buildings were burned, with an estimated loss of one million dollars. Two lives were lost in the fire.

A relief train on the Northern Pacific started from Wallace about 10:00 p.m., loaded with women and children. They picked up many more refugees at Mullan and Saltese, and arrived in Missoula Sunday morning. All day Sunday new reports of terrible loss of life came in, as the scorched and burned survivors of various firefighting crews stumbled wearily into town, with tales of terror and disaster.

The terrific uprush of fire from the St. Joe drainage across the divide caught every firefighting crew in that territory, and they were doomed unless they could find a safe place to weather the blast of flame. The story of each of the seven Coeur d'Alene crews caught in the fire is taken from Supervisor Weigle's report of June 24, 1911.

| omitted from the online edition |

| Wallace, Idaho— Taken before the fires of August 20. (Barnard-Stockbridge Collection, Courtesy University of Idaho Lbrary and Department of Special Collections and Archives) |

| omitted from the online edition |

| Wallace, Idaho— Taken September 12, 1910— Damage caused by the fires. (Barnard-Stockbridge Collection, Courtesy University of Idaho Lbrary and Department of Special Collections and Archives) |

Stories of firefighting crews

Pulaski's Crew — Placer Creek

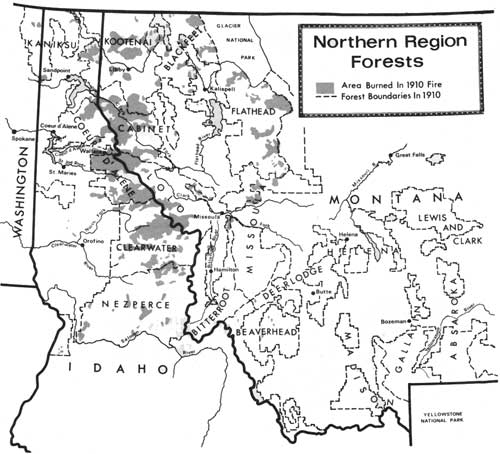

"Mr. Pulaski, who is about forty years of age, is a man of most excellent judgment, conservative, thoroughly acquainted with the Region, having prospected throughout the burned area during the last 25 years, and is considered by the old timers in the region as one of the best and safest men that could have been placed in charge of a crew of men in the hills. Mr. Pulaski was in charge of about 150 men distributed over a distance of several miles along the divide between Big Creek and the Coeur d'Alene River and Big Creek of the St. Joe River. When the danger conditions became imminent he rounded up about 40 of his men who were in the danger zone and cut off from safety on the west side of the fire where the other men were located and started with them down the mountain toward Wallace, a distance of ten miles. When he got about half way, however, he found that he was cut off by new fires. At the sight of this, his men became panic stricken, but he assured them that he would still get them to a place of safety. Being thoroughly familiar with the region he knew of two prospect tunnels nearby, the shorter being about 50 feet in length and the longer about one hundred feet in length. Not being certain as to whether or not he could reach the largest and safest, by putting a wet gunny sack over his head, he penetrated the dense smoke to where he could see the largest tunnel, and finding it was safe he rushed back to his men and hurried them to the tunnel, getting them there just in time to get them inside before the fire reached them. The portion of his crew with him consisted of 42 men and two horses. He got all of his men and horses inside the tunnel, with the exception of one man who had fallen a few hundred feet behind and was caught by the fire before he could reach the tunnel.

|

| Mine tunnel where Pulaski and crew held up until the fire passed. (Courestsy of USDA, Forest Service, Idaho Panhandle National Forests) |

"The intense heat caused by the forest fire outside of the tunnel caused the cold air of the tunnel to rush out and the smoke and hot air to rush in. The timbers supporting the tunnel caught fire and Pulaski stood as near to the mouth of the tunnel as he could, and from a little stream that flowed from the bottom of the tunnel dipped water with his hat to dash upon the burning timbers, until he was badly burned and fell unconscious. Prior to becoming unconscious himself, he had commanded all his men to lie on their faces for protection. All of the men were evidently unconscious for a portion of the time. One of the men, however, having sustained less injury than the others, recovered to the extent that he was able to crawl out of the tunnel, and the fires by this time had subsided sufficiently for him to drag himself into Wallace and notify the Forest Office. This was about 3:00 in the morning. A crew was immediately sent to the tunnel and all of the men and horses were removed. Although nearly all of the 42 men were still in a helpless condition after being taken to the hospital in Wallace, they rapidly recovered their strength, with the exception of five who had smothered before they were reached. The two horses, although still living, were in such bad condition that they were immediately shot. The man who failed to get into the tunnel was burned beyond recognition. Had not Pulaski known the location of this tunnel, every one of the 42 men in his crew would have perished."

Bell's Crew — Middle Fork Big Creek

"Mr. John W. Bell is a man of about 35 years of age, thoroughly acquainted with mountain conditions, having spent a large part of his life in this western country. He is a conservative and thoughtful and an all-around man of the mountains. He had his crew, consisting of about 50 men, working in conjunction with Pulaski's crew at the head of the middle fork of Big Creek. When the terrific windstorm arose and fires were started in new places, he sought safety on a small clearing on the homestead claim of Joseph Beauchamp. Under ordinary conditions this place, consisting of a clearing of about two acres, would have been sufficient to offer protection. A small stream flowed through the opening and some of the men protected themselves by lying down in the stream, while seven sought shelter in a small cave that had been dug for the purpose of storing the belongings of Mr. Beauchamp. The terrific storm that preceded the fire by about a minute, which was of course intensified by the fire, overturned and broke off practically every tree of a dense forest in this region. The seven men who sought shelter in the cave were burned beyond recognition and three others who were in the stream were killed by falling trees. This constituted the number of dead of this crew, but the remainder who sought shelter in the creek had their hair burned off the back part of their heads and the skin all burned from their necks, besides being nearly suffocated from the smoke. One of these injured men made his way into Wallace, a distance of twelve miles, by nine o'clock Sunday morning, the day after they were injured. Judging from the distress of the men in Pulaski's crew, I had already put a crew of 17 men to work cutting out a trail leading to this point, and upon learning the condition of the men, I immediately sent out two doctors on foot, with a crew of men with medicine, blankets and provisions, to help the injured men. It required a crew of 17 men working all day Sunday, Sunday night, Monday and Monday night to open the trail to the injured men 12 miles from Wallace. This enabled me to get pack horses in to the injured men and they were brought to Wallace. With the exception of two men who had friends at this place, the dead men were buried near the spot where they died, a few days later. Reverend Carter, a Congregational minister at Wallace, volunteered to go along with the burial crew to give Christian burial to the dead. All of this crew, with the exception of the ten men who were killed, speedily recovered from their injuries at the hospital at Wallace. The Beauchamp cabin was located in the Middle Fork of Big Creek in Section 27, Township 47 North, Range 3 East."

