|

Timeless Heritage: A History of the Forest Service in the Southwest |

|

Chapter 4.

Establishment of Forest Reserves and Land Status Changes

The General Land Law Revision Act of 1891, commonly called the Creative Act of 1891, provided for the setting aside of forest reserves. The forest reserves, and later the national forests, were proclaimed as soon as they had been surveyed, and the President had become convinced that such action was in the public good. Gifford Pinchot did his share of convincing. Presidential creations came fast and furious in the early days. Twenty-five forest reserves and four national forests were proclaimed in the Southwest Territory from 1892 to 1907 (see table 1).

Table 1. Initial forest reserves and national forests in the Southwest

| Name | State | Citation | Date Established |

Present national forest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest Reserve | ||||

| Pecos River | NM | 22 stat 998 | 1/11/1892 | Santa Fe |

| Grand Canyon | AZ | 27 stat 1064 | 2/20/1893 | Kaibab & Coconino |

| Prescott | AZ | 30 stat 1771 | 5/10/1898 | Prescott |

| San Francisco Mtns | AZ | 30 stat 1780 | 8/17/1898 | Coconino |

| Black Mesa | AZ | 30 stat 1782 | 8/17/1896 | Coconino & Sitgreaves |

| Gila River | NM | 34 stat 3126 | 3/2/1899 | Gila |

| Santa Rita | AZ | 32 stat 1989 | 4/11/1902 | Coronado |

| Santa Catalina | AZ | 32 stat 2012 | 7/2/1902 | Coronado |

| Mount Graham | AZ | 32 stat 2017 | 7/22/1902 | Coronado |

| Lincoln | NM | 32 stat 2018 | 7/26/1902 | Lincoln |

| Chiricahua | AZ | 32 stat 2019 | 7/30/1902 | Coronado |

| Pinal Mountains | AZ | 34 stat 2991 | 3/20/1905 | Tonto |

| Tonto | AZ | 34 stat 3166 | 10/3/1905 | Tonto |

| Portales (rev. 1907) | NM | 34 stat 3178 | 10/3/1905 | Not NF |

| Jemez | NM | 34 stat 3182 | 10/12/1905 | Santa Fe |

| Mount Taylor | NM | 34 stat 3239 | 10/5/1906 | Cibola |

| Gallinas | NM | 34 stat 3243 | 11/5/1906 | Cibola |

| Magdalena | NM | 34 stat 3245 | 11/5/1906 | Cibola |

| Peloncillo | NM | 34 stat 3248 | 11/5/1906 | Most not NF |

| San Mateo | NM | 34 stat 3249 | 11/5/1906 | Cibola |

| Baboquivari | AZ | 34 stat 3251 | 11/5/1906 | Not NF |

| Huachuca | AZ | 34 stat 3255 | 11/6/1906 | Coronado |

| Manzano | NM | 34 stat 3257 | 11/6/1906 | Cibola |

| Taos | NM | 34 stat 3262 | 11/7/1906 | Carson |

| Tumacacori | AZ | 34 stat 3263 | 11/7/1906 | Coronado |

| Big Burros | NM | 34 stat 3274 | 2/6/1907 | Gila |

| National Forest | ||||

| Guadalupe | NM | 35 stat 2124 | 4/19/1907 | Lincoln |

| Sacramento | NM | 35 stat 2127 | 4/24/1907 | Lincoln |

| Dragoon | AZ | 35 stat 2135 | 5/25/1907 | Corondao |

| Verde | AZ | 35 stat 2170 | 12/30/1907 | Tonto, Coconino & Prescott |

Source: Establishment and Modification of National Forest Boundaries, A Chronological Record, 1891-1985, Lands Staff, USDA Forest Service, Washington, DC (Draft, December 1985).

