|

Timeless Heritage: A History of the Forest Service in the Southwest |

|

Chapter 15.

The Life of Foresters

The life of the forest ranger in the Southwest has changed markedly since 1908, when the Southwestern Region came into being. The change has occurred on many levels. The background, work, and training of those who became foresters have changed; most especially, the lifestyles of the foresters and their families have changed. The essence of the change may have been captured by Charles Ames, who recalled the story of an old-time ranger, "worn out by the weight of years and too many reports," who, upon being berated by a supervisor for being unable to find a particular report in the overflowing office files, responded: "Spare your old ranger. It was the filing scheme, not me, that failed. Remember the many changes in the system rather than in me." [1]

The system has altered over the years but in the Southwestern Region, until recent decades, those changes have been largely imperceptible. There were times when the outside world seemed to bypass the Southwestern Region. Thus, in the 1930's, there were those in the Chief Forester's Office who considered the Southwestern Region the most backward region in the Forest Service. The region, its people, and its experiences, to be sure, were different; there has been a certain timelessness to the mission of the Forest Service in the Southwest, and a consistency and continuity in the character of the people who have served there. The mission is the same, but the way it is pursued has changed as have the people who seek to accomplish the work.

Over the years, the Forest Service brought in many different people from many parts of the United States to the Southwest, and most who came there stayed there. There are three major periods when the influx of new personnel affected the work and organization of the region. The first migration occurred roughly between 1908 and 1916 and can be loosely termed the frontier or pioneer phase. A small number of professionally trained foresters, mostly from the Eastern United States, directed the activities of a large contingent of untrained and largely uneducated forest guards and rangers, most of whom grew up in the West or Southwest. Many had no formal training but had passed the "ranger examinations," and some eventually became supervisors and staff personnel.

A second infusion of new blood into the region came during the Depression, when many young professional foresters left schools (often in the Midwest) and sought the only forestry jobs available with the U.S. government. Similarly, many staff and fire protection people came to work with the Forest Service during the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) days and remained for their working careers. Well into the post-World War II era, even into the 1960's, many Depression Era foresters and old-timers guided the activities of the region.

Finally, in the late 1950's, young well-trained college professionals, many of these specialists rather than traditional generalists, joined the Forest Service. In this more recent era, geneticists, paleontologists, hydrologists, range scientists, agronomists, chemists, engineers, archeologists, landscape architects, botanists and biologists, and public affairs specialists began to supplant and replace the traditional forester. The specialists tended to concentrate in the forest and regional offices and were available to serve the needs of the ranger district. The ranger increasingly became an office-bound administrator who directed the specialists to the particular need or crisis of the moment. In a real sense, the Forest Service became more urban, and more urbane.

Personal Sketches

In the following brief sketches, we glimpse the people who have been the harbingers of change and the guardians of a timeless heritage.

Edward Ancona, a graduate of Pennsylvania State University, arrived on the Prescott National Forest as a forest ranger in 1913. He had to learn about horses and cooking. Rangers in those days smelled of sweat and horses instead of grease and oil, or ink and air-conditioning, he recalls. Despite the changes Ancona witnessed during his long career with the Forest Service, he remembered the sense of timelessness:

The main thing about the Forest Service work was it put you into areas that you never would have been in any other job. You saw part of the past, a lot of the past, the early days; you could almost say the late-early days of the West. It was a terrific experience and I wouldn't have traded it for anything. It never made you a millionaire, but it was a darned nice life. [2]

Many of the early foresters in the Southwest did not just see the past—the old West—they lived it. Benton S. Rogers, for example, quit being a cowboy to join the Forest Service. He described the local ranchers in his district in 1914 as "hard hombres, carrying guns for each other." [3] Jesse I. Bushnell, who was born in Illinois in 1881 and arrived in Arizona when he was 26 years old, passed the ranger exam in 1909 and became assistant ranger on the Ash Fork District of the Coconino in 1910. Bushnell recalled the often violent conflicts between the cattlemen and the sheepmen, which lasted well into the 1920's. National Forest System lands were often trespassed by both sheepmen and cattlemen, thus bringing the Forest Service into the conflict. Happily, Bushnell finally succeeded in getting sheep and cattlemen to cooperate in widening the trail around Herder Mountain (an extension of the Heber-Reno Trail near Mesa, Arizona):

By George, they agreed to it and they'd been fightin' each other for years, gettin' out there with guns, and everything like that. The cattlemen agreed to have the trail widened out, and they widened it out, and there was never any more trespassing. [4]

|

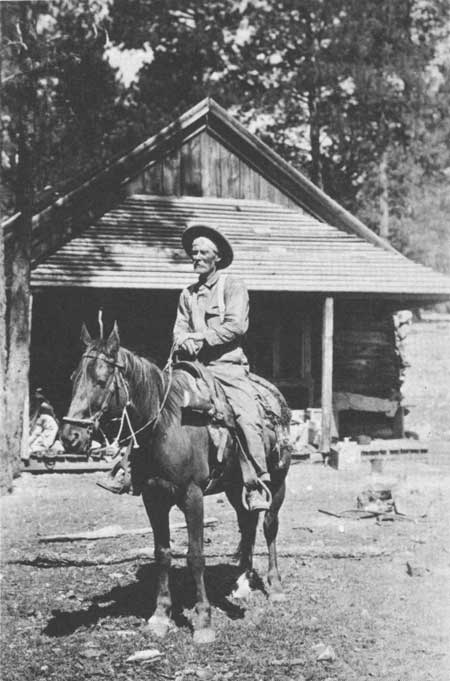

| Figure 52.—Forest assistant W.H.B. Kent on the Huachuca (now Coronado) National Forest, 1905. (Forest Service Collection, National Agricultural Library) |