Rock's Crew — Setzer Creek

"Mr. William H. Rock is a man about 25 years of age, having served for two years in the region in which he was fighting fire; therefore he was thoroughly acquainted with the details of the region where his men were working. He had a crew of approximately 70 men about six miles northeast of Avery, Idaho. When the terrific windstorm arose and the fires started up in many places he found he was cut off from getting his men out to Avery. Therefore he led them to an area that had burned over the day before. This proved to be a place of absolute safety and all the men came out uninjured. As evening drew on the fires were burning up so terrifically that huge columns of smoke which contained large quantities of combustible materials would frequently burst into flames that would shoot into the sky for thousands of feet. This, some of the men told me later, frightened Oscar Weigert to the extent of his wanting to kill himself. He left the crew, however, without anyone knowing it at the time, and even though two shots were heard, no one knew that he had taken his life until the following morning. Mr. Rock had his crew in perfect safety, and the unfortunate happening to Mr. Weigert was a matter entirely beyond the control of Mr. Rock who was in charge. The location of Weigert's death was somewhere on the ridge on the east side of Setzer Creek."

Debbitt's Crew — Setzer Creek

"Mr. Debbitt is about 35 years of age. He was in charge of the district during the last four years, having headquarters within six miles of where the men perished; therefore was thoroughly acquainted with all the conditions which might have led to the protection of the men. Owing to the fact that he had general charge of the district, he was away from the men when they perished, but a few hours preceding this, seeing that danger was imminent, he sent Charles Sullivan, who was then serving as Deputy Sheriff at Avery, into where about 70 men were working on Setzer Creek, telling them to come out to Avery immediately as there was danger of being hemmed in by the fire. All of these men came out with the exception of 28 who thought there was no danger and refused to come. All of these 28 were burned beyond recognition a few hours afterward. These men were all wrapped in blankets and sewed in heavy canvas and buried where they were burned. The bodies of the men were found at the extreme head of Storm Creek; the next drainage west of Setzer Creek in Section 29, Township 29 North, Range 5 East."

Hollingshead's Crew — West Fork Big Creek

"Mr. Hollingshead is about 22 years of age. Although a young man, he has always exercised good judgment.

He is conservative and had served as Forest Guard in the immediate region in which he had charge of men for two years; therefore was thoroughly familiar with the country. He had charge of a crew on the west fork of Big Creek fighting a fire that was coming northeast from Trout Creek. He had a crew of about 60 men. When the terrific winds scattered the fires all over the region and they discovered that they were surrounded by fire, all of his men with the exception of 19 worked through the fire line to a place of safety on an area that had previously burned over. Nineteen of these men, being thoroughly panic stricken rushed down the hill ahead of the fire to a little cabin where five pack horses were stationed. They found that the fire was all around them. They went into the cabin and remained there until the roof began falling in. They rushed out of this and tried to break through the fire line, but the fire was so terrific that 18 out of the 19 perished in the flames within a few feet of the cabin. The nineteenth man accidentally worked his way through the fire line and came out to the St. Joe two days later with all the skin off his face and hands and his clothing practically burned from his body. After six weeks in the hospital this man fully recovered. Mr. Hollingshead the next day went into the place where these men perished and found eighteen men, five horses and a large black bear that had perished in the flames all at the same place. The men were wrapped in blankets and canvas and were buried where they perished. They were all burned beyond recognition. The cabin where these men perished was known as the Henry Dittman cabin, and located on a tributary of Big Creek, known as Deadman Gulch near the south line of Section 35, Township 47 North, Range 2 East."

Danielson's Crew — Stevens Peak

"James Danielson is a young man about twenty-two years old. Although young he was thoroughly acquainted with woods work and had been over the Region many times where his crew was located. He had eighteen men in his crew. When he found he was surrounded by fire he took his men to an open park near the timber line which contained a light covering of bear grass. They burned off a large area in this park, thinking that by so doing they would have absolute protection, and the general appearance would indicate that they did have protection of the very best kind. When the terrific fires approached this area, however, instead of stopping when the burned area was reached, as would be expected, they continued to burn over the same area the second time. The men in Danielson's charge had their blankets with them which served as their only protection. They held these blankets over their heads until the flames had practically consumed them. One of the men, however, by accident, inhaled the flames and perished on the spot. The other men were very badly burned about the face and hands. The fire reached these men about nine o'clock Saturday evening. Early Sunday morning Mr. Danielson, although badly injured, worked his way into Mullan, a distance of five miles, and delivered the news. Pack horses were immediately sent to the place and the men, although badly injured were brought to Mullan and given medical attention at Dr. Key's office before they were brought to Wallace at 2:00 p.m. by special train which I received through the kindness of the Northern Pacific Railway Company. These men were all placed in the Wallace hospital, where they remained from one to six weeks, and all recovered with the exception of three who have stiff hands."

Taylor's Crew — Bullion Mine

"S. M. Taylor is a man of about forty years of age and a conservative, intelligent fellow, thoroughly able to handle men, and a prospector in this region for many years. He had charge of the Bullion fire along the Montana-Idaho line east of Wallace. When Mr. Taylor discovered that he was surrounded by fires he took his crew, consisting of about sixty men, to the tunnel of the Bullion mine, which seemed to Mr. Taylor to offer absolute protection. One of the men, Mr. Ryson, who was with the crew, knew the tunnel thoroughly, owing to the fact that he had made it. Most of the crew who went into the tunnel passed an overhead air shaft. Eight of the men, however, did not do this and the smoke rushed in to where these eight men were located and suffocated them. The remaining crew came out a few hours afterward without any injury; neither had they experienced any inconvenience during the time they were in the tunnel. Mr. Taylor immediately notified me of the conditions and although this was within about four miles of the Northern Pacific Railway, several large trestles along the mountain had burned out; therefore I could not depend wholly upon the railroad to bring these dead men to Wallace, so I sent a crew of men the next day to bury the dead bodies. About ten days later, when the railroad was sufficiently repaired on both sides of the mountain to make it more convenient for handling these bodies, I sent a crew of men to the place with pack horses to disinter the bodies and bring them to the railroad, where through the kindness of the Northern Pacific Railway Company, a special car brought them across the mountain to Dorsey. At this point a trestle was still not replaced and the dead bodies were transferred to another special train sent out from Wallace. The bodies were delivered at the morgue at Wallace and prepared for burial and a few days later they were given Christian burial in the Wallace cemetery."