Gifford Pinchot, in Breaking New Ground, refers to the activity of boundary examiners. A.O. Waha, in his memoirs recorded at the request of Gifford Pinchot in 1940, included the following comments on boundary examination in the Southwest:

1907 was the year of feverish activity in establishing additional National Forests while President Theodore Roosevelt was still in office and all that was required was a Presidential Proclamation. Fast work was required. Boundary examiners assigned to the southwest, W.H.B. Kent (Whiskey Highball, as we called him) and Stanton G. Smith, got in their "good licks" and it has always been amazing to me how well the boundaries were fixed in view of the extensive character of their examinations. [1]

The forest reserves were usually set aside several years before they were inventoried. Four of the first ten forest reserves proclaimed in the Southwest were inventoried by the USDI Geological Survey under authorization of the Sundry Civil Appropriations Bill, signed by President McKinley on June 4, 1897. The order of these inventories was: the San Francisco Mountains (inventoried in 1901/1902 and published in 1904), the Black Mesa (inventoried in 1902/1903 and published in 1904), the Lincoln (inventoried in 1903/1904 and published in 1904), and the Gila River (inventoried in 1903 and published in 1905). The four publications were works of art, with colorful maps, numerous photographs, and tabulations, and they were printed on fine paper. [2]

|

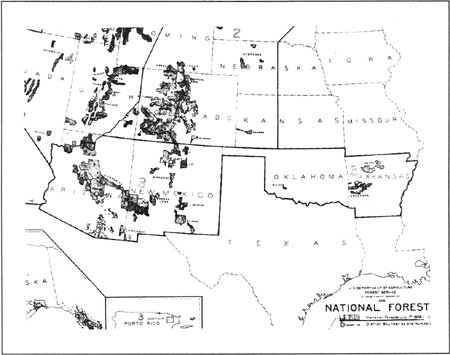

| Figure 3—Boundaries of old district 3 (1908). (click on image for a PDF version) |

After the transfer of the forest reserves to the Department of Agriculture and the creation of the Forest Service, the inventories were made by Forest Service personnel. The forest inventories were called reconnaissances. They were not printed, but typewritten, often with pasted-in photographs. The format of each report was quite similar. A section included the history of the survey and an introduction listing the history, location, area, topography, settlements, and industries within the boundary of the reserve. A forest description followed, including a list of the forest types, and species and stand tables. A chapter on lumbering was followed by one on management. The final section was the timber estimate. Usually there was an appendix. [3]

These reconnaissances became more formal documents by the second decade of the century. The Forest Service established field methods for the reconnaissance studies. A tier of from three to six sections of land, running either north to south or east to west, was assigned to one man for two days' work or to two men for one day's work. The person made one sample per "forty" or quarter quarter-section. All estimates were visual. Essential topographic features were mapped en route. The report included the map, the number of thousand board feet for each species yielding lumber, the stand (in cords) of species not yielding lumber, and the character of the reproduction. [4]

Timber Reconnaissance

In the minutes of an Apache National Forest ranger meeting, held at Springerville, AZ, September 8-14, 1910, Aldo Leopold discussed timber reconnaissance.

... Reconnaissance work consists of making an estimate of all timber and making a map of the country as we go over it to estimate the timber.... The method is rough. It consists of going once through each 40-acre subdivision and making an estimate of the timber in that 40 acres.... In surveyed ground, the method is to start from one of the section corners.... The maps made in the field are of course just a rough sketch. They include the location of all streams, trails, roads, timber lines, fences, etc.... and the topography is put in by contours.... The surveys in many places are very old, and I think there is a big danger of the corners established becoming obliterated. ... Area covered by reconnaissance last year was 65,000 acres. Area covered to date, 170,000 acres; 200,000 acres remaining uncovered ... by the time the work is finished, the cost of the work may be reduced to 1-1/2 cent [per acre].... By the reconnaissance system, a green man can do surprisingly accurate cruising.

The best means of arriving at a reasonably accurate estimate of a forty is to compare it mentally with plots whose stand of timber has been determined by more exact and detailed methods. [5]

During the evening, the day's work was transferred to form 332, the reconnaissance section plat. The form was on fine bond paper so that blueprints could be made. When a township was completed, the forms were sent through the supervisor to the district forester.

Changes in Land Status

Changes of land from or to national forest status have occurred for legal or legislative reasons, and for purposes of more efficient administration. Boundaries of national forests often changed in the early years when surveys were completed. This process was called land classification. During the period 1909-13, for instance, classification work eliminated land in the Rio Grande, Jemez, and Carson National Forests in District 3. National Forest System land in Arizona and New Mexico changed in and out of classification as national forest, national park, national monument, and Indian reservation. There did not seem to be any consistency in how it happened. Highlights of the chronological events in a few national forest land cases show the trend.

