|

A History of The United States Forest Service in Alaska

|

|

INTRODUCTION

There are three geographical approaches possible in the study of forest history. It may be studied as a part of a world movement, as Bernhard Eduard Fernow did in his classic Brief History of Forestry in Europe, the United States and Other Countries (1907); or from the standpoint of a single nation, as Jenks Cameron, John Ise, and Samuel Trask Dana studied the movement in the United States; or from the standpoint of a single region, as Filibert Roth studied the movement in Wisconsin, as Charles McKinley treated the Pacific Northwest, or as others have studied particular localities.

|

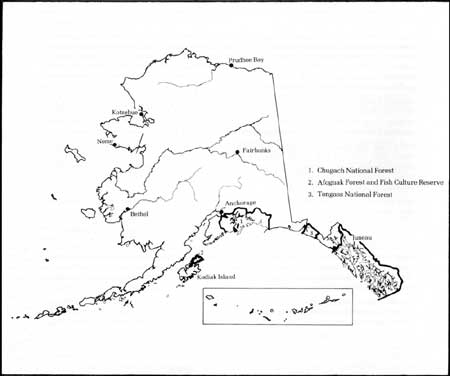

| I. The three major national forest areas in Alaska. (click on image for a PDF version) |

As a world movement, forest history offers an interesting and inspiring western story. Forest conservation principles were well established in western Europe by the beginning of the nineteenth century when the movement spread to the European colonies and to the newer nations of the world. In the United States, forestry practices of the Old World were introduced and adapted to different physiographic conditions and governmental structures. From the United States, in turn, forestry practices were exported to the Philippines, China, Canada, and Latin America. There was a great deal of interdependence in the movement, for science and scholarship do not recognize national boundaries. The comparative history of the movement offers both interesting and challenging opportunities for research.

Yet, though the movement was worldwide, its history varied from nation to nation. The structure of the various governments, differences in soil, topography, and economic structure, and political, historical, and cultural traditions all affected the movement. The earliest forestry movements in the Philippines and in China, for example, were started by American-trained foresters and modeled on the forest administration of the United States; but the forces and accidents of history created in the Philippines significant modifications of the American system—and in China a complete break. The study of forest history, from a national point of view, is a significant field of scholarship.

A third approach—the one used in this study—is regional. National policies of resource management have never operated uniformly in all parts of the United States. Our government is federal rather than unitary, its power divided between a central government in Washington and governments on the state and local levels. The transition from dual federalism to cooperative federalism has historically involved both federal and state court decisions, as well as state, local, and national politics. The effects of land legislation must be studied from a regional point of view; in fact, much federal land legislation has been designed for particular regions. Land resource problems frequently become important regional political issues, as did the Alaskan national forests in 1910, 1915, 1921, and in the 1970s.

The regional approach is useful from another standpoint. Administration in all federal bureaus and agencies having to do with resource management is decentralized, with a great deal of interplay in decision-making between national and regional offices. The national forests of Alaska were originally part of District 6, which also encompassed those in Oregon and Washington. In 1921 they became an autonomous administrative unit, District 8 (later, Region 8 and then Region 10). Just as the states have served as social laboratories for working out experiments in administration, so the administrative regions have served as technical and scientific laboratories for working out plans for resource management. The history of the Forest Service is not only that of the central or Washington Office but also that of the various regions.

In undertaking this regional study, the historian must bear two things in mind. First, the Alaska Region of the Forest Service does not exist in isolation. Its relationship to the national story of resource management and to other administrative regions must be recognized. A study referring only to the region is likely to be antiquarian in nature; one related to national developments will illuminate both regional and national history.

Second, subregions within the region must be recognized. In Alaska, the Chugach and the Tongass national forests represent both different physiographic provinces and divergent historical and economic developments. The differences here are paralleled in the Pacific Northwest by the distinct economic and social climates of opinion on the east and west sides of the Cascades.

|

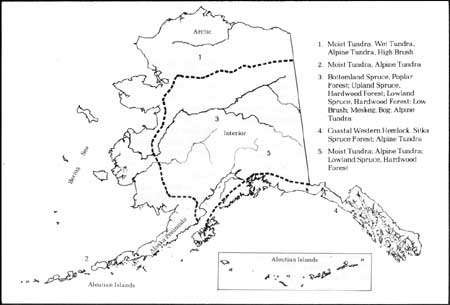

| II. Forest varieties of Alaska (click on image for a PDF version) |

The Alaska Region of the Forest Service is a significant area for study from several points of view. It was, with the exception of the Philippines, the most isolated area to come under American forest management; but where George Patrick Ahern was able to build on the Spanish forest regulations in the Philippines, William Alexander Langille started from scratch in Alaska. The early political and administrative history of the forestry movement has been marked by conflicts between conservationists and frontiersmen, and indeed it still is. These frontiersmen included the "frontier individualists," who resented regulation as an infringement on their freedom, and the "corporate frontiersmen," who desired to exploit resources for business reasons. Both frontier individualism and economic colonialism manifested themselves in the public land states of the West, but in no area did they come into such direct confrontation with federal foresters as in Alaska. In his "Rhyme of the Three Sealers," Rudyard Kipling wrote, "and there's never a law of God or man runs north of fifty-three." This phrase was often quoted by Alaskans to apply to the forests as well as to the sealing industry.

The setting and forest resources of Alaska were also wholly different from those in the other states and territories. The spruce-hemlock forests of the coast and the boreal forests of the interior found no counterpart in other areas. The early history of most other administrative regions in the West had much to do with range and grazing issues, but grazing was of minor concern in Alaska. Logging in the western regions was by animal and steam power; in Alaska, handlogging was the common practice. Fisheries and mining claims presented greater administrative problems in Alaska than in other areas. In the backcountry of the West, pack mules and saddle horses were the standard mode of transportation; in Alaska, boats and dog teams were essential. At the time that the first forest reserves were created, in the 1890s, all the public land areas in the West were either states or organized territories on the verge of statehood; in Alaska the long struggle for self-government, and the frustrations that accompanied it, had a strong effect on the programs of resource management.

Individual personalities and achievements play a major role in history. Regional leaders, such as Edward T. Allen in the Pacific Northwest, Charles Shinn in California, and Smith Riley in the Rocky Mountain West, greatly aided the national forestry movement. In Alaska a similar group of men played great and often heroic parts in the forestry movement. Here the roles of such Forest Service men as William A. Langille, William Weigle, Charles Flory, and B. Frank Heintzleman deserve major recognition.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

10/history/intro.htm

Last Updated: 06-Mar-2008