|

Timeless Heritage: A History of the Forest Service in the Southwest |

|

Chapter 6.

The Pioneers-Establishing the Concept of Forestry in the Southwest, 1905-24

Ranching, lumbering, and mining were well established in the Southwest long before the earliest foresters or conservationists made their appearance. Ranchers grazed their cattle and sheep, loggers cut timber and chopped firewood, and prospectors explored for gold, silver, and copper on the public domain, almost as a right with no one disputing their course. The General Land Office of the Department of the Interior, which had jurisdiction over the Federal lands, was primarily interested in selling them. Anyone could buy land, usually at the minimum price of $1.25 per acre, either in large or small quantities. Homestead laws were generous, and settlers could claim 160 acres for each adult member of their family. Various special laws, such as the Timber Culture Act, and even more subterfuges enabled businessmen and corporations to acquire large blocks of land without paying even at the minimum price. Ranchers, accustomed to free use of the range, preferred to retain open access to the resources of the public domain-grass, water, timber, and minerals. They protested bitterly when Federal regulations curbed their frontier attitude.

In like manner, ranchers, loggers, and others also invaded the railroad lands, taking what they wished and giving no thought to the long-range future of the region. The railroads, particularly the Santa Fe and the Southern Pacific, had few men to patrol their lands and found local opinion solidly against them when and if they attempted to prosecute trespassers for misappropriating property. This state of affairs was normal in the territories of Arizona and New Mexico for the last 50 years of the 19th century, from American annexation in 1848 to 1900. During this time the population had increased from an estimated 62,000 inhabitants to about 320,000, and a modern rail system had been built. The Southwest was no longer frontier, and its resources required protection and conservation to prevent their dissipation and exhaustion.

Act of 1891

Recognizing the rapid taking of the public domain by private individuals and the even more rapid depletion of its timber resources, Congress in 1891 passed a General Land Law Revision Act. This gave the President authority to set aside and reserve any part of the public lands, wholly or partly covered with timber, as public reservations. "He shall, by public proclamation, declare the establishment of such reservations and their limits" (26 Stat. 1103). Acting on this authority, President Benjamin Harrison established the Pecos River Forest Reserve in 1892 and the next year proclaimed the establishment of the Grand Canyon Forest Reserve. These were the first Federal forest reserves set aside in the Southwest and provided the beginnings of the National Forest System in the region.

During the next ten years, Presidents Cleveland and McKinley set aside additional forest reserves in the Southwest totaling over 10 million acres. The Department of the Interior, which had jurisdiction over forest reserves, appointed John D. Benedict as the first forest superintendent for the Southwestern District in 1897. He was followed by William H. Buntain (1899-1900) and Isaac B. Hanna (1900-05). None of these men, nor the supervisors under them, were trained foresters but rather were political appointees of the Secretary of the Interior. Perhaps typical was Forest Supervisor R.C. McClure who, as described by contemporaries, habitually dressed in a Prince Albert coat, flowing-end black bow tie, gray checked trousers, polished boots, and a broad-brimmed black felt hat. He was usually found at his office, often with his feet propped on the desk—hardly the image of an active forest supervisor. [1]

Division of Forestry

In the meantime the U.S. Department of Agriculture had created a Division of Forestry (1881) headed by Franklin B. Hough, who was succeeded in 1883 by Nathaniel E. Egleston. In 1886 German-trained forester Bernhard E. Fernow became head. Fernow sought to get authorization for a survey of the forests in the public domain to be followed by Congressional legislation to provide a system to manage and protect the reserves. Cleveland's Secretary of the Interior Hoke Smith appointed the National Academy of Science (NAS) in 1896 to conduct such a survey, which resulted in Cleveland's proclamation in 1897 setting aside an additional 21 million acres of forest reserves. The study led to the Organic Administration Act of 1897 (30 Stat. 34-36), which established standards for the use and protection of the Nation's forest reserves. Cleveland's successor, William McKinley, was friendly to conservationists' goals and issued proclamations setting aside the Prescott, Black Mesa, and Gila River Forest Reserves in the Southwestern District. In 1898 Gifford Pinchot succeeded Fernow as Chief of the Division of Forestry in the U.S. Department of Agriculture. [2]

Pinchot, a prominent leader of the American conservation movement, was the driving force in the development of the Forest Service. It was Pinchot who preached the need for professionally trained foresters to manage the Nation's forest reserves and secured the upgrading in 1901 of the forestry office to the status of bureau.