Armed Ranger. Fred Croxon was one of a number of early rangers who went armed, although most chose not to do so. In 1921, Charlie Quail, of the "Quail outfit," began passing the word that he was going to kill Croxon. Finally, Croxon got a request to go to the Quail ranch to give permission to cut pinyon trees "so pastures would grow better." Croxon correctly took that as an invitation to a fight, and after agonizing for days and nights, decided he had no choice but to face his antagonist. Once he arrived on the ranch, Quail accused him of trespass and went for his .38 Savage automatic. Croxon drew his pistol from his belt, shot and missed, but killed Quail on the next two shots. The jury (and apparently the Quail family) acquitted him. [5]

Croxon began his Forest Service career as a result of one of those fortuitous meetings or encounters that so often influence one's life. In Nevada in the winter of 1907-8, he met a forest ranger from the Toiyabe National Forest, and on a "horse trip" in the Big Smoky Valley he met another, and in the summer two more from California. "All these forest rangers were fulfilling their duties on saddle animals and pack horse outfits. After meeting and talking with the men in regards to their duties, my desire to become a forest ranger was first in my thoughts." [6] Croxon qualified as a ranger and in 1911 received his first assignment—as fire lookout on Woody Mountain, 10 miles southwest of Flagstaff. He recalls that he was the first forest officer to be assigned permanent duty as a fire lookout during fire season in the Southwestern Region. His equipment was a Forest Service badge, compass, telescope, notebook, shovel, rake, and axe. He provided his own horse and bedroll. [7]

As had Croxon, Fred Merkle had a chance encounter with two forest rangers while hunting in the Sandia Mountains near Albuquerque in 1908. The rangers visited with him, talked to him about hunting and building fires, and rode on. Merkle recalled, "I decided at that time that was the life for me if I could get in." [8] He took the examination, became a forest guard in Oklahoma, arrived in the region in 1913, and ended his career in 1941 after 6 years as supervisor of the Sitgreaves National Forest.

Jesse Nelson had worked as a bronco rider and ranch manager for Buffalo Bill before joining the Forest Service about 1910. After service in the Southwestern Region, Nelson became inspector of grazing in the Washington Office and also served as chief of grazing in the Rocky Mountain and Pacific Southwest Regions. Nelson remembers the frontier spirit of the Forest Service in the early days:

Those were the good old days and we'll never see anything like 'em again. It was a period of tremendous crusading spirit ... a lot of those fellows that had the crusading spirit didn't know anything about Forestry. They were ex-cowboys and lumberjacks and all that sort of thing... [9]

|

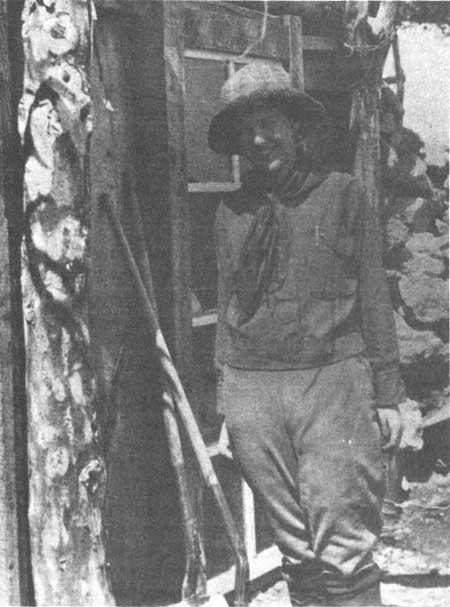

| Figure 53.—Forest assistant Clyde Leavitt (right) and packer Bill Donovan (left), on the Huachuca (now Coronado) National Forest, 1905. (Forest Service Collection, National Agricultural Library) |

Yale School Graduate. A 1914 graduate of Yale Forestry School, Stanley Wilson arrived on the Huachuca District of the Coronado in time to help round up 300 head of stolen Mexican cattle ranging on the national forest. Although the cattle were returned to the Mexican owners, no charges were brought against the prominent New Mexico rancher who had apparently bought the cattle from the rustlers. [10] Wilson became supervisor of the Carson National Forest in the 1920's and, like so many others, retired in the Southwest.

Frederic O. Knipe, who first tried cattle ranching in 1911, desired "more adventure" and joined the Forest Service in 1916. Knipe remembers that life with the Forest Service was not "altogether a soft, easy-going life, what with rough times, fighting fires, camping out in cold weather and sometimes the extreme opposite in long hard rides in hot weather." [11] It was an unregulated life with long hours, ". . . a rewarding experience, not glamorous but very worthwhile," he said. [12]

The rugged nature of the early rangers' life is partly testified to by a note in the Datil Tri-Monthly for May 31, 1911. Dallas F. Wells and Robert L. Deering were doing boundary survey work: "Mr. Deering has pushed this work under difficulties. His first horse dropped over a cliff; his next one went lame; the camp outfit burned up one day in the absence of himself and crew, and finally he was left stranded in the field by his teamster who complained that he was being worked too hard." [13]

