|

Timeless Heritage: A History of the Forest Service in the Southwest |

|

Chapter 17.

Management Improves the Land

Significantly, lands of the Forest Service in the Southwestern Region tend to be better because of the management. The region produces more timber today than ever before. Grasslands have been improved over their condition at the turn of the century. The Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands, part of the dust bowl not so long ago, now support over 11,000 head of privately owned livestock each year. The Clayton Livestock Research Center, operated by New Mexico State University, is located on the Kiowa National Grassland and conducts research on cattle diseases and grazing and feeding operations. [1] Once a major mining region, the Cibola National Forest now is a major recreation area, supports a rich wildlife population, and is the home for the Langmuir Laboratory for Atmospheric Research operated by the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology. The Laboratory specializes in studies of thunderstorm activity. [2] Water supplies have been substantially enhanced by the improvement of watersheds and the construction of reservoirs. Without the protection of the forests and improved watershed, the growth of the Sun Belt cities in the Southwest could not have taken place.

Wildlife species also have benefited from management. In the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest, conversion of a seasonal marsh into a 51-acre lake for disposal of secondarily treated sewage from the City of Show Low has improved waterfowl habitat. As a result, duck hatchings increased from 331 in 1980 to almost 3,000, and the new lake provides outdoor recreation opportunities for thousands of visitors. More recently, a dry lakebed in the Kaibab National Forest, called Coleman Lake, was flooded by blasting into underground reservoirs, creating several acres of open water, numerous channels, islands, and mounds for wildlife. Potholes have been blasted into the Cebolla Marsh on the Santa Fe National Forest to develop nesting islands. [3] Fishing habitats and opportunities have also been expanded.

Early in the present century, the Forest Service began a census of animal life in the national forests in order to formulate, in conjunction with the States, policies to protect and encourage wildlife. Wildlife biologists soon discovered that some species in Arizona and New Mexico had declined to alarmingly small and restricted populations and that others verged on extinction. Ranger Louis Cottam described conditions in northern New Mexico, commenting that "you could ride for hours and even days without seeing any large game, and bears and cougars were seldom reported." [4]

Protection of wildlife was somewhat of a problem to the Forest Service, because technically game animals were the property of the State and fell under the prerogative of its agencies. At the same time, however, the Forest Service was responsible to the Congress of the United States for administration and protection of the public forests. Fortunately, both the Forest Service and the States had intelligent and visionary leadership, and they usually have been able to work toward a common goal of conservation of the faunal resources. When controversy arose, as it did in Arizona over the Kaibab deer herd in 1924 and thereafter, compromises have been worked out. [5] The success of the Kaibab operation provided support for the wildlife biologists in the field, and evidence that the Forest Service and the State could cooperate for mutual advantage. [6]

In 1920, the Forest Service published the first comprehensive summary of big game animals in the national forests in the Southwestern Region. Wildlife biologists, who began to be assigned to the national forests in the 1960's, admit that game counts are at best approximate and that it is dangerous to compare individual years. However, as long-range indicators, the counts are highly accurate. [7] Once the basic conditions were understood, the States and Forest Service embarked on programs to protect the threatened species. Species under pressure were supported by hunting restrictions and habitat improvements, by scientific study of the species and their relationship to their habitats, and by reintroduction into habitats from which they had been eradicated. [8]

Many hunters and conservationists were shocked at the low population counts revealed in the 1920 big game report on the national forests. Although the report covered only game in the national forests, it was still considered to accurately reflect conditions in the Southwest as a whole, since the national forests furnished most of the available habitat. The fact that grizzly bears were almost extinct in the Southwestern Region or that black bears, cougars, wild sheep and goats, and javelina had declined to only a few hundred of each species was not alarming to many, but the revelation that the once-abundant elk and antelope numbered in the few thousands and that deer and turkey could be counted in the tens of thousands attracted considerable attention. Programs were launched immediately by both the States and the Forest Service to correct the situation. Some would take years to reach fruition; others began to reap dividends almost at once. [9]