In 1909, national forests were enlarged or created by land appropriations from Indian reservations: for instance, land from the Jicarilla Apache Indian Reservation was added to the Carson National Forest; lands from the Zuni and Navajo Indian Reservations were used to establish the Zuni National Forest; and land from the White Mountain Apache Indian Reservation went to the Apache National Forest. In 1910, presidential proclamations added and eliminated land in many of the national forests in Arizona and New Mexico. In 1912 the lands that were taken from Indian reservations in 1909 were returned.

A limited amount of change in national forest boundaries occurred during 1914-21. The Bandelier National Monument was created from Santa Fe National Forest land in 1916 with the support of the forest supervisor. Land from the Navajo Indian Reservation was added to the Manzano National Forest in 1917. In 1919 the Grand Canyon National Park, comprising 606,720 acres, was carved from the Tusayan National Forest.

Forest Exchange Act

The General Forest Exchange Act (42 Stat. 465), enacted in March 1922, authorized the Forest Service to consolidate forest lands, and authorized exchanges to acquire privately owned forest land lying within the boundaries of national forests for government-owned land or stumpage on any forest in the same state. The Act was amended and extended in 1923, and again in 1926 when it authorized exchange of Arizona timber and land for private lands in San Miguel, Taos, and Mora Counties (the Mora Grant). An amendment in 1928 authorized the use of land and timber to be exchanged for grant lands adjacent to the Carson, Santa Fe, and Manzano Forests in New Mexico. It was also amended in 1929 and 1935. In 1925 another act authorized the acquisition through exchange of parts of the Santa Barbara Grant in New Mexico.

During the 1920's, there were additions and eliminations of land from several of the national forests in the Southwestern District. In 1925 parts of two military reservations were transferred to national forest status. In 1927 lands were exchanged between the Grand Canyon National Park and the Kaibab and Tusayan National Forests. In the 1930's, changes in national forest boundaries continued. The Bandelier National Monument gained over 25,000 acres of land from the Santa Fe National Forest in 1932. In 1935 the Zuni Indian Reservation was awarded land that had been in the Cibola National Forest. In 1937 the Montezuma Castle National Monument received land in a transfer from the Coconino National Forest. The following year, land was transferred from the Coronado National Forest to the Chiricahua National Monument, and administrative control of an area (but not the land) in the Coconino National Forest was conveyed to the Walnut Canyon National Monument. Similarly, many of the areas designated as national parks and monuments were set aside as such but continued to be administered by the Forest Service until the 1930's.

The rate of land transfers slowed during World War II but picked up again at the end of the decade of the 1940's, including more land transferred from the Coconino National Forest to the Montezuma Castle National Monument. The Tonto National Monument and Gila Cliff Dwellings were carved from the Tonto and Gila National Forests.

A highlight of land transactions included a land exchange in Arizona in 1952, when land was taken from the Coronado National Monument. The Luero Mountains in New Mexico were taken from the Gila in July 1953, and the Chupadera Mesa from the Cibola National Forest in June 1954. Region 3 acquired the Rio Grande Grant, the San Diego Grant, the Hondo Tract, and hundreds of acres of State lands in exchanges in the 1950's and 1960's. In April 1968, Mount Powell and the Shrub Gulch Division were taken from the Cibola National Forest. In 1975 some land was transferred from the Kaibab National Forest to the Havusupai Tribe and some to the Grand Canyon National Park. Thus, national forest boundaries and the supervision of federal lands are in a constant state of change. In the process of change, the size and integrity of the Southwestern forests have generally been enhanced.

In the 1980's the policy has been to "emphasize land exchanges dealing with schools, expanding communities, and those that will result in increased timber production and watershed protection." [6] Of the 12 national forests in the region in 1982, exchanges occurred on nine, purchases occurred on two, and donations of land were made to four, including 100,000 acres to the Carson National Forest (the Villa Videl unit of Vermijo Ranch) by the Pennzoil Corporation in 1982. [7] Land exchanges have kept the Southwestern Region personnel fully occupied since its establishment and have contributed to the need to reorganize the administrative units of the forests.