Floye W. Carlton joined the Forest Service as a clerk in World War II. She and her husband spent most of their lives on the Blue River in the Apache National Forest. She gathered considerable information about the early history of Blue River. Even at the beginning of the 20th century, buffaloes, mountain lions, bears, deer, wolves, and coyotes roamed the countryside. The settlers were primarily cattle raisers who pooled their herds and men and boys in the annual roundups. Drought, overgrazing, and even floods (1906) made life hard. The Cospers (J.H.T. or "Uncle Toles" and John or "Uncle John") gave a dance once or twice a year at their Y-Y Ranch, which they had bought from the McKittricks. Guests would come and stay a week, and the Cospers provided food for horses and people, and entertainment. Dances began at sundown and lasted until sunup, and a barrel of moonshine or whiskey was ready at hand. Clay Hunter, she recalled, was the resident hunter who lived in a cave on the Upper Blue and lived on the bounties he received for wolves and bears. He got ten grey wolves and a bear on one trip and trapped seven mountain lions on another. His "hunting cave" was often visited by the outlaws who included Billy Johnson, the Smith Boys, and Sam Dill. [14]

|

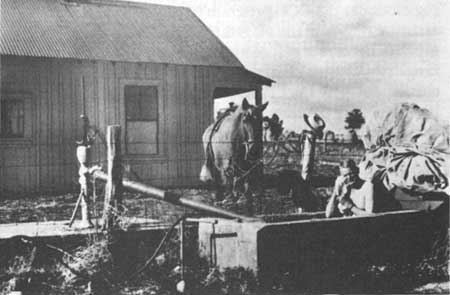

| Figure 54.—"Uncle" Jim Omens, famous mountain lion hunter on the North Kaibab Plateau, who killed many predators for the Forest Service. |

Renowned Hunter. One of the most renowned hunters of the Southwest, who inherited the skills of the earlier mountain men, was "Uncle" Jim Owens. Q. David Hansen, a retired forester from the Intermountain Region, saved some of Uncle Jim's stories, which had been written down by William M. Mace. Bill Mace began his Forest Service career as an assistant forest ranger on April 1, 1909, on the Kaibab National Forest. "During my younger days," Mace wrote, "it was my good luck to have several hunting trips with James T. Owens." Mace described Owens as then almost 60 years old, with hair and mustache slightly grey, standing 5 feet 8 or 9 inches, slight in build, but of tough and tireless strength. He had a quiet dignity and a personality that enabled him to be friends with all-ranging from Theodore Roosevelt to a Paiute Indian lad who rode for the Bar 2 Cattle Company. At the time, Owens served as game warden in the Grand Canyon National Game Reserve, which covered the same area as the Kaibab National Forest. He was born in 1849 near San Antonio, TX, and spent some time as cowman, buffalo hunter, and Indian fighter. [15]

Mace spent a month with Owens and a pack of hounds and pack horses hunting cougar on the north end of the Kaibab. On the rim of the Grand Canyon, they bagged three mountain lions after following them for hours where horses could not go. Owens's favorite hound, "Pot," later wore a silver collar with the inscription: "I Have Been at the Death of More Than 600 Cougars." Owens gave his dogs first consideration, his horses second, and himself third. Theodore Roosevelt had given Owens a silk tent after their successful 1913 hunt, and one story related by Dan Judd of Fredonia recalls that during a heavy rainstorm he came into Owens' camp and found him asleep in a tarpaulin under a pine tree, while the five hounds were "snugly quartered in the silk tent." Mace remembers Owens killing a coyote at 400 yards with the .30 caliber army rifle given him by Roosevelt. Owens died in Las Cruces, New Mexico, on May 11, 1936, after spending his declining years fighting to preserve bison and wild game in general. [16]

|

| Figure 55.—Forest assistant on the Apache National Forest. (Forest Service Collection, National Agricultural Library) |

Q. David Hansen recalls Kanab in the early 1920's: walking down Main Street, you passed the drug store, and about the only people you would see would be "the old-time cowboys sitting in the sun, boots and Bull Durham tags out their pockets, telling how they worked for Grand Canyon Cattle Company." [17] With an estimated deer population of 50,000 on the Kaibab, the Forest Service declared open season on deer in 1927 or 1928, he recalls. "Any hunter could get 3 bucks only for $5.00. But the deer were very poor and not edible. They had very unusual horns. They were considered trophies." [18] He recalls attempting deer counts. "We could stop on a ridge on those western slopes, riding through there and whistle and holler and hundreds of deer would file out of a canyon," he said. When the Forest Service declared open season, the State of Arizona filed an injunction and sent deputy sheriffs to arrest the hunters. Forest Service personnel helped the hunters dodge the sheriffs. Finally, a cooperative agreement was reached that allowed hunting only in October and November and required a payment of $4.00 for an Arizona hunting license. [19]

Hansen, who was assigned to work several of the special Kaibab deer camps, recalls the activities as follows:

Hunting camps were set up. Two on the east side of the Plateau, one at Kane Springs and one at South Canyon. Three camps on the west side, one at Ryan (checking station), one at Moquitch and one at Big Saddle. Big Saddle was against the rim of the Grand Canyon. A short walk from the camp was Crazy Jug Point, which was a spectacular view of the Grand Canyon. These hunts were very successful, being the first attempt at managing hunting. All hunters registered into a camp. A Forest Ranger and an Arizona Game Warden were in each camp. All the deer were checked out with a special tag. All guns were sealed when entering two checking stations, Ryan and Kane Springs, and unsealed at the Camps. This was a safety measure to keep hunters from shooting deer along the road. Horns were measured and carcass weighed and measured.

The Camps were under Special Use Permits to provide tents, meals, and horses to the hunters, if they so desired, also guides were available. So the hunters could drive in and have all the accommodations that they wanted, which was rather primitive, but satisfactory. In 1929, the hunters came, everything was very prosperous, good cars, and they enjoyed their stay in the Camps, even after bagging their deer.

