|

History of Smokejumping

|

|

1940

First Practical Use of Smokejumpers

As a result of the experiments of the previous year, Regions 1 and 6 each organized a small squad of smokejumpers for the 1940 fire season. The latter Region developed its squad around a nucleus of Chelan Forest guards who had jumped during the experiments of the previous fall, while Region 1 selected a project leader and sent him to Winthrop to undergo initial spring training with Region 6. The technician who had been provided by the Eagle Company for the experiment of the previous fall was retained to serve both Regions through the training season.

Due to a light fire season within the Region 6 sphere of activity, their squad had little action during the summer. On the other hand, Region 1 jumpers handled nine "selected" fires in a season of the highest lightning fire occurrence on record. An analysis of the nine fires indicated a net overall saving of approximately $30,000, or nearly three times the cost of the entire project.

The first actual fire jumps were made on July 12 by Rufus Robinson of Kooskia, Idaho, and Earl Cooley of Hamilton, Montana, on Martin Creek in the Nezperce National Forest. Of historic note also is the first successful "rescue jump" made by Smokejumper Chester N Derry 3 days later, to an airplane crash in the Bitterroot Forest. This last incident, together with the subsequent parachute training of Dr. Leo P. Martin of Missoula as the first "jumping doctor," marks the initial milestone in rescue jumping — an activity that continues to develop and expand along with smokejumping. Both Derry and Dr. Martin were later killed in airplane crashes.

An interesting sidelight — and one with far-reaching effects — pertains to the visit of four U.S. Army staff officers to the parachute training camp at Missoula in June. One of these, Major William Cary Lee, later employed Forest Service techniques and ideas in organizing the first paratroop training at Fort Benning, Georgia.*

*Major Lee subsequently commanded the 101st Airborne Division which he took to England and trained for the Normandy invasion. He became first Chief of the Airborne Command and is regarded as the unquestioned father of U.S. airborne doctrine.

1941

Smokejumpers Used as "Shock Troops" on Bigger Fires

By early spring of 1941, it had been decided that the smokejumper project would be transferred wholly to Region 1 and centered at Missoula for the coming season. Success of the previous year's activity only partially accounted for this decision. Region 1 contains about 8 million acres of roadless area, of which the Regional Headquarters at Missoula is the geographic center and logical hub. Furthermore, the Johnson Flying Service at Missoula could provide the planes, pilots, and mechanical service which were extremely difficult, if not impossible, to obtain elsewhere at that time. In taking over the project Region 1 also provided jumpers on call for Regions 4 and 6, to the limits of availability.

Increased funds allowed an expansion to a three-squad outfit totaling 26 men, including nearly all of the jumpers who had served in the previous year's squads.

An outstanding accomplishment of the year was the development of a static line, which was adapted to the Eagle backpack and used throughout the season. The use of this device, which eliminates the manually controlled ripcord, appeared to have a remarkable effect on the trainees in reducing the intensity of nervous reactions that generally precede the first few jumps. This, together with a more systematic and intensive course of ground training and careful selection of candidates, resulted in a highly successful session, with all trainees easily qualifying.

Intermittent showers well scattered throughout most of Regions 1 and 4 resulted in an extremely mild fire season, and had it not been for a rather serious outbreak in the North Pacific Region in late July, the value of the smokejumping unit would not have been so apparent as during the previous year. As it turned out, the jumpers again handled or reinforced nine fires, this time with an estimated saving in excess of $30,000. Also for the first time, an organized force was jumped to a threatening fire that had escaped from the initial attackers and had reached an area of 15 acres in extremely bad fuels. While the jumpers alone did not control this fire, they were able to hold it in check through the heat of a bad "burning day" until the arrival of adequate ground forces.

Through the season there were increasing demands for material on the smokejumpers from feature writers and other interested sources of news dissemination. A representative of Scientific Films took color pictures of the smokejumpers in training for a special newsreel. Paramount Pictures, Inc., entered into a contract with the Forest Service for the aerial and parachuting sequences of a forthcoming film to be adapted from a magazine story by Thelma Strabel. This filming was completed during the month of September.

1942

First Effects of the War on Smokejumping

Continuing in 1942 as a Region 1 project, a further expansion led to a four-squad unit, and only the impact of war prevented greater development. As it was, age limits and experience requirements had to be liberalized in order to secure recruits, though physical standards were not lowered.

