|

Timeless Heritage: A History of the Forest Service in the Southwest |

|

Chapter 13.

Recreation

Recreation in the national forests, in terms of numbers of people participating, diversity of activities, and accommodation by the Forest Service, is largely a post-World War II phenomenon. Although the Organic Act of 1897 advocated public use of the national forests, recreation was not generally perceived as a significant use of forest resources. Certainly in the Southwestern Region, foresters and the public were generally preoccupied with timber, grazing, and mining. Recreation became a factor in national forest use in the 1920's, when automobiles made the forests more accessible. Roads, recreation facilities, and opportunities expanded significantly in the 1930's, with assistance from the Civilian Conservation Corps and other New Deal agencies. Recreation became a major factor after World War II, often exceeding timber, grazing, or mining in economic impact upon the Southwest. It has become the major area of Forest Service involvement with the public.

Sunbelt residents and people from all over the Nation have become aware of and interested in the welfare of the southwestern forests. The forested lands are important, not only for the traditional uses of timber, grazing and mining, but as watersheds, wildlife habitat, and recreational areas. People use the forests for year-round experiences, for relief from the summer heat, and for physical and scenic alternatives to the urban lifestyle. Phoenix and Albuquerque are among the fastest-growing metropolitan areas of the United States, and the national forests have become their summer retreat and their winter playground. For example, 1.5 million people visit the Cibola National Forest, near Albuquerque, in an average year, and the Tonto National Forest, adjacent to Phoenix, receives 25 percent of the total visitors to national forests in the region. [1] Efforts to accommodate this unparalleled use have been difficult, but in good measure successful.

|

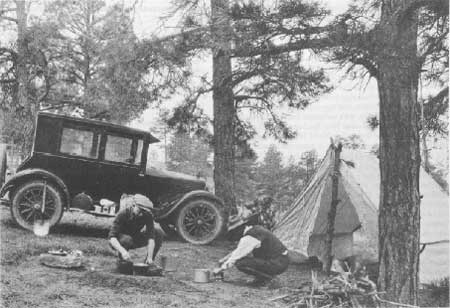

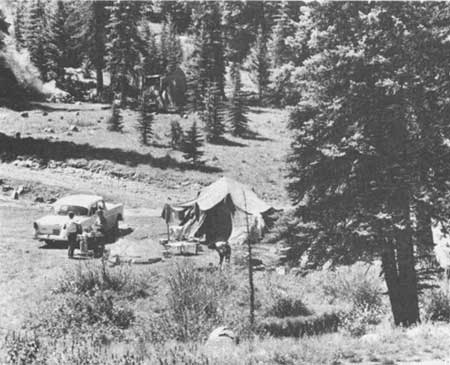

| Figure 35.—Camping out on the old Manzano (now Cibola) National Forest, early 1920's. |

Camping is available in highly developed campsites with all of the amenities of civilization, or in the raw and untrafficked wilderness. There are highly developed, modern resorts at Red River, Ruidoso, and Taos for downhill skiing and quiet and remote trails for cross-country skiing. There are great pine forests in the uplands and saguaro cactus in the Upper Sonoran Desert. Paved highways provide access to at least the periphery of every national forest in the region, and designated off-road vehicle ways and foot trails provide access to the interior areas. Major recreational activities in order of use in the Southwestern Region are recreational travel, camping, picnicking, hunting, fishing, hiking, viewing scenery, gathering forest products for pleasure, winter sports, swimming, interpretive services, cabins, boating, organization camping, horseback riding, hotel and resort use, nature study, and water sports. [2] Table 9 briefly reviews developed recreation sites in the region.

Table 9. Developed recreational sites in Region 3 (1983)*

| Site | No. | People at one time |

Visitor- days |

|---|---|---|---|

| Campgrounds | |||

| Family | 252 | 24,646 | 3,812.3 |

| Group | 20 | 1,985 | 166.1 |

| Picnic grounds | |||

| Family | 112 | 9,323 | 1,063.3 |

| Group | 8 | 665 | 20.9 |

| Hotels, lodges, & resorts | |||

| Forest Service | 2 | 250 | 72.2 |

| Private | 14 | 2,597 | 250.6 |

| Boating Sites | 40 | 6,924 | 656.3 |

| Swimming Sites | 4 | 800 | 158.8 |

| Winter sports | |||

| Snowplay areas | 6 | 1,565 | 33.2 |

| Ski areas | 9 | 17,475 | 548.3 |

| Recreation residences | 1,325 | 6,711 | 417.4 |

| Organization sites (private) | 39 | 8,295 | 576.4 |

| Interpretive sites | 88 | 3,749 | 184.9 |

| Developed cultural resources | 11 | 105 | 5.1 |

*The Southwestern Region had over 20,000 inventoried cultural resources in 1986.

Greater population pressures have also generated an increased need for the preservation of additional wilderness areas. Over 2.7 million acres have been set aside in the Southwestern Region for wilderness management. Indeed, it was in the Southwestern Region, under the direction of Aldo Leopold, that legally designated wilderness areas became a reality. The establishment of the 750,000-acre Gila Wilderness in 1924 gave birth to the National Wilderness Preservation System, which nationwide comprises 257 areas and 79 million acres of public lands. [3] A number of new wilderness areas, totaling 903,000 acres, were established on the national forests of the Southwestern Region in the 1980's. Before then, there were 1.8 million acres in the wilderness preservation system in the region. Management of the wilderness areas is provided for under the authority of the Wilderness Act of 1964. [4]

Before 1920 in the Southwest, the public and the Forest Service perception of forest recreation generally included hunting, fishing, hiking, camping, picnicking, and sightseeing. Forest recreation was regarded as primitive, individualistic, and very personal. The attitude is reflected in a 1937 recreation study, which explained:

We should contribute information in regard to everything that has to do with forest recreation, that is, with the close contact between people and the quiet, restful spots of the natural forest where they can digest the chaotic items of their lives and see themselves in the correct relation to both civilization and nature. [5]

Interestingly, this perception of recreation is very similar to views held today by Sierra Club and Wilderness Society members. As Sigurd F. Olson, then president of the Wilderness Society, wrote in 1970:

Wilderness does things to people. I have watched its magic all my life, how it penetrates sophistication with its silence and beauty, sweeping away the myth of unlimited material progress. Under the impact of wilderness people change, become more intuitive, alive, and aware. They sense man's long past; they become more tolerant, humble, more humane. [6]

The contemporary emphasis by the Forest Service in many areas on dispersed recreation, as opposed to developed recreation, stresses restful solitude, freedom from noise, natural scenery, and uncrowded forests and wilderness. The foresters' problem, of course, has been that "progress"—in the form of automobiles, railroads, snowmobiles, lodges, summer homes, ski lifts, off-road vehicles, bicycles, motorcycles, recreational vehicles, and electric generators—has strongly intruded upon the silence and beauty of the national forests in the Southwest and elsewhere.

|

| Figure 36.—Summer house, Santa Fe National Forest, early 1920's. |

Ambivalence to Recreation

There was some apathy, or ambivalence, if not antipathy in the Forest Service in the Southwest at first toward recreation as a legitimate use of forest resources. Some foresters contended that areas subject to heavy applications for recreational or camp use should be eliminated from the National Forest System. Others began to believe that the Forest Service must accommodate urban visitors, in improved campgrounds or other facilities, as a means of controlling ingress into the wilderness and thereby protecting the natural environment. Aldo Leopold fought for the dedication of the Gila as a permanent wilderness hunting ground, and he advised establishing a policy of no roads in at least one area of forest in each of the Rocky Mountain States. Still others, including Arthur Ringland, first Southwestern District (Region) Forester, saw that efforts by the Forest Service to accommodate tourists and visitors would be an important way to inform the public of the work of the Forest Service and to "win friends and influence people." [7]

|

| Figure 37.—Moquitch Hunting Camp, with tents and stoves for rent. |

The Forest Service's understanding of what recreation is and its response to public needs have necessarily changed over time. The Southwestern Region has generally been highly responsive to public recreational needs, initiating programs and building facilities for recreational use. The region is richly endowed in its range of recreational natural resources, including snow-capped peaks, deep wooded forests, wilderness, scenic waterways and vistas, canyons, and desert.

The Southern Pacific Railroad, among others, recognized the special beauty of the Southwest and capitalized upon it by promoting tourism, particularly along the so-called Apache Trail running from Phoenix to the Roosevelt Dam. William Bass began promoting tourism along the South Rim of the Grand Canyon in the 1890's. He built a primitive road from Ashfork to the rim in 1890 and began constructing another from Williams in 1891. He built a nine-room guest house on the newly completed rail line to the Grand Canyon at "Bass Siding" about 1901; from there, he guided visitors and hunters into the Grand Canyon and to the North Rim. Bass's "white house" continued in intermittent use into the 1960's, when it was razed by the Forest Service. The Atlantic & Pacific Railroad began to operate a stage line from the rail line in Flagstaff to the Grand Canyon in 1892. The first stage left Flagstaff on May 26, 1892, and arrived at the site of what became the Grandview Hotel 12 uncomfortable hours later. Stage service closed in 1901, when the railroad reached the Grand Canyon. [8]

|

| Figure 38.—Hunters checking in at the ranger station in Ryan, AZ, the day before hunting season opens, early 1930's. |

Arthur Ringland, who was keenly aware of the public attractiveness of such areas as the Grand Canyon, provided fire protection services at the Grand Canyon Monument in 1909, erected sign boards with descriptive information at the El Tovar Hotel, and had guide maps printed for distribution to the thousands of tourists who visited the Grand Canyon. [9] In 1910, Harper's Weekly heralded the developing profile of recreation in the national forests and noted that there was a concentration of activity and attention in the West and Southwest. The approximately 406,775 visitors to the national forests in 1909 trade it clear that national forests are "fast becoming great national playgrounds for the people." [10] Although remote from large population centers, southwestern forests attracted many visitors.