Joe Halm's Crew — St. Joe River

"For nearly a week after the great fire, it was believed that Ranger Joe Halm had perished with his crew of sixteen men. Halm had gone back into the St. Joe wilderness, 65 miles across the Bitterroot range to fight the Bean Creek fire. On the 20th when the great wind swept the country, the crew was surrounded by fire and forced to take refuge on a sand bar in the St. Joe River near the mouth of Bean Creek. Here they weathered the fire, which swept the entire upper St. Joe drainage. The story of the party has been well told in an article by Halm in the July 1930 issue of 'American Forests and Forest Life.'

"Their two packers fled across the range just ahead of the flames, taking only one horse with them. The entire pack train had to be abandoned and all of the horses were burned.

"It was not till a week later that Deputy Supervisor Roscoe Haines, coming to the rescue of the party from Iron Mountain, located the crew and brought word of their safety."

The Milwaukee Railroad

At the time of the great fire, the C.M. & St. P. Railroad had just been opened through the St. Joe territory. While trains were running, the many high timber bridges had not yet been filled, and there was much construction work still underway. The whole twenty-five miles of railroad through the rugged country between Avery and the Taft Tunnel was swept by a consuming blast of fire, so hot that pick handles lying in the open beside the track were utterly consumed. Considering the number of people in this section and the severity of the fire, it is almost miraculous that no lives were lost along the railroad. Great credit is due C. H. Marshall, superintendent, and W. R. Lanning, chief carpenter, of the Missoula division. Under direction of these men the town of Avery was evacuated by special train. Between Avery and the Taft Tunnel there were probably 1,000 people, mainly railway workers and their wives and children. These were picked up by work trains at the last moment, with bridges blazing, and at imminent danger to the train men's lives. Trains were run into tunnels and held there while the fire swept by, consuming everything up to the tunnel portals. Sixteen bridges, from 120 to 775 feet in length, were burned in this section.

|

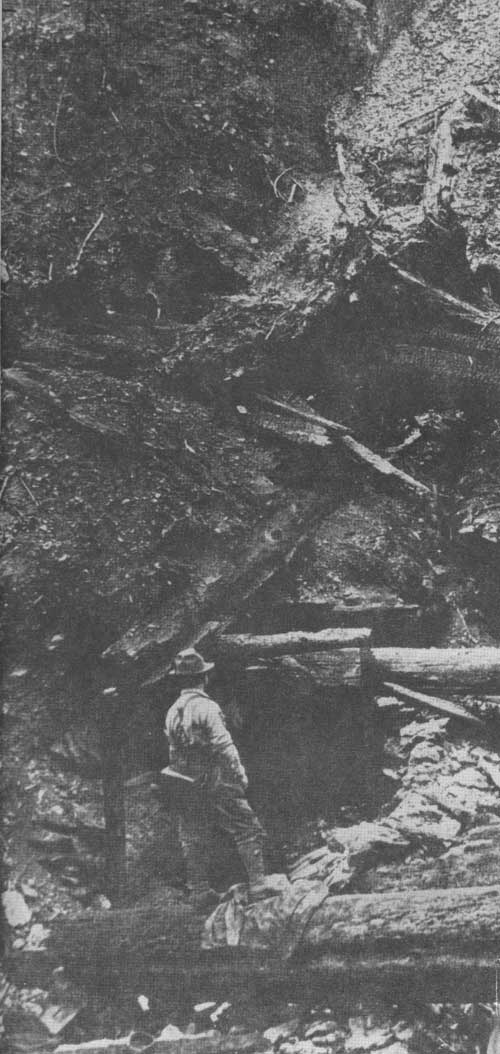

| Placer Creek. (Courestsy of USDA, Forest Service, Idaho Panhandle National Forests) |

Individual Experiences...

Considering the number of people, miners, homesteaders, etc., scattered through the mountains, it is remarkable that there was not greater loss of life. Several parties had very narrow escapes. While Wallace was burning, Mrs. "Speedy" Swift, with her baby, was hemmed in by the fire at the Hord Ranch on Placer Creek, four miles from Wallace, together with a dozen firefighters. They battled the fire all through the night with wet gunny sacks over their heads. The house was saved, but all other buildings burned, and it was not until the next morning that her husband, who was in Wallace, learned of his wife's survival.

The Pattison party, consisting of Mr. and Mrs. E. H. Pattison of Wallace and five other men, had an extremely narrow escape. They were working on a mine on Sherlock Creek near the head of the St. Joe River when the conflagration of the 20th struck them. When the tornado of fire and wind swept around them, they were able by great good fortune to get through a line of the fire to a freshly burned area where they weathered the storm. Scorched and half-blinded by the smoke, they made their way the next day thirty miles down Cedar Creek to Iron Mountain, Montana. One member of the party, Con Roberts, a prospector with a wooden leg, got separated from the party in the smoke and flame. His body was found about a week later, half consumed.

Mr. and Mrs. George Cook, Mullan, Idaho, were working at the Silver Cable mine near the head of the St. Regis River. When the uprush of the fire struck them on the 20th, they were forced to flee across a high divide and down Prospect Creek 30 miles to Thompson Falls. Miraculously, they made it, through fire and smoke. Fortunately the fire lagged somewhat on the creek bottom, and though it swept clear ahead of them on both sides of Prospect Creek, by walking all night and the next day, the exhaused couple reached safety.

Several parties of miners, caught in the conflagration, managed to survive by retreating to mine tunnels.

| omitted from the online edition |

| Coeur d' Alene Hardware Warehouse ruins after the August 20 fire. (Wallace, Idaho). (Barnard-Stockbridge Collection, Courtesy University of Idaho Lbrary and Department of Special Collections and Archives) |

| omitted from the online edition |

| Store ruins (Wallace, Idaho). (Barnard-Stockbridge Collection, Courtesy University of Idaho Lbrary and Department of Special Collections and Archives) |

Burying the dead& Payment of claims

Owing to the great difficulties of transportation, most of the dead fire-fighters' bodies were buried where they lay. A great many of them were burned beyond all hope of identification. The eight dead men at the Bullion mine were temporarily buried in a long trench, but a week or ten days later were disinterred and the bodies moved to the Wallace cemetery.

Most of the other bodies lay in the temporary graves until 1912, when fifty-three corpses were exhumed under contract with a local undertaker, at a cost of $60.15 each, and reburied in the cemetery at St. Maries. In 1924 the appropriation bill carried an item of $500 for marking the graves, and a suitable monument and headstones were erected.