A perusal of the wildlife reports from 1920 to the present gives an interesting and what has proven to be accurate picture of the game animals in the national forests. Elk are one of the better examples. All elk native to Arizona and New Mexico, the Merriam elk, became extinct about the turn of the century. Transplantation from herds began shortly after World War I. The elk population in 1920 for all of the forests in the Southwestern Region was on1y 585, and it increased slowly until today and has stabilized at 20,000, about the limit that the environment can support. Improvements have also occurred for many other species, including black bears and cougars. One of the more rewarding programs has been the wild sheep and goat program, which through careful management and the reintroduction into old habitat and new areas, has resulted in a constant increase from a few hundred to almost a thousand. [10]

Some efforts to maintain or restore wildlife populations have resulted in failure. The demise of the grizzly bear is an example. To be sure, cattlemen were pleased to see the grizzly removed because of its potential destructiveness to livestock. [11] The American antelope, on the other hand, had a strong and viable population by 1930, having responded remarkably to conservation measures. Populations rose three or four times in the 10-year period after 1920. Antelope remained stable for several decades at about 10,000 head, and then began a gradual decline in the 1960's, which continues into the present. Some wildlife personnel believe the open grasslands, which the antelope favor, are being invaded by brush and pinyon-juniper woods, restricting the available range and thus reducing herd size. [12] Judiciously applied prescription burning might well control such invasions of grasslands.

|

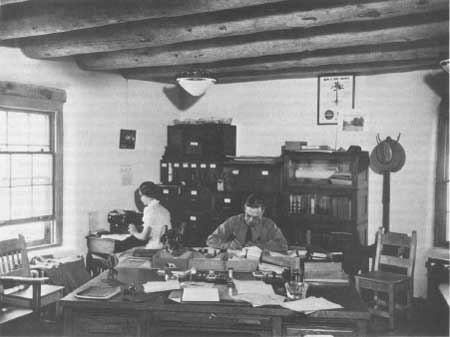

| Figure 59.—Forest ranger's office, Carson National Forest, Taos, New Mexico, 1939. |

Cooperation in Wildlife

The Southwestern Region has cooperated for many years with the Arizona and New Mexico Game and Fish Departments in improving fishing grounds and in more recent years in protecting threatened and endangered species. The Gila trout, Rio Grande cutthroat trout, Apache (Arizona) trout, and Gila topminnow are among the species that have received special attention. The Southern bald eagle, the peregrine falcon, and the Kaibab squirrel have been especially nurtured by the Forest Service.

The economic value of fish and wildlife resources in the Southwestern Region is estimated at approximately $135 million, with hunting and fishing accounting for $51 million, and the remainder being associated with viewing, photographing, and general enjoyment. The RUN WILD computer data base provides foresters and wildlife managers in the region with an unusually strong information base and is an important tool for environmental analysis projects. [13] Private and public agencies have joined the Forest Service in promoting the protection of wildlife and plant habitats.

In 1982, Pennzoil Corporation donated 100,000 acres of prime land in the Sangre de Cristo mountains to the Forest Service. The new lands were added to the Carson National Forest and are known as the Valle Vidal unit of this forest. The unit supports about 2,000 elk, 250 deer, 1,000 turkey, and many nongame animals. The wildlife on the Valle Vidal unit is administered jointly by the New Mexico Game and Fish Department and the Forest Service under a cooperative agreement authorized by the Sikes Act. Under this agreement, both agencies seek to provide both high-quality recreational opportunities and wildlife habitat protection. Similarly, the Sonora Desert Museum in Arizona has helped the Forest Service locate the endangered Rumex orthoneurus in new and more protected plant habitats. [14] Despite the great increases in the kinds and intensity of public use of the national forests, the wilderness and favorable plant and animal habitations have not only coexisted with people but have flourished.

Maps

An important work of the Forest Service that began in its first days on the job in the Southwestern Region has been to map and describe the national forests within the region. Although roads and trails may provide public access, maps explain where to go and what one might find along the way. Timber and range survey crews began the first serious business of map-making soon after the creation of the Forest Service. These crews marked roads, trails, buildings and prominent natural features on their working charts. [15] These early maps and charts have developed into a series of constantly updated, detailed maps that are available to both casual visitors and serious hikers. The maps are based on the U.S. Geological Service Quadrangles, and they contain pertinent information relating to the national forests and their management, and include information of general interest about the forest and the region. [16]

A quick perusal of the maps reveals useful and interesting information. Counties, towns, Indian reservations, other Federal lands, private lands, wilderness areas, and recreational facilities are identified. Highways, roads, and trails are located, and their condition described. A "primitive road," for example, means just that. Overall, the maps are accurate, attractive, easy to use, and moderately priced. They have become an essential factor in the management and use of the national forests.