The training season opened with only five experienced jumpers on hand. A considerable number had entered military service, while others were occupied as instructors with the C.A.A., or at Army and Navy parachute rigger schools, and in essential war industry. Of the 33 recruits that started training, only a few were experienced smokechasers and, to offset this deficiency, a greatly intensified program of fire control training was carried out.

The equipment situation was almost as critical as that regarding manpower, but a few chutes not acceptable to the armed services were picked up at intervals and converted. This necessitated experimentation, out of which came the outstanding development of the season, the Derry slotted chute which is maneuverable, provides easy opening, a slow rate of descent, and relatively little oscillation. This made it possible to convert any standard flat-type chute by adding the slots and guidelines.

Considerable moisture during June and July held the fire season back, and even in August, comparatively few fires occurred which warranted the use of jumpers, although some valuable use was made of them on a few occasions. A local concentration of lightning fires in the remote area of the Bitterroot and Nezperce Forests in early September, however, more than paid for the entire season's cost of the project. By this time, a few more jumpers had left to join the armed forces, but all of those remaining were concentrated in the critical area, and for about a week men were jumped to fires as rapidly as chutes could be retrieved and repacked for service. The total score for 1942 credited to smokejumpers was 31 fires controlled alone and 4 more controlled with the aid of ground forces. The indicated savings in suppression costs were approximately $66,000.

|

| Parachute packing shed at Moose Creek Air Field, Bitterroot National Forest. 1940/43 |

|

| The Derry slotted chute became standard smokejumper equipment in 1942 because of its better maneuverability, slower descent rate, less oscillation, and less opening shock than the flat-type chute. |

1943

The Civilian Public Service Program — First Training of Military Personnel

By the spring of 1943, the manpower shortage had reached a critical stage and, despite the training program of the previous year, again only five experienced jumpers, including the instructor, were available. The most strenuous efforts at recruiting had resulted in the selection of four young men whose youth or minor physical defects had up to this time kept them out of the Army, but in the meantime, a number of inquiries had been received from individual 4-E (conscientious objector) draftees in public service camps who wished to secure noncombatant work involving exceptional physical risk. This paved the way for the parachute program of 1943, in which all C.P.S. camps were solicited for volunteers. By a careful sorting of 300 applications, 62 candidates were selected, a majority of whom were from the so-called "peace churches" (Mennonites, Brethren, and Friends). Meanwhile, Regions 4 and 6 had entered the program, each sending fire control men to Missoula to be trained as squad leaders and riggers to overhead the C.P.S. squads that would be assigned to them later. About 70 new men were trained during the 1943 session and again there were no failures, although a few received injuries in training which prevented them from jumping on fires during the summer.

Training facilities were enlarged by the addition of an obstacle course, a plane mockup and a number of lesser improvements in both equipment and techniques. The War Department released a quantity of canopy material which amply provided for the season's needs, and shortages in other materials were overcome by improvisations and substitutions.

The fire season of 1943 proved the exception to the rule backed by 30 years of recorded history — that three consecutive "easy" seasons do not occur in the Northern Region. However, the usual fall break did not materialize and the Region experienced a severe drought in September and early October. Since most of the ground forces were composed of 16- and 17-year-old boys who returned to school or entered military service by early September, the smokejumpers were practically the sole remaining group to carry this post season fire load. As in the previous fall, a flurry of activity again resulted in large savings in suppression costs, the season's estimate for Region 1 being $75,000 for a total of 47 fires.

|

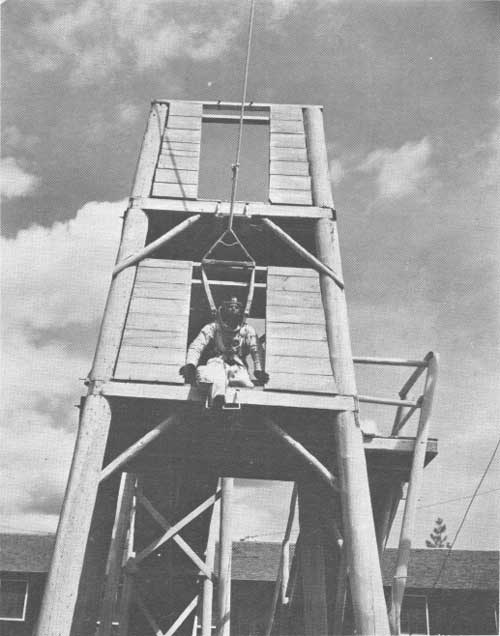

| Jump training tower at Ninemile smokejumper headquarters, 1943-1953. |

An unusual feature of the season's activities was the parachute training of rescue units from the military services, involving about 25 individuals of the U.S. Coast Guard, Canadian Air Observer Schools, and U.S. Army Air Forces. This "rescue training" began shortly after the close of the regular session and extended with few breaks until December 10. About half of those trained were flight surgeons of the Second Army Air Force and the Second and Third Arctic Rescue Squadrons.