(Spokesman Review, August 25, 1910; The Idaho Press, August 25, 1910)

(click on image for a PDF version)

(Spokesman Review, August 25, 1910)

(click on image for a PDF version)

The treatment of the injured men immediately after the fire presented many difficulties. Some of the survivors were terribly burned, and most of them suffering from eye or lung damage from the smoke. The records show that 101 men were given hospital treatment on the Coeur d'Alene Forest.

Fiscal difficulties and lack of legal authorization and appropriations created great difficulty in caring for the injured men. A fund of $1,700 was raised by contributions from the Forest Service personnel, and $1,000 was contributed by the Red Cross, which met most immediate needs.

The present Employee's Compensation Act did not exist at the time, but Congress finally passed a general deficiency item to cover cost of hospitalization and compensation to injured men and the families of men who were killed. Since, with the exception of a few local men, most of the firefighters were transients unknown even to each other, and some of the time books were burned, the task of final settlement with the men, and identification and location of their families, was an enormous one, involving in several cases the location of relatives in European countries, and a vast amount of correspondence.

Lolo Forest

The Lolo Forest fought one long battle against fire from the latter part of June to the end of August. The organization had not only its own territory to protect, but was threatened by a continuous series of fires coming up from the Idaho side of the Bitterroot range from the wilderness country of the St. Joe and Clearwater, all the way from Stevens Peak to Lolo Pass. Most of the loss suffered in the Lolo was from the sweep of fire from Idaho on August 20 and 21.

Throughout July and the first part of August there was a series of fires, believed to be incendiary, extending from Frenchtown up the Nine Mile Valley. Ranger D. B. McGregor put up a fine fight on these fires, but as soon as one fire was beaten, another would be started, mostly in the slashings of the Western Lumber Company.

Five or six large fires were handled in succession, but one by one they were beaten, and when the big wind of August 20 arrived, the lines all held, and the Nine Mile Valley was saved.

In the meantime, the Lolo Rangers were carrying the fight over into Idaho. Ranger T. C. Spaulding took a big crew across Lolo Pass to the Lochsa country. Kenneth Robinson had a crew at the head of Fish Creek. Ranger H. P. Barringer of the Lolo and Ranger J. S. Garrison of the Clearwater fought a long battle on fires coming up opposite the head of Trout Creek. Ranger F. Haun at Saltese, with fine assistance from Ranger R. A. Phillips and Ranger J. E. Breen, did a splendid job of organization against the many fires threatening the upper St. Regis country. It is almost miraculous that, with the many fire crews strung along the summit of the Bitterroot Range, when the big fire hit them, not a man or a horse was lost from the Lolo fire crew.

When the fire swept across the St. Regis drainage on August 20 and 21, the towns of Taft, Haugan and DeBorgia were completely destroyed. Saltese was saved, except for one or two buildings, by a fine battle led by Ranger Haun and the Northern Pacific Railway crew. Haun tells of one man burned to death here. The man had been badly burned at Taft, and Haun and Breen had brought him down to Saltese, where he was put in a freight car, his burns dressed with oil and cotton. One of the man's friends, having done his best to salvage the whiskey supplies in Saltese before they burned, looked in to see how the man was doing and lit a match for illumination. The unfortunate man's cotton dressings were ignited and he rushed forth screaming, and burned to death.

Roy A. Phillips' Story

Forest Supervisor R. A. Phillips was at that time a ranger under F. D. Haun. He was handling speeder patrol along the railroad track between Saltese and Lookout and when fires commenced to break in all directions he was put in charge of one side of the Bullion Mine fire. His own story of the big fire is well worth quoting.

"On August 20, I had completed a fire line to the state line and my crew had been reduced to a patrol basis. Baird had a crew on the south side of the fire and was having some trouble holding his line. S. M. Taylor, foreman for the Bullion crew, and now county commissioner of Shoshone County, had all but about a mile or mile and a half of the west side of the fire trenched. I had been around the fire a day or two previously and it was apparently in good shape and not a great deal of line was being lost. The fire had, of course, been projected by this time and J. E. Breen, Ranger, stationed at Taft, was in charge.

"The day of August 20 differed very little from preceding days, there was little wind noticeable and there was no premonition of the calamity about to occur. My crew had a hard job holding a section of line under the fire on a precipitous slope and it took us until dark to get everything in good shape to leave for the night. Even in those days we had discovered the futility of leaving out night patrolmen except in extreme instances and I took all my crew into camp that night, which proved to be a very fortunate circumstance. As we had no lanterns or other means of light, I recollect that it was so dark that we could only follow the fire line with difficulty, one man getting lost in the brush and it was some job to get him back on the line.

"About nine-thirty, while we were on our way into camp, we were startled by a burning brand apparently a couple of feet long that hurtled down out of the sky a hundred yards from the camp. I sent two men from the camp to locate this phenomenon and hastily got something to eat and went to bed, dog tired.

"At midnight, or shortly after, the night cook woke me up probably alarmed by the noise that the relief train from Wallace was making on its way east — the engineer was blowing the whistle intermittently to warn people to be ready to leave. However, the train did not wait for us, although there were in the neighborhood of 150 men in camp. By this time the flames were beginning to show on the horizon and the roar of the fire was becoming audible. I speedily awakened several men I knew were dependable and went over to the point on the railroad where our supplies were unloaded, to take care of some provisions unloaded late the previous afternoon. We accomplished our object and were returning to the camp with four or five water barrels that the railroad company had sent out for use on bridges, when we met the entire crew badly demoralized, and apparently leaving the country. The fire by this time was an awe-inspiring spectacle, the whole horizon to the west was aflame and the noise caused by the falling timber was terrific. In addition, our fire was out of control and raging across the lines below us to the southeast and our only avenue of escape effectually cut off.

"The entire fire crew lead by one of the foremen, had conceived the idea of getting into a railroad tunnel at Borax as they thought it was the safest place to escape the fire. Knowing from experience gained traveling through this tunnel on patrol that there was always a strong air current through it, I succeeded in turning back all of the crew but the foreman and one other man and, finding that they were alone, they soon followed us back to the campground. On the way we met Lieut. Titus who had arrived in camp the previous afternoon with a detachment of regular soldiers for the purpose of patrolling the fire lines. He and his men were following up the fire fighters as they had no intention of remaining in camp alone. The lieutenant was agreeable to the plan I suggested of remaining where we were, so we returned to camp and speedily constructed a fire line around it and immediately set a backfire which spread rapidly outward drawn by the suction of the main fire.