The 1931 hunt was different because of the depression. A lot of hunters could see a difference in their pocket-books and they were anxious to get meat. After two years of controlled hunting, the deer were still not in good flesh, the average weight in bucks in 1931 was 135 lbs., the average weight 10 years later, was 180 lbs. By 1941 the forage had improved considerably. However, which is usually the case with winter loss, nature seems to solve the problem, along with hunting. [20]

Bertha Schell. Men were not the only hunters of renown in the Southwest. Bertha Schell worked for the Forest Service for 5 years in the 1930's on the Prescott at Camp Wood on Hyde Mountain. Her job was to pack supplies into the camp. Bertha was widely known as a hunter who tracked and bagged deer and lion. She remembered that the Forest Service never noticed her until she killed a mountain lion. "Then they came to chastise me." Her husband, Hardy, managed the Yolo Ranch. Bertha, for a time, leased and worked the Black Pearl Mine, south of the Yolo Ranch. When interviewed in the 1970's, Bertha remembered Ranger W.H. Koogler of the Walnut Creek District with fondness. "He was everywhere," she said. "Nothing went on in the forest that he didn't know about and the people liked him. He was a good cowboy." [21]

One of the stories that later circulated about Koogler is that when he and a revenue officer went into the forest to break up a moonshine operation, an "independent, hardheaded little burro" was the only living thing they found. The burro took off in a different direction loaded with two barrels of whiskey and later turned up at the Yolo bunkhouse. The ranch foreman fired all hands after they remained soused for a week. "Moonshine," the burro, became a folk hero, and soon the hands were rehired. [22]

Lafayette (Laf) S. Kartchner was born in Snowflake, AZ, in 1893 and completed high school in 1915. He took his ranger examination in October and was called into duty as a lookout on the Deer Spring Tower. Eleven days later, he was called up with the State militia and spent the next 3.5 months patrolling the Rio Grande. He then became an assistant ranger under Ranger James L. Hall at the Heber Station on the Sitgreaves National Forest and, within 2 months, was promoted to ranger and assigned to the Chevelon District. On the morning of March 28, 1917, he put his camp bed on the big roan mare, "Clip," said goodbye to the Halls, and went along the 4 or 5 miles north to the old Casby crossing in big Chevelon Canyon. The next day, the old ranger signed over the property, and following a "warm farewell," they never met again. Kartchner saw a trail going down into the canyon, put a rope on Clip with her little colt following, and "we all three learned where we had to go to get our water." [23]

|

| Figure 56.—Miss Anderson, lookout at Hillsboro Peak, Gila National Forest, 1923. (Forest Service Collection, National Agricultural Library) |

Kartchner decided, upon the advice of Ranger Dolf Slosser, to follow the fall roundup. So he took three horses, a tarpaulin, and several quilts and joined up with the Tom Dye ranch hands. "That turned out to be the best experience I could have had, learning my district and the people in it," he said. Kartchner soon was called into military service, and after service at Verdun, was discharged from Fort Bliss, TX, in 1919. He returned as ranger to the Heber District. He married, got the opportunity to move to the Show Low Ranger Station (which had running water), and, from 1925 until his retirement in 1956, spent much of his time managing timber sales from such places as Heber, Snowflake, Springerville, Williams, and Flagstaff, AZ. [24]

Had Army Service. Virgil D. Smith was raised in Ohio and spent two years at Marshall College in Huntington, WV, before enlisting in the Army in 1905. He was assigned to Troop F of the Fifth Cavalry in Wyoming, which had the dubious assignment of returning a group of Ute Indians, who were making their way to Canada, back to the reservation. The soldiers located the Indians and blocked off all routes of escape except the southern route, which led back to the reservation. After some discussion with the cavalry commander, the Indians elected to return to the reservation, which "relieved much tension."

After service in Colorado and Utah, Smith was sent to Fort Apache, AZ, where in 1908 he was discharged from the Army. Because of his skills in surveying and engineering, Smith received an appointment as forest ranger and was assigned the Heber District of the Sitgreaves National Forest, where his primary duty was to supervise the passing of sheep over the Heber Reno Sheep Trail in the spring and fall, as sheep passed from summer to winter range, and then back to summer ranges. He surveyed the boundaries of the trail, and attempted to keep the herds on the trail route. [25] Jesse Bushnell, mentioned earlier, was involved in settling cowman-sheepman disputes on the same trail in the Coconino in the 1920's.

After the sheep drives were complete, Smith was assigned to work on approving and surveying homesteading applications being processed under the Act of June 11, 1906, which allowed people to take up homesteads on the national forests. Smith remembered, "We carried our equipment on pack animals and would make metes and bounds surveys of the homestead areas applied for that were not on surveyed land, and then tie the survey to a known land mark, such as the forks of a stream or a Forest Service monument. . . ." [26]

In the 1920's, he was assigned duties as forest and range supervisor and, in 1930, was transferred to the Papago Indian Reservation at Sells, AZ, where he conducted range surveys, planned and built stock tanks and wells, and encouraged the Indians to develop their cattle herds while eradicating their wild horse herds. In 1933, he was given a similar assignment on the Navajo Reservation with headquarters in Ft. Defiance. Smith's surveys indicated severe overgrazing, and when he advised the Indians to get rid of "unnecessary" goats while maintaining their more productive sheep herds, the Indians dubbed him "Old Goat Hater." He was made supervisor of forest and range management for the Hualapai, Havasupai, Yavapai, and Verde Reservations in Arizona and the Moapi Reservation in Nevada, with headquarters in Peach Springs, AZ. He retired after a term with the Indian Service in the Department of the Interior on January 1, 1950. [27]