Closely connected with this activity was the establishment of a Second Air Force Search and Rescue Section, with the Forest Service an active participant. This was initiated by Captain Frank Wiley of the U.S. Air Force.

1944

Smokejumping No Longer an Experiment—Makes Actual as well as Theoretical Savings

Anticipating a continuing shortage of smokejumper candidates, arrangements were made with Selective Service and the National Service Board for religious objectors to keep as many of the trained C.P.S. men as wished to remain through the winter and again be available as jumpers in 1944. This resulted in the retention of about 60 percent of the entire group, those retained being placed on a variety of winter projects within the three Regions. The C.P.S. program was expanded in the spring to a total of 110 men and, despite a proportionately smaller number of volunteers from which to make selections, the results were again very satisfactory. Distribution of the units was essentially the same as in 1943, with increases in the number of jumpers assigned to the three Regions.

Training of the new men was conducted in Region 1, as was most of the refresher training for the older men, and training techniques were further improved. An important new feature was the use of a public address system (field amplifier) by means of which the instructor on the ground could guide and direct the trainee through his first few jumps.

A further centralization of smokejumper use in Region 1 led to a slightly different arrangement of forces at the various bases. It was found that most effective use of jumpers could be raised or lowered in size according to probability of use and was kept filled from the nearby "feeder base" where 40 to 50 jumpers were kept continuously on project work.

The fire season of 1944 was hardly up to normal in most of the area covered by the jumpers, but the occurrence of lightning fires was high and there were a few bad "spots" as well as periods of concentration. Smokejumper activity was greater than ever before and well distributed over all three Regions. Considerably more than a 100 fires were handled by jumpers — about 75 percent from the Missoula base. Jumpers were used on larger fires than previously and in larger groups, and the instances of substantial savings were correspondingly greater.

There was no further training of military personnel, but the expansion of rescue units and their success led to greater demands for technical information and special equipment, making it necessary to keep a larger force of riggers employed during the winter season.

Perhaps the most significant change in Region 1 was the inclusion of parachute jumpers in the regular organization. Hitherto, the smokejumper unit had been organized as a special force — an adjunct to the ground firefighting groups, financed from special experimental funds. In 1944, for the first time, a number of National Forests reduced their ground forces, thus becoming wholly dependent upon the smokejumpers in certain large areas. The results seemed to justify the action, which was a move toward greater economy as well as increased efficiency.

Another important feature of the 1944 season was the first use of large military airplanes for smokejumping. Region 6, through cooperation with the U.S. Marine Corps, successfully employed Navy DC-3's for actual fire jumps in Washington and Oregon. In Region 1, Ford tri-motors and Curtis Travelairs continued in use as the workhorses of the parachute project.

1945

The "Continental Unit" — First All-Out Air Control Project

As the last of the "war years," 1945 will have an important place in the history of smokejumping. Continued expansion of the C.P.S. program, plus the return of a few war veterans, increased the total number of smokejumpers to 220, of which nearly 100 were men with one or more previous seasons' experience. All of the training of new men and most of the refresher training was handled at the Ninemile base near Missoula, and the final distribution resulted in a substantial increase in the number of smokejumpers over the previous year in all three Regions. Principal bases were maintained at Missoula, Montana; McCall, Idaho; Twisp, Washington; and Cave Junction, Oregon.

The fire season of 1945 was far more severe than at any time since 1940. In Region 1, burning conditions became acute at times in some of the areas dependent upon smokejumper action, and there was practically no letup in activity from July 11 through the first week in September. The record for 1945 shows that in the three Regions, smokejumpers were used on 269 fires, with a total of 1,236 individual jumps. From the four operating bases, the jumpers covered fires in 23 National Forests located in the States of Montana, Idaho, Washington, Oregon, and California. They also jumped to fires in Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks, U.S. Indian lands, private timber association lands, and in one instance, just over the International Boundary in Canada.

A far from complete cost analysis, covering only two of the three Regions, indicates a net saving of $346,780 for the season; but in numerous cases it was apparent that the savings on a single fire might conceivably have equaled the entire figure. To a far greater degree than in any previous year, smokejumpers were used in large groups to spearhead control action on the larger and more threatening fires — often with complete success.