Pinchot also convinced Theodore Roosevelt that the entire forest reserve system should be transferred to the Bureau of Forestry in the Department of Agriculture. It was irrational, he contended, that the corps of trained foresters should be in the Department of Agriculture but the public lands should remain in the hands of the politically oriented Department of the Interior. After Roosevelt succeeded McKinley as President in September 1901, he accelerated the designation of forest reserves in the Southwest, setting aside Mt. Graham, Santa Rita, Jemez, Mt. Taylor, Lincoln, Magdalena, Apache, and other forest reserves.

|

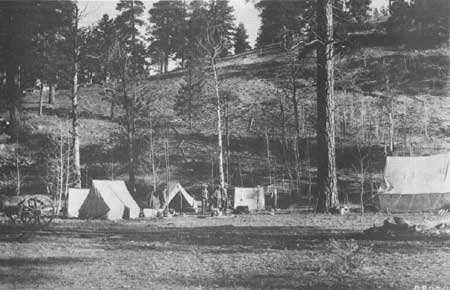

| Figure 5.—Ranger conference camp, Coconino National Forest, about 1910. |

The Transfer Act

At Roosevelt's urging, Congress in 1905 passed the act transferring the forest reserves from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Agriculture (33 Stat. 628). The same year the Bureau of Forestry became the Forest Service and Pinchot the Chief Forester. A letter from Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson to Pinchot outlined the President's directives and called for the Forest Service to bear in mind that all land must be devoted to its "most productive use for the permanent good of the whole people," and not for individuals or special interests. The resources should be "wisely used" for the "greatest good of the greatest number" in the long run. [3] Thus began the professional management of the Nation's forests.

Among Pinchot's first appointments to the Southwest was Arthur C. Ringland, who had worked for Pinchot as a student assistant in 1900 and absorbed some of his chief's enthusiasm and ardor for forest conservation. He entered Yale Forestry School in 1903 and graduated with a master's degree in forestry in 1905. Pinchot assigned him to the Lincoln National Forest in New Mexico. The two men frequently consulted concerning forestry needs in the Southwest, and Ringland assisted Pinchot in drafting the details of President Roosevelt's famous "midnight proclamations" (1907), which reserved some 100 million acres of additional forest land in the West, including some in Arizona and New Mexico, before, under duress, Roosevelt signed into law a bill prohibiting further forest reserves in six western States except by an act of Congress. [4]

Ringland Appointed

The next year (1908) Pinchot appointed Ringland to be the district forester for District (later Region) 3, which at that time included not only New Mexico and Arizona but portions of Oklahoma and Arkansas as well. With headquarters in Albuquerque, Ringland assembled an outstanding staff of supervisors and rangers to administer the 18,847,414 acres of national forests for all the people in the southwest (table 3). The forest reserves were renamed national forests in 1907. [5]

Table 3. Origin of national forests in the Southwest

| Dates of establishing proclamations and executive orders |

Original and present names |

|---|---|

| ARIZONA | |

Apache-Sitgreaves (other parts are in New Mexico) |

|

| August 17, 1898 | Black Mesa Forest Reserve |

| July 1, 1908 | Part of the Black Mesa Forest Reserve became the Apache National Forest |

Coconino National Forest |

|

| August 17, 1898 | San Francisco Mountains Forest Reserve |

| July 2, 1908 | All of the San Francisco Mountains Forest Reserve and parts of the Black Mesa, Tonto, and Grand Canyon Forest Reserves consolidated as the Coconino National Forest |