Ranger Districts Begun

On January 1, 1907, the larger national forests were reorganized by dividing them into north and south divisions. Ranger districts at the time were not well defined and the ranger headquarters was usually where the ranger lived. Not until 1907-09 did the Forest Service begin to build ranger stations and divide the forests into clearly defined ranger districts. [8] Executive orders were issued in July 1908, making important changes in the boundaries of the national forests in New Mexico and Arizona and rearranging the names and the headquarters towns. The explanation was that "the object of the work is to equalize the area of administrative units and to arrange their boundaries in such a manner as to promote the most practical and efficient administration of the Forests. [9] In New Mexico, the following national forests were in place: Alamo, Carson, Datil, Gila, Lincoln, Magdalena, Manzano, and Pecos. In Arizona, the following national forests were in place: Apache, Chiricahua, Coconino, Coronado Crook, Garces, Kaibab, Prescott, Sitgreaves and Tonto. [10] Prior to this time, there had been additional national forests, some quite small.

Another reorganization took place in 1915, consolidating the Jemez and Pecos National Forests into the Santa Fe National Forest. In 1930 there were 14 national forests in the region: the Alamo, Apache, Carson, Coconino, Coronado, Crook, Datil, Gila, Lincoln, Prescott, Santa Fe, Sitgreaves, Tonto, and Tusayan. In 1933, the Kaibab National Forest was transferred from the Intermountain Region to the Southwestern Region and combined with the Tusayan. In 1953 the Crook National Forest was dissolved and its lands were transferred to the Coronado, Tonto, and Gila National Forests. [11]

A major change in 1954 was the transfer of administration of the national grasslands within the Department of Agriculture from the Soil Conservation Service to the Forest Service. Thus, the Region gained 12 national grasslands in New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas. Effective July 1, 1958, there were additional changes of divisions and ranger districts from one national forest to another in the region. Land utilization tracts were transferred to the Carson and Santa Fe National Forests in 1962 and given national forest status. The Amarillo Supervisor's Office for the national grasslands was abandoned in the 1970's, consolidating the districts with the Cibola National Forest, thereby leaving the only national forest presence in west Texas at Texline. Two districts were transferred to the Southern Region (region 8). [12]

In 1974 the Apache and Sitgreaves National Forests were merged administratively, to form the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest. Ten years later a large parcel of land was transferred from the Santa Fe National Forest to the Cochiti Indian Reservation. In 1986, there were 12 national forests in the region: the Apache, Carson, Cibola, Coconino, Coronado, Gila, Kaibab, Lincoln, Prescott, Santa Fe, Sitgreaves, and Tonto. "Interchange" proposals presented early in 1985 could result in additional realignments of national forests in the region. [13]

Special Designations of National Forest

Land

Although "multiple use" is the overriding concept of management of National Forest System lands, over the years special uses have proliferated. Quite often, the special use is for a very limited amount of land but requires considerable time to process and administer. Typical early uses included "pastures to be used in connection with homesteads and ranching units, stockmen's cabins used in connection with grazing permits, irrigation ditches, reservoirs, telephone lines, power lines, summer homes, and so forth." Recent visitors to the national forests in Arizona and New Mexico see the tops of peaks being used as electronic transmission sites, an important but not esthetically pleasing use of the land. [14]

Wilderness

Significant special designations for one of the multiple uses, often limiting or prohibiting one or more of the other multiple uses, have taken place in the region as well. "Wilderness" was one of these. The first wilderness area on any national forest in the nation was designated in 1924 on the Gila National Forest, at the urging of Aldo Leopold. [15] By 1945, wilderness designations had been expanded to the following: Mazatzal, Tonto National Forest (established 1933, approved 1940); Superstition, Tonto National Forest (established 1939, approved 1940); and Gila, Gila National Forest, designated in 1924 (established 1933, approved 1935). In addition, by 1957, there had been established three wild areas in Arizona and two in New Mexico, each under 5,000 acres. Here logging was discouraged and range use was continued on some and changed to a more conservative posture on others. Also, six primitive areas, two in New Mexico and four in Arizona, were established during 1932-35. [16]