|

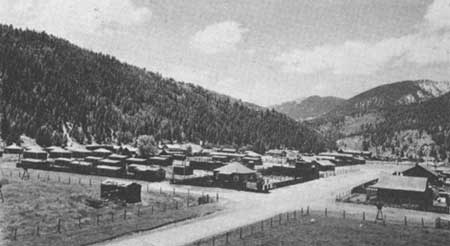

| Figure 39.—The summer resort town of Red River, NM, near the Carson National Forest, 1939. |

"The 21,000 persons who went into the Coconino Forest, Arizona, during 1909 went to camp or enjoy the scenery..." explained the editors. Among the great attractions of the Southwest, the article noted the Gila Cliff Dwellings, "an extensive remains of a prehistoric race in New Mexico, ... the unsurpassed Grand Canyon of the Colorado in Arizona ... and ... a group of prehistoric ruins in the Tonto Forest in Arizona." The recreational role of the forest rangers is alluded to as being to "point out the best site for a camper and the easiest route." And the dramatic conclusion was that "the day of the wilderness, of the savage, of the pioneer is passing" and the day of the "National Forests as productive resources and as National Parks" is approaching. [11]

|

| Figure 40.—Patio of Rancho Real, a guest ranch at Jemez Springs, NM, adjoining the Santa Fe National Forest, about 1940. |

Recognition of Recreation Came

Slowly

The approach of recreation as a significant factor in the administration of the national forests came slowly. The first congressional recognition of the role of recreation in or adjacent to the forest reserves came in 1899, when the Secretary of the Interior received authorization to rent or lease forest reserve grounds adjacent to "mineral, medicinal, or other springs" for sanitariums or hotels "where the public is accustomed or desires to frequent, for health or pleasure." [12] In 1906, "An Act for the Preservation of American Antiquities" provided for the protection of sites and ruins on public lands, but there was no appropriated funding for that purpose. In 1907, in a backhanded recognition of the recreational function of the national forests, Congress provided for the collection and deposit of fees for hunting, fishing, or camping on National Forest System lands. [13]

At the prodding of Theodore Roosevelt, Congress designated the Grand Canyon as a national monument in 1905, and subsequent Congressional bills and public interest proposed establishing the Grand Canyon as a national park. The recreational benefits of such a park were primary considerations for its establishment, and although the Grand Canyon was not transferred to the Department of the Interior until 1919, bills recommending such action appeared in Congress as early as 1910. On February 26, 1919, the act creating the Grand Canyon National Park was approved. More than 650,000 acres were transferred from the Kaibab and Tusayan National Forests to the park. [14] It seems that the transfer had the approval of Southwestern Region personnel, who, as was true with Forest Service personnel elsewhere, remained uncomfortable with the idea that recreation was an important or primary use of national forest resources.

|

| Figure 41.—A family enjoying an all-day ride into the Pecos Wilderness Area, Santa Fe National Forest, 1957. |

Trail Development

With the establishment of the forest reserves, the Forest Service undertook an ambitious trail development program aimed at meeting its administrative needs. Hiking trails developed inadvertently within the forests when the public began to use fire-breaks and administrative trails as hiking paths. By 1911, however, several ranger districts had begun to mark trails for the public, particularly in the area of the Grand Canyon. In areas adjacent to cities, such as Tucson, Flagstaff, Taos, and Albuquerque, the Forest Service made serious efforts to accommodate the interests of local citizens in having access to and using nearby forest areas for hiking, fishing, and camping. For example, the Arizona Democrat announced in 1909 that the Forest Service had "set aside" an area comprising the canyon running from Schulz's Pass to the county road, and including timber country west of Eldon and east of Flagstaff, "for the benefit of the residents of Flagstaff, Arizona, and in order to provide a small scenic or recreation forest in the vicinity." [15] For the Coronado, a joint effort in 1911 between the Forest Service and the Tucson Chamber of Commerce (each contributing $500) produced a hiking trail

which branches off the old Sabino trail at Pinchot Park and Pillows Pine Ridge, connecting with the old Soldiers Trail in the vicinity of Burned Cabin. The trail is about six miles in length and will be known as Pine Ridge Trail. The object of this trail is to make the attractive camping spots in which the Catalinas abound, more accessible to residents of Tucson. [16]

|

| Figure 42.—A family camping out at Whitewater Canyon, Gila National Forest. |

In 1913, the year after Arizona and New Mexico were admitted as States to the Union, the Southwestern Region established an area known as the Oak Creek Public Use Area on the Coconino National Forest, with specifications and plans for recreational use and development. The following year, the Secretary of Agriculture set aside 17,670 acres in the Oak Creek area as a special project for "scenic, fishing, and other recreation values." [17] Also, in 1913, the Southwestern Region cooperated with the State game and fish departments of Arizona and New Mexico in preparing and distributing pocket-sized cards with game laws and rules for fire protection. Six of the forests in the region also cooperated with the respective State game and fish departments in restocking trout streams. [18]

|

| Figure 43.—Picnickers at the Doc Long Picnic Ground shelter, Cibola National Forest, 1960. |

Bandelier National Monument

In July 1915, Arthur Ringland joined Will Barnes, chief of grazing of the Forest Service, and Don Johnson, forest supervisor of the Santa Fe National Forest, in an inspection of the Jemez Division on the upper Rio Grande. They particularly examined the canyon of the Rito del los Frijoles, which holds the remarkable pre-historic cliff dwellings, the more modern Tyuonyi and Cochiti pueblos (which were abandoned only in the 16th century), the stone lions of the Cochiti, and the Painted Caves. They recommended that the entire canyon area, comprising some 27,000 acres, be declared a national monument under the authority of the American Antiquities Act of June 3, 1906. Barnes and Judge Abbot of Santa Fe, who had the only cabin in the canyon, advised naming the monument for Adolph F. Bandelier, who had died March 18, 1914. Bandelier, who was born in Switzerland, came to New Mexico as the first fellow of the Archaeological Institute of America and spent 5 years exploring New Mexico and Arizona. His publications became the foundation for subsequent archeological and ethnological studies of the region. The Bandelier National Monument was established by presidential proclamation on February 11, 1916. [19]

It is clear that in the early years the Forest Service in the Southwestern Region was generally responsive to the recreational needs of local inhabitants, but it is also clear that those needs were minimal and that well into the 1920's recreation was considered by the region as strictly a "secondary function."

At the advent of World War I, the forests of the Southwest were relatively remote and inaccessible except to local inhabitants. Tourism had really not begun; the automobile and paved roads were virtually nonexistent in the region, and urban growth was quite modest. The total population of New Mexico in 1910 was 122,000, and Arizona boasted 113,000, with most of the population native Hispanic and Indian, and largely rural. The later increase in recreational uses of the national forests in the Southwest derived from the increase in urban populations, the advent of the automobile, and, most especially after World War II, the improvement of roads and the construction of interstate highways, making the region accessible to the general American public.

Portending this development, a New Mexico author, Ralph Twichell, wrote in 1917:

In addition to the purely economic resources of the New Mexico forests, they have a large and increasing value in the attractions which they offer to travelers, sportsmen, and health-seekers and in their increasing popularity with the people of New Mexico and adjacent states as a location for summer homes. This value for travel, sport, and recreation is largely dependent on a proper preservation of their scenic beauty, the development of roads and trails to make them accessible to the public, the protection of their historical and archaeological monuments and ruins, and the conservation of their fish and game. It is the definite aim of the forest service to accomplish these ends, and to encourage the full use of forests for purposes of recreation and public health. Few people are aware of the delightful climate, the extraordinary scenery, the wealth of historical and archaeological interest, and the facilities for sport, rest, and recreation which are offered them in the mountains of New Mexico. In fact, many people who have seen New Mexico only from the transcontinental trains have the impression that it is largely desert and quite without forests of any description. This is because the railroads, in order to avoid grades, naturally avoid the mountain ranges and seek the lowest elevations.

The future will see a greater appreciation of the possibilities of the New Mexico forests as a summer playground, and together with their steadily developing economic resources, will enable them to contribute an increasing share of the well-being and prosperity of the State. The Alamo, Gila, Datil, Manzano, Carson, and Chiricahua comprise the national forests of New Mexico. [20]

|

| Figure 44.—Entrance sign for a nature trail, Coronado National Forest. |

Twichell perhaps did not foresee the enormous impact of the automobile and the advent of winter sports, especially skiing.