Coronado National Forest (the entire forest in Arizona and New Mexico) |

|

| November 5, 1906 | Baboquivari Forest Reserve |

| November 6, 1906 | Huachuca Forest Reserve |

| November 7, 1906 | Tumacacori Forest Reserve |

| July 2, 1908 | Baboquivari, Huachuca, and Tumacacori Forest Reserves consolidated as the Garces National Forest |

| April 11, 1902 | Santa Rita Forest Reserve |

| July 2, 1902 | Santa Catalina Forest Reserve |

| May 25, 1907 | Dragoon National Forest |

| July 2, 1908 | Santa Rita, Santa Catalina, and Dragoon National Forests consolidated as the Coronado National Forest |

| April 17, 1911 | Garces and Coronado National Forests consolidated as the Coronado National Forest |

| July 30, 1902 | Chiricahua Forest Reserve |

| November 5, 1906 | Peloncillo Forest Reserve |

| July 2, 1908 | Chiricahua and Peloncillo Forest Reserves consolidated as the Chiricahua National Forest (portion in New Mexico) |

| July 6, 1917 | Chiricahua and Coronado National Forests consolidated as the Coronado National Forest |

Kaibab National Forest |

|

| February 20, 1893 | Grand Canyon Forest Reserve |

| July 2, 1908 | All of the San Francisco Mountains and parts of the Black Mesa, Tonto, and Grand Canyon Forest Reserves consolidated as the Coconino National Forest |

| June 28, 1910 | Part of the Coconino National Forest together with certain other land not heretofore reserved became the Tusayan National Forest |

| May 22, 1908 | Dixie National Forest (Arizona) |

| July 2, 1908 | Kaibab National Forest |

| March 18, 1924 | Dixie consolidated with the Kaibab National Forest |

| August 4, 1934 | Tusayan and Kaibab National Forests consolidated as Kaibab National Forest |

Prescott National Forest |

|

| May 10, 1898 | Prescott Forest Reserve |

| December 30, 1907 | Verde Forest Reserve |

| July 2, 1908 | Prescott and Verde National Forests consolidated as the Prescott National Forest |

| October 22, 1934 | 249,201 acres transferred from Tusayan to Prescott National Forest |

Sitgreaves National Forest |

|

| July 1, 1908 | Parts of the Black Mesa and Tonto National Forests consolidated as the Sitgreaves National Forest |

Tonto National Forest |

|

| October 3, 1905 | Tonto Forest Reserve |

| October 22, 1934 | Bloody Basin transferred from Prescott to Tonto National Forest (151,285 acres) |

NEW MEXICO |

|

Apache National Forest (other parts are in Arizona) |

|

| January 23, 1925 | A portion of Datil National Forest (originally part of the Magdalena and Gila River Forest Reserves) transferred to Apache National Forest |

Carson National Forest |

|

| November 7, 1906 | Taos Forest Reserve |

| July 1, 1908 | Taos National Forest and part of Jemez National Forest consolidated as the Carson National Forest |

| June 16, 1923 | 63,708 acres in Taos County transferred from Santa Fe National Forest to Carson National Forest |

Cibola National Forest |

|

| October 5, 1906 | Mt Taylor Forest Reserve |

| November 5, 1906 | San Mateo Forest Reserve, Magdalena Forest Reserve |

| November 6, 2906 | Manzano Forest Reserve |

| April 16, 1908 | Mt Taylor National Forest consolidated with Manzano National Forest |

| June 18, 1908 | Datil National Forest |

| July 2, 1908 | San Mateo National Forest added to Magdalena National Forest |

| February 23, 1909 | Magdalena and Dad National Forests consolidated as Datil National Forest |

| March 2, 1909 | Zuni National Forest |

| September 10, 1914 | Zuni National Forest consolidated with Manzano National Forest as Manzano National Forest |

| December 3, 1931 | Name of the Manzano changed to Cibola National Forest and a portion of the Datil transferred to the Cibola |

Gila National Forest |

|

| March 2, 1899 | Gila River Forest Reserve |

| February 6, 1907 | Big Burros Forest Reserve |

| June 18, 1908 | Big Burros consolidated with Gila National Forest |

| December 24, 1931 | Portion of the Datil transferred to the Gila National Forest |

Lincoln National Forest |

|

| July 26, 1902 | Lincoln Forest Reserve |

| November 5, 1906 | Gallinas Forest Reserve |

| April 19, 1907 | Guadalupe National Forest |

| April 24, 1907 | Sacramento National Forest |

| July 2, 1908 | Guadalupe and Sacramento National Forests consolidated as the Alamo National Forest; the Gallinas and Lincoln National Forests consolidated as the Lincoln National Forest |

| June 6, 1917 | Alamo National Forest transferred to Lincoln National Forest (effective July 1) |

