|

Men Who Matched the Mountains: The Forest Service in the Southwest |

|

CHAPTER XVII

The National Forests of Arizona

|

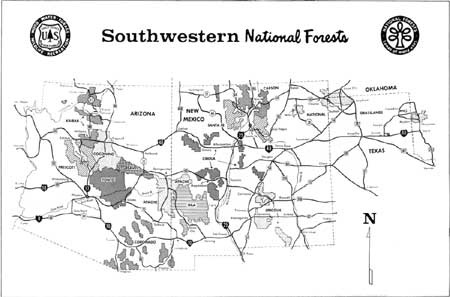

| Southwestern National Forests. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Apache National Forest

John D. Guthrie had been Supervisor of the Apache Forest for only a short time back in 1909 when he and A. O. Waha made an inspection trip of the Forest. They were in Hog Canyon south of Fort Apache when night caught up with them, and they came upon the camp of a young cowboy. They had no equipment for overnight camping, so they asked the cowboy if they could stay with him.

"I didn't have anything but a tent," Benton Rogers, the cowboy, recalled nearly 60 years later. "I told them O.K., that I could stand it if they could. I had a blanket on back of the saddle. I told 'em I'd give 'a part of my bed, and we'd make it all right.'"

They stayed over night and shared breakfast with the cowboy. Before they left, Guthrie asked the cowboy how he liked his work. He told them he didn't like his present job too well.

"What do you think of the Forest Service?" Guthrie asked him.

"Never heard of it," the cowboy replied.

Guthrie explained and told him to write a letter applying for a position in the Forest Service and to be in Springerville a month later.

Benton Rogers did go to Springerville and he got a job as fire guard on the White Mountain Indian Reservation. That was the beginning of more than 30 years with the Forest Service, most of it as a Ranger on the Apache National Forest.

Back in those days most of Benton Rogers' work besides fighting fires was grazing permits. As the demand for lumber from a growing population expanded, the Apache National Forest began to supply that need.

Today, the pine, spruce and fir forests of the Apache are capable of providing an annual cut of 69,000,000 board feet of lumber on a sustained yield basis. The Apache also supplies pulpwood to the Southwest Forest Industries' paper mill at Snowflake. Seventy thousand cords per year are under contract for the next dozen years.

Timber is only one of the important resources of the Apache. This Forest encompasses some of the highest water-producing land in the state of Arizona—and the Forest is managed to produce the maximum possible amounts of usable water. A research project has been underway on Burro Mountain where different cutting practices are tried to determine their effect on water yield and on reestablishment of trees. Watershed erosion projects were also undertaken.

The Apache National Forest is host annually to more than 15,000 hunters and as many as 250,000 fishermen. Improved highways have made the Forest easily accessible and 10 times as many visitors are entering the Forest today as did 15 years ago. (The total for 1971 was more than 659,000 visitor days.) By 1973, it is estimated that the total of recreation visits will reach nearly a million, and the Apache crews are hard put to keep up with demands for recreation facilities.

The original industry—grazing—is still important, and more than 26,000 cattle and horses and 7,300 sheep graze under paid permit on the forest.

Part of the Apache National Forest extends into New Mexico, covering 616,160 acres in Catron County, to make the total acreage of the Apache 1,807,925 acres.

Coconino National Forest

One of the sharpest memories Fred Croxen has of his early years in the Forest Service was that 64-inch snow during the winter of 1915-16 at Flagstaff. It snowed for three days then cleared for a week and got down to 25 degrees below zero.

Today on the Coconino, snow is an important resource. Though they may not appreciate 25 degrees below zero, the winter sports people and the ranchers certainly appreciate those heavy snows that fall on the Coconino. The nationally-famous Arizona Snow Bowl attracts thousands of skiers and the facilities are heavily used throughout the winter.

Like the Apache, the Coconino provides an important annual harvest of timber on its nearly 2,000,000 acres. Logging and mill operations have been a key factor in the economy of Flagstaff since before the turn of the century. Allowable timber cutting on a sustained yield basis is nearly 60,000,000 board feet. Actual timber cut has sometimes exceeded that figure and—depending upon demand—often fallen as low as 30,000,000 board feet. More than 10,000 sheep and 19,000 cattle and horses graze on the Forest under permit. The sale of logs and pulpwood and fees from grazing and special use bring in more than $300,000 a year—one fourth of which is returned to Coconino, Yavapai and Gila Counties. And those special uses are varied and numerous—about a thousand special use permits in all, including such a myriad of uses as public schools, transmission lines, radio and television transmitters, observatories, rifle ranges, cemeteries, water developments, roads and highways, city parks.