Private entrepreneurs like J.W. Weatherford became aware early of opportunities created by the automobile. In 1916, Weatherford secured a permit to build a private road from Flagstaff northward near the San Francisco Peaks toward the Grand Canyon. A second permit issued in 1920 to Weatherford's San Francisco Mountain Scenic Boulevard Company provided that 15 years from that date, or at intervals of 5 years thereafter, the road should be surrendered back to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, if demanded, upon payment for the physical improvements. Construction began about 1919, and the road was completed in 1926. It operated as a toll road until 1934, when it was forced to suspend maintenance because of declining revenues. After extended study and negotiations, the toll road permit was terminated by the Forest Service in 1938 upon payment of $15,500 to Mrs. Flora Finne, Weatherford's sister and acting president of the San Francisco Mountain Scenic Boulevard Company. The toll house, built in 1929, continued in private use under special permit fees as a residence until the house passed into the private ownership of Dr. and Mrs. M.M. Zack in 1959. Although a financial failure, Weatherford's venture indicated very early the recreation potential of the region made available by the automobile. [21]

|

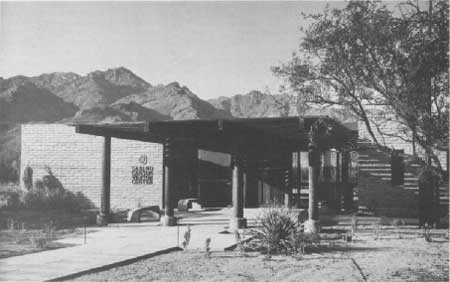

| Figure 45.—Sabino Canyon Visitor Center, with exhibits explaining the vegetation types in the surrounding mountains, Coronado National Forest. |

Recreational Planning Begins

Post-World War I prosperity expanded the travel and recreational horizons of Americans tremendously. In the 1920's, planning for recreational use became a part of the comprehensive plan for each forest in the Southwestern Region. Recreational objectives announced by the regional office in 1921 encouraged each forester to assist community authorities in locating, planning, and developing municipal playgrounds and parks, and also to improve campgrounds in designated areas. Recreational plans also were established to encourage the allocation of suitable forest areas for summer cottages, camping areas, hotels, and voluntary agency camps. Authority for this derived from a 1915 act of Congress that specified such uses for recreation, public convenience, or safety. [22]

The region prepared public information folders entitled "Recreation in the Southwest" and "Sunshine Recreation of a Nation." The Carson National Forest made a concerted effort to promote public interest and awareness of the recreation potential of the forest through public lectures and the preparation of road and trail maps. The Coconino foresters developed camp sites along Highway 66 and built improved camping areas at Oak Creek, Twin Springs, and Mormon Lake. Public information programs were also developed in the Crook, Gila, and Lincoln National Forests. [23] Perhaps indicative of the new recreation consciousness, the Forest Service began keeping data and counts on recreational uses and visits to the national forests in 1924. Also that year, foresters, particularly Arthur C. Ringland, began participating in the National Conference on Outdoor Recreation.

|

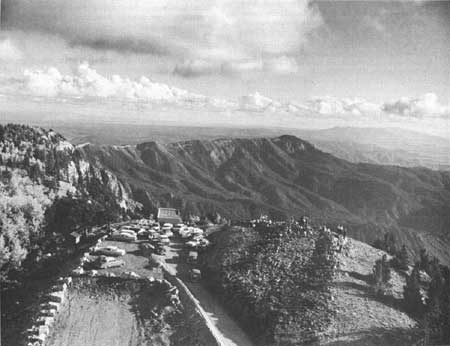

| Figure 46.—Sandia Crest lookout, Cibola National Forest, late 1950's. |

Ringland had just completed service with President Herbert Hoover's relief administrations. President Calvin Coolidge called the National Conference on Outdoor Recreation into session upon the advice of his cabinet to formulate national outdoor recreation policies. On May 22, 1924, 309 delegates, representing 128 organizations, opened the conference in Washington, DC. Leon Kneipp served as executive secretary, and in 1925, he invited Ringland to take over the post so that he (Kneipp) could return to his regular duties with the Forest Service. The conference initiated comprehensive surveys of recreational facilities and resources of the nation, including the Federal lands. Legislative initiatives included an act allowing States, counties, and municipalities to acquire public lands for recreation and park purposes, a migratory bird bill, the Woodruff-McNary Bill for forest acquisition, and the McSweeney-McNary Bill for forest and biological research. [24]

|

| Figure 47.—Map of the National Forest System in the Southwest, Coronado National Forest. |

The conference was dissolved in 1929 but had far-reaching impacts on the management of recreational resources throughout the Nation, as well as in the Southwestern Region. A meeting of New Mexico State and Federal officials in Santa Fe in August 1929 considered future recreational developments on a broad statewide basis. The stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing depression put these activities, along with most leisure-recreation usages of the national forests in the Southwest, on temporary hold. Curiously, by the mid-1930's, the Great Depression also brought new opportunities to expand recreational programs and facilities. Under New Deal programs, the number of dollars spent on recreational improvements in the Southwestern Region increased substantially, while the number of visitors doubled.

CCC Improves Recreational

Facilities

Franklin Delano Roosevelt inaugurated his New Deal for America on March 4, 1933. The New Deal increased public expenditures for public services, welfare programs, and public construction, and provided government-insured loans to agriculture and business. Unemployment rose to 23.6 percent of the labor force in 1932 and to a high of 24.9 percent in 1933. Congress approved and Roosevelt implemented the Agricultural Adjustment Act, the Public Works Administration, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, the National Industrial Recovery Act, and, perhaps of most importance to the Southwestern Region, the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). [25] The Bankhead-Jones Act provided the authority for the acquisition of the national grasslands in Oklahoma and Texas, and the CCC became the primary agent in the improvement of recreational facilities and access to the forests of the Southwest.

|

| Figure 48.—Hikers on a wilderness trail in Mt. Baldy Primitive Area, Apache National Forest. |

The CCC provided employment opportunities for unemployed young men between the ages of 17 and 23 within a loose framework of military discipline under the direction of the U.S. Army. Most of that labor was assigned to work projects in the State and national forests and parks, under the authority of the forest and park supervisors. Young foresters, themselves unemployed or potentially unemployed college graduates, directed CCC crews in the construction and development of camp and picnic grounds, trails, access roads, ski areas, lakes, group shelters, and other special recreation facilities, many of which are in use today.

Between 1933 and 1938, the Sabino Canyon Recreation Area on the Coronado National Forest was developed by CCC labor groups and occasional WPA (Works Progress Administration) crews. Workers extended the road that had terminated at the Lowell Ranger Station into the canyon and built nine bridges in the process. Picnic units were established with wooden tables, which apparently began to be used by visitors for firewood, whereupon the Forest Service began installing concrete tables. By 1940, tables, restrooms, garbage cans, swings, and visitor registers were available for the almost 100,000 annual visitors. Ten years earlier, visitors had been few. A dam and lake were also built on the lower Sabino, which attracted many fishermen. Located only 13 miles from downtown Tucson, the Sabino Canyon facilities are extremely important to the quality of life for city residents. Although additional recreation areas lave been provided in the Santa Catalina District, of which the Sabino Canyon is a part, projected population growth of Tucson to 1.3 million by the year 2000 forebodes enormous pressures on neighboring recreational resources. [26]

|

| Figure 49.—Campers at Sheeps Crossing Forest Camp, Apache National Forest, 1960. |

Recreational Planning Takes

Precedence

The regional forester reported in 1934 that for the first time, recreational planning and development took precedence over all other Southwestern Region programs. The "Recreation Improvement Handbook," developed by the region in 1933 and updated in following years, urged concentrated efforts in developing proven and more important campgrounds and emphasized providing sanitation facilities, tables, benches, and fireplaces. Planning and construction was to emphasize natural beauty and the use of native materials. Substantial recreational improvements were made on the Gila National Forest, on the Sabino of the Coronado, on Sandia Crest and the Juan Tabo picnic area in the Sandia Mountains, and at White Horse Lake on the Kaibab. Planning and construction also began for a winter sports area, the Agua Piedra, on the Carson National Forest. [27] All forests reported some improvements in recreation facilities, with those closest to population centers being given the greatest priority.

Many ranger stations and supporting facilities were built by CCC labor in the 1930's, and some remain in use. These administrative units characteristically included an office, parking area, flagpole, service court (garage and fuel storage), a warehouse for general and fire equipment storage, a machine and blacksmith shop, and a barn and corral. Residences and dormitories were sometimes built for rangers and crews. Road building, which had great recreational impact, also was a major occupation of the CCC crews, as were shelters, picnic grounds, and overnight campgrounds. Extant examples of CCC construction include the Monjeau Lookout Tower, the Mesa barn, and the Cedar Creek picnic shelter on the Lincoln National Forest. [28]

The 1941 inspection report, "Recreation and Lands Activities," of the Apache National Forest, praised the work of the CCC:

While on the Apache, we saw campgrounds on South Fork, those near Creer, Sheep Crossing, Buffalo Crossing, Big Lake, East Fork, and those on the Blue. All of them were clean. In talking with the Apache personnel, including the Supervisor, Voight, Henry McDaniels, and several of the CCC foremen, I got the impression that the entire force was trying conscientiously to keep the recreation areas sanitary and presentable. [29]

Tremendous improvement had occurred since the 1939 unfavorable report of John Sieker, assistant recreation chief from the Washington office, and the inspectors believed that the "Apache [National Forest] has taken full advantage of CCC and of other resources in maintaining these areas." [30]

CCC roads and facilities were used by increasing numbers of visitors, despite the continuing depression. In fact, perhaps because of the depression and the relatively low cost of forest recreation, recreational uses of the national forests expanded rapidly. Nationally, total recreation visits surged from 6.9 million in 1930 to 18 million in 1941. (See table 10.) An interesting indicator of the surge in recreation visits to the national forests is the report by Osborn Brown, the lookout at the Jacob Lookout Tower on the north Kaibab. This is an area not easily accessible even today. Brown reported that 1,271 visitors registered at the tower during the period May 5 to August 28, 1940, that most of them climbed the 100-foot tower, and that another 100 or so probably visited without registering. In order of origin, the most visitors came from Utah, then California, Arizona, Illinois, and Nebraska. Brown distributed 700 descriptive folders of the Kaibab to the visitors. [31] This rather obscure information produced some very significant conclusions for Forest Service policymakers.