By 1983 all these areas except the Blue Range Primitive Area had been listed as "Wilderness System"; there were 10 in Arizona (552,784 acres) and 17 in New Mexico (1,410,690 acres). In addition, there are designated "wild and scenic rivers" on the national forests in the Southwestern Region. The Chama River Canyon in New Mexico has already been set aside. During 1983 the Forest Service completed studies of portions of three rivers in Arizona, the Verde, Salt, and San Francisco. The only river designated as wild and scenic in New Mexico is the section of the Rio Grande that passes through and is adjacent to the Carson National Forest. [17]

Wildlife Refuges

Wildlife refuges were designated as portions of national forests where hunting is prohibited. The most famous such refuge in the region was the Grand Canyon Game Preserve, set aside in 1906 by President Theodore Roosevelt. It occupied most of the North Kaibab. Hunting was again permitted after severe habitat damage occurred when the number of animals increased drastically. In addition, several experimental forests have been established for forestry research. The Fort Valley Experimental Forest established on the Coconino National Forest in 1908 was the first in the United States. Natural areas devoted to scientific research also were established, including the Santa Catalina on the Coronado in 1927 and the West Fork of Oak Creek and San Francisco Peaks on the Coconino, two on the Coronado National Forest, and one on the Santa Fe National Forest in the 1930's. Another, the Gus Pearson Natural Area within the Fort Valley Experimental Forest on the Coconino, was established in the 1950's. Two experimental ranges, independent of any national forest, the Santa Rita in Arizona and the Jornada in New Mexico, have been functioning for many years. The C. Hart Merriam Scenic Area, the first scenic area in the Southwestern Region, was designated on the Coconino National Forest in 1968. The University of New Mexico has maintained a research area of 10,000 acres on the Santa Fe National Forest since 1930. [18] Special uses, of course, limit the Forest Service's practice of multiple use to some extent.

Keeping Track of National Forest Land and

Boundaries

Two primary concerns relating to lands have plagued National Forest System administrators in the Southwest: (1) determining and maintaining the legal boundaries of the national forests, and (2) attempting to consolidate the lands into more manageable complete blocks by land exchange or purchase. In the early years, many changes in national forest boundaries occurred as inaccurate land surveys and nebulous descriptions of Mexican and Spanish land grants were cleared up. The national forests in the Southwest have dropped and added lands on a more or less regular basis during the decades. Because of laws and special regulations, arrangements for exchange or purchase of land are quite complicated. [19]

Fortunately, the Southwestern Region had people in charge of lands who were talented and dedicated to their task. As a result, by June 30, 1969, 520 land exchange cases had been processed in the region, "by which the United States has acquired 1,293,109 acres and granted in return 831,219 acres of land and 450,000 bd. ft. of timber." Some of the individuals responsible were Zane Smith (whose father was a ranger in District 3 and whose son became a regional forester), Dean Cutler, Sim Strickland, and Alan Watkins. [20] There have been others, of course, who worked hard and effectively on this difficult and highly successful program.

Of particular concern was the proper survey of land lines, especially those of the Spanish and Mexican land grants. The surveys were often confusing, and "use lines" had changed. A large collection of correspondence and reports is in the files of the Carson National Forest, dating between 1911 and 1921, concerning the Maxwell Grant in northern New Mexico, specifically its western boundary and the eastern boundary of the Carson National Forest. Since the boundary line had never been surveyed, the problem seemed insoluble at that time. It was finally settled in favor of the owners of the neighboring Mora Grant by the United States Supreme Court.

The Forest Service acquired two Spanish grants in northern New Mexico through special legislation passed by Congress in 1922, 1925, and 1928. The prolonged efforts of the Forest Service to obtain the Rancho del Rio Grande Grant in Taos County, New Mexico, comprising 91,813 acres all in one piece, granted in 1795 and patented in 1909, has been less successful. According to Dean Cutler, a deal to acquire the grant in the 1930's and another after World War II fell through when small differences in appraised prices and asking prices could not be reconciled. Another try in the 1960's could not be consummated when the new owner of the grant wanted cash rather than other lands and timber. A try at a "third party" to buy the lands and then exchange them also could not be worked out. Finally, the director of the division of lands, Zane Smith, and his staff put together a complicated deal involving 57 landowners, mostly in the area of the Cibola National Forest, to accomplish the exchange of 52,870 acres of the grant (all in one piece) for National Forest System lands in various parts of New Mexico, including tracts having real estate or development value around communities in the Albuquerque area. [21]