Santa Fe National Forest |

|

| January 11, 1892 | Pecos River Forest Reserve |

| October 12, 1905 | Jemez Forest Reserve |

| July 1, 1908 | Pecos River National Forest changed to Pecos National Forest |

| July 1, 1915 | Jemez and Pecos National Forests consolidated as the Santa Fe National Forest |

| October 3, 1905 | Portales Forest Reserve |

| March 1907 | Portales Forest Reserve restored to the public domain |

Source: USDA Forest Service, Division of Engineering, Technical Services Branch, Establishment and Modification of National Forest Boundaries: A Chronological Record, 1891-1959, 92 pp.

It would not be an easy task. Most cattlemen and sheepherders resented any curtailment of their free use of public pasture and doubly resented the fees and restrictions levied by the men of the more efficient Forest Service after 1905. They saw the imposition of fees for grazing in the forest reserves as simply a means "to support a still greater number of 'experts' to travel around the country in Pullman Palace cars—living in opulence and luxury at government expense, while the poor stockman or ranchman is struggling for existence and to make ends meet." [6]

The facts were, of course, quite different. A ranger's salary was only $75 to $90 per month, out of which he had to buy his uniform, support himself, and maintain a string of at least three horses. The gray uniform with riding breeches, boots, campaign hat, and a double-breasted overcoat was (if bought at all) carefully put away for official occasions. The ranger's daily work outfit consisted of sombrero, blue shirt, denim jacket, and work pants—"Levi Strausses" as they were called in contrast to the "choke bores" that the ranchers labeled the tailored riding breeches favored by easterners and British visitors. [7] Only slowly did rangers begin to wear Forest Service uniforms on regular duty. In their personal day-to-day dealing with cattlemen, sheepherders, and loggers, forest rangers preferred not to look too conspicuous. As ranchers came to know the well-qualified and dedicated young rangers, however, public opinion slowly shifted. By the time of World War I (1914), one ranger reported that the people in his area had changed their attitudes from unfriendliness to support and approval of grazing administration and regulation. [8]

The forests, mountains, and plateaus of New Mexico and Arizona in the early 20th century were a horseman's world. A successful ranger had to ride and know how to care for his animals. There were few roads, and most of these were too rough for wagons. The region was too vast for walking, the railroads were several days' distance to the north or south, and there were no automobiles. A good horseman on a good saddle horse was "on top" and in charge of all he surveyed. [9]

|

| Figure 6.—Reconnaissance camp at Three Forks, Kaibab National Forest, 1910. |

Ranger Duties

Ranger duties usually dealt with surveying, grazing leases, timber cutting contracts, fire protection, and inspections. But life was far from dull. Sometimes duties ran from the tragic to the humorous. Two incidents will illustrate the extremes. In 1905 ranger R.L. Neill was helping a local peace officer arrest a Mexican fugitive at Williams. The man suddenly broke away, produced a gun, and began shooting at the officers. Neill drew his own gun and killed the fugitive with one shot. Neill was exonerated. In contrast, ranger Elliot Barker, while on an inspection tour, discovered a pretty 16-year-old girl fishing through the ice, with illegal equipment, out of season, on government property. She could not pay the fine and Barker knew that the judge would not put her in jail, so he continued the case and delayed filing charges on the violation. This called for him to ride out periodically to her father's ranch and within a year Barker married the young woman. As he related, "she has been fishing with me ever since." [10]

|

| Figure 7.—A power line on the Prescott National Forest, about 1910. |

With the coming of Ringland, there began a systematic appointment of qualified young foresters to key positions in the Southwestern Region. The Yale Forestry School, which was endowed by the Pinchot family and was Ringland's alma mater, was the favored source of new recruits, but graduates of Cornell, Michigan, and Carl Schenck's school at Biltmore, NC, were also appointed (figure 8). As early as 1909, Ringland organized a ranger school at the Fort Valley Experiment Station in Arizona. The program was one month long and was so successful that a second session was held. The first session was run by A.O. Waha, the second by Allan S. Peck. Among the instructors of the Fort Valley Ranger School were some foresters who later became prominent in the profession, including Earle H. Clapp, Bernard Recknagel, and J.H. Allison. Unfortunately, the legal officer of the Department of Agriculture at Washington ruled in 1910 that there was no authority to conduct such a school, so the program was terminated after only one year. This ruling was, apparently, part of the 'legalism' of the Taft administration, which held that an activity was illegal unless it was specifically authorized by Congress. This legalism was, no doubt, related to the Ballinger-Pinchot controversy of 1910, which resulted in Pinchot's ouster as Forest Service Chief. [11]