Since 1957, the Forest Service has been operating the Beaver Creek pilot test watershed project, covering more than a quarter-million acres in the Coconino Forest. The project is developing information on how to and how much it costs to effectively manage a watershed. The project includes juniper removal, grass seeding, pine thinning and pruning, water measuring, and the relationship of watershed management to livestock grazing, wildlife management and to timber production.

Recreation knows no season on the Coconino, and nearly a million visitors each year enjoy camping, riding, hunting and fishing, skiing, and hiking.

Hiking is a popular recreation on the Coconino today, but Paul Roberts, reminiscing about his early days on the Coconino, recalled a time when hiking was just pure misery.

In 1912 he was with a horseback reconnaissance party, and one of the members of the party was Jim Sizer, an oldtime cowboy and wagon boss, who later became a Supervisor of the Apache National Forest (1922-25).

"I remember our first camp was out at Dead Man's tanks," Roberts related. "Coming back, we were so heavily loaded that Sizer and I were walking. I don't think Sizer had ever walked that far in his life. We got to the top. It was a fairly warm day, and old Jim sat down and leaned against a tree. He had on a pair of heavy boots. He looked down at his boots, and he groaned, 'By God, I'm about caught up on this walkin'.' And he sure was.

Coronado National Forest

The Coronado National Forest is made up of a number of the old Forest Reserves, including the "sneeze-cough group": the Baboquivari, the Huachuca, the Tumacacori. The other consolidations were the Dragoon National Forest and the Santa Rita and Santa Catalina Forest Reserves.

As a result of all these inclusions under one name, the Coronado is a group of "islands" in the desert of southeastern Arizona and about 70,000 acres extending over into Hidalgo County, New Mexico. Lumped together they make a very sizeable 1,800,000-acre Forest.

When Gilbert Sykes started on the Catalina District as a fire lookout in 1919, the only access to the Catalinas was by the old Sabino Trail.

"Everything was packed up on a string of burros by the Maggie Pack Train," Sykes said. "All the supplies, all the furniture, everything up the mountains by pack train. There were some cabins up there then, not many. Groceries, everything went up by pack train. They charged 2-1/2 cents a pound for packing things up.

"There really weren't any recreational facilities, no improved campground. Three or four years later they started a little layout just above Soldier Camp . . . called it a campground. They finally piped water down from Bear Wallow and that was the first recreational area laid out in the mountains."

Today with improved roads and a variety of recreational facilities available in the Santa Catalina Mountains, the Forest provides a popular playground for Tucson and visitors to southern Arizona. Other recreation developments have been undertaken in the Chiricahua Mountains, Madera Canyon in the Santa Rita Mountains, and various developments in the Graham Mountains. At the entrance to Sabino Canyon, fifteen miles from downtown Tucson, a new visitor center was built in 1963 to provide information for the more than one million annual visitors to the Coronado Forest. A self-guided nature trail showing plants in a desert watercourse was dedicated in Sabino Canyon. Explanatory signs and turnouts on the Hitchcock Highway which leads to Mt. Lemmon interpret the Forest terrain and geological formations.

Though outdoor recreation is the Coronado's fastest growing business, it is concerned with watershed rehabilitation, development of improved hunting and fishing, development of forage resources. Timber harvesting is confined to salvage of overmature, dead and dying trees since timber-growing sites on the Coronado are limited and in demand for recreation sites.

Where once there were only horseback or game trails, today there are more than 1400 miles of road system in the Coronado National Forest and about a thousand miles of trails. And where once Gilbert Sykes helped to build a single telephone line and where he used a heliograph to signal other Rangers, there are now 50 permits for radio and television electronic sites, and a hundred and forty miles of telephone and telegraph lines.

Prescott National Forest

J. R. Williams, whose syndicated cartoon "Out Our Way" was so popular in other years, operated the K4 Ranch on Walnut Creek during the 1930's. Jesse Fears, Ranger in charge of the Walnut Creek District, was a good friend of the cartoonist, and they often visited together. Williams used the Prescott National Forest as the locale for many of his cartoons, featuring cowboys and Forest Rangers.

The Prescott National Forest is rich in history, for it surrounds the town of Prescott, which was the first Territorial Capital of Arizona. Within and adjacent to the Forest are locations of old army outposts. There are shafts and tunnels all over the Forest, dating from the years of the mining booms that started when gold was discovered on Lynx Creek in 1863. Where once there were busy mining communities, today only a prospector or two remains.

The settlement of Prescott began during the Civil War when gold was discovered, and the need for sluice boxes was met by the miners who whipsawed logs into lumber. In 1865 a portable sawmill was set up just south of the present city of Prescott to use logs from the Forest. The Forest continued to supply wood in many forms for the mining industry throughout the territorial days of Arizona. The Prescott National Forest is still supplying the wood needs of mining and a variety of other industries, including utility poles and railroad ties. Two sawmills operate yearlong.