There has been a concentrated effort by Forest Service administrators to consolidate lands within the exterior boundaries of the national forests. The ramifications of exchange have been extensive, especially the legal and appraisal aspects. For instance, detailed calculations are necessary in the appraisal portion of acquisition/exchange in order to satisfy the General Accounting Office that the land being added and the timber or land being relinquished are of equal value. This requires administrators to fix priorities in use of people and funds and in the selection of areas to which available resources for land exchange will be devoted.

One particularly complicated negotiation began at the time of the original proclamation of the forest reserves, as reported by Fred Eldean, a businessman of Scottsdale, AZ, in 1981. This case involved 98,000 acres of land that were proclaimed as part of the old Black Mesa Forest Reserve but that had already been granted to the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad at the time of the proclamation. In 1866 Congress granted a right-of-way through government land to the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad. Since the government had limited funds but large amounts of land, it granted every other section of land for 40 miles on either side of the proposed line of the future railroad. In case there was previous ownership or subsequent Indian and military withdrawals within the strip, the railroad could be awarded "indemnity" lands within an additional 10-mile strip. The land in question lay within the 10-mile strip and was part of one million acres of land that the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad sold to the Aztec Land and Cattle Company at 50 cents per acre. The 98,000 acres, now on the Coconino and Sitgreaves National Forests, were not surveyed and thus could not be selected. According to Dean Cutler, the tale took a peculiar twist in the late 1930's and in 1940. [22]

During the late 30's, the land Office finally surveyed the area. Nearly everyone, including the railroad, had forgotten about the 10 mile strip. A lawyer, Cake by name, hadn't. He had worked for the Department of [the] Interior and remembered the law. He went to the A.T. & S.F. officials and told them about it. He said that he would get the land for them for half of the value involved. The officials formed a company and filed a claim on 98,000 acres of National Forest just before the Act of 1941 was passed which terminated the railroads' obligation to haul Government freight free or at reduced rates and eliminated their rights to select Federal land as recompense for building primary roads across the Country. [23]

The government claimed that the establishment of the forest reserve nullified this part of the railroad grant but an appeals court ruled its case invalid. In 1952 the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal by the government, thus ending the case.

During all the intervening years, these lands had been treated as national forests. Local interest favoring these lands remaining in the national forests was high and a Citizens' Committee recommended that Congress be asked to appropriate funds to purchase the lands and restore them to the national forests. Senator Hayden proposed such a bill, Senator Goldwater endorsed it, and the Senate approved it, but the House did not, apparently over a difference of $2.00 per acre in appraisals by the Forest Service and the General Accounting Office. Three private companies, Winslow Timber Company, Whiting Bros., and Southwest Lumber Mills, Inc., bought the land and timber from the Aztec Land and Cattle Company for $12.00 per acre, which was considerably more than either earlier federal appraisal. Before negotiations to purchase the land from the timber companies could be finalized, a California syndicate wanted to buy the 87,000 acres owned by Southwest Forest Industries (the new name of Southwest Lumber Mills, Inc.) for resale as small parcels. Finally, in a series of complicated deals, Eldean purchased the land and traded it to the Forest Service for other lands near Flagstaff and "peripheral areas to Scottsdale and Phoenix." [24] By 1981, some 65,000 acres had been exchanged. In summing up this case, Eldean said:

Thus a major portion of the U.S. Forest Service's objective in regaining the lands lost by court decision has now been regained. The basic integrity of the Forest has been preserved. The public good has been served. Private enterprise rendered a public service. The National Wildlife Federation presented a Conservation Organization award in the form of a statuette of a bighorn sheep to Page Land & Cattle Company. [25]

The difficult nature of land exchanges is expressed well by Dean Cutler, who wrote, "In lands work, we had many disappointments and I never celebrated until the deeds were all signed, title approved, and recorded. If the deal fell through, well, I had given it my best shot. Forget it and go on to the next case." [26]

Transfers of land from national forests, even for public purposes, have been viewed as disappointments by land administrators in the Southwestern Region. They view the transfer of public lands, long available for general public use and enjoyment, to exclusive use of a certain segment of the population, without offsetting recompense to the public, as contrary to the general public interest. This was the basic question in the transfer of two areas from the Carson National Forest to the Taos Indians, the Blue Lake area during the Kennedy administration, and the Rio Pueblo Drainage during the Nixon administration. [27] This transfer activity set a national precedent for interchange.