Ringland set a personal example for the foresters in District (Region) 3. Although small of stature and boyish looking, he enforced service regulations and stood up to wealthy ranchers and politicians alike. He regularly wore the foresters' uniform and insisted that his men do likewise, especially at meetings and formal occasions. To keep better informed about conditions in the several forest areas, he insisted on clear, concise reports sent promptly every month. As he knew that many ranchers did not understand the Forest Service goals, mistrusted all Federal employees, and believed the many rumors that were floating about, he regularly sought means to reassure them. In 1909 he persuaded Territorial Governor George Curry to invite Pinchot, who was traveling in the West, to come to Santa Fe and address the legislature. The visit was a complete success. Pinchot's crusading enthusiasm for the conservation cause affected and permeated the audience, and his knowledge, integrity, and sense of fair play impressed his listeners. An excerpt from the Santa Fe New Mexican ?? of March 15, 1909, bespoke his conquest:

Mr. Pinchot, when he arose, before he even spoke a word, created a favorable impression that enlisted the sympathy of his audience. Tall and spare, with eyes deep set and thoughtful, hair sprinkled with gray, aquiline nose and clean cut features that betokened a character of force and yet of kindness, he impressed even the casual student of human nature as a man who was bound to make an impress upon whatever cause he would champion. His very mannerisms, such as rapid twitching of his eyelashes and his peculiar motion of the right hand bringing it down two or three times within a few inches of the table and then finally altogether, whenever he emphasized a point, or warmed up to his subject, helped to strengthen the bond of sympathy and interest with his hearers.

Leading Politicians

Not the least of Ringland's problems involved the leading politicians of the territories: Senators Albert B. Fall and Ralph Cameron. Fall, a notorious anti-conservationist, had a ranch that adjoined the Alamo National Forest (which later became part of the Lincoln National Forest). He objected to the regulation of grazing permits in the national forest in the interest of homesteaders and small ranchers and the limitation of his own grazing privileges. He kept up a constant attack against Ringland and the Forest Service and once introduced a bill into the U.S. Senate that would transfer the administration of the forest reserves and the appointment of personnel to the State of New Mexico, which would pay the costs and collect the revenues. This bill, of course, failed to pass. On other occasions he sought to abolish the Forest Service and even the Department of the Interior. [12]

|

| Figure 8.—Forest ranger inspecting the range, Cibola National Forest, 1922. |

Cameron was a territorial delegate to Congress and then U.S. Senator when Arizona became a State in 1912. just before President Roosevelt declared the Grand Canyon a national monument in 1905, Cameron and his associates filed a series of mining claims along the south rim and down Bright Angel Trail to the bottom of the canyon. The purpose was, of course, not for mining operations but to control the strategic tourist sites as the wonders of the Grand Canyon became known throughout the country and visitors flocked to the region. The Forest Service appointed mining engineer T.T. Swift to head a team to examine Cameron's claims and file a report with the district forester. According to the report, most of the sites showed no valuable minerals at all, and four or five showed only a trace, far less than would justify mining activities. These findings went to Ringland at Albuquerque, who forwarded them and an adverse report to the Forest Service in Washington, which promptly denied Cameron's claims. Cameron was furious but was unable to reverse the decision. Ringland recalled that soon after he met Senator Cameron by chance at a restaurant in Phoenix. The Senator accused Ringland of trying to "ruin him" and smilingly said that he had a notion "to shoot you with a double-barreled shotgun." Although joking about the resort violence, Cameron was dead serious about the rejection his mining claims, and his frustration was apparent. [13]