Colorful Career. Gilbert S. Sykes was born in Flagstaff and grew up in Tucson, where his father, Godfrey Sykes, was a staff member of the Carnegie Desert Laboratory, which later became the Santa Rita Experimental Range administered by the Forest Service. In 1911, Gilbert and his brother Clinton were sent to school in England. The outbreak of World War I prevented their returning home. Gilbert joined the British Navy and served as a wireless (radio) operator under the tutelage of Marconi, who invented the radio. In 1919, he joined the Forest Service as a lookout in the Catalinas and assisted in establishing a heliograph (signal communications) system using army surplus heliographs. By the late 1920's, radio replaced the heliograph being used in remote areas. Sykes apparently had an unsatisfied yearning for adventure, for he left the Forest Service in 1924 to become a barnstorming pilot, a parachute jumper, and an aerial acrobat. When the barnstorming days ended in 1933 for Sykes, he returned to the region and spent the rest of his career on the Coronado National Forest—the last 23 years in the Nogales District where he retired in 1962. [28]

Forest rangers of the Southwestern Region were stamped from different molds, but all seemed to share a sense of adventure and a preference for the rugged, outdoor life. For example, Roger D. Morris, a trained forester from the University of Iowa, joined the Forest Service in Minnesota before World War I, then joined the Army and spent 20 months with the American Expeditionary Force in France before returning to forestry duties in Minnesota. In 1920, he transferred to the Southwestern Region to participate in a range reconnaissance effort that lasted 6 years, most of those years in the field living out of tents and hauling supplies and equipment on pack horses. He headed the range reconnaissance during the last 2 years. He covered, on foot, the Santa Fe Forest in its entirety and the New Mexico portion of the Apache. Morris recalls one of those rare occasions when he savored the comforts of civilization. Having left a truck with a broken axle at the top of a mountain pass, Morris and his crew chief borrowed a team of horses and hauled the truck down into El Rito. He spent Thanksgiving Day at the only hotel in town and was served venison, mallard duck, bear steaks, and wild turkey for his dinner. Morris retired as assistant supervisor in charge of fire control and timber management of the Coronado National Forest in 1957. [29] Unlike the more contemporary forest ranger, early rangers were, by preference and by necessity, woodsmen.

Familiar With Forest Users. The Southwestern Region policy encouraged close familiarity with and knowledge of the forests and forest users. As Stanley F. Wilson explained, "In my day of course we rode horseback. We were encouraged to make trips where we had nothing in particular to do except see the country. I never made a trip of that sort but what I came up with was something I ought to know." [30] Instructions for early foresters were often quite simple—patrol as much country as possible and keep down fires. Henry Woodrow, who began as a forest guard in 1909, passed the ranger exam in 1910, and retired in 1942, began his work with chuck (food), one horse, and a bedroll that he supplied himself. "No tools were furnished me. I took my axe and shovel—all the equipment I had with which to fight fires. No tent was furnished, had an extra tarp which I used for a tent when it rained." [31]

As a ranger on the McKenna Park District of the Gila, Woodrow discovered he had inherited a particularly difficult situation with a widow who had a grazing permit on forest lands. As he told the story shortly after his retirement:

There happened to be a widow on this part of the District with a grazing permit on the Forest and a ranch near the Gila Station. So I married her on October 14, 1912. Later I heard of Rangers on other Forests and Districts having quite a bit of trouble with widow permitters in the District. I would suggest that the Forest put a single man for a Ranger there and probably he would marry her and stop all of the trouble. [32]

There is certainly no evidence that such careful planning ever became a part of Forest Service policy, but there is ample evidence that widows as well as eligible young ladies frequently married rangers.

The advent of the automobile began to change the lifestyle of forest rangers, but the changes were at first little noticed. The automobile made it possible for the ranger to cover more territory and to complete much of his work more efficiently. A ranger and his family could live in "town" and drive to the woods. It also began to affect the woodsmanship or "woods-sense" of the forester. Technical knowledge clearly became more important. Personal knowledge of the woodlands and even of neighboring people became less. Although the 1920's and 1930's marked the transition into a new era in the life of the Forest Service in the Southwestern Region, it was not nearly so apparent as might have been assumed. Even in the 1930's, the automobile and truck were not always central to the ranger's duties. Moreover, the real lifestyle of the ranger did not change rapidly or appreciably until after World War II.

Robert Diggs, a graduate of the Yale School of Forestry, arrived at the High Rolls CCC camp in 1933 as camp foreman. He was sent to the Jicarilla District of the Carson in 1935, which he described as "still a horseback district." While in the Jewett District, working under Bob Stewart, he met and married his wife Odie. Stewart allowed the couple one day and night away before returning to work Diggs remembers that the 1930's were the days when the work force on a ranger district meant "the Ranger and his wife." [33]

Samuel R. Servis from upstate New York was a graduate of the New York College of Forestry and, like Diggs, began his Forest Service career with a CCC job. Servis recalls his lifestyle in the 1930's as not unlike that of "old-time" foresters. He joined a roundup with "Old Cole Railston" of the V-Cross-T Ranch on the Cibola. He said they got up at 3 a.m., fixed a quick breakfast, rode like crazy until 3 p.m., ate biscuits, played "coon-can" until night, slept until 3 a.m., and then rode like fools until 3 p.m. [34]