"By this time the roar of the oncoming fire was so great that it was only with difficulty that conversation could be carried on without a person standing at your side. The vanguard of the fire was sweeping over us and the hills all around us were catching fire and soon were a raging mass of flames. Our backfire had burned out perhaps one or two hundred yards before the main front of the fire struck and when they came together the heated air current filled with cinders swirled down upon us and for a short space of time that seemed an eternity, we gasped and choked for air and were blinded by smoke. Finally the air cleared and we found that nearly everything inside our fire line was burning that had not been wet down; fortunately the ground was fairly clear of refuse and the buildings and tents had all been soaked with water and did not catch fire.

"Outside of a few men who were temporarily blinded by smoke, the crew was in fairly good shape. One man who thought he had gone blind was thwarted in an attempt to take his life. We were also fortunate in having a week's supply of provisions ahead. Everyone was so nearly exhausted and weak from the effects of the smoke to be much concerned about anything the first day, and although an attempt was made to get through to the other crews, the ground was still too hot to do so. However, a timekeeper with the Bullion crew managed to get through with the news that eight of the men in that crew had perished in the Bullion tunnel. I attempted to get through to Saltese with this message and met J. E. Breen coming up on a speeder so returned to camp while Breen went back to Saltese to report. The fire was still burning briskly along the railroad and the chance for suffocation was considerable as it was impossible to tell what one was running into as in places the flames were shooting across the rails and the smoke was blinding. However, I succeeded in getting back to camp and the following day Lieut. Titus, John Baird, and I went into the Bullion mine, identified the bodies there, wrapped them in blankets and interred them in a long shallow trench, side by side.

Several days later Baird and I disinterred three of the bodies, lashed them on horses and took them over to Potsville where we turned them over to a troop of soldiers to take into Wallace. These men were Larry Ryson, a Wallace miner, and two young men, Leslie Zellers and Val Nicholson from Kellogg. The remaining bodies were disinterred a week or ten days later, when the railroad resumed operations.

"The story of the experience of the men in the Bullion tunnel is worth recounting. Their first knowledge of the fire came when a section of a limb of a tree as big as a man's forearm fell out of the air, striking a sleeping man on the leg, causing a serious bruise. On awakening, this man perceived the fire coming up Bullion Creek although it was only a short distance from the camp. One member of the crew carried his blankets into the tunnel and it was only through this circumstance that any of the crew was saved. These blankets were stretched across the face of a little drift running off from the main tunnel and all but eight men went into this drift. The other eight men apparently dropped in their tracks and from all appearances, died instantly without any agony or suffering. Of the men in the drift, several were suffering from the effects of smoke and bad air, but there were no casualties.

"The spectacle of this fire was awe-inspiring almost beyond belief and was sufficient to strike terror to the strongest heart; it seemed a hopeless task to attempt anything that would divert the path of so ruthless a monster; many grown men in the crew were absolutely helpless and there were several who could only weep or moan, believing they were doomed. The fact that we were situated on a small knoll fairly clear and sufficiently elevated to alleviate the danger of suffocation, and the fact that our backfire spread so rapidly accounts, I believe, for our pulling through. The water in the stream below us became almost boiling hot and was, I judge, too hot to be borne had it been necessary to take the water. A dense stand of timber a short way from our camp was laid flat to the ground and in places large trees were lifted bodily out of the ground and deposited some little distance from where they originally stood.

"Our backfire was responsible for breaking the fury of the main front of the fire and a considerable area back of our camp and in line with the direction of the fire was merely spotted with fire. In this area at daybreak we discovered that there were eight or ten head of deer that showed no signs of fear on approach. They remained around camp until the ashes had cooled.

"On the next day following the fire, we took steps to save a railroad bridge and tunnel which were temporarily saved by our backfire but which would undoubtedly have burned had we not put out the fires that still burned near them."

Cabinet National Forest

The Cabinet Forest suffered a tremendous loss from fire in 1910, but the greater part of the damage was done in two days when the fires from the St. Joe and Clearwater swept across the high divide, clear across the Clark Fork valley, and beyond to the Kootenai Forest. There were at least three large fires which came across the divide. The great St. Joe fire, which burned Wallace and DeBorgia, crossed the range and threw a long spur south of Prospect Creek clear to the Clark Fork River. Two fires swept out of the North Fork of the Coeur d'Alene, one from Trail Creek and one from the extreme head of the river. Both these fires crossed the Clark Fork valley, destroying homesteads, towns and sawmills.

The railroad station at Tuscor was burned, and Ed Donlan lost his mill at Trout Creek, with most of his equipment, including 25 head of horses, the pigs in the pen and 13 million feet of white pine lumber. Many ranches were burned.

Four firefighters lost their lives on Swamp Creek. The following story is quoted from the official report:

Tuscor Fire

"H. S. Kaufman, Forest Ranger, in charge. Roy Engle of Noxon, Montana, was directly in charge of the party in which loss of life occurred.

"For several days before August 21, 1910, Roy Engle was working on Swamp Creek on what was known as the Swamp Creek division of the Tuscor fire. His crew was composed of about 25 men. On August 21 this crew was working up Swamp Creek about 10 to 12 miles from its mouth. Ranger Kaufman, who was in charge of the fire, was working with a crew along Clark Fork River at the mouth of Swamp Creek. In the afternoon of August 10, a strong wind sprang up and scattered the fires in all directions. Realizing the dangerous position of Engle's crew, Ranger Kaufman sent a messenger to Engle, directing him to come out at once with his crew. Engle got this word late at night August 20 and started out in the morning of August 21, following the trail down Swamp Creek. Getting down within four miles of the river, they met a fire coming up Swamp Creek. This was a fire which had come ever the divide from Idaho the previous night and was, up to this time, entirely separate from the fire on which the crew was working. When Engle with his crew met this fire it was too large to pass through so Engle took his crew back up Swamp Creek from whence he had come, expecting to cross over the burned area through the fire on which he had been working, but on reaching a point where he had expected to pass through the fire line, he found that the wind had fanned the fire into a raging furnace. Finding that they were cut off from the valley, Engle took his crew on farther up Swamp Creek hoping to reach a large body of slide rock located there. They were soon overtaken by the fire coming up the creek, and made a stand on an open slide rock side hill, several of the party digging holes in the slide rock for further protection. The fire swept up the gulch and side hill, a top fire burning everything in its path and throwing embers among the men who were making their stand on the slide rock. Five of them became panic-stricken and left the crew starting up the mountain out of the slide rock. Anderson was behind, and when the other four were caught by the fire he abandoned the attempt to escape and came back to the crew badly but not fatally burned. The other four men perished when the fire strick them. Several other members of the crew were more or less burned and all of them were nearly blind from smoke and heat.

"The men were burned some time near midnight on the night of August 21. At daylight on the morning of August 22, the remainder of the crew made its way to the river, where the men were cared for by Ranger Kaufman and his crew.