Timber Inventory

High on the list of projects for the foresters was a systematic inventory of timber stock for the entire region. This directive had come from the Washington headquarters, and Ringland gave it urgency and priority. In a letter of December 1908 to forest supervisors, he stressed "the need to definite data as to the amount and character of timber on the forest of the southwest is imperative [as a basis for a farsighted timber policy]." This was called timber reconnaissance and went on steadily in all of the forests of the region until completed. [14]

It was Ringland's practice to assign new employees to reconnaissance teams to cruise the timber at a given national forest site. In July 1909, Aldo Leopold arrived in Albuquerque fresh from his studies at Yale, where he had earned a master's degree in forestry. His first assignment was to lead a party of six to cruise and map the timber in the Apache National Forest in eastern Arizona. The next year (1910) Yale graduate Raymond E. Marsh also joined the Forest Service and was assigned to the Southwestern Region. He was sent to join Leopold in the Apache National Forest along with other freshmen foresters O.F. Bishop from Yale and R.E. Hopson from Michigan. [15]

The trip was interesting and informative to the three young foresters. They took the Santa Fe train to Holbrook, AZ, where they transferred to a stagecoach (described by Marsh as "something out of the Wild West") bound for Concho. From there they took a lighter one-horse spring wagon to Springerville, arriving the evening of the second day. The ride across the rolling countryside of "magnificent distances" was new and inspiring to Marsh, who had grown up in the East. The next day they boarded a freighter's wagon through the rough country to the reconnaissance camp at the headwaters of the Black River. J. Howard Allison, who had received his master of science from Yale in 1906, was in general charge of timber reconnaissance for the region, and he was on hand to organize and get the Apache party underway. Then he departed for other areas and left the timber cruising team in the hands of Leopold. [16]

As described by Marsh, timber cruising included estimating the volume of timber and describing its character on each 40-acre block. They made sketch maps showing its location, natural features, manmade structures, boundaries, and contours. Each forester carried a Jacob's staff, compass, barometer, and hand counter, as well as his lunch and a canteen. By noting the trees on a sample plot, the forester would estimate the volume of marketable timber on a 40-acre tract. Within the sample he counted the number of 16-foot logs, the number of logs per 1,000 board feet, and the total board feet. A row of three sections or about 2,000 acres constituted two days' work, and the forester learned by experience to make accurate estimates and appraisals. [17]

In 1911 Aldo Leopold moved to the Carson National Forest as deputy forest supervisor and Marsh soon followed as chief of reconnaissance. The headquarters staff, probably with Leopold's leadership, published a monthly paper called the Carson Pine Cone which gave personal news, reports on timber sales and grazing leases, announcements, and on occasion a bit of humor. [18]

Leopold Becomes Supervisor

By March 1912, Leopold became acting supervisor when C.C. Hall left, and before the end of the summer he was formally appointed. Soon afterward, Marsh was promoted to deputy supervisor's desk. The two became a strong team, and the monthly issues of the Pine Cone reflected their accomplishments. Marsh paid tribute to Leopold as a hardworking, hard-driving, able, well-liked chief. [19] Leopold was all of these and more. He was the rare intellectual who was also a skilled outdoorsman, hunter, hiker, and explorer. He was a philosopher who was happiest when he was in the wild back-country. He reveled in his position as forest supervisor, which he considered far and away the best post in the service. [20]

Unfortunately, this association continued only a few months. In April 1913, while trying to settle a range dispute within the national forest, Leopold was caught in a flood and then in a blizzard. He became thoroughly soaked and had to sleep in his wet bedroll. He developed pain and swelling in both knees so severe that he could not ride and could hardly walk. A local doctor diagnosed his illness as rheumatism and prescribed the wrong treatment. Soon his legs were bloated, and he was taken to Santa Fe where a specialist determined that he had acute nephritis. [21]

There followed about 18 months during which Leopold took leave. He spent several months with his family in Iowa and consulted other specialists. Although he retained the title of supervisor, he was unable to return to the Carson National Forest, and Marsh carried on the work and eventually became forest supervisor. In the meantime Leopold read Thoreau, John Burroughs, and other nature writers and began to consider the significance of what he had seen and learned on the Gila River and the upper reaches of the Rio Grande. When he was finally able to return to limited duty in 1915, Ringland brought him to the regional headquarters at Albuquerque and made him acting head of grazing in the office of operations. [22]