In 1985 came the proposed "interchange" between the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management, whereby western public lands administered by these agencies would be re-zoned for exclusive management by one of them, in order to effect cost-savings. However, the manner of disclosure—announcement by the Secretaries of Agriculture and the Interior only after the plan was finalized—was a shock to the constituents of each agency. Acceptance of the plan and its effects on the national forests in the Southwest are unknown at this time.

Control of Land Use Through Control of

Resources on the National Forests

The national forests have held a moderate proportion of the land and a major proportion of the non-agricultural renewable resources of the Southwest since their formation. The national forests in the Southwest affect the entire region, particularly relating to grazing, timber production, mining, recreation, and water resources. Eighty-five percent of land in Arizona and 94 percent of land in New Mexico were deemed suitable for livestock in 1945. In 1983 the National Forest System provided 25 percent of the rangeland grazing in Arizona and 9 percent in New Mexico. However, the influence of the national forests on the cattle industry is far greater than the acreage under national forest control. Since the National Forest System provides much of the summer range and some year-round grazing, regional administrators effectively determine the profitability of livestock industry operations in the Southwest. [28]

The Forest Service strongly influences timber management and timber harvests in the Southwest. In 1945, national forests in Arizona contained 70 percent of the sawtimber, 36 percent of the cordwood, and 65 percent of the timber land in the State. In the same year in New Mexico, 65 percent of the sawtimber, 40 percent of the cordwood, and 67 percent of the timber land in the State was inside the boundaries of the national forests. Two-thirds of the merchantable timber in Arizona and half of the merchantable timber in New Mexico are today within the national forests. [29] Recreation has been one of the most rapidly growing uses of the national forests.

In 1945 recreational use of the national forests was low, nearly 600,000 visitor-days in Arizona and over 300,000 in New Mexico. By 1983 recreation use had increased drastically to over 15 million visitor-days in Arizona and over 7 million in New Mexico. The National Forest System is the major recreational resource in the Southwest and provides about 40 percent of the total surface water available in the two States. [30]

National forests tend to dominate many aspects of life in Arizona and New Mexico. Considerable influence on the quality of life is exerted through the public ownership and planned management of National Forest System lands. How Forest Service personnel in charge of land and resources handle the ever-increasing—often conflicting—demands for uses, the utilization of timber, forage, and water, mineral and recreational resources, and the always important conservation of watersheds and the basic soil resources, in large measure, determines the contribution of national forests to citizens of the Southwest and of the Nation.

Reference Notes

1. Edwin A. Tucker unpublished manuscript, Region 3, Albuquerque, NM, p. 147.

2. John B. Leiberg, Theodore F. Rixon, and Arthur Dodwell, Forest Conditions in the San Francisco Mountains Forest Reserve, Arizona, Prof. Pap. 22 (Series H, Forestry 7) (Washington, DC: USDI Geological Survey, 1904), 95 pp.; F.G. Plummer, Forest Conditions in the Black Mesa Forest Reserve, Arizona, Prof. Pap. 23 (Series H, Forestry 8) (Washington, DC: USDI Geological Survey, 1904), 62 pp.; F.G. Plummer and M.G. Gowsell, Forest Conditions in the Lincoln Forest Reserve, New Mexico, Prof. Pap. 33, (Series H, Forestry 11) (Washington, DC: USDI Geological Survey, 1904), 47 pp.; T.F. Rixon, Forest Conditions in the Gila River Forest Reserve, New Mexico, Prof. Pap. 39 (Series H, Forestry 13) (Washington, DC: USDI Geological Survey, 1905), 89 pp.