"The names of the men who lost their lives in this fire were George Strong, George Fease, E. Williams, and A. G. Bourette."

Pend Oreille National Forest

The Pend Oreille escaped better than most of the Idaho Forests, though there were several large fires. The big fires from the upper North Fork of the Coeur d'Alene cut the extreme southeast corner of the forest, south and east of the town of Clark Fork. Two fire fighters lost their lives in this fire. The following is quoted from the official report on the fire:

DeFaut Fire

"William T. Brashear, Forest Guard, in charge.

"The party in which loss of life occurred was working under the direct charge of W. E. LaMonte, who had previously been in charge of a trail crew on this forest and who had been pressed into service on the fire line under the exigencies then existing. This fire burned largely in the DeFaut Gulch, which is a small dry gulch near Cabinet, Idaho, and south of the Clark Fork River (now called Dry Creek). It was originally supposed that this fire came over the divide from the Coeur d'Alene National Forest, but later investigations showed that it came around the head of Elk Creek from the Cabinet National Forest and joined with the smaller fire already burning in the DeFaut Gulch. The fire already in existence in DeFaut Gulch had been brought under control by LaMonte and his men. The party, consisting of 10 men, were camped about one mile from the fire line in a clearing of two or three acres. At noon on August 19 the men came back a short way from the trenches for lunch. LaMonte had returned to camp to hurry up the lunch, which was late. He had hardly got into camp before he became aware of the fire which was sweeping in from the south, driven by a fierce wind. Brashear, the Forest Guard, had learned of the approaching fire and hurried back to camp from a trip over the fire lines. He met LaMonte coming out and at once started to warn the men. When he reached them the fire was coming with tremendous force. The men had already started down the road. When they reached the clearing it was plain to Brashear that the fire would overtake them. There was a spring in about the middle of the clearing and Brashear ordered the men to wet their clothes and bedding thoroughly, put their bedding over their heads, lie down near the spring, and wait until the fire had passed. They had hardly done this when the fire swept on them. At this juncture two of them apparently lost their reason completely, jumped up, threw off their bedding, rushed into the fire, and burned to death only a few yards from where the rest of the men lay.

"The fire had hardly passed over when a relief party was organized by Deputy Forest Supervisor E. G. Stahl and a search started for Brashear and his men. They were found on August 20 in the clearing in an unconscious condition, but were soon restored to consciousness. If the two men who perished had followed orders and stayed with the crew, they, too, would have been saved. As it was, some of the balance of the crew had their eyes and hands badly burned trying to restrain the two men who were killed.

"The men at the time the fire occurred were working under instructions to patrol the fire lines around the fire on DeFaut Gulch, which was then under control.

"The names of the two men who lost their lives in the fire were J. Plant and J. Harris."

Kaniksu National Forest

While there were fires all summer long on the Kaniksu, the area burned in 1910 was not excessive, and has been exceeded in subsequent years. The worst fires were outside the forest to the west.

The most destructive fire came over the mountain from the direction of Deer Park, and crossed the Pend Oreille River below Newport. Since this country was fairly well settled at the time, many homesteaders lost all they owned, and some of them barely escaped with their lives. Three homesteaders were caught by the flames and burned to death. These were Mrs. Ernest Dinehart, George R. Campbell and William Ziegler. One group of settlers escaped by getting in a boat on Marshall Lake. The Dalkena Lumber Company mill at Dalkena was burned.

Clearwater Forest

The Clearwater Forest at that time included the present Clearwater and most of the Lochsa and Selway River drainages, with headquarters at Kooskia under Major F. A. Fenn. It was mostly virgin wilderness country, with few trails. Lightning fires were spotted all over the Forest, and the widely scattered rangers were doing the best they could with small crews of five to twenty men to a fire. Many fires were never reached at all. When the big blow came August 20 and 21, the whole head of the Clearwater burned, from Weistas Creek up through Kelly Creek and across the Bitterroot Range 10 to 15 miles down on the Montana side. On the Selway River, the fire ranged through Moose Creek and much of the Upper Selway River.

| omitted from the online edition |

| Beaver Creek on the Clearwater Forest. (A. B. Curtis Collection, Courtesy University of Idaho Lbrary and Department of Special Collections and Archives) |

Moose Creek Crew

Since the upper Selway River is more accessible from the Montana side than from Idaho, the District Office in Missoula arranged for a firefighting crew to go in by the Lost Horse Trail from the Bitterroot to handle some of the fires on Moose Creek. Deputy Supervisor Ed Thenon took in one such crew. After a long journey they made camp on Moose Creek in a big cedar flat, eight miles above the Three Forks Ranger Station. At four o'clock it became pitch dark, but strangely enough Thenon did not seem to realize the cause of such untimely darkness. Thenon has written his own story, and it is such a vivid description of the experience of one crew in weathering the big fire that it is quoted.

"There were 30 men at this camp. Soon after supper the men began to retire, all but myself. Being one of those persons who use the bed extensively as a place where lots of time can be spent in thinking over one's troubles, I bedded down at 10 o'clock but did not go to sleep. A short time there after I heard something dropping on the tent and believing it to be rain drops I jumped up and went outside to see. I turned up my face but not feeling anything I spread out my hands but still could feel no rain. I re-entered the tent and lay down again and soon heard what I thought was a shower of rain. On going outside the tent again I discovered that there was a strong wind blowing through the tree tops and needles and refuse from the tree tops were dropping on the tent. I said: "Damn, why couldn't it just as well be rain," and went in and lay down again.

"Not long after this I heard someone outside my tent calling, 'Ed.' I recognized the voice as Louie Fitting's. I said: 'Hello, what's the matter?' He said: 'Come out here, I just saw a star fall on the hillside across the creek and it has started a fire.' I was outside at once and sure enough he pointed out a small fire starting well up on the hill across the creek from our camp. I knew it was out of reason to think a star could have set this fire, and in looking around to the west, the direction the gale of the wind was coming from, I saw the sky aglow with pink color spread across a width of several miles. I knew at once all about Fitting's star and where it came from.

"The fire was coming at a high rate of speed. Already it was beginning to throw shadows in our camp and we were right in the middle of its path.

"I aroused the men at once and ran out a few steps to the creek to see what the chances were for us there. I found the creek to be six or eight inches deep and about eight feet across with a strip of sand six feet wide which had been strewn along its edge by a sharp turn in the creek. A drift pile eight feet high and twelve feet long was at the upper point of this strip of sand.

"I ran back to the men who were all up by this time and upon seeing what was about to happen, some of them were beginning to cry and take on pretty bad, while others were as cool and calm as if this was an everyday occurrence, and these were the men who were to be so valuable to me that night and who followed out my every order throughout the night.