These maps, as Charles F. Wilkinson commented, "hold out the secrets of the forest to tempt us all. There is magic," he said, "in the national forests":

You have all seen it, whether in the rump of a cougar heading over a ridge, in the sweep of a hawk on the wing; in the crumbling mass of a musky old-growth Douglas fir as it folds back, like us, into the soil from which it came; in the scratchy side of a sun-blasted canyon in the Arizona or New Mexico high country; or up at Pingree Park. [17]

Natives of the Southwest have long enjoyed the unusual scenic majesty of the region. At the turn of the century, writers, painters, and photographers caught the imagination of the American public through their descriptive works on the Southwest. Thomas Moran painted the Grand Canyon and other scenic attractions. Willa Cather popularized the area around Santa Fe National Forest in Death Comes for the Archbishop. Ansel Adams made Taos a household word through his photographs. Many an American's image of the Southwest was fired by Zane Grey's Under the Tonto Rim, among his other western novels, the setting for which is along the Mogollon Rim and areas of the Tonto, Coconino, and Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests. (Grey believed that Tonto had a better phonetic sound than Mogollon so he substituted the word Tonto.)

Under the National Forest Receipts Act of May 23, 1908, and the act of March 1, 1911, 25 percent of receipts from the national forests is paid to the State in which the forest is located for the benefit of schools and roads in the county in which the money is collected. As the flow of visitors began to increase, the Forest Service often contributed larger funds to the States. [18] County and State governments, in return, sometimes provide financial assistance in road building and park development. Road and trail expansion generally continued through the 1960's, but many miles of older trails and roads have been abandoned in more recent decades because of financial considerations and new emphasis on dispersed recreation and wilderness protection. [19]

Maintaining Trails

The Forest Service has recently inaugurated the "Adopt A-Trail" program, allowing interested organizations or groups to assume the responsibility for maintaining a particular stretch of trail. The work is done on a volunteer basis and can be very informal or highly organized. The Forest Service provides tools and expertise, and the volunteers the labor. The program has a strong philosophical appeal to hikers, who thus become supporters and participants in the preservation of the forests. The response has been particularly strong in the Sandia District of the Cibola National Forest and in parts of the Lincoln, Tonto, and Coronado National Forests. [20] A somewhat similar volunteer effort has been the "Eagle Watch" program, in which individuals volunteer their time, or sometimes receive a small stipend, to camp near a mated pair of bald eagles to protect them during the nesting period. The Coronado National Forest and the Tonto National Forest have been especially successful with the Eagle Watch program. [21]

Job Corps

In recent decades, the Forest Service has attempted to duplicate the great work of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) during the 1930's through the federally funded job Corps Program, which, like the CCC, seeks to provide disadvantaged and unemployed youths with work opportunities. However, service records suggest that the environmental work done by the Job Corps has been meager compared to the earlier CCC. A common complaint was that Job Corps youths were difficult to supervise and disinclined to physical labor. [22] Nevertheless, the Job Corps has been effective in restoring the dignity and sense of worth of many young people. Through such programs, the magic of the forests has become accessible to more Americans than ever before.

A trail specifically designed for visually and mobility impaired people has been constructed in conjunction with the Cienega Picnic Ground in the Sandia Ranger District of the Cibola National Forest. The Ten X campground in the Kaibab is also designed for the physically handicapped. Programs are also conducted for blind youngsters who are taken into the forest and given the experience of hearing and feeling part of the forest environment. [23] The Forest Service indirectly facilitates the recreational use of the forests by leasing land or "use" to individuals or corporations under Special Use Permits for the operation of horseback riding stables, backcountry packing, jeep trips, boating, fishing, and hunting.