Table 10. Nationwide recreation use of the National Forest System

| Calendar year | Camp-grounds | Winter sports sites | Other special use | Other developed sites | Wilderness/ primitive | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visits (thousands) per calendar year (1924-1964) | |||||||

| 1924 | 1,588.5 | - | 1,200.3 | 1,871.5 | - | - | 4,660.3 |

| 1934 | 2,343.1 | - | 1,627.5 | 4,610.2 | - | - | 8,580.8 |

| 1944 | 1,246.8 | 287.4 | 1,262.5 | 2,051.1 | 50.0 | 2,254.2 | 7,152.0 |

| 1954 | 5,806.1 | 2,362.4 | 4,490.8 | 11,467.8 | 395.8 | 15,781.0 | 40,303.9 |

| 1964 | 14,152.1 | 7,911.8 | 8,185.3 | 11,476.9 | 973.8 | 81,062.4 | 133,762.3 |

| Visitor-days* (thousands) per calendar year (1974-1984) | |||||||

| 1974 | 35,677.9 | 7,722.0 | 17,103.4 | 9,455.0 | 6,743.2 | 116,214.3 | 192,915.8 |

| 1984 | 55,454.0 | 13,900.4 | 16,755.6 | 9,392.4 | 10,209.3 | 135,085.5 | 227,553.9 |

*Recreational use of National Forest land and water

which aggregates 12 person-hours. May entail 1 person for 12 hours, 12

persons for 1 hour, or any equivalent combination of individual or group

use, either continuous or intermittent. "Other special use" denotes

hotels, resorts, and recreational residences.

Source: Director of recreation, Southwestern Region.

As Walter G. Mann, then Forest Supervisor, explained:

This is a very interesting report, and shows the public contacts and opportunities of putting across Forest Service policies and objectives for the traveling public at stations of contact like this.

When we consider that 1,271 traveling people from 38 states, the District of Columbia and 6 foreign countries, went to the trouble to climb a 100-foot tower to look at our country, and then have the lookout give them a talk on our work, we should feel flattered. [32]

Mann was enormously impressed with the potential for "selling" the national forest idea, and he also was concerned that wherever the public gathers in the national forests, there should be adequate improvements—"two-room guard cabin, garage, and toilets" instead of no toilets and a lookout living in a tent with his car parked under a tree. [33]

War Slows Recreation Activity

The growing activity and interest in recreation collapsed with the attack on Pearl Harbor and American entry into World War II. Forestry personnel volunteered or were drafted for military service, and naturally, visitors to the forests nationwide declined from 18 million in 1941 to 6 and 7 million in 1943 and 1944, respectively. Among other things, an effort to conserve personnel in the forests produced a "streamlined" recreation report. The old form 833 gave way to the new form 446, with adverse results. Acting Regional Forester George W. Kimball explained that although "the Recreation Visits report has been streamlined for the duration," the correct preparation of the new form 446 "took considerably more time and care than it did when we were using the 'old' form." [34] Thus the base data and the time involved in counting became different and more cumbersome. That, of course, was only the beginning of the new "paper war" that was waged ever more intently in future decades as new copy, typing, and reproduction technology were developed.

Many things changed after the war, and recreation changed substantially. By 1946, recreation visits to the national forests nationwide had recovered to the 1941 prewar levels of 18 million, and by 1961, exceeded 100 million—a fivefold increase in 15 years. (See table 11.)

Table 11. Nationwide recreation visits to the national forests (1946-61)

| Calendar year | Camp-grounds | Picnic sites | Winter sports sites | Hotels and resorts | Recreation residences | Other forest areas | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1946 | 3,055,114 | 4,458,748 | 1,249,200 | 2,286,107 | 713,380 | 6,478,128 | 18,240,677 |

| 1947 | 3,518,147 | 5,262,600 | 1,725,675 | 2,110,406 | 535,978 | 8,177,945 | 21,330,751 |

| 1948 | 3,424,088 | 6,682,158 | 2,284,943 | 1,928,756 | 572,499 | 9,118,520 | 24,010,964 |

| 1949 | 3,837,010 | 7,659,234 | 1,712,607 | 1,929,597 | 615,242 | 10,326,565 | 26,080,255 |

| 1950 | 3,858,845 | 7,577,565 | 1,504,575 | 1,902,140 | 627,481 | 11,897,181 | 27,367,797 |

| 1951 | 4,140,866 | 8,669,234 | 1,929,270 | 2,133,674 | 636,173 | 12,440,928 | 29,950,252 |

| 1952 | 4,527,979 | 9,515,926 | 1,758,073 | 2,500,196 | 670,632 | 14,034,079 | 33,006,885 |

| 1953 | 4,810,341 | 10,335,910 | 1,944,193 | 2,564,219 | 758,493 | 14,989,894 | 35,403,050 |

| 1954 | 5,806,130 | 11,467,849 | 2,362,420 | 2,990,264 | 864,568 | 15,812,806 | 40,304,037 |

| 1955 | 6,796,706 | 12,418,342 | 2,977,220 | 3,230,860 | 863,332 | 19,426,408 | 45,712,868 |

| 1956 | 7,204,986 | 14,667,226 | 3,040,513 | 4,128,912 | 851,474 | 22,662,973 | 52,556,084 |

| 1957 | 8,352,360 | 16,138,508 | 3,158,675 | 4,211,682 | 828,550 | 28,267,498 | 60,957,273 |

| 1958 | 9,324,700 | 17,845,200 | 4,127,000 | 4,117,300 | 850,400 | 32,184,900 | 68,449,500 |

| 1959 | 9,944,800 | 19,283,300 | 4,184,100 | 4,597,400 | 896,300 | 42,605,100 | 81,521,000 |

| 1960 | 10,878,000 | 19,800,800 | 4,706,800 | 4,575,500 | 1,114,200 | 51,519,200 | 92,594,500 |

| 1961 | 11,835,100 | 20,456,800 | 4,478,300 | 5,309,900 | 1,175,600 | 58,656,800 | 101,912,500 |

Source: Director of recreation, Southwestern Region.

Postwar Increase In Recreation

In a very real sense, the advent of modern recreation in the national forests, and certainly in the Southwestern Region, dates from the post-World War II era. The Southwestern Region, for example, had more than 12 million recreation visits in 1963, as compared to a few hundred thousand in 1941 (tables 12 and 13). The surge of tourists and recreationists in the postwar era was distinctly a mixed blessing for the Forest Service, which in the Southwestern Region and elsewhere was generally unable to cope. Inflation, demobilization, and economic uncertainties in the decade after the war resulted in fewer dollars available to the forests for recreation. By 1961, CCC-constructed facilities and campgrounds had become painfully inadequate. Opportunities in private industry distracted a generation of foresters from public service, and the more conservative fiscal policies of the Eisenhower years (1952-60) discouraged the renewal of CCC-type programs that had so benefited forestry work. Booming economic conditions and the continuance of the military draft would have likely prevented such programs from working, even had they been funded by Congress.

Table 12. Total recreational use of national forests in Arizona

| Year | Apache- Sitgreaves* |

Coconino | Coronado | Kaibab | Prescott | Tonto | Total Arizona |

Total region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visits (thousands) per calendar year (1939-1964) | ||||||||

| 1939 | 20.6/15.5 | 66.5 | 123.6 | 41.4 | 70.9 | 90.4 | 428.9 | 817.8 |

| 1940 | 31.5/19.8 | 269.8 | 153.1 | 50.9 | 210.9 | 89.7 | 825.7 | 1,336.4 |

| 1941 | 42.9/22.7 | 207.0 | 189.9 | 93.5 | 465.0 | 107.8 | 1,128.8 | 1,696.4 |

| 1942 | 35.8/17.0 | 294.0 | 112.1 | 65.4 | 208.5 | 54.9 | 787.7 | 1,177.3 |

| 1943 | 39.4/22.7 | 222.5 | 96.2 | 32.6 | 130.5 | 58.1 | 602.0 | 888.6 |

| 1944 | 36.2/11.8 | 175.1 | 98.1 | 34.8 | 125.2 | 64.6 | 545.8 | 842.9 |

| 1945 | 32.1/11.1 | 218.9 | 110.5 | 62.5 | 164.5 | 107.8 | 707.4 | 1,033.0 |

| 1946 | 32.5/10.3 | 610.0 | 136.3 | 154.7 | 211.1 | 104.9 | 1,259.8 | 1,716.9 |

| 1947 | 27.5/11.0 | 903.8 | 192.8 | 897.2 | 215.7 | 238.0 | 2,486.0 | 3,037.0 |

| 1948 | 27.9/11.9 | 985.0 | 421.8 | 860.7 | 229.6 | 256.5 | 2,793.4 | 3,479.6 |

| 1949 | 30.1/25.3 | 1,234.5 | 429.2 | 229.6 | 247.2 | 324.5 | 2,520.4 | 3,348.8 |

| 1950 | 35.1/27.3 | 1,322.9 | 4,122.2 | 248.0 | 273.1 | 334.6 | 6,363.2 | 8,208.1 |

| 1951 | 52.2/27.9 | 1,461.1 | 453.7 | 260.6 | 277.2 | 354.3 | 2,887.0 | 4,381.4 |

| 1952 | 51.1/36.7 | 2,049.0 | 491.3 | 279.5 | 2,198.4 | 378.4 | 5,484.4 | 8,744.6 |

| 1953 | 45.9/38.8 | 2,122.1 | 589.8 | 286.8 | 1,199.2 | 1,373.3 | 5,655.4 | 7,630.4 |

| 1954 | 552.9/37.9 | 2,860.6 | 607.2 | 2,023.6 | 1,223.5 | 1,516.0 | 8,821.7 | 12,318.2 |

| 1955 | 600.3/242.9 | 4,439.3 | 660.7 | 279.0 | 2,500.4 | 1,726.6 | 10,449.2 | 14,080.8 |

| 1956 | 536.0/234.0 | 4,959.0 | 907.0 | 1,132.0 | 1,810.0 | 1,859.0 | 11,437.0 | 15,366.7 |