Because of the growing importance of recreation in the Forest, the Rangers are pretty choosey about where logs can be cut, even to selecting individual trees for cutting so as to preserve scenic values and to protect recreation sites. More than 600,000 visitor days in the Prescott Forest are tallied each year, and it is estimated that in the 70's this will be a million visits. The Prescott is particularly popular with residents of the Salt River Valley seeking relief from the heat during the summer in the cool million-and-a-quarter acres of Forest.

This part of Arizona has always been an important ranching area, and today the Prescott has grazing allotments supporting 15,400 cattle and horses. Sheep driveways cross the Forest from winter to high summer ranges, and 28,000 sheep use the driveways.

The Prescott National Forest has had some bad fires—some of which were started by people and could have been prevented! In 1955, the Johnson fire burned 19,000 acres near Crown King, and the next year the Mingus Mountain fire burned 14,000 acres. The Battle fire in 1972 burned over 28,000 acres south of Prescott. The Prescott has air tankers, based at Prescott Airport, which are used to cool down a fire or prevent it from spreading. The tankers use a mixture of fire retarding chemicals and water to drop on fire areas.

Watershed management is an important part of Prescott Forest work since the Forest has few "live" or yearlong streams. Watersheds that have eroded are being rehabilitated and two small areas are under continuing study as part of watershed management research.

Kaibab National Forest

The deer herd of the North Kaibab Division of the Kaibab National Forest has been famous since before the turn of the century. This was one of the favorite hunting areas of Teddy Roosevelt, and it is the favorite hunting ground of nearly six thousand hunters annually—more than half of whom get their deer.

In years gone by the deer herd had so multiplied that it was necessary to reduce the deer population by thousands upon thousands, for the herd had reached the point where many thousands were dying off from lack of forage. Today, as with the other forest resources, the deer herd is controlled scientifically to maintain a balance between numbers and the forage supply.

Timber harvesting is big business on the North Kaibab. Large scale operations began in 1942 and increased to 42 million board feet allowable cut.

Kaibab is an Indian word for "lying-down mountain." Indians believed that the high plateau north of the Grand Canyon was a mountain lying on its side.

The Kaibab National Forest is split into four sections. One surrounds the town of Williams, the second along the south side of Grand Canyon, and the third division, the North Kaibab, and the fourth a small isolated Forest area north of the Colorado River, west of the North Kaibab Division.

Recreation visits to the Kaibab have been increasing rapidly in the past few years and it has been estimated that the present 900,000 visitor days will reach a million by 1972 when there will be a total of 8 campgrounds.

The famous deer herd of the North Kaibab has overshadowed the deer herds south of the Grand Canyon, but there is also good hunting on the South Kaibab and the number of hunters has doubled in the past 10 years.

Arthur J. "Crawford" Riggs, of Santa Fe, spent five years as a Ranger on the North Kaibab beginning in 1937, and he recalls that when he first went there range conditions were just starting to come back after the big die-off and reduction of the deer herd. "You could still see the old deer line in the brush and trees, about four to six feet high," Riggs said. "I was there five years and when I left you could hardly see the deer line, which shows how fast, how quickly, the country can recuperate, when you reduce your grazing animals."

Scientific management of the available forage for wildlife and domestic animals has been a continuing process. During the eight-year period from 1954 to 1962, range technicians analyzed over 1,000,000 acres of Kaibab range land, and a management plan for more efficient use of 900,000 acres was developed with stockmen. This includes a rest-rotation stagger system so that forage is not subjected to grazing on all allotments during the growing season. Twelve thousand cattle and horses and 10,000 sheep are grazed on 58 allotments. The Forest Service works with the Arizona Game and Fish Department as well as with grazing permittees in order to keep deer breeding herds and cattle numbers in balance with the existing forage conditions.

Special use permits on the Forest include more than 100 public service facilities such as an airport, cemetery, reservoir, school, waterline, playground, resort and privately operated ski area near Williams.

Sitgreaves National Forest

Timber is big business on the Sitgreaves National Forest. The allowable annual cut of logs on a sustained yield basis is 56.2 million board feet.

The establishment of a pulpmill at Snowflake, on the edge of the Forest, was an important stimulant to the economy of Arizona and intensive forest management. The demand for pulpwood makes it economically feasible to thin out the young, dense, overcrowded stands of trees. This practice makes it possible to furnish pulpwood for the mill and speeds up the growth of the remaining crop trees.

Five timber operators, employing hundreds of men, and production of a variety of forest products make timber the most important business in the Sitgreaves area.