Among the many events and occurrences of the year, the following are of greatest importance:

1. Death of Pilot Dick Johnson in an airplane crash near Jackson, Wyoming, March 2. Dick was one of the ablest of mountain pilots and one of the first to fly the smokejumpers.

2. First experimental "air control area" set up in Region 1. Two million acres of roadless wilderness, including parts of the Flathead, Lewis & Clark, Lolo, and Helena Forests, handled by air detection and smokejumpers to the exclusion of most of the ground forces. This became known as the "Continental Unit" because of its location adjacent to and on both sides of the Continental Divide.

3. The training and equipping of 14 officers and enlisted men from various Alaskan and Canadian stations of the Air Transport Command as parachutists. This was conducted at Missoula in March and June. The purpose was to provide additional personnel to jump with para-doctors on search and rescue missions.

4. First active participation of smokejumper and Army paradoctors together in rescue missions. Two instances involving severely-injured smokejumpers were successful. A third concerned a hunting accident in which the victim was brought out alive but died within a week, and the fourth instance involved two Army fliers, both of whom were found to have been killed in the crash. In two other cases, smoke jumpers parachuted unaccompanied by a paradoctor to aid and pack out injured men. The total number of recorded rescue jumps for the year in Region 1 is 55.

5. Training of the 555th Battalion of Negro paratroops in timber jumping and firefighting to combat Japanese balloon fires. This was conducted at Pendleton, Oregon, by parachute instructors from Missoula. Since the balloon menace did not materialize, the 300 paratroopers were used as auxiliary suppression crews on large fires in Regions 1, 4, 5, and 6.

6. Procurement of two UC-64 Noorduyn-Norseman airplanes by loan from the Army and their use for transporting smokejumpers in Region 6.

In summarizing the activities of 1945, it may be said that, while smokejumping has been regarded as successful for a number of years, this was the first season in which its importance was fully demonstrated. Region 1 had a force of 144 well-trained smokejumpers and the fire season was severe enough to give them a thorough test. It also became evident that smokejumping has two major purposes: (1) As an economical substitute for the costly installations and difficult training and supervision problems of a widespread "back-country" smokechaser organization. (2) As a quick and effective means of placing skilled, hard-hitting crews on those fires that have escaped or threaten to escape the initial attackers.

|

| THE LAST MODEL of the Ford tri-motor planes used by the Northern Region for delivering smokejumpers and aerial cargo to forest fires. Built in 1929-30, this Ford Model 5-A-T carried eight smokejumpers and their equipment. This model was used out of the Missoula Aerial Fire Depot up until 1967. |

1946

Reconversion — End of the C.P.S. Program and First Wholesale Recruiting of Ex-GI's

With the end of the war, the C.P.S. program was rapidly liquidated and the three Regions engaged in smokejumping faced the necessity of developing a new organization around the small group of trained overhead that remained. In spite of this fact, however, there was no reduction in the size of the project, and a training program much larger than heretofore was organized and put into action.

While the overall number of jumpers remained about the same as in the previous year, there was a further expansion in operational area. The National Park Service provided funds for a small group out of the Missoula contingent of jumpers to be available on call for fires in Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks and the California Region (Region 5) similarly financed a portion of the Cave Junction (Oregon) outfit. The latter group was for use on fires in the Siskiyou Mountains of northern California.

Of the Region 1 group of 164 jumpers, 84 percent were ex-servicemen and about 40 percent of the total were college students, of whom a little more than one-half were students of forestry. Numerous minor developments in both training techniques and equipment kept pace with the expanded training program, and the addition of a C-47 to the contractor's fleet of airplanes made it possible to transport larger crews at greater speed on several of the most threatening fires.

The fire season was not as critical as in the previous year, but the occurrence was considerably greater, and more fires were actually jumped to than in 1945. A cost analysis submitted by Region 1 shows a saving of $376,560 through the use of smokejumpers on 202 fires.

A tragedy of the 1946 season was the death of Pilot Bill Yaggy in an airplane crash near Dixie, Idaho, in February. Bill was a smokejumper himself in 1941; afterward he became a pilot and flew jumpers on many training and firefighting missions.

|

| First used in 1946, C-47 planes are still used for smokejumping, to transport both cargo and nonjumping firefighting crews. |

1947

Expansion — Smokejumping Extends to the Mexican Border and Into Canada

Highlights of the 1947 season are more important for their long-range significance than for the immediate results obtained.