Leopold's enforced inactivity gave him time to contemplate the effects of erosion on the fragile, delicately balanced environment of the Southwest, the consequences of the rapidly multiplying deer herds, and the long-range results of the continuing war on predators. Like most young foresters, he had equated a flourishing deer herd with control or even extermination of wolves, mountain lions, and coyotes. He recalled a cruising expedition (probably in 1910 or 1911 in the Apache National Forest) during which he and his companions saw a she-wolf swim across a river and join her cubs on the near side. At once the foresters seized their rifles and pumped lead into the pack until the old wolf was down and the cubs dispersed into the mountain canyons. What happened next was instructive and important to his developing thought.

We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes. I realized then, and have known ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes something known only to her and to the mountain. I was young then, and full of trigger-itch; I thought that because fewer wolves meant more deer, that no wolves would mean hunters' paradise. But after seeing the green fire die, I sensed that neither the wolf nor the mountain agreed with such a view.

Leopold slowly came to the conclusion that while the deer lived in fear of wolves, the mountain lived in fear of its deer, which, when uncontrolled and allowed to multiply without restraints, could destroy a range that might not recover for decades or even centuries. [23]

Too Many Deer

The problem of too many deer was well-illustrated by their spectacular increase in the Kaibab National Forest, north of the Grand Canyon (at this time the Kaibab was not part of the Southwestern Region). There the deer herd rose from 4,000 in 1906 to more than 30,000 by 1924 (later estimates placed the 1924 total at nearer 100,000). Everything was overgrazed, and thousands of deer died of starvation during the winter, including most of the young fawns. [24]

The concept of "thinking like a mountain" intrigued Leopold. The short-range solution would frequently prove disastrous in the long run. Given the fragile balance of the southwestern ecology, Leopold began to realize that decisions made by his generation would greatly affect the options available to the population of the 21st century. He gradually reversed his opinion of wolves and mountain lions. These played their part and were essential to the balance of the southwestern habitat. Control of predators was a reasonable function of conservation, but not campaigns of extirpation. Besides, his great-grandchildren a century hence should not be deprived of seeing these animals.

Wilderness Ideas

It was only a step from the idea of preserving the game of the region to the concept of preserving a portion of a national forest as a permanent wilderness. A large area should be left in its wild state, with no paved roads nor human habitations. As early as 1913, Leopold had broached this idea to Elliot Barker and in 1920 made a similar proposal in an article for the Journal of Forestry. In 1922, Assistant Regional Forester Leopold, now largely recovered from his near-fatal illness, made an inspection trip to the Gila River headwaters country, near where he had begun his forestry career 13 years before. On his return he proposed to set aside some 500,000 acres of the area to become an official wilderness, without roads and only minimum trails. [25] As one of his colleagues described it:

A region which contains no permanent inhabitants, possesses no means of mechanical conveyance, and is sufficiently spacious that a person may spend at least a week or two of travel without crossing his own tracks. [26]

Over the opposition of some of his fellow foresters, Leopold persuaded Frank Pooler, then regional forester of the Southwestern Region, to approve the plan. When officially announced in 1924, the Gila Wilderness was the first area formally designated as such and served as a precedent for the creation of other wilderness areas in the West. [27]

Leopold's work to protect the game and preserve the environment had not been easy. Officials in Washington had repeatedly urged him to accept a transfer to an editorial position at the service headquarters, but he refused, preferring to remain in the desert Southwest where he felt he could make a real contribution. Finally, in 1924, Chief Forester Henry S. Graves ordered him to accept the transfer. Leopold responded with a long letter to his friend Ringland, saying that he did not know if he had "twenty days or twenty years" ahead of him but he wanted to accomplish something definite and not end up in a dead end. If he had to choose between a safe job or pursuing his goals, he would leave the Forest Service. Ringland knew his friend and intervened with the Chief. The orders were changed, and Leopold remained in Albuquerque. [28]

Later in 1924, after the Gila Wilderness was established, Leopold accepted a new assignment as associate director of the U.S. Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, WI. Two years later Ray Marsh, then assistant district forester, also left the region. He would eventually rise to assistant chief of the Forest Service. Ringland had departed in 1916 to serve in World War I and carve out a distinguished career in other branches of government. These three, Ringland, Leopold, and Marsh, strongly influenced policies of the region as they related to grazing, fire protection, timber management, and recreation. Of these many uses, grazing dominated the time and attention of foresters in the early years of the Southwest. [29]

Reference Notes

1. Edwin A. Tucker and George Fitzpatrick, Men Who Matched the Mountains: The Forest Service in the Southwest (Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service, 1972), pp. 1-12.