Providing Conveniences

Increased public use requires providing such assumed conveniences as drinking water and sewage disposal facilities, difficult and costly undertakings in remote forested areas. Primitive campgrounds dispense with the amenities of civilization, but pollution controls are imperative everywhere. The new emphasis on dispersed recreation tends to ameliorate damage to flora and fauna in the national forests. [24]

Most of the visitors to the national forests now come in automobiles, and many never leave their vehicles during their visit. Even these have been accommodated with roadside turnouts and parking spaces at scenic vistas or unusual geologic formations. Camera buffs are counseled and encouraged by signs and brochures. [25] The number of beautiful and memorable views in the national forests of the Southwestern Region are legion.

There is magic in the forests of the Southwest, and it is a magic that tempts us. It is the Forest Service's mission in the Southwestern Region to preserve and protect, so that those who have not yet come this way may do so, and may share with the travelers, explorers, and inhabitants of the Southwest that sense of wonder and magic. This job has not been an easy one, in part because the magic and wonder are defined in different ways by different people. The job has become increasingly difficult in modern times because the Forest Service is not only concerned with multiple uses and sustained yields, but increasingly with a variety of public opinions from within and outside the Southwest. The forests, their uses, and the people who use them have changed. They will continue to do so, and the work of the Forest Service in protecting this heritage for the people will never be finished.

Reference Notes

1. Official Map, USDA, Forest Service, Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands (1980).

2. Official Map, USDA, Forest Service, Magdalena Ranger District, Cibola National Forest (1977).

3. Southwestern Region News (February 1986), p. 3.

4. Louis Cottam, interview, August 16, 1985.

5. Walter G. Mann, Forest Supervisor, "The Kaibab Deer: A Brief History and the Present Plan of Management" (Kaibab National Forest, 1931, 1936, 1941), pp. 14-27; Roger S. Bumstead, personal interview, August 8, 1984, Albuquerque, NM. Bumstead, a wildlife biologist with the Forest Service, worked for the State of Arizona Wildlife Department in the 1930's and 1940's.

6. A common method to coordinate State and Forest Service activities is the so-called Memorandum of Understanding.

7. Summary of Big Game Animals in National Forests (Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service, 1921). This original brief report in 1920 has developed into 154 detailed pages; Wildlife and Fish Habitat Management in the Forest Service (Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service, 1985); Bill Zeedyk, Director of Wildlife, personal interview, August 19, 1985, Albuquerque, NM.

8. Roger S. Bumstead, interview, August 19, 1985.

9. Zeedyk, interview, August 19, 1985; Summary of Big Game Animals in National Forests in 1920 and yearly counts since that time.

10. Wildlife reports, first published in 1920, have been published annually since 1924. See note 7.

11. Bumstead, interview, August 8, 1984.

12. Zeedyk, interview, August 19, 1985. The last several wildlife reports indicate that the decline of antelope populations may have been arrested.

13. Facts About the National Forest System in the Southwest, p. 8.

15. E.J. Dyksterhuis, "Notes on the Origin of Range Science," Rangelands (December 1980), p. 3-4; D.M. Lang, "Reconnaissance of the Kaibab National Forest," unpublished manuscript, 1909 (filed at the Kaibab National Forest, 1685).

16. The observations are largely those of the author (Victor H. Treat), and in part derived from maps and conversations as well as extensive travel.

17. Charles F. Wilkinson, The Greatest Good for the Greatest Number ... p. 12. University of New Mexico archives, Albuquerque, NM.

18. The amount varies between 10 and 25 percent.

19. Interview with Floyd A. Thompson (Trails and Volunteers), Albuquerque, NM, August 20, 1985.

20. Ibid.; and see Adopt A Trail Handbook (Albuquerque, NM: USDA Forest Service, Southwestern Region, 1984).

21. Interview with Larry Forbis, wildlife specialist, Phoenix, AZ, August 18, 1985.

22. "Job Corps: Report," Federal Records Center, Fort Worth, TX, 095-72A0871.

23. Another example of a trail for the visually handicapped is the La Pasada Encantada Trail from the Sleepy Grass Campground on the Lincoln National Forest.

24. Interview with Dick Spray, Recreation Staff, Region 3, re: Dispersed Recreation, Albuquerque, NM, August 19, 1985.

25. Interview with Lou Armijo, Public Affairs Specialist, Albuquerque, NM, August 20, 1985.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

region3/history/chap17.htm

Last Updated: 22-Feb-2008