There was little change in the size of the project, but with 55 percent of the 1946 organization available at the beginning of the season, the job of recruiting and training was not such a prodigious problem as it had been in the previous year. As would be expected, the 1947 squads were more effective and, despite the mildness of the season, there were numerous "critical" fires adequately handled.

There was a drop in the number of smokejumper fires over the previous year, the total being 131 for the Region 1 unit, and no cost analysis was made, as it was felt that previous estimates had served their purpose and that no question existed as to the economy of this method of firefighting. A total of 576 individual jumps were made to fires and an additional 37 jumps on rescue missions involving five separate cases, one of which was participated in by Dr. Amos Little.

Newsworthy facts of the 1947 record are as follows:

1. Regions 4 and 6 developed training centers and conducted their own parachute training. Previously this had been carried on at one large central camp near Missoula.

2. A foreman and eight jumpers from Region 1, and a Noorduyn-Norseman plane with pilot from Region 6, were detailed to the Gila National Forest in southern New Mexico for the period May 25 to June 25. This was in response to a request from Region 3 (Arizona and New Mexico) for an experimental trial at smokejumping during the spring season of lightning fires in the Gila Wilderness Area.

3. The Provincial Forest Service of Saskatchewan, Canada, developed a smokejumper project after representatives had conferred with the Regional Office at Missoula. Region 1 parachute technicians gave advice and the actual training of smokejumpers was accomplished by a commercial firm headed by a Canadian who had been trained as a rescue jumper at Missoula during the war.

4. Death of Dave Godwin, newly appointed National fire control chief, in an airlines crash in the Virginia Mountains on June 13. More than any other individual, Dave was responsible for the initiation of the "Parachute Project" and his continued interest and support contributed much to its success.

5. Smokejumpers from the Missoula base participated in combined aerial attacks on two fires that were bombed from the air as a part of the Forest Service — U.S. Army cooperative fire bombing project. Smokejumpers also participated as ground crews during the fire bombing experiments in the Missoula area.

6. Two groups of 10 men each from the Air Rescue Service which operates under the Air Transport Command, U.S. Air Force, were trained as jumpers at Missoula during the fall. These groups were composed of medical and training officers and enlisted men, and they were given the regular course of parachute instruction as modified to meet the requirements of rescue jumping.

1948

Smokejumping at Lowest Ebb — Northwest Experiences Floods Instead of Fires

Starting out with severe floods in Montana, Idaho, and Washington, moisture continued in abnormal quantities throughout the usual fire season. There was normal jumper activity for the squad assigned to New Mexico and some of the Missoula jumpers got workouts in southern Idaho later in the season but, in Region 1, 1948 was definitely a freak year. In order to hold the unit at full strength. Missoula jumpers were assigned to flood damage repair projects where they are credited with having accomplished a considerable amount of important work. It was also a good year for equipment development, slack periods of technicians being utilized in testing and perfecting new devices for increasing efficiency and safety.

Training of jumpers in the evacuation of injured persons by means of a newly designed wheel stretcher that could be dropped from an airplane was put to good use during the fall. A lost hunter, in serious condition from exposure, was transported 14 miles over rough terrain at an average rate of 4 miles an hour.

Word was received of the death, June 25, of retired Major General William Cary Lee, early friend and supporter of the smokejumper project (see 1940).

1949

Another Busy Season — First Major Tragedy in Smokejumper History

According to the record, 1949 was the second most active year since the inception of smokejumping, being exceeded only by 1945 in total number of jumps and by 1946 in number of fires on which first attack was initiated by jumpers.

The season was exceptionally dry — approaching the critical in the southwestern part of Region 1 and definitely critical in certain sections east of the Continental Divide and in Region 4.

News events of the season are overshadowed by the tragic occurrence of August 5 on the Helena Forest's Mann Gulch fire. Twelve smokejumpers and a District guard (himself a former jumper) were fatally burned in a blowup that occurred during the early evening of that fateful day. The jumpers had landed safely at 4 p.m. and were proceeding to attack the fire in the routine manner that would ordinarily have been effective. The sudden blowup trapped 16 of whom only 3 escaped. The tragedy was in no way connected with the jumping activity and would undoubtedly have occurred had a crew of ground-transported men been caught in a similar situation.

Experiments in picking up jumpers and jumper equipment by helicopter were conducted as a part of the helicopter experiment carried on at Moose Creek Ranger Station in the Bitterroot National Forest, but these tests were inconclusive and it was planned to continue them another year.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

smokejumping/sec2.htm Last Updated: 12-Sep-2011 |