"I ordered the men to move everything out on the strip of sand and pile it up in one pile. Some of them were so excited they could do nothing and wanted to try to make their getaway ahead of the fire. I knew this was an impossible thing to do. I got up on a log and called all the men's attention to me long enough to advise them not to leave this spot, to stay together, and not to make an effort to save themselves by leaving the creek, that this could not be done. I said: 'If we all lie down in the creek during the crisis, no one will be hurt and we will pull through all right.'

"The cooler heads got busy moving our outfit to the sand strip while I was sizing up that drift pile trying to determine whether to set it on fire and try to burn it up before the crown fire reached us or leave it and try to keep it from burning until the overhead fire had passed over us. I did not want this drift and the crown fire over our heads to burn at the same time as it would make our position much worse. I got a water bucket and decided to keep the drift from burning until the overhead fire had passed on. The men were busy piling up our camp outfit not far from the drift pile. The fire was close by and the drift had already caught fire several times and had been put out with buckets of water. At this time someone reported that all the camp had been moved and I ordered them to wet all the canvas and throw it over the grub pile. By this time pieces of burning bark and cinders were coming down all about us. I was very busy with my drift pile. It was catching fire in places faster than I could put it out. I stopped long enough to tell the men to take all the blankets and soak them in the creek.

"Charley and Fitting had the two horses covered, heads as well as their bodies, with wet blankets. By this time the heat from the crown fire was plainly felt as it was only a few rods away and the wet canvas thrown over the grub pile had already caught fire.

"I was throwing a bucket of water on the grub pile when I heard a commotion among the men and left my work to see what it was about. We had rolled in the creek several times before this to keep our clothes soaked. I found that two of the men had completely lost their minds. One of them had become violently insane and three men were trying to hold him and to lay him down in the creek. The other one was dancing around and singing a lullaby.

"Right here was the time when those cool-headed men were of inestimable value to me as several other men became frantic at this time and wanted to rush off to, I don't know where. I ordered every man to get into the creek, lie down and put a wet blanket over his head. I set the lullaby boy down in the deepest water and told him to stay there and threw a wet blanket over his head. He would not lie down. The three men with the other fellow (he was our cook) had gotten him to lie down in the creek which had quieted him some. The others who became wild were also taken care of by the cooler-headed men and were lying down in the creek by this time. There were two or more blankets for each man so we were not short on these.

"I looked down the strip of sand and saw that all men except Charley and Fitting were in the creek. These two were dashing water on the blankets covering the horses.

"I turned to the grub and drift piles and found them both blazing. I grabbed up my bucket and dashed a bucket of water on the canvas and at this very moment the crown fire was directly over me and some sudden shift in the wind brought the heat right down upon me. The heat was so intense that it took my breath away. I swayed around a step or two with the empty bucket still in my hand and dropped to my knees. This was the critical moment, the crisis, and the only moment during this ordeal that I felt sure my time had come and that it was the end. On falling to my knees and for no particular reason I stuck my head into the bucket. This proved a blessing as I was able to draw a breath instantly and was relieved of the terrible strain. I got to my feet and with two or three steps I was in the creek where I lay down with the bucket still over my head. Having no blanket with me, I kept the bucket over my head for it had certainly saved my life.

"In perhaps five minutes the wind changed and this relieved us somewhat of the intense heat. The lullaby boy (I did not know his name) was still singing and now and then calling for someone to throw another bucket of water on him. I raised my bucket enough to look around some but saw no one moving except Charley who was throwing a bucket of water on the horses' blankets, then lying down again in the creek. Later he said that the blankets had dried out to such an extent in those few minutes as to catch fire from the cinders falling about us. The cook had quieted down considerably.

"The overhead fire had passed on and the heat was gradually moderating. Now we had the ground fire only to contend with, and soon we began getting out of the water to huddle around the heap of coals left by the burned drift pile to dry out our clothing. The snags and blazing old dead trees across the creek gave us plenty of light to see. The grub pile and canvas were a heap of ashes. Three men and I were suffering great pain in our eyes. They were smarting and burning so badly that it was almost impossible for us to open them enough to find our way around.

"To make sure that everyone was there and safe I had the roll called and found two missing. We could not come to any conclusion but that they had tried to outrace the fire and lost their lives in the attempt. Some of the men who knew their names began calling out to them. Soon we heard an answer from down the creek and the two deserters came wading up the creek to us. I scolded them some for leaving camp, and asked them why they did it. One of them remarked that they could not see how anyone could survive in this place so they went down the creek to see if they could find a place they thought might be safer. They found a large old cedar tree across the creek with the stump part high enough from the water to enable them to crawl under and they stayed there. After the fire had passed on they were much surprised to hear someone calling as they thought they were the only ones who had come through the critical time alive.

"Now there was considerable danger from falling timber. There were several standing dead trees near us that were burning and one had already fallen almost into our camp as a warning. A little later John wanted to use a bucket and walked down the sand strip to where one was, and just as he bent over and reached for it, a tree struck it and smashed it flat. If the bucket had been a foot further away the tree would have killed John instantly.

"The horses remained very quiet during all this excitement. This may seem very strange, and it is, but the fact that they had wet blankets over their heads and could see nothing that was going on around them accounted for it.

"The cook's condition had improved so much that he had no further need of attention from us. However, he did not get back to a normal state while here, but I was informed some weeks later that he had entirely recovered. The 'lullaby boy' was taken to an asylum.

"By this time it was getting daylight. Breakfast, and how to get it was now our problem. We sized up the ash heap under which were our supplies. One of the men got a chip and commenced to carefully scrape the ashes off the pile. The four of us whose eyes were affected were sitting down trying to nurse our eyes that were paining us so much. I had been snow-blind some years before and the pain in both cases seemed to me to be identical. One of the men said he knew of a remedy that would relieve our pain. He went over to the grub pile and commenced digging around and soon came back with half a cup of table salt and told us to dash some into our eyes. We did this and I thought it was more ashes than salt for a while, but it surely helped us and by using it often several times, our eyes improved nicely.

"The men now had the ashes pretty well scraped off the grub pile. One had a pot and was filling it with half baked beans. One had a pan and was carefully dipping up flour, while another pulled out a slab of bacon, fried on one side only, and breakfast was soon on the way. One was still digging around in the heap for coffee and sugar but found none. All sacks and wrappers were burned off the stuff, making a sweet mess of it. One took a large coffee pot and filled it from the creek and put it on the fire with the remark that it would look like we were having coffee anyway. 'Yes,' another one said: 'it ought to be good and stout too, from the ashes in that water.' We had some kind of a breakfast."