3. Another source lists streams, dry runs, and ridges as well as areas and forest types.

4. Tucker manuscript, pp. 509-511.

5. "Outline of Field Methods Used in Reconnaissance Studies," File Prescott-Recon-Studies. USDA, Forest Service, Southwestern Region, Prescott National Forest, p. 2.

6. Facts About the National Forest System in the Southwest (Albuquerque, NM: USDA, Forest Service, Southwestern Region, 1983), p. 3.

12. William D. Hurst, Bosque Farms, NM, letter to Henry C. Dethloff, College Station, TX, January 2, 1986.

13. They are still referred to as being separate forests in literature published by the Southwestern Region; i.e., "The Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests are located in the White Mountains of east-central Arizona." Facts About the National Forest System in the Southwest (1983), p. 18.

14. Edwin A. Tucker and George Fitzpatrick, Men Who Matched the Mountains: The Forest Service in the Southwest (Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service, 1973), p. 242. A reviewer noted that most ditches predated the establishment of national forests and were seldom permitted after the Forest Service assumed control. Another reviewer added that, in addition to telephone lines and power lines, rights-of-way were granted for roads and pipe lines. Later uses include ski areas.

15. The Forest Service has had three types of areas where solitude was the primary activity: primitive, wild, and wilderness. An explanation of these designations has been made by C. Frank Brockman. "Me difference between a wilderness and a wild area in the national forests is size. Wilderness areas must contain more than 100,000 acres, wild areas are between 5,000 and 100,000 acres. In a number of USDA Forest Service regions an original classification of primitive area still applies to certain lands although the authority by which such areas were designated (Regulation L-20) has been rescinded by the Secretary of Agriculture and replaced by the more recent classifications of wilderness area (Regulation U-1) and wild area (Regulation U-2). Primitive areas established and still in existence under the old regulation retain their status until revoked by the Chief Forester." C. Frank Brockman, Recreational Use of Wild Lands (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1959), pp. 166-167.

16. Samuel Trask Dana and Sally K. Fairfax, Forest and Range Policy (New York: McGraw-Hi11, 1980), p. 382.

17. Facts, National Forests of Arizona and New Mexico (1958), p. 10. Tracking whether an area was wilderness, wild area, or primitive area is difficult; the regional "facts" publication in 1945 (p. 39) lists these differently than the 1958 edition. On the renaming of areas set aside, as alluded to in the previous footnote, William D. Hurst wrote this: "It should be noted that the Blue Range Primitive Area which was established early in the Wilderness and Primitive Area designation, was not made a Wilderness with the remainder of the Primitive Area units in New Mexico and Arizona. For political reasons it remains a Primitive Area." William D. Hurst, Bosque Farms, NM, letter to H.C. Dethloff, November 14, 1985, p. 1.

19. Frankie McCarty, Land Grant Problems in New Mexico (Albuquerque, NM: n.p. 1969), reprinted from Albuquerque Journal, September 28-October 10, 1969, p. 1.

20. Tucker and Fitzpatrick, Men Who Matched the Mountains, p. 242.

21. Ibid., pp. 241-242. According to Rowena Martinez, ed., Land Grants in Taos Valley (reprinted in part from Publ. No. 2, Taos County Historical Society, 1968), p. 6.

22. Dean A. Cutler, letter to H.C. Dethloff and R.D. Baker, May 16, 1985, p. 1.

24. Fred Eldean, "The Case of the 98,000 Acres," speech to a historical group at the Corral of Scottsdale, Arizona, March 25, 1981, p. 13. [In files of Coconino National Forest.]

26. Dean A. Cutler, letter to H.C. Dethloff and R.D. Baker, May 16, 1985, p. 1.

28. USDA Forest Service, An Assessment of the Forest and Range Land Situation in the United States, For. Res. Rep. 22 (Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service, 1981), pp. 1-352; Facts About the National Forest System in the Southwest (1983), p. 10.

29. National Forest Facts, Southwestern Region, Arizona and New Mexico (Albuquerque, NM, 1945), p. 14; USDA Forest Service, Forest Statistics of the U.S., 1977 (Washington, DC, 1978), pp. 36, 38.

30. USDA Forest Service, Southwestern Region, National Forest Facts, p. 39; Facts About the National Forest System, pp. 28-29.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

region3/history/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 22-Feb-2008