This area of eastern Arizona is still ranching country, too, but today with only 4,100 cattle and less than 15,000 sheep on Forest permits, the business is considerably smaller than in those days of overgrazing before the turn of the century and before the establishment of the National Forests. The old-time Sitgreaves Supervisor Paul Roberts recalled that one outfit once unloaded "28,000 cattle in one fell swoop in the spring of 1885, and that was enough to overstock a lot of range before they got them distributed around."

Today the 800,000-acre Forest range is supervised on a scientific range management basis to provide for proper stocking and maximum sustained forage production.

Timber management, too, is on a more scientific basis than in the past. Watershed rehabilitation, tree planting, grass seeding, arroyo stabilization, and erosion control all enter into timber management. This is a far cry from the days nearly 50 years ago when Supervisor Roberts had to depend on ex-cowboys to mark trees preliminary to a sale. His files reveal complaints to the Regional Office that he did not have a single technical forester on the Sitgreaves.

"When I look back and think of the technical advancements over the years, why you know it's just a doggone wonder that we did as well as we did in those early years," Roberts reminisced. "We know so much more now than we did then, technically, there's no comparison. I hear a lot of old timers say, 'Well, these young fellows—they don't do as good a job as we did,' and a lot of that kind of stuff. As a matter of fact they're probably doing ten times better job than we ever did. Because they've got much more basic information and are much better trained, technically, before they ever get out of the schools. They can't help but do a much better job. So I think they ought to be given credit for it."

In Paul Roberts' day, the Sitgreaves Supervisor and Rangers weren't much concerned with recreations visits, but today recreation is an important part of the job. Annual visits have increased tremendously to nearly 300,000, and it is anticipated this figure will be about 450,000 by 1972. Campgrounds and picnic sites, water systems, parking areas, sanitation facilities have been installed to take care of the growing demand. Fishing and hunting are attractions, too, and Forest personnel works closely with the Arizona Game and Fish Department in improving wildlife habitat to provide another annual crop for harvest.

Tonto National Forest

Back in 1935 when F. Lee Kirby was in his first year as Supervisor of the Tonto National Forest, he received an application for a strange request. N. B. F. "Uncle Mac" McCord, a retired railroader, asked for about an eighth of an acre within the Forest for his final resting place.

Uncle Mac had already picked out the place—a high, lonesome spot on a granite knoll on the slope of Screwtail Hill, 45 miles from Phoenix. "I don't want no damned lawn mowers running over my grave," Uncle Mac had told friends.

Supervisor Kirby had been in the Forest Service as fire guard and Ranger for more than 20 years and had a lot of experience dealing with the rugged individuals who had helped Arizona to grow into a great State. He honored the request.

Uncle Mac wrote to thank him, saying: "After I locate there, I will not violate any of the regulations that are enumerated in the Permit. Thank you, it won't be long now."

Today a modern highway passes 100 yards from the lonely grave, and there for all to see is the crude inscription chiseled on a giant boulder: MACK'S REST.

That's probably the strangest special use permit that has been issued in the Tonto Forest, where about 900 special permits are in effect. The others cover such things as more than 300 miles of power lines, nearly 400 miles of roads, 28 radio and electronic sites, many miles of telephone line, a number of apiaries, and even a seismological station.

Because of its location a short distance from Phoenix, the Tonto is a favorite recreation area for residents and visitors to the Valley of the Sun. Recreation visits have jumped from half a million in 1955 to more than two million annually, with an estimate of 3,750,000 by 1973. As a result, planners are working on a $4 million program of recreation development during the present decade. Camps, picnic grounds (for a million picnickers), boat launching ramps, swimming beaches, and other recreation sites have been built. Visitor information programs have been launched and vista sites established.

The Tonto does not have as much timber available as other forests, but timber cutting is the main industry of the town of Payson and total annual cut has been as high as 18-1/2 million board feed. Pulpwood harvesting has also been possible to help supply the needs of the pulpwood mill at Snowflake.

In watershed management, the Tonto has an important role. There are six reservoirs of the Salt and Verde River drainages: Saguaro, Canyon, Apache, Roosevelt, Horseshoe and Bartlett Lakes, and the goal is to manage the watersheds to provide the maximum possible silt-free water for these reservoirs. The reservoirs do triple duty in providing year-long irrigation, domestic water, and water recreation in the desert.

This is still ranch country, and the largest number of livestock on any Forest in the Southwest—more than 42,000 cattle and horses and 11,268 sheep and goats are grazed on the Tonto— the largest of the National Forests in Arizona, with 2,886,185 acres.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

tucker-fitzpatrick/chap17.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2008