2. For more on Gifford Pinchot, see his book Breaking New Ground (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1947); Harold T. Pinkett, Gifford Pinchot: Private and Public Forester (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1970); Harold K. Steen, The U.S. Forest Service: A History (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1976).

3. Steen, U.S. Forest Service, p. 75; Pinchot, Breaking New Ground, pp. 261-262. Pinchot actually wrote the letter for Secretary Wilson's signature.

4. Steen, U.S. Forest Service, p. 84; Pinchot, Breaking New Ground, pp. 252-254.

5. "Ringland, Arthur C. (1882-1981)," Journal of Forestry (January 1982). Note: The acreage indicated was achieved by 1920, with minor consolidations and changes between 1908 and 1919.

6. Edwin A. Tucker, "The Forest Service in the Southwest," unpublished manuscript, pp. 126-127.

8. R.R. Hill, "Grazing Administration of the National Forests in Arizona," American Forestry 19 (September 1913)-578-585.

9. Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac (New York: Oxford University Press, 1966), pp. 130-137.

10. Tucker, "The Forest Service in the Southwest," p. 128; Elliott Speer Barker, Beatty's Cabin (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, Fitzpatrick, Men Who Matched the Mountains, pp. 37-38.

11. Arthur C. Ringland and Fern Ingersoll, "Pioneering in Southwest Forestry," Forest History 17 (April 1973): 411.

14. Raymond E. Marsh, "Timber Cruising on National Forests of the Southwest," Forest History 10:3 (October 1969).

15. Susan L. Flader, Thinking Like a Mountain: Aldo Leopold and the Evolution of an Ecological Attitude Toward Deer, Wolves, and Forests (Columbia: "Timber Cruising," pp. 22-23.

16. Marsh, "Timber Cruising," pp. 22-23; Allison later became a professor of forestry at the University of Minnesota.

17. Ibid., pp. 24-26; Tucker and Fitzpatrick, Men Who Matched the Mountains, pp. 116-120.

18. The Carson Pine Cone (January 1912), p. 5. At this time Pinchot was no longer Chief of the Forest Service, but he enjoyed the humor as much as anyone.

19. Tucker, "The Forest Service in the Southwest," vol. 3, p. 1368; Carson Pine Cone (March-December 1912); Marsh, "Timber Cruising," p. 28.

20. See Leopold, A Sand County Almanac, especially "The Land Ethic," pp. 237-264; Flader, Thinking Like a Mountain, p. 9.

21. Flader, Thinking Like a Mountain, pp. 9-10; Tucker and Fitzpatrick, Men Who Matched the Mountains, pp. 38-40.

22. Flader, Thinking Like a Mountain, pp. 9-10; Tucker, "The Forest Service in the Southwest," vol. 3, pp. 1341-1343.

23. Leopold, A Sand County Almanac, pp. 137-141.

24. Flader, Thinking Like a Mountain, pp. 84, 175-176.

25. Dennis Roth, "The National Forests and the Campaign for Wilderness Legislation," Journal of Forest History 28:3 (July 1984):112-125; Leopold, A Sand County Almanac, pp. 265-295.

26. Roderick Nash, "The Strenuous Life of Bob Marshall," Forest History 10 (October 1966):19-23.

27. Roth, "The National Forests and the Campaign for Wilderness Legislation," pp. 112-125; Roderick Nash, Wilderness and the American Mind (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973), pp. 187-199.

28. Flader, Thinking Like a Mountain, p. 13.

29. Ibid., p. 16; Douglas H. Strong, The Conservationists (Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley Press, 1971), pp. 139-154.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

region3/history/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 22-Feb-2008