Garvin Smith. Zane G. Smith, who spent most of his life in the Southwestern Region, remembers that his father, H. Garvin Smith, joined the Forest Service in 1917, when Zane was 8 years old. After a few months experience in the Capitan District of the Lincoln National Forest, he was transferred to Mayhill District as ranger. Smith said that his father "was a high school graduate and had experience in farming, ranching, and biological survey. He was representative of the rangers until the 1930's, when there was an influx of forestry graduates with the CCC programs." [35] In the Mayhill District, boundaries were poorly marked, and livestock trespass and overgrazing were everywhere. Stockmen, he said, who largely dominated State politics, resented Forest Service controls, and corrective actions were therefore difficult to achieve. Renewing homestead applications took up a sizable part of the workload—not to mention fire control and timber management. [36]

The family moved to the Cloudcroft District of the Lincoln, and then to the Chloride District of the Datil National Forest in 1923. The family moved on horseback with a few pack animals, and household goods were shipped by rail from Alamogordo to Magdalena and by wagon to the Chloride Station. Communications through the 1920's was by grounded party telephone lines, and most stations were located far from towns. Rangers' wives usually served as dispatchers and received a $5 per month stipend during fire season. Zane Smith began his work as a fire lookout on the Gila in 1926 and, after completing college in 1931, served as ranger and on the supervisor's staff and regional office staff for 33 years; for 5 additional years (1952 to 1957), he served as forest supervisor in the Northern Region and on the Chief's staff. [37]

Although wild animals were ordinarily no threat to humans who were reasonably circumspect, and the population of cougar and bear had declined considerably by the 1930's, nevertheless, there were dangerous creatures in the woods. In 1931, ranger O.J. Olson was allotted $300 by Supervisor. Fred Winn to build a telephone line from Sunnyside on the west side of the Huachuca Mountains to Miller Peak Lookout, a distance of 6 or 7 miles. Olson recalls that he hired two young men, Norman Johnson and Abraham Ruiz, to build the line. He drove them to the starting point with bedrolls and gear:

Since it was late when we arrived, I decided to stay the night. We fixed a cold meal out of the chuck box. Then the boys spread their bedroll on the ground. The 3 of us got into bed with me in the middle. It was a beautiful night in August with a full moon lighting up the vast area surrounding us. About midnight I awoke with a bloodcurdling scream that sent both of my bedfellows scampering in different directions down the mountain side. I then realized I had grabbed for my nose and had a skunk by the throat. I squeezed until I thought he was dead, but to be sure, banged his head on a rock never letting his hind feet touch the ground to avoid being sprayed. [38]

The skunk was rabid. Olson began the Pasteur treatment, one shot a day in the arms, legs, torso, or buttocks, each swelling to the size of a small hen's egg. It was an extremely painful and grim ordeal and made him something of a sensation and a curiosity among local folks. Many curious callers over the next few years expected to see him turn up foaming at the mouth and wondered how his family stayed in the same house with him. The skunks, however, had not finished. The line crew, Johnson and Ruiz, while camped at an old mine shack, awoke in the middle of the night to find a rabid skunk fastened to the neck of their mule. Finally, after 7 years, doctors gave Olson a clean bill of health-and his family and friends were much relieved. [39]

|

| Figure 57.—Ranger Cleo J. Anderson, Jicarilla Ranger Station, Carson National Forest, 1963. |

Primitive Living Conditions. The rather primitive conditions under which the forest rangers and their families lived had not changed markedly by the end of World War II. Walter Graves moved his family from the Coyote Ranger District of the Santa Fe National Forest to the Long Valley Ranger District of the Coconino in March 1944. Graves was born in Chicago, completed his forestry training at Iowa State University, and took his first job as a CCC camp foreman at Hyde Park on the Santa Fe. He headed the Coyote District for 5 years before being moved to the Coconino.

The move was made in Forest Service stake-bed trucks. As soon as the family arrived at the Clear Creek Station, one of his children used the toilet, which promptly flooded the bedroom when it was flushed. The wood-burning stove had never been cleaned, and the grime had to be chipped away with a chisel. Cupboards were caked with jam, syrup, and dried foods. The two-bedroom house was too small and infested with termites. Scorpions, centipedes 6 to 8 inches long, and black widow spiders occupied the house, while outside rattlesnakes, porcupines, and "various other varmints ... would keep us awake nights with their yowling, fighting, and lovemaking." In 1945, the family was delighted to be moved to the Capitan Ranger District in the Lincoln National Forest. [40]

Other foresters who joined the region in the 1930's and whose careers in many ways paralleled or intersected with Graves included Dick Johnson, who was from Las Vegas, NM. Johnson began work in February 1937 conducting range surveys on the Tonto National Forest with Hollis Palmer as chief of the party. Dean Cutler, from Iowa, joined the Southwestern Region as a CCC foreman at the Woodsprings camp in charge of porcupine control. In 1935, he went to work under Fred Merkle in timber sales and stayed in the region until his retirement in 1973, but for an interlude in the Chief's Office in Washington, DC. Robert Courtney was born in a log cabin in northern California and completed forestry studies at Oregon State University in 1933. The only jobs available were with the Federal government, so he took a job as camp foreman at the Los Burros CCC camp on the Sitgreaves National Forest in Arizona, with a salary of $1,600 per year. He still remembers riding up to the camp on a truck carrying explosives. Courtney retired in 1970. [41]

Raised on Cattle Ranch. Stanton Wallace, whose father had been a forest ranger on the Coconino from 1904 to 1910, was raised on an Arizona cattle ranch. He graduated from Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff in 1932 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in education. He taught school, worked as a fire lookout, built telephone lines, drove teams, and went back to school to do graduate work in forestry and range management. He was hired by the region under the CCC program in July 1935 and was made assistant ranger in the Flagstaff District in August. He spent much of his career before his retirement in 1969 working on range surveys, grazing, and range management. [42] Very clearly, the New Deal programs, and the CCC in particular, brought many potentially unemployed forestry professionals into Forest Service employment. The result was an infusion of trained professionals, unusually well-qualified and ambitious young men, into the Forest Service at a particularly critical juncture of Forest Service development in the Southwestern Region and elsewhere throughout the United States.