| 1957 | 558.0/948.4 | 5,245.7 | 993.8 | 1,179.9 | 2,100.2 | 2,016.5 | 13,042.5 | 17,744.4 |

| 1958 | 197.6/71.2 | 424.3 | 790.3 | 139.3 | 438.9 | 1,411.5 | 3,472.1 | 5,638.0 |

| 1959 | 281.7/118.8 | 449.6 | 1,156.4 | 183.1 | 479.6 | 2,043.0 | 4,712.2 | 7,751.2 |

| 1960 | 285.2/128.5 | 584.3 | 1,274.7 | 210.5 | 501.1 | 2,019.0 | 5,003.3 | 8,194.2 |

| 1961 | 310.1/157.9 | 612.9 | 1,386.9 | 199.9 | 514.4 | 2,011.2 | 5,193.3 | 8,585.9 |

| 1962 | 341.0/173.5 | 1,313.7 | 1,568.5 | 299.4 | 506.2 | 2,103.5 | 6,305.8 | 10,188.2 |

| 1963 | 502.3/236.7 | 1,700.1 | 1,675.1 | 412.8 | 550.9 | 2,388.6 | 7,466.5 | 12,399.1 |

| 1964 | 491.5/301.9 | 1,860.0 | 1,463.9 | 680.0 | 578.9 | 2,361.0 | 7,737.2 | 13,495.4 |

| Visitor-days (thousands) per calendar year (1965-1984) | ||||||||

| 1965 | 604.9/486.7 | 1,369.5 | 77.7 | 997.8 | 468.3 | 2,372.2 | 6,377.1 | 8,797.1 |

| 1966 | 618.0/225.4 | 1,369.5 | 927.0 | 906.7 | 433.8 | 1,984.3 | 6,464.7 | 9,061.9 |

| 1967 | 624.9/259.5 | 874.8 | 926.9 | 906.4 | 456.6 | 1,966.6 | 6,015.7 | 7,995.8 |

| 1968 | 611.5/290.8 | 922.2 | 919.0 | 900.6 | 645.9 | 2,005.9 | 6,295.9 | 8,742.7 |

| 1969 | 729.1/359.6 | 966.4 | 1,119.7 | 979.0 | 629.5 | 2,033.6 | 6,816.9 | 9,829.1 |

| 1970 | 920.7/699.6 | 1,167.3 | 1,397.0 | 1,123.7 | 715.2 | 1,914.2 | 7,937.7 | 11,300.8 |

| 1971 | 1,536.7 | 1,046.1 | 1,432.2 | 1,146.9 | 642.5 | 2,500.9 | 8,305.3 | 11,677.9 |

| 1972 | 1,514.3 | 1,304.9 | 1,425.6 | 1,197.7 | 743.9 | 2,708.9 | 8,895.3 | 12,402.9 |

| 1973 | 1,883.5 | 1,849.7 | 1,723.8 | 1,195.7 | 802.6 | 2,955.1 | 10,412.4 | 14,169.3 |

| 1974 | 2,016.3 | 1,708.7 | 1,606.6 | 1,328.7 | 729.9 | 3,116.1 | 10,506.3 | 14,538.1 |

| 1975 | 1,858.0 | 1,742.6 | 1,879.7 | 1,254.2 | 781.0 | 3,931.5 | 11,447.0 | 15,729.8 |

| 1976 | 1,878.3 | 1,884.5 | 2,116.8 | 1,297.6 | 689.9 | 4,016.9 | 11,884.0 | 16,481.2 |

| 1977 | 2,133.6 | 1,906.8 | 2,059.4 | 1,255.9 | 837.5 | 4,641.7 | 12,834.9 | 18,233.3 |

| 1978 | 2,230.7 | 1,787.6 | 2,075.3 | 1,078.9 | 854.6 | 3,789.3 | 11,816.4 | 18,072.5 |

| 1979 | 2,604.7 | 2,623.2 | 2,315.2 | 1,071.1 | 1,042.9 | 4,186.3 | 13,843.4 | 19,505.8 |

| 1980 | 2,771.1 | 3,721.1 | 2,489.6 | 1,141.5 | 1,063.7 | 6,564.5 | 17,751.5 | 23,704.8 |

| 1981 | 2,485.5 | 4,957.3 | 2,584.2 | 1,106.8 | 1,034.1 | 5,669.7 | 17,837.6 | 24,115.4 |

| 1982 | 2,208.2 | 4,863.4 | 2,155.3 | 1,171.4 | 1,005.6 | 5,528.5 | 16,932.4 | 23,635.8 |

| 1983 | 1,886.5 | 4,248.2 | 2,299.6 | 1,090.0 | 1042.7 | 6,018.3 | 16,585.3 | 23,596.6 |

| 1984 | 1,795.5 | 4,003.7 | 2,214.7 | 963.0 | 954.0 | 6,450.3 | 16,381.2 | 22,943.4 |

*Two forests now administered by one supervisor.

Source: Director of recreation, Southwestern Region.

Table 13. Total recreational use of national

forests in New Mexico

| Year | Carson | Cibola | Gila | Lincoln | Santa Fe | Total New Mexico |

Total region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visits (thousands) per calendar year (1939-1964) | |||||||

| 1939 | 62.0 | 116.6 | 29.7 | 93.9 | 86.7 | 388.9 | 817.8 |

| 1940 | 69.3 | 202.4 | 41.5 | 115.2 | 182.3 | 510.7 | 1,336.4 |

| 1941 | 50.4 | 221.2 | 81.2 | 140.1 | 74.7 | 567.6 | 1,696.4 |

| 1942 | 43.9 | 154.2 | 58.9 | 80.7 | 51.9 | 389.6 | 1,177.3 |

| 1943 | 32.5 | 76.5 | 58.7 | 74.6 | 44.3 | 286.6 | 888.6 |

| 1944 | 33.7 | 105.4 | 31.2 | 81.4 | 45.4 | 297.1 | 842.9 |

| 1945 | 39.4 | 114.6 | 30.7 | 92.7 | 48.2 | 325.6 | 1,033.0 |

| 1946 | 56.6 | 157.4 | 34.8 | 140.2 | 68.1 | 457.1 | 1,716.9 |

| 1947 | 81.0 | 198.1 | 36.5 | 157.2 | 78.2 | 551.0 | 3,037.0 |

| 1948 | 87.3 | 245.2 | 42.1 | 183.3 | 128.3 | 686.2 | 3,479.6 |

| 1949 | 179.6 | 278.1 | 41.7 | 182.4 | 146.6 | 828.4 | 3,348.8 |

| 1950 | 179.7 | 1,190.4 | 39.8 | 284.0 | 151.0 | 1,844.9 | 8,208.1 |

| 1951 | 322.8 | 590.1 | 40.1 | 403.1 | 138.3 | 1,494.4 | 4,381.4 |

| 1952 | 329.6 | 942.7 | 46.2 | 1,768.7 | 173.0 | 3,260.2 | 8,744.6 |

| 1953 | 333.2 | 1,110.9 | 63.6 | 187.3 | 280.0 | 1,975.0 | 7,630.4 |

| 1954 | 419.4 | 853.4 | 60.4 | 1,921.0 | 242.3 | 3,496.5 | 12,318.2 |

| 1955 | 450.1 | 913.2 | 70.6 | 1,937.6 | 260.1 | 3,671.6 | 14,080.8 |

| 1956 | 526.0 | 983.0 | 76.7 | 2,020.0 | 324.0 | 3,929.7 | 15,366.7 |

| 1957 | 807.0 | 1,112.3 | 137.5 | 2,221.9 | 423.2 | 4,701.9 | 17,744.4 |

| 1958 | 313.4 | 946.8 | 50.0 | 462.9 | 411.8 | 2,184.9 | 5,638.0 |

| 1959 | 377.3 | 1,053.5 | 63.2 | 887.8 | 663.2 | 3,045.0 | 7,751.2 |

| 1960 | 417.9 | 1,065.4 | 108.7 | 900.4 | 698.5 | 3,190.9 | 8,194.2 |

| 1961 | 394.2 | 1,084.5 | 133.3 | 1,035.8 | 744.8 | 3,392.6 | 8,585.9 |

| 1962 | 450.1 | 1,178.3 | 174.7 | 1,115.6 | 963.7 | 3,882.4 | 10,188.2 |

| 1963 | 760.9 | 1,419.9 | 246.6 | 1,365.1 | 1,138.1 | 4,930.6 | 12,399.1 |

| 1964 | 796.9 | 1,562.6 | 323.0 | 1,866.4 | 1,209.3 | 5,758.2 | 13,495.4 |

| Visitor-days (thousands) per calendar year (1965-1984) | |||||||

| 1965 | 345.9 | 985.7 | 469.3 | 483.6 | 135.5 | 2,420.0 | 8,797.1 |

| 1966 | 363.1 | 1,153.7 | 382.0 | 510.7 | 187.7 | 2,597.2 | 9,061.9 |

| 1967 | 305.5 | 976.9 | 231.3 | 324.4 | 142.1 | 1,980.2 | 7,995.8 |

| 1968 | 488.1 | 1,051.9 | 275.3 | 440.4 | 191.1 | 2,446.8 | 8,742.7 |

| 1969 | 640.3 | 1,446.7 | 286.7 | 425.7 | 212.8 | 3,012.2 | 9,829.1 |

| 1970 | 765.8 | 1,398.8 | 384.8 | 565.3 | 248.4 | 3,303.4 | 11,300.8 |

| 1971 | 635.3 | 685.4 | 370.9 | 1,069.8 | 611.2 | 3,372.6 | 11,677.9 |

| 1972 | 617.3 | 697.2 | 406.5 | 938.7 | 847.9 | 3,507.6 | 12,402.9 |

| 1973 | 678.2 | 727.2 | 451.9 | 895.8 | 1,003.8 | 3,756.9 | 14,169.3 |

| 1974 | 631.0 | 813.1 | 539.3 | 1,079.6 | 968.8 | 4,031.8 | 14,538.1 |

| 1975 | 582.0 | 839.8 | 653.1 | 843.7 | 1,364.2 | 4,282.8 | 15,729.8 |

| 1976 | 639.8 | 920.6 | 713.7 | 966.1 | 1,357.0 | 4,597.2 | 16,481.2 |

| 1977 | 689.4 | 1,110.9 | 972.9 | 1,059.0 | 1,566.2 | 5,398.4 | 18,233.3 |

| 1978 | 1,371.1 | 1,118.5 | 906.7 | 1,164.9 | 1,694.9 | 6,256.1 | 18,072.5 |

| 1979 | 899.1 | 1,008.6 | 943.3 | 1,057.4 | 1,754.0 | 5,662.4 | 19,505.8 |

| 1980 | 946.3 | 1,020.2 | 797.7 | 1,119.5 | 2,069.6 | 5,953.3 | 23,704.8 |

| 1981 | 961.6 | 1,114.9 | 855.9 | 1,094.4 | 2,251.0 | 6,277.8 | 24,115.4 |

| 1982 | 1,072.5 | 1,190.1 | 949.9 | 1,237.8 | 2,252.3 | 6,702.6 | 23,655.8 |

| 1983 | 1,348.7 | 1,283.3 | 857.6 | 1,137.4 | 2,384.3 | 7,011.3 | 23,596.6 |

| 1984 | 1,116.0 | 1,285.5 | 1,172.1 | 1,120.7 | 1,867.9 | 6,562.2 | 22,943.4 |

Source: Director of recreation, Southwestern Region.

As pressures from the growing ranks of visitors mounted in the Southwest, Forest Service personnel worked with limited resources to meet the growing demands. Staffers began placing winter sports areas under special use permits, began thinking in terms of landscape design for buildings, campgrounds, and vista points, and sought new sources of revenue for recreation projects. Pima County, AZ, placed $25,000 in a cooperative fund with the Forest Service for development of recreation areas in the Santa Catalina Mountains adjacent to Tucson. The Federal Bureau of Prisons agreed to provide prison camp labor to the Forest Service in the Santa Catalinas for recreation improvements. Although not the CCC, the program did provide much-needed workers. And for the first time, the Forest Service in the 1950's began to think of having recreational specialists for the forests and to charge fees to recreational users. [35]

Although pressures on public forest recreation areas in the Southwestern Region did not become as great in the early 1950's as they had in other regions, such as the Pacific Southwestern, Rocky Mountain, and Intermountain Regions, two major developments in the Southwestern Region presaged a time of rapid change. The first intimations of the growing migration into the "sunbelt" were becoming clear, and the development of winter sports began creating whole new dimensions in recreation activities in the national forests. All of the potential ski areas in Arizona and New Mexico were in or adjacent to national forest land. Even as these changes were occurring, the condition of recreational resources in the southwestern forests seemed to be worsening.

Development Lags

In 1954, the General Inspection Report of the Gila National Forest noted that facilities on the Gila were those developed by CCC labor and had not grown in pace with the increasing recreational load. "They, in fact, have gone in the opposite direction." [36] Moreover, while the inspectors believed that the staff spent their limited amount of money advantageously, very little staff time actually went to recreation. Staffers spent 10 percent of their time, rangers 35 percent, and assistant rangers and district guards 4 percent on recreational, wildlife, and land-use activities. [37]

Similarly, on the Coconino in 1958, inspectors found few recreation sites in acceptable condition from the standpoint of sanitation, maintenance, and area administration. "Coconino public recreation areas were not in creditable condition when inspected," the report concluded. Specifically, at Lake View, although fully occupied by tents and trailers, there were three or four tables for 15 family units and two "single-dual toilets" in poor condition. Fill dirt had eroded from the base of one unit, and nearby garbage cans were foul smelling and maggot-infested. The trailer that housed the concession operator seemed permanently placed with a drainline spilling onto the grounds. The report detailed unsatisfactory conditions at every public campground. [38] These were not very pretty pictures. Southwestern Region foresters had a serious recreation problem and a growing public relations problem on their hands.

Edward P. Cliff, then assistant chief of the Forest Service, informed the 47th Annual Conference of the International Association of Game, Fish, and Conservation Commissioners in Las Vegas, Nevada, on September 10, 1957, that from 1940 to 1957 recreation visits to the national forests rose from 16 million to 52.5 million. In the previous 2 years, he said, recreation visits increased from 40 million to 52.5 million. "As you know," he continued, "most of the campground, picnic area, and other recreational facilities on the national forests were installed in the 30's by the Civilian Conservation Corps. There has been little expansion since." [39] In January, he said, the U.S. Department of Agriculture released a 5-year National Forest Recreation Program—Part I of "Operation Outdoors" (table 14). Operation Outdoors was intended, he said, to provide forest-type recreation opportunities, which he defined as camping, picnicking, swimming, skiing, hiking, riding, wilderness travel, mountain climbing, hunting, and fishing. The Forest Service intended to keep facilities "simple and appropriate to the environment," and not to "conduct tours, give lectures, nor sponsor organized sports." Operation Outdoors was budgeted for $85 million, with over half going to restoration and new facilities. [40]

Table 14. Recreational use (thousands of visits) of national forests In the United States (1946-55)

| Forest Service Region | 1946 | 1950 | 1955 | Rate of increase (percent) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern | 755 | 1,196 | 1,863 | 148 |

| Rocky Mountain | 2,038 | 3,930 | 7,182 | 252 |

| Southwestern | 813 | 1,502 | 3,546 | 340 |

| Intermountain | 3,068 | 4,281 | 6,105 | 98 |

| California | 3,913 | 3,695 | 7,715 | 98 |

| Pacific Northwest | 2,186 | 3,078 | 5,186 | 138 |

| Eastern | 2,406 | 2,205 | 2,897 | 20 |

| Southern | 1,159 | 4,382 | 56,322 | 445 |

| Lake States | 1,812 | 2,826 | 4,464 | 146 |

| Alaska | 37 | 102 | 262 | 610 |

| Total United States | 18,187 | 27,297 | 45,542 | 250 |

Source: Operation Outdoors (Washington DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, 1957), p. 11.

Unfortunately, realities often interfere with aspirations, as was true in the case of Operation Outdoors. Appropriations failed to match budget plans. For fiscal year 1958, recreation land-use budgets for the Forest Service were scaled down from $115 million projected in the President's budget to $8.7 million approved by Congress. The Southwestern Region's appropriation was $830,000. Despite the cut, real appropriations to recreation exceeded by two and a half times the funds available in 1957. Operation Outdoors would begin, "but at a little slower pace. [41]

Recreation Specialists

Appointed

For the first time since the 1930's, this meant that, in the Southwestern Region and elsewhere, recreation specialists could be appointed for national forests with heavy recreation use, new data could be gathered from visitor questionnaires, landscape architects could be hired and trained, areas and facilities could be rehabilitated, and new forest recreation plans could be developed. [42] In August, $49,700 of the recreation funds appropriated to the Southwestern Region were withdrawn, as was a comparable amount from the road funds, which also had an impact on recreation. [43]

Despite these fiscal impediments, there was clear progress in Forest Service recreational planning and development, which inadvertently triggered conflicts of interest between the Forest Service and the National Park Service. In a lengthy memorandum in September 1957 to the Secretary of the Interior, Secretary of Agriculture Ezra Taft Benson addressed the problem. Benson recognized the conflict as in part stemming from the:

understandable desire on the part of the National Park Service to exercise leadership in the planning of recreation on public lands, and to cooperate with States and local agencies on recreation planning on their lands. The Act of June 23, 1936 (49 Stat. 1894) directs the National Park Service to undertake the planning and development work in Federal lands and to cooperate with State and local agencies, but all lands under the jurisdiction of this Department are exempted from the provisions of that Act.

Benson explained that recreation planning for National Forest System lands presented a different problem because they are managed for multiple use, and that job is logically one for the Forest Service. [44]

The Memorandum of Understanding of 1948, between the Bureau of Reclamation (Department of the Interior) and the Forest Service, required coordination and cooperation in the development of recreation management for reclamation and National Park Service projects adjacent to, inside, or outside of national forest boundaries when those areas affected a common reservoir. The agreement, between two agencies with different missions, has required constant negotiation, particularly in the Southwestern Region, where so much National Park System land is within or adjacent to National Forest System boundaries. Recreation planning by one agency affects the other agency. The Grand Canyon, administered by the National Park Service, and one of the most popular scenic vistas in the United States, cuts through the Kaibab National Forest, which catches the spillover of visitors without participating in the appropriations or sometimes the planning for Grand Canyon developments. [45]

The Forest Service particularly benefited from the political and moral support of the National Forest Recreation Association, which was organized in 1948 and boasted most of its membership from the Western States, including Arizona and New Mexico. The association directed its efforts toward promoting the "greater use and enjoyment of the national forests." It sought to educate the public about "good manners in the forest," encouraged private campground and recreation development, and sought to help the Forest Service in such duties as providing campfire permits, fire protection, and clean-up and sanitation. At meetings in Pinecrest, CA, in 1955, and Tucson, AZ, in 1956, association members and Forest Service personnel discussed land-use fees, wilderness programs, resort entertainment, advertising, "good housekeeping," and winter sports. [46]

Winter Sports Blossom

Winter sports experienced an awakening in the 1920's, became something of an attractive novelty in the 1930's, and, in the 1960's and 1970's, blossomed into one of the most intensive recreational activities in the Southwest, generally at higher elevations—which happened to accord with national forest boundaries. Most of the developed ski areas in the Southwest are in or adjacent to national forests: Sandia Peak, Cibola National Forest; Sierra Blanca and Ski Cloudcroft, Lincoln National Forest; Santa Fe Ski Basin, Santa Fe National Forest; Sipapu, Red River, and Taos Ski Valley, Carson National Forest—all in New Mexico; Mt. Lemmon, Coronado National Forest; Fairfield Snow Bowl, Coconino National Forest; and Bill Williams Mountain, Kaibab National Forestall in Arizona. [47] In addition to the ski areas, the Forest Service identifies many "snow-play" areas as places where tubing, sledding, tobogganing, and other such activities commonly occur.