While this was going on, Ray Fitting, now Supervisor of the St. Joe Forest, was scouting the fire situation in the North Fork of Moose Creek, alone. He was caught in the sweep of the fire and took refuge in the creek under an overhanging ledge. The fire swept over him, burning the timber to the water's edge, but by keeping under water with his coat over his head he managed to survive the terrifying experience. He said he was really scared when the dead fish began to drift down past him. If the water was hot enough to kill the fish, he had visions of being boiled alive.

Kootenai Forest

The Kootenai suffered its heaviest loss on August 21, when the great fire from the Coeur d'Alene swept clear across the Clark Fork Valley, and over the divide, burning a very large area in the head of the Fisher River.

Another very large fire started on the Yaak River in the vicinity of Sylvanite and on the 20th and 21st swept far to the east in Pipe Creek and Big Creek. This fire did serious damage to mining developments near Sylvanite.

Nezperce Forest

The Nezperce had several large fires through the season, though losses were not as heavy as farther north. On August 20 and 21st, the town of Elk City had a narrow escape, the whole surrounding country being swept by fire. Forest Ranger G. I. Porter is credited with organizing the defense and saving the town.

Damages...

The reports available on the damage to forest and property are conflicting, incomplete and inaccurate.

The summary report for the National Forests of Region One shows the following:

Number of fires — 1,736, of which 223 were lightning

Area burned — 2,595,635 acres

National Forest timber destroyed — 5,408,641 M; value — $13,470,906

Total cost of firefighting to Government — $795,281

Outside the National Forests the figures are probably very incomplete and inaccurate, but show:

Area burned — 512,184 acres

Timber destroyed — 2,241,119 M

It is probable that the area burned in Montana and Northern Idaho was over three million acres and that seven to eight billion feet of merchantable timber was destroyed. Reports on damage to property are very incomplete. About one-third the city of Wallace was burned. Taft, DeBorgia, Haugan and Tuscor, all small towns, were entirely burned. The Forest Service probably lost six or seven strings of pack stock; and a large number of horses, cattle, pigs and chickens belonging to homesteaders and lumber companies were burned. The Forest Service lost at least four ranger stations. Damage to mine buildings and tunnels, particularly in the Coeur d'Alene Region, was great. The toll of human lives had probably been accurately determined as follows:

| Firefighters: | ||

| Coeur d'Alene (including St. Joe | - | 72 |

| Cabinet | - | 4 |

| Pend Oreille | - | 2 |

| Civilians: | ||

| Wallace | - | 2 |

| Taft | - | 1 |

| Prospector at head of St. Joe River | - | 1 |

| Homesteaders below Newport | - | 3 |

| 85 | ||

The greatest loss of valuable timber was on the St. Joe, particularly on Big Creek, Slate Creek and the Little North Fork. At the time of the fire the Milwaukee Lumber Company was constructing a railroad up Big Creek to log 100 million feet of white pine just purchased from the National Forest at $4 per M, besides a number of private claims. All of this was burned — one of the finest bodies of white pine in Idaho — but was partly salvaged.

On the upper St. Regis River, 99 million feet had just been advertised and bid in at $4.50 per M, but the contract not executed. Most of this was burned, but later partly salvaged.

The Coeur d'Alene lost much fine timber on the Upper North Fork. The damage on the upper Clearwater never was accurately known, but many million feet of fine, but inaccessible white pine were burned.

Salvage of Timber...

Before the ashes of the great fire were cool the Forest Service started action toward securing information for the salvage of as much timber as possible. It was recognized immediately that a very high percentage of the timber was so inaccessible that salvage was hopeless, but there were many bodies of good timber, particularly white pine, which offered possibilities.

Timber survey crews and appraisers were organized as rapidly as possible, particularly through 1911, and available chances were cruised, appraised and advertised as fast as they could be reached. The existing lumber companies in Idaho and Western Montana were anxious to do their part, and many of them transferred their operations entirely to fire-killed timber.

The major salvage operations were as follows:

Coeur d'Alene

The Rose Lake Lumber Company logged a large amount of white pine on the Upper North Fork from McPherson's up into Independence and Trail Creeks. The timber was driven down river. The Stack-Gibbs Lumber Company operated on lower Big Creek and adjacent river areas. There were also many smaller sales made along the North Fork.

St. Joe

The Milwaukee Lumber Company had started a railroad into Big Creek before the fire. This railroad was extended and that company logged Big Creek until 1915. That company also logged timber in the Little North Fork, including Loop Creek; McGoldrick logged Slate Creek, and Bogle and Callahan the upper Little North Fork.

Lolo (St. Regis Drainage, now on Cabinet)

The Polleys Lumber Company logged Rainy Creek and the St. Regis River up as far as Denniemore Creek. They also logged Packer Creek and Brimstone. The Mann Lumber Company took out all the timber from the West and Middle Forks of Big Creek, including considerable green timber. Westfall had a mill setting at Borax and took several million from the upper part of the St. Regis River, largely spruce, which was very severely burned.

Cabinet

A number of units near Noxon were logged after the fire, including Pilgrim Creek and Bull River. These were mostly small or medium sales.

There is no clear record of the total amount of fire-killed timber salvaged. Most of what was salvaged was taken out in 1911 to 1914. The total regional cut for these four years was 539 million. Possibly two-thirds of this was fire-killed or fire-damaged timber, which would make the salvage about 300 million out of a total estimated loss of National Forest timber of 5 to 6 billion feet, considerably less than 10 percent.

Most of the operators in fire-killed timber made very little profit. Some of them lost money. For one thing, the Forest Service was somewhat too reluctant to let them skim the cream and take the best timber first. Some good timber was lost while they were cutting less good timber. It is evident that from this experience in salvaging fire-damaged timber there should be little restriction in getting the best first.

The burned timber commenced to check and blue almost immediately. The spruce went first, and by 1912 it was very badly checked. White pine was logged up to 1914, and a little in 1915, though only the largest trees were then merchantable. Fir and larch lasted the longest and some of it was logged for mine timber up to 1918. Very few cedar poles were salvaged, but post timber is still being cut from 1910 burns.

After-effects of the Fire

The burning of three million acres of timber and young growth, including some of the most valuable white pine stands, was a staggering blow to the National Forests of the Region. The direct loss of that much timber and young growth was not the only loss. It is true that fire breeds fire, and the 1910 fire started a vicious circle which has greatly increased the difficulty of protection since 1910. The burned areas, with heavy snags and dead timber have proved the breeding places of innumerable fires which have burned additional areas and so created new hazards. It is not at all impossible that the burned area since 1910 has been twice as great as would have happened if the 1910 fire had not occurred.