As had so many others, Cleo J. Anderson worked in the region under CCC auspices during the Depression, but he went directly from the CCC into military service without having been a regular Forest Service employee. After World War II, Anderson experienced some difficulty in being reinstated under Civil Service and with the Forest Service. He finally obtained his appointment and served as ranger in the Payson and Williams Districts of the Tonto, in the Guadalupe on the Lincoln National Forest, and at the Jicarilla Ranger District of the Carson National Forest, among other duties. Lacking a college degree, Anderson thought himself lucky to have headed six different ranger districts during his career. His years, however, were not easy, and he developed considerable animosity for some of his colleagues and superiors. By the time he retired, after 33 years in the Southwestern Region, he became convinced that the Forest Service had become an "out-of-control bureaucracy" and that there had been many mistakes made particularly concerning summer home permits, grazing permits, and promotions. Many rangers' dwellings, he felt, had become grossly inadequate, if not dangerous. [43] Since his retirement, Anderson has compiled rosters of the rangers from the 60 or so ranger districts in the region. These are to be placed in a museum for the permanent record.

Although Anderson's concerns tended to be very specific and highly personalized, his premonitions that began to develop in the 1950's and 1960's had some basis. The region in 1950 was very much like it had been in 1935. The people were often the same, the houses were the same, and the work was being carried on in much the same way. But problems were clearly developing. Postwar inflation was affecting the whole Nation, but government pay seemed to remain critically low. Attractive employment alternatives with government, the military, and particularly private industry made recruiting and employment in the Forest Service difficult, even when rare budget increments made it possible to hire new personnel.

Pressures Increase. Pressures on personnel and staff also became greater, rather than less. Traditional permit activities such as timber harvesting, grazing, and building summer homes continued, while recreation, tourism, and other special uses soared. Moreover, rising conservation and wilderness preservation interests among the public increased the focus of public attention and the media on the Forest Service. Old-time foresters, unused to the necessity of the new "impersonal" public contact, the increasing bureaucracy, and mounting paperwork, chafed at the growing amount of white-collar desk and clerical work. In reality, the deluge of new conservation, preservation, safety, and open-hearings laws that made the work of the forester predominantly one of filing reports, answering charges, and appearing in court and public hearings was yet to come. By the mid-1950's, the urgency of reform and improvements finally began to be reflected in larger congressional appropriations to the Forest Service. Smokey Bear and the forest ranger's traditional image as a conscientious public servant, and a person who helped safeguard the Nation's forest resources, helped direct new funds into national forest programs in the late 1950's and throughout the 1960's.

This period marked the day of the new Forest Service professional and specialist. Special staff positions supplemented the forester's work at the ranger district, forest supervisor, and regional forester levels. Recreation specialists, archeologists, landscape architects, biologists, engineers, and other specialists joined the Forest Service staff in the region. Long-time foresters, such as Donald Bolander and Milo Jean Hassell, are very sensitive to the changes occurring in the work and personnel of the region since the 1950's.

Donald Bolander, whose father, A.L. "Archie" Bolander, spent his entire career on the Carson National Forest, was literally born and reared in the Forest Service. Bolander, currently supervisor of the Prescott National Forest, believes that in its exuberance to preserve the land and timber resources, the Forest Service has sometimes overlooked the interests of the "little guy" and the local community. He feels that the service had relatively little "cultural awareness" and that the influx of new people, and the specialist, contributed to a growing gulf between the residents and the users of the forest resources and the Forest Service. [44]

Bolander believes that the ranger, who was once a member of the community, has become a bureaucrat. Wives and children, who were once active members of the Forest Service "family," now live in urban centers and have little involvement with the service—and seem to prefer it that way. Moreover, those who work for the service have "8 to 5" jobs. Even if one desired to do so, working in excess of an 8 hour day is now prohibited by law, he said. He foresees a considerable decline in enthusiasm for a Forest Service career. There is too much bureaucracy, the people are different, the job is different, and there is too much paperwork. One can no longer really do a thing, he said. The outdoors is not even accessible to the professional forester. [45]

Jean Hassell Retires. Regional Forester Milo Jean Hassell announced his retirement from the Forest Service on July 2, 1985, after 31 years of Federal service. He was born in Chihuahua, Mexico, and reared in Grants, NM. He graduated from Utah State University and, while a student, worked in the summers on the Kaibab National Forest. He began his career as a junior forester in 1958 and became ranger on the Elgin District of the Coconino in 1960. With a degree in forestry, a minor in range management, and good experiences and associations with Hispanic and Indian groups in Arizona and New Mexico, Hassell had special concerns and competencies that uniquely fitted him for leadership positions in the region. Hassell believes, for example, that the Southwestern Region has tended to ignore the plight of the northern New Mexico villages whose economy and lifestyle had been so closely linked to grazing on National Forest System lands. And as Bolander had suggested, Hassell believes that regulations had tended to ignore the "little guy." [46] This sentiment was echoed by William Hurst, who preceded Jean Hassell as regional forester. Hurst explained:

... that it was not so much the attitude of the individual Forest Officers which encouraged neglect of local people and their needs as it was the policies of the Forest Service itself. For example, every citizen of the United States has the right to acquire a grazing permit on the National Forest through purchase with waiver of an established farm or ranch which has a grazing permit attached to it. Outsiders with money could and did come into the small, predominately Spanish speaking communities in Northern New Mexico, buy up the small farms and ranches and acquire the grazing permits. In a short time this left many local people without a traditional means of making a living since many did not choose to leave and seek employment elsewhere. Similar situations developed in the timber business where small sales were discouraged in place of large timber sales which local people were not able to handle. Because of these and other situations of encroachment, unrest fermented culminating in the Tijerina uprising of the 1960's.