Winter sports have been an important addition to the recreational uses of the national forests, in part because they attract a different clientele, in a different season, thus affording year-round use to far larger numbers of the public than could otherwise be accommodated. Moreover, winter sports seemed to offer less threat to the natural environment. Although there had been some interest in skiing in the 1920's, not until improved roads were built, largely through CCC efforts, did real winter sports and ski activities develop.

By the close of the decade of the 1930's, "ski fever" was becoming a new phenomenon. In the Carson National Forest, 23 El Rito sportsmen took to the "runners" on Christmas Day in 1938. Every Saturday and Sunday thereafter that winter, skiers and fans on toboggans and sleds tried their skills in the Vallecitos Ranger District. An El Rito merchant offered "desirable" prices on skiing outfits, and it was clear that "when the snow and a merchant cooperate in the ski business, the people will benefit likewise." [48] This 1939 observation is in retrospect a serious understatement of the realities of the modern commercial winter sports and recreation industry. But it was an accurate premonition of things to come.

In January 1940, El Rito residents organized the El Rito Ski Club. The Taos Winter Sports Club and the Amarillo Ski Club bought a new ski tow cable for the Agua Piedra ski course that year. Stories about skiing at Agua Piedra appeared in two national sports publications. In March, ski enthusiasts assisted in the rescue of stranded motorists near Holman Pass. Four hundred and six people registered in the Agua Piedra ski shelter during the 1940 season, and forest officials estimated that they represented only 10 percent of the total people who used the shelter. Thus some 4,000 skiers tried the slopes at Agua Piedra that winter; most of the out-of-state visitors were from Texas. [49] The growing public enthusiasm for winter sports prompted the Southwestern Region to conduct an official inspection of winter sports.

Robert S. Monahan of the Forest Service completed a study in 1941 and concluded that once the public (and especially the population of western Texas) became aware of the ideal snow and skiing conditions in the mountains of New Mexico and Arizona, investments in such areas would be more than justified. Monahan believed that the Agua Piedra area near El Rito and the La Madera area offered the best opportunities for expansion. The Arizona Snow Bowl, being developed by Flagstaff ski enthusiasts with the warm support of such Forest Service personnel as Edward C. Groesbeck in the Coconino, was ideally located, but access roads were then very primitive. The Hyde State Park ski area near Santa Fe was small and very limited in its snow season. Monahan believed a ski area on national forest land near Santa Fe should be considered necessary. A ski area near Big Tesuque offered possibilities, as did one at McGaffey near Gallup, NM. Roads and access were something of a problem in every winter sports area. Monahan believed that winter recreation developments complemented summer recreation programs. He advised giving priority to developing winter recreation areas near population centers, such as Albuquerque, Santa Fe, Las Vegas, Gallup, and Taos in New Mexico; and Prescott, Williams, and Flagstaff in Arizona. Cloudcroft was being developed as a private ski resort near Alamogordo in the Lincoln National Forest. [50]

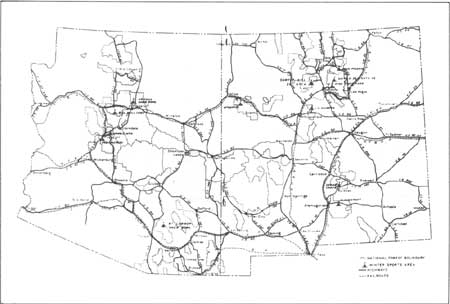

|

| Figure 50.—Winter sports areas in the Southwestern Region. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Monahan noted that permanent, heated log latrines were to be built at the Arizona Snow Bowl, La Madera, and Agua Piedra and were urgently needed. A comfortable, glass-fronted warming shelter built by private interests in Hyde State Park could be used as an example for future construction in ski area development. Rope or cable tows, as at McGaffey, Agua Piedra, La Madera, and the Arizona Snow Bowl, were operated by permit holders—usually local ski clubs. No charge was levied by the Forest Service for permits in several instances, while members of Flagstaff clubs at the Arizona Snow Bowl were charged $5.00 for a season until the lift costs had been liquidated. Monahan believed a $10 seasonal permit should be levied uniformly. [51]

Today's skiers would be intrigued and amused by the costs of a ski outing in 1941. The Agua Piedra lift near El Rito was a 900-foot rope tow that elevated the skier 225 feet above the starting point. An adult season ticket was $5, and a single-day ticket was 75 cents for adults and 35 cents for children. Dinner at a nearby private resort cost 75 cents. Hyde State Park used a 700-foot rope that elevated the skier 175 feet at a cost of 50 cents per day and 25 cents for children and ski club members. At La Madera in the Cibola, the rope tow was 2,000 feet long with an elevation of 300 feet, costing ski club members $5 for the season and nonmembers $1 per day. The Arizona Snow Bowl in the Coconino used a 1,750-foot rope tow that elevated the skier 340 feet, and a smaller portable rope tow was used for variable distances at a cost of 5 cents per trip. Hamburgers could be bought for 15 cents at La Madera and 10 cents at the Arizona Snow Bow1. [52]

The Hyde State Park area comprised 350 acres surrounded by the Santa Fe National Forest. The park was developed by the CCC under National Park Service supervision in 1935 and 1939 and was operated by the Santa Fe Winter Sports Club, which boasted 300 members who each paid annual dues of $2. The club paid $1 for its permit to operate and maintain the area and provided a ski instructor (Graeme McGowan), liability insurance, a warming shelter, a lunch concession, and a two-stage tow. Monahan thought the Hyde Park arrangements should be a model for future development. [53]

The report specifically identified Forest Supervisor Merker, Assistant Supervisor Charles, Staff Assistant Groesbeck, and District Rangers Keeney, Hodgkin, Zane Smith, and Sims as persons actively interested in and promoting winter sports. Monahan also commented that "the difference between a Forest Service Officer dressed in winter uniform and able to ski and one who doesn't ski and has no winter outfit" is striking. [54] In the latter case, the public gets a very unfavorable view of the Forest Service, he said, and he advised that:

the growing, public interest in winter sports, many of which can be found in large measure only on National Forest land in the Southwest, affords a remarkable opportunity to guide this enthusiasm as a vehicle for explaining other land use activities. Included in the membership of the various ski clubs are many present and potential community and state leaders whose support is of growing value. [55]

Monahan advised good public relations efforts, publicity, informational programs including press and radio reports on snow and weather conditions, and "positive" roadside signs. For example, he advised that instead of the "No Smoking," "No Tree Cutting," "No Fireworks" signs, there should be roadside notices that advise the traveler on "Rules for National Forest Winter Sports Area," "Good Skiing Ahead," and so forth. [56] As with other developing recreation activities in the late 1930's, winter sports expansion was aborted by World War II, and until the mid-1950's, there was little opportunity or effort to catch up.

By the winter of 1954-55, winter sports developments had not changed markedly from the rather informal, noncommercial, club-oriented pattern set before World War II. The Southwestern Region published a brochure entitled "Winter Sporting in Your National Forests" that winter, which advised that "all winter sports areas in the National Forests are public and free," but that where tows had been erected under permit by a ski group, the operators were allowed to charge a small fee for its use.

The 1954 brochure identified five winter sports areas in Arizona: the Arizona Snow Bowl, Bill Williams in the Kaibab, Mingus Mountain and Indian Creek in the Prescott, and the Mt. Lemmon Snow Bowl in the Coronado. It listed eight in New Mexico: adding to the older Agua Piedra (Carson), Hyde State Park (Santa Fe), La Madera and McGaffey (Cibola), and Cloudcroft (on private land in the Lincoln) two new areas in the Santa Fe National Forest (Sierra de Santa Fe and Sawyer Hill) and Cedar Creek in the Lincoln National Forest near Ruidoso. [57]

|

| Figure 51.—Sierra Blanca Ski Area, Lincoln National Forest, operated by the Mescalero Apache tribe. |

Development of Ski Areas

The development of the individual ski area is perhaps exemplified by La Madera (Sandia Peak). In the 1920's and 1930's, hearty winter sports devotees, many of them from the Northeast and Midwest, engaged in winter play and some skiing on the higher slopes of the Sandia Mountains. These slopes were made accessible by the automobile and road building; considerable road construction occurred in the early 1930's under Forest Service auspices and with CCC labor. By the late 1930's, sufficient interest in winter sports led to the organization of the Albuquerque Ski Club. The club obtained a special use permit from the Forest Service to operate a rope tow and a restaurant. The club operated the lifts from 1937 until 1946, when Robert J. Nordhaus organized the La Madera Company and assumed operations under a Forest Service Permit (with the blessings of the Albuquerque Ski Club) until 1963. In 1963, Nordhaus organized the Sandia Peak and Aerial Transway Company to raise more capital. The Sandia Peak company built a chairlift on the east side to the top of the mountain and a long tramway system on the west side extending from the base to the Summit House Restaurant and it has since continued to operate a modern ski area. [58]

Like Sandia Peak, modern ski facilities using staged chairlifts as opposed to the older rope tows, with resident lodges, restaurants, snowmobiles, saunas, spas, and hot tubs, date from the mid-1950's, with most of the construction and heavy capital investment occurring since 1965. Most of the current ski capacity has been developed since 1955. In New Mexico, use by skiers rose 30 percent between 1955 and 1964, and it has continued to climb. Cross-country skiing began to rival or exceed downhill skiing in popularity. Snowmobiling became significant in the mid-1960's. By the end of the 1960's, the Forest Service was estimating that $350 million in new recreation facilities would be required for the next decade. [59]

A Surge of New Visitors

President Lyndon Johnson urged "strengthening the cooperative relationship between government and private enterprise in the field of outdoor recreation." [60] Both government and private recreation industries struggled to raise the capital to meet the surge of new visitors to the national forests and winter sports areas. The Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965 allowed for increased fee charges and created the Golden Eagle passport system for year-round admission to Federal fee areas. The Golden Eagle "all areas" passport was discontinued and replaced by a local fee system after 1968. Although receipts averaged $100 million during the first 5 years, the fee system brought new problems. [61] People like Nordhaus argued that new fee formulas discouraged private capital investment. And, those who paid fees seemed to expect more from the Forest Service than in the past, including greater personal security, cleaner campgrounds, more modern facilities, and other amenities. In addition, there seemed to be some evidence that fees collected tended to be spent on campgrounds, recreation areas, and historic places in the Eastern United States rather than in the Western States. Privately owned, developed recreation facilities, within and on the margins of the Southwestern Region forests, began to supplement and replace those built and operated by the Forest Service. The Forest Service, in turn, began to move toward the idea of maintaining and preserving the setting for outdoor recreation, as opposed to the facilities.

The Forest Service began to prepare feasibility plans for the development of new ski areas under permits to private industry. Areas under consideration included the Sangre de Cristo in the Carson National Forest, 6 miles above the Red River; Gold Hill in the Carson; Mount Taylor in the Cibola; Elbe Mountain in the Santa Fe Forest; and Las Huertas in the Cibola near Albuquerque. Expansion and the acceptance of bids for permits were in each case to be contingent upon new access roads, although Sangre de Cristo and Gold Hill were both considered accessible. Projections were to open all of the areas between 1969 and 1973. [62]

Nine Major Ski Areas

The Vietnam War, energy crises, and new expansion by existing ski areas, which absorbed the projected increase in visitors, resulted in the Southwestern Region having nine major ski areas and six designated snow-play areas. The Southwestern Region recorded 17,475 people at one time in ski areas and 1,565 in snow-play areas in 1983. [63] Major ski and resort expansion in Colorado, Utah, Nevada, California, and Canada in the 1970's and 1980's have slowed further winter sports expansion in the Southwest. Nevertheless, winter sports and the traditional camping, fishing, hunting, and other recreational activities have generally replaced grazing, timber harvests, and mining as the single most important source of private regional income. [64]

In addition to the expansion of winter sports in the 1960's and 1970's, major developments occurring under the stimulus of Federal legislation affected recreation in the National Forest System as well as forest management. The passage of the Organic Act of the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, under the authority of the Department of the Interior in 1963 (P.L. 88 629), established inventory and classification systems for all Federal agencies related to recreational areas or activities. The Bureau was authorized to develop a nationwide outdoor recreation plan, gather and classify recreational data, prepare an outdoor recreation manual, and generally provide a framework for Federal, regional, State, local, and private recreation programs. [65]

The Wilderness Act

Wilderness, a concept long cherished by forestry personnel and the public in the Southwest, became a policy under the Wilderness Preservation Act of 1964. The act defined wilderness as an area "where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain," or areas where "the imprint of man's work [is] substantially unnoticeable." The act required the maintenance of wilderness areas and the exclusion of most activities except grazing cattle, mining minerals, and building trails. Timber cutting was generally precluded. After 1985, mineral prospecting was prohibited in wilderness areas. Hikers and campers were instructed by foresters to leave no trace in wilderness areas. [66]

The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968 placed similar protection on designated areas, such as the Rio Grande of northern New Mexico. The National Trails Act of the same year encouraged and provided some funding for a system of recreational and scenic trails, and the National Environmental Policy Act required an environmental impact study and formal public review of all proposed government actions affecting the natural environment. This act prompted the Forest Service's Roadless Area Review and Evaluation (RARE I) of all roadless areas of more than 5,000 acres for possible wilderness designation. RARE I evaluations, conducted between August 1971 and June 1972, designated some areas for wilderness study and others for multiple-use management, but any action was halted by court litigation instituted by the Sierra Club. The result was that all projected multiple-use management areas would require an environmental impact statement. [67]

New Wilderness Areas

RARE II studies, completed in 1979, led to the New Mexico Wilderness Act of 1980 and the Arizona Wilderness Act of 1984. The New Mexico act created nine new wilderness areas and added 223,357 acres to existing areas, totaling 606,502 acres of designated wilderness. The Arizona act created 30 new wilderness areas or additions to existing wilderness areas. [68] Those wilderness areas within the national forests of the Southwest are identified in table 15.

Table 15. National Forest areas in the National Wilderness Preservation System of the Southwest, 1984

| Forest | Wilderness | Acres |

|---|---|---|

| Arizona | ||

| Apache | Bear Wallow | 11,080 |

| Mt. Baldy | 7,079 | |

| Coconino | Fossil Springs | 11,500 |

| Kachina Peaks | 18,200 | |

| Munds Mountain | 18,150 | |

| Red Rock-Secret Mountain | 43,950 | |

| Strawberry Crater | 10,140 | |

| West Clear Creek | 13,600 | |

| Wet Beaver | 5700 | |

| Coconino/ Kaibab/ Prescott | Sycamore Canyon | 55,937 |

| Coronado | Chiricahua | 87,700 |

| Galiuro | 76,317 | |

| Miller Peak | 20,190 | |

| Mt. Wrightson | 25,260 | |

| Pajarito | 7,420 | |

| Pusch Ridge | 56,933 | |

| Rincon Mountain | 38,590 | |

| Santa Teresa | 26,780 | |

| Kaibab | Kanab Creek | 63,760 |

| Saddle Mountain | 40,600 | |

| Kaibab/ Coconino | Kendrick Mountain | 6,510 |

| Prescott | Apache Creek | 5,420 |

| Castle Creek | 26,030 | |

| Cedar Branch | 14,950 | |

| Granite Mountain | 9,800 | |

| Juniper Mesa | 7,600 | |

| Wookchute | 5,600 | |

| Prescott/Tonto | Pine Mountain | 20,061 |

| Tonto | Four Peaks | 53,500 |

| Hellsgate | 36,780 | |

| Mazatzal | 252,016 | |

| Salmone | 18,950 | |

| Salt River Canyon | 32,800 | |

| Sierra Ancha | 20,850 | |

| Superstition | 159,780 | |

| New Mexico | ||

| Carson | Cruces Basin | 18,000 |

| Latir Peak | 20,000 | |

| Wheeler Peak | 19,663 | |

| Cibola | Apache Kid | 44,650 |

| Manzano Mountain | 36,970 | |

| Sandia Mountain | 37,003 | |

| Withington | 19,663 | |

| Gila | Aldo Leopold | 202,016 |

| Blue Range | 29,304 | |

| Gila | 558,065 | |

| Lincoln | Capitan Mountain | 35,822 |

| White Mountain | 48,873 | |

| Santa Fe | Dome | 5,200 |

| San Pedro Parks | 41,132 | |

| Santa Fe/Carson | Chama River Canyon | 50,300 |

| Pecos | 223,333 | |

Generally, the wilderness areas are dedicated to preserving a part of the national heritage in its natural state. "Roads, motorized travel, logging, resorts, or other commercial developments are not allowed in wildernesses and primitive areas," and permits are often required for day or overnight access, usually for the protection of the visitor. [69] Wilderness programs have effectively altered the uses of almost 2,000,000 acres of land in the Southwest. Lumbering, commercial development, and mining have been most directly affected. Access in some instances is limited by the natural environment to the more serious and athletic outdoors person. The 1980 and 1984 New Mexico and Arizona Wilderness Acts have resolved recent years of public controversy, legislation, and litigation involving wilderness designations in the Southwestern Region.

The Wilderness designations have also complemented Forest Service initiatives toward dispersed recreation, thus encouraging the use of unimproved forest resources. In part because of increasing budgetary pressures, and in part because it historically has perceived the natural environment as a forest resource, the Forest Service has increasingly elected to leave "urbanized recreation" to the private sector. Hiking trails, bike trails, undeveloped campgrounds, and wilderness modify the natural setting as little as possible. This new emphasis represents a departure from the recreation policies between 1930 and 1960, which were concerned with accommodating (and controlling) visitors in developed camp and recreational areas. Budget cuts and new recreational policy attitudes, which actually harken back to earlier values, have combined in a few instances to eliminate landscape architect and other specialist positions. [70]

The idea and perception of recreation in the Southwestern Region have changed markedly since 1905, and certainly the reality of recreation has changed. Modern recreation in the Southwest is largely a phenomenon of the automobile. Previously inaccessible areas became increasingly available to domestic and out-of-state residents. The New Deal and the CCC enabled the Forest Service to accommodate urban visitors to the forests, but by the mid-1950's, old CCC facilities proved woefully inadequate. Massive public and private expansion of recreational facilities between 1955 and 1975 enabled the region to barely accommodate the onslaught of recreational visitors. But by the mid-1970's, the expansionist and fiscally liberal programs of the New Frontier and Great Society had begun to wane. Appropriations for recreational developments declined.

Tonto National Forest Becomes

Playground