To meet this challenge the Forest Service made major adjustments in its grazing and timber policies in Northern New Mexico and initiated a concerted effort to recognize the traditional needs of the local people. Rangers and staff officers were required to learn Spanish to improve communications. Contracting opportunities for fence, road, campground and other construction opportunities and work oriented projects such as timber thinning, among others, were made available to local residents. Grazing and timber policies were adopted making it more difficult for outsiders to acquire small timber sales and grazing permits in areas which had traditionally served local people. These changes, along with a strong emphasis on cultural awareness, was infused in the Region in the late 1960's and early 1970's. [47]

Hassell also believes that rangers, because of consolidation of the ranger districts and increasing paperwork loads, were losing contact with the land and the people. Specialization tended to widen the breach between the ranger's traditional role as one who was knowledgeable of the land and the people within his district. A ranger, he said, should know the land, and a ranger district must be a finite territory. He also was concerned that the Governor of Arizona had recently labeled the Forest Service as "30 years behind the times," because he felt it still thought of timber harvest as its major function—as opposed, for example, to the contemporary interest in and economics of recreation and tourism.

Hassell's career clearly aimed at keeping the region in step with the times. He had infused a new cultural awareness in the region. He believes that the Forest Service had, in fact, moved from the "axe and grounded telephone line" to the computer age. In making this rather difficult transition to the modern age, Hassell believes that the old dedication and pioneering spirit of Forest Service personnel lived on. [48] Jim Owens, Arthur Ringland, Bob Courtney, Ralph Crawford, Bill Hurst and so many before them had made an indelible imprint upon Jean Hassell, the region, and the national forests and its users. Times had changed, faces were new, people sometimes were different, jobs often were more technical, and paperwork was more ponderous, but the inherent mission and spirit of the Southwestern Region have survived.

Reference Notes

1. Charles R. Ames, "A History of the Forest Service," The Smoke Signal 16 (Fall 1967):123 (filed at the Coronado National Forest).

2. Edwin A. Tucker, "The Forest Service in the Southwest," manuscript, pp. 624-644, 641.

6. Fred W. Croxon, The Smoke Signal 16 (Fall 1967):127.

8. Tucker, "The Forest Service in the Southwest," pp. 617-624, 617.

9. Ibid., pp. 710-731, 730-731.

11. Frederic O. Knipe, The Smoke Signal 16 (Fall 1967):134.

13. Datil Tri-Monthly (newsletter), May 31, 1911, Magdalena, NM, Federal Records Center, Denver, 095-62A0296.

14. Letter from Floye W. Carlton to the author, April 1985.

15. Bill Mace, "Uncle Jim Owens, Master Cougar Killer of the Kaibab," unpublished manuscript in the possession of Q. David Hansen, Salt Lake City, UT.

17. Letter from Q. David Hansen, Salt Lake City, UT, July 5, 1985, to Henry C. Dethloff.

21. Virginia M. Brown, "Magnificent Land: A History of the Prescott National Forest," Prescott, AZ, July 30, 1976, unpublished manuscript in Prescott National Forest archives, pp. 38-39.

23. Letter from Lafayette C. Kartchner (age 91) to Henry C. Dethloff, May 16, 1985.

25. Virgil D. Smith, The Smoke Signal 16 (Fall 1967):139.

28. Ames, "A History of the Forest Service," pp. 125, 143.

29. Roger D. Morris, The Smoke Signal 16 (Fall 1967):137-138.

30. Tucker, "The Forest Service in the Southwest," pp. 662-700, 1699.

33. Ibid., pp. 1200-1213, 1205.

35. Letter from Zane G. Smith, San Diego, CA, August 1, 1985, to Henry C. Dethloff.

38. Memorandum from O.J. "Ole" Olson, El Paso, TX, August 5, 1985, to Henry C. Dethloff.

40. Letter from Walter L. Graves, Albuquerque, NM, August 1, 1985, to H.C. Dethloff.

41. Interview with Richard S. Johnson, Dean Cutler, and Robert Courtney, Albuquerque, NM, May 10, 1985.

42. Interview with Stanton Wallace, Albuquerque, NM, May 10, 1985.

43. Memoranda, letters, and clippings from Cleo J. Anderson, Cave Creek, AZ, sent August 5, 1985, to Henry C. Dethloff.

44. Interview with Don Bolander, Forest Supervisor, Prescott National Forest, Prescott, AZ, July 25, 1985.

46. Interview with Milo Jean Hassell, Regional Forester, Albuquerque, NM, May 10, 1985; News Bulletin, Southwest Region, Office of Information, July 2, 1985; Southwestern Region News (August 1985), p. 1.

47. Letter from William D. Hurst, Bosque Farms, NM, to Henry C. Dethloff, November 25, 1985.

48. Interview with Hassell, May 10, 1985.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

region3/history/chap15.htm

Last Updated: 22